Abstract

Polymer conjugation has been widely used to improve the stability and pharmacokinetics of therapeutic biomacromolecules; however, conventional methods to generate such conjugates often use disperse and/or achiral polymers with limited functionality. The heterogeneity of such conjugates may lead to manufacturing variability, poorly controlled biological performance, and limited ability to optimize structure-property relationships. Here, using insulin as a model therapeutic polypeptide, we introduce a strategy for the synthesis of polymer-protein conjugates based on discrete, chiral polymers synthesized through iterative exponential growth (IEG). These conjugates eliminate manufacturing variables originating from polymer dispersity and poorly controlled absolute configuration. Moreover, they offer tunable molecular features, such as conformational rigidity, that can be modulated to impact protein function, enabling faster or longer lasting blood glucose responses in diabetic mice when compared to PEGylated insulin and the commercial insulin variant Lantus. Furthermore, IEG-insulin conjugates showed no signs of decreased activity, immunogenicity, or toxicity following repeat dosing. This work represents a significant step toward the synthesis of precise synthetic polymer-biopolymer conjugates and reveals that synthetic polymer structure may be used to optimize such conjugates in the future.

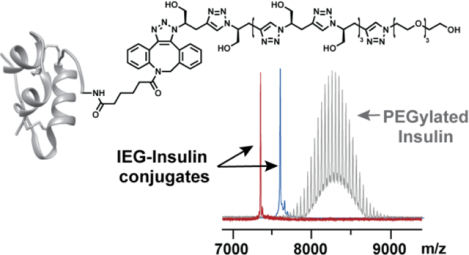

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction:

Biologics, such as protein and peptide therapeutics, play critical roles in modern medicine due to their excellent target specificity and safety.1 While the number of protein/peptide-based drugs in clinical trials is growing rapidly, intrinsic challenges such as rapid enzymatic degradation and limited biodistribution can significantly limit their activity in vivo.2 In addition, the poor stability of biopolymers under environmental stress or transportation complicates their manufacturing and equitable distribution.3 Covalent conjugation of polymers to therapeutic peptides/proteins offers a strategy to improve their stability, pharmacokinetics, and biodistribution through steric shielding and enhanced circulation time.4 In this regard, PEG has been the most commonly used synthetic polymer owing to its hydrophilicity, low immunogenicity, and demonstrated clinical track record.4–6 Nevertheless, PEG offers limited opportunities for property tuning and optimization as it lacks functional handles for derivatization.7 Moreover, while polypeptides are chiral, PEG is achiral, leaving an open question: how might synthetic polymer chirality impact biopolymer conjugate properties? The inherent molar mass distribution (“dispersity”) of conventional PEG may also introduce manufacturing challenges and batch-to-batch variation (Figure 1a).8,9 For instance, recent clinical studies of PEGylated IL-2 (Bempeg) revealed patient responses ranging from 75% to 36% with different drug batches, impeding clinical translation.10,11 Additionally, some PEGylated biomolecules, including PEGylated insulin derivatives, have shown undesirable liver toxicity,12 and while PEGylated therapeutics such as the mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccines have been given to millions of people safely, the observation of anti-PEG antibodies in a significant fraction of humans has motivated a search for suitable polymer alternatives; we note, however, that these alternatives typically do not have defined molar masses and configurations.7,13 Finally, while several examples of using discrete PEG for the formation of protein conjugates have been reported,14–16 it is not yet clear if these conjugates will display the same beneficial properties conferred by traditional PEGylation in a clinical context. Overall, the inherent lack of tunability of PEG motivates the search for discrete and chiral polymers that could be used to generate functional, discrete polymer–protein conjugates.

Figure 1. Representative protein-polymer conjugates and their characteristics.

a. Conventional PEGylation of proteins leads to a heterogeneous mixture of conjugates with limited control over their structures. b. Recombinant expression of XTEN-peptide conjugates offers a way of producing discrete polymer-biopolymer conjugates yet is limited to natural configurations and compositions. c. Discrete IEG-protein conjugates offer uniform products and tunable molecular features.

