Abstract

The effects of various yeast species isolated from raw-milk cheese were evaluated in Beyaz cheese. Four batches of cheeses were produced, in which the control cheese involved only commercial starter culture while YL, DH and KL cheeses were produced with the incorporation of individual Yarrowia lipolytica, Debaryomyces hansenii and Kluyveromyces lactis, respectively. The chemical composition, microbial counts, sensory attributes, volatile compounds and textural properties of cheeses were determined on days 1, 30, and 60 during the ripening period. The results obtained demonstrated that chemical, microbial and sensory properties of cheese varied depending on yeast species. The cheese with Y. lipolytica was the most preferred and it contained more short chain fatty acids, particularly butyric acid. This result could be due to the higher fat content and advanced lipolytic activity. The ripening index of DH was found to be higher than the other cheeses, showing an advanced proteolytic activity in relation to lower hardness in the texture profile. K. lactis was associated with lactose metabolism and promoted the development of Lactococcus spp. The results highlighted a potential use of yeasts as adjunct cultures in Beyaz cheese to develop the sensory properties such as texture and flavor.

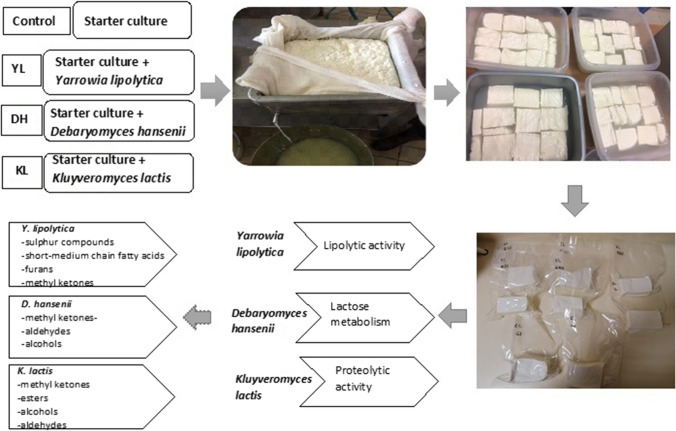

Graphical abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13197-023-05791-3.

Keywords: Yarrowia lipolytica, Debaryomyces hansenii, Kluyveromyces lactis, Yeast, Adjunct, Cheese, Ripening, Flavor

Introduction

The microbiota of many cheeses comprises bacteria, yeast and molds. This microbiota may originate from raw milk in the absence of heat treatment, or may occur naturally at different stages of production (Montel et al. 2014).

The use of raw milk in cheese production requires a more exhaustive sanitary control in order to eliminate pathogens and prevent an adverse health impact. Microbial count and diversity in raw milk is usually decreased to a great extent depending on the applied heat treatment in industrial cheeses. In this way, the usual desired texture and flavor balance of the cheeses is disrupted. Therefore, incorporating microbial cultures into heat-treated milk has become a common technological practice. The aim of this practice is to benefit from the enzymatic activities of microorganisms, exhibiting desired sensory properties and without an adverse effect on human health. The addition of these adjunct cultures in the cheese-making process not only improves the sensory quality but also helps to achieve a rapid ripening of cheese (Settanni and Moschetti 2010). The adjunct cultures may include; non-starter lactic acid bacteria, coryneform bacteria, Micrococcaceae and yeasts or molds (El Soda et al. 2000). Amino acids, organic acids, free fatty acids, and some other volatile substances are formed as a result of proteolytic, lipolytic and glycolytic reactions of the adjunct cultures as well as starter culture to develop desirable cheese flavor.

Yeasts play an important role in cheese ripening such as the formation of alkaline metabolites derived from proteolysis and lipolysis. These events also support bacterial growth and initiate the secondary reactions of ripening (Yalçın et al. 2011). The main yeast species used as adjunct culture in cheeses are; Y. lipolytica, D. hansenii, K. lactis, K. marxianus, and Geotrichum candidum (Kesenkaş and Akbulut 2006). Y. lipolytica supports the sensory properties of cheese with its high extracellular lipolytic and proteolytic activities (Fröhlich Wyder et al. 2019). A low temperature and high salt concentration is reported to have limited effects on the lipolytic activity of Y. lipolytica. This yeast forms precursors for the formation of various aromatic compounds such as ketones, alcohols, fatty acids and esters (Kesenkaş and Akbulut 2006). D. hansenii also contributes to the development of proteolytic and lipolytic reactions. Fatty acids produced from lipolysis are known as precursors in the formation of a wide variety of flavor compounds, such as esters and methyl ketones, which gain a specific flavor in cheeses (Alzobaay and Alzobaay 2018). K. lactis is a common species found in dairy products. Although its main role in dairy products is lactose metabolism, some strains of K. lactis exhibit strong proteolytic and lipolytic activities. These can easily tolerate low pH, low water activity (aw), low storage temperatures and high salt concentration, hence contributing to the formation of aromatic compounds during cheese ripening (De Freitas et al. 2008).

Beyaz cheese (White cheese) is a white-coloured and brined type of Turkish cheese that can be consumed fresh or ripened. Fresh Beyaz cheeses have a soft texture and a very mild flavor, usually dominant with a salty and acidic taste. This cheese is usually ripened for 90 days to obtain a desirable texture, and flavor. However, due to economic reasons in industrial Beyaz cheese production, this period is shortened and it is offered for consumption in less than a month. This causes the cheeses to be presented to the market before reaching the desired flavor and textural properties.

In this study, some yeast isolates obtained from traditional Turkish Divle Cave cheese (Ozturkoglu-Budak et al. 2016a) were evaluated individually as candidate adjunct culture during the production of Beyaz cheese to determine the influence of each strain on the chemical, microbiological, sensory and textural properties of cheeses during ripening. Moreover, the cheeses produced with a yeast as adjunct culture were compared to control cheeses in terms of the ripening duration. For these purposes, specific strains of Y. lipolytica, D. hansenii and K. lactis were individually incorporated during cheese production, in addition to the commercial starter culture. Each batch was evaluated for sensory, textural, microbiological and chemical properties during the ripening period.

