Abstract

Prior work implicates sleep disturbance in the development and maintenance of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). However, the majority of this literature has focused on combat veteran men, and limited work has examined links between sleep disturbance and PTSD symptoms in sexual assault survivors. This is a notable gap in the literature, as sexual trauma is disproportionately likely to result in PTSD and is more common in women. We sought to examine the relations between subjective sleep disturbance, sexual assault severity, and PTSD symptoms in a sample of sexual assault survivors with PTSD (PTSD+), without PTSD (PTSD−), and healthy controls. The sample (N = 60) completed the Insomnia Severity Index and prospectively monitored their sleep for one week using the Consensus Sleep Diary. The sexual assault survivors also completed the Sexual Experiences Survey and PTSD Checklist-5. Results of group comparisons found that the PTSD+ group reported significantly higher insomnia symptoms, longer sleep onset latency, more nocturnal awakenings, and lower sleep quality compared to the healthy control group and higher insomnia symptoms compared to the PTSD− group. Results of regression analyses in the sexual assault survivors found that insomnia symptoms and number of nocturnal awakenings were significantly associated with higher PTSD symptoms, and sexual assault severity was significantly associated with higher insomnia symptoms, longer sleep onset latency, and lower sleep quality. These findings highlight specific features of sleep disturbance that are linked to trauma and PTSD symptom severity among sexual assault survivors.

Keywords: sleep, insomnia, PTSD, sexual assault, trauma

Nearly 70% of individuals are exposed to one or more traumas in their lifetime (Kessler et al., 2017), and those who experience sexual trauma may be particularly vulnerable to developing posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Approximately 1 in 5 women and 1 in 14 men are survivors of sexual assault (Smith et al., 2018), and sexual assault accounts for approximately 43% of PTSD cases (Kessler et al., 2017). Indeed, the risk of developing PTSD following sexual assault exposure is estimated to range from 20-68% (Foa, 1997; Kessler et al., 2017; Shalev et al., 2017), which is substantially higher than the average risk of developing PTSD following any trauma exposure (i.e., 45%; Kessler et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2017). One factor that may contribute to the risk of developing PTSD after sexual assault is sleep disturbance (i.e., insomnia, difficulty with sleep initiation and maintenance, reduced sleep duration, and reduced sleep efficiency). Nearly 70% of individuals with PTSD report sleep disturbances (Belleville et al., 2009), resulting in high rates of comorbidity between sleep disorders and PTSD (Cox & Olatunji, 2020; Krakow et al., 2015).

Within the context of PTSD, sleep disturbances independently account for variability in depressive symptoms (Martindale et al., 2021), suicide risk (Healy & Vujanovic, 2021; McCarthy et al., 2021), and symptom severity (Gerhart et al., 2014). Further, sleep disturbances prior to deployment predict subsequent onset of PTSD and depression in veterans (Gehrman et al., 2013; Koffel et al., 2013), and sleep disturbance in the month prior to a motor vehicle accident predicts subsequent development of PTSD in community adults (Neylan et al., 2021), suggesting sleep disturbance may be a risk factor for developing PTSD after a traumatic event. There is also preliminary evidence that sleep disturbance may contribute to PTSD treatment outcomes. Indeed, sleep plays an important role in mechanisms of exposure therapy, including fear extinction and safety learning (Colvonen, Straus, et al., 2019; Pace-Schott et al., 2015). Conversely, sleep disturbance impairs fear extinction recall (Straus et al., 2017), strengthens the relation between PTSD symptom severity and poor fear extinction recall (Zuj et al., 2018), and predicts poorer treatment outcomes for individuals with PTSD (Sandahl et al., 2021). Thus, there is a robust relation between sleep disturbance and PTSD; however, it remains unclear if and how this relation varies by trauma type.

Although considerable work has examined the relation between sleep disturbance and PTSD in male combat veterans (Cox & Olatunji, 2016), few studies have focused on this relation in victims of sexual assault, and extant findings are mixed. One study in veterans found that those with military sexual trauma reported worse insomnia symptoms than those without military sexual trauma (Jenkins et al., 2015). Further, a study of sexual assault survivors (95% with PTSD) with insomnia symptoms and nightmares found that sleep disturbance severity was associated with more severe PTSD symptoms (Krakow et al., 2001). Notably, only two studies to date have compared sleep in sexual assault survivors with PTSD to that of a control group. A recent study found that female sexual assault survivors with PTSD reported poorer sleep quality and worse insomnia symptoms compared to healthy controls, and improved sleep quality was associated with improved PTSD symptoms over 1 year (Yeh et al., 2021). However, when comparing sleep measured by polysomnography (PSG) in a laboratory setting, there were no significant differences in sleep continuity or sleep architecture between those with PTSD and healthy controls, and those with PTSD showed reduced arousals compared to healthy controls. Similar results were observed in a recent study, which found worse subjective sleep disturbance in female sexual assault survivors with PTSD compared to female sexual assault survivors without PTSD and healthy controls (Lipinska & Thomas, 2017), whereas PSG-measured sleep largely did not differ between the three groups. Both authors speculated that sexual assault survivors with PTSD may sleep better in a new bed if their home bed or bedroom is associated with reminders of their assault (Lipinska & Thomas, 2017; Yeh et al., 2021). However, in the absence of prospectively monitored sleep in the home environment (i.e., sleep measured day to day), it is difficult to know whether sleep is improved in the laboratory or if sleep disturbance is overestimated by retrospective self-report measures.

It is also unclear whether there is a link between sexual trauma severity and sleep disturbance. It has long been presumed that trauma severity is linked to PTSD symptom severity (Kulka et al., 1990). Indeed, sexual assault severity is positively associated with PTSD symptoms (Pegram & Abbey, 2019), self-stigma following trauma (Deitz et al., 2015), and trauma-related shame (Decou et al., 2019). Additionally, sexual assault severity is indirectly associated with perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness (Decou et al., 2019), two risk factors for suicide. However, despite sleep disturbance being a symptom of PTSD, no study has examined the relation between sexual assault severity and sleep disturbance severity. It is plausible that greater sexual assault severity leads to greater sleep disturbance severity, given the evidence for a link between sexual assault severity and overall PTSD symptom severity (Pegram & Abbey, 2019) and the likelihood that the trauma occurred in the bed or bedroom. In light of findings that sleep disturbance is a risk factor for the subsequent development of PTSD (Gehrman et al., 2013; Koffel et al., 2013; Neylan et al., 2021), evidence for a relation between sexual assault severity and sleep disturbance may suggest that sleep disturbance is an intermediate process between sexual trauma and PTSD; that is, more severe sexual assaults may result in more disturbed sleep, which in turn confers vulnerability for PTSD.