One promising strategy for discrete polymer-protein/peptide conjugate synthesis leverages recombinant expression to append unstructured, carrier polypeptides directly to functional polypeptides (Figure 1b). For example, the “XTEN” platform produces discrete therapeutic peptide-polypeptide conjugates where the latter component is an unstructured polypeptide optimized to provide many of the best features of PEGylation, such as enhanced stability, higher water solubility, and resistance to aggregation, but with a discrete, natural biopolymer. For example, XTEN conjugation significantly increased the in vivo half-life of the therapeutic peptide exenatide.17,18 While this approach is highly promising, it is currently limited to polypeptide backbones of natural chirality, which precludes broad exploration of structure, composition, and property space.

We are interested in studying how molecular descriptors such as absolute and relative configuration and conformational flexibility may offer new handles for tuning and optimizing the properties of discrete polymers19–21 in applications ranging from self-assembly22–25 to medicine.26 Indeed, while the impacts of relative configuration on polymer properties have been appreciated for decades, as perhaps best exemplified by polypropylene, far less is known about the role of absolute configuration (i.e., chirality), particularly in the context of biomedical applications where polymers are designed to interface with chiral biomolecules. We recently reported that bottlebrush polymers with chiral sidechains can display significant differences in blood pharmacokinetics (PK) and liver clearance in vivo as a function of their handedness, even when those polymers do not target a specific biomolecule, revealing that stereochemistry may offer a tool for tuning the biological properties of synthetic polymers.26 Moreover, recent studies have shown that nanoparticle chirality can drive significant changes in immune responses in vivo through receptor-mediated interactions.27 Nevertheless, to our knowledge, there are no reports of synthetic polymer–biopolymer conjugates that feature discrete molar masses, precise absolute and relative configurations, variable rigidity, and site-specific conjugation; thus, there are no studies that explore how the configurations and compositions of such polymers may impact conjugate functions. Notably, conjugation of even enantiomeric polymers, i.e., mirror image polymers that are not superimposable, to a protein would give diastereomeric conjugates that may display distinct biological properties.

Here, we introduce a novel class of discrete polymer-protein conjugates designed to address this challenge (Figure 1c). We selected insulin as a model protein due to its widespread use (~9 million and >60 million people worldwide take insulin drugs to treat Type I diabetes and Type II diabetes, respectively28) and its established potential for polymer conjugation. Several insulin variants, including long-acting (e.g., Lantus), and fast-acting (e.g., Lispro),29–31 have been engineered to meet the diverse administration requirements and optimal PK profiles of patients. Nevertheless, the properties of these derivatives are optimized through alteration of the amino acid sequence of insulin, which in turn alters its aggregation state and bioavailability.32–37 We hypothesized that the structures of discrete, chiral synthetic polymers conjugated to insulin could be used to tune the overall conjugate performance, providing an alternative strategy to protein engineering. To test this hypothesis, we used an iterative exponential growth (IEG) strategy to synthesize two series of discrete polymers with distinct backbone rigidities and absolute configurations.24–26,38 These polymers were then site-specifically conjugated to the N-terminus of the insulin B chain using a strain-promoted azide-alkyne cycloaddition (SPACC) reaction. Circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy suggested that the secondary structure of insulin was not significantly perturbed by IEG polymer conjugation, while diffusion ordered NMR (DOSY) studies suggested minimal differences in insulin aggregation in aqueous solution. Nevertheless, some IEG-insulin conjugates display faster-acting and longer-lasting blood glucose management performance in diabetic mice compared to PEGylated insulin and Lantus, while repeat dosing studies in healthy mice revealed no signs of immunogenicity or toxicity. Overall, these results demonstrate that the configuration and composition of discrete synthetic polymers can be leveraged to vary the properties of a therapeutically important protein without the need for modification of the protein sequence itself, offering a powerful approach to the design of future synthetic polymer–biopolymer conjugates.

2. Results and Discussion:

IEG synthesis of uniform, chiral polymers for insulin conjugation.