Materials and methods

Preparation of yeast strains

Yeast strains deposited in the Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures (CBS, The Netherlands) (Yarrowia lipolytica CBS 13944, Debaryomyces hansenii CBS 13941 and Kluyveromyces lactis CBS 13942) used in this study were previously isolated from Divle Cave cheese made from raw milk and identified molecularly to the species level (Ozturkoglu-Budak et al. 2016a), and evaluated to demonstrate high proteolytic and lipolytic activities (Ozturkoglu-Budak et al. 2016b).

Stock cultures (100 µL) maintained at − 20 °C were grown in 5 mL Malt Extract Broth (MEB) (Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK) and incubated at 28 °C for 3 days. The cell concentrations were determined using a haemocytometer (Weber Scientific, Teddington, UK) and the final concentration of 1 × 106 cells/mL was inoculated into 50 mL reconstituted milk (10%, w/w) which was previously heat-treated at 108 °C for 7 min and incubated under the same conditions for the second propagation step. These final cultures were used individually during cheese production.

Cheese production and sampling

Two cheese batch productions were carried out with a separation interval of 15 days, each with 120 L cows’ milk. During each cheese-making process, the total cheese milk was divided into four portions. Three portions were used in each cheese with each individual activated yeast strain and the last portion for the control cheese.

The raw bovine milk was supplied from the pilot Dairy Plant of Ankara University (Ankara, Turkey) and pasteurized at 72 °C for 30 s. The milk was then cooled to 32 °C and divided into four equal parts into cheese vats. CaCl2 (0.2 g/L) and commercial starter culture consisting of Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis and Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris (Chr. Hansen R-703, Horsholm, Denmark) were added (1%, w/v) into the cheese milk. During the production of cheese batches with yeast adjunct culture, 50 mL reconstituted milk including individual yeast strains with a concentration of 1 × 106 cells/mL were successively added to the cheese milk with the starter culture. The cheeses obtained from all four production batches were coded as; C: Control cheese produced only using starter culture, YL: Yarrowia lipolytica was incorporated in addition to starter culture, DH: Debaryomyces hansenii was incorporated in addition to starter culture, KL: Kluyveromyces lactis was incorporated in addition to starter culture. Liquid rennet (Naturen, Chr Hansen, Horsholm, Denmark; 180 IMCU/ml) was added at a ratio of 1 mL to 10 L of cheese milk and 30 min later, when the pH is 6.39, left to coagulate for 90 min. After the complete coagulation of milk, the coagulum was cut into cubes of about 7 × 7 × 7 cm and rested for about 5–10 min for the removal of the whey. The coagulum was then transferred to cheese cloths and put under pressure (approx. 40 kg weight onto 15 kg curd) at room temperature for 3–4 h until the whey drainage was completed. The obtained curds were divided into blocks weighing between 350–400 g. Twelve cheese blocks were obtained from each batch. The cheese blocks were put into brine (14% NaCl, w/v) for 14–16 h at room temperature, packed into commercial vacuum sealer bags with a composition of Polyethylen/Orevac/Polyamide (44/15/20 µm) via a compact double chamber semi automatic packing machine (MULTIVAC C450, UK) and left to ripen at 4 °C. Different cheese blocks were grated and analyzed in duplicate during the 60 days of ripening on day 1, 30 and 60.

Chemical composition

The cheeses were analysed for pH, titratable acidity (expressed as lactic acid), total nitrogen, water-soluble nitrogen (WSN), total solids (TS), fat and salt contents according to the methods described by Ozturkoglu-Budak et al. (2016c). A pH-meter electrode (MP 225 Mettler Toledo, Columbus, OH) was directly inserted into the slurry cheese samples (10 g cheese and 10 ml distilled water) to measure the pH. Titratable acidity was measured via titration with 0.1 N NaOH (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). Total solid was analyzed with gravimetric method at 103 °C. Salt content was determined by titration with AgNO3 (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). Gerber-Van Gulik method was used to measure the fat content. Kjeldahl method was used to find the total nitrogen and water-soluble nitrogen contents. Ripening index (RI) indicates the progress of maturation and represents the degree of proteolysis (McSweeney and Fox 1997). RI values were calculated from the ratio of WSN content to total nitrogen content [RI = (WSN/TN) × 100].

Microbial counts

Total aerobic mesophilic bacteria (TAMB), Lactobacillus spp., and Lactococcus spp. were counted using the pour plate technique whereas yeast and mold counts were determined according to the spread plate technique (Harrigan and McCance 1976). Grated cheese (10 g) was homogenised with 90 mL Ringer solution (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) in a peristaltic blender (Bag Mixer 400 VW; Interscience, Saint-Nom-La-Breteche, France) for 2 min and tenfold dilutions were plated in duplicate on specified mediums for each microbial group. TAMB were grown on the plate count agar (Merck) at 35 °C for 48 h. Yeasts and molds was determined on malt extract agar (Merck) with 10% tartaric acid after incubation at 28 °C for 5–7 days. Lactobacilli were counted on de Man-Rogosa-Sharpe Agar (MRS, Merck) that adjusted to pH 5.7, after an anaerobic incubation at 37 °C for 72 h. Lactococci were grown on M17 agar (Merck) after an aerobic incubation at 30 °C for 24–48 h. The results were calculated as log10 CFU/g cheese.

Sensory analysis

The sensory properties of cheeses on days 1, 30 and 60 of ripening were evaluated by seven trained panelists from the Department of Dairy Technology (Ankara University) who were familiar with the sensory characteristics of Beyaz cheese according to the method used by Clark and Costello (2009). The sensory evaluation characteristics included flavor, texture and appearance. All the sensory attributes were graded on a ten-point hedonic scale (1: poor/unacceptable, 10: excellent/very much liked).

Texture profile analysis

Textural properties were determined using a TA.XT Plus Texture analyser (Stable Micro Systems, Surrey, UK) as described by Bourne (2002). Cheeses were cut into 10 mm cubes and a 20 mm diameter aluminium cylindrical probe (SMP/20) and a 30 kg force load cell were used. The probe was moved at a speed rate of 5 mm/s from the cheese surface for a distance of 5 mm with a trigger force of 5 g.

