Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

To investigate temporal trends and outcomes associated with early antibiotic prescribing in patients hospitalized with COVID-19.

DESIGN:

Retrospective propensity-matched cohort study using the National COVID Cohort Collaborative (N3C) database.

SETTING:

Sixty-six health systems throughout the United States that were contributing to the N3C database. Centers that had fewer than 500 admissions in their dataset were excluded.

PATIENTS:

Patients hospitalized with COVID-19 were included. Patients were defined to have early antibiotic use if they received at least 3 calendar days of intravenous antibiotics within the first 5 days of admission.

INTERVENTIONS:

None.

MEASUREMENTS AND MAIN RESULTS:

Of 322,867 qualifying first hospitalizations, 43,089 patients received early empiric antibiotics. Antibiotic use declined across all centers in the data collection period, from March 2020 (23%) to June 2022 (9.6%). Average rates of early empiric antibiotic use (EEAU) also varied significantly between centers (deviance explained 7.33% vs 20.0%, p < 0.001). Antibiotic use decreased slightly by day 2 of hospitalization and was significantly reduced by day 5. Mechanical ventilation before day 2 (odds ratio [OR] 3.57; 95% CI, 3.42–3.72), extracorporeal membrane oxygenation before day 2 (OR 2.14; 95% CI, 1.75–2.61), and early vasopressor use (OR 1.85; 95% CI, 1.78–1.93) but not region of residence was associated with EEAU. After propensity matching, EEAU was associated with an increased risk for in-hospital mortality (OR 1.27; 95% CI, 1.23–1.33), prolonged mechanical ventilation (OR 1.65; 95% CI, 1.50–1.82), late broad-spectrum antibiotic exposure (OR 3.24; 95% CI, 2.99–3.52), and late Clostridium difficile infection (OR 1.60; 95% CI, 1.37–1.87).

CONCLUSIONS:

Although treatment of COVID-19 patients with empiric antibiotics has declined during the pandemic, the frequency of use remains high. There is significant inter-center variation in antibiotic prescribing practices and evidence of potential harm. Our findings are hypothesis-generating and future work should prospectively compare outcomes and adverse events.

Keywords: antimicrobial prescribing, bacterial coinfection, COVID-19, drug resistance, pneumonia

KEY POINTS

Question: How did empiric antibiotic prescribing vary between centers during the COVID-19 pandemic and is there evidence of harm?

Findings: In this retrospective cohort study that analyzed 322,867 hospital admissions, we found that early empiric antibiotic use declined over the course of the pandemic but remains higher than the reported incidence of bacterial coinfections. Early empiric antibiotic use was associated with increased mortality, prolonged mechanical ventilation, Clostridium difficile infection, and later broad-spectrum antibiotic exposure.

Meanings: Decreasing amounts of empiric antibiotic prescriptions over time and high levels of variation between centers likely reflect uncertainty about the utility of empiric antibiotics in patients hospitalized with COVID-19. There is suggestion that empiric antibiotics are associated with harm. Future work should examine the outcomes associated with early empiric antibiotic use.

The appropriate use of empiric antibiotics is a clinical challenge for patients with severe COVID-19. Early in the pandemic, there was concern that bacterial coinfection would influence morbidity and mortality. Evidence from prior pandemics supported this claim. Most deaths during the 1918 influenza pandemic were due to bacterial coinfections (1). Similarly, in the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic, 29–59% of worldwide mortality was due to bacterial superinfections (2). Fortunately, early data from the COVID-19 pandemic suggests bacterial coinfection is uncommon. A meta-analysis of 3,338 patients with COVID-19 found that only 3.5% of patients had bacterial coinfection on presentation. The rate of bacterial coinfection was higher, 8.1%, among patients requiring intensive care (3). Studies thus far have demonstrated that 76% of hospitalized COVID-19 patients receive antibiotics (4). As demonstrated by previous studies, early empiric antibiotic use (EEAU) is not without risk. Extended use of empiric antibiotics is associated with increased antibiotic resistance (5), Clostridioides difficile infection (6), and mortality (7). Experimental animal data and observational human data suggest that early anaerobic antibiotics alter the pulmonary microbiome, increase lethality of hyperoxia, and are associated with adverse patient outcomes (8). Alterations in the respiratory microbiome have been observed in prolonged acute respiratory distress syndrome in COVID-19 (9). We hypothesized that: 1) rates of EEAU would vary between centers and decrease over time and 2) EEAU would be associated with increased rates of C. difficile infection, antimicrobial resistance, and mortality.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This article was written using The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Guidelines (10), and authorship was determined using International Committee of Medical Journal Editors recommendations. We used level 3 (limited dataset) from the National COVID Cohort Collaborative (N3C) (11) to obtain the patient data for this study (N3C DUR-981EAC4).

