Abstract

Improving lipophilicity for drugs to penetrate the lipid membrane and decreasing bacterial and fungal coinfections for patients with cancer pose challenges in the drug development process. Here, a series of new N-alkylated-2-(substituted phenyl)-1H-benzimidazole derivatives were synthesized and characterized by 1H and 13C NMR, FTIR, and HRMS spectrum analyses to address these difficulties. All the compounds were evaluated for their antiproliferative, antibacterial, and antifungal activities. Results indicated that compound 2g exhibited the best antiproliferative activity against the MDA-MB-231 cell line and also displayed significant inhibition at minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) values of 8, 4, and 4 μg mL–1 against Streptococcus faecalis, Staphylococcus aureus, and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus compared with amikacin. The antifungal data of compounds 1b, 1c, 2e, and 2g revealed their moderate activities toward Candida albicans and Aspergillus niger, with MIC values of 64 μg mL–1 for both strains. Finally, the molecular docking study found that 2g interacted with crucial amino acids in the binding site of complex dihydrofolate reductase with nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate.

Introduction

Cancer is a terminology that refers to a group of chronic noncommunicable diseases relating to the uncontrolled growth of abnormal cells and their invasion and metastasis to adjacent tissues, causing adverse changes in physiological conditions resulting in the disorder of the vital organs in the human body.1−4 According to the American Cancer Society, cancer is still the second leading cause of human mortality worldwide, with 19.3 million new cases causing nearly 10 million deaths in 2020.5,6 By 2040, these figures are estimated to be about 29.5 million newly diagnosed cases and 16.4 million deaths.2 Breast cancer is the most common malignancy and the second most fatal cancer in women.7 Triple-negative breast cancers (TNBCs) are a group of tumors defined by a lack of estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER-2) expression.8 Poor prognosis and treatment resistance are prominent obstacles and considerable problems for disease control. Hence, constant efforts are given to meet the requirements of the search for new classes of anticancer drugs.

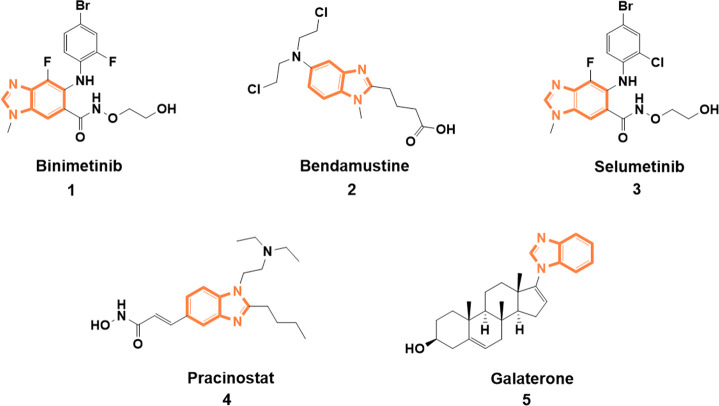

In recent years, various benzimidazole-derived anticancer drugs have been discovered, leading to attention in drug development due to their diverse biological activity and therapeutic application. Benzimidazole is well-known as a crucial N-heterocyclic core with a unique structure and safety profile. With a purine-like feature and a part of vitamin B12 derivative, benzimidazole possesses a privileged substructure so that it can easily interact with biopolymers to form a compatibility system for the action of biologically active compounds.9,10 It is also a commonly employed five-membered N-heterocycle among the approved drugs of the US Food and Drug Administration (2015–June 2020).11 Examples of benzimidazole-based molecules with clinical approval are binimetinib (1), bendamustine (2), selumetinib (3), pracinostat (4), and galaterone (5)12 (Figure 1). Given the information above, benzimidazole and its derivatives have become an excellent scaffold for developing anticancer drugs.

Figure 1.

Benzimidazole-based clinically approved anticancer drugs.

In addition, the considerable increase in drug resistance in microorganisms such as Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, and Candida albicans caused by overuse and nosocomial infections threatens to reverse medical advances over the past 50 years.13 All these challenges drive the discovery and development of new classes of potent compounds for use as antimicrobials. In the last 2 decades, the research on benzimidazole-containing antimicrobial drugs has gained the attention of many scientific groups. Ersan et al. reported that 2-(benzyl/phenylethyl/phenoxymethyl) benzimidazole derivatives showed promising antimicrobial effects against Gram-positive bacteria and fungi but relatively low effects against Gram-negative bacteria.14 N-Substituted benzimidazoles 6(15) and 7(16) (Figure 2) effectively inhibited the growth of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus MRSA ATCC4330 and USA 300, respectively, exhibiting minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) values up to 4 μg mL–1, and chemical substance 7 was identified to be bactericidal. Woolley (1944) published the first report on the antimycotic effect of an azole molecule, which is a fortuitous discovery that announced for the first time the fungicidal activity of the benzimidazole moiety.17 Chlormidazole (8)18 and nocodazole (9)19 (Figure 2), examples of benzimidazole-based antifungal drugs, are clinically used. Chlormidazole was introduced as the first marketed topical antifungal medication.20 Accordingly, it served as a pioneer for extensive investigations into the antifungal properties of benzimidazole compounds. Furthermore, benzimidazole-containing compounds are a broad-spectrum antiparasitic agent recommended by the World Health Organization for clinical use in human and veterinary medicine.21,22 For example, albendazole and mebendazole are mainly prescribed for treating intestinal helminth parasites such as nematodes, trematodes, and tapeworm.s23,24

Figure 2.

Benzimidazole derivatives (6–9) as antimicrobial agents.

According to published pharmacological documents, the biological properties of the benzimidazole system were strongly influenced by substitution at N-1 and C-2 positions; in particular, position N-1 can positively influence chemotherapeutic efficacy.25,26 In brief, the idea for designing target compounds in the present study was based on three structural aspects resembling the information mentioned above: (a) planarity of the benzimidazole nucleus, (b) substitution on the aromatic ring at position 2, and (c) aliphatic chains with different lengths at the N-1 position.

Dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR or EC 1.5.1.3) is an enzyme involving the biosynthesis of tetrahydrofolate (THF) to promote the synthesis of purines and some amino acids, especially thymidine.27 DHFR is responsible for maintaining the THF pools in cells. Given that DHFR is the only source of THF, it acts as the Achilles’s heel of proliferating cells.28 Hence, this enzyme is an excellent example of a potential target for antibacterial substances. On the basis of the information above, molecular docking studies were performed between the DHFR from Staphylococcus aureus (PDB ID: 3FYV) and the most potent antibacterial compound on S. aureus and MRSA. The results were compared with the interactions of the inhibitor iclaprim (XCF) and the standard drug amikacin.

In general, the primary goal of the drug discovery race is to seek more active molecules with multiple effects, including antiproliferative, antibacterial, and antifungal activities. The rise in the invention of these drugs is advantageous for patients with cancer who are most at risk for superinfection due to their weakened immune systems. With a broad spectrum of activity, benzimidazole should be a starting material for this study. Herein, N-alkylated 2-(substituted phenyl)-1H-benzimidazole derivatives with different substituents at N-1 and C-2 positions were designed and synthesized to evaluate their antiproliferative and antimicrobial activities.

Result and Discussion

Chemistry

Three 2-(substituted phenyl)-1H-benzimidazole derivatives (1–3) were synthesized following the reported procedure illustrated in Scheme 1 by a condensation reaction between o-phenylenediamine and aromatic aldehyde derivatives under mild conditions. The yields after the purification step ranged from 53 to 82% (Table 1). The synthetic pathway of 21 title compounds (1a–g, 2a–g, and 3a–g) is depicted in Scheme 2. These compounds were prepared from the synthesized 2-phenyl benzimidazole derivatives (1–3) and dimethyl carbonate (DMC) or alkyl bromide bearing long-chain hydrocarbon in the presence of sodium carbonate with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) as solvent. As shown in Scheme 2, the reaction conditions were slightly modified depending on the properties of alkylating agents. In the N-methylation of aromatic NH-containing heterocyclic compounds, the reactions were heated up to 140 °C under atmospheric pressure due to the nature of DMC acting as a methylation agent at a relatively high temperature.29 When using ethyl bromide, the reaction mixture was placed in an ice bath to curb the evaporation of a reagent, whereas the other reactions with C3–C7 bromide were conducted at room temperature.30

Scheme 1. Synthesis of 2-(Substituted phenyl)-1H-benzimidazole (1–33).

Table 1. Yield and Reaction Time of Benzimidazole Derivatives (1a–g, 2a–g, and 3a–g).

| no. | cpd. | R | R1 | yield (%) | RT (h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1a | H | CH3 | 83 | 12 |

| 2 | 1b | H | C2H5 | 50 | 5.0 |

| 3 | 1c | H | n-C3H7 | 91 | 1.7 |

| 4 | 1d | H | n-C4H9 | 84 | 3.0 |

| 5 | 1e | H | n-C5H11 | 80 | 3.9 |

| 6 | 1f | H | n-C6H13 | 77 | 4.8 |

| 7 | 1g | H | n-C7H15 | 65 | 5.3 |

| 8 | 2a | 4′-OCH3 | CH3 | 84 | 48 |

| 9 | 2b | 4′-OCH3 | C2H5 | 96 | 3.3 |

| 10 | 2c | 4′-OCH3 | n-C3H7 | 95 | 1.3 |

| 11 | 2d | 4′-OCH3 | n-C4H9 | 72 | 4.0 |

| 12 | 2e | 4′-OCH3 | n-C5H11 | 71 | 4.3 |

| 13 | 2f | 4′-OCH3 | n-C6H13 | 98 | 3.9 |

| 14 | 2g | 4′-OCH3 | n-C7H15 | 90 | 3.4 |

| 15 | 3a | 2′-CF3 | CH3 | 72 | 4.0 |

| 16 | 3b | 2′-CF3 | C2H5 | 84 | 1.7 |

| 17 | 3c | 2′-CF3 | n-C3H7 | 98 | 0.7 |

| 18 | 3d | 2′-CF3 | n-C4H9 | 92 | 3.0 |

| 19 | 3e | 2′-CF3 | n-C5H11 | 97 | 0.7 |

| 20 | 3f | 2′-CF3 | n-C6H13 | 69 | 1.0 |

| 21 | 3g | 2′-CF3 | n-C7H15 | 89 | 0.7 |

Scheme 2. Synthesis of N-Alkylated-2-(substituted phenyl)-1H-benzimidazole (1a–g, 2a–g, and 3a–g).

(i) Dimethyl carbonate, reflux in 140 °C. (ii) Ethyl bromide in an ice bath. (iii) C3-C7 bromide, room temperature.