Previous research has found that sleep disturbance is a hallmark of PTSD (Germain, 2013), particularly following combat-related trauma (DeViva et al., 2021). However, relatively less is known about the role of sleep disturbance in sexual assault-related PTSD. The present study sought to address this gap in the literature by examining prospective subjective sleep in adults with a history of sexual assault with (PTSD+) and without PTSD (PTSD−) and healthy controls. We hypothesized that sleep disturbance would distinguish the PTSD+ group from the PTSD− group and healthy controls and that sleep disturbance would be associated with PTSD symptom severity in the PTSD+ and PTSD− groups. We conducted exploratory analyses to examine the associations between sexual assault severity and sleep disturbance.

Methods

Participants

The sample consisted of adults who experienced a sexual assault after age 14 and healthy controls (N=66). Two participants endorsed moderate to high suicidality on the MINI (see below) and were withdrawn from the study. Four participants withdrew after session 1, leaving a final sample of 60 participants. Of the participants who experienced a sexual assault, 19 met criteria for PTSD (PTSD+; 31.7%), and 20 did not meet criteria for PTSD (PTSD−; 33.3%). Twenty-one participants were healthy controls (35%). The mean age was 33.20 years (SD = 13.46), ranging from 18 to 69 years. The majority of participants were female (n = 51; 85%), and the racial composition was as follows: White (n = 31; 51.7%), African American (n = 12; 20%), Hispanic/Latino (n = 2; 3.3%), Asian (n = 6; 10%), other (n = 6; 10%), or did not respond (n = 3; 5%). Thirty-four (56.7%) participants participated prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, and 26 (43.3%) participated during the COVID-19 pandemic. See Table 1 for demographics by diagnostic group.

Table 1.

| PTSD+ | PTSD− | Healthy controls | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | M = 38.33, SD = 14.11 | M = 35.32, SD = 15.07 | M = 26.21, SD = 7.44 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 2 (10.5%) | 1 (5.0%) | 2 (9.5%) |

| Female | 16 (84.2%) | 17 (85.0%) | 18 (85.7%) |

| Did not respond | 1 (5.3%) | 2 (10%) | 1 (4.8%) |

| Race | |||

| White | 11 (57.9%) | 14 (70%) | 6 (28.6%) |

| African American/Black | 6 (31.6%) | 3 (15%) | 3 (14.3%) |

| Asian/Asian American | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (28.6%) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 1 (5.3%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4.8%) |

| Other | 2 (10%) | 4 (19.0%) | |

| Did not respond | 1 (5.3%) | 1 (5.3%) | 1 (4.8%) |

| Participated before COVID-19 | 2 (10.5%) | 17 (85%) | 15 (71.4%) |

Measures

Diagnostic Status

The MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI; Sheehan et al., 1998) is a well-validated and widely used semi-structured diagnostic interview that assesses common DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) disorders. The MINI was used to determine diagnostic status. The MINI was administered by trained lab personnel who completed extensive training and supervision from the last author, who is a licensed clinical psychologist.

Trauma and PTSD symptoms

The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5; Weathers et al., 2013) is a 20-item measure of DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) PTSD symptoms in the past month. The PCL consists of four subscales consistent with the DSM-5 symptom clusters (i.e., intrusions, avoidance, negative alterations in cognition and mood, arousal and reactivity). Items are rated on a Likert scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). A score of 31-33 or higher is suggestive of probable PTSD (Bovin et al., 2015). The PCL demonstrated good internal consistency in the present study (α = .96).

The Sexual Experiences Survey (SES; Koss et al., 2007) is a measure of the severity of sexual assault experiences faced by participants in the past 12 months and since age 14. Items describe various sexual assault experiences and ask the participant to indicate if the experience happened 0 times, 1 time, 2 times, or 3+ times. The SES was scored using the “Separated outcomes and tactics severity-ranking scheme” (Davis et al., 2014). Sexual assault experiences were separated into the following categories, which were ranked in order from 0 through 9: No history of sexual assault, Sexual contact by verbal coercion, Sexual contact by intoxication, Sexual contact by physical force, Attempted rape by intoxication, Attempted rape by physical force, Completed rape by verbal coercion, Completed rape by intoxication, and Completed rape by physical force. This score (0-9) was then multiplied by the number of times the experience occurred. For example, if a participant experienced “Completed rape by physical force” twice, this would correspond to a score of 18. This was repeated for experience and scores were summed to produce a severity score from 0 to 135. The SES demonstrated good internal consistency in the present study (α = .91).

Sleep disturbance

The Consensus Sleep Diary (CSD; Carney et al., 2012) is a 9-item sleep diary that asks participants about their last night of sleep. The CSD was developed by a panel of sleep experts to create a standard sleep diary for the assessment of daily sleep. Components of sleep examined in the present study included sleep onset latency, wake after sleep onset, number of awakenings, sleep duration, sleep quality, sleep efficiency (sleep duration/time in bed multiplied by 100), and mid-sleep (calculated as the midpoint between sleep onset and sleep offset; converted to decimal format [i.e., minutes divided by 60 to reflect a proportion of an hour]).

The Insomnia Severity Index (ISI; Bastien, Vallieres, & Morin, 2001) is a 7-item self-report measure of insomnia symptoms over the past two weeks and is used to detect cases of insomnia and assess treatment response. Items on the ISI are rated on a Likert scale from 0 (none) to 4 (very severe), and higher scores indicate higher insomnia symptom severity. The ISI demonstrated good internal consistency (α = 0.94) in the present study.

Procedure

All procedures were approved by the university Institutional Review Board. Participants were recruited through advertisements placed on campus and in local mental health clinics and through a university research listserv. Advertisements were tailored to the groups, such that one set of advertisements were for individuals who had “previously experienced a sexual assault” and another set were for “healthy controls.” Potential participants were screened via phone prior to enrollment in the study. Participants included in the PTSD+ group endorsed a sexual assault after age 14, identified the sexual assault as their most traumatic experience if they endorsed multiple criterion A traumas, met criteria for PTSD, and denied current or previous bipolar disorder, psychotic disorder, or pervasive developmental disorder. Participants included in the PTSD− group endorsed a sexual assault after age 14, did not meet criteria for PTSD, and denied current or previous bipolar disorder, psychotic disorder, or pervasive developmental disorder. Participants were included in the healthy control group if they did not meet criteria for any major DSM-5 disorder on the MINI, denied clinically significant insomnia symptoms (ISI < 8), and denied taking medication for depression, anxiety, or sleep disturbance. All potential participants provided verbal informed consent for screening and written informed consent prior to enrollment in the study. Participants were excluded from the study following enrollment if they endorsed moderate to high suicidality on the MINI.

