Abstract

An effective cancer therapy requires both killing cancer cells and targeting tumor-promoting pathways or cell populations within the tumor microenvironment (TME). We purposely search for molecules that are critical for multiple tumor-promoting cell types and identified nuclear receptor subfamily 4 group A member 1 (NR4A1) as one such molecule. NR4A1 has been shown to promote the aggressiveness of cancer cells and maintain the immune suppressive TME. Using genetic and pharmacological approaches, we establish NR4A1 as a valid therapeutic target for cancer therapy. Importantly, we have developed the first-of-its kind proteolysis-targeting chimera (PROTAC, named NR-V04) against NR4A1. NR-V04 effectively degrades NR4A1 within hours of treatment in vitro and sustains for at least 4 days in vivo, exhibiting long-lasting NR4A1-degradation in tumors and an excellent safety profile. NR-V04 leads to robust tumor inhibition and sometimes eradication of established melanoma tumors. At the mechanistic level, we have identified an unexpected novel mechanism via significant induction of tumor-infiltrating (TI) B cells as well as an inhibition of monocytic myeloid derived suppressor cells (m-MDSC), two clinically relevant immune cell populations in human melanomas. Overall, NR-V04-mediated NR4A1 degradation holds promise for enhancing anti-cancer immune responses and offers a new avenue for treating various types of cancer.

Keywords: NR4A1, PROTAC degrader, immune modulation, cancer immunotherapy, melanoma

Introduction

The tumor microenvironment (TME) consists of many cell types that cooperatively promote tumor development and progression. Most cancer therapeutics are designed to target one molecule in one defined cell type. For example, vemurafenib (BRAF inhibitor) inhibits melanoma through targeting mutated BRAF; whereas pembrolizumab (anti-PD-1 antibody) blocks the immune checkpoint PD-1 on T cells to increase anti-tumor immunity. Several FDA-approved combinations therapies involve cancer cell-killing chemotherapies and immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) to activate anti-cancer immunity within the TME, suggesting that co-targeting cancer cells and other cell types within the TME can be effective therapeutic regimens for cancer.

The current research focus is NR4A1, an intracellular transcription factor that is known for its crucial role not only in immune regulations but also in many other functions1–4. Specifically, within the TME, NR4A1 is known to act on several cell types: 1) NR4A1 is involved in angiogenesis in the B16 melanoma model5. The impact of NR4A1 on neoangiogenesis has also been confirmed in several other tumor models6–9. As neoangiogenesis in tumors induces the formation of new blood vessels with increased permeability, NR4A1 plays a critical role in regulating basal vascular permeability by increasing endothelial nitric-oxide synthase and downregulating several junction proteins involved in adherens junctions and tight junctions10; 2) NR4A family has been shown to be elevated in exhausted CD8+ T cells, and their deletion rescues the cytotoxicity function of CD8+ T cell during tumorigenesis1, 11; 3) Tumor-infiltrating regulatory T cells (TI-Tregs) rely on NR4A1 and its other family members for their immune suppressive function4, 12; 4) NR4A1 can be induced in natural killer (TI-NK) cells through the IFN-γ/p-STAT1/IRF1 signaling pathway, which leads to diminished NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity against hepatocellular carcinoma13. Under physiological conditions, NR4A1 exerts crucial regulatory functions in B cells, limiting their expansion in response to antigen stimulation the absence of secondary signals and constraining the survival of self-reactive B cells in peripheral tissues3. B cells have been increasingly recognized for their important role in cancer, with studies indicating a correlation between B cell presence in the TME and improved prognosis and sensitivity to ICIs14. While the specific impact of NR4A1 on TI-B cells remains unexplored, the involvement of NR4A1 in modulating B cell responses underscores its potential as a therapeutic target for harnessing the anti-tumor functions of B cells in the TME.

Celastrol, a triterpenoid quinine methide derived from the root of Tripterygium wilfordii15, has been shown to covalently bind to NR4A1 and possesses anti-inflammatory properties16–18.

Celastrol is not an ideal candidate for clinical development due to limitations such as low bioavailability, a narrow therapeutic window, and undesired adverse effects19. Nevertheless, the moderate binding affinity of celastrol to NR4A1 (Kd of 0.29 μM)20 makes it a promising starting point as a warhead for the design and synthesis of NR4A1 proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs). PROTACs are bifunctional molecules that consist of a pharmacophore targeting a protein of interest and another pharmacophore recruiting an E3 ligase such as von Hippel Lindau (VHL) or cereblon (CRBN), facilitating polyubiquitination and subsequent proteasome degradation of the target protein21, 22. PROTAC represents a novel approach in drug discovery. Unlike the conventional “occupancy-driven” inhibitor-based therapy, PROTACs work in a catalytic and “event-driven” manner, leading to the depletion of protein targets. This unique mechanism of action offers several advantages including higher potency, prolonged pharmacological effect, and improved selectivity. More importantly, PROTACs offer new possibilities to target traditionally undruggable or difficult-to-drug targets, such as transcriptional factors, scaffolding proteins, and multi-functional proteins that cannot be effectively inhibited by a single inhibitor.

Here, we report a first-of-its-kind NR4A1-targeting PROTAC named NR-V04 as a lead for cancer therapy. We have performed extensive characterization of NR-V04, which reveals its promising pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profile, degradation efficiency and specificity for NR4A1, tumor-inhibitory effect and immune activation within the TME, along with its low toxicity within the therapeutic dosing range.

Results

NR4A1 is elevated in many cell types within the TME of human cancers and is a valid target in the TME for cancer therapy.

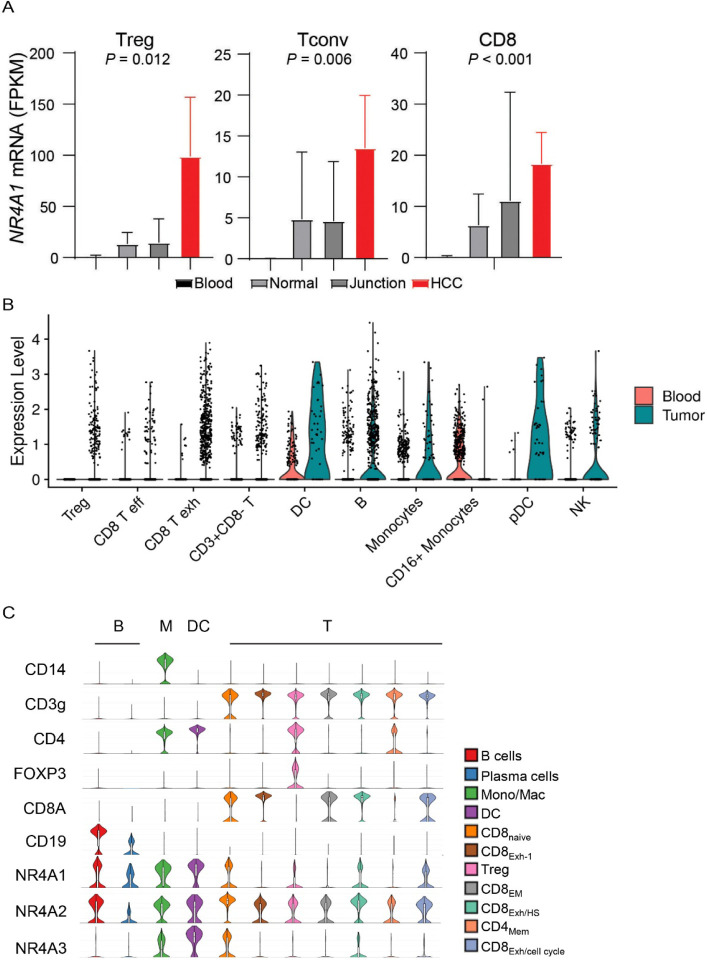

We recently found that NR4A1 is the most elevated gene in the TI-Tregs from human renal clear cell carcinoma (RCC, GEO: GSE121638)23. We further analyzed NR4A1 expression within several single-cell RNA sequencing datasets (scRNAseq), including human hepatocellular carcinomas (HCC, GEO: GSE98638)24 and melanomas (GEO: GSE120575)25. In HCC, we confirmed that NR4A1 expression was significantly elevated in TI-Tregs relative to Tregs from blood or normal tissues, conventional CD4+ T cells (Tconv), or CD8+ T cells (Fig. 1A, note the difference in FPKM scales). Exhausted Tconv or CD8+ T cells also had increased levels of NR4A1, though at much lower levels than that in TI-Tregs (Fig. 1A). In melanoma, there is diverse expression pattern of NR4A1 across multiple cell types within the TME, but most TI immune cell types showed elevated NR4A1 expression than their blood counterparts (Fig. 1B). NR4A1 expression was particularly evident in B cells, monocytes or macrophages (M), dendritic cells (DCs), Treg cells, and exhausted CD8+ T (Texh) cells (Fig. 1C)25. NR4A2 displayed a ubiquitous presence across all immune cell populations, while NR4A3 predominantly appeared in monocytes or macrophages, DCs, and a specific subset of CD8 T cells (Fig. 1C). Leveraging the TCGA datasets, we investigated NR4A1 expression in melanoma patients and identified a negative correlation between NR4A1 and anti-tumor immune responses, including the gene expression of IFNγ (interferon γ), GZMB (granzyme B), and PRF1 (perforin) (Supplementary Fig. 1A–1C). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) revealed that NR4A1 expression was inversely associated with T cell receptor (TCR) and B cell receptor (BCR) signaling pathways (Supplementary Fig. 1D–1G). Collectively, these findings highlight the potential involvement of NR4A1 in the immune modulation of human cancers.

Figure 1.

NR4A1 is elevated in several tumor-promoting immune cells within the tumor microenvironment. A. Expression of NR4A1 in T cells from blood, normal parenchyma, adjacent normal junction, or human hepatocellular carcinomas (HCC, GSE98638). B. Violin plots showing NR4A1 expression in different immune cells from human blood or melanomas. C. Violin plots showing gene expression including NR4A family and lineage markers in human melanomas (GSE120575).