The FTIR, NMR, and HRMS spectral data of the synthesized compounds concurred with the hypothesized structural molecules. The FTIR spectra for compounds 1–3 showed stretching vibrations for the N–H group at 3452, 3384, and 3431 cm–1, respectively. In the 1H NMR spectra, the N–H proton appeared as a singlet in the downfield region of δ 12.73–12.90 ppm. The N-alkylated compounds 1a–f, 2a–f, and 3a–f showed the disappearance of N–H stretching of the 1H-benzimidazole derivatives (1–3) of the previous step and the presence of typical patterns for sp3 C–H stretch at frequencies less than 3000 cm–1 (2992–2838 cm–1). The FTIR spectra for alkylated benzimidazole derivatives (i.e., 1a–g, 2a–g, and 3a–g) indicated stretching absorption peaks at 3067–3002, 1670–1608, and 1591–1522 cm–1 attributed to sp2 C–H, C=N, and C=C, respectively. The two strong bands at approximately 1259–1250 and 1032–1029 cm–1 for 2a–g were assigned to C–O stretching in methoxyl substitution, and 3a–g displayed the characteristic C–F vibration at about 1183–1171 cm–1 corresponding to the trifluoromethyl group. In accordance with the 1H NMR spectrum of compounds 1a–3a, the N–CH3 protons were detected at around 3.56–3.88 ppm as a singlet signal, and the N–CH2 methylene protons of compounds 1b–g, 2b–g, and 3b–g on the N–CH2(CH2)nCH3 substituent (0 ≤ n ≤ 5) appeared as a triplet at 3.96–4.31 ppm, whereas the other aliphatic protons on the alkyl chain were found at approximately 0.70–1.68 ppm. Moreover, the protons of a methoxy substituent in position 4′ of the 2-phenyl ring provided a singlet signal at 3.84–3.85 ppm in the 1H NMR spectrum of 2a–g. The aromatic protons of all target compounds were observed in the downfield region at 7.12–7.98 ppm. In the 13C NMR spectra, the peaks around 10–46 ppm were assigned to carbon atoms of the alkyl chain in compounds 1a–g, 2a–g, and 3a–g. In addition, the aromatic carbons displayed signals in the δ 110–161 ppm range. The carbon CF3 in 3a–g was determined at 120–127 ppm as a quartet peak with J = 272 Hz. Further, 2a–g showed signals at approximately 55 ppm, which were attributed to carbon atoms of the methoxy group. Finally, the HRMS analysis of all target compounds showed a pseudo molecular ion peak [M + H] + in agreement with the proposed molecular formula weight and revealed the formulation of these compounds.

Antiproliferative Activity

In this study, all compounds were tested for antiproliferative activity by using the SRB method with camptothecin as a positive control against MDA-MB-231 (a human breast cancer cell line). The results are summarized in Table 2. The compounds were synthesized on the basis of the differences in functional groups on the 2-phenyl ring and alkyl-chain length on the N-1 position to clarify their influences over antiproliferative activity on the MDA-MB-231 cell line.

Table 2. Antiproliferative (IC50, μM) Activity of Synthesized Compounds 1–3, 1a–g, 2a–g, and 3a–g.

| IC50 ± SD (μM) | ||

|---|---|---|

| no. | cpd. | MDA-MB-231 |

| 1 | 1 | >100 |

| 2 | 2 | >100 |

| 3 | 3 | >100 |

| 4 | 1a | >100 |

| 5 | 1b | >100 |

| 6 | 1c | 61.31 ± 6.69 |

| 7 | 1d | 49.57 ± 2.88 |

| 8 | 1e | 21.93 ± 2.24 |

| 9 | 1f | 26.50 ± 2.40 |

| 10 | 1g | 33.10 ± 2.10 |

| 11 | 2a | >100 |

| 12 | 2b | 76.05 ± 6.68 |

| 13 | 2c | 85.23 ± 5.60 |

| 14 | 2d | 29.39 ± 0.71 |

| 15 | 2e | 72.10 ± 3.48 |

| 16 | 2f | 62.30 ± 4.12 |

| 17 | 2g | 16.38 ± 0.98 |

| 18 | 3a | 55.11 ± 2.79 |

| 19 | 3b | 83.67 ± 3.10 |

| 20 | 3c | 53.76 ± 3.75 |

| 21 | 3d | 40.83 ± 4.34 |

| 22 | 3e | 45.12 ± 4.64 |

| 23 | 3f | 64.50 ± 2.42 |

| 24 | 3g | 39.07 ± 2.72 |

| 25 | camptothecin | 0.41 ± 0.04 |

As shown in Table 2, three of the 1H-benzimidazole derivatives (1–3) were found to be less active toward the MDA-MB-231 cell line (IC50 > 100 μM). A notable detail is that the N-substitution with straight-chain alkyl groups provided almost better antiproliferative activity (IC50 = 16.38–100 μM) than the unsubstituted ones. Compounds 1a–g (phenyl at position 2 of the benzimidazole ring) possessing substituents with alkyl chains from one carbon to seven carbons, respectively, exhibited a linear increase in anticancer effects from 100 to 21.93 μM, corresponding to 1a to 1e, and then a slight decrease to 33.10 μM at 1g. For the p-methoxy substituted analog (2a–g), 2g (heptyl group attached to N-1) was the most effective one with an IC50 value of 16.38 μM followed by 2d (butyl group attached to N-1) with an IC50 value of 29.39 μM. The other compounds showed moderate activity in the order of 2f > 2e > 2b > 2c > 2a, with an IC50 value range of 62.30–100 μM. Similarly, in terms of inhibitory effects against MDA-MB-231, 3g possessing a heptyl group was found to be the most active (IC50 = 39.07 μM) in the series of 3a–g. Meanwhile, 3d possessing a butyl group showed an IC50 value of 40.83 μM, whereas the other compounds in the series (IC50 = 45.12–83.67 μM) showed less significant activity in descending sequence of 3e, 3c, 3a, 3f, and 3b. In the structure–activity relationship examination of all three series, compounds 1e, 2g, and 3g with hydrophobic moiety, including pentyl and heptyl substitutions, were found to be the most effective anticancer molecules, wherein the p-methoxy substituent at the 2-phenyl ring revealed a positive effect, resulting in the best antiproliferative activity of 2g. Many studies have reported that the strong lipophilic nature of molecules plays a vital role in biological activity due to their correlation with membrane permeation related to the capacity of transmembrane diffusion and drug disposition.31,32 Thus, as noted above, the cytotoxic enhancement of 1e, 2g, and 3g could be attributed to their lipophilicity and substitution on the phenyl ring.

Furthermore, the accepted mechanism of action for the anticancer activity of synthesized compounds is summarized in Figure 3. These compounds suppress the overgrowth of a cancer cell via the cell cycle arrest at phases S,33 G0/G1,34 or G2/M,35 causing aberrant DNA replication, chromatin condensation, and abnormal mitosis resulting in apoptosis.36 In addition, many previous reports discovered that benzimidazoles instigate apoptosis by disturbing mitochondrial membrane potential, resulting in the release of proapoptotic factor (e.g., cytochrome c) into the cytosol to initiate caspase activation, which induces the death of cancer cells.37−39

Figure 3.

Illustration of the antiproliferative mechanism of action of synthesized compounds.

In Vitro Antibacterial and Antifungal Activities

Antifungal Activity

Compounds 1–3, 1a–g, 2a–g, and 3a–g were tested for antifungal activities against Candida albicans ATCC 10231 and Aspergillus niger ATCC 16404 by using amikacin as a standard drug. The results indicated that most compounds exhibited weak-to-moderate bioactivities against fungal strains (Table 3). Compound 1, having no substituents on the 2-phenyl ring and N-1 position, was inactive with two tested strains. By contrast, compounds 1a–d exerted stronger antifungal potency with MIC values ranging from 64 to 512 μg mL–1, which implied that introduction of alkyl groups at the 1-position of 2-phenyl-1H-benzo[d]imidazole led to positive antifungal activities. Meanwhile, compound 2 with the 4-OCH3 group on the phenyl ring showed promising inhibition against both tested strains, with MIC values in the range of 128–512 μg mL–1. Compound 3 with the −CF3 group on the C-2 position of phenyl moiety also displayed inhibitory potency against A. niger (MIC = 521 μg mL–1) but weak activity against C. albicans (MIC >1024 μg mL–1). In the series of 2a–g, compounds 2c, 2e, and 2f endowed with moderate activities against C. albicans and A. niger (MIC = 64–128 μg mL–1) illustrated improved antifungal activities over their precursor (MIC = 128–512 μg mL–1). Furthermore, N-alkylated 2-(2-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-1H-benzo[d]imidazole derivatives (3a–g) demonstrated that increasing the number of carbon atoms (over one carbon) in a linear chain at the N-1 position influenced the antifungal potency negatively. Compound 3a had better antifungal activities against C. albicans (MIC = 256 μg mL–1) and A. niger (MIC = 64 mg mL–1) than its precursor 3, which had MIC values of >1024 μg mL–1 (C. albicans) and 512 μg mL–1 (A. niger). However, the replacement of the methoxy group and a hydrogen atom on the phenyl moiety with trifluoromethyl and the presence of a longer alkyl chain having carbon atoms from two to seven (compounds 3b–g) resulted in a loss of action against the two tested strains with MIC values of more than 1024 μg mL–1, which is similar to the previous report of Khabnadideh et al.4 These findings suggested that the character of the substituents simultaneously determines antifungal activities at the second position and the length of the carbon atoms in the alkyl chain at the first position. In accordance with a previous review, a plausible antifungal mode of action for the synthesized compounds is illustrated in Figure 4 by inhibition of the ergosterol synthesis causing fungal cell membrane degradation.40,41 After crossing the cell membrane, these molecules have previously been reported to be able to inhibit the cytochrome P450 enzyme lanosterol 14α-demethylase (CYP51),19,42−44 a crucial enzyme that plays an essential role in sterol biosynthesis, especially ergosterol.45 These molecules reduce the function of 14α-demethylase by interacting with heme iron in the active site and then inducing the enzyme to alter its active site geometry and block the demethylation of lanosterol to ergosterol, one of the fungal membrane’s structural components regulating membrane fluidity and permeability.41,46,47 When ergosterol production is inhibited, the fungal cell wall destabilizes and swiftly disrupts, resulting in the death of the fungus.48,49

Table 3. In Vitro Antibacterial and Antifungal Activities of Compounds 1–3, 1a–g, 2a–g, and 3a–g as MIC Values (μg mL–1)a.

| Antibacterial

activity (MIC, μg mL–1) |

Antifungal activity (MIC, μg mL–1) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gram-positive |