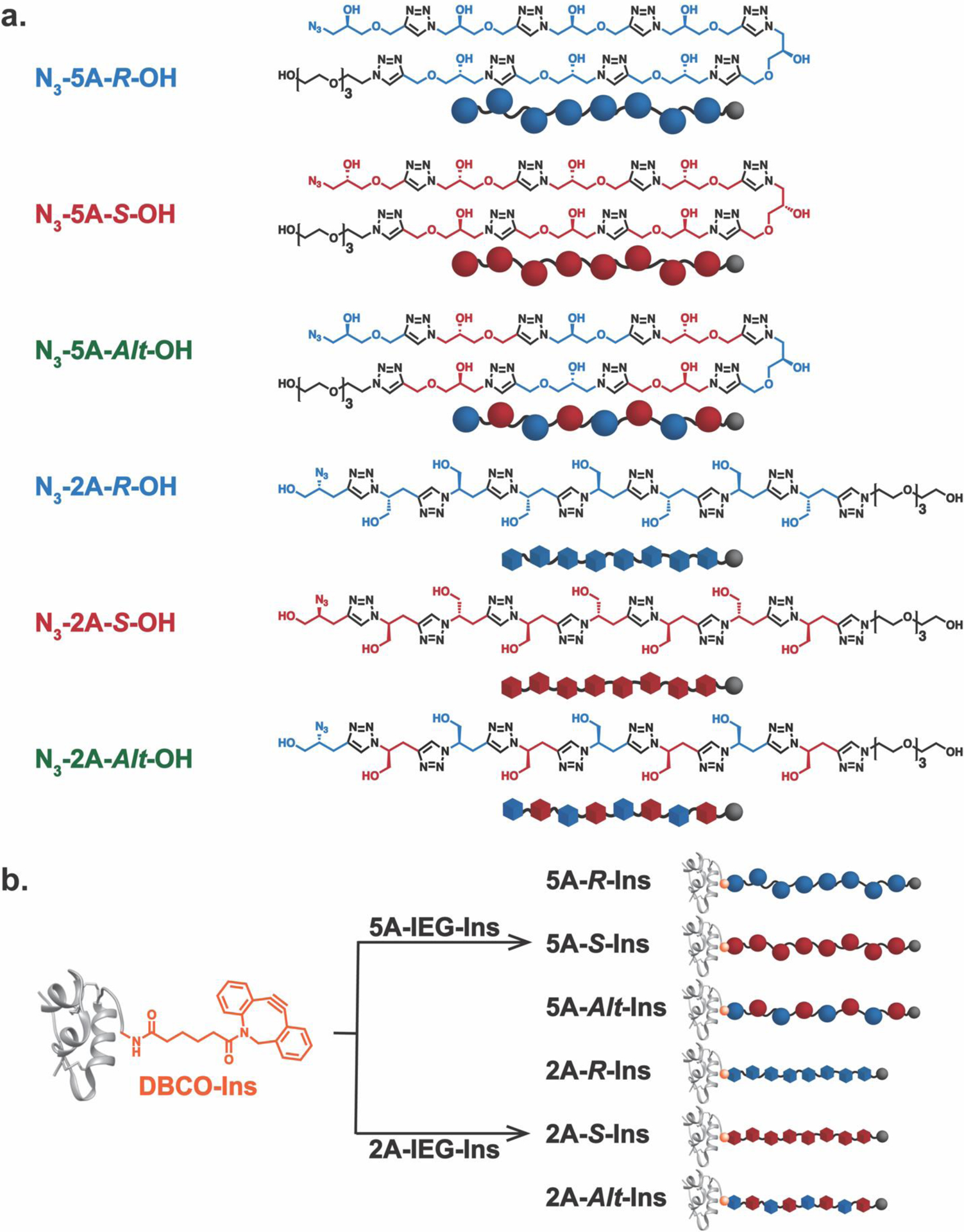

We used IEG24,26,38 to synthesize two sets of discrete polytriazoles with varied absolute configurations. One set possesses 5 atoms between each triazole repeat unit and is referred to herein as “5A”. The other possesses 2 atoms between each triazole and is referred to as “2A”. We previously showed that, due to their reduced rotational degrees of freedom, 2A IEG polymers are significantly more conformationally restricted than their 5A counterparts, preferring to adopt long-lived chiral secondary structures in solution.26 Each 2A and 5A polymer prepared here has 8 stereogenic centers; in addition to synthesizing the all R and all S (“isotactic”) enantiomers of both the 2A and 5A polymers, we also prepared the alternating R-alt-S (“syndiotactic”) diastereomers of each, giving six novel discrete polymers with azide and tetraethylene glycol chain ends for insulin conjugation and enhanced water solubility, respectively (Figure 2a): N3-5A-R-OH, N3-5A-S-OH, N3-5A-Alt-OH, N3-2A-R-OH, N3-2A-S-OH, and N3-2A-Alt-OH. These polymers were fully characterized by NMR spectroscopy (Figure S1–4), mass spectrometry (vide infra), and CD spectroscopy (Figure S5–10). Notably, the CD spectra for aqueous solutions of N3-2A-R-OH and N3-2A-S-OH showed strong, mirror-image absorption features, which supports the tendency of these polymers to form long-lived chiral secondary structures. Interestingly, N3-2A-Alt-OH displayed very little signal, suggesting that alternation of the backbone stereochemical sequence disrupts this structure. Meanwhile, due to their conformational flexibility, the 5A polymers displayed no discernable signals, as observed previously for similar polymers.