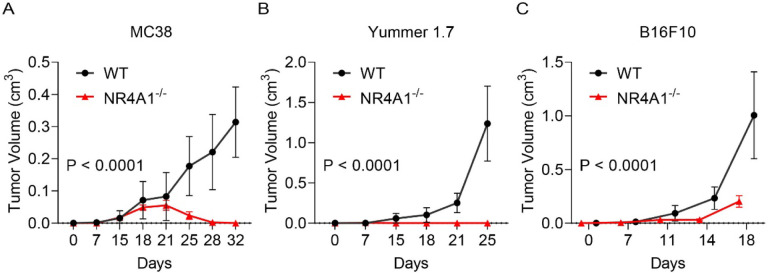

To determine whether NR4A1 plays important roles in the TME, we implanted 3 syngeneic tumors into wild-type (WT) or NR4A1−/− (KO) mice, including MC38 colon cancer model, Yummer1.7 and B16F10 melanoma models. We used a minimal number of tumor cells that can produce tumors in WT mice and found that NR4A1−/− (KO) mice exhibited much slower tumor growth rate in all of the tumor models (Fig. 2A–2C). MC38 model showed very minimal tumor growth that peaked at the 3rd week in the KO mice but was regressed thereafter (Fig. 2A), suggesting that tumors be eradicated by the induction of anti-tumor immunity in KO mice. These data strongly support the role of NR4A1 in the TME and immune modulation, and suggest that targeting NR4A1 is a potentially promising immunotherapy for cancer.

Figure 2.

NR4A1-deletion leads to diminished tumor growth. A-C. Primary tumor growth curve in littermates of wild type (WT) or NR4A1−/− mice, including (A) MC38 colon cancer, (B) Yummer1.7 melanoma and (C)B16F10 melanoma. n = 7–8 mice per group.

The design and screening of PROTACs against NR4A1.

A number of NR4A1 ligands have been reported26, and celastrol is one of the few that has been well characterized. Celastrol covalently binds to NR4A1 through engaging cysteine C551, and the binding affinity is within the sub-nanomolar range based on several biophysical assays16–18. The structure and activity relationship (SAR) study of celastrol on NR4A1 has been explored, which indicates that the carboxylic acid group of celastrol is amenable for chemical modifications17. Therefore, we reasoned that celastrol might be a suitable warhead for PROTAC construction. We performed a molecular docking study between celastrol and the ligand binding domain (LBD) of NR4A1 and found that the carboxylic acid group is solvent-exposed, which represents an ideal tethering site for linker attachment (Fig. 3A). We utilized polyethylene glycol (PEG) linkers for the conjugation of celastrol to a VHL E3 ligase ligand via two amide bonds. As a proof-of-concept study, three PROTACs with different PEG linker lengths were synthesized (Fig. 3B) and tested in CHL-1 human melanoma cells (Fig. 3C–3D). Celastrol treatment did not alter the protein level of NR4A1 (Fig. 3C–3D). NR-V04 – which bears a 4-PEG linker, exhibited the highest potency in reducing the protein level of NR4A1 (Fig. 3C–3D) and was thus chosen for further investigations.

Figure 3.

The design and synthesis of NR4A1 PROTACs. A. Docking study revealed the carboxylic acid in celastrol is a potential tethering vector for PROTAC construction. B. The structure of synthesized PROTACs. C-D. The initial screening of NR4A1 degradation in CHL-1, a human melanoma cell line. CHL-1 cells were treated with 250 nM PROTACs for 16 hours and the degradation was determined by (C) immunoblotting and (D) densitometry. n=2.

NR-V04 efficiently reduces NR4A1 protein level.

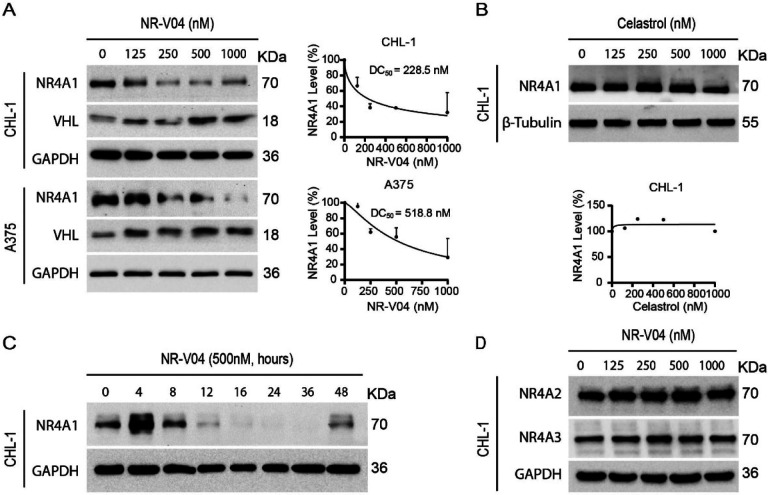

Following a 16-hr treatment, NR-V04 induced a dose-dependent decrease of NR4A1 protein in CHL-1 cells with a 50% degradation concentration (DC50) of 228.5 nM and A375 melanoma cells with a DC50 of 518.8 nM (Fig. 4A). NR-V04 treatment also reduced NR4A1 protein level in WM164 and M229 human melanoma cells (Supplementary Fig. 2A), and SM1 and SW1 – two mouse melanoma cell lines (Supplementary Fig. 2B). Celastrol did not change NR4A1 protein level (Fig. 4B). Notably, NR-V04 treatment led to accumulation of the VHL protein (Fig. 4A and Supplementary Fig. 2A). Time course studies indicated that the efficient reduction of NR4A1 occurred between 8–48 hrs after NR-V04 treatment (Fig. 4C). Interestingly, we observed an initial induction of NR4A1 protein after 4 hrs of NR-V04 treatment (Fig. 4C), along the timeline of increased NR4A1 mRNA after 4 hrs of NR-V04 treatment (Supplementary Fig. 3). We reasoned that this induction should be mainly caused by celastrol, because we observed an increase in NR4A1 mRNA levels after 2 hrs of celastrol treatment (Supplementary Fig. 3). Among the three NR4A family members, NR-V04 selectively reduced the NR4A1 protein level while sparing NR4A2 and NR4A3 (Fig. 4D, Supplementary Fig. 2C). Our data support that NR-V04 is an effective NR4A1 degrader in vitro.

Figure 4.

NR-V04 induces NR4A1 degradation. A. NR-V04 effectively promoted the degradation of NR4A1 in two human melanoma cell lines in 16 hours, CHL-1 (DC50 = 228.5 nM) and A375 (DC50 = 518.8 nM), while simultaneously stabilizing VHL protein. B. Celastrol treatment did not result in any significant change in the expression level of NR4A1 in the CHL-1 cell line in 16 hours. C. Time-dependent degradation of NR4A1. CHL-1 cells were treated with 500nM of NR-V04 at the indicated time points. D. NR-V04 did not induce the degradation of NR4A2 and NR4A3. A-D: n=2.

NR-V04 induces ternary complex formation and proteasome-mediated NR4A1 degradation.

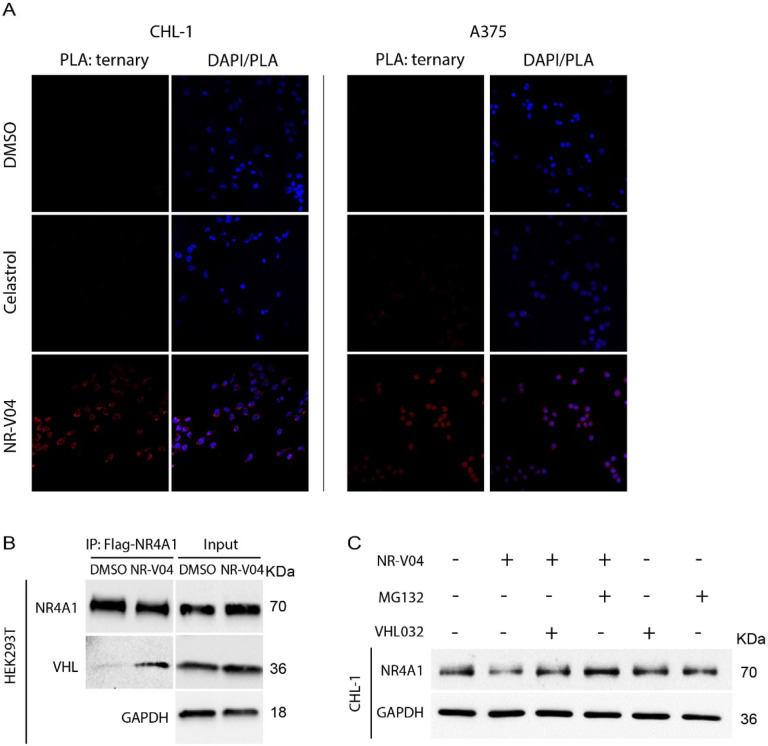

Ternary complex formation is a prerequisite for PROTAC to mediate protein degradation22. We employed proximity ligation assays (PLA) to detect localized signals only when NR4A1 and VHL are in close proximity with the presence of NR-V04. NR-V04 treatment induced very strong PLA signals but not when cells were treated with celastrol or DMSO (Fig. 5A, Supplementary Fig. 4A). Additionally, we conducted co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) experiment using Flag-NR4A1 expressed in the HEK293T cells with and without NR-V04 treatment. Notably, NR-V04 treatment led to the formation of a complex between NR4A1 and VHL, which was not observed with DMSO-treated cells (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5. NR-V04 induces a ternary complex formation and mediates NR4A1 degradation through the ubiquitin-proteasome system.

A. Proximity Ligation Assay (PLA) showing ternary complex formation induced by NR-V04. CHL-1 (left panels) and A375 (right panels) cells were treated with DMSO, 500 nM Celastrol, or 500 nM NR-V04 for 16 hrs. Representative images were shown for PLA assay (20 x magnification). B. Co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) experiment showing complex formation between NR4A1 and VHL by NR-V04 treatment. Co-IP was performed in NR4A1-Flag overexpressed HEK293T cells that were pretreated with 0.5 μM MG132 for 10 minutes, followed by 16-hour treatment with DMSO or 500 nM NR-V04. NR4A1 was pulled down using an anti-Flag antibody conjugated to magnetic beads. C. NR-V04 induces NR4A1 degradation via VHL E3 ligase- and proteasome-dependent manner. CHL-1 cells were pretreated with 0.5 μM MG132 or 10 μM VHL 032 for 10 minutes, followed by 16-hour treatment with DMSO or 500 nM NR-V04. A-C: n=2.

We further determined the mechanism of action (MOA) of NR-V04-mediated reduction of NR4A1 protein. MG132, a proteasome inhibitor, effectively rescued NR4A1 protein level reduced by NR-V04 (Fig. 5C), which supports that NR-V04-induced reduction of NR4A1 protein is through the proteasome pathway. VHL-032, the VHL ligand used for NR-V04 construction, prevented the NR-V04-induced degradation of NR4A1 ( Fig. 5C ), which is further supported using the VHL-knockout cells (Supplementary Fig. 4B).