The analyses described in this publication were conducted with data or tools accessed through the NCATS N3C Data Enclave (https://covid.cd2h.org) and N3C Attribution and Publication Policy v 1.2-2020-08-25b supported by NCATS U24 TR002306. This research was possible because of the patients whose information is included within the data and the organizations (https://ncats.nih.gov/n3c/resources/data-contribution/data-transfer-agreement-signatories) and scientists who have contributed to the ongoing development of this community resource (11). N3C Logic Liaison templates were used to generate study variables. The Logic Liaisons are supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers UL1TR003015 and U24TR002306.

The code to support this analysis is available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6448407. This Institutional Review Board for Health Sciences Research at The University of Virginia determined that this work was nonhuman subjects research and that no review was required. A detailed description of methods, including codes and imputation strategies used, is available in Supplementary Methods (http://links.lww.com/CCM/H339).

Participants

In this, retrospective, propensity score-matched cohort study, we identified the first hospital admission between March 2020 and June 2022 for patients with a positive COVID-19 PCR or antigen test within 48 hours of admission or 15 days before admission. We excluded patients admitted to centers with fewer than a total of 500 admissions in the dataset (eFig. 1, http://links.lww.com/CCM/H339).

Exposures

We defined early empiric antibiotic use as at least 3 calendar days of administered parenteral antibiotics within the first 5 days of admission. We chose this definition to capture antibiotics started when culture data were unlikely to be available.

Outcomes

Our primary outcome was in-hospital mortality. Our secondary outcomes were late exposure to extended-spectrum antibiotics (defined as receiving a parenteral carbapenem or aminoglycoside after hospital day 7), receipt of an episode of mechanical ventilation longer than 14 days, and onset of Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) after hospital day 7.

Measurements

We collected age at the time of COVID-19 diagnosis, early use of invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV), early use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), early use of vasopressors, gender, race/ethnicity, Charlson Comorbidity Index (12), the month of hospitalization, first measured WBC count, first measured procalcitonin, a community-level indicator of social determinants of health (BU-ShareCare Community Wellbeing Index (13)), region of residence, and center identifier. Additionally, we recorded early major surgeries (defined as a major surgical procedure before hospital day 2) as a proxy for incidental preprocedural testing and early reported traumatic injuries (defined as billed traumatic diagnoses before hospital day 2) as a proxy for incidental admission testing.

Statistical Analysis

For the analysis of EEAU patterns, statistical testing was done with the chi-square test for categorical data and Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous data. Mixed effects logistic regression was used to evaluate predictors of EEAU with random effects for treatment month and center. We conducted a sensitivity analysis by including enteral antibiotics, varying the required number of exposure days from 3 to 5 days, and varying the exposure window from 4 to 7 days. Linear regression on time was used to evaluate temporal trends in our exposure, covariates, and outcomes during the early (from March 2020 to September 2020) and later pandemic periods. To evaluate between center variation, we used analysis of deviance with a chi-square test to compare a model with patient predictors and time to a model with patient predictors, time, and center.

For the analysis of EEAU outcomes, we constructed a 1:1 propensity-matched cohort using the MatchThem package (https://github.com/FarhadPishgar/MatchThem) (14) with nearest-neighbor matching without a caliper on a generalized additive logistic regression model to estimate the propensity for EEAU with a categorical term for month of admission, race, early ECMO use, early mechanical ventilation, early reported traumatic injuries, early major surgery, obesity, and tobacco use as well as a spline term for age and initial WBC count. We considered inclusion of vaccination status and prior immunosuppressive medication use but neither factor was reliably available in the dataset. Covariate balance was assessed using cobalt (15). We used multivariate imputation by chained equations with the MICE package (https://github.com/amices/mice) (16) for imputation of missing age, BMI, and initial WBC count. We assessed the sensitivity to our imputation strategy by also preforming median value imputation and complete case analysis.

A p value of 0.05 was used for statistical significance and the Bonferroni correction was used to adjust for multiple comparisons.