Figure 2. Discrete IEG macromolecules and their insulin conjugates.

a. Structures of water-soluble discrete IEG polymers synthesized in this work. Two different backbones, “2A” and “5A”, were leveraged to tune the backbone rigidity while the absolute configurations of each molecule were defined by the monomers employed in the IEG synthesis. The molar masses of each polymer was confirmed by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (see Supporting Information for more detailS): N3-2A-IEG-OH polymers: observed m/z at 1221.89 [M + H]+ (Calcd m/z = 1220.3 [M + H]+); N3-5A-IEG-OH polymers: Observed m/z at 1460.98 [M + H]+ (Calcd m/z = 1460.5 [M + H]+). b. Conjugation of site-specifically modified insulin, DBCO-Ins, and IEG polymers provides a series of discrete IEG-Insulin conjugates.

Synthesis of discrete insulin–polymer conjugates

With this library of azide-terminated IEG polymers in hand (Figure 2a), we pursued site-specific modification of the N-terminus of the insulin chain B following literature precedents.39–41 Exposing insulin to water-soluble linker DBCO-sulfo-NHS ester (1.5 equivalents to insulin) in PBS buffer (pH 7.5) at 4 °C yielded DBCO-Ins in 32% yield after fast protein liquid chromatography (FPLC) purification (Figure S13). MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry confirmed the single modification of DBCO-Ins (Figure S14). LC-MS/MS revealed that conjugation occurred selectively on the amine group of the N-terminus of chain B (Figure S15–S16).

Insulin-polymer conjugates were formed through SPAAC in nearly quantitative yields following FPLC purification by mixing DBCO-Ins (1 equivalent) with each of our azide-terminated IEG polymers as well as 2 kDa and 5 kDa azide-terminated PEG controls (2 equivalents) in PBS buffer (pH 7.5) at 4 °C for 2 hours (Figure 2b). Size exclusion chromatography (SEC) traces of each conjugate showed unimodal peaks (Figure 3a) with elution times that correlated with the relative hydrodynamic volumes of the conjugates; each of the conjugates eluted faster than insulin alone , as expected due to their larger sizes (Figure S17). No differences in elution time were observed for diastereomeric insulin conjugates. MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry revealed the discrete nature of these IEG-insulin conjugates (Figure 3b). By contrast, PEGylated controls PEG-2k-Ins and PEG-5k-Ins each showed a series of peaks due to the dispersity of their PEG chains on MALDI-TOF (Figure 3b). Notably, the discrete IEG-insulin conjugates have similar molar masses to the PEG-2k-Ins conjugate (Figure 3b). These results set the stage for a deeper investigation of how synthetic polymer configuration and composition may impact the structure and properties of insulin conjugates. We do note that SPAAC42–44 is known to give a mixture of regioisomeric triazole products; thus, while we could not determine the ratio of regioisomers in this study, we suspected a ~1:1 mixture45 and assume herein that this variation at the interface between insulin and our polymers has little impact on the overall conjugate properties.

Figure 3. Characterizations of polymer–insulin conjugates.

a. Size exclusion chromatography tracesofpurified insulin conjugates obtained by FPLC (BioRad SEC-70). b. MALDI-TOF mass spectra of purified insulin conjugates: 2A-IEG-Ins diastereomers: observed m/z at 7347.6 [M + H]+ (Calcd m/z = 7345.7 [M+ H]+; 5A-IEG-Ins diastereomers: Observed m/z at 7584.8 [M + H]+; calcd m/z = 7585.9 [M + H]+. c. Circular dichroism spectra of various purified insulin conjugates in PBS buffer (0.15 mg / mL of insulin).