On day 1, participants attended a laboratory session (visit 1) that included informed consent and administration of the MINI, SES, PCL, and ISI (healthy control participants were not administered the SES or PCL). On days 2 through 8, participants completed the CSD upon awakening each morning. On day 9, participants returned to the laboratory to be debriefed (visit 2). Following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, visits 1 and 2 were completed via Zoom.

Data analysis

Two outlier values (i.e., values 1.5*interquartile range above the 3rd quartile) were identified for sleep onset latency and removed from analyses using this variable. We conducted one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to examine differences between the PTSD+, PTSD−, and healthy control groups on insomnia symptoms and sleep disturbance variables from the CSD. Tests of model assumptions revealed the assumption of homogeneity of variance was violated; we therefore utilized the Welch test for the ANOVAs and the Games-Howell post-hoc test for post-hoc comparisons between groups. Omega squared was used to evaluate effect size using standard thresholds (e.g., .01 = small, .06 = medium, .14 = large).

We then conducted follow-up linear regression models in the combined trauma sample (PTSD+ and PTSD−) for components of sleep disturbance that emerged as significantly different between groups (insomnia symptoms, sleep onset latency, number of awakenings, sleep quality). We first tested 4 linear regression models to examine the association between insomnia symptoms, sleep onset latency, number of awakenings, and sleep quality and PTSD symptom severity. We excluded the items assessing nightmares and sleep disturbance from the PCL total scores for these models, to avoid symptom overlap. Mean imputation was used to retain two participants with missing data on one PCL item. We next tested 4 linear regression models to examine the association between sexual assault severity and insomnia symptoms, sleep onset latency, number of awakenings, and sleep quality. Standardized beta values were used to evaluate effect size using standard thresholds (e.g., .10 = small, .30 = medium, .50 = large).

Bivariate correlations revealed that gender, age, and race were unrelated to any outcomes and therefore were not included in the regression models. The majority of PTSD+ participants participated in the study during the COVID-19 pandemic (89.5%), whereas the majority of PTSD− participants participated prior to the COVID-19 pandemic (85.0%); therefore, we were unable to include time of participation as a covariate. All analyses were conducted in SPSS 28.

Results

Descriptive statistics and associations between study variables

As expected, the PTSD+ group reported significantly higher PTSD symptoms (M = 41.89, SD = 18.34) compared to the PTSD− group (M = 11.40, SD = 9.98), t(27.08) = 6.06, p < .001, d = 2.01. Likewise, the PTSD+ group reported significantly higher sexual assault severity (M = 80.94, SD = 43.40) compared to the PTSD− group (M = 53.16, SD = 34.52), t(35) = 2.16, p < .05, d = .71.

There was a large, positive correlation between PTSD symptoms and insomnia symptoms (p < .001) and a medium positive correlation between PTSD symptoms and number of awakenings (p < .05). There were medium, positive correlations between sexual assault severity and insomnia symptoms (p < .001) and sleep onset latency (p < .05) and a medium, negative correlation between sexual assault severity and sleep quality (p < .05). There was a medium, positive correlation between sexual assault severity and PTSD symptoms (p < .001). See Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlations (N = 60)

| Measure | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. ISI | -- | |||||||||

| 2. SOL | .38** | -- | ||||||||

| 3. NWAK | .37** | .29* | -- | |||||||

| 4. WASO | .40** | .10 | .47** | -- | ||||||

| 5. Sleep quality | −.51** | −.33* | −.50** | −.32* | -- | |||||

| 6. Sleep timing | .03 | .11 | −.08 | −.13 | −.07 | -- | ||||

| 7. Sleep duration | −.27 | −.09 | −.22 | −.37** | .39** | .05 | -- | |||

| 8. Sleep efficiency | −.45** | −.42** | −.34* | −.61** | .54** | .08 | .49** | -- | ||

| 9. SES | .43** | .41* | .11 | .23 | −.42* | .08 | −.04 | −.08 | -- | |

| 10. PCL | .72** | .15 | .42* | .32 | −.35 | .34 | −.36 | −.27 | .36* | -- |

|

| ||||||||||

| M | 10.46 | 21.35 | 1.88 | 23.54 | 3.41 | 3.86 | 420.93 | 79.95 | 66.68 | 28.03 |

| SD | 7.62 | 19.29 | 1.40 | 26.62 | 0.75 | 1.60 | 70.58 | 12.15 | 41.03 | 21.44 |

| Range | 0-27 | 0-95 | 0-6.3 | 0-97.7 | 1.7-4.7 | 0.55-8.0 | 240-533 | 38.3-96.4 | 8-135 | 0-69 |

Note. PCL = PTSD Checklist for DSM-5; SES = Sexual Experiences Survey; ISI = Insomnia Severity Index; MEQ = Morningness-Eveningness Questionnaire; SOL = sleep onset latency; WASO = wake after sleep onset; NWAK = number of awakenings.

SOL, WASO, and sleep duration are reported in minutes. Mid-sleep is reported in decimal format. The PCL and SES were only administered to the PTSD+ and PTSD− groups (n = 39).