Gram-negative |

||||||

| cpd. | EC | PA | SF | SA | MRSA | CA | AN |

| 1 | – | –– | – | – | – | – | – |

| 2 | – | – | – | – | – | 512 | 128 |

| 3 | – | – | – | – | – | >1024 | 512 |

| 1a | 256 | – | 512 | 256 | 256 | 256 | 256 |

| 1b | 256 | – | 512 | 256 | 256 | 64 | 64 |

| 1c | >1024 | – | 512 | 256 | 256 | 64 | 64 |

| 1d | >1024 | – | >1024 | 256 | 256 | 512 | 512 |

| 1e | >1024 | – | 256 | 64 | 64 | >1024 | >1024 |

| 1f | >1024 | – | 128 | 64 | 64 | 1024 | 512 |

| 1g | >1024 | – | 128 | 64 | 64 | >1024 | >1024 |

| 2a | 256 | – | >1024 | 512 | 512 | >1024 | 64 |

| 2b | 1024 | – | 1024 | 512 | 512 | >1024 | 64 |

| 2c | >1024 | – | >1024 | 512 | 512 | 128 | 128 |

| 2d | >1024 | – | >1024 | 512 | 512 | >1024 | >1024 |

| 2e | >1024 | – | >1024 | 256 | 256 | 64 | 64 |

| 2f | >1024 | – | 512 | 64 | 64 | >1024 | >1024 |

| 2g | 64 | – | 8 | 4 | 4 | 64 | 64 |

| 3a | 512 | – | >1024 | 512 | 512 | 256 | 64 |

| 3b | >1024 | – | >1024 | 512 | 512 | >1024 | >1024 |

| 3c | >1024 | – | >1024 | 512 | 512 | >1024 | >1024 |

| 3d | >1024 | – | >1024 | 512 | 512 | >1024 | >1024 |

| 3e | >1024 | – | >1024 | 128 | 128 | >1024 | >1024 |

| 3f | >1024 | – | >1024 | 1024 | 1024 | – | – |

| 3g | >1024 | – | >1024 | >1024 | >1024 | – | – |

| Amikacin | 2 | – | 256 | 4 | 8 | – | – |

| Ketoconazole | – | – | – | – | – | 8 | 8 |

EC: Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922); PA: Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC 27853); SF: Streptococcus faecalis (ATCC 29212); SA: Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 29213); MRSA: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 43300); CA: Candida albicans (ATCC 10231); AN: Aspergillus niger (ATCC 16404).

Figure 4.

Antifungal mode of action of synthesized compounds.

Antibacterial Activity

In vitro antibacterial activities of all newly synthesized compounds were examined with two strains of Gram-negative bacteria, namely, E. coli ATCC 25922 and Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853, and three strains of Gram-positive bacteria, namely, Streptococcus faecalis ATCC 29212, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213, and MRSA ATCC 43300. Table 3 presents the values of MIC of compounds. Because of the poor qualitative activity by the disk diffusion test of all 1H-benzimidazole derivatives (1–3), none were further tested for MIC. Moreover, strain P. aeruginosa was not susceptible to a series of N-alkylated 1H-benzimidazole (1a−g, 2a−g, and 3a−g), similar to the results of Evrard et al. (2021).50 Compounds 1a–b, 2a–b, 2g, and 3a showed weak-to-moderate activity against Gram-negative bacteria (E. coli), with MIC values ranging from 64 to 1024 μg mL–1. The findings revealed that these 1-alkyl-2-(substituted phenyl) benzimidazole derivatives may be ineffective at inhibiting the growth of Gram-negative bacteria.51,52 Moreover, all 1-alkyl-2-phenyl-1H-benzo[d]imidazole derivatives (1a–g) exhibited good inhibition against three Gram-positive bacteria with MIC values of 64–512 μg mL–1, except for compound 1d carrying the n-butyl group, which showed no intrinsic antibacterial activity against S. faecalis, with an MIC greater than 1024 μg mL–1. Regarding the S. faecalis activity (as shown in Table 3), compound 1f with the hexyl group and compound 1g with the heptyl group were found to be twice as effective as the control amikacin (MIC = 256 μg mL–1), with an MIC value of 128 μg mL–1. In the series of N-alkylated 2-(4-methoxyphenyl)-1H-benzo[d]imidazole derivatives (2a–g), compound 2g (4-methoxyphenyl and N-heptyl) (Figure 5) was identified as a remarkable antibacterial agent against S. faecalis with an MIC value of 8 μg mL–1, which is 25-fold lower than that of amikacin (MIC = 256 μg mL–1). Besides, it exerted promising growth inhibition against S. aureus and MRSA, with MIC values of 4 μg mL–1, compared with amikacin (MIC = 4 and 8 μg mL–1, respectively).

Figure 5.

Minimum inhibitory concentration of compound 2g against four strains of bacteria (E. coli, E; S. faecalis, S; S. aureus, SA; resistant-methicillin Staphylococcus aureus, MRSA).

In a previous study, 1,2-disubstituted 1H-benzimidazole derivatives with n-propyl and n-hexyl groups displayed their potency to inhibit MRSA (N315), with MIC values ranging from 41 to 8 μg mL-1.53,54 Noor ul Huda and co-workers54 synthesized six 3,3′-(1,3-phenylene (methylene)(1-alkyl-benzimidazolium) salts with a long chain at the N-1 position (butyl, propyl, benzyl, isopropyl, ethyl, and heptyl) and screened them for their antibacterial efficacy. Among the six derivatives, the compound bearing the heptyl group displayed the best zone of inhibition (21.00 mm against S. aureus and 21.60 mm against MRSA10 and MRSA11) due to its longest straight chain, which facilitated enhanced absorption into the cells. Thus, longer alkyl substitution could cause a positive effect on bacterial growth suppression. Meanwhile, the presence of the trifluoromethyl group on the 2-phenyl ring and an increase in the length of alkyl substitution (3a–g) were responsible for reducing antibacterial activity. For example, 3g, which contained the heptyl group, showed a loss of activity against S. aureus and MRSA, whereas 3a–f demonstrated moderate activity against S. aureus and MRSA (MIC = 128–1024 μg mL–1) but weak activity against S. faecalis (MIC > 1024 μg mL–1). These data indicated that the synthesized benzimidazole derivatives carry more potent antibacterial activities against Gram-positive bacteria and MRSA than against Gram-negative bacteria, which have been proven by many previous studies worldwide.51,55,56 This finding may be attributed to the difference in the structures of the cell membranes of Gram-positive and -negative bacteria. Gram-negative organisms are well-known to be troublesome. Although they have a relatively thin peptidoglycan cell wall (<10 nm), the outer layer is composed of other components (lipopolysaccharides, phospholipids, and periplasmic space) that act as a defensive coat in particular response to antibacterial agents.57 Meanwhile, Gram-positive bacteria possess only a peptidoglycan membrane without any extra protection layer, which makes them more susceptible to attacks and easy to have broken important bonds in the structure.58 Gram-negative bacteria endorsed a higher hydrophilic characteristic for cell penetration due to a passage through a porin, whereas Gram-positive bacteria prefer a higher lipophilic character due to transmembrane passage.59 Thus, as mentioned above, the designed compounds showed the corresponding structure to antibacterial ability.

Molecular Docking Studies

In accordance with the antibacterial data, the most active compound 2g was selected for docking to DHFR-NADPH from S. aureus co-crystallized with XCF (PDB ID: 3FYV). In an attempt to gain insights into the mode of action, the docking study was conducted in the binding site of DHFR-NADPH to determine the probable interactions at the enzymatic level. The docking results, including docking score (kJ mol–1) and binding mode of amino acids inside the active site of DHFR-NADPH with interacting groups of the ligands in compounds (XCF, amikacin, and 2g), are tabulated in Table 4 and presented in Figure 6. After the binding site was established, the reference ligand XCF was removed and redocked into the binding site, and this process resulted in a root mean square deviation (RMSD) = 0.8157 Å (<2 Å, Figure 6A). Its docking score was −27.77 kJ mol–1; it interacted with amino acids Hoh233, Asp27, Phe92, and Leu5 by hydrogen bonds, especially Leu28, Val31, Ile50, and Leu54, to form a hydrophobic pocket, leading to antibacterial action against S. aureus and MRSA (Figure 6B).

Table 4. Docking Scores of XCF, 2g, and Amikacin against S. aureus Strainsa.

| MIC (μg mL–1) |

residues interacted by |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cpd. | S. aureus | MRSA | docking score (kJ mol–1) | hydrogen bond | hydrophobic interaction |

| XCF | 0.0360 | 260 | –27.77 | Hoh233, Asp27, Phe92, Leu5 | Leu28, Val31, Ile50, Leu54, Leu20, and Phe92 |

| 2g | 4 | 4 | –17.36 | Ala7 | Leu28, Val31, Ile50, Leu54, Leu20, Phe92, Val6, Ser49, Ala7, and Glan19 |

| amikacin | 4 | 8 | –6.83 | Asn18, Asp27, Ala7, Leu5, and Ser49 | Val31, Ile50, Gln19, Ser49, Asn18, Val6, Leu5, Ile14, Phe98, Phe92, and Leu20 |

The underlined symbols denote the amino acid quartet.

Figure 6.

2D and 3D interaction models of XCF (A and B), 2g (C and D), and amikacin (E and F) with the binding site of the DHFR–NADPH complex. NADPH is shown in green and DHFR in cyan ribbons, the hydrogen bonds are shown as dash lines, and the green curve lines illustrate the hydrophobic interactions.

Meanwhile, the most promising compound (2g) and amikacin were docked to the same binding site as XCF (Figure 6C/D and 6E/F), and they exhibited docking scores of −17.36 and −6.83 kJ mol–1, respectively, as evidence of quick fitting into the DHFR-NADPH binding site. Although amikacin formed a tertiary structure with the DHFR-NADPH complex through hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions, amikacin possessed the hydrophobic pocket with a lack of crucial amino acids Leu28 and Leu54. Meanwhile, 2g constructed the binary DHFR protein-2g complex through amino acid Ala7 by hydrogen bond, and it conserved the important residues Leu28, Val31, Ile50, and Leu54 in its hydrophobic ones. As a result, compound 2g obtained a docking score of −17.36 kJ mol–1, better than amikacin with −6.83 kJ mol–1. These phenomena proposed that amikacin and 2g can inhibit S. aureus similarly, but 2g demonstrated better inhibition against MRSA. However, 2g and amikacin lack hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions with the other amino acids in the binding site of the complex, which is present in binding site of XCF, such as Hoh233 and Phe92, following worse docking scores of 2g and amikacin (Table 4). Thus, the inhibitory activity of S. aureus strains of 2g and amikacin was lower than that of XCF.27 These results showed that compound 2g could exert antibacterial activities with considerable potency to S. aureus and MRSA via the DHFR-NADPH inhibitor mechanism and become a promising future candidate for antibacterial treatment. These correlations between experimental results and molecular docking studies are valuable for refining the structural properties and enhancing the activities.