Solution characterization of polymer-insulin conjugate structure

Circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy was used to characterize each polymer-insulin conjugate (Figure 3c). In each case, the spectra were dominated by features observed for native insulin, suggesting that polymer conjugation did not disrupt its secondary structure. The 2A IEG conjugates showed small differences as a function of the IEG polymer stereochemistry; this finding agrees with the fact that the 2A IEG polymers display larger differences on their own on account of their longer-lived secondary structures. As expected, the more conformationally flexible 5A IEG conjugates displayed negligible differences as a function of the polymer configuration. Finally, given the achiral nature of PEG, the PEGylated conjugates showed no differences compared to insulin alone.

Insulin is known to exist in various oligomeric states in solution; tuning this aggregation behavior is a common strategy to optimize the therapeutic performance of insulin derivatives. We investigated the oligomerization states of a subset of our insulin conjugate—5A-R-Ins, 5A-S-Ins, 2A-R-Ins, 2A-S-Ins, and PEG-2k-Ins—at 4 °C using a previously reported DOSY method.41,46,47 The diffusion coefficient (D) of free insulin was observed to be ~1 × 10−6 cm2/s, which suggests a mixture of dimers (reported D = 1.22 × 10−6 cm2/s) and hexamers (reported D = 0.87 × 10−6 cm2/s) based on reported D values (Figure S28). The D values for our polymer-insulin conjugates trended with hydrodynamic size, as expected; however, the results suggest that polymer conjugation has minimal impact on the aggregation state (Figures S29–33). Finally, 5A-S-Ins, 2A-S-Ins, and free insulin displayed similar resistance to trypsin-induced degradation as measured by LC-MS (Figure S34–S36).

In vivo activity of polymer-insulin conjugates in STZ-induced diabetic mice

We used the STZ-induced C57BL/6J diabetic mouse model to evaluate the blood glucose lowering performance of our polymer-insulin conjugates as a function of time. Notably, as these mice cannot produce insulin on their own, any observed changes in blood glucose levels are due to diet and externally supplied insulin or insulin surrogates.32,48–50 Each conjugate along with insulin and commercial Lantus were subcutaneously administered to the mice (n = 3 mice per group) at a dose of 5 IU insulin/kg. Blood glucose levels were measured 1 h, 2 h, and 4 h after administration. Figure 4A plots blood glucose levels versus time grouped by polymer class: 2A IEG-insulin conjugates (red), 5A IEG-insulin conjugates (blue), and PEGylated conjugates (green). Interestingly, all the IEG-insulin conjugates lowered blood glucose levels below a non-diabetic level (200 mg/dL) and maintained effectiveness for at least 2 hours (Figure 4a and S37. 2A-S-Ins, 5A-R-Ins, and 5A-Alt-Ins displayed statistically significant increases in activity one hour after injection compared to the PEGylated conjugates (Figure 4b–c). After two hours, there were no statistically significant differences between the test groups; however, larger differences were observed after 4 hours. In general, mice given the 5A-IEG-Ins conjugates displayed a shorter-term response than the 2A-IEG-Ins conjugates, with higher blood glucose levels after 4 hours. Interestingly, 2A-S-Ins maintained a statistically significant reduction in blood glucose compared to Lantus, 5A-S-Ins, and 5A-Alt-Ins conjugates at this time point (Figure 4d). Altogether, while the underlying mechanisms for these differences could involve a wide range of factors, such as conjugate stability, pharmacokinetics, aggregation state, target affinity, etc., these preliminary results strongly suggest that IEG polymer composition and structure can lead to variations in insulin conjugate performance, which will motivate future designs of precise polymer–protein conjugates.

Figure 4. In vivo blood glucose studies in STZ-induced diabetic C56BL/6J mice (n = 3 mice per treatment group).

a. Blood glucose levels versus time for polymers grouped by composition (e.g., “2A-IEG-Ins” presents the average for 2A-R-Ins, 2A-S-Ins, and 2A-Alt-Ins combined, similarly for 5A-IEG-Ins and PEG-Ins), showing the overall differences in activity compared to commercial Lantus, and insulin alone. (Food was provided after the 4 h data point) b. Blood glucose levels 1 h after treatment with 2A-IEG-Ins diastereomers, PEG-2k-Ins, and PEG-5k-Ins. c. Blood glucose levels 1 h after treatment with 5A-IEG-Ins diastereomers, PEG-2k-Ins, and PEG-5k-Ins. d. Blood glucose levels 4 h after treatment with 5A-IEG-Ins and 2A-IEG-Ins conjugates compared to commercial long-lasting insulin Lantus. The 5A-IEG-Ins conjugates generally lead to a more transient response than the 2A-IEG-Ins conjugates. 2A-S-Ins in particular shows longer-lasting effects than Lantus. (Statistical significance: ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05).