NR-V04 has good pharmacokinetic (PK) property and shows prolonged NR4A1 degradation in vivo.

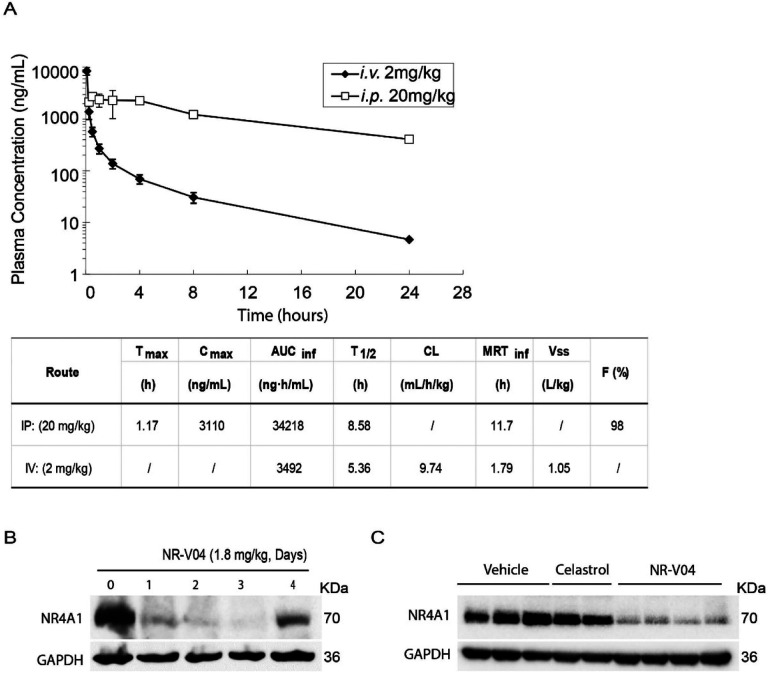

Our mouse study showed that NR-V04 had a half-life of 8.6 hrs via intraperitoneal injections (i.p.) injection and 5.36 hrs via the i.v. injection and near complete absorption (F=98%) through i.p. administration with a low clearance rate (Fig. 6A). Encouraged by the PK result, we assessed the in vivo pharmacodynamic properties (PD) of NR-V04. Mice bearing MC38 tumors were administered two effective doses of NR-V04 (1.8 mg/kg as determined by a pilot dose-dependent experiment, data not shown), and the tumor tissues were collected and analyzed 1 to 4 days after the last treatment. NR-V04 treatment led to significant degradation of NR4A1 starting from day 1, and persisted for 3 days, with a slight recovery of NR4A1 on day 4 (Fig. 6B). Based on the PD result, the dose regimen was set at 1.8 mg/kg, twice a week for following tumor studies. We also analyzed NR4A1 protein in MC38 tumors with mice treated with vehicle, celastrol and NR-V04 after a total of 8 doses for 4 weeks in tumor-bearing mice. The data showed that NR4A1 was almost completely degraded in the NR-V04-treated group, but not in the celastrol- or vehicle-treated group (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6. The pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) study of NR-V04.

A. PK parameters of NR-V04 in WT mice. n = 3. B. NR-V04 induces long-lasting degradation of NR4A1 in MC38 tumors. Mice bearing MC38 tumors were treated with two-dose administration of NR-V04 via i.p. injection at 1.8 mg/kg, and tumors were collected at indicated timepoints. Tumor lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting with each lane representing an individual tumor lysate. n=2 C. Immunoblotting showing NR4A1 degradation in MC38 tumors upon termination. MC38 tumor-bearing mice were treated with vehicle, 1.8 mg/kg NR-V04 or 0.75 mg/kg celastrol treatment (equivalent to 1.67 μmol/kg), every 4 days until experimental end points. Tumor tissues were collected for lysate collection and immunoblotting (n = 4).

NR-V04 inhibits tumor growth.

Based on the PK and PD data, we conducted iterative optimization of NR-V04 treatment in tumor-bearing mice. Our final treatment regimen was set at a dose of 1.8 mg/kg NR-V04 or 0.75 mg/kg celastrol (equivalent to 1.67 μmol/kg) via the i.p. routes, administered twice a week. Treatment was initiated 7 days after inoculation of cancer cells when tumors were palpable. NR-V04 treatment effectively inhibited tumor growth in MC38 model (Fig. 7A) and Yummer1.7 melanoma generated from a tumor formed in a BrafV600/Cdkn2a−/−/Pten−/− mouse (Fig. 7B), as well as the most commonly used B16F10 melanoma model (Fig. 7C). In contrast, celastrol treatment resulted in either increased growth of B16F10 tumors (Supplementary Fig. 5A) or failed to inhibit tumor growth of MC38 tumors (Supplementary Fig. 5B). To validate NR4A1 as the primary molecular target of NR-V04 in the TME, we inoculated B16F10 melanoma tumors in NR4A1−/− mice and found that NR-V04 failed to inhibit B16F10 in these mice (Fig. 7D). Nod/Scid/Il2rg−/− (NSG) mice lack T cells, B cells, and NK cells and NR-V04 treatment failed to inhibit tumor growth in the NSG hosts for MC38 or B16F10 tumors (Fig. 7E–7F).

Figure 7. NR-V04 exhibits outstanding anti-tumor effects in several tumor models.

A-F. Tumor-bearing mice were treated with 1.8 mg/kg NR-V04 or vehicle via i.p. injection on day 7 when tumors were palpable. The treatment was repeated every four days until the tumors reached the endpoint size of 2 cm in diameter. (A) NR-V04 inhibited MC38 colon adenocarcinoma growth, n=4 per group; (B) NR-V04 inhibited Yummer 1.7 melanoma growth, n=4 per group. (C) NR-V04 inhibited B16F10 melanoma growth, n=5 per group. (D) NR-V04 failed to inhibit B16F10 melanoma growth in NR4A1−/− mice, n=5 per group. (E) NR-V04 failed to inhibit MC38 colon adenocarcinoma growth in NSG mice, n=4. (F) NR-V04 failed to inhibit B16F10 melanoma in NSG mice, n=5. Two-way ANOVA was performed for all tumor growth curves with P values indicated.

NR-V04 modulates different immune responses within the TME.

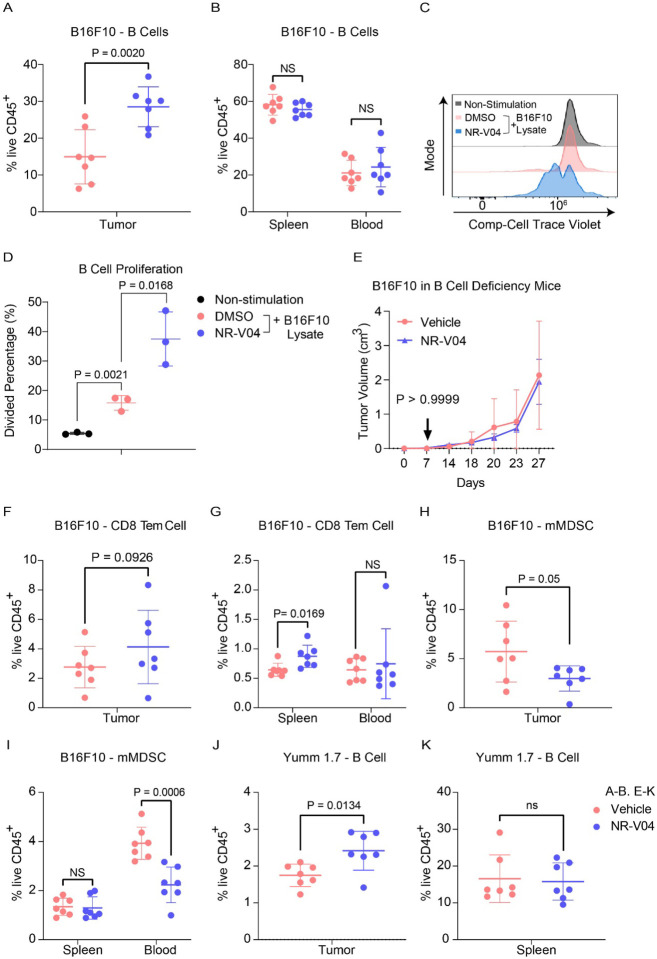

As we were aiming to understand the immune regulatory effects of NR-V04, we designed studies to minimize the influence of tumor size on the tumor immune microenvironment. We allowed tumors to grow to 1 cm in diameter and treated tumor-bearing mice with 2 doses of NR-V04 at similar dose/time intervals (on day 1 and day 4). Tumors were collected on day 7. In the B16F10 model, NR-V04 significantly increased TI-B cells (Fig. 8A showing B220+ cells from 14.7% to 30.1% and gating scheme shown in Supplementary Fig. 6), whereas no significant change was observed in the spleen and blood. Furthermore, we identified the increased portion as CD38+CD138− plasmablasts, and the BCR isotypes are either IgD+IgM− or IgD+IgM+ (Supplementary Fig. 7A–7B).

Figure 8. Effect of NR-V04 on immune cells in the TME. A-B and E-K.

Tumor-bearing mice were treated with 1.8 mg/kg NR-V04 or vehicle via i.p. injection when tumor size reached 1 cm in diameter, with two treatments started as day 1 and repeated on day 4. Tumors were collected and single cells were isolated from tissues for flow cytometry analysis. A-B. NR-V04 treatment increases B cell percentage in the TME, but not in spleen and blood in mice inoculated with B16F10 melanoma, n=7. C-D. NR4A1 depletion induces B cell proliferation. B cells isolated from spleen were labeled with cell trace violet, untreated or treated with B16F10 lysis, following with the cotreatment of DMSO or 500 nM NR-V04 for 24 hours (n=3). B cell proliferation was determined by flow cytometry. E. NR-V04 fails to inhibit B16F10 melanoma growth in mice deficient of mature B cells (n=5). F-G. NR-V04 treatment increased effector memory CD8 T cell percentage in spleen, but not in tumors and blood in B16F10 melanoma (n=7). H-I. NR-V04 treatment decreased mMDSC percentage in tumor and blood, but not in spleen in B16F10 melanoma, n=7. J-K. NR-V04 treatment increased B cell percentage in the TME, but not in spleen and blood in Yumm 1.7 melanoma (n=7). E. Two-way ANOVA was performed for the tumor growth curve with P values indicated. Others are shown as the mean ± SD. A two-sided unpaired t test was performed, with P values indicated.