RESULTS

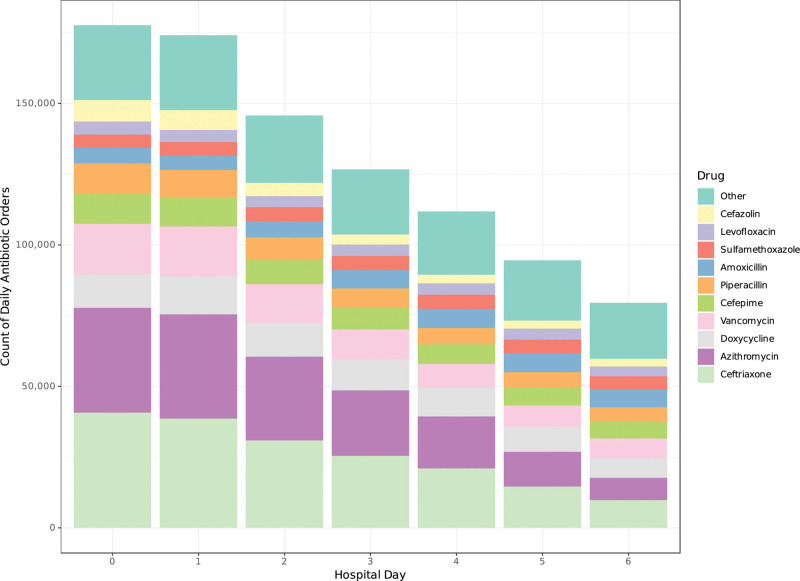

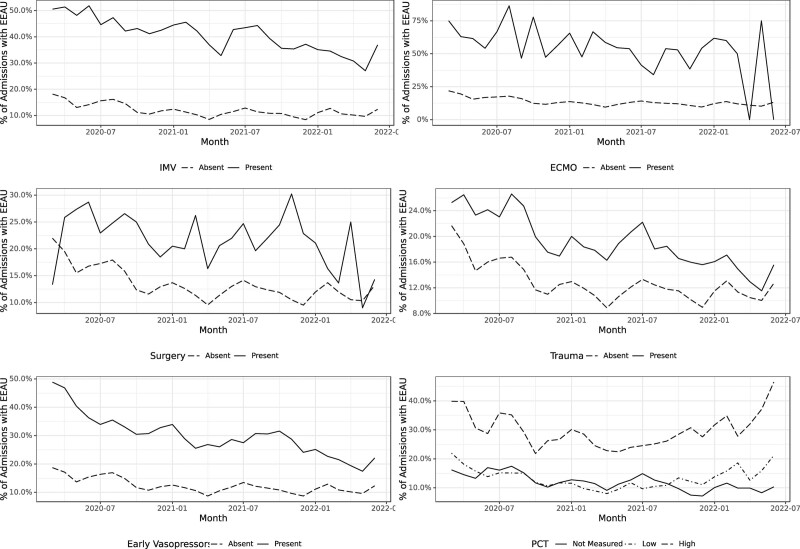

We identified 322,867 qualifying first hospitalizations for analysis, and 43,089 patients received EEAU. Patients who received EEAU were more likely to be older, male, obese, current smokers, and have more comorbid conditions (Table 1). Additional details of the cohort are available in Supplementary Table 1, (http://links.lww.com/CCM/H339). Across all centers, EEAU declined over time from the first month (21.1%) to the last month (13.2%) in the data collection period (p < 0.0001 for trend); however, this trend was not seen after excluding the initial 6 months of data. Average rates of EEAU also varied significantly between centers (deviance explained 7.33% vs 20.0%, p < 0.001) and over time (Fig. 1A). We identified three subsets of centers: a group with consistently low rates, a group with consistently high rates, and a group with varying rates (Fig. 1B). Among nonsurvivors, the median length of stay before mortality was 11 days (IQR 5–19 d). The median duration of initial antibiotic therapy among patients with EEAU was 7 days (IQR 5–14 d). Antibiotic use decreased slightly by day 2 of hospitalization and was significantly reduced by day 5. Ceftriaxone and Azithromycin were the most prescribed antibiotics. Antibiotics with antipseudomonal activity, including cefepime and piperacillin/tazobactam were also prevalent (Fig. 2). The rates of conditions present on admission varied across time periods (Fig. 3): early mechanical ventilation decreased in the early period (p < 0.001 for trend) and then stabilized while early ECMO use did not vary during either period. In contrast, both the rates of early traumatic diagnoses (p < 0.001) and early major procedures (p = 0.004) increased during the later pandemic period. The rate of early vasopressor use decreased during the early pandemic period (p = 0.005) and then decreased during the later pandemic period (p < 0.001). The rates of EEAU across conditions (Fig. 4) also varied across time. The rates of EEAU were stable in the early period and decreased in the later period for patients with early mechanical ventilation (p < 0.001) and early trauma (p < 0.001). The rates of EEAU in patients with early vasopressor use decreased across both the early (p < 0.001) and later (p < 0.001) periods while the rates for EEAU in early major procedures and early ECMO were stable across both time periods. Among patients who had a measured procalcitonin rates of EEAU increased during the later period for both the high (p = 0.001) and low (p = 0.003) groups.