Immunogenicity studies of representative insulin conjugates after long-term repeat dosing

Next, we investigated the potential immunogenicity of 5A-R-Ins, 5A-S-Ins, 2A-R-Ins, 2A-S-Ins, and PEG-2k-Ins in healthy C57BL/6J male mice51 (n = 5) following five doses to determine if these novel conjugates induced systemic inflammation and/or conjugate-specific antibodies.52 The mice were first administered glucose intraperitoneally (1g/kg) to counterbalance the blood glucose lowering effects of the insulin conjugates. The five conjugates along with free insulin and PBS buffer were then dosed subcutaneously at the same levels used for the diabetic mouse study above (5 IU insulin /kg) once per week for 5 consecutive weeks. All the conjugates displayed similar blood glucose lowering effects over the course of this study (Figure S38). Moreover, weekly weight measurements (Figure S39) and complete blood count analyses (Figure S40–47) suggested that the conjugates were well-tolerated.

The mice were sacrificed by cardiac puncture for toxicity and immunogenicity analysis 14 days after the last dose following standard protocols.53–58 Serum liver enzyme levels (Figure S48–51) and liver histology (Figure S52–58) indicated that there was no adverse impact on liver function, which was a reported limitation of the PEGylated insulin,12 following this dosing level and frequency. Meanwhile, measurements of serum immunoglobulins (Figure S59–64), cytokines (Figure S65–74), and anti-insulin antibodies (Figure S75) exhibited no significant differences for the insulin conjugates compared to free insulin.59 Altogether, these results indicate that our IEG-insulin conjugates show no signs of toxicity or immunogenicity following repeat dosing in this model.

3. Conclusion:

In conclusion, we have developed a new approach to manufacture uniform polymer-insulin conjugates. A small library of conjugates that varied by the absolute configurations and conformational flexibilities of their synthetic polymer components was synthesized and characterized, confirming that the conjugates are uniform and that IEG polymer conjugation does not negatively impact the stability of insulin. Moreover, these insulin conjugates displayed configuration and composition-dependent blood glucose lowering performance in a diabetic mouse model, with some displaying faster acting and longer lasting effects than a commercial insulin derivative. Finally, these conjugates were shown to be non-toxic and non-immunogenic in a preclinical mouse model. Further studies of the impacts of IEG polymer length, particularly using longer polymers that may lead to more exaggerated properties differences, as well as backbone and sidechain composition on the properties of discrete biomolecule conjugates are underway in our laboratories. Altogether, this work offers a new conceptual platform for exploring how the molecular details of synthetic polymers may impact the functions of their biopolymer conjugates. Thus, while PEG dominates the landscape of protein-polymer conjugates today, we envision a future where biologic drugs are conjugated to a molecularly-optimized synthetic polymers to achieve maximal properties such as therapeutic index and storage/transportation stability.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Synthetic procedures; instrumentation details; NMR spectra; CD spectroscopy; MALDI-TOF data; DOSY data; in vivo studies of polymer-insulin conjugates.

5. References:

- 1.Leader B, Baca QJ & Golan DE Protein therapeutics: A summary and pharmacological classification. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 7, 21–39 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ekladious I, Colson YL & Grinstaff MW Polymer–drug conjugate therapeutics: advances, insights and prospects. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 18, 273–294 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duncan R The dawning era of polymer therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 2, 347–360 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ko JH & Maynard HD A guide to maximizing the therapeutic potential of protein-polymer conjugates by rational design. Chem. Soc. Rev 47, 8998–9014 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alconcel SNS, Baas AS & Maynard HD FDA-approved poly(ethylene glycol)-protein conjugate drugs. Polym. Chem 2, 1442–1448 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knop K, Hoogenboom R, Fischer D & Schubert US Poly(ethylene glycol) in drug delivery: Pros and cons as well as potential alternatives. Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed 49, 6288–6308 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pelegri-Oday EM, Lin EW & Maynard HD Therapeutic protein-polymer conjugates: Advancing beyond pegylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc 136, 14323–14332 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang J, Li Y, Nie G & Zhao Y Precise design of nanomedicines: Perspectives for cancer treatment. Natl. Sci. Rev 6, 1107–1110 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manzari MT et al. Targeted drug delivery strategies for precision medicines. Nat. Rev. Mater 6, 351–370 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diab A et al. Bempegaldesleukin (NKTR-214) plus nivolumab in patients with advanced solid tumors: Phase I dose-escalation study of safety, effi cacy, and immune activation (PIVOT-02). Cancer Discov. 10, 1158–1173 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Squibb NT-M A Dose Escalation and Cohort Expansion Study of NKTR-214 in Combination With Nivolumab and Other Anti-Cancer Therapies in Patients With Select Advanced Solid Tumors ( PIVOT-02 ). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02983045 (accessed 2022-09-03).