B cells from the spleen of NR4A1−/− mice exhibited increased proliferation (72.8%) compared to those from WT mice (35.2%) upon 10 μg/mL anti-IgM stimulation (Supplementary Fig. 8A–8B), in agreement with published literature showing that NR4A1 is involved in limiting B cell proliferation3. Since there is no report related to NR4A1 in TI-B cells, we treated WT B cells with B16F10 lysates to induce B cell proliferation, with or without NR-V04 treatment. NR-V04 led to NR4A1 degradation in B cells (Supplementary Fig. 8C–8D) and significantly increased B cell proliferation (Fig. 8C–8D). We inoculated B16F10 into B6.129S2-Ighmtm1Cgn/J strain mice that lack mature B cells and found that NR-V04 was unable to inhibit tumor growth (Fig. 8E), supporting that the tumor inhibitory function of NR-V04 is mediated through B cell elevation in the TME.

We also observed significant increases in memory effector CD8 T cells (CD44+CD62L− Tem, Fig. 8F–8G) in the spleen and a decrease in myeloid-derived monocytic suppressor cells (mMDSC, CD11B+Ly6C+, Fig. 8H–8I) in the blood upon NR-V04 treatment.

We investigated the immune profile in the Yumm1.7 tumor model, known for its human-relevant genetic mutations in melanoma cancer, including BrafV600E/wt/Pten−/−/Cdkn2−/−27. NR-V04 treatment also resulted in a significant increase in the TI-B cells (Fig. 8J–K), supporting a general mechanism of action for NR-V04 in TI-B cell proliferation and induction.

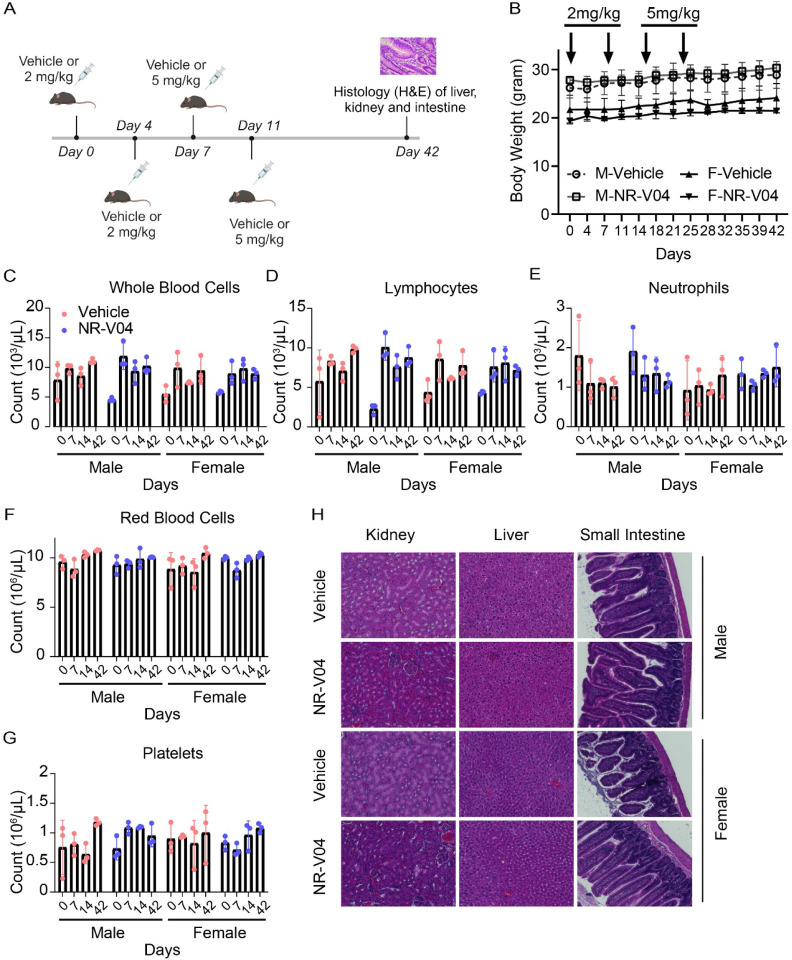

NR-V04 exhibits an excellent safety profile in mice.

Using tumor-bearing mice (Fig. 9), NR-V04 did not significantly induce body weight changes, nor did it induce significant changes in peripheral blood or spleen (Fig. 9). We further assessed the toxicity of NR-V04 using both male and female C57BL/6J mice with increased doses up to 5 mg/kg (Fig. 9A); there were no significant change in body weight (Fig. 9B). Complete blood counts (CBC) were determined at different time points afterNR-V04 treatment that did not result in any significant changes of the hematology parameters, including whole blood cell count (Fig. 9C), lymphocytes (Fig. 9D), neutrophils (Fig. 9E), red blood cells (Fig. 9F), platelets (Fig. 9G), mean platelet volume, mean corpuscular volume, hemoglobin concentration, mean corpuscular hemoglobin, hematocrit percentage, and mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (Supplementary Fig. 9A–9F).

Figure 9. NR-V04 has minimal toxicity.

A. Schematic of the toxicity testing. Male and female mice were treated with two doses of 2 mg/kg NR-V04 and two doses of 5 mg/kg NR-V04 over two weeks. Blood samples were collected on day 0, 7, 14, and 42 for hematology analysis, and body weight was measured twice per week. After day 42, all mice were euthanized, and tissues (kidney, liver, and small intestine) were harvested for H&E staining (n=3). B. Mice did not experience significant weight loss with NR-V04 treatment during the 42-day period. C-G. Hematology analysis of different blood cell components after NR-V04 or vehicle treatment, including (C) whole blood cells, (D) lymphocytes, (E) neutrophils, (F) red blood cells, and (G) platelets. H. NR-V04 impacts on tissue histology, including representative kidney, liver, and small intestine.

Furthermore, we conducted a histological examination using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining to evaluate the kidney, liver, and small intestine tissues in both male and female mice at day 42. Notably, NR-V04 treatment did not induce tissue damage in any of these organs (Fig. 9H). These findings provide important insights into the potential clinical application of NR-V04 as a safe and effective immunotherapeutic agent.

Discussion

In this study, we successfully developed NR-V04, a PROTAC that efficiently degrades NR4A1 in the TME. NR-V04 has strong anti-tumor effects via targeting various cell types, including T cells, B cells, and MDSCs. Though the cancer cell-intrinsic roles of NR4A1 have been extensively characterized in previous studies28–30, our current study strongly supports that NR4A1 plays critical roles in immune modulation within the TME. As such, we have established NR4A1 as a valid target for cancer immunotherapy.

We have discussed several potential cellular targets by NR4A1 degradation, including T cells, NK cells, and endothelial cells etc., but we hadn’t expected TI-B cells to be the most significantly induced cell type by NR-V04 treatment. The role of B cells within the TME is complex and has been debated depending on cancer types, B cell subpopulations, and/or the contrasting functions of TI-B cells. On the one hand, higher B cell numbers – often associated with the tertiary lymphoid structures (TLS), are associated with favorable clinical outcomes and improved responsiveness to immunotherapies in melanoma31, 32; on the other hand, regulatory B (Breg) cells can mediate immunosuppression, and certain B cell subpopulations can promote tumor growth through pro-inflammatory mechanisms33, 34. In our study, NR-V04 significantly increased B cell numbers in B16F10 and Yumm 1.7 mouse melanoma models, and B cell deficiency completely abolishes the tumor inhibitory effect of NR-V04. The importance of B cells in dampening B16F10 melanoma growth has been supported by previous research35, further underscoring the significance of NR-V04-mediated B cell activation. We investigated the mechanistic underpinnings of NR-V04’s impact on B cells and found that NR4A1 expression limits B cell responsiveness to tumor antigens, in agreement with a previous study3. B cells play two critical roles during tumor development: 1) secreting antibodies targeting specific tumor antigens36–40 and 2) presenting tumor antigens to activate the T cell response41–44. With NR-V04 treatment, we observed an increase in the B cell population that primarily consists of plasmablasts, a subset of B cells known for their rapid production and early antibody responses to tumor antigens45. This increase in plasmablasts is associated with a favorable prognosis and has been observed within tumors31. Additionally, NR-V04 treatment enhances the expression of both BCR isotypes, IgD+IgM− and IgD+IgM+, suggesting an enhanced B cell response to tumor antigens. An additional advantage of NR-V04’s B cell regulation is its selective impact on the TME, sparing the B cells or other immune cells in the spleen and blood. This minimizes potential side effects, such as autoimmune responses triggered by B cell antibodies in peripheral tissues. It is crucial to acknowledge that the frequency of B cell infiltration varies among different tumor types. For example, B16F10 melanoma exhibits a high B cell infiltration, accounting for more than 50% of total tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, whereas Yumm 1.7 shows a much lower B cell infiltration with only 2–3% of total tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. This variation directly correlates with NR-V04’s therapeutic outcomes, implying that NR-V04 application may achieve more favorable responses in cancers with high B cell infiltrations.

NR-V04’s impact on the TME extends beyond regulating B cells to influence anti-tumor immunity. NR-V04 decreases mMDSCs (CD11B+Ly6C+) in tumors and blood. mMDSCs are known to suppress the immune response, including B cell function46, 47. Furthermore, B cell activation results in immune complex formation that attracts pro-inflammatory cytokines produced by mMDSCs31, 48. Thus, NR-V04’s action on mMDSC can potentially alleviate immune suppression, thereby enhancing B cell-mediated anti-tumor effects. Moreover, NR-V04 significantly increases CD8+ Tem cells in the spleen of B16F10 melanoma-bearing mice, supporting potential systematic protection of tumor cell recurrence when encountered with those CD8+ Tem cells.

The PK-PD decoupled, long-lasting degradation effect of NR-V04 in vivo (Fig. 6B) is expected for a PROTAC molecule but could also suggest that NR-V04 can specifically accumulate in the tumors, a favorable feature for drug development that warrants reasonable lower effective doses and longer treatment intervals. The warhead used in NR-V04 is celastrol which has been associated with several adverse effects such as hepatotoxicity49, 50, hematopoietic system toxicity51, nephrotoxicity52, weight loss, and negative impact on metabolic and cardiovascular functions53–55. However, with the same treatment regimen, NR-V04 exhibits an excellent safety profile in vivo. This safety advantage could be attributed to NR-V04’s superior specificity as a PROTAC that targets NR4A1 rather than a collection of other known celastrol targets, which reduces off-target effects that could lead to toxicity in patients. One caveat related to the NR-V04 is the usage of VHL which is a well-established tumor suppressor gene56 and very commonly mutated in human cancers such as RCCs. We have been actively developing other E3-recruiting NR4A1 PROTACs, but at the current stage, none of those different PROTACs exhibit better tumor suppression and safety profile than NR-V04.