Volatile compound analysis

Volatile profile analyses were performed according to the method described by Ozturkoglu-Budak et al. (2016c). The head-space solid phase micro extraction (HS-SPME) technique was used for the extraction of volatile compounds on gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC–MS) (7890A/5975C Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) equipped with DB-WAX column (30 m × 0.32 mm × 0.25 µm; i.d. Agilent Technologies). Extraction of volatile compounds was performed using 75 μm of carboxen/polydimethylsiloxane solid-phase microextraction (SPME) fiber (Supelco, Bellefonte, PA, USA) via continuously stirred with a magnetic stir bar for 30 min at 45 °C. During analyses, helium was used as carrier gas at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The initial temperature program of GC/MS was isothermal at 40 °C for 10 min, followed by elevation of the temperature to 110 °C at a rate of 5 °C/min and 240 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min with a final extension of 5 min at 250 °C. Mass spectra were recovered in the electron impact mode at an ionization voltage of 70 eV, and data were collected at a rate of 3.2 scans/s over a range of m/z 35–500.

Identification of volatile compounds was performed by comparing the retention indices and mass spectra of separated compounds with n-alkane (C4–C20) reference standards by using the libraries of Wiley 7, NIST0.5 and Flavor on Agilent MSD software (Agilent MSD Chemstation, Santa Clara, CA). The relative amount of each volatile compound was calculated based on the ratio of peak areas of unknown compound and the internal standard (2 methyl-3 heptanone and 2-methylpentanoic acid, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) that was used.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were carried out using Minitab package program (version Minitab ®16.1.1, Minitab Inc., State College, PA, USA). Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to determine the statistical differences among the cheese batches and ripening times. Subsequently, Tukey’s Multiple Range Test was conducted to determine statistically significant differences. Significant differences were reported at P < 0.05.

Results and discussion

Chemical composition and pH of Beyaz cheeses

The chemical properties of Beyaz cheeses produced with individual yeasts as adjunct culture during the ripening period are shown in Table 1. Different cheese batches and ripening time had significant effects on pH and titratable acidity values (P < 0.05).

Table 1.

Chemical properties of Beyaz cheeses during 60 days of ripening

| Day | C | YL | DH | KL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH value | 1 | 4.99 ± 0.040DEF | 5.23 ± 0.015BC | 5.19 ± 0.115BCD | 5.18 ± 0.010CD |

| 30 | 4.88 ± 0.020EF | 5.28 ± 0.020BC | 5.10 ± 0.010CDE | 5.31 ± 0.020BC | |

| 60 | 4.82 ± 0.010F | 5.41 ± 0.040AB | 5.20 ± 0.020BCD | 5.59 ± 0.035A | |

| Titratable acidity (%) | 1 | 1.01 ± 0.023EF | 1.29 ± 0.035D | 1.72 ± 0.005BC | 1.89 ± 0.040B |

| 30 | 1.56 ± 0.030C | 1.84 ± 0.068B | 2.14 ± 0.020A | 2.23 ± 0.020A | |

| 60 | 1.90 ± 0.020B | 0.90 ± 0.045F | 1.35 ± 0.055D | 1.20 ± 0.010DE | |

| Total solids (%) | 1 | 42.65 ± 0.150Ab | 43.05 ± 0.180B | 43.58 ± 0.630B | 44.93 ± 0.535B |

| 30 | 44.04 ± 0.160a | 45.50 ± 0.595 | 43.78 ± 0.115 | 45.62 ± 1.095 | |

| 60 | 45.14 ± 0.265a | 44.68 ± 0.330 | 44.77 ± 0.240 | 44.04 ± 0.175 | |

| Fat in total solids (%) | 1 | 43.37 ± 1.020Aab | 44.14 ± 0.185A | 39.02 ± 0.565B | 38.94 ± 0.650B |

| 30 | 44.71 ± 0.530a | 45.08 ± 1.690 | 39.97 ± 1.040 | 39.68 ± 0.140 | |

| 60 | 42.62 ± 0.395b | 46.15 ± 0.315 | 38.11 ± 0.620 | 36.71 ± 0.125 | |

| Salt (%) | 1 | 3.01 ± 0.108E | 3.24 ± 0.043D | 3.36 ± 0.029CD | 3.56 ± 0.029BC |

| 30 | 3.26 ± 0.069D | 3.50 ± 0.039CD | 3.49 ± 0.064BC | 3.69 ± 0.031AB | |

| 60 | 3.59 ± 0.022BC | 3.54 ± 0.058BC | 3.65 ± 0.044AB | 3.70 ± 0.026A | |

| Total protein (%) | 1 | 15.22 ± 0.530AB | 14.35 ± 0.120B | 14.76 ± 0.140AB | 15.09 ± 0.025A |

| 30 | 14.88 ± 0.355 | 14.54 ± 0.115 | 15.02 ± 0.130 | 15.31 ± 0.065 | |

| 60 | 14.76 ± 0.700 | 14.67 ± 0.015 | 15.20 ± 0.100 | 15.65 ± 0.170 | |

| Water-soluble-nitrogen (%) | 1 | 1.65 ± 0.075G | 4.60 ± 0.025E | 5.65 ± 0.025B | 5.06 ± 0.010CD |

| 30 | 1.86 ± 0.050G | 4.68 ± 0.060E | 5.70 ± 0.005B | 5.20 ± 0.030C | |

| 60 | 2.70 ± 0.115F | 4.845 ± 0.045DE | 6.37 ± 0.030A | 5.51 ± 0.030B | |

| Ripening index (%) | 1 | 10.77 ± 0.085H | 32.02 ± 0.440E | 38.20 ± 0.195B | 33.54 ± 0.120DE |

| 30 | 12.50 ± 0.040G | 32.20 ± 0.375E | 37.92 ± 0.295B | 33.98 ± 0.340CD | |

| 60 | 18.21 ± 0.030F | 33.04 ± 0.275DE | 41.91 ± 0.075A | 35.22 ± 0.575C |

C: Control cheese, YL: Cheese made with Yarrowia lipolytica, DH: made with Debaryomyces hansenii, KL: Cheese made with Kluyveromyces lactis. Different lowercase letters within the same column indicate significant differences during ripening (p < 0.05). Differences in values with detected interactions are shown with capital letters (P < 0.05)

The pH values of the control cheese decreased during ripening, as was expected for Beyaz cheese (Hayaloglu et al. 2005). However, an increase was observed in the pH of the cheeses produced with yeast species. The reason for this can be justified by the assimilation of lactic acid by the incorporated yeast and formation of alkali proteolysis products. In general, yeasts initiate the second half of ripening by increasing pH (Kesenkaş and Akbulut 2006). These events cause changes in pH and acidity as a result of reactions performed via the extracellular lipase and protease enzymes. In particular, alkali protein breakdown products are formed as a result of the hydrolysis of the protein matrix in cheese (Sousa et al. 2001). These alkaline metabolic products cause a pH increase during cheese ripening (Yalçın et al. 2011).