TABLE 1.

Cohort Characteristics and Outcomes

| Characteristic | n | No EEAU, n = 279,778a | EEAU, n = 43,089a | p b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 317,427 | 61 (44, 73) | 64 (50, 75) | < 0.001 |

| Gender | 322,830 | < 0.001 | ||

| Male | 140,501 (50%) | 23,544 (55%) | ||

| Female | 139,250 (50%) | 19,535 (45%) | ||

| Inpatient length of stay | 322,867 | 4 (2, 8) | 8 (5, 16) | < 0.001 |

| Obesity | 322,867 | 141,936 (51%) | 24,860 (58%) | < 0.001 |

| Unknown | 58,018 | 7,506 | ||

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 322,867 | 4 (1, 7) | 6 (3, 9) | <0.001 |

| Days of early antibiotic exposure | 322,867 | < 0.001 | ||

| 0 | 210,263 (75%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| 1 | 32,898 (12%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| 2 | 21,356 (7.6%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| 3 | 15,261 (5.5%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| 4 | 0 (0%) | 11,495 (27%) | ||

| 5 | 0 (0%) | 14,410 (33%) | ||

| 6 | 0 (0%) | 17,184 (40%) | ||

| Current tobacco use | 322,867 | 22,617 (8.1%) | 4,293 (10.0%) | <0.001 |

| Initial WBC count (109/L) | 276,806 | 7.0 (5.1, 9.7) | 8.2 (5.6, 12.2) | < 0.001 |

| Unknown | 42,784 | 3,277 | ||

| Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation on hospital day < 2 | 322,867 | 244 (< 0.1%) | 314 (0.7%) | < 0.001 |

| IMV on hospital day < 2 | 322,867 | 9,514 (3.4%) | 6,920 (16%) | < 0.001 |

| Vasopressor on hospital day < 2 | 322,867 | 14,165 (5.1%) | 6,330 (15%) | < 0.001 |

| In-hospital mortality | 322,867 | 20,424 (7.3%) | 7,401 (17%) | < 0.001 |

| Late antibiotic exposure | 322,867 | 3,299 (1.2%) | 3,601 (8.4%) | < 0.001 |

| Prolonged invasive mechanical ventilation | 322,867 | 2,401 (0.9%) | 1,849 (4.3%) | < 0.001 |

| Late Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea | 322,867 | 2,046 (0.7%) | 760 (1.8%) | < 0.001 |

EEAU = early empiric antibiotic use, IQR = interquartile range.

Statistics presented: median (IQR); n (%).

Statistical tests performed: Wilcoxon rank-sum test; chi-square test of independence.

Properties and outcomes of the cohort stratified by early empiric antibiotic use. Continuous variables are presented as median (IQR) and categorical variables as count (percentage). Missing gender values have been removed to reduce risk of identification.

Figure 1.

A, Absolute rates of early antibiotic usage by month and center. Each circle represents the rate for a center during a given month and the size of the circle is proportional to the number of COVID cases at that center that month. The red line represents the average rate of early antibiotic usage across all centers. B, Monthly rates of early antibiotic usage by center. Each row represents a single center throughout the entire study period. Centers are arranged by overall EEAU rate rank with the highest overall rate centers at the top of the figure. The color represents how that center compared with all other centers during that same month with higher percentiles representing more antibiotic usage (i.e., 75th percentile centers had a higher rate than 75% of all other centers that month). Cells are empty when that center reported no data for that month. EEAU = early empiric antibiotic use.