Materials and Methods

Chemistry

DMF and DCM were obtained via a solvent purification system by filtering through two columns packed with activated alumina and 4 Å molecular sieve, respectively. Water was purified with a Milli-Q Simplicity 185 Water Purification System (Merck Millipore). All other chemicals and solvents obtained from commercial suppliers were used without further purification. Flash chromatography was performed using silica gel (230–400 mesh) as the stationary phase. Reaction progress was monitored by thin-layer chromatography (silica-coated glass plates) and visualized by 256 nm and 365 nm UV light, and/or by LC-MS. 1H NMR spectra were recorded in CDCl3 or CD3OD at 600 MHz, and 13C NMR spectra were recorded at 151 MHz using a Bruker (Billerica, MA) DRX Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectrometer. Chemical shifts δ are given in ppm using tetramethylsilane as an internal standard. Multiplicities of NMR signals are designated as singlet (s), doublet (d), doublet of doublets (dd), triplet (t), quartet (q), A triplet of doublets (td), A doublet of triplets (dt), and multiplet (m). All final compounds for biological testing were of ≥95.0% purity as analyzed by LC-MS, performed on an Advion AVANT LC system with the expression CMS using a Thermo Accucore™ Vanquish™ C18+ UHPLC Column (1.5 μm, 50 × 2.1 mm) at 40 °C. Gradient elution was used for UHPLC with a mobile phase of acetonitrile and water containing 0.1% formic acid. High resolution mass spectra (HRMS) were recorded on an Agilent 6230 Time-of-Flight (TOF) mass spectrometer.

Intermediate 1a to 3a were synthesized according to previously reported procedure57, briefly, to a solution of VHL-amine HCl salt (1.0 equiv), and corresponding acid-terminated linkers (1.0 equiv) in 5 mL DCM was added HATU (1.1 equiv) and DIPEA (5.0 equiv), the reaction was stirred at room temperature overnight. After extraction with EA and brine, the residue was concentrated and purified by silica gel column chromatography to yield 1a to 3a.

tert-butyl (2-(2-(2-(((S)-1-((2S,4R)-4-hydroxy-2-(((S)-1-(4-(4-methylthiazol-5-yl)phenyl)ethyl)carbamoyl)pyrrolidin-1-yl)-3,3-dimethyl-1-oxobutan-2-yl)amino)-2-oxoethoxy)ethoxy)ethyl)carbamate (1a) was obtained as colorless oil with the 93% yield: 1H NMR (600 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 8.67 (s, 1H), 7.57 – 7.35 (m, 5H), 7.33 – 7.27 (m, 1H), 5.20 – 5.03 (m, 1H), 4.79 – 4.50 (m, 3H), 4.17 – 3.80 (m, 3H), 3.69 – 3.49 (m, 7H), 3.45 – 3.28 (m, 2H), 2.57 – 2.51 (m, 4H), 2.22 – 1.99 (m, 1H), 1.59 – 1.48 (m, 12H), 1.05 (s, 9H). ESI [M+H]+ = 690.4

tert-butyl ((S)-13-((2S,4R)-4-hydroxy-2-(((S)-1-(4-(4-methylthiazol-5-yl)phenyl)ethyl)carbamoyl)pyrrolidine-1-carbonyl)-14,14-dimethyl-11-oxo-3,6,9-trioxa-12-azapentadecyl)carbamate (2a) was obtained as colorless oil with the 91% yield: 1H NMR (600 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 8.69 (s, 1H), 7.54 – 7.46 (m, 1H), 7.43 – 7.33 (m, 5H), 5.20 (s, 1H), 5.11 – 5.01 (m, 1H), 4.71 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 4.63 – 4.53 (m, 1H), 4.55 – 4.46 (m, 1H), 4.08 – 3.93 (m, 3H), 3.73 – 3.61 (m, 9H), 3.54 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 2H), 3.36 – 3.26 (m, 2H), 2.52 (s, 3H), 2.42 – 2.34 (m, 1H), 2.15 – 2.07 (m, 1H), 1.48 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H), 1.43 (s, 9H), 1.06 (s, 9H). ESI [M+H]+ = 733.3

tert-butyl ((S)-16-((2S,4R)-4-hydroxy-2-(((S)-1-(4-(4-methylthiazol-5-yl)phenyl)ethyl)carbamoyl)pyrrolidine-1-carbonyl)-17,17-dimethyl-14-oxo-3,6,9,12-tetraoxa-15-azaoctadecyl)carbamate (3a) was obtained as colorless oil with the 91% yield: 1H NMR (600 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 8.68 (s, 1H), 7.46 – 7.41 (m, 1H), 7.41 – 7.35 (m, 4H), 7.26 – 7.20 (m, 1H), 5.27 – 5.16 (m, 1H), 5.10 – 5.02 (m, 1H), 4.70 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 4.59 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 4.51 (s, 1H), 4.06 (s, 2H), 3.95 (d, J = 11.2 Hz, 1H), 3.80 (s, 1H), 3.71 – 3.59 (m, 12H), 3.56 (t, J = 5.2 Hz, 2H), 3.36 – 3.26 (m, 2H), 2.83 – 2.75 (m, 1H), 2.52 (s, 3H), 2.40 – 2.31 (m, 1H), 2.15 – 2.07 (m, 1H), 1.50 – 1.39 (m, 12H), 1.05 (s, 9H). ESI [M+H]+ = 778.4

General procedure for the synthesis of PROTACs: 1a, 2a, or -3a (1.0 equiv) was dissolved in 5 mL DCM/TFA (2:1) and stirred at room temperature for 6h. The resulting mixture was concentrated under vacuum and re-dissolved in DMF, celastrol was added followed by DIPEA (5.0 equiv) and HATU (1.1 equiv). The reaction mixture was then stirred at room temperature overnight. Water (20 mL) and EtOAc (40 mL) were added. The organic phase was washed with brine (10 mL), dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated. The residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography to yield NR-V02, NR-V03, and NR-V04, respectively.

NR-V02 was obtained as red solid (14 mg, 50% yield). 1H NMR (600 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 8.67 (s, 1H), 7.40 – 7.33 (m, 6H), 7.08 (s, 1H), 7.03 (dd, J = 7.1, 1.4 Hz, 1H), 6.53 (s, 1H), 6.44 – 6.40 (m, 1H), 6.34 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 5.11 – 5.07 (m, 1H), 4.72 (t, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 4.56 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 4.52 (s, 1H), 4.12 – 3.96 (m, 3H), 3.76 – 3.13 (m, 12H), 2.52 (s, 3H), 2.47 – 2.39 (m, 2H), 2.20 (s, 3H), 2.17 – 1.76 (m, 7H), 1.69 – 1.41 (m, 11H), 1.24 (s, 3H), 1.16 – 0.97 (m, 16H), 0.61 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 178.52, 178.35, 171.51, 171.10, 170.68, 169.89, 165.08, 150.32, 148.47, 146.11, 143.22, 134.68, 131.61, 130.84, 129.55, 127.28, 126.42, 119.48, 118.11, 117.71, 70.84, 70.14, 70.07, 58.69, 57.46, 56.77, 48.88, 47.40, 46.33, 45.11, 44.36, 43.14, 40.38, 39.39, 39.35, 38.19, 36.35, 35.94, 35.27, 34.87, 33.83, 33.50, 31.62, 31.05, 30.76, 29.96, 29.71, 29.38, 28.64, 26.53, 26.45, 26.39, 22.23, 21.68, 18.40, 16.11, 10.30, 8.72. MS m/z: [M+H]+ calculated for C58H80N5O9S1+: 1022.5671, found 1022.5680.

NR-V03 was obtained as red solid (12 mg, 51% yield). 1H NMR (600 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 8.67 (s, 1H), 7.48 – 7.35 (m, 5H), 7.24 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 7.11 – 7.05 (m, 1H), 7.02 (d, J = 7.0, 1.4 Hz, 1H), 6.53 – 6.50 (m, 1H), 6.37 – 6.30 (m, 2H), 5.14 – 5.05 (m, 1H), 4.72 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 4.57 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 4.52 (s, 1H), 4.09 – 4.00 (m, 3H), 3.87 – 2.98 (m, 16H), 2.53 (s, 3H), 2.50 – 2.39 (m, 2H), 2.20 (s, 3H), 2.15 – 1.81 (m, 7H), 1.69 – 1.36 (m, 11H), 1.25 (s, 3H), 1.12 (d, J = 16.9 Hz, 6H), 1.05 (s, 9H), 1.02 – 0.96 (m, 1H), 0.62 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 178.46, 178.31, 171.44, 170.90, 170.53, 169.90, 165.02, 150.29, 148.48, 146.09, 143.31, 134.51, 131.63, 130.82, 129.54, 127.33, 126.45, 119.45, 118.10, 117.55, 70.67, 70.34, 70.31, 70.12, 69.87, 67.99, 58.60, 57.33, 56.72, 48.84, 47.40, 45.11, 44.37, 43.09, 40.29, 39.34, 39.29, 38.25, 36.35, 35.89, 35.20, 34.92, 33.79, 33.54, 31.62, 31.09, 30.78, 29.99, 29.71, 29.36, 28.68, 26.51, 26.40, 25.62, 22.23, 21.70, 18.38, 16.12, 10.29, 8.73. MS (ESI); m/z: [M+H]+ calculated for C60H84N5O1S1+: 1066.5933, found 1066.5933.