A higher titratable acidity was observed in the batches produced with yeast strains during the first 60 days of ripening. This could be due to the competition of yeast with lactic acid bacteria for the available carbohydrates in the medium, which are more efficient in the formation of lactic acid (Yalçın et al. 2011). The highest increase was observed in the KL cheese produced with K. lactis and the least increase was detected in control cheese. This could be due to the fact that K. lactis is capable of fermenting lactose to form lactic acid. The observed decrease in lactic acid (%) of the cheeses produced with yeast strains after 30 days of ripening can be explained by the conversion of lactic acid to other aromatic substances such as ketones, alcohols, lactones, esters, aldehydes by the incorporated yeast species during secondary biochemical events (McSweeney 2004). Notwithstanding, the control cheese showed an increase in titratable acidity until the end of the ripening due to the ongoing starter activity as well as the effect of pH value, salt content and lactose concentration of cheese prior to ripening.

There was no correlation between cheeses and ripening days in terms of both total solids (TS) and fat contents (P ≥ 0.05). The reason for this was thought that water evaporation was minimized as the cheeses were ripened in packages. TS values of all cheese samples increased during the first 30 days of ripening, but tended to decrease again towards the end of ripening, except for control cheese. A higher rate of syneresis as a result of increased contraction in the clot due to a higher acidity caused by yeast activity could be the reason for this increase in the first 30 day of ripening. The ongoing salt transfer to cheese matrix and water loss from the structure during ripening could also be among the other reasons.

The YL cheeses compared to other cheeses showed an increase in fat content (%) as ripening progressed. Y. lipolytica is reported to have the ability to increase and accumulate lipid concentration up to 50% of the cell dry mass from wastes such as rice bran hydrolysate and by-products of the agro-industrial sector (Tsigie et al. 2012).

Water soluble nitrogen (WSN) and ripening index (RI) values were significantly influenced by different cheese batches (P < 0.05). It is stated that secondary microorganisms mostly cause proteolysis during storage and therefore affect nitrogen content. The RI value of the control cheese was found to be significantly lower than the cheeses produced with yeast incorporation. Similarly, Upadhyay et al. (2004) reported that an increase in RI during ripening was caused by proteolytic enzymes synthesized by microorganisms such as starter and non-starter lactic acid bacteria (LAB), yeasts and molds.

Viability of microbial groups

TAMB, yeasts and molds, Lactobacillus spp. and Lactococcus spp. counts for each cheese during the 60 days of ripening period are presented in Table 2. TAMB population of the control cheese produced using only commercial starter culture increased from 7.97 log10 CFU/g to 8.10 log10 CFU/g until the 30th day of ripening. A decrease in the population of TAMB was detected during the ripening periods of cheeses made with yeast species. Some yeasts like K. lactis stimulate the growth of lactic acid bacteria and therefore of total mesophilic microorganisms.

Table 2.

Microbial counts (log10 CFU/g)of Beyaz cheeses during 60 days of ripening

| Day | C | YL | DH | KL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total aerobic mesophilic bacteria | 1 | 7.97 ± 0.105AB | 8.30 ± 0.190A | 7.83 ± 0.125ABC | 8.45 ± 0.405A |

| 30 | 8.10 ± 0.175A | 7.71 ± 0.245ABC | 7.02 ± 0.105BCD | 7.74 ± 0.065ABC | |

| 60 | 6.84 ± 0.070CD | 6.63 ± 0.115D | 5.20 ± 0.085E | 5.41 ± 0.170E | |

| Yeasts and molds | 1 | ˂1Bb | 4.47 ± 0.245A | 5.07 ± 0.115A | 4.66 ± 0.520A |

| 30 | ˂1b | 4.88 ± 0.065 | 4.96 ± 0.275 | 4.81 ± 0.265 | |

| 60 | 1.20 ± 0.000a | 3.38 ± 0.025 | 3.89 ± 0.205 | 3.76 ± 0.515 | |

| Lactobacillus spp. | 1 | 8.20 ± 0.070b | 7.72 ± 0.510 | 7.63 ± 0.330 | 7.85 ± 0.355 |

| 30 | 8.46 ± 0.035ab | 7.84 ± 0.410 | 7.79 ± 0.350 | 7.58 ± 0.740 | |

| 60 | 8.92 ± 0.075a | 8.77 ± 0.040 | 8.36 ± 0.305 | 8.30 ± 0.620 | |

| Lactococcus spp. | 1 | 8.22 ± 0.140ABCD | 8.34 ± 0.020ABCD | 7.21 ± 0.110BCD | 8.15 ± 0.110ABCD |

| 30 | 8.62 ± 0.390ABC | 7.11 ± 0.035CD | 8.77 ± 0.430AB | 8.50 ± 0.545ABC | |

| 60 | 8.90 ± 0.280A | 6.88 ± 0.060D | 8.74 ± 0.375AB | 9.09 ± 0.195A |

C: Control cheese, YL: Cheese made with Yarrowia lipolytica, DH: made with Debaryomyces hansenii, KL: Cheese made with Kluyveromyces lactis. Different lowercase letters within the same column indicate significant differences during ripening (p < 0.05). Differences in values with detected interactions are shown with capital letters (P < 0.05)

Although yeast and mold population were not detected in the cheese until day 60, the highest count was determined in DH during the whole ripening period. The reason for this situation can be interpreted as D. hansenii being mesophilic as well as more resistant in cheese production and ripening conditions due to its tolerance to high salt concentration and low water activity (Alzobaay and Alzobaay 2018). Besides, a higher yeast-mold count detected at the beginning of the ripening period showed a decreasing trend towards the end in each cheese. In a study performed by Alzobaay (2018), a decrease in the count of D. hansenii was observed during the 56-day ripening period of Monterey cheese. The reason for this might be due to the increase in the total solid content of cheese which may reduce the effectiveness of the yeast.