Conclusions

In conclusion, three 2-(substituted phenyl)-1H-benzimidazole and 21 N-alkylated-2-(substituted phenyl)-1H-benzimidazole derivatives, including four new compounds (3b, 3d, 3f, and 3g), were synthesized, and their structural characterization was confirmed by FTIR, 1H and 13C NMR, and HRMS. Pharmacological studies were carried out to evaluate the influences of substituents in positions 1 and 2 on the biological activities. The antiproliferative test against a human breast cancer cell line (MDA-MB-231) revealed that introducing the alkyl group in position 1 supported the activity. Further, the antimicrobial results against five bacteria and two fungi indicated that most compounds showed moderate-to-excellent inhibitory activities in inhibitory activities toward fungi and Gram-positive bacteria due to the hydrophobic nature of the alkyl group. Compound 2g emerged as a multitargeted molecule among all synthesized compounds due to its most effective antiproliferative, antifungal, and antibacterial activities, especially its better inhibitory action against S. faecalis, S. aureus, and MRSA than amikacin. The molecular docking study of 2g revealed that the antibacterial activities are due to the ability to form important hydrophobic interactions in the binding site of DHFR-NADPH.

Experimental Section

Materials and Instruments

All general chemicals were purchased from Acros Organics (Belgium), Merck (Germany), Sigma-Aldrich (USA), Guangdong Guanghua (China), and Chemsol (Vietnam) and used without further purification unless otherwise stated.

Thin-layer chromatography was conducted on silica gel 60 F254, and the spots were located under UV light (254 nm). The uncorrected melting points were conducted in open capillaries on a Krüss Optronic M5000 melting point meter (Germany). The UV–vis spectra were recorded on a UV–vis Metash UV-5100 spectrophotometer or JASCO V-630 UV–vis spectrophotometer. The NMR spectra were measured using either a Bruker Advanced 500 or 600 MHz NMR spectrometer in (CD3)2SO. The chemical shifts (δ) were expressed in ppm and referred to the residual peak of tetramethylsilane as an internal standard. The IR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Tensor 27 FTIR spectrometer or PerkinElmer Frontier FTIR spectrometer by using KBr pellets. The high-resolution mass spectra were measured on the Agilent 6200 series TOF and 6500 series Q-TOF LC/MS system. The purity of all tested compounds was >95% according to HPLC performed on the Shimadzu SPD-20A HPLC system (Shimadzu, Japan) equipped with a BDS Hypersil C18 column (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm) or the Agilent 1290 Infinity equipped with a Zorbax Eclipse Plus C18 column (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm).

Synthesis

General Procedure for the Synthesis of 2-(Substituted phenyl)-1H-benzimidazole

The synthesis of compounds (1–3) was described in our previous report,61 and the characteristics are listed below.

2-Phenyl-1H-benzo[d]imidazole (1)

A yellowish powder, yield: 53%. mp 294.5–295.5 °C. UV–vis (λmax, MeCN/nm): 241, 301. FTIR (KBr, cm–1): 3452, 3047, 1620, 1409, 1274. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz): δ = 12.90 (s, 1 H), 8.19–8.17 (m, 2 H), 7.65 (s, 1 H), 7.54–7.56 (m, 3 H), 7.49 (tt, J = 2.2 Hz, 7.2 Hz, 1 H), 7.21 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 2 H) ppm. 13C{1H} NMR (DMSO-d6, 125 MHz): δ = 151.2, 143.8, 135.0, 130.1, 129.8, 128.9, 126.4, 122.5, 121.6, 118.8, 111.2 ppm. HRMS (ESI): m/z calculated for C13H10N2 + H+ [M + H+]: 195.0922. Found 195.0949.

2-(4-Methoxyphenyl)-1H-benzo[d]imidazole (2)

A yellowish powder; yield: 82%. mp 224.5–225.5 °C. UV–vis (λmax, MeCN/nm): 248, 306, 320. FTIR (KBr, cm–1): 3384, 3056, 1609, 1505, 1254, 1181. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 8.12 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2 H), 7.56 (s, 2 H), 7.16–7.18 (m, 2 H), 7.11 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2 H), 3.84 (s, 3 H) ppm. 13C{1H} NMR (DMSO-d6, 125 MHz): δ = 161.4, 150.6, 137.0, 130.7, 128.6, 127.5, 123.0, 120.2, 114.6, 114.4, 55.5 ppm. HRMS (ESI): m/z calculated for C14H12N2O + H+ [M + H+]: 225.1028. Found 225.1039.

2-(2-(Trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-1H-benzo[d]imidazole (3)

A yellowish powder, yield: 82%. mp 273.5–274.5 °C. UV–vis (λmax, MeCN/nm): 238, 283. FTIR (KBr, cm–1): 3431, 3047, 1650, 1543, 1312, 1121. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 12.74 (1 H, s), 7.95 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1 H), 7.84 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.80 (quint, J = 8.0 Hz, 2 H), 7.69 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.54 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.21–7.27 (m, 2H) ppm. 13C{1H} NMR (DMSO-d6, 125 MHz): δ = 149.3, 143.4, 134.4, 132.3, 132.1, 130.2, 130.1, 127.9, 127.7, 126.9, 126.54126.5, 126.5, 124.8, 122.6, 122.6, 121.5, 119.1, 111.4 ppm. HRMS (ESI): m/z calculated for C14H9F3N2 + H+ [M + H+]: 263.0797. Found 263.0792.

General Procedure for the Synthesis of Compound 1a, 2a, 3a

The mixture of 1–3 (0.1 mmol) and dimethyl carbonate (0.3 mmol) in 5 mL DMSO was refluxed in the presence of potassium carbonate at 140 °C. After the reaction (as evident from TLC), the reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature and poured into distilled water. The resulting solution was stirred for 15 min until the oil layer appeared and then extracted with n-hexane and diethyl ether (3:2, v/v). The organic layer was concentrated under reduced pressure to obtain the raw product. The purification was performed by recrystallization from an adequate solvent.

1-Methyl-2-phenyl-1H-benzo[d]imidazole (1a)

A dark yellow solid, yield: 83%. mp 91.7–92.3 °C. UV–vis (λmax, MeCN/nm): 236, 264, 288. FTIR (KBr, cm–1): 3057, 2923–2852, 1573–1523, 1327. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 7.84–7.86 (m, 2 H), 7.68 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.62 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1 H), 7.55–7.60 (m, 3 H), 7.30 (td, J = 1.0 Hz, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.25 (td, J = 1.3 Hz, J = 7.6 Hz, 1 H), 3.88 (s, 3 H) ppm. 13C{1H} NMR (DMSO-d6, 125 MHz): δ = 153.0, 142.4, 136.6, 130.1, 129.6, 129.2, 128.6, 122.3, 121.9, 118.9, 110.5, 31.6 ppm. HRMS (ESI): m/z calculated for C14H12N2 + H+ [M + H+]: 209.1073. Found 209.1077.

2-(4-Methoxyphenyl)-1-methyl-1H-benzo[d]imidazole (2a)

A white solid, yield: 84%. mp 111.7–112.3 °C. UV–vis (λmax, MeCN/nm): 244, 293. FTIR (KBr, cm–1): 3047, 2923–2851, 1663–1536, 1251, 1023. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 7.80 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2 H), 7.65 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 1 H), 7.58 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1 H), 7.27 (td, J = 1.3 Hz, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.22 (td, J = 1.5 Hz, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.12 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 2 H), 3.86 (s, 3 H), 3.85 (s, 3 H) ppm. 13C{1H} NMR (DMSO-d6, 125 MHz): δ = 160.3, 153.0142.5, 136.5, 130.7, 122.4, 122.0, 121.7, 118.7, 114.1, 110.3, 55.3, 31.60 ppm. HRMS (ESI): m/z calculated for C15H14N2O + H+ [M + H+]: 239.1179. Found 239.1186.

1-Methyl-2-(2-(trifluoromethyl) phenyl)-1H-benzo[d]Imidazole (3a)

A yellow solid, yield: 72%. mp 86.7–86.3 °C. UV–vis (λmax, MeCN/nm): 276, 283. FTIR (KBr, cm–1): 3082, 2949–2866, 1681–1532, 1386, 1183. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 7.98 (m, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.87 (m, 1 H), 7.83 (m, 1 H), 7.68–7.72 (m, 2 H), 7.62 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1 H), 7.33 (td, J = 1.3 Hz, J = 7.9 Hz, 1 H), 7.27–7.29 (m, 1 H), 3.56 (s, 3 H) ppm. 13C{1H} NMR (DMSO-d6, 125 MHz): δ = 150.23, 142.38, 135.38, 132.52, 132.31, 130.72, 129.08, 128.82, 128.80, 128.83, 128.59, 128.35, 126.92, 126.67, 126.64, 126.60, 126.56, 124.74, 122.57, 120.39, 122.65, 121.98, 119.24, 110.53 30.57 ppm. HRMS (ESI): m/z calculated for C15H11F3N2 + H+ [M + H+]: 277.0947. Found 277.0958.

General Procedure for the Synthesis of Compounds 1b, 2b, and 3b

Compounds 1b–3b (0.1 mmol) in 5 mL DMSO were stirred in an ice bath for 15 min in the presence of potassium carbonate. Subsequently, ethyl bromide (0.3 mmol) was added quickly to the reaction mixture. After the reaction was completed (as evident from TLC), the reaction mixture was poured into distilled water. The resulting solution was stirred for 15 min until the oil layer appeared and then extracted with n-hexane. Then, the organic layer was concentrated under reduced pressure to obtain the raw product. The purification was performed by recrystallization from an adequate solvent.

1-Ethyl-2-phenyl-1H-benzo[d]imidazole (1b)

A white crystal, yield: 50%. mp 83.7–84.3 °C. UV–vis (λmax, MeCN/nm): 236, 287. FTIR (KBr, cm–1): 3053, 2989–2894, 1692–1610, 1251–1267. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 7.76 (m, 2 H), 7.68 (dd, J = 1.0 Hz, J = 8.0 Hz, 2 H), 7.64 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.56–7.61 (m, 3 H), 7.29 (td, J = 1.3 Hz, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.24 (td, J = 1.3 Hz, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 4.31 (q, J = 7.5 Hz, 2 H), 1.33 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 3 H) ppm. 13C{1H} NMR (DMSO-d6, 125 MHz): δ = 152.6, 142.7, 130.4, 129.6, 129.0, 128.7, 122.3, 121.9, 119.1, 110.6, 39.1, 14.9 ppm. HRMS (ESI): m/z calculated for C15H14N2 + H+ [M + H+]: 223.1230. Found 223.1233.

1-Ethyl-2-(4-methoxyphenyl)-1H-benzo[d]imidazole (2b)

A transparent crystal, yield: 96%; mp 98.7–99.3 °C. UV–vis (λmax, MeCN/nm): 244, 291. FTIR (KBr, cm–1): 3049–3008, 2985–2839, 1610–1531, 1247, 1028. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 7.70–7.72 (m, 2 H), 7.65 (dd, J = 1.0 Hz, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.61 (dd, J = 1.0 Hz, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.25–7.27 (m, 1 H), 7.22–7.25 (m, 1 H), ), 7.12–7.14 (m, 2 H), 4.30 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2 H), 3.85 (s, 3 H), 1.33 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 3 H) ppm. 13C{1H} NMR (DMSO-d6, 125 MHz): δ = 160.2, 152.6, 142.7, 135.3, 130.4, 122.6, 122.0, 121.7, 118.9, 114.2, 110.5, 55.3, 39.1, 14.9 ppm. HRMS (ESI): m/z calculated for C16H16N2O + H+ [M + H+]: 253.1335. Found 253.1341.