NR-V04 was obtained as red solid (24 mg, 55% yield). 1H NMR (600 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 8.67 (s, 1H), 7.43 – 7.35 (m, 5H), 7.17 (s, 1H), 7.04 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 6.53 (s, 1H), 6.45 (s, 1H), 6.34 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 5.12 – 5.05 (m, 1H), 4.68 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 4.57 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 4.51 (s, 1H), 4.09 – 3.92 (m, 3H), 3.73 – 3.15 (m, 17H), 2.53 (s, 3H), 2.48 – 2.38 (m, 2H), 2.21 (s, 3H), 2.16 – 1.80 (m, 12H), 1.69 – 1.42 (m, 13H), 1.25 (s, 3H), 1.12 (d, J = 14.7 Hz, 6H), 1.06 – 0.92 (m, 10H). 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 179.35, 178.35, 171.61, 171.14, 170.37, 170.25, 165.37, 150.30, 148.41, 146.17, 143.34, 135.18, 131.68, 130.73, 129.52, 127.21, 126.53, 119.36, 118.24, 118.06, 70.89, 70.04, 69.89, 69.66, 69.51, 59.04, 57.30, 56.84, 48.89, 45.20, 44.29, 43.20, 40.44, 39.31, 39.12, 38.19, 36.31, 36.23, 35.51, 34.65, 33.83, 33.55, 31.57, 30.79, 29.75, 29.27, 28.65, 26.36, 22.09, 21.61, 18.30, 16.11, 10.30. MS (ESI); m/z: [M+H]+ calculated for C62H88N5O11S1+: 1110.6196, found 1110.6199.

Single-cell RNA analysis

We utilized multiple datasets from GEO (GSE12057552, GSE14819053, GSE15880354, GSE12163850) and the human TCGA melanoma data cohort for analysis. Data visualization and analysis were conducted using Single Cell Portal, Seurat R package (V2.3.4), and Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA). The code used in our analysis is available on GitHub (https://github.com/Levy0803/NR4A1/projects?query=is%3Aopen).

Cell lines and cell culture

Human melanoma cell lines: A375 and CHL-1 (gift from Dr. Zhou Daohong’s lab) were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagles’ Medium (DMEM, D5796, Sigma), WM164 and M229 (gift from Dr. Smalley Keiran’s lab) were cultured in RPMI-1640 (R8758, Sigma), B16F10 (CRL-6475, ATCC). Mouse melanoma cell lines: SW1 and SM1 (gift from Dr. Smalley Keiran’s lab) were cultured in RPMI. Human epithelial kidney cell lines: HEK293T (293T, CRL-3216, ATCC) and Vhl-KO-293T(gift from Dr. Zhou Daohong’s lab) were cultured in DMEM. Mouse colon cancer cell lines: MC38 (ENH204-FP, Kerafast Inc.) was cultured in DMEM supplemented with 1mM glutamine, 0.1 M non-essential amino acids (11140050, Thermo Fisher), 1 mM sodium pyruvate (11360070, Thermo Fisher), 10 mM HEPES (15630080, Thermo Fisher). All cell culturing medium were supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS, F2442, Sigma) and 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (P4333, Sigma).

Immunoblotting

Samples were lysed using RIPA lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 1% NP-40, 0.5% SDS) supplemented with 1 mM dithiothreitol and protease inhibitors. The lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed using standard western blotting procedures58. Antibodies: human NR4A1 (ab153914, Abcam, 1:1000), mouse NR4A1 (14-5965-82, Invitrogen, 1:1000), NR4A2 (AV38753, Sigma, 1:1000), NR4A3 (TA804893, Thermo Fisher, 1: 1000), VHL (68547,Cell Signaling, 1:1000), β-actin (13E5, Cell Signaling, 1:5,000), β-tubulin (9F3, Cell Signaling, 1: 5000), GAPDH (D16H11, Cell Signaling, 1: 5000) were employed for protein detection.

Cell transfection

HEK293T cells were transfected with 3 μg Flag-NR4A1 (HG17699-CF, SinoBiological, sequencing primer is T7(TAATACGACTCACTATAGGG) BGH(TAGAAGGCACAGTCGAGG), Flag-tag primer is GATTACAAGGATGACGACGATAAG) for 36 hours in Opti-MEM (31985062, Thermo Fisher) medium with 10 μL GeneTran III reagent (GT2211, Biomiga) in 6 cm2 cell culture dishes.

Co-immunoprecipitation

HEK293T cells were transfected with Flag-NR4A1 for 36 hours. Afterward, the cells were treated with either DMSO or 500 μM NR4A1 for 16 hours, and 500 nM MG132 was included to prevent protein degradation. Proteins were extracted using RIPA lysis buffer without SDS (150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 1% NP-40) supplemented with 1% protease inhibitor cocktail (C0001, TargetMol). Immunoprecipitation was performed using Anti-FLAG M2 Magnetic Beads (M8823, Sigma-Aldrich) as per the manufacturer’s protocol. The immunoprecipitated samples were eluted with 2× SDS sample buffer and boiled for 5 minutes at 95°C. The samples were then subjected to denaturation, SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE), and immunoblotting analysis.

Proximity ligation assay (PLA)

5 × 104 CHL-1 and A375 cells were cultured in Nunc™ Lab-Tek™ Chamber Slide (177402, Thermos Fisher). The cells were treated with DMSO, 500 nM celastrol, and 500 nM NR-V04 for 16 hours with MG132 inhibitor. The proximity ligation assay (PLA) was conducted with Duolink® In Situ Red Starter Kit Mouse/Rabbit (DUO92101, Sigma) following the standard protocol. Additionally, a non-stain cell group was included as a negative control to account for background signal during PLA assay. The signal was detected using a Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscope. Primary antibody: NR4A1 (HPA059742, Sigma, 2 μg/mL, isotype-rabbit), VHL (MA5-13940, Thermo Fisher, 2 μg/mL, isotype-mouse).

Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from cells using RNeasy Kits (74004, QIAGEN) following the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA synthesis was performed using SuperScript™ III Reverse Transcriptase (18080044, Thermo Fisher) with 100 ng/μL RNA as the template. Amplification of cDNA was carried out using 2X PowerUP SYBR Green Master Mix (Thermo Fisher, A25778). Each reaction was conducted in triplicates, and results were normalized to the expression of a housekeeping gene. Primer (Eurofins) : human β-actin (Forward Sequence: CACCATTGGCAATGAGCGGTTC; Reverse Sequence: AGGTCTTTGCGGATGTCCACGT), human NR4A1 (Forward Sequence: GGACAACGCTTCATGCCAGCAT; Reverse Sequence: CCTTGTTAGCCAGGCAGATGTAC).

Pharmacokinetic study of NR-V04

The pharmacokinetic study of NR-V04 subjected to PK studies was done by Bioduro Inc. on healthy male C57BL/6 mice weighing between 20 g and 25 g with three animals in each group. Test compound (i.v.) was dissolved in 5% DMSO/3% tween 80 in PBS with 0.5 mEq 1N HCl and was administered (n = 3 per group) at a dose level of 2 mg/kg (concentration: 0.4 mg/mL). Test compounds (i.p.) were dissolved in 5% DMSO/3% tween 80 in PBS with 2 mEq 1N HCl (concentration 4 mg/kg) and were administrated at a dose level of 20 mg/kg. Plasma samples (i.v.) were collected from the orbital plexus at 0.083, 0.25, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 4.0, 8.0 and 24 h, and plasma samples (i.p.) were collected from the orbital plexus at 0.25, 0.50, 1.0, 2.0, 4.0, 8.0, and 24 h postdose. The drug concentrations in the samples were quantified by liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated from the mean plasma concentration by non-compartmental analysis.

B cell proliferation assay

B cells were isolated from the spleen by using EasySep™ Mouse B Cell Isolation Kit (19854, STEMCELL) and cultured in RPMI supplemented with 0.1 M non-essential amino acids (11140050, Thermo Fisher), 1 mM sodium pyruvate (11360070, Thermo Fisher), 1mM Glutamax, 10 mM HEPES (15630080, Thermo Fisher), 0.1% 2-mercaptoethanol (21985023, Thermo Fisher), 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS, F2442, Sigma) and 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (P4333, Sigma). B cells were stained with 5 nM CellTrace™ Violet Cell (C34557, Thermo Fisher) for 8 minutes in 37 °C water bath. B cells were plated at a concentration of 5 × 105 cells per 200μL in round-bottom 96-well plates treated with 0.1% B16F10 melanoma cell lysis or 10 μg/mL goat anti-mouse IgM F(ab’)2 (115-006-020, Jackson ImmunoResearch). B cells were treated with NR-V04 or DMSO for 24 hours and collected for flow cytometry analysis.

Animal Experiment

All animal studies were approved by the University of Florida Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) under protocol 202110399. All animals were housed in a pathogen-free Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care accredited facility at the University of Florida and performed in accordance with IACUC guidelines. The room temperature is 21.1–23.3 °C with an acceptable daily fluctuation of 2 °C. Typically the room is 22.2 °C all the time. The humidity set point is 50% but can vary ±15% daily depending on the weather. The photoperiod is 12:12 and the light intensity range is 15.6–25.8 FC.

7 to 9-week-old C57BL/6J, B6.129S2-Ighmtm1Cgn/J (002288), B6.129S2-Nr4a1tm1Jmi/J (NR4A1−/−, 006187), NOD-SCID interleukin-2 receptor gamma null (NSG) mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). For all studies involving NR-V04 and celastrol, the compounds were formulated in 50% phosal PG, 45% miglyol 810N, and 5% polysorbate 80 and administered via IP injection.

For syngeneic tumor models, 5 × 105 cells MC38, Yumm 1.7 and Yummer 1.7, 1 × 105 cells of B16F10, were resuspended in phosphate buffered saline (PBS), and implanted into 7 to 9-week-old mice subcutaneously. For tumor inhibition experiment, mice were treated with 1.8 mg/kg NR-V04 or 0.75 mg/kg celastrol by IP injection twice weekly. For immune profile experiment, once tumors reached 0.5 cm in diameter, mice were treated with 1.8 mg/kg NR-V04 by IP injection twice weekly. For toxicity experiment, male and female non-tumor bearing mice were treated with 2 mg/kg NR-V04 for two doses for first week and 5 mg/kg for another two doses in second week. Blood samples were taken from the submandibular (facial) vein before each treatment and 42 days later for hematological analysis and body weight were measured twice per week up to day 42. Mice were euthanized in accordance with IACUC protocol once the largest tumors reached 2 cm in diameter and tissues were collected for further analysis.