Figure 2.

Number of antibiotic orders by hospital day. Each order represents a specific drug administered to a single patient during that day. Some centers report concurrent administration of beta-lactam/beta-lactamase inhibitors as two separate medications so beta-lactamase inhibitors are excluded here. A patient on combination antimicrobial therapy would be represented as multiple orders.

Figure 3.

Percentage of total admissions with early usage of ECMO, early usage of IMV, early major surgery, traumatic admission diagnoses, and early usage of vasopressors. ECMO = extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, IMV = invasive mechanical ventilation.

Figure 4.

Rates of admissions with EEAU over time by early usage of ECMO, early usage of IMV, early major surgery, traumatic admission diagnoses, early usage of vasopressors. and procalcitonin status. EEAU = early empiric antibiotic use, ECMO = extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, IMV = invasive mechanical ventilation.

Mechanical ventilation before day 2 (odds ratio [OR] 3.57; 95% CI, 3.42–3.72), ECMO before day 2 (OR 2.14; 95% CI, 1.75–2.61), and early vasopressor use (OR 1.85; 95% CI, 1.78–1.93) but not the region of residence was associated with EEAU after adjustment for treatment month, center, age, gender, traumatic injuries, early major procedures, and Charlson Comorbidity Index. Among patients with procalcitonin measured, procalcitonin greater than 0.5 ng/mL was associated with EEAU (OR 2.81; 95% CI, 2.70–2.92). These results were robust in our sensitivity analyses.

Before propensity matching, there was substantial difference in all important predictors (eFig. 2, http://links.lww.com/CCM/H339). After matching, the largest absolute standardized main difference of all predictors was 0.021, and the balance of all predictors was improved. EEAU was associated with an increased risk for in-hospital mortality (OR 1.27; 95% CI, 1.23–1.33), prolonged mechanical ventilation (OR 1.65; 95% CI, 1.50–1.82), late broad-spectrum antibiotic exposure (OR 3.24; 95% CI, 2.99–3.52), and late CDI (OR 1.60; 95% CI, 1.37–1.87). These results were robust to different imputation strategies and inclusion of enteral antibiotics.

DISCUSSION

This large retrospective cohort study demonstrates that many patients hospitalized with COVID-19 have received EEAU throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, and variation between centers and indications is high. Our observed rates are lower than the previously reported 76% (4), but our cohort is 10 times larger than previous cohorts and includes two years of additional data. While we did not attempt to estimate the rate of bacterial superinfection and the true rate is not known, EEAU in COVID-19 represents a therapy with significant potential harms and uncertain benefits as the vast majority of patients do not have a bacterial infection and cannot benefit from antimicrobial agents. EEAU varies drastically between centers suggesting that clinical equipoise exists around the use of EEAU, but most centers appeared to have similar trends over time. The etiology of these differences could be related to center volumes or may reflect differing antibiotic stewardship practices, incomplete data mappings from the source to the research record, or clinician uncertainty about benefit from EEAU.

EEAU appears to be associated with increased rates of later broad-spectrum antibiotic use, late CDI, prolonged mechanical ventilation, and mortality. Patients were still more likely to die despite receiving EEAU. Although the mechanism linking EEAU to further antibiotic exposure and CDI seems logical, the mechanism linking EEAU to mortality and prolonged mechanical ventilation is less clear. Changes in the lung microbiome have been linked to worse outcomes in critical illness (17). Thus, an intriguing possibility is that increased mortality may in part be due to respiratory tract dysbiosis induced by EEAU. Similarly, critically ill patients who received early antianaerobic antibiotics had less ventilator-associated pneumonia-free days, infection-free days, and overall survival (8). Antianaerobic antimicrobials were common in our study population and may explain the differences in mortality in our cohort, although further research is warranted. Our findings are subject to the limitations of all attempts at causal inference in observational data, namely that residual confounding might bias our estimates of the effect. The harms of unneeded antibiotics are clearly defined in the literature. However, clear guidance on indications of EEAU and rate of secondary bacterial infection is lacking. Classically, Staphylococcus aureus has been identified as a common cause of secondary bacterial infection (18). However, data on the pulmonary microbiome suggests that hyperoxia confers a selective growth advantage for S. aureus over other species that are less oxygen tolerant (19). Distinguishing between dysbiosis and infection when a pathogenic but commensal organism is isolated from respiratory culture in patients with multiple potential causes of severe respiratory failure is beyond the bounds of our current diagnostics. Our work suggests that there may be equipoise regarding EEAU in severe COVID-19 and contributes to the body of literature suggesting harms from antimicrobials in respiratory failure.

