Summary

Pituitary organoids are promising graft sources for transplantation in treatment of hypopituitarism. Building on development of self-organizing culture to generate pituitary-hypothalamic organoids (PHOs) using human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs), we established techniques to generate PHOs using feeder-free hPSCs and to purify pituitary cells. The PHOs were uniformly and reliably generated through preconditioning of undifferentiated hPSCs and modulation of Wnt and TGF-β signaling after differentiation. Cell sorting using EpCAM, a pituitary cell-surface marker, successfully purified pituitary cells, reducing off-target cell numbers. EpCAM-expressing purified pituitary cells reaggregated to form three-dimensional pituitary spheres (3D-pituitaries). These exhibited high adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) secretory capacity and responded to both positive and negative regulators. When transplanted into hypopituitary mice, the 3D-pituitaries engrafted, improved ACTH levels, and responded to in vivo stimuli. This method of generating purified pituitary tissue opens new avenues of research for pituitary regenerative medicine.

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

100% of Ff-hPSC-derived pituitary-hypothalamic organoids contained ACTH+ cells

-

•

Cell sorting for EpCAM expression purified pituitary cells, reducing off-target cells

-

•

3D-pituitary transplantation resulted in long-lasting improvement in ACTH levels

-

•

Various challenges to transplanted mice evoked appropriate ACTH responses

Suga and colleagues develop strategies to generate and to purify ACTH-secreting hPSC-derived pituitary cells for clinical applications. Transplantation of purified 3D-pituitaries into hypopituitary mice demonstrated long-term efficacy and environmental control of ACTH secretion, suggesting low risk of iatrogenic Cushing’s syndrome and acute adrenal insufficiency. Our strategies open new avenues toward high-quality pituitary cell production suitable for pituitary regenerative medicine.

Introduction

The pituitary gland regulates various hormones, controlling various processes of growth, homeostasis, metabolism, stress response, and reproduction. Pituitary gland impairment can result in severe systemic manifestations such as hypotension, electrolyte imbalance, impaired consciousness, growth disorders, and infertility (Schneider et al., 2007). Hypopituitarism treatment involves lifelong hormone replacement, as no cure now exists. However, this poses challenges in stress-response regulation. Insufficient replacement of glucocorticoids may yield fatal adrenal crisis, whereas excessive replacement may cause iatrogenic Cushing’s syndrome. Furthermore, physiological adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) requirements fluctuate with circadian rhythms and external stress (Hahner et al., 2015; Stewart et al., 2016). To determine ACTH concentrations for varying demands and to supply oral medication in appropriate doses is difficult. For this reason, if human pituitary tissue that responds to the surrounding environment can be generated using pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) and refined suitably for clinical use, regenerative medicine treatment for hypopituitarism will improve.

Several studies have differentiated PSC-derived pituitary cells in vitro using three-dimensional (3D) floating culture and 2D adhesion culture (Dincer et al., 2013; Kasai et al., 2020; Ozone et al., 2016; Suga et al., 2011; Zimmer et al., 2016). We have generated functional pituitary-hypothalamic organoids (PHOs) from mouse embryonic stem cells (ESCs), human ESCs (hESCs), and human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) using 3D culture (Kasai et al., 2020; Ozone et al., 2016; Suga et al., 2011), aiming to use 3D organoids clinically. This study sought improved efficiency of 3D differentiation, with enhanced purity, of pituitary tissue for transplantation (TX) (purified pituitary spheres), combining three routes: (1) bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP4)/smoothened agonist (SAG; sonic hedgehog [Shh] signal agonist) treatment can generate human PSC (hPSC)-derived PHOs (Kasai et al., 2020; Ozone et al., 2016). The hypothalamus is derived from neural ectoderm; the pituitary is derived from non-neural ectoderm (Davis et al., 2013; Rizzoti and Lovell-Badge, 2005; Takuma et al., 1998). TGF-β/Activin signaling is involved/Activin/BMP, FGF, Shh, Wnt, and other growth factor signaling pathways subserve neural and non-neural ectoderm differentiation (Saint-Jeannet and Moody, 2014; Zhu et al., 2007). Combining activators and inhibitors of these pathways yielded differentiation closely tracking in vivo development. (2) hESCs and iPSCs were hitherto maintained on mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) feeder layers (Kasai et al., 2020; Ozone et al., 2016). Animal-derived products of feeder cell co-culture impede generation of clinical-grade human pituitary tissues. This prompted development of hPSC feeder-free (Ff) differentiation. (3) Clinically important in pituitary hPSC work is controlling the number of off-target cells, viz., undifferentiated or differentiated non-pituitary cells. Cell sorting using cell-surface antigens removes off-target cells and purifies target cell populations (Doi et al., 2014).