In terms of lactobacilli population, the difference among the ripening days was found to be significant (P < 0.05). This microbial group showed an increasing trend during ripening. Throughout the whole ripening period, the highest lactobacilli count was detected in the control cheese, whereas similar values were observed in the other cheeses made with yeast species (P ˃ 0.05). The highest count of lactococci during ripening was found in the KL cheese, ranging from 8.15 log10 CFU/g to 9.09 log10 CFU/g. Kluyveromyces lactis favors the growth of lactic acid bacteria through the release of growth factors, such as amino acids and vitamins. The more acidic environment caused by K. lactis can promote the survival and development of Lactococcus spp. (Belloch et al. 2011). Since Y. lipolytica and D. hansenii are mostly responsible for lipolytic and proteolytic activities in cheese (Yalçın et al. 2011), antimicrobial metabolites and other products formed during these reactions might have an inhibitory effect on Lactococcus spp. in the cheeses of YL and DH.

Sensory evaluation

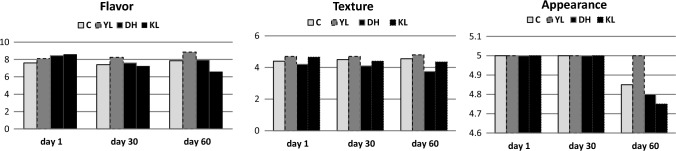

The sensory attributes of cheeses are given in Fig. 1. Different cheese batches and ripening time had significant effects on flavor and texture attributes (P < 0.05). With regard to flavor, YL was the most admired one among all the cheeses. When compared to the control cheese, YL and DH cheeses were more liked, while the KL cheese was not preferred. YL cheese was the most appreciated cheese probably due to the number and type of flavor compounds such as butyric acid and diacetyl as a result of lipolysis. In contrast, the flavor of the KL cheese was found higher during the first 30 days whereas a significant decrease was observed from the second month of ripening. This situation might be caused by the formation of metabolites or flavor compounds as a result of the secondary biochemical reactions of K. lactis, and also the negative effect of these compounds on the flavor as well as the reactions performed by proteolytic, lipolytic and glycolytic enzymes (Leclercq-Perlat et al. 2004). The levels of proteolysis, lipolysis or glycolysis, and the balance among them cause variable sensory attributes via their flavour forming pathways (Tekin and Hayaloglu 2023).

Fig. 1.

Sensory attributes of Beyaz cheeses during ripening (C: Control cheese, YL: Cheese made with Yarrowia lipolytica, DH: Cheese made with Debaryomyces hansenii, KL: Cheese made with Kluyveromyces lactis)

In terms of texture, YL cheese received a very high point and DH cheese received the lowest point. DH and KL cheeses got lower points in terms of texture, probably due to the softening of the cheeses during ripening. Despite the softening in the texture, a high flavor appreciation indicates the formation of desired flavor compounds in cheese matrix. Consistent with the obtained results, Alzobaay and Alzobaay (2018) showed that cheese produced with D. hansenii as an adjunct culture received more appreciation at the end of the ripening period compared to the control cheese.

Instrumental texture profile

The texture profile properties of cheeses during ripening is given in Table 3. Different cheese batches and ripening time had significant effects on hardness values (P < 0.05). The hardest cheese was YL, whereas hardness of DH and KL cheeses were lower than the control cheese. This can be explained by the developed proteolysis in the DH and KL cheeses had weakened the texture and therefore showed lower hardness values than C because Y. lipolytica characterizes with higher lipolytic activity rather than proteolytic activity. Similarly, D. hansenii and K. lactis were reported having high protease activity (Agarbati et al. 2021). This is thought to be the reason why the hardness of the YL cheese was found to be significantly higher (P ˂ 0.05) than the DH and KL cheeses in which proteolysis was dominant.

Table 3.

Texture profile of Beyaz cheeses during 60 day of ripening

| Day | C | YL | DH | KL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hardness (g) | 1 | 1125.31 ± 52.232ABC | 1224.48 ± 69.910AB | 1227.92 ± 27.548AB | 1308.44 ± 56.185A |

| 30 | 1054.55 ± 24.036BCD | 1058.28 ± 37. 900BCD | 849.24 ± 13.640DE | 659.78 ± 70.924E | |

| 60 | 973.38 ± 23.553CD | 994.11 ± 24.116BCD | 661.08 ± 23.192E | 910.62 ± 23.233CD | |

| Adhesiveness (g s) | 1 | − 2.07 ± 0.251 | − 2.33 ± 0.581 | − 0.09 ± 2.306 | − 2.49 ± 0.006 |

| 30 | − 3.34 ± 0.194 | − 2.98 ± 0.983 | − 2.07 ± 0.013 | − 0.04 ± 3.068 | |

| 60 | − 4.43 ± 0.081 | − 3.70 ± 0.189 | − 1.76 ± 0.003 | − 4.64 ± 0.066 | |

| Springiness (cm) | 1 | 0.92 ± 0.003B | 0.92 ± 0.004B | 0.93 ± 0.001B | 0.93 ± 0.002B |

| 30 | 1.01 ± 0.010B | 1.02 ± 0.034B | 1.06 ± 0.944A | 1.00 ± 0.009B | |

| 60 | 1.03 ± 0.042B | 1.06 ± 0.063B | 1.31 ± 0.004B | 1.16 ± 0.057B | |

| Gumminess (g) | 1 | 1007.61 ± 64.883ABC | 1194.57 ± 64.243A | 820.18 ± 21.795CDEF | 1089.67 ± 37.627AB |

| 30 | 993.48 ± 61.288ABCD | 769.26 ± 46.488DEF | 709.30 ± 31.898EFG | 846.78 ± 6.995CDEF | |

| 60 | 663.57 ± 27.369FG | 711.47 ± 3.813EFG | 489.18 ± 26.021G | 923.49 ± 26.756BCDE | |

| Chewiness (g cm) | 1 | 1947.10 ± 8.890D | 2005.68 ± 29.521D | 1691.07 ± 51.647D | 1827.05 ± 3.808D |

| 30 | 2535.22 ± 33.502BCD | 1522.67 ± 682.888D | 2422.04 ± 113.028CD | 2465.63 ± 46.285CD | |

| 60 | 2681.32 ± 51.360ABCD | 3811.22 ± 95.542A | 3703.24 ± 242.348AB | 3500.26 ± 29.491ABC |

C: Control cheese, YL: Cheese made with Yarrowia lipolytica, DH: made with Debaryomyces hansenii, KL: Cheese made with Kluyveromyces lactis. Different lowercase letters within the same column indicate significant differences during ripening (p < 0.05). Differences in values with detected interactions are shown with capital letters (P < 0.05)