1-Ethyl-2-(2-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-1H-benzo[d]imidazole (3b)

A white solid, yield: 84%; mp 97.7–98.3 °C. UV–vis (λmax, MeCN/nm): 256, 276, 283. FTIR (KBr, cm–1): 3061, 2992–2875, 1663–1583, 1314, 1171. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 7.98 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1 H), 7.87 (td, J = 0.6 Hz, J = 7.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.83 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1 H), 7.73 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1 H), 7.70 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.67 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1 H), 7.32 (td, J = 1.2 Hz, J = 7.2 Hz, 1 H), 7.26 (td, J = 1.2 Hz, J = 7.2 Hz, 1 H), 4.03 (quint, J = 7.2 Hz, 2 H), 1.17 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3 H) ppm. 13C{1H} NMR (DMSO-d6, 150 MHz): δ = 149.60, 142.59, 134.12, 132.48, 132.12, 130.70, 128.98, 128.90, 128.89, 128.77, 128.57, 128.37, 126.76, 126.73, 126.70, 126.67, 125.33, 124.52, 122.70, 122.60, 121.87, 120.89, 119.39, 110.71, 38.76, 14.46 ppm. HRMS (ESI): m/z calculated for C16H13F3N2 + H+ [M + H+]: 291.1110. Found 291.1119.

General Procedure for the Synthesis of Compound 1c–g, 2c–g, 3c–g

The mixture of 1–3 (0.1 mmol) and alkyl bromide (c–g) (0.3 mmol) in 5 mL DMSO was refluxed in the presence of potassium carbonate at ambient temperature. After the reaction was completed (as evident from TLC), the reaction mixture was poured into distilled water. The resulting solution was stirred for 15 min until the oil layer appeared and then extracted with n-hexane. Then, the organic layer was concentrated under reduced pressure to obtain the raw product. The purification was performed by recrystallization from an adequate solvent.

2-Phenyl-1-propyl-1H-benzo[d]imidazole (1c)

Sticky yellowish oil, yield: 91%. UV–vis (λmax, MeCN/nm): 239, 265, 285. FTIR (KBr, cm–1): 3059, 2965–2876, 1647–1523, 1282–1249. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 7.75–7.78 (m, 2 H), 7.68 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.64 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.55–7.60 (m, 3 H), 7.28 (td, J = 1.2 Hz, J = 7.3 Hz, 1 H), 7.24 (td, J = 1.2 Hz, J = 7.3 Hz, 1 H), 4.26 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 2 H), 1.68 (sextet, J = 7.5 Hz, 2 H), 0.72 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 3 H) ppm. 13C{1H} NMR (DMSO-d6, 125 MHz): δ = 153.0, 142.6, 135.6, 130.6, 129.6, 129.1, 128.7, 122.3, 121.8, 119.1, 110.8, 45.5, 22.5, 10.8 ppm. HRMS (ESI): m/z calculated for C16H16N2 + H+ [M + H+]: 237.1386. Found 237.1392.

1-Butyl-2-phenyl-1H-benzo[d]imidazole (1d)

Dark yellow oil, yield: 84%. UV–vis (λmax, MeCN/nm): 236, 286. FTIR (KBr, cm–1): 3060, 2959–2736, 1670–1522, 1329. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 7.74–7.77 (m, 2 H), 7.69 (dd, J = 1.0 Hz, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.64 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.55–7.59 (m, 3 H), 7.28 (td, J = 1.0 Hz, J = 7.3 Hz, 1 H), 7.24 (td, J = 1.3 Hz, J = 7.3 Hz, 1 H), 4.29 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2 H), 1.64 (quint, J = 7. 5 Hz, 2 H), 1.12 (sextet, J = 7.5 Hz, 2 H), 0.74 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 3 H) ppm. 13C{1H} NMR (DMSO-d6, 125 MHz): δ = 153.1, 142.6, 135.6, 130.6, 129.7, 129.2, 128.8, 122.5, 122.0, 119.2, 110.9, 43.8, 31.2, 19.2, 13.3 ppm. HRMS (ESI): m/z calculated for C17H18N2 + H+ [M + H+]: 251.1543. Found 251.1548.

1-Pentyl-2-phenyl-1H-benzo[d]imidazole (1e)

A white solid; yield: 80%. mp 42.7–43.3 °C. UV–vis (λmax, MeCN/nm): 230, 280. FTIR (KBr, cm–1): 3064, 2971–2873, 1610–1583, 1362, 737. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 7.74–7.76 (m, 2 H), 7.69 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.63 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.55–7.59 (m,3 H), 7.28 (td, J = 1.0 Hz, J = 7.3 Hz), 7.24 (td, 1 H, J = 0.8 Hz, J = 7.3 Hz, 1 H), 4.28 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2 H), 1.65 (quint, J = 7.5 Hz, 2 H), 1.08–1.12 (m, 4 H), 0.72 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3 H) ppm. 13C{1H} NMR (DMSO-d6, 150 MHz): δ = 153.0, 142.6, 135.6, 130.6, 129.6, 129.1, 128.7, 122.3, 121.8, 119.1, 110.8, 43.9, 28.7, 28.0, 21.4, 13.6 ppm. HRMS (ESI): m/z calculated for C18H20N2 + H+ [M + H+]: 265.1699. Found 265.1710.

1-Hexyl-2-phenyl-1H-benzo[d]imidazole (1f)

Yellow oil, yield: 77%. UV–vis (λmax, MeCN/nm): 230, 280. FTIR (KBr, cm–1): ν = 3067, 2961–2862, 1617–1591, 1390, 737. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 7.74 (m, 2 H), 7.67 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.62 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.56–7.57 (m, 3 H), 7.28 (td, J = 1.2 Hz, J = 7.4 Hz, 1 H), 7.24 (td, J = 1.2 Hz, J = 7.4 Hz, 1 H), 4.28 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2 H), 1.63 (quint, J = 7.2 Hz, 2 H), 1.06–1.09 (m, 6 H), 0.73 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3 H) ppm. 13C{1H} NMR (DMSO-d6, 150 MHz): δ = 153.0, 142.5, 135.5, 130.5, 129.6, 129.1, 128.7, 122.4, 121.9, 119.1, 110.8, 43.8, 30.3, 28.8, 25.4, 21.8, 13.6 ppm. HRMS (ESI): m/z calculated for C19H22N2 + H+ [M + H+]: 279.1856. Found 279.1867.

1-Heptyl-2-phenyl-1H-benzo[d]imidazole (1g)

Yellow oil, yield: 65%. UV–vis (λmax, MeCN/nm): 230, 280. FTIR (KBr, cm–1): 3065, 2951–2860, 1614–1579, 1391, 744. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 7.73–7.75 (m, 2 H), 7.67 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.63 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.56–7.58 (m, 3 H), 7.28 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1 H), 7.24 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1 H), 4.29 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2 H), 1.64 (m, 2 H), 1.05–1.14 (m, 8 H), 0.77 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3 H) ppm. 13C{1H} NMR (DMSO-d6, 150 MHz): δ = 153.0, 142.6, 135.6, 130.6, 129.6, 129.1, 128.7, 122.4, 121.9, 119.2, 110.8, 43.9, 31.0, 28.9, 27.9, 25.8, 21.9, 13.8 ppm. HRMS (ESI): m/z calculated for C20H24N2 + H+ [M + H+]: 293.2012. Found 293.2013.

2-(4-Methoxyphenyl)-1-propyl-1H-benzo[d]imidazole (2c)

Brownish yellow oil, yield: 95%. UV–vis (λmax, MeCN/nm): 244, 290. FTIR (KBr, cm–1): 3056, 2964–2838, 1612–1574, 1251, 1028, 747. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 7.70 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2 H), 7.65 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.61 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.26 (td, J = 1.3 Hz, J = 7.4 Hz, 1 H), 7.22 (td, J = 1.2 Hz, J = 7.4 Hz, 1 H), 7.12 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2 H), 4.24 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2 H), 3.85 (s, 3 H), 1.60 (sextet, J = 7.5 Hz, 2 H), 0.74 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 3 H) ppm. 13C{1H} NMR (DMSO-d6, 125 MHz): δ = 160.2, 153.0, 142.6, 135.7, 130.5, 122.8, 122.0, 121.7, 118.9, 114.2, 110.7, 55.3, 45.6, 22.5, 10.9 ppm. HRMS (ESI): m/z calculated for C17H18N2O + H+ [M + H+]: 267.1453. Found 267.1503.

1-Butyl-2-(4-methoxyphenyl)-1H-benzo[d]imidazole (2d)

A white solid, yield: 72%. mp 71.7–72.3 °C. UV–vis (λmax, MeCN/nm): 244, 290. FTIR (KBr, cm–1): 3065–3002, 2955–2726, 1662–1578, 1330, 1027. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 7.71 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2 H), 7.65 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.60 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.26 (td, J = 1.3 Hz, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.26 (td, J = 1.3 Hz, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.21 (td, J = 1.2 Hz, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.12 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2 H), 4.28 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2 H), 3.85 (s, 3 H), 1.64 (quint, J = 7.5 Hz, 2 H), 1.15 (sextet, J = 7.5 Hz, 2 H), 0.76 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 3 H) ppm. 13C{1H} NMR (DMSO-d6, 125 MHz): δ = 160.2, 152.9, 142.6, 135.6, 130.5, 122.8, 122.0, 121.7, 118.9, 114.1, 110.6, 55.3, 43.9, 43.7, 31.2, 19.2, 13.3 ppm. HRMS (ESI): m/z calculated for C18H20N2O + H+ [M + H+]: 281.1648. Found 281.1654.

2-(4-Methoxyphenyl)-1-pentyl-1H-benzo[d]imidazole (2e)

Yellow oil, yield: 71%. UV–vis (λmax, MeCN/nm): 240, 285. FTIR (KBr, cm–1): 3052, 2959–2872, 1330, 1032, 744. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 7.70 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2 H), 7.64 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.59 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.26 (td, J = 1.2 Hz, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.22 (td, J = 1.2 Hz, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.12 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2 H), 4.27 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2 H), 3.84 (s, 3 H), 1.66 (quint, J = 7.5 Hz, 2 H), 1.09–1.16 (m, 4 H), 0.74 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3 H) ppm. 13C{1H} NMR (DMSO-d6, 150 MHz): δ = 160.2, 153.0, 142.6, 135.6, 130.6, 122.8, 122.1, 121.8, 118.9, 114.2, 110.7, 55.3, 28.7, 28.1, 21.5, 13.7 ppm. HRMS (ESI): m/z calculated for C19H22N2O + H+ [M + H+]: 295.1805. Found 295.1817.