This study sought in sum uniformly, reliably, and efficiently to differentiate human pituitary tissue from hPSCs maintained in Ff culture and to purify pituitary cells via cell-surface antigens, yielding pituitary elements suitable for clinical use.

Results

Ff method for differentiation of hPSCs into PHOs

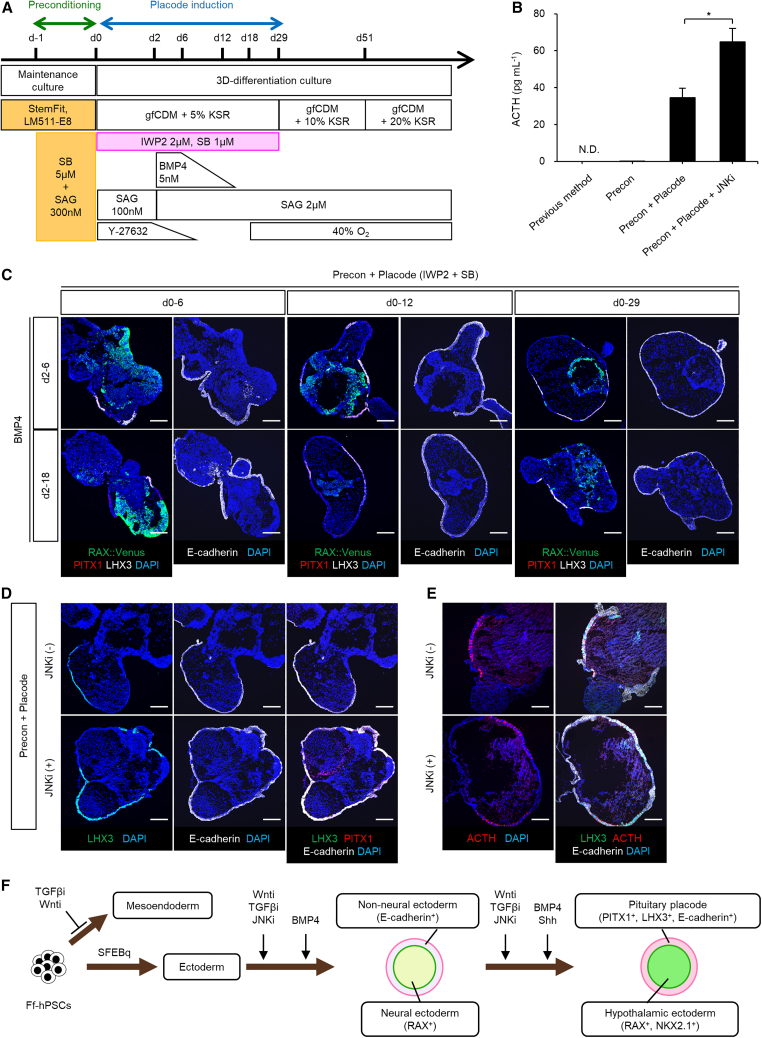

Ff-hPSCs maintained and cultured on LM511-E8 matrix in StemFit medium (Nakagawa et al., 2014) were examined for pituitary and hypothalamus differentiation in serum-free floating culture of embryoid body-like aggregates using the quick reaggregation (SFEBq) method (Eiraku et al., 2008). ACTH concentrations in day 103 organoid culture supernatant tracked functional differentiation. Ff-RAX::Venus reporter hESCs differentiated under conditions like those using MEF (previous method) (Ozone et al., 2016), but Ff-hESC-derived aggregates grew poorly, tending to collapse. Preconditioning of undifferentiated Ff-hPSCs with SB431542 (SB; TGF-β/Activin signaling is involved/Activin signal inhibitor) and SAG for 18–28 h promoted self-formation, with aggregate growth (Figure 1A, preconditioning), as with 3D neural tissue in retinal differentiation culture (Kuwahara et al., 2019). However, supernatant ACTH concentrations were low (Figure 1B, precon). On day 32, immunostaining of PHOs generated with preconditioning revealed two tissues. Neuroepithelium expressed RAX and oral ectoderm expressed the non-neuroepithelium markers PITX1 (early pituitary marker) and E-cadherin (Figure S1A). However, the pituitary precursor cell marker LHX3 was not similarly demonstrable (data not shown). These observations suggest that Ff-hPSCs thus cultured can differentiate to form neural/non-neural two-layered organoids but lack efficient pituitary placode induction.

Figure 1.

Treatment with IWP2/SB/JNKi promotes pituitary differentiation from hPSCs

(A) Culture protocol for pituitary placode induction.