During the ripening of cheeses, an increase in springiness is observed probably due to the residual coagulant and protein degradation. Proteolysis development is a factor leading to high springiness, by relaxing protein chains or causing a weak protein network with a low molecular weight peptide formation (Pena-Serna et al. 2016). In rennet-curd cheeses residual chymosin is responsible for αs1-casein hydrolysis and formation of αs1-I peptide during primary proteolysis, with a consequent softening of the cheese paste. Moisture loss may also affect this result. According to our data, DH and KL cheeses had highest springiness, respectively, confirming the effect of proteolysis level obtained by ripening index values on springiness.

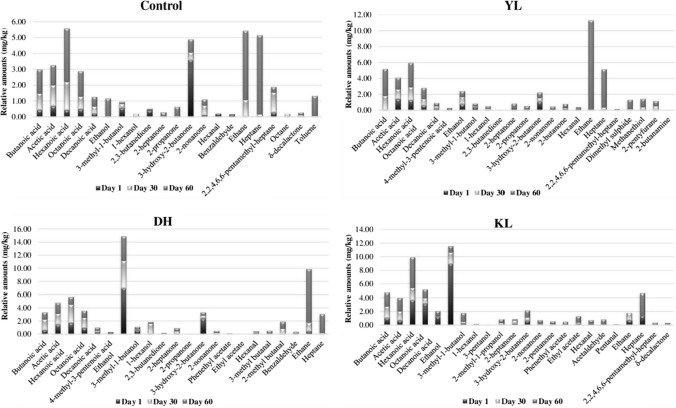

Volatile compound profiles

Carboxylic acids

The highest amount of butyric acid detected in the YL cheese can be interpreted as Y. lipolytica promoted lipolysis. Moreover, acetic acid was most frequently determined in the KL and DH cheeses. This implies that K. lactis and D. hansenii are the microorganisms responsible for lactose metabolism. The fact that carboxylic acids show an increasing trend during ripening confirms that these formations are supported by microbial activity. Since the YL was the most preferred cheese in terms of flavor during sensory analysis, it can be said that sufficient concentration of butyric acid has an effect on desired flavor formation in this cheese.

Other short and medium chain fatty acids such as caproic (hexanoic) and caprylic (octanoic) are also a result of lipolysis. The presence of these acids showed an increasing trend during ripening (Fig. 2; Supplemental Table S1). In terms of capric acid, KL cheese had a higher concentration than all the other cheeses (P < 0.05). There was no significant difference in the amount of decanoic (capric) acid during ripening (P ≥ 0.05). Therefore, it is thought that this fatty acid formation is independent of microbial activity and might be milk-derived or comes from lipolysis. 4-Methyl-3-pentenoic acid, a branched-chain fatty acid, was detected in small amounts at the beginning, but was not detected in any of the cheeses at the end of ripening.

Fig. 2.

Variation of the main volatile compounds of Beyaz cheeses during ripening (C: Control cheese, YL: Cheese made with Yarrowia lipolytica, DH: Cheese made with Debaryomyces hansenii, KL: Cheese made with Kluyveromyces lactis)

Alcohols

Within the scope of our study, ethanol, 3-methylbutanol (isoamyl alcohol) and 1-hexanol were detected during the whole ripening period in all the cheeses, whereas other alcohols shown in Fig. 2 were detected in trace amounts in some cheeses at different time intervals (Supplemental Table S1).

Ethanol was the main alcohol in all cheese samples. Its formation was mostly observed in the KL and DH cheeses at the beginning of ripening but it showed a decreasing trend during ripening. The reason for this decrease is due to reaction with acids to form esters (Zhang et al. 2021). The highest ethanol formation at the end of ripening was determined in the DH cheeses (P < 0.05).

3-Methylbutanol, a branched-chain alcohol (as well as a primary alcohol) was more dominant in the KL cheeses (P < 0.05) demonstrating that K. lactis promotes this formation. Furthermore, Curioni and Bosset (2002) reported that primary alcohols are formed as a result of lactose metabolism. It has also been reported that 3-methylbutanol, has a low detection threshold and therefore has an important role in the cheese flavor development (Carbonell et al. 2002). Similarly, Atanassova et al. (2016), stated that D. hansenii and K. lactis are the main alcohol-producing yeasts in cheese.

Ketones

Ketones are reported to be in high concentrations, particularly in cheeses made with yeast or mold adjuncts, and can be reduced to secondary alcohols as intermediate compounds. Advanced enzyme systems of yeast and molds are effective for ketone formation. Ketones have a specific contribution to cheese flavor with a low detection threshold and sour odor (Curioni and Bosset 2002). This study confirms that ketone formation is promoted by the presence of yeasts, as they are detected with greater variety and higher amounts in cheeses made with yeast strains compared to the control cheese.

However, fluctuations were observed in detected ketone compounds as some were increased with ripening and some others decreased. Although 2,3-butanedione and 3-hydroxy-2-butanone decreased with ripening, methyl ketones such as 2-heptanone and 2-nonanone showed an increasing trend in all the batches except for the KL cheeses Similarly, the concentration of methyl ketones, which increased during ripening, except for KL cheeses, are formed as a result of the conversion of free fatty acids during lipolysis via yeast species. 2-Heptanone and 2-butanone were detected most in the YL cheese, whereas 2-pentanone was only detected in the KL cheese. 2 Butanone can be formed by two pathways: from lactose via microorganisms or from 2,3 butanedione via citrate metabolism (Sousa et al. 2001). Yeasts such as Y. lipolytica or K. lactis are known for their production of methyl ketones. In a similar study, the incorporation of Y. lipolytica on the cheese surface was associated with the formation of short chain ketones (Sorensen et al. 2011). Another study, examined the effect of using Y. lipolytica and K. lactis in blue cheese as adjunct cultures demonstrated that Y. lipolytica can increase ketone production by promoting ripening and K. lactis can inhibit the formation of ketones produced by P. roqueforti (Price et al. 2014).