p < .05

p < .01

Group differences in sleep disturbance

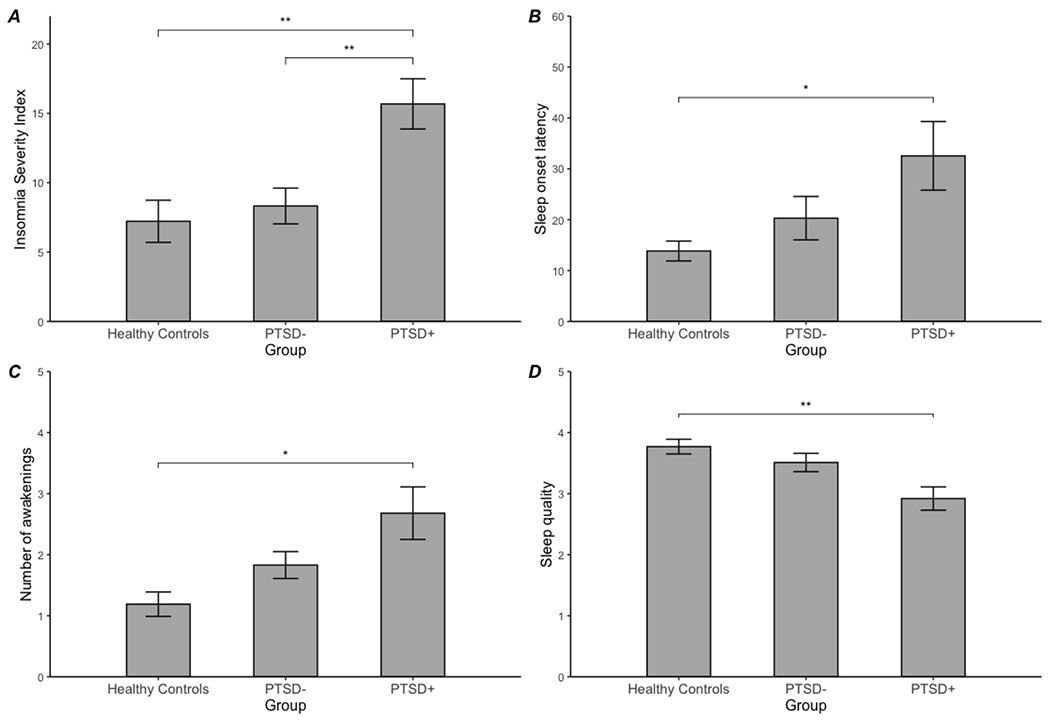

ANOVA results revealed large, significant differences between the PTSD+, PTSD−, and healthy control groups in insomnia symptoms, F(2, 34.66) = 7.23, p < .01, ω2 = .22, sleep onset latency, F(2, 24.43) = 4.01, p < .05, ω2 = .12, number of awakenings, F(2, 32.29) = 5.71, p < .01, ω2 = .17, and sleep quality, F(2, 33.35) = 6.94, p < .01, ω2 = .20. The PTSD+, PTSD−, and healthy control groups did not significantly differ in wake after sleep onset, sleep duration, sleep efficiency, or sleep timing (p’s > .05).

Post-hoc comparisons revealed that the PTSD+ group reported significantly higher insomnia symptoms (M = 15.68, SD = 7.89) than the PTSD− group (M = 8.32, SD = 5.63, p < .01) and the healthy control group (M = 7.22, SD = 6.46, p < .01). The PTSD− and healthy control groups did not significantly differ in insomnia symptoms (p = .85). In contrast, though the PTSD+ group reported significantly longer sleep onset latency (M = 32.55, SD = 26.13) compared to the healthy control group (M = 13.85, SD = 8.71, p < .05), the PTSD+ group did not significantly differ from the PTSD− group in sleep onset latency (M = 20.30, SD = 17,60, p = .29), nor did the PTSD− and healthy control groups differ in sleep onset latency (p = .37). Likewise, the PTSD+ group reported significantly more awakenings (M = 2.68, SD = 1.81) than the healthy control group (M = 1.19, SD = .91, p < .05), but the PTSD+ group did not significantly differ from the PTSD− group in number of awakenings (M = 1.83, SD = .90, p = .20), nor did the PTSD− and healthy control groups differ in number of awakenings (p = .09). Finally, the PTSD+ group reported significantly lower sleep quality (M = 2.92, SD = .82) than the healthy control group (M = 3.76, SD = .53, p < .01), and trended towards lower sleep quality than the PTSD− group (M = 3.51, SD = .64, p =.06). The PTSD− and healthy control groups did not significantly differ in sleep quality (p = .36). See Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Group comparisons of insomnia symptoms (panel A), sleep onset latency (panel B), number of awakenings (panel C), and sleep quality (panel D) between sexual assault survivors with PTSD (PTSD+), without PTSD (PTSD−), and healthy controls.

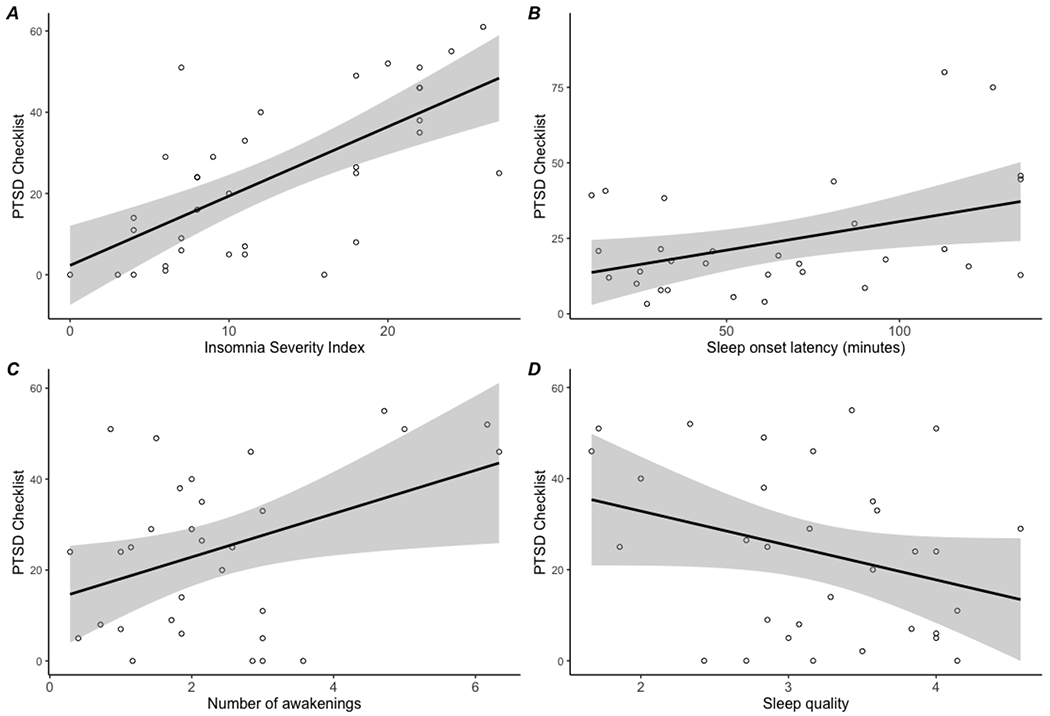

Associations between sleep disturbance and PTSD symptoms

Linear regression models revealed medium, significant associations between higher insomnia symptoms and higher PTSD symptoms, β = .43, p < .01, and more awakenings and higher PTSD symptoms, β = .35, p < .05. Sleep quality and sleep onset latency were unrelated to PTSD symptoms (p’s > .05). See Table 3 and Figure 2.

Table 3.

Coefficients for models associating sleep disturbance with PTSD symptoms in the combined PTSD+ and PTSD− groups (n = 39).

| Outcome: PCL | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| Predictor | B | SE | β | t | p | Predictor | B | SE | β | t | p |

|

| |||||||||||

| ISI | 1.71 | .32 | .68 | 5.27 | <.001 | SOL | .09 | .15 | .12 | .60 | .55 |

|

| |||||||||||

| Predictor | B | SE | β | t | p | Predictor | B | SE | β | t | p |

|

| |||||||||||

| NWAK | 4.77 | 2.04 | .40 | 2.34 | <.05 | Sleep quality | −7.55 | 4.19 | −.31 | −1.80 | .08 |

Note. PCL = PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (sleep disturbance and nightmare items removed); ISI = Insomnia Severity Index; SOL = sleep onset latency (reported in minutes); NWAK = number of awakenings.