One strength of this study includes the size and diversity of the patients and centers represented by the N3C database. There are several important limitations of our study. First, complex data harmonization limited the analyses we were able to perform. For example, vaccination status and prior medication use are both likely to impact the decision to prescribe antibiotics, but neither is available with the reliability needed for our analysis. Second, lack of information regarding the indication for antibiotic use and lack of microbiology testing results in the N3C database limited our ability to exclude patients who may have been prescribed antibiotics for other appropriate infectious conditions. Furthermore, we were unable to identify centers that may have antibiotic stewardship programs that could alter EEAU. Third, we could not evaluate patterns of EEAU among critically ill versus noncritically ill patients because some of the descriptors (such as patient location) are not reported in the N3C database. We attempted to remedy this lack of information by using vasopressors, mechanical ventilation, and ECMO as surrogates for critical illness. Fourth, some risk factors (such as preexisting immunosuppression and vaccination) are not consistently captured in this dataset and could not be included in our analysis without introducing substantial risk of bias. Addition of these variables may alter our estimated effects. Finally, while we suspect that the number of patients who received antibiotics as outpatients before admission was relatively low, formal data regarding antibiotic use before hospital admission is not available in the N3C database. Thus, outpatient antibiotic use before admission could be a potential confounder that affected our outcomes. Our study suggests that clinicians should consider the likelihood of coinfection before initiating antibiotics on admission for patients with COVID-19 and that EEAU may confer harm. Future work should assess the benefits or harms of EEAU in severe COVID-19.

CONCLUSIONS

Although treatment of COVID-19 patients with empiric intravenous antibiotics has declined during the pandemic, the frequency of use remains higher than the reported incidence of bacterial superinfection with significant inter-center variation in antibiotic prescribing practices. These observed usage patterns may be associated with excessive harm and our results are hypothesis-generating. Future research should focus on comparing outcomes and adverse events among COVID-19 patients treated with and without empiric antibiotics.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The work of Dr. Barros was conducted with the support of the Integrated Translational Health Research Institute of Virginia (iTHRIV) Scholars Program. The iTHRIV Scholars Program is supported in part by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award Numbers UL1TR003015 and KL2TR003016 as well as by the University of Virginia (UVA). This content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIH or UVA.

Footnotes

*See also p. 1267.

Drs. Davis, Enfield, Bell, and Barros conceptualized the project. Drs. Loomba, Widere, and Barros analyzed and interpreted the data. Drs. Widere and Barros wrote the initial article draft. All authors revised the article for critical intellectual content and approved the final version of the article.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website (http://journals.lww.com/ccmjournal).

Dr. Loomba’s institution received funding from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; she received support for article research from the National Institutes of Health. The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

N3C Consortium can be found at: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1bOxIzT-IXEfr7RriLI9PgwbuyTbLaTgPXHH2y5Uza70/edit#gid=1399802837.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: Benjamin Amor, Mark M. Bissell, Katie Rebecca Bradwell, Andrew T. Girvin, Amin Manna, Nabeel Qureshi, Christopher G. Chute, Emily R. Pfaff, Davera Gabriel, Stephanie S. Hong, Kristin Kostka, Harold P. Lehmann, Richard A. Moffitt, Michele Morris, Matvey B. Palchuk, Xiaohan Tanner Zhang, Richard L. Zhu, Christopher P. Austin, Kenneth R. Gersing, Samuel Bozzette, Mariam Deacy, Nicole Garbarini, Michael G. Kurilla, Sam G. Michael, Joni L. Rutter, Meredith Temple-O’Connor, Melissa A. Haendel, Tellen D. Bennett, Christopher G. Chute, David A. Eichmann, Justin Guinney, Warren A. Kibbe, Hongfang Liu, Philip R.O. Payne, Emily R. Pfaff, Peter N. Robinson, Joel H. Saltz, Heidi Spratt, Justin Starren, Christine Suver, Adam B. Wilcox, Andrew E. Williams, Chunlei Wu, Emily R. Pfaff, Benjamin Amor, Mark M. Bissell, Marshall Clark, Andrew T. Girvin, Stephanie S. Hong, Kristin Kostka, Adam M. Lee, Robert T. Miller, Michele Morris, Matvey B. Palchuk, Kellie M. Walters, Melissa A. Haendel, Christopher G. Chute, Kenneth R. Gersing, Anita Walden, Anita Walden, Yooree Chae, Connor Cook, Alexandra Dest, Racquel R. Dietz, Thomas Dillon, Patricia A. Francis, Rafael Fuentes, Alexis Graves, Julie A. McMurry, Andrew J. Neumann, Shawn T. O’Neil, Usman Sheikh, Andréa M. Volz, Elizabeth Zampino, Mary Morrison Saltz, Christine Suver, Christopher G. Chute, Melissa A. Haendel, Julie A. McMurry, Andréa M. Volz, Anita Walden, Carolyn Bramante, Jeremy Richard Harper, Wenndy Hernandez, Farrukh M Koraishy, Federico Mariona, Amit Saha, and Satyanarayana Vedula