Esters

In this study, two ester compounds, ethyl acetate and phenethyl acetate, were detected in cheeses. These compounds either form at the end of ripening (60th day) or the amount increases during this period. The increased formation of esters might be associated with a decrease in the amount of some alcohols at the end of ripening due to acid and alcohol esterification (Delgado et al. 2010). Ethyl acetate determined in the KL cheeses in an increasing rate during ripening is thought to be formed by esterification of acetic acid with ethanol (Curioni and Bosset 2002). Phenethyl acetate was not detected during the whole ripening period in the KL and YL cheeses, but was detected at the end of ripening in the DH and KL cheeses. K. lactis is a yeast characterized by great ability to form esters, different to other yeasts.

Aldehydes

Since the detection threshold values are low, aldehydes are effective in cheese aroma (Curioni and Bosset 2002). In addition, low amounts of aldehydes are reported as a desirable indicator in cheese ripening, whereas high concentrations cause undesirable flavor formation (Moio and Addeo 1998). In this study, fluctuations in the aldehyde concentrations were observed as it is expected during ripening and/or storage of fermented products (Moio and Addeo 1998). Among the detected aldehyde compounds, 2-methyl butanal, 3-methyl butanal and benzaldehyde can be related with D. hansenii (Zhang et al. 2021), and acetaldehyde with K. lactis. Hexanal also detected in all cheeses showing fluctuations during ripening, but it was highest in the KL cheeses at the end of the ripening period (P ˂ 0.05).

Hydrocarbons and miscellaneous compounds

In this study, ethane and heptane were found in all cheeses and showed an increasing trend during ripening. Ethane was found mostly in the YL cheeses (P ˂ 0.05). As for heptane, since it was determined at the highest level in the control cheese, its formation is thought to be independent of the incorporated yeast species.

Dimethyl disulfide and methanethiol from sulfur compounds and 2-pentylfuran from furans showed an increasing trend in the ripening stage of the YL cheeses. These compounds are estimated to have an effect on the YL cheese that is mostly appreciated in terms of flavor. Atanassova et al. (2016), stated that D. hansenii is the main yeast species responsible for the production of sulfur compounds in pasteurized whole milk in terms of producing sulfury, cheesy, rancid and alcoholic notes among the other species like Y. lipolytica, K. lactis, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Pichia spp., Candida spp.

Conclusion

In recent years, the dairy industry, aims to produce novel products in order to meet consumer expectations such as consuming nutritious, delicious and health-related products as well as to compete with other companies. Use of commercial cultures in industrial cheeses, provide a standardized product but a uniform taste and flavor. Besides, consumers require diversity in sensory properties other than the specific salt and acid taste that Beyaz cheese provides. Yeast adjunct culture are known for their enzymatic activity as well as their promoting lactic starter culture activity. Therefore, yeasts could be technologically integrated into Beyaz cheese production as an adjunct culture to enhance flavour development during ripening in a relatively shorter period.

In this study, YL cheeses exhibited higher concentrations of sulfur compounds (methanethiol, dimethyl disulfide), short-chain fatty acids such as butyric acid, furans and short-chain ketones (2-butanone, 2-propanone) whereas DH cheeses had higher alcohols (1-propanol, 2 methyl butanol) aldehydes (2-methyl butanal, 3-methyl butanal) and ketones (2 pentanone, 2 heptanone). Furthermore, KL cheeses had higher ratios of esters (ethyl acetate, 2-methyl propyl acetate, 3-methyl butyl acetate), methyl ketones such as 2-pentanone, 2-heptanone, 2-nonanone), alcohols (ethanol, 2 -methyl propanol, 3-methyl butanol) and aldehydes (acetaldehyde, 2-methyl butanal, 3-methyl butanal). In conclusion, use of different yeast adjunct culture had found variable effects in Beyaz cheese properties including physicochemical, microbial, textural and sensory. In terms of sensory properties, YL and DH cheeses were the most appreciated cheeses in terms of flavor, respectively, at the end of ripening. However, as to texture profile DH cheese determined as the softest cheese. A ripening period of 60 days was found to be a bit long for DH and KL cheeses due to the observed softening, whereas this period was determined to be enough for the development of the desirable flavor in YL cheeses.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

BS-D: formal analysis, Writing–original draft, contributed to the design and analysis of the research, SO-B: formal analysis, Writing–original draft, contributed to the design and analysis of the research, and also to the writing of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public or commercial sectors.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest

The author declares there is no conflicts to declare.

Ethics approval

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Agarbati A, Marini E, Galli E, Canonico L, Ciani M, Comitini F. Characterization of wild yeasts isolated from artisan dairies in the Marche region, Italy, for selection of promising functional starters. LWT. 2021;139:110531. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2020.110531. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alzobaay A, Alzobaay W. Role of Debaryomyces hansenii yeast in improving the microbial and sensory properties of monterey cheese. AJVS. 2018;11(1):8–14. doi: 10.37940/AJVS.2018.11.1.2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Atanassova MR, Fernandez-Otero C, Rodriguez-Alonso P, Fernandez IC, Garabal JI, Centeno JA. Characterization of yeasts isolated from artisanal short-ripened cows cheeses produced in Galicia (NW Spain) Food Microbiol. 2016;53:172–181. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2015.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belloch C, Querol A, Barrio E. Yeasts and Molds: Kluyveromyces spp Encyclopedia of Dairy Sciences. London: Elsevier; 2011. pp. 754–76.. [Google Scholar]

- Bourne M. Food texture and viscosity: Concept and measurement. 2. London: Academic Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Carbonell M, Nunez M, Fernandez-Garcia E. Evolution of the volatile components of ewe raw milk La Serena cheese during ripening. Correl Flavour Charact Le Lait. 2002;82:683–698. [Google Scholar]