(B) ACTH secretion in culture medium of day 103 aggregates. N.D.; not detected. Previous method and Precon (n = 2 experiments) derived from Ff-RAX::Venus cells, Precon + Placode (n = 4 experiments) and Precon + Placode + JNKi (n = 6 experiments) derived from Ff-201B7 cells. Data represent mean ± SEM. ∗p < 0.05 using Student’s t test.

(C) Immunohistochemical analysis of Ff-RAX::Venus-derived aggregates on day 29 under six differentiating conditions, viz., treatment with IWP2/SB (days 0–6, left; days 0–12, center; days 0–29, right) and BMP4 (days 2–6, upper; days 2–18, lower). Markers, RAX::Venus, PITX1, and LHX3 (left) and E-cadherin (right).

(D) Immunostained Ff-201B7-derived aggregates on day 29 under differentiation conditions with (lower) or without JNKi (upper). Markers, LHX3, PITX1, and E-cadherin.

(E) Immunostained Ff-201B7-derived aggregates on day 103 under differentiation conditions with (lower) or without JNKi (upper). Markers, LHX3, ACTH, and E-cadherin.

(F) Schema, generation of PHOs in 3D culture of Ff-hPSCs.

Scale bars, 200 μm (C, D, and E).

We optimized signaling pathways to regulate positional information in non-neural ectoderm, thereby generating self-forming pituitary placodes. Figure 1A schematizes how TGF-β/Nodal/Activin/BMP and Wnt signaling pathways were studied in differentiation of hPSCs into both neural and non-neural ectoderm and subsequently into pituitary placodes. Preconditioned Ff-RAX::Venus reporter hESCs were differentiated with BMP4 and SAG, as before, in combination with a Wnt signal inhibitor (IWP2; Wnti) and SB (IWP2 + SB, “placode induction”). On day 29, aggregates had PITX1+ and E-cadherin+ outer-layer non-neuroepithelia and RAX+ inner-layer neuroepithelia (Figure 1C). The PITX1+ and E-cadherin+ non-neuroepithelia contained LHX3+ cells (Figure 1C). PITX1+/LHX3+ non-neuroepithelium formed most efficiently with IWP2 + SB during days 0–29 and BMP4 during days 2–6, suggesting that IWP2 + SB treatment with BMP4 and SAG promoted pituitary placode induction. High- and low-concentration treatments (respectively, IWP2 2 μM, BMP4 5 nM, SAG 2 μM, IWP2 0.5 μM, BMP4 0.5 nM, and SAG 700 nM) in Ff-KhES1 cells showed higher supernatant ACTH values (day 61) with low-concentration treatments (Figure S1B).