Figure 2.

Linear regression models for associations between insomnia symptoms (panel A), sleep onset latency (panel B), number of awakenings (panel C), and sleep quality (panel D) and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms.

Associations between sexual trauma severity and sleep disturbance

Linear regression models revealed medium, significant associations between more severe sexual trauma and higher insomnia symptoms, β = .43, p < .05, longer sleep onset latency, β = .41, p < .05, and lower sleep quality, β = −.42, p < .05. Sexual trauma severity was unrelated to number of awakenings (p > .05). See Table 4 and Figure 3.

Table 4.

Coefficients for models associating sexual trauma severity with sleep disturbance in the combined PTSD+ and PTSD− groups (n = 39).

| Outcome | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| ISI | SOL | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Predictor | B | SE | β | t | p | B | SE | β | t | p |

|

| ||||||||||

| SES | .08 | .03 | .43 | 2.75 | <.05 | .19 | .08 | .41 | 2.41 | <.05 |

|

| ||||||||||

| NWAK | Sleep quality | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Predictor | B | SE | β | t | p | B | SE | β | t | p |

|

| ||||||||||

| SES | .004 | .006 | .11 | .65 | .52 | −.008 | .003 | −.42 | −2.63 | <.05 |

Note. SES = Sexual Experiences Survey; ISI = Insomnia Severity Index; SOL = sleep onset latency (reported in minutes); NWAK = number of awakenings.

Figure 3.

Linear regression models for associations between sexual assault severity and insomnia symptoms (panel A), sleep onset latency (panel B), number of awakenings (panel C), and sleep quality (panel D).

Discussion

The present study examined sleep disturbance in sexual assault survivors with and without PTSD and healthy controls. Compared to healthy controls, sexual assault survivors with PTSD reported longer sleep onset latency, more nocturnal awakenings, and lower sleep quality. In contrast, there were no differences between sexual assault survivors with and without PTSD on any sleep diary metric. This is the first study to use prospective sleep monitoring to examine subjective sleep disturbance in sexual assault survivors and healthy controls, and our results differ from studies examining objectively measured sleep in sexual assault survivors. Indeed, prior work found no differences in objective sleep onset latency or number of awakenings between sexual assault survivors with and without PTSD (Lipinska & Thomas, 2017) and healthy controls (Lipinska & Thomas, 2017; Yeh et al., 2021). Notably, few studies have utilized prospective subjective sleep monitoring to examine sleep disturbance in PTSD resulting from other forms of trauma, and results are mixed. Consistent with the present findings, two prior studies also found increased sleep onset latency in those with PTSD compared to healthy controls (Straus et al., 2015; Van Liempt et al., 2013); however, these studies also found more wake after sleep onset (Straus et al., 2015; Van Liempt et al., 2013) and decreased sleep duration (Straus et al., 2015) in those with PTSD compared to healthy controls. Likewise, though one study found no differences in sleep onset latency, wake after sleep onset, or sleep duration between trauma-exposed individuals with and without PTSD on a sleep diary (Calhoun et al., 2007), another study found longer sleep onset latency and wake after sleep onset in individuals with PTSD compared to trauma-exposed controls (Van Liempt et al., 2013). Thus, additional research is needed to clarify discrepant findings for prospectively monitored subjective sleep in PTSD, particularly in sexual assault survivors.

An important finding in the present study is that the only aspect of subjective sleep disturbance that distinguished sexual assault survivors with and without PTSD was insomnia symptoms. Specifically, sexual assault survivors with PTSD reported higher insomnia symptoms compared to sexual assault survivors without PTSD and healthy controls. These findings are consistent with one extant study which also found higher insomnia symptoms in sexual assault survivors compared to healthy controls (Yeh et al., 2021), and this is the first study to demonstrate higher insomnia symptoms in sexual assault survivors with PTSD compared to sexual assault survivors without PTSD. These findings are also consistent with the broader PTSD literature which has likewise found higher insomnia symptoms in those with PTSD compared to trauma-exposed controls and healthy controls in veteran and mixed trauma samples (Cohen et al., 2013; Meyerhoff et al., 2014; Straus et al., 2015). One interpretation of these findings is that insomnia symptoms uniquely characterize PTSD, regardless of the nature of the trauma.

Among sexual assault survivors, higher insomnia symptoms and more awakenings were associated with increased PTSD symptom severity. Sleep onset latency and sleep quality were not significantly associated with PTSD symptom severity, though the latter effect was at trend level. Two prior studies examining associations between sleep disturbance and PTSD symptom severity in sexual assault survivors found that more retrospective sleep disturbance is associated with worse PTSD symptoms concurrently (Krakow et al., 2001) and after one year of PTSD treatment (Yeh et al., 2021). Likewise, several studies have found an association between retrospective sleep disturbance and PTSD symptom severity in other trauma types (Belleville et al., 2009; Casement et al., 2012; Giosan et al., 2015), including insomnia symptoms specifically (Fairholme et al., 2013; Krakow et al., 2004; Werner et al., 2016). Notably, two studies finding minimal evidence for associations between prospectively monitored subjective sleep and PTSD symptom severity did not assess number of awakenings (Kobayashi & Delahanty, 2013; Werner et al., 2016). Experimental sleep fragmentation (i.e., begin woken from sleep repeatedly) has been found to result in cognitive and emotional consequences relevant to PTSD, including decreased inhibitory control (Lee et al., 2022) and positive affect (Finan et al., 2017). Thus, sleep fragmented by multiple nocturnal awakenings may contribute to increased PTSD symptoms through dysregulated emotional processes. Alternatively, nocturnal awakenings may reflect hypervigilance among those with PTSD. Longitudinal studies that follow sexual assault survivors immediately after the event are needed to determine the direction of the relation between nocturnal awakenings and PTSD symptoms.