- 12.Muñoz-Garach A, Molina-Vega M & Tinahones FJ How Can a Good Idea Fail? Basal Insulin Peglispro [LY2605541] for the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Ther. 8, 9–22 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen BM, Cheng TL & Roffler SR Polyethylene Glycol Immunogenicity: Theoretical, Clinical, and Practical Aspects of Anti-Polyethylene Glycol Antibodies. ACS Nano 15, 14022–14048 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shatz W et al. Identification and characterization of an octameric PEG-protein conjugate system for intravitreal long-acting delivery to the back of the eye. PLoS One 14, 1–20 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Y, Mesa-Antunez P, Fortuin L, Andrén OCJ & Malkoch M Degradable High Molecular Weight Monodisperse Dendritic Poly(ethylene glycols). Biomacromolecules 21, 4294–4301 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang J et al. Monodisperse and Polydisperse PEGylation of Peptides and Proteins: A Comparative Study. Biomacromolecules 21, 3134–3139 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schellenberger V et al. A recombinant polypeptide extends the in vivo half-life of peptides and proteins in a tunable manner. Nat. Biotechnol 27, 1186–1190 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ding S et al. Multivalent antiviral XTEN-peptide conjugates with long in vivo half-life and enhanced solubility. Bioconjug. Chem 25, 1351–1359 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lutz JF, Lehn JM, Meijer EW & Matyjaszewski K From precision polymers to complex materials and systems. Nat. Rev. Mater 1, 1–14 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aksakal R, Mertens C, Soete M, Badi N & Du Prez F Applications of Discrete Synthetic Macromolecules in Life and Materials Science: Recent and Future Trends. Adv. Sci 8, 1–22 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Genabeek B et al. Properties and applications of precision oligomer materials; where organic and polymer chemistry join forces. J. Polym. Sci 59, 373–403 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Macleod MJ & Johnson JA Block co-polyMOFs: Assembly of polymer-polyMOF hybrids: Via iterative exponential growth and ‘click’ chemistry. Polym. Chem 8, 4488–4493 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gu Y, Huang M, Zhang W, Pearson MA & Johnson JA PolyMOF Nanoparticles: Dual Roles of a Multivalent polyMOF Ligand in Size Control and Surface Functionalization. Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed 58, 16676–16681 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiang Y et al. Iterative Exponential Growth Synthesis and Assembly of Uniform Diblock Copolymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc 138, 9369–9372 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Golder MR et al. Stereochemical sequence dictates unimolecular diblock copolymer assembly. J. Am. Chem. Soc 140, 1596–1599 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nguyen HVT et al. Bottlebrush polymers with flexible enantiomeric side chains display differential biological properties. Nat. Chem 14, 85–93 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu L et al. Enantiomer-dependent immunological response to chiral nanoparticles. Nature 601, 366–373 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.New WHO report maps barriers to insulin availability and suggests actions to promote universal access. Saudi medical journal 42, 1374–1375 (2021). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bhatnagar S, Srivastava D, Jayadev MSK & Dubey AK Molecular variants and derivatives of insulin for improved glycemic control in diabetes. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol 91, 199–228 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McKeage K & Goa KL Insulin glargine: a review of its therapeutic use as a long-acting agent for the management of type 1 and 2 diabetes mellitus. Drugs 61, 1594–624 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koivisto VA The human insulin analogue insulin lispro. Ann. Med 30, 260–266 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chou DHC et al. Glucose-responsive insulin activity by covalent modification with aliphatic phenylboronic acid conjugates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 112, 2401–2406 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mansfield KM & Maynard HD Site-Specific Insulin-Trehalose Glycopolymer Conjugate by Grafting from Strategy Improves Bioactivity. ACS Macro Lett. 7, 324–329 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bakh NA et al. Glucose-responsive insulin by molecular and physical design. Nat. Chem 9, 937–943 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maikawa CL et al. A co-formulation of supramolecularly stabilized insulin