- Clark S, Costello M. Dairy products evaluation competitions. In: Clark S, Costello M, Drake M, Bodyfelt F, editors. The sensory evaluation of dairy products. New York: Springer; 2009. pp. 43–71. [Google Scholar]

- Curioni PMG, Bosset JO. Key odorants in various cheese types as determined by gas chromatography-olfactometry. Int Dairy J. 2002;12(12):959–984. doi: 10.1016/S0958-6946(02)00124-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Freitas I, Pinon N, Berdague JL, Tournayre P, Lortal S, Thierry A. Kluyveromyces lactis but not Pichia fermentans used as adjunct culture modifies the olfactory profiles of cantalet cheese. J Dairy Sci. 2008;91(2):531–543. doi: 10.3168/jds.2007-0136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado FJ, González-Crespo J, Cava R, García-Parra J, Ramírez R. Characterisation by SPME–GC–MS of the volatile profile of a Spanish soft cheese P.D.O. Torta del Casar during ripening. Food Chem. 2010;118(1):182–189. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.04.081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- El Soda M, Madkor A, Tong S. Adjunct cultures: Recent developments and potential significance to the cheese industry. J Dairy Sci. 2000;83:609–619. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(00)74920-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Fröhlich Wyder MT, Arias-Roth E, Jakob E. Cheese yeasts. Yeast. 2019;36(3):129–141. doi: 10.1002/yea.3368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrigan WF, McCance ME. Laboratory methods in food and dairy microbiology. London: Gulf professional publishing; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Hayaloglu AA, Guven M, Fox PF, McSweeney PLH. Influence of starters on chemical, biochemical, and sensory changes in Turkish white-brined cheese during ripening. J Dairy Sci. 2005;88:3460–3474. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(05)73030-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesenkaş H, Akbulut N. Yeasts as adjunct starter sultures used in cheese production. Ege Üniv Ziraat Fak Derg. 2006;43(2):165–174. [Google Scholar]

- Leclercq-Perlat MN, Corrieu G, Spinnier HE. Comparison of volatile compounds produced in model cheese medium deacidified by Debaryomyces hansenii or Kluyveromyces marxianus. J Dairy Sci. 2004;87:1545–1550. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(04)73306-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McSweeney P. Biochemistry of cheese ripening. Int J Dairy Technol. 2004;57(2/3):147–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0307.2004.00147.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McSweeney PLH, Fox PF. Chemical methods for the characterization of proteolysis in cheese during ripening. Lait. 1997;77:41–76. doi: 10.1051/lait:199713. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moio L, Addeo F. Grana Padano cheese aroma. J Dairy Res. 1998;65:317–333. doi: 10.1017/S0022029997002768. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Montel MC, Buchin S, Mallet A, Delbes-Paus C, Vuitton D, Desmasures N, et al. Traditional cheeses: rich and diverse microbiota with associated benefits. Int J Food Microbiol. 2014;177:136–154. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2014.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozturkoglu-Budak S, Figge MJ, Houbraken J, de Vries RP. The diversity and evolution of microbiota in traditional Turkish Divle Cave cheese during ripening. Int Dairy J. 2016;58:50–53. doi: 10.1016/j.idairyj.2015.09.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ozturkoglu-Budak S, Wiebenga A, Bron PA, de Vries RP. Protease and lipase activities of fungal and bacterial strains derived from an artisanal raw ewe’s milk cheese. Int J Food Microbiol. 2016;237:17–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2016.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozturkoglu-Budak S, Gursoy A, Aykas DP, Koçak C, Dönmez S, de Vries RP, Bron PA. Volatile compound profiling of Turkish Divle Cave cheese during production and ripening. J Dairy Sci. 2016;99(7):1–12. doi: 10.3168/jds.2015-10828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pena-Serna C, Penna A, Lopes Filho J. Zein-based blend coatings: impact on the quality of a model cheese of short ripening period. J Food Eng. 2016;171:208–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2015.10.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Price EJ, Linforth RST, Dodd CER, Phillips CA, Hewson L, Hort J, Gkatzionis K. Study of the influence of yeast inoculum concentration (Yarrowia lipolytica and Kluyveromyces lactis) on blue cheese aroma development using microbiological models. Food Chem. 2014;145:464–472. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.08.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settanni L, Moschetti G. Non-starter lactic acid bacteria used to improve cheese quality and provide health benefits. Food Microbiol. 2010;27(6):691–697. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2010.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen LM, Gori K, Petersen MA, Jespersen L, Arneborg N. Flavour compound production by Yarrowia lipolytica, Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Debaryomyces hansenii in a cheese-surface model. Int Dairy J. 2011;21:970–978. doi: 10.1016/j.idairyj.2011.06.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa MJ, Ardö Y, McSweeney PLH. Advances in the study of proteolysis during cheese ripening. Int Dairy J. 2001;11:327–345. doi: 10.1016/S0958-6946(01)00062-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tekin A, Hayaloglu AA. Understanding the mechanism of ripening biochemistry and flavour development in brine ripened cheeses. Int Dairy J. 2023;137:105508. doi: 10.1016/j.idairyj.2022.105508. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tsigie YA, Wang C, Kasim NS, Diem Q, Huynh L, Ho Q, Truong C, Ju Y. Oil Production from Yarrowia lipolytica Po1g using rice bran hydrolysate. J Biotechnol Biomed. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/378384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyay VK, McSweeney PLH, Magboul AAA, Fox PF. Proteolysis in cheese during ripening. In: McSweeney PLH, Fox P, Cotter P, Everett D, editors. Cheese: Chemistry, Physics and Microbiology. Academic Press London; 2004. pp. 273–300. [Google Scholar]

- Yalçın S, Ergül Ş, Özbaş Z. Importance of yeasts in cheese microflora. GIDA. 2011;36(1):55–62. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Huang C, Johansen PG, PetersenMA PMM, Lund MN, Jespersen L, Arneborg N. The utilisation of amino acids by Debaryomyces hansenii and Yamadazyma triangularis associated with cheese. Int Dairy J. 2021;121:105135. doi: 10.1016/j.idairyj.2021.105135. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.