Exploratory analyses also revealed that more severe sexual assault experience was associated with higher insomnia symptoms, longer sleep onset latency, and worse sleep quality. In contrast, sexual assault severity was unrelated to number of awakenings. To our knowledge, no studies to date have examined the relationship between sexual assault severity and sleep disturbance symptoms. As prior research has speculated (e.g., Lipinska & Thomas, 2017; Yeh et al., 2021), it may be the case that individuals with sexual assault experiences learn to associate their bed with the trauma, resulting in poorer sleep quality. Indeed, associative learning principles have long provided insight into how intrusive memories are cued and retrieved in PTSD (e.g., Clark & Ehlers, 2000; Gillihan & Foa, 2011). For individuals who have experienced more severe and/or multiple instances of sexual assault, this association may be strengthened and/or repeatedly reinforced. Thus, as the individual confronts the bed (i.e., conditioned stimulus), they are reminded of the assault and experience increased levels of fear and arousal (i.e., conditioned response). Such arousal is inconsistent with sleep and may result in greater difficulty falling asleep (sleep onset latency), poorer sleep quality, and increased insomnia symptoms (e.g., dissatisfaction, distress, and interference with sleep). Notably however, sexual assault symptom severity was not significantly associated to number of awakenings, suggesting the severity of the traumatic experience may not interfere with an individual’s ability to stay asleep. Although the present study provides novel insight into this relationship with prospective sleep data, it will be important for future research to closely examine how sexual assault severity may predict sleep disturbance outcomes across multiple levels of analysis. Likewise, longitudinal designs are needed to determine whether more severe sexual trauma disrupts sleep in the period immediately following the trauma, and whether this sleep disturbance confers risk for the development of PTSD. Indeed, prior studies have found that sleep disturbances mediate the relation between trauma severity and PTSD symptoms in military personnel (Picchioni et al., 2010; Steele et al., 2017) and Syrian refugees (Lies et al., 2020), highlighting the need to examine such a causal pathway in sexual assault survivors.

The evidence for increased insomnia symptoms, longer sleep onset latency, more nocturnal awakenings, and worse sleep quality in sexual assault survivors with PTSD and the links between these aspects of sleep disturbance and sexual assault and PTSD symptom severity suggest that sleep disturbance may be an important target for clinical intervention in this population. Indeed, residual sleep disturbance is common following PTSD treatment (Pruiksma et al., 2016; Zayfert & De Viva, 2004), and residual insomnia symptoms are associated with poorer treatment outcome (López et al., 2019), highlighting a need for intervention approaches to address sleep specifically. Indeed, cognitive behavior therapy for insomnia (CBTI) has been found to decrease nightmares in adults with PTSD (Talbot et al., 2014), and a recent pilot study found large effects for a treatment integrating CBTI with prolonged exposure (Colvonen, Drummond, et al., 2019). Likewise, a recent pilot trial of light therapy for PTSD found medium to large improvements in sleep and large improvements in PTSD symptoms (Zalta et al., 2019). Additional work is needed to examine whether sleep-focused treatments improve PTSD symptoms in sexual assault survivors.

Although this is the first study to use prospective monitoring to examine the role of subjective sleep disturbance in sexual assault-related PTSD, the limitations of this study must also be considered. First, data collection was initiated prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and completed during the pandemic; thus, stress experienced during the pandemic may have influenced the sleep and PTSD symptoms of some participants. Second, the sample size was relatively small, and it is possible that smaller group differences and/or relations between sleep disturbance, PTSD symptoms, and trauma severity were undetected. Second, we did not include behavioral or physiological measures of PTSD. Relatedly, although the MINI has been used in previous research to diagnose PTSD, future research may benefit from using a PTSD-specific diagnostic interview (e.g., the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale). Further, we did not include an objective measure of sleep, such as actigraphy or polysomnography; thus, we are unable to examine group differences in sleep architecture or potential discrepancies between objective and subjective sleep disturbance. Still, we suggest that the use of subjective prospective monitoring has two benefits. First, the ambulatory (rather than in-lab) design provides an opportunity to examine whether sleep continuity distinguishes sexual assault survivors from healthy controls when the participant is sleeping in their typical sleeping environment, given that authors of prior polysomnograpy-based studies have speculated that sexual assault survivors with PTSD may sleep better in a sleep laboratory if their home bed or bedroom is associated with reminders of their assault (Lipinska & Thomas, 2017; Yeh et al., 2021). Second, identifying subjective sleep correlates of PTSD symptom severity has greater clinical utility than sleep correlates measures by actigraphy or polysomnography, as a sleep diary is more feasible for typical clinical practice. However, we also acknowledge that 1 week may not be a sufficient time period to capture habitual sleep or PTSD symptoms; thus, future work on sleep disturbance in sexual trauma survivors should incorporate a multimethod approach that includes objective and subjective measures of sleep and PTSD symptoms over longer time periods. Finally, although our ordering of the variables in the regression models (i.e., sleep predicting PTSD symptoms, sexual trauma severity predicting sleep disturbance) was informed by theory and prior research (e.g., Gehrman et al., 2013; Koffel et al., 2013), the cross-sectional design precludes the ability to test the direction of these effects or make causal inferences. Prospective designs, particularly in individuals who have recently experienced a sexual assault, will be informative for understanding the pathways between sexual trauma, sleep disturbance, and PTSD symptoms.

Highlights.

PTSD+ sexual assault survivors report more sleep disturbances vs healthy controls

PTSD+ sexual assault survivors report higher insomnia symptoms vs PTSD−

Insomnia symptoms and awakenings associated with PTSD symptom severity

Assault severity associated with insomnia symptoms, sleep onset latency, quality

Acknowledgments.

The authors would like to acknowledge Nicole Davies, Leanna Duong, Max Luber, Angelee Parmar, Maria Sanin, and Yunshu Yang for their assistance with data collection.

Funding.

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health [F31MH113271] and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (T32 HL149646). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

CRediT authorship contribution statement. Rebecca C. Cox: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing-Original draft, Visualization, Funding acquisition. Alexa N. Garcia: Project Administration, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing-Original draft. Sarah C. Jessup: Project Administration, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing-Original draft. Sarah E. Woronko: Data Curation, Writing-Original draft. Catherine Rast: Data Curation, Writing-Original draft. Bunmi O. Olatunji: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Writing-Review and editing, Supervision.

