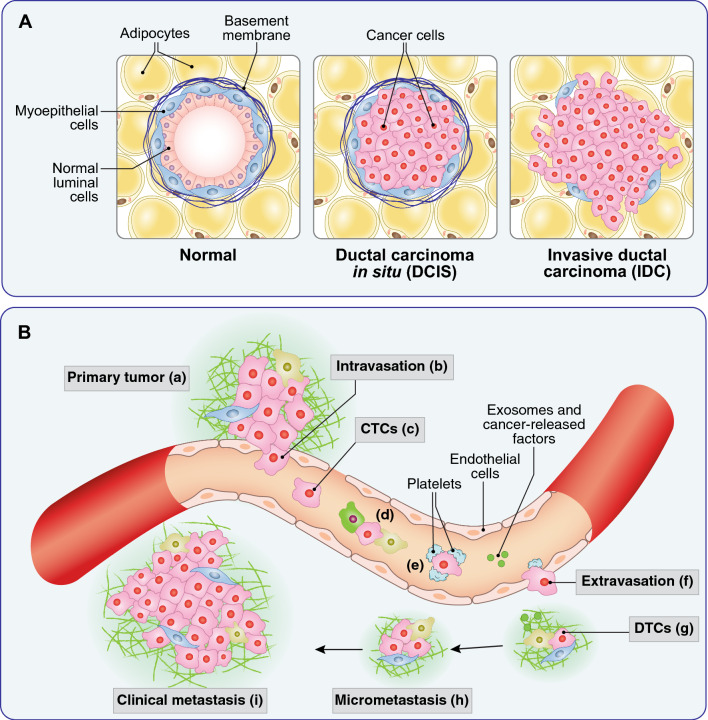

Fig. 3.

BC invasiveness and metastasis. A From DCIS to IDC. In the normal breast gland (left), two ordered layers of luminal and myoepithelial cells are present, separated from the surrounding stroma by a basement membrane. In DCIS (center) cancer cells proliferate and fill the lumen, while remaining confined by an intact myoepithelial–basement membrane barrier. In IDC (right), cancer cells penetrate into the surrounding stroma, with loss of the basement membrane and of the myoepithelial barrier. B Metastasis as a multistep process. Locally invasive cancer cells from the primary tumor (a) are able to intravasate into the local circulation (b) also because of the poor structure of the neo-formed tumor vessels that present fenestrations with interruption of the endothelial and pericyte (not shown) layers. Once in the bloodstream, cancer cells are defined circulating tumor cells (CTC, c). In the bloodstream, CTCs need to survive shear stress and predation by immune cells (d), which they do also with the aid of a platelet coat (e). In distant organs, CTCs attach to endothelial cells and extravasate (f) becoming disseminated tumor cells (DTCs, g). The settlement in the distant organs (micrometastasis, h) is facilitated by cancer-released exosomes and factors (g, green dots) that prepare the so-called pre-metastatic niche. Micrometastases can remain dormant for long periods of time, before being reactivated and giving raise to macrometastases or clinically detectable metastases (i). Each single step of the metastatic process is accompanied to distinct metabolic changes, reviewed extensively in [170]