Inhibition of c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), a mitogen-activated protein kinase, promotes ectodermal-epithelium differentiation of hPSCs (Kobayashi et al., 2020). Ff-human iPSC line (201B7) aggregates treated with the JNK inhibitor JNK-IN-8 (JNKi, 1 μM) during days 0–30 had more outer-layer E-cadherin+ non-neuroepithelial cells and increased LHX3 expression on day 29 (JNKi(+) 9.5% ± 1.4% and JNKi(−) 2.5% ± 0.3% of total cells, mean ± SEM, n = 12) (Figure 1D); on day 103, numbers of ACTH-expressing cells and ACTH secretion were increased (JNKi(+) 42.2% ± 4.4% and JNKi(−) 28.8% ± 4.0% of total cells, mean ± SEM, n = 8–12) (Figures 1B and 1E). Preconditioning/placode induction/JNKi treatment yielded ACTH secretion twice as high as that using MEF (Kasai et al., 2020; Ozone et al., 2016). To evaluate treatment efficiency, we performed qPCR for pituitary markers PITX1, CDH1 (E-cadherin), and LHX3 on day 29 (Figure S1C). Placode induction treatment was essential and JNKi enhanced induction. Another Ff-human iPSC line (1231A3) was also used to confirm formation of outer-layer pituitary epithelium and the presence of ACTH-expressing cells (Figures S1D–S1F). Organoids secreted more ACTH when SAG addition, with JNKi, ceased on day 30 than when it continued (Figure S1G).

In sum, BMP4/Shh combined with Wnti/TGF-βi efficiently induced formation of neural/non-neural ectoderm and pituitary placode, with differentiation into pituitary and hypothalamic tissues. JNKi enhanced efficiency of pituitary placode differentiation. Timed exposure to Shh induced pituitary placode and hypothalamus formation and promoted pituitary maturation (Figure 1F). This approach improved induction of Ff-PHO differentiation (Figure 2A).

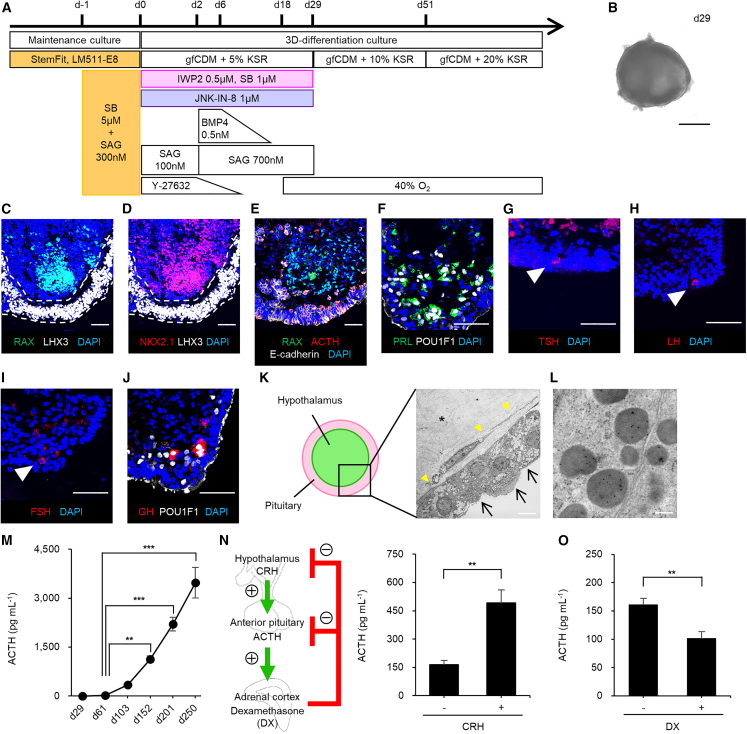

Figure 2.

Differentiation and functional characterization of Ff-KhES1-derived PHOs

(A) Culture protocol, PHO induction.

(B) Bright-field image, day 29 aggregates.

(C and D) Immunostained day 29 aggregates, pituitary and hypothalamic markers. Markers, RAX and LHX3 (C) and NKX2.1 and LHX3 (D).

(E) Immunostained day 103 aggregates; RAX, ACTH, and E-cadherin.

(F) Immunostained day 103 aggregates; PRL and POU1F1.

(G–I) Immunostained day 103 aggregates; TSH (G), LH (H), and FSH (I).

(J) Immunostained day 103 aggregates; GH and POU1F1.