Declaration of Interest. None

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders DSM-5. American Psychiatric Association. In DSM. 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.744053 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bastien CH, Vallieres A, & Morin CM (2001). Validation of the insomnia severity index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Medicine, 2, 297–307. 10.1080/15402002.2011.606766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belleville G, Guay S, & Marchand A (2009). Impact of sleep disturbances on PTSD symptoms and perceived health. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 197(2), 126–132. 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181961d8e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bovin MJ, Marx BP, Weathers FW, Gallagher MW, Rodriguez P, Schnurr PP, & Keane TM (2015). Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fifth Edition (PCL-5) in veterans. Psychological Assessment, 25(11), 1379–1391. 10.1037/pas0000254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun PS, Wiley M, Dennis MF, Means MK, Edinger JD, & Beckham JC (2007). Objective evidence of sleep disturbance in women with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 20(6), 1009–1018. 10.1002/jts.20255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney CE, Buysse DJ, Ancoli-Israel S, Edinger JD, Krystal AD, Lichstein KL, & Morin CM (2012). The Consensus Sleep Diary: Standardizing prospective sleep self-monitoring. Sleep, 35(2), 287–302. 10.5665/sleep.1642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casement MD, Harrington KM, Miller MW, & Resick PA (2012). Associations between Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index factors and health outcomes in women with posttraumatic stress disorder. Sleep Medicine, 13(6), 752–758. 10.1016/j.sleep.2012.02.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark D, & Ehlers A (2000). A cognitive model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 38(2), 319–345. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10761279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen DJ, Begley A, Alman JJ, Cashmere DJ, Pietrone RN, Seres RJ, & Germain A (2013). Quantitative electroencephalography during rapid eye movement (REM) and non-REM sleep in combat-exposed veterans with and without post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Sleep Research, 22(1), 76–82. 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2012.01040.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colvonen PJ, Drummond SPA, Angkaw AC, & Norman SB (2019). Piloting cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia integrated with prolonged exposure. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 11(1), 107–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colvonen PJ, Straus LD, Acheson D, & Gehrman P (2019). A review of the relationship between emotional learning and memory, sleep, and PTSD. Current Psychiatry Reports, 21(2). 10.1007/s11920-019-0987-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox RC, & Olatunji BO (2016). A systematic review of sleep disturbance in anxiety and related disorders. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 37, 104–129. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2015.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox RC, & Olatunji BO (2020). Sleep in the anxiety-related disorders: A meta-analysis of subjective and objective research. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 51, 101282. 10.1016/j.smrv.2020.101282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decou CR, Kaplan SP, Spencer J, & Lynch SM (2019). Trauma-related shame, sexual -assault severity, thwarted -belongingness, and -perceived-burdensomeness among female-undergraduate survivors of sexual assault. Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention, 40(2), 134–140. 10.1027/0227-5910/a000549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deitz MF, Williams SL, Rife SC, & Cantrell P (2015). Examining cultural, social, and self-related aspects of stigma in relation to sexual assault and trauma symptoms. Violence Against Women, 21(5), 598–615. 10.1177/1077801215573330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeViva JC, McCarthy E, Southwick SM, Tsai J, & Pietrzak RH (2021). The impact of sleep quality on the incidence of PTSD: Results from a 7-year, nationally representative, prospective cohort of U.S. military veterans. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 81, 102413. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2021.102413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairholme CP, Nosen EL, Nillni YI, Schumacher JA, Tull MT, & Coffey SF (2013). Sleep disturbance and emotion dysregulation as transdiagnostic processes in a comorbid sample. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 51(9), 540–546. 10.1016/j.brat.2013.05.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finan PH, Remeniuk B, Quartana PJ, Garland EL, Rhudy JL, Hand M, Irwin MR, & Smith MT (2017). Partial sleep deprivation attenuates the positive affective system: Effects across multiple measurement modalities. Sleep, 40(1), zsw017. 10.1093/sleep/zsw017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB (1997). Trauma and women: Course, predictors, and treatment. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 58, 25–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehrman P, Seelig AD, Jacobson IG, Boyko EJ, Hooper TI, Gackstetter GD, Ulmer CS, & Smith TC (2013). Predeployment sleep duration and insomnia symptoms as risk factors for new-onset mental health disorders following military deployment. Sleep, 36(7), 1009–1018. 10.5665/sleep.2798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhart JI, Hall BJ, Russ EU, Canettie D, & Hobfoll SE (2014). Sleep disturbances predict later trauma-related distress: Cross panel investigation amidst violent turmoil. Health Psychology, 33(4), 365–372. 10.1037/a0032572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germain A (2013). Sleep disturbances as the hallmark of PTSD: Where are we now? American Journal of Psychiatry, 170(4), 372–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillihan SJ, & Foa EB (2011). Fear extinction and emotional processing theory: A critical review. In Schachtman TR & Reilly SS (Eds.), Associative Learning and Conditioning Theory: Human and Non-Human Applications (pp. 27–43). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Giosan C, Malta LS, Wyka K, Jayasinghe N, Evans S, Difede J, & Avram E (2015). Sleep disturbance,disability, and posttraumatic stress disorder in utility workers. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 71(1), 72–84. 10.1002/jclp.22116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healy NA, & Vujanovic AA (2021). PTSD symptoms and suicide risk among firefighters: The moderating role of Sleep Disturbance. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 13(7), 749–758. 10.1037/tra0001059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins MM, Colvonen PJ, Norman SB, Afari N, Allard CB, & Drummond SPA (2015). Prevalence and mental health correlates of insomnia in first-encounter veterans with and without military sexual trauma. Sleep, 38(10), 1547–1554. 10.5665/sleep.5044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Benjet C, Bromet EJ, Cardoso G, Degenhardt L, de Girolamo G, Dinolova RV, Ferry F, Florescu S, Gureje O, Haro JM, Huang Y, Karam EG, Kawakami N, Lee S, Lepine J-P, Levinson D, … Koenen KC (2017). Trauma and PTSD in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 5(sup5), 1353383. 10.1080/20008198.2017.1353383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi I, & Delahanty DL (2013). Gender differences in subjective sleep after trauma and the development of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms: A pilot study. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 26, 467–474. 10.1002/jts.21828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koffel E, Polusny MA, Arbisi PA, & Erbes CR (2013). Pre-deployment daytime and nighttime sleep complaints as predictors of post-deployment PTSD and depression in National Guard troops. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 27(5), 512–519. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krakow B, Germain A, Warner TD, Schrader R, Koss M, Hollifield M, Tandberg D, Melendrez D, & Johnston L (2001). The relationship of sleep quality and posttraumatic stress to potential sleep disorders in sexual assault survivors with nightmares, insomnia, and PTSD. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 14(4), 647–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krakow B, Haynes PL, Warner TD, Santana E, Melendrez D, Johnston L, Hollifield M, Sisley BN, Koss M, & Shafer L (2004). Nightmares, insomnia, and sleep-disordered breathing in fire evacuees seeking treatment for posttraumatic sleep disturbance. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 17(3), 257–268. 10.1023/BJOTS.0000029269.29098.67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krakow B, Ulibarri VA, Moore BA, & Mciver ND (2015). Posttraumatic stress disorder and sleep-disordered breathing: A review of comorbidity research. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 24, 37–45. 10.1016/j.smrv.2014.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulka RA, Schlenger WE, Fairbank JA, Hough RL, Jordan BK, Marmar CR, & Weiss DS (1990). Trauma and the Vietnam war generation: Report of findings from the National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study. New York: Brunner/Mazel. [Google Scholar]