1-Hexyl-2-(4-methoxyphenyl)-1H-benzo[d]imidazole (2f)

Yellow oil, yield: 98%. UV–vis (λmax, MeCN/nm): 241, 280. FTIR (KBr, cm–1): 3065, 2961–2862, 1661–1540, 1251, 748. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 7.69 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2 H), 7.64 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.59 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.26 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.22 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.12 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2 H), 4.27 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2 H), 3.84 (s, 3 H), 1.64 (m, 2 H), 1.07–1.14 (m, 6 H), 0.75 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3 H) ppm. 13C{1H} NMR (DMSO-d6, 150 MHz): δ = 160.2, 153.0, 142.6, 135.6, 130.5, 122.8, 122.1, 121.7, 118.9, 114.2, 110.7, 55.3, 43.9, 30.5, 28.9, 25.5, 21.9, 13.7 ppm. HRMS (ESI): m/z calculated for C20H24N2O + H+ [M + H+]: 309.1961. Found 309.1970.

1-Heptyl-2-(4-methoxyphenyl)-1H-benzo[d]imidazole (2g)

Yellowish brown oil, yield: 90%. UV–vis (λmax, MeCN/nm): 240, 285. FTIR (KBr, cm–1): 3065, 2975–2858, 1613–1533, 1391, 1259–1029, 749. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 7.70 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2 H), 7.64 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1 H), 7.60 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1 H), 7.25 (td, J = 1.2 Hz, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.21 (td, J = 1.0 Hz, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.12 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2 H), 4.28 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2 H), 3.85 (s, 3 H), 1.64 (quint, J = 7.0 Hz, 2 H), 1.09–1.11 (m, 8 H), 0.79 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3 H) ppm. 13C{1H} NMR (DMSO-d6, 150 MHz): δ = 160.2, 152.9, 142.6, 135.6, 130.5, 122.8, 122.0, 121.7, 118.9, 114.1, 110.6, 55.3, 43.8, 31.0, 28.9, 27.9, 25.8, 25.8, 21.9, 13.8 ppm. HRMS (ESI): m/z calculated for C21H26N2O + H+ [M + H+]: 323.2124. Found 323.212.

1-Propyl-2-(2-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-1H-benzo[d]imidazole (3c)

Yellow oil, yield: 98%. UV–vis (λmax, MeCN/nm): 257, 276, 283. FTIR (KBr cm–1): 3062, 2970–2879, 1650–1583, 1315, 1171, 747. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 7.96 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.84–7.88 (m, 1 H), 7.81–7.83 (m, 1 H), 7.75 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 1 H), 7.68 (m, 2 H), 7.30–7.33 (m, 1 H), 7.24–7.28 (m, 1 H), 3.96 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2 H), 1.58 (sextet, J = 7.5 Hz, 2 H), 0.71 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 3 H) ppm. 13C{1H} NMR (DMSO-d6, 125 MHz): δ = 149.82, 142.40, 134.72, 132.44, 132.24, 130.71, 129.00, 128.88, 128.86, 128.76, 128.52, 128.28, 126.90, 126.79, 126.75, 126.71, 124.72, 122.63, 122.55, 121.89, 119.37, 110.88, 45.37, 22.28, 10.90 ppm. HRMS (ESI): m/z calculated for C17H15F3N2 + H+ [M + H+]: 305.1221. Found 305.1270.

1-Butyl-2-(2-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-1H-benzo[d]imidazole (3d)

Dark yellow oil, yield: 92%. UV–vis (λmax, MeCN/nm): 257, 276, 283. FTIR (KBr, cm–1): 3062, 2962–2874, 1650–1583, 1315, 1171, 746. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 7.98 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.88 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 1 H), 7.81 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.72 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1 H), 7.70 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1 H), 7.66 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1 H), 7.30–7.33 (m, 1 H), 7.24–7.28 (m, 1 H), 4.00 (t, J = 7 .5 Hz, 2 H), 1.55 (quint, J = 8 .0 Hz, 2 H), 1.12 (sextet, J = 7.5 Hz, 2 H), 0.71 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 3 H) ppm. 13C{1H} NMR (DMSO-d6, 125 MHz): δ = 149.88, 142.49, 134.73, 132.54, 132.31, 130.82, 129.10, 128.88, 128.86, 128.61, 128.37, 126.99, 126.93, 126.89, 126.85, 126.82, 124.81, 122.76, 122.63, 122.00, 119.45, 110.91, 43.57, 31.02, 19.22, 13.32 ppm. HRMS (ESI): m/z calculated for C18H17F3N2 + H+ [M + H+]: 319.1417. Found 319.1425.

1-Pentyl-2-(2-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-1H-benzo[d]imidazole (3e)

Yellow oil, yield: 97%. UV–vis (λmax, MeCN/nm): 251, 271, 277. FTIR (KBr, cm–1): 3063, 2964–2878, 1611–1532, 1313, 1180, 745; 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 7.97 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.86 (td, J = 0.8 Hz, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.82 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.71 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1 H), 7.68 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.64 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.31 (td, J = 0.8 Hz, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.26 (td, J = 1.0 Hz, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 3.99 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 2 H), 1.55 (quint, J = 6.9 Hz, 2 H), 1.07–1.10 (m, 4 H), 0.70 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3 H) ppm. 13C{1H} NMR (DMSO-d6, 150 MHz): δ = 149.80, 142.37, 134.65, 132.48, 132.22, 130.78, 128.94, 128.77, 128.74, 128.54, 128.34, 126.88, 126.85, 126.82, 126.79, 124.55, 122.73, 121.96, 119.37, 110.83, 43.68, 28.44, 27.95, 21.40, 13.52 ppm. HRMS (ESI): m/z calculated for C19H19F3N2 + H+ [M + H+]: 333.1573. Found 333.1583.

1-Hexyl-2-(2-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-1H-benzo[d]imidazole (3f)

Yellow oil, yield: 69%. UV–vis (λmax, MeCN/nm): 251, 271, 278. FTIR (KBr, cm–1): 3065, 2956–2856, 1609–1587, 1315, 1172, 747. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 7.98 (d, 1 H, J = 7.8 Hz), 7.86 (td, J = 1.0 Hz, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.83 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.72 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1 H), 7.69 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1 H), 7.65 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.31 (td, J = 1.0 Hz, J = 7.6 Hz, 1 H), 7.26 (td, J = 0.8 Hz, J = 8.0 Hz, 1 H), 4.00 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 2 H), 1.55 (quint, J = 7.2 Hz, 2 H), 1.03–1.12 (m, 6 H), 0.74 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3 H) ppm. 13C{1H} NMR (DMSO-d6, 150 MHz): δ = 149.78, 142.45, 134.67, 132.45, 132.25, 130.72, 128.97, 128.87, 128.86, 128.77, 128.57, 128.37, 126.87, 126.84, 126.81, 126.77, 126.38, 124.56, 122.75, 122.66, 121.90, 119.40, 110.82, 43.69, 30.47, 28.72, 25.48, 21.72, 13.72 ppm. HRMS (ESI): m/z calculated for C20H21F3N2 + H+ [M + H+]: 347.173. Found 347.1742.

1-Heptyl-2-(2-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-1H-benzo[d]imidazole (3g)

Yellow oil, yield: 89%. UV–vis (λmax, MeCN/nm): 250, 271, 277. FTIR (KBr, cm–1): 3062, 2937–2855, 1608–1534, 1313, 1169, 746. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 7.98 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1 H), 7.87 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1 H), 7.83 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.73 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1 H), 7.69 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.66 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1 H), 7.32 (td, J = 1.2 Hz, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.26 (td, J = 1.2 Hz, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 4.00 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2 H), 1.56 (quint, J = 7.2 Hz, 2 H), 1.07–1.13 (m, 8 H), 0.78 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3 H) ppm. 13C{1H} NMR (DMSO-d6, 150 MHz): δ = 149.73, 142.43, 134.64, 132.42, 132.22, 130.69, 128.86, 128.85, 128.72, 128.52, 126.84, 126.81, 126.78, 126.76, 124.53, 122.72, 122.61, 121.85, 119.37, 110.80, 43.62, 30.81, 28.68, 27.86, 25.70, 21.87, 13.80 ppm. HRMS (ESI): m/z calculated for C21H23F3N2 + H+ [M + H+]: 361.1886. Found 361.1887.

Antiproliferative Activity

All synthesized compounds were evaluated for cytotoxicity on the MDA-MB-231 cell line by using sulforhodamine B (SRB) assay as described by Skehan et al.62 Four concentrations of positive control from 100 to 0.8 μM were prepared in DMSO (1%). After being dissolved in DMSO, the test compound was added to each well of the 96-well culture plate. DMSO (10%) and camptothecin were added to each negative- and positive-control well, respectively. The cells were dissociated by trypsin. Subsequently, cell concentration was determined by counting in a hematocytometer chamber to adjust the cell density, and 190 μL cell suspension was taken into the prepared assay plates. The plates containing only the cell suspension were set aside for a no-growth control (day 0) and treated with 20% TCA for fixation after 1 h of incubation. The remaining plates were incubated for 72 h, and the cells were fixed with TCA for 1 h. The TCA-fixed cells stained with SRB dye for 30 min at 37 °C were rinsed three times with 1% acetic acid to remove the unbound dye and air-dried at room temperature. The protein-bound dye was solubilized in a 10 mM unbuffered Tris base, and the plates were shaken slightly for 10 min. The OD was measured by an ELISA plate reader (Biotek) at 540 nm. The percentage of cell-growth inhibition was calculated using the following formula:

Each experiment was performed in triplicate to define the IC50 values by using the calculation software TableCure2D version 4.

In Vitro Antibacterial and Antifungal Activities

The bacterial strains, such as E. coli (ATCC 25922), P. aeruginosa (ATCC 27853), S. faecalis (ATCC 29212), S. aureus (ATCC 29213), and MRSA (ATCC 43300), and the fungal strains, such as C. albicans (ATCC 10231) and A. niger (ATCC 16404), used for this study were provided by the Pharmaceutical Biotechnology Laboratory, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Medicine & Pharmacy at HCMC. Initially, the antimicrobial activity was determined using the agar disc diffusion method in accordance with the guidelines of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute63−66 with positive controls (amikacin for antibacterial activity and ketoconazole for antifungal activity), and DMSO was used as a negative control. The prepared bacterial and fungal inoculums were swabbed onto each Mueller–Hinton agar plate. Paper discs impregnated with test compounds (50 μL) were pressed down to ensure their contact with the medium surface. All plates inoculated with bacteria and fungi were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h and 30 °C for 48 h, respectively. The inhibition zones in millimeters (including wells) were measured using a caliper. If the diameter of inhibition was greater than 8 mm, the compound was considered active. Then, MIC was determined for the active molecules observed during the test above. The tested samples and positive controls were prepared in the media by twofold serial dilution to achieve the different concentration gradients of 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256, 512, and 1024 μg mL–1 and allowed to interact with microorganism strains. After incubation, the MIC value was read and defined as the lowest concentration of an antimicrobial agent that completely inhibited the visible growth of microorganisms.