Flow cytometry

Mouse tumors were excised and ~200 mg of tumor tissue was enzymatically and mechanically digested using the mouse Tumor Dissociation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec) to obtain a single-cell suspension. Human tumor samples and sections were enzymatically and mechanically digested using the human Tumor Dissociation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec) to obtain single-cell suspension. Red blood cells were lysed using ACK lysis buffer and mononuclear cells were isolated by density gradient using SepMate Tubes (StemCell Technologies) and Lymphoprep density gradient media (StemCell Technologies). Mouse cells were then washed and incubated with combinations of the following antibodies: anti-mouse CD62L-BV785 (clone MEL-14), anti-mouse MHCII I-A/I-E-BB515 (Clone 2G9, BD Biosciences, 1:400), anti-mouse CD11B-PEdazzle 594 (clone M1/70, 1:200), anti-mouse CD45-AF532 (clone 30F.11), anti-mouse CD3-APC/Cy7(clone 17A2), anti-mouse CD8-BV510 (clone 53-6.7), anti-mouse CD4-BV605 (clone GK1.5), anti-mouse NK1.1-AF700 (clone PK136), anti-mouse/human CD45R/B220-BV 570 (clone RA3-6B2), anti-mouse CD138-BV711 (clone 281-2), anti-mouse IgD-BV711 (clone 281-2), anti-mouse IgD-PE-Cy7 (clone 11-26c.2a), anti-mouse Ly6G-FITC (clone IA8), anti-mouse Ly6C-BV711 (clone HK1.4), anti-mouse CD38-PerCP/Cy 5.5 (clone 90) anti-mouse IgM-AF488 (clone RMM-1), anti-mouse CD25-PE-Cy5 (clone PC61) plus zombie red (cell viability, Thermo Fisher) and mouse FcR blocker (anti-mouse CD16/CD32, clone 2.4G2, BD Biosciences). After surface staining, cells were fixed and permeabilized using the FOXP3/Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Set (eBioscience). Cells were stained with a combination of the following antibodies: anti-mouse FOXP3-efluor 450 (clone FJK-16S, 1:50, eBioscience), anti-mouse Granzyme B-BV421 (clone GB11), anti-mouse NR4A1-PE (clone 12.14, eBioscience). Human cells were stained with a combination of the following antibodies: anti-human CD45-BV510 (clone H130), anti-human CD3-AF700 (clone HIT5a), anti-human CD4-BV421 (clone OKT4), anti-human CD8-BV711 (clone RPA-T8), anti-human CD127-BV605 (clone A019DS), anti-human CD25-PE-Cy7 (clone MA251) plus FVD-eFluor-780 (eBioscience) and human FcR blocking Reagent (StemCell Technologies). Cells were washed then fixed and permeabilized using the eBioscience FOXP3/Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Set. Cells were further stained with a combination of the following antibodies: anti-human FOXP3-FITC (clone 206D), anti-human NR4A1-PE (clone D63C5, Cell Signaling). Flow cytometry was performed on a 3 laser Cytek Aurora Cytometer (Cytek Biosciences, Fremont, CA) and analyzed using FlowJo software (BD Biosciences). All antibodies are from Biolegend, unless otherwise specified. Most antibodies were used at 1:100 dilution for flow cytometry, unless otherwise specified.

Hematology analysis

Mouse blood was prepared in micro-centrifuge tubes containing PBS with 10 mM EDTA. Blood indices were analyzed using an automated hematology analyzer (Element HT5, Heska).

H&E staining

H&E staining for mouse tissues were fixed in 10% formalin (SF98-4, Thermo Fisher) processed in UF pathology core. H&E staining was conducted using standard procedures. The sections were hydrated through xylene and a series of ethanol, followed by staining with Hematoxylin and Eosin on slides.

Statistics

Graphs and statistical analyses were performed using Prism software (GraphPad Software) unless otherwise specified. Tumor growth curves were compared using a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). For comparisons involving three or more groups, a one-way ANOVA was conducted, followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test for specific group comparisons. Unpaired T tests were used to compare means between two groups.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

The work is mainly supported by DOD/CDMRP grant BC200100 (Partnering PIs: W.Z. and G.Z.) and an iAward from Sanofi (PI: W.Z.). The work is partially supported by NIH grants CA200673 (W.Z.), CA203834 (W.Z.), CA260239 (W.Z.), and DOD/CDMRP grant BC200100 (W.Z.). W.Z. was also supported by an endowment fund from the Dr. and Mrs. James Robert Spenser Family.

Conflict of Interests:

This project was partially supported by an iAward from Sanofi. W.Z., G.Z., D.Z., Y.X., and L.W. hold a patent related to the compound used in this study. X.L., D.S., K.R.G. are Sanofi Employees and holding Sanofi stocks.

Reference

- 1.Liu X, Wang Y, Lu H, Li J, Yan X, Xiao M, Hao J, Alekseev A, Khong H, Chen T. Genome-wide analysis identifies NR4A1 as a key mediator of T cell dysfunction. Nature. 2019;567(7749):525–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hiwa R, Nielsen HV, Mueller JL, Mandla R, Zikherman J. NR4A family members regulate T cell tolerance to preserve immune homeostasis and suppress autoimmunity. JCI insight. 2021;6(17). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tan C, Hiwa R, Mueller JL, Vykunta V, Hibiya K, Noviski M, Huizar J, Brooks JF, Garcia J, Heyn C. NR4A nuclear receptors restrain B cell responses to antigen when second signals are absent or limiting. Nature immunology. 2020;21(10):1267–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fassett MS, Jiang W, D’Alise AM, Mathis D, Benoist C. Nuclear receptor Nr4a1 modulates both regulatory T-cell (Treg) differentiation and clonal deletion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2012;109(10):3891–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zeng H, Qin L, Zhao D, Tan X, Manseau EJ, Van Hoang M, Senger DR, Brown LF, Nagy JA, Dvorak HF. Orphan nuclear receptor TR3/Nur77 regulates VEGF-A-induced angiogenesis through its transcriptional activity. J Exp Med. 2006;203(3):719–29. Epub 2006/03/08. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ha CH, Wang W, Jhun BS, Wong C, Hausser A, Pfizenmaier K, McKinsey TA, Olson EN, Jin ZG. Protein kinase D-dependent phosphorylation and nuclear export of histone deacetylase 5 mediates vascular endothelial growth factor-induced gene expression and angiogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(21):14590–9. Epub 2008/03/12. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800264200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ismail H, Mofarrahi M, Echavarria R, Harel S, Verdin E, Lim HW, Jin ZG, Sun J, Zeng H, Hussain SN. Angiopoietin-1 and vascular endothelial growth factor regulation of leukocyte adhesion to endothelial cells: role of nuclear receptor-77. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32(7):1707–16. Epub 2012/05/26. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.251546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen C, Li Y, Hou S, Bourbon PM, Qin L, Zhao K, Ye T, Zhao D, Zeng H. Orphan nuclear receptor TR3/Nur77 biologics inhibit tumor growth by targeting angiogenesis and tumor cells. Microvasc Res. 2020;128:103934. Epub 2019/10/28. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2019.103934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ye T, Peng J, Liu X, Hou S, Niu G, Li Y, Zeng H, Zhao D. Orphan nuclear receptor TR3/Nur77 differentially regulates the expression of integrins in angiogenesis. Microvasc Res. 2019;122:22–33. Epub 2018/11/06. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2018.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhao D, Qin L, Bourbon PM, James L, Dvorak HF, Zeng H. Orphan nuclear transcription factor TR3/Nur77 regulates microvessel permeability by targeting endothelial nitric oxide synthase and destabilizing endothelial junctions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108(29):12066–71. Epub 2011/07/07. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018438108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen J, López-Moyado IF, Seo H, Lio C-WJ, Hempleman LJ, Sekiya T, Yoshimura A, Scott-Browne JP, Rao A. NR4A transcription factors limit CAR T cell function in solid tumours. Nature. 2019;567(7749):530–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hibino S, Chikuma S, Kondo T, Ito M, Nakatsukasa H, Omata-Mise S, Yoshimura A. Inhibition of Nr4a receptors enhances antitumor immunity by breaking Treg-mediated immune tolerance. Cancer Research. 2018;78(11):3027–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu W, He J, Wang F, He Q, Shi Y, Tao X, Sun B. NR4A1 mediates NK - cell dysfunction in hepatocellular carcinoma via the IFN - γ/p - STAT1/IRF1 pathway. Immunology. 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Griss J, Bauer W, Wagner C, Simon M, Chen M, Grabmeier-Pfistershammer K, Maurer-Granofszky M, Roka F, Penz T, Bock C. B cells sustain inflammation and predict response to immune checkpoint blockade in human melanoma. Nature communications. 2019;10(1):4186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Corson TW, Crews CM. Molecular understanding and modern application of traditional medicines: triumphs and trials. Cell. 2007;130(5):769–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang D, Chen Z, Hu C, Yan S, Li Z, Lian B, Xu Y, Ding R, Zeng Z, Zhang XK, Su Y. Celastrol binds to its target protein via specific noncovalent interactions and reversible covalent bonds. Chem Commun (Camb). 2018;54(91):12871–4. Epub 2018/10/31. doi: 10.1039/c8cc06140h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen Z, Zhang D, Yan S, Hu C, Huang Z, Li Z, Peng S, Li X, Zhu Y, Yu H, Lian B, Kang Q, Li M, Zeng Z, Zhang XK, Su Y. SAR study of celastrol analogs targeting Nur77-mediated inflammatory pathway. Eur J Med Chem. 2019;177:171–87. Epub 2019/05/28. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu M, Luo Q, Alitongbieke G, Chong S, Xu C, Xie L, Chen X, Zhang D, Zhou Y, Wang Z. Celastrolinduced Nur77 interaction with TRAF2 alleviates inflammation by promoting mitochondrial ubiquitination and autophagy. Molecular cell. 2017;66(1):141–53. e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shi J, Li J, Xu Z, Chen L, Luo R, Zhang C, Gao F, Zhang J, Fu C. Celastrol: a review of useful strategies overcoming its limitation in anticancer application. Frontiers in pharmacology. 2020;11:558741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hu M, Luo Q, Alitongbieke G, Chong S, Xu C, Xie L, Chen X, Zhang D, Zhou Y, Wang Z, Ye X, Cai L, Zhang F, Chen H, Jiang F, Fang H, Yang S, Liu J, Diaz-Meco MT, Su Y, Zhou H, Moscat J, Lin X, Zhang XK. Celastrol-Induced Nur77 Interaction with TRAF2 Alleviates Inflammation by Promoting Mitochondrial Ubiquitination and Autophagy. Mol Cell. 2017;66(1):141–53 e6. Epub 2017/04/08. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schapira M, Calabrese MF, Bullock AN, Crews CM. Targeted protein degradation: expanding the toolbox. Nature reviews Drug discovery. 2019;18(12):949–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Békés M, Langley DR, Crews CM. PROTAC targeted protein degraders: the past is prologue. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2022;21(3):181–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim MC, Borcherding N, Ahmed KK, Voigt AP, Vishwakarma A, Kolb R, Kluz PN, Pandey G, De U, Drashansky T, Helm EY, Zhang X, Gibson-Corley KN, Klesney-Tait J, Zhu Y, Lu J, Lu J, Huang X, Xiang H, Cheng J, Wang D, Wang Z, Tang J, Hu J, Wang Z, Liu H, Li M, Zhuang H, Avram D, Zhou D, Bacher R, Zheng SG, Wu X, Zakharia Y, Zhang W. CD177 modulates the function and homeostasis of tumor-infiltrating regulatory T cells. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):5764. Epub 2021/10/03. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-26091-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; BCL-X(L) PROTACs as senolytic and antitumor agents. D.Z. is the co-founder of, and D.Z. and W.Z. have equity in, Dialectic Therapeutics, which develops BCL-X(L) PROTACs for the treatment of cancer. The other authors have no competing interests.