REFERENCES

- 1.Morens DM, Taubenberger JK, Fauci AS: Predominant role of bacterial pneumonia as a cause of death in pandemic influenza: implications for pandemic influenza preparedness. J Infect Dis. 2008; 198:962–970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ukuhor HO: The interrelationships between antimicrobial resistance, COVID-19, past, and future pandemics. J Infect Public Health. 2021; 14:53–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Langford BJ, So M, Raybardhan S, et al. : Bacterial co-infection and secondary infection in patients with COVID-19: a living rapid review and meta-analysis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020; 26:1622–1629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Langford BJ, So M, Raybardhan S, et al. : Antibiotic prescribing in patients with COVID-19: rapid review and meta-analysis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021; 27:520–531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Teshome BF, Vouri SM, Hampton N, et al. : Duration of exposure to antipseudomonal β-lactam antibiotics in the critically ill and development of new resistance. Pharmacotherapy. 2019; 39:261–270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hensgens MPM, Goorhuis A, Dekkers OM, et al. : Time interval of increased risk for Clostridium difficile infection after exposure to antibiotics. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012; 67:742–748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rhee C, Kadri SS, Dekker JP, et al. ; CDC Prevention Epicenters Program: Prevalence of antibiotic-resistant pathogens in culture-proven sepsis and outcomes associated with inadequate and broad-spectrum empiric antibiotic use. JAMA Netw Open. 2020; 3:e202899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chanderraj R, Baker JM, Kay SG, et al. : In critically ill patients, anti-anaerobic antibiotics increase risk of adverse clinical outcomes. Eur Respir J. 2023; 61:2200910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kullberg RFJ, de Brabander J, Boers LS, et al. : Lung microbiota of critically ill COVID-19 patients are associated with nonresolving acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022; 206:846–856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. ; STROBE Initiative: The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for Reporting Observational Studies. Ann Intern Med. 2007; 147:573–577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haendel MA, Chute CG, Bennett TD, et al. : The National COVID Cohort Collaborative (N3C): Rationale, design, infrastructure, and deployment. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2021; 28:427–443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quan H, Li B, Couris CM, et al. : Updating and validating the Charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol. 2011; 173:676–682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharecare Inc.: Sharecare Community Well-Being Index Methodology. Sharecare. 2021. Available at: https://wellbeingindex.sharecare.com/research/community-well-being-index-methods/. Accessed February 6, 2023

- 14.Pishgar F, Greifer N, Leyrat C, et al. : MatchThem: Matching and weighting after multiple imputation. The R Journal. 2021; 13:228292–228305 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greifer N: cobalt: Covariate Balance Tables and Plots. 2022. Available at: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=cobalt. Accessed November 1, 2022

- 16.Buuren S van, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K: Multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. Journal of Statistical Software. 2011; 45:1–67 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dickson RP, Schultz MJ, van der Poll T, et al. ; Biomarker Analysis in Septic ICU Patients (BASIC) Consortium: Lung microbiota predict clinical outcomes in critically ill patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020; 201:555–563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kalil AC, Thomas PG: Influenza virus-related critical illness: pathophysiology and epidemiology. Crit Care. 2019; 23:258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ashley SL, Sjoding MW, Popova AP, et al. : Lung and gut microbiota are altered by hyperoxia and contribute to oxygen-induced lung injury in mice. Sci Transl Med. 2020; 12:eaau9959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]