- Lies J, Drummond SPA, & Jobson L (2020). Longitudinal investigation of the relationships between trauma exposure, post-migration stress, sleep disturbance, and mental health in Syrian refugees. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11(1), 1825166,. 10.1080/20008198.2020.1825166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipinska G, & Thomas KGF (2017). Better sleep in a strange bed? Sleep quality in South African women with posttraumatic stress disorder. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1–14. 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Petukhova MV, Sampson NA, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Andrade LH, Bromet EJ, de Girolamo G, Haro JM, Hinkov H, Kawakami N, Koenen KC, Kovess-Masfety V, Lee S, Medina-Mora ME, Shahly V, Stein DJ, ten Have M, Torres Y, … Kessler RC (2017). Association of DSM-IV posttraumatic stress disorder with traumatic experience type and history in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. JAMA Psychiatry, 74(3), 270–281. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.3783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López CM, Lancaster CL, Wilkerson A, Gros DF, Ruggiero KJ, & Acierno R (2019). Residual insomnia and nightmares postintervention symptom reduction among veterans receiving treatment for comorbid PTSD and depressive symptoms. Behavior Therapy, 50(5), 910–923. 10.1016/j.beth.2019.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martindale SL, Lad SS, Ord AS, Nagy KA, Crawford CD, Taber KH, & Rowland JA (2021). Sleep moderates symptom experience in combat veterans. Journal of Affective Disorders, 282, 236–241. 10.1016/j.jad.2020.12.161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy E, Deviva JC, Southwick SM, & Pietrzak RH (2021). Self-rated sleep quality predicts incident suicide ideation in US military veterans: Results from a 7-year, nationally representative, prospective cohort study. Journal of Sleep Research, 31(1), e13447. 10.1111/jsr.13447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyerhoff DJ, Mon A, Metzler T, & Neylan TC (2014). Cortical gamma-aminobutyric acid and glutamate in posttraumatic stress disorder and their relationships to self-reported sleep quality. Sleep, 37(5), 893–900. 10.5665/sleep.3654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neylan TC, Kessler RC, Ressler KJ, Clifford G, Beudoin FL, An X, Stevens JS, Zeng D, Linnstaedt SD, Germine LT, Sheikh S, Storrow AB, Punches BE, Mohiuddin K, Gentile NT, McGrath ME, van Rooij SJH, Haran JP, Peak DA, … McLean SA (2021). Prior sleep problems and adverse post-traumatic neuropsychiatric sequelae of motor vehicle collision in the AURORA study. Sleep, 44(3), 1–11. 10.1093/sleep/zsaa200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pace-Schott EF, Germain A, & Milad MR (2015). Effects of sleep on memory for conditioned fear and fear extinction. Psychological Bulletin, 141(4), 835–857. 10.1037/bul0000014.Effects [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pegram SE, & Abbey A (2019). Associations between sexual assault severity and psychological and physical health outcomes: Similarities and differences among African American and Caucasian survivors. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 34(19), 4020–4040. 10.1177/0886260516673626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picchioni D, Cabrera OA, Mcgurk D, Thomas JL, Castro CA, Balkin TJ, Bliese PD, & Hoge CW (2010). Sleep symptoms as a partial mediator between combat stressors and other mental health symptoms in Iraq War veterans. Military Psychology, 22(3), 340–355. 10.1080/08995605.2010.491844 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pruiksma KE, Taylor DJ, Wachen JS, Mintz J, Young-McCaughan S, Peterson AL, Yarvis JS, Borah EV, Dondanville KA, Litz BT, Hembree EA, & Resick PA (2016). Residual sleep disturbances following PTSD treatment in active duty military personnel. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 8(6), 697–701. 10.1037/tra0000150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandahl H, Carlsson J, Sonne C, Mortensen EL, Jennum P, & Baandrup L (2021). Investigating the link between subjective sleep quality, symptoms of PTSD, and level of functioning in a sample of trauma-affected refugees. Sleep, 1–10. 10.1093/sleep/zsab063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalev A, Liberzon I, & Marmar CR (2017). Post-traumatic stress disorder. New England Journal of Medicine, 376, 2459–2469. 10.1056/NEJMra1612499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SG, Zhang X, Basile KC, Merrick MT, Kresnow M-J, & Chen J (2018). National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2015 Data brief-Updated release. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele M, Germain A, & Campbell JS (2017). Mediation and moderation of the relationship between combat experiences and post-traumatic stress symptoms in active duty military personnel. Military Medicine, 182(5/6), e1632. 10.7205/MILMED-D-16-00169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus LD, Acheson DT, Risbrough VB, & Drummond SPA (2017). Sleep deprivation disrupts recall of conditioned fear extinction. Biological Psychiatry, 2(2), 123–129. 10.1016/j.bpsc [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus LD, Drummond SPA, Nappi CM, Jenkins MM, & Norman SB (2015). Sleep variability in military-related PTSD: A comparison to primary insomnia and healthy controls. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 29, 8–16. 10.1002/jts.21982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talbot LS, Maguen S, Metzler TJ, Schmitz M, McCaslin SE, Richards A, Perlis ML, Posner DA, Weiss B, Ruoff L, Varbel J, & Neylan TC (2014). Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia in posttraumatic stress disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Sleep, 37(2), 327–341. 10.5665/sleep.3408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Liempt S, Arends J, Cluitmans PJM, Westenberg HGM, Kahn RS, & Vermetten E (2013). Sympathetic activity and hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis activity during sleep in post-traumatic stress disorder: A study assessing polysomnography with simultaneous blood sampling. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 38(1), 155–165. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner KB, Griffin MG, & Galovski TE (2016). Objective and subjective measurement of sleep disturbance in female trauma survivors with posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatry Research, 240, 234–240. 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.04.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh MSL, Poyares D, Coimbra BM, Mello AF, Tufik S, & Mello MF (2021). Subjective and objective sleep quality in young women with posttraumatic stress disorder following sexual assault: A prospective study. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1), 1934788. 10.1080/20008198.2021.1934788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalta AK, Bravo K, Valdespino-Hayden Z, Pollack MH, & Burgess HJ (2019). A placebo-controlled pilot study of a wearable morning bright light treatment for probable PTSD. Depression and Anxiety, 36(7). 10.1002/da.22897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zayfert C, & De Viva JC (2004). Residual insomnia following cognitive behavioral therapy for PTSD. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 17(1), 69–73. 10.1023/B:J0TS.0000014679.31799.e7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuj DV, Palmer MA, Malhi GS, Bryant RA, & Felmingham KL (2018). Greater sleep disturbance and longer sleep onset latency facilitate SCR-specific fear reinstatement in PTSD. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 110(May), 1–10. 10.1016/j.brat.2018.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]