- 24.Zheng C, Zheng L, Yoo JK, Guo H, Zhang Y, Guo X, Kang B, Hu R, Huang JY, Zhang Q, Liu Z, Dong M, Hu X, Ouyang W, Peng J, Zhang Z. Landscape of Infiltrating T Cells in Liver Cancer Revealed by Single-Cell Sequencing. Cell. 2017;169(7):1342–56 e16. Epub 2017/06/18. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sade-Feldman M, Yizhak K, Bjorgaard SL, Ray JP, de Boer CG, Jenkins RW, Lieb DJ, Chen JH, Frederick DT, Barzily-Rokni M, Freeman SS, Reuben A, Hoover PJ, Villani AC, Ivanova E, Portell A, Lizotte PH, Aref AR, Eliane JP, Hammond MR, Vitzthum H, Blackmon SM, Li B, Gopalakrishnan V, Reddy SM, Cooper ZA, Paweletz CP, Barbie DA, Stemmer-Rachamimov A, Flaherty KT, Wargo JA, Boland GM, Sullivan RJ, Getz G, Hacohen N. Defining T Cell States Associated with Response to Checkpoint Immunotherapy in Melanoma. Cell. 2018;175(4):998–1013 e20. Epub 2018/11/06. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.10.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu L, Chen L. Characteristics of Nur77 and its ligands as potential anticancer compounds (Review). Mol Med Rep. 2018;18(6):4793–801. Epub 2018/10/03. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2018.9515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meeth K, Wang JX, Micevic G, Damsky W, Bosenberg MW. The YUMM lines: a series of congenic mouse melanoma cell lines with defined genetic alterations. Pigment cell & melanoma research. 2016;29(5):590–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li H, Kolluri SK, Gu J, Dawson MI, Cao X, Hobbs PD, Lin B, Chen G-q, Lu J-s, Lin F. Cytochrome c release and apoptosis induced by mitochondrial targeting of nuclear orphan receptor TR3. Science. 2000;289(5482):1159–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li X-x, Wang Z-j, Zheng Y, Guan Y-f, Yang P-b, Chen X, Peng C, He J-p, Ai Y-l, Wu S-f. Nuclear receptor Nur77 facilitates melanoma cell survival under metabolic stress by protecting fatty acid oxidation. Molecular cell. 2018;69(3):480–92. e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith AG, Lim W, Pearen M, Muscat GE, Sturm RA. Regulation of NR4A nuclear receptor expression by oncogenic BRAF in melanoma cells. Pigment cell & melanoma research. 2011;24(3):551–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fridman WH, Meylan M, Petitprez F, Sun C-M, Italiano A, Sautès-Fridman C. B cells and tertiary lymphoid structures as determinants of tumour immune contexture and clinical outcome. Nature reviews Clinical oncology. 2022;19(7):441–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sautès-Fridman C, Petitprez F, Calderaro J, Fridman WH. Tertiary lymphoid structures in the era of cancer immunotherapy. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2019;19(6):307–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.De Visser KE, Korets LV, Coussens LM. De novo carcinogenesis promoted by chronic inflammation is B lymphocyte dependent. Cancer cell. 2005;7(5):411–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.DeNardo DG, Andreu P, Coussens LM. Interactions between lymphocytes and myeloid cells regulate pro-versus anti-tumor immunity. Cancer and Metastasis Reviews. 2010;29:309–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.DiLillo DJ, Yanaba K, Tedder TF. B cells are required for optimal CD4+ and CD8+ T cell tumor immunity: therapeutic B cell depletion enhances B16 melanoma growth in mice. The Journal of Immunology. 2010;184(7):4006–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sharonov GV, Serebrovskaya EO, Yuzhakova DV, Britanova OV, Chudakov DM. B cells, plasma cells and antibody repertoires in the tumour microenvironment. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2020;20(5):294–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reuschenbach M, von Knebel Doeberitz M, Wentzensen N. A systematic review of humoral immune responses against tumor antigens. Cancer immunology, immunotherapy. 2009;58:1535–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garaud S, Zayakin P, Buisseret L, Rulle U, Silina K, De Wind A, Van den Eyden G, Larsimont D, Willard-Gallo K, Linē A. Antigen specificity and clinical significance of IgG and IgA autoantibodies produced in situ by tumor-infiltrating B cells in breast cancer. Frontiers in immunology. 2018;9:2660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Montfort A, Pearce O, Maniati E, Vincent BG, Bixby L, Böhm S, Dowe T, Wilkes EH, Chakravarty P, Thompson R. A strong B-cell response is part of the immune landscape in human high-grade serous ovarian metastases. Clinical Cancer Research. 2017;23(1):250–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Biswas S, Mandal G, Payne KK, Anadon CM, Gatenbee CD, Chaurio RA, Costich TL, Moran C, Harro CM, Rigolizzo KE. IgA transcytosis and antigen recognition govern ovarian cancer immunity. Nature. 2021;591(7850):464–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bruno TC, Ebner PJ, Moore BL, Squalls OG, Waugh KA, Eruslanov EB, Singhal S, Mitchell JD, Franklin WA, Merrick DT. Antigen-presenting intratumoral B cells affect CD4+ TIL phenotypes in non–small cell lung cancer patients. Cancer immunology research. 2017;5(10):898–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wennhold K, Thelen M, Lehmann J, Schran S, Preugszat E, Garcia-Marquez M, Lechner A, Shimabukuro-Vornhagen A, Ercanoglu MS, Klein F. CD86+ antigen-presenting B cells are increased in cancer, localize in tertiary lymphoid structures, and induce specific T-cell responses. Cancer immunology research. 2021;9(9):1098–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nielsen JS, Sahota RA, Milne K, Kost SE, Nesslinger NJ, Watson PH, Nelson BH. CD20+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes have an atypical CD27− memory phenotype and together with CD8+ T cells promote favorable prognosis in ovarian cancer. Clinical cancer research. 2012;18(12):3281–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.von Bergwelt-Baildon MS, Vonderheide RH, Maecker B, Hirano N, Anderson KS, Butler MO, Xia Z, Zeng WY, Wucherpfennig KW, Nadler LM. Human primary and memory cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses are efficiently induced by means of CD40-activated B cells as antigen-presenting cells: potential for clinical application. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology. 2002;99(9):3319–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nutt SL, Hodgkin PD, Tarlinton DM, Corcoran LM. The generation of antibody-secreting plasma cells. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2015;15(3):160–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li K, Shi H, Zhang B, Ou X, Ma Q, Chen Y, Shu P, Li D, Wang Y. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as immunosuppressive regulators and therapeutic targets in cancer. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy. 2021;6(1):362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang Y, Schafer CC, Hough KP, Tousif S, Duncan SR, Kearney JF, Ponnazhagan S, Hsu H-C, Deshane JS. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells impair B cell responses in lung cancer through IL-7 and STAT5. The Journal of Immunology. 2018;201(1):278–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rosser EC, Oleinika K, Tonon S, Doyle R, Bosma A, Carter NA, Harris KA, Jones SA, Klein N, Mauri C. Regulatory B cells are induced by gut microbiota–driven interleukin-1β and interleukin-6 production. Nature medicine. 2014;20(11):1334–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sun M, Tang Y, Ding T, Liu M, Wang X. Inhibitory effects of celastrol on rat liver cytochrome P450 1A2, 2C11, 2D6, 2E1 and 3A2 activity. Fitoterapia. 2014;92:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jin C, Wu Z, Wang L, Kanai Y, He X. CYP450s-activity relations of celastrol to interact with triptolide reveal the reasons of hepatotoxicity of Tripterygium wilfordii. Molecules. 2019;24(11):2162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lipsky PE, Tao X-L, editors. A potential new treatment for rheumatoid arthritis: thunder god vine. Seminars in arthritis and rheumatism; 1997: Elsevier. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wu M, Chen W, Yu X, Ding D, Zhang W, Hua H, Xu M, Meng X, Zhang X, Zhang Y. Celastrol aggravates LPS-induced inflammation and injuries of liver and kidney in mice. American journal of translational research. 2018;10(7):2078. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Saito K, Davis KC, Morgan DA, Toth BA, Jiang J, Singh U, Berglund ED, Grobe JL, Rahmouni K, Cui H. Celastrol reduces obesity in MC4R deficiency and stimulates sympathetic nerve activity affecting metabolic and cardiovascular functions. Diabetes. 2019;68(6):1210–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu J, Lee J, Hernandez MAS, Mazitschek R, Ozcan U. Treatment of obesity with celastrol. Cell. 2015;161(5):999–1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Feng X, Guan D, Auen T, Choi JW, Salazar Hernández MA, Lee J, Chun H, Faruk F, Kaplun E, Herbert Z. IL1R1 is required for celastrol’s leptin-sensitization and antiobesity effects. Nature medicine. 2019;25(4):575–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gossage L, Eisen T, Maher ER. VHL, the story of a tumour suppressor gene. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2015;15(1):55–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Xiao Y, Wang J, Zhao LY, Chen X, Zheng G, Zhang X, Liao D. Discovery of histone deacetylase 3 (HDAC3)-specific PROTACs. Chem Commun (Camb). 2020;56(68):9866–9. Epub 2020/08/26. doi: 10.1039/d0cc03243c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Khan S, Zhang X, Lv D, Zhang Q, He Y, Zhang P, Liu X, Thummuri D, Yuan Y, Wiegand JS. A selective BCL-XL PROTAC degrader achieves safe and potent antitumor activity. Nature medicine. 2019;25(12):1938–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.