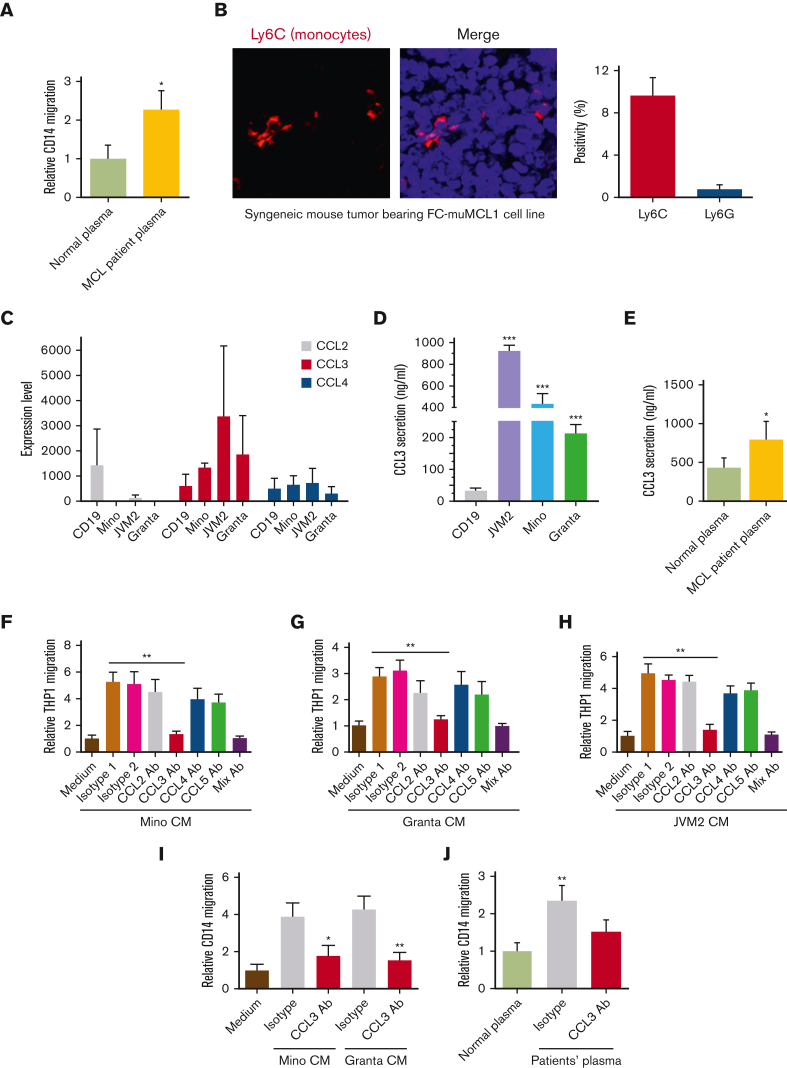

Figure 1.

Role of tumor-CCL3 in monocyte migration. (A) CD14+ Mo was incubated with normal plasma (n = 3) or plasma of patients with MCL (n = 5) and migration was assessed using chemotaxis assay (∗P < .05). (B) Immunofluorescent staining was performed on the syngeneic mouse tumor–bearing FC-muMCL1 murine MCL cell line using the Ly6C (red) antibody. Data were repeated in 3 mouse tumors, and representative data are shown along with quantification. (C) RNA sequencing data demonstrating chemokines (CCL2, CCL3, and CCL4) expression in the MCL cell lines (n = 3) and normal CD19+ B-cells (n = 2). (D) The secretion level of CCL3 in normal CD19+ B cells and MCL cell lines were measured by ELISA. ∗∗∗P < .001 vs CD19. (E) CCL3 was measured in the plasma collected from patients with MCL (n = 5) and normal control participants (n = 3) by ELISA. (F-H) CM collected from MCL cell lines (Mino, Granta, and JVM2) were used to attract THP1-Mo using a chemotaxis assay. An isotype control or 0.5 μg/mL neutralizing anti-CCL2, anti-CCL3, anti-CCL4, or anti-CCL5 antibodies was included in the assay. The data presented are representative of 3 independent experiments. ∗∗P < .01 vs media alone. (I-J) Mino or Granta CM (I) or plasma of patients with MCL (J) (n = 5) was used to attracting CD14+ Mo in the chemotaxis assay. The data presented are representative of 3 independent experiments. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01.