Molecular Docking

Preparation of Ligands

The 2D and 3D chemical structures of 2g, amikacin, and XCF were constructed using the programs ChemDraw 19.1 and MOE 2015.10, respectively. The Energy Minimization and Molecular Dynamic routines in Sybyl-X 1.167 were used to improve the ligand structures. Conj Grad and Gasteiger–Huckel charges were employed in the energy minimization process, and the process was terminated when the minimum energy change reached 0.001 kcal mol–1 with a maximum number of iterations set to 10,000. The ligands were also heated to 700 K in 1000 fs by using the simulated annealing approach, and then they were cooled to 200 K in the same time frame to achieve their final conformations in the stable states. This process underwent five cycles to obtain the final ligand conformations with minimal energy.

Method Used to Produce Protein

The receptor model was derived from the Protein Data Bank by using the X-ray crystallographic structure of co-crystallized DHFR-NADPH associated with the inhibitor XCF (PDB ID: 3FYV). Using the QuickPrep tool in MOE 2015.10, the 3D protein structure was hydrogenated and protonated, and the unbound water was removed. The BiosolveIT LeadIT 2.1.8 program was then used to import this structure.68 The reference ligand (XCF) was used to set the active site’s radius sphere to 6.5, with the ligand at the center.

Docking Evaluation

Redocking was performed to confirm the docking procedure. XCF was redocked into the active site of the DHFR-NADPH complex after being exported from the crystallographic structure. The RMSD between the native conformation and the best redocked one shows a successful docking strategy; that is, a value of less than 2.0 indicates a successful docking technique.69,70 BiosolveIT LeadIT 2.1.8 was used for the docking procedure, and the following settings were set: the maximum number of solutions per iteration (1000), the maximum number of solutions per fragmentation (200), and the number of poses to maintain for interaction analysis (1 – top 1). The Discovery Studio 4.0 client software was used to visualize the 3D poses of the ligands with the DHFR-NADPH complex.71

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the project under serial number QTBY01.04/23-24.

Glossary

ABBREVIATIONS

- IC50

half-maximal inhibitory concentration

- MIC

minimal inhibitory concentration

- μM

micromolar

- DHFR

dihydrofolate reductase

- XCF

iclaprim

- DMC

dimethyl carbonate

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- TNBC

triple-negative breast cancer

- FTIR

Fourier transform infrared

- HRMS

high-resolution mass spectrometry

- MRSA

methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

- NADPH

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate

- TLC

thin layer chromatography

- CYP51

cytochrome P450 14α-sterol demethylase

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.3c03530.

1H NMR, 13C NMR, UV–vis, FITR, HRMS, and HPLC analysis results of all synthesized compounds (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Hsieh C.-Y.; Ko P.-W.; Chang Y.-J.; Kapoor M.; Liang Y.-C.; Chu H.-L.; Lin H.-H.; Horng J.-C.; Hsu M.-H. Design and synthesis of benzimidazole-chalcone derivatives as potential anticancer agents. Molecules 2019, 24, 3259. 10.3390/molecules24183259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satija G.; Sharma B.; Madan A.; Iqubal A.; Shaquiquzzaman M.; Akhter M.; Parvez S.; Khan M. A.; Alam M. M. Benzimidazole based derivatives as anticancer agents: Structure activity relationship analysis for various targets. J. Heterocycl. 2022, 59, 22–66. 10.1002/jhet.4355. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kelishadi R.; Farajian S. The protective effects of breastfeeding on chronic non-communicable diseases in adulthood: A review of evidence. Adv. Biomed. Res. 2014, 3, 3. 10.4103/2277-9175.124629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khabnadideh S.; Rezaei Z.; Pakshir K.; Zomorodian K.; Ghafari N. Synthesis and antifungal activity of benzimidazole, benzotriazole and aminothiazole derivatives. Res. Pharm. Sci. 2012, 7, 65–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim H. A.; Refaat H. M. Versatile mechanisms of 2-substituted benzimidazoles in targeted cancer therapy. Future J. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 6, 1–20. 10.1186/s43094-020-00048-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cao W.; Chen H.-D.; Yu Y.-W.; Li N.; Chen W.-Q. Changing profiles of cancer burden worldwide and in China: a secondary analysis of the global cancer statistics 2020. Chin. Med. J. 2021, 134, 783–791. 10.1097/CM9.0000000000001474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giaquinto A. N.; Sung H.; Miller K. D.; Kramer J. L.; Newman L. A.; Minihan A.; Jemal A.; Siegel R. L. Breast cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2022, 72, 524–541. 10.3322/caac.21754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens K. N.; Vachon C. M.; Couch F. J. Genetic susceptibility to triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2013, 73, 2025–2030. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamanna K., Synthesis and pharmacological profile of benzimidazoles. In Chemistry and applications of benzimidazole and its derivatives .London, UK:IntechOpen, 2019; pp. 51–69. [Google Scholar]

- Shrivastava N.; Naim M. J.; Alam M. J.; Nawaz F.; Ahmed S.; Alam O. Benzimidazole scaffold as anticancer agent: synthetic approaches and structure–activity relationship. Arch. Pharm. 2017, 350, e201700040 10.1002/ardp.201700040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhutani P.; Joshi G.; Raja N.; Bachhav N.; Rajanna P. K.; Bhutani H.; Paul A. T.; Kumar R. US FDA approved drugs from 2015–June 2020: A perspective. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 2339–2381. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c01786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haider K.; Yar M. S., Advances of benzimidazole derivatives as anticancer agents: Bench to bedside. 2022; p 3.