and pramlintide enhances mealtime glucagon suppression in diabetic pigs. Nat. Biomed. Eng 4, 507–517 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maikawa CL et al. Ultra-Fast Insulin–Pramlintide Co-Formulation for Improved Glucose Management in Diabetic Rats. Adv. Sci 8, 1–9 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arnaud CH Insulin’s second century. C&EN 100, 26–31 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barnes JC et al. Iterative exponential growth of stereo- and sequence-controlled polymers. Nat. Chem 7, 810–815 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gao J, Mrksich M, Whitesides GM & Gomez FA Using Capillary Electrophoresis To Follow the Acetylation of the Amino Groups of Insulin and To Estimate Their Basicities. Anal. Chem 67, 3093–3100 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.BRADBURY JH & BROWN LR Nuclear‐Magnetic‐Resonance‐Spectroscopic Studies of the Amino Groups of Insulin. Eur. J. Biochem 76, 573–582 (1977). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Østergaard M, Mishra NK & Jensen KJ The ABC of Insulin: The Organic Chemistry of a Small Protein. Chem. - A Eur. J 26, 8341–8357 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kiick KL, Saxon E, Tirrell DA & Bertozzi CR Incorporation of azides into recombinant proteins for chemoselective modification by the Staudinger ligation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 99, 19–24 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Agard NJ, Prescher JA & Bertozzi CR A strain-promoted [3 + 2] azide-alkyne cycloaddition for covalent modification of biomolecules in living systems. J. Am. Chem. Soc 126, 15046–15047 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jewett JC, Sletten EM & Bertozzi CR Rapid Cu-free click chemistry with readily synthesized biarylazacyclooctynones. J. Am. Chem. Soc 132, 3688–3690 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Erickson PW, Fulcher JM, Spaltenstein P & Kay MS Traceless Click-Assisted Native Chemical Ligation Enabled by Protecting Dibenzocyclooctyne from Acid-Mediated Rearrangement with Copper(I). Bioconjug. Chem 32, 2233–2244 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mann JL et al. An ultrafast insulin formulation enabled by high-throughput screening of engineered polymeric excipients. Sci. Transl. Med 12, 1–12 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Patil SM, Keire DA & Chen K Comparison of NMR and Dynamic Light Scattering for Measuring Diffusion Coefficients of Formulated Insulin: Implications for Particle Size Distribution Measurements in Drug Products. AAPS J. 19, 1760–1766 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Furman BL Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Models in Mice and Rats. Curr. Protoc. Pharmacol 70, 5.47.1–5.47.20 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gu Z et al. Injectable nano-network for glucose-mediated insulin delivery. ACS Nano 7, 4194–4201 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yu J et al. Glucose-responsive insulin patch for the regulation of blood glucose in mice and minipigs. Nat. Biomed. Eng 4, 499–506 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jiskoot W et al. Mouse Models for Assessing Protein Immunogenicity: Lessons and Challenges. J. Pharm. Sci 105, 1567–1575 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bennett B, Check IJ, Olsen MR & Hunter RL A comparison of commercially available adjuvants for use in research. J. Immunol. Methods 153, 31–40 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Elsabahy M & Wooley KL Cytokines as biomarkers of nanoparticle immunotoxicity. Chem. Soc. Rev 42, 5552–5576 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang D et al. [Gd@C82(OH)22]n nanoparticles induce dendritic cell maturation and activate Th1 immune responses. ACS Nano 4, 1178–1186 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Baker MP, Reynolds HM, Lumicisi B & Bryson CJ Immunogenicity of protein therapeutics: The key causes, consequences and challenges. Self/Nonself - Immune Recognit. Signal 1, 314–322 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Products TP Guidance for industry: Immunogenicity assessment for therapeutic protein products [excerpts]. Biotechnol. Law Rep 32, 172–185 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yadav M et al. Predicting immunogenic tumour mutations by combining mass spectrometry and exome sequencing. Nature 515, 572–576 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shalapour S et al. Immunosuppressive plasma cells impede T-cell-dependent immunogenic chemotherapy. Nature 521, 94–98 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fineberg SE et al. Immunological responses to exogenous insulin. Endocr. Rev 28, 625–652 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.