- Ates-Alagoz Z. Antimicrobial activities of 1-H-Benzimidazole-based molecules. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2016, 16, 2953–2962. 10.2174/1568026616666160506130226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ersan R. H.; Kuzu B.; Yetkin D.; Alagoz M. A.; Dogen A.; Burmaoglu S.; Algul O. 2-phenyl substituted benzimidazole derivatives: Design, synthesis, and evaluation of their antiproliferative and antimicrobial activities. Med. Chem. Res. 2022, 31, 1192–1208. 10.1007/s00044-022-02900-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhari S. R.; Patil P. N.; Patil U. K.; Patel H. M.; Rajput J. D.; Pawar N. S.; Patil D. B. Green synthesis of N-substituted benzimidazoles: The promising methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) inhibitors. Chem. Data Collect. 2020, 25, 100344 10.1016/j.cdc.2020.100344. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shalaby M.-A. W.; Dokla E. M.; Serya R. A.; Abouzid K. A. Identification of novel pyrazole and benzimidazole based derivatives as PBP2a inhibitors: Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation. Arch. Pharm. Sci. Ain Shams univ. 2019, 3, 228–245. 10.21608/aps.2019.16625.1010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Woolley D. W. Some biological effects produced by benzimidazole and their reversal by purines. J. Biol. Chem. 1944, 152, 225–232. 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)72045-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gaba M.; Mohan C. Development of drugs based on imidazole and benzimidazole bioactive heterocycles: recent advances and future directions. Med. Chem. Res. 2016, 25, 173–210. 10.1007/s00044-015-1495-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keller P.; Müller C.; Engelhardt I.; Hiller E.; Lemuth K.; Eickhoff H.; Wiesmüller K.-H.; Burger-Kentischer A.; Bracher F.; Rupp S. An antifungal benzimidazole derivative inhibits ergosterol biosynthesis and reveals novel sterols. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 6296–6307. 10.1128/AAC.00640-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafiei M.; Peyton L.; Hashemzadeh M.; Foroumadi A. History of the development of antifungal azoles: A review on structures, SAR, and mechanism of action. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2020, 104, 104240. 10.1016/j.bioorg.2020.104240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solana H. D.; Rodriguez J. A.; Lanusse C. E. Comparative metabolism of albendazole and albendazole sulphoxide by different helminth parasites. Parasitol. Res. 2001, 87, 275–280. 10.1007/PL00008578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y.; Ong Y. C.; Keller S.; Karges J.; Bouchene R.; Manoury E.; Blacque O.; Müller J.; Anghel N.; Hemphill A.; Häberli C.; Taki A. C.; Gasser R. B.; Cariou K.; Keiser J.; Gasser G. Synthesis, characterization and antiparasitic activity of organometallic derivatives of the anthelmintic drug albendazole. Dalton Trans. 2020, 49, 6616–6626. 10.1039/D0DT01107J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawluk S. A.; Roels C. A.; Wilby K. J.; Ensom M. H. H. A review of pharmacokinetic drug–drug interactions with the anthelmintic medications albendazole and mebendazole. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2015, 54, 371–383. 10.1007/s40262-015-0243-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pene P.; Mojon M.; Garin J.; Coulaud J.; Rossignol J. Albendazole: a new broad spectrum anthelmintic. Double-blind multicenter clinical trial. Am. J. Trop. 1982, 31, 263–266. 10.4269/ajtmh.1982.31.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariappan G.; Hazarika R.; Alam F.; Karki R.; Patangia U.; Nath S. Synthesis and biological evaluation of 2-substituted benzimidazole derivatives. Arab. J. Chem. 2015, 8, 715–719. 10.1016/j.arabjc.2011.11.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pham E. C.; Le T. V. T.; Truong T. N. Design, synthesis, bio-evaluation, and in silico studies of some N-substituted 6-(chloro/nitro)-1H-benzimidazole derivatives as antimicrobial and anticancer agents. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 21621–21646. 10.1039/D2RA03491C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oefner C.; Parisi S.; Schulz H.; Lociuro S.; Dale G. E. Inhibitory properties and X-ray crystallographic study of the binding of AR-101, AR-102 and iclaprim in ternary complexes with NADPH and dihydrofolate reductase from Staphylococcus aureus. Acta Crys. 2009, 65, 751–757. 10.1107/S0907444909013936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawser S.; Lociuro S.; Islam K. Dihydrofolate reductase inhibitors as antibacterial agents. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2006, 71, 941–948. 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouk S.; Thiébaud S.; Borredon E.; Chabaud B. N-Methylation of nitrogen-containing heterocycles with dimethyl carbonate. Synth. Commun. 2005, 35, 3021–3026. 10.1080/00397910500278578. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y.-Q.; Jia S.-H.; Li X.-Y.; Sun Y.-M.; Li W.; Zhang W.-W.; Xu G.-Q. An efficient NaHSO3-promoted protocol for chemoselective synthesis of 2-substituted benzimidazoles in water. Chem. Pap. 2018, 72, 1265–1276. 10.1007/s11696-017-0367-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ansari K. F.; Lal C. Synthesis, physicochemical properties and antimicrobial activity of some new benzimidazole derivatives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 44, 4028–4033. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2009.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shruthi N.; Poojary B.; Kumar V.; Hussain M. M.; Rai V. M.; Pai V. R.; Bhat M.; Revannasiddappa B. C. Novel benzimidazole–oxadiazole hybrid molecules as promising antimicrobial agents. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 8303–8316. 10.1039/C5RA23282A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sontakke V. A.; Lawande P. P.; Kate A. N.; Khan A.; Joshi R.; Kumbhar A. A.; Shinde V. S. Antiproliferative activity of bicyclic benzimidazole nucleosides: synthesis, DNA-binding and cell cycle analysis. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2016, 14, 4136–4145. 10.1039/C6OB00527F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamal A.; Ponnampalli S.; Vishnuvardhan M. V. P. S.; Rao M. P. N.; Mullagiri K.; Nayak V. L.; Chandrakant B. Synthesis of imidazothiadiazole–benzimidazole conjugates as mitochondrial apoptosis inducers. Med.Chem.Commun. 2014, 5, 1644–1650. 10.1039/C4MD00219A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Atmaca H.; İlhan S.; Batır M. B.; Pulat Ç. Ç.; Güner A.; Bektaş H. Novel benzimidazole derivatives: Synthesis, in vitro cytotoxicity, apoptosis and cell cycle studies. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2020, 327, 109163 10.1016/j.cbi.2020.109163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blagosklonny M. V.; Pardee A. B. The restriction point of the cell cycle. Cell Cycle 2002, 1, 102–109. 10.4161/cc.1.2.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swathantraiah J. G.; Srinivasa S. M.; Belagal Motatis A. K.; Uttarkar A.; Bettaswamygowda S.; Thimmaiah S. B.; Niranjan V.; Rangappa S.; Subbegowda R. K.; Ramegowda T. N. Novel 1, 2, 5-trisubstituted benzimidazoles potentiate apoptosis by mitochondrial dysfunction in panel of cancer cells. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 46955–46971. 10.1021/acsomega.2c06057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinou J.-C.; Youle R. J. Mitochondria in apoptosis: Bcl-2 family members and mitochondrial dynamics. Dev. Cell 2011, 21, 92–101. 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W.-Y.; Yi Q.-Y.; Wang Y.-J.; Du F.; He M.; Tang B.; Wan D.; Liu Y.-J.; Huang H.-L. Photoinduced anticancer activity studies of iridium (III) complexes targeting mitochondria and tubules. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 151, 568–584. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makvandi P.; Josic U.; Delfi M.; Pinelli F.; Jahed V.; Kaya E.; Ashrafizadeh M.; Zarepour A.; Rossi F.; Zarrabi A. Drug delivery (nano) platforms for oral and dental applications: tissue regeneration, infection control, and cancer management. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, 2004014. 10.1002/advs.202004014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Güzel E.; Acar Çevik U.; Evren A. E.; Bostancı H. E.; Gül Ü. D.; Kayış U.; Özkay Y.; Kaplancıklı Z. A. Synthesis of benzimidazole-1, 2, 4-triazole derivatives as potential antifungal agents targeting 14α-demethylase. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 4369–4384. 10.1021/acsomega.2c07755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng C.; Che X.; Wang W.; Wang S.; Cao Y.; Yao J.; Miao Z.; Zhang W. Design and synthesis of antifungal benzoheterocyclic derivatives by scaffold hopping. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 46, 1706–1712. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2011.01.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Çevik U. A.; Celik I.; Işık A.; Pillai R. R.; Tallei T. E.; Yadav R.; Özkay Y.; Kaplancıklı Z. A. Synthesis, molecular modeling, quantum mechanical calculations and ADME estimation studies of benzimidazole-oxadiazole derivatives as potent antifungal agents. J. Mol. Struct. 2022, 1252, 132095 10.1016/j.molstruc.2021.132095. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kankate R. S.; Gide P. S.; Belsare D. P. Design, synthesis and antifungal evaluation of novel benzimidazole tertiary amine type of fluconazole analogues. Arab. J. Chem. 2019, 12, 2224–2235. 10.1016/j.arabjc.2015.02.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yin W.; Cui H.; Jiang H.; Zhang Y.; Liu L.; Wu T.; Sun Y.; Zhao L.; Su X.; Zhao D.; Cheng M. Broadening antifungal spectrum and improving metabolic stablity based on a scaffold strategy: Design, synthesis, and evaluation of novel 4-phenyl-4, 5-dihydrooxazole derivatives as potent fungistatic and fungicidal reagents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 227, 113955 10.1016/j.ejmech.2021.113955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun S.; Yan J.; Tai L.; Chai J.; Hu H.; Han L.; Lu A.; Yang C.; Chen M. Novel (Z)/(E)-1, 2, 4-triazole derivatives containing oxime ether moiety as potential ergosterol biosynthesis inhibitors: design, preparation, antifungal evaluation, and molecular docking. Mol. Diversity 2023, 27, 145–157. 10.1007/s11030-022-10412-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues M. L. The multifunctional fungal ergosterol. MBio 2018, 9, e01755-18 10.1128/mbio.01755-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Can N. Ö.; Acar Çevik U.; Saǧlık B. N.; Levent S.; Korkut B.; Özkay Y.; Kaplancıklı Z. A.; Koparal A. S. Synthesis, molecular docking studies, and antifungal activity evaluation of new benzimidazole-triazoles as potential lanosterol 14α-demethylase inhibitors. J. Chem. 2017, 2017, 1. 10.1155/2017/9387102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nehra N.; Tittal R. K.; Vikas D. G.; Naveen; Lal K. Synthesis, antifungal studies, molecular docking, ADME and DNA interaction studies of 4-hydroxyphenyl benzothiazole linked 1, 2, 3-triazoles. J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1245, 131013 10.1016/j.molstruc.2021.131013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Evrard A.; Siomenan C.; Etienne C. T.; Daouda T.; Souleymane C.; Drissa S.; Ané A. Design, synthesis and in vitro antibacterial activity of 2-thiomethyl-benzimidazole derivatives. Adv. Biol. Chem. 2021, 11, 165–177. 10.4236/abc.2021.114012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ansari K.; Lal C.; Khitoliya R. Synthesis and biological activity of some triazole-bearing benzimidazole derivatives. J. Serbian Chem. Soc. 2011, 76, 341–352. 10.2298/JSC100301029A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elamin M.; Zubair U.; Abdullah A. A.-B. Antibacterial and antifungal activities of benzimidazole and benzoxazole derivatives. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1981, 19, 29–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeyakkumar P.; Zhang L.; Avula S. R.; Zhou C.-H. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of berberine-benzimidazole hybrids as new type of potentially DNA-targeting antimicrobial agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 122, 205–215. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ul Huda N.; Islam S.; Zia M.; William K.; Abbas F.; Umar M. I.; Iqbal M. A.; Mannan A. Anticancer, antimicrobial and antioxidant potential of sterically tuned bis-N-heterocyclic salts. Z. Naturforsch., C 2019, 74, 17–23. 10.1515/znc-2018-0095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bansal Y.; Silakari O.; Lapinsky D. J.; Kusayanagi T.; Tsukuda S.; Shimura S.; Manita D.; Iwakiri K.; Kamisuki S.; Takakusagi Y.; Takeuchi T. The therapeutic journey of benzimidazoles: A review pp 6208-6236. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2012, 20, 6199–6207. 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandyopadhyay P.; Sathe M.; Ponmariappan S.; Sharma A.; Sharma P.; Srivastava A. K.; Kaushik M. P. Exploration of in vitro time point quantitative evaluation of newly synthesized benzimidazole and benzothiazole derivatives as potential antibacterial agents. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 21, 7306–7309. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mai-Prochnow A.; Clauson M.; Hong J.; Murphy A. B. Gram positive and Gram negative bacteria differ in their sensitivity to cold plasma. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 1–11. 10.1038/srep38610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquina-Lemonche L.; Burns J.; Turner R. D.; Kumar S.; Tank R.; Mullin N.; Wilson J. S.; Chakrabarti B.; Bullough P. A.; Foster S. J.; Hobbs J. K. The architecture of the Gram-positive bacterial cell wall. Nature 2020, 582, 294–297. 10.1038/s41586-020-2236-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Shea R.; Moser H. E. Physicochemical properties of antibacterial compounds: Implications for drug discovery. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 2871–2878. 10.1021/jm700967e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oefner C.; Bandera M.; Haldimann A.; Laue H.; Schulz H.; Mukhija S.; Parisi S.; Weiss L.; Lociuro S.; Dale G. E. Increased hydrophobic interactions of iclaprim with Staphylococcus aureus dihydrofolate reductase are responsible for the increase in affinity and antibacterial activity. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2009, 63, 687–698. 10.1093/jac/dkp024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh T.-K.-C.; Nguyen T.-H.-A.; Tran N.-H.-S.; Nguyen T.-D.; Hoang T.-K.-D. A facile and efficient synthesis of benzimidazole as potential anticancer agents. J. Chem. Sci. 2020, 132, 84. 10.1007/s12039-020-01783-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Skehan P.; Storeng R.; Scudiero D.; Monks A.; McMahon J.; Vistica D.; Warren J. T.; Bokesch H.; Kenney S.; Boyd M. R. New colorimetric cytotoxicity assay for anticancer-drug screening. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1990, 82, 1107–1112. 10.1093/jnci/82.13.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLSI ., Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria That Grow Aerobically. 11th ed. CLSI standard M07. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- CLSI ., Performance Standards for Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Filamentous Fungi. 2nd ed. CLSI supplement M60. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- CLSI ., Performance Standards for Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Yeasts. PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute;: 2nd ed. CLSI supplement M60. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- CLSI ., Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. 31st ed. CLSI supplement M100. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sybyl-X Molecular Modeling Software Packages, Version 1.1; TRIPOS Associates, Inc.: Louis: USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- LeadIT, Version 2.1.8; BioSolveIT-GmbH: Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hevener K. E.; Zhao W.; Ball D. M.; Babaoglu K.; Qi J.; White S. W.; Lee R. E. Validation of molecular docking programs for virtual screening against dihydropteroate synthase. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2009, 49, 444–460. 10.1021/ci800293n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran T.-S.; Le M.-T.; Tran T.-D.; Tran T.-H.; Thai K.-M. Design of curcumin and flavonoid derivatives with acetylcholinesterase and beta-secretase inhibitory activities using in silico approaches. Molecules 2020, 25, 3644. 10.3390/molecules25163644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Accelrys Discovery Studio 4.0 Client, Dassault Systemes BIOVIA: Vélizy-Villacoublay: France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.