(K and L) Electron micrographs (K) and immunoelectron micrographs for ACTH and GH (L) of Ff-KhES1-derived pituitary-hypothalamic aggregates and corticotrophs, day 201. ACTH-granules (10 nm), GH granules (20 nm, none). Arrows, cilia; asterisk, hypothalamic tissue; yellow arrowheads, basement membrane.

(M) Long-term ACTH secretion, culture medium (n = 4–17 experiments).

(N) CRH efficiently induced ACTH secretion (n = 5 experiments).

(O) Dexamethasone suppressed ACTH secretion (n = 5 experiments).

Scale bars, 500 μm (B), 50 μm (C–J), 8 μm (K), and 200 nm (L). Data presented as mean ± SEM. ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001 using one-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey (M) and paired t test (N and O).

Characteristics of Ff-hESC/iPSC-derived PHOs

Analysis by qPCR of genes encoding pituitary markers PITX1, LHX3, and POMC (ACTH precursor) and hypothalamic markers RAX and TTF1 (Nkx2.1) (Figures S2A and S2B) tracked differentiation of PHOs. PITX1 mRNA levels rose from day 6 to day 60 and then fell gradually. LHX3 mRNA levels rose from day 19 to day 30 and then fell gradually. POMC mRNA levels rose from day 30 onward. These results indicate stepwise progression of pituitary tissue differentiation. RAX mRNA levels plateaued from day 3 to day 6 and then fell. TTF1 mRNA levels rose from day 6 to day 19 and then fell. These results suggest linked early-stage differentiation of ventral hypothalamus and of pituitary precursor tissue. On day 29 (Figure 2B), LHX3+ cells (16.2% ± 2.2% of total cells, mean ± SEM, n = 4) were observed in the outer layer of the organoids and ventral-hypothalamus neuroepithelium (RAX+/NKX2.1+) was observed in the inner layer (RAX 2.2% ± 0.7% and NKX2.1 32.7% ± 5.4% of total cells, mean ± SEM, n = 4) (Figures 2C and 2D). On day 103, two layers (ACTH-expressing pituitary cells and RAX+ hypothalamic cells) were observed (Figure 2E). These data indicate that PHOs form as tissue-type dyads (Kasai et al., 2020; Ozone et al., 2016). Cells producing prolactin (PRL), thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) were observed on day 103 (PRL 3.3% ± 0.5% and TSH, LH, FSH <1% of total cells, mean ± SEM, n = 8) (Figures 2F–2I). Cells producing growth hormone (GH) were observed on day 152 (GH <1% of total cells, n = 8) (Figure 2J). PHOs on days 131–138 secreted ACTH and PRL but only scant GH, TSH, LH, and FSH, indicating that ACTH secretion predominates, but is not specific (Table S1). These findings confirm that Ff-hPSC-derived pituitary precursor cells can generate multiple endocrine lineages in culture (Ozone et al., 2016).

We evaluated the structure of Ff-hESC-derived PHOs using electron microscopy. Many pituitary tissue cells contained hormone secretory granules on day 201 (Figures 2K and S2C–S2E). Immunogold labeling marked most granules for ACTH and none for GH (Figure 2L). The hypothalamic inner layer of the organoid, especially at depth, was necrotic or fibrotic (Figure 2K). Within the organoid wall, endocrine cells with intracellular secretory granules resembled adenohypophyseal cells (Figure S2C). The pituitary cell layer formed a thin cyst wall at many sites, consisting of an endocrine cell pseudostratified columnar epithelium, with a basement membrane-like structure at the deepest and ciliated cells at the most superficial. Dispersed endocrine cells rich in secretory granules were present but lacked prominent bundles of intermediate filaments. The type of endocrine cells was obscure. They seemed strongly polarized in the direction of the basement membrane and outer boundary (basally); for instance, desmosomes were unevenly distributed toward the outer layers (Figure S2D). In addition, some folliculo-stellate cells (FSCs) lay in the organoid walls (Figure S2E). FSCs in the pituitary gland may act as pituitary stem cells (Horvath and Kovacs, 2002). Immunostaining for the FSC marker S100 and pituitary stem cell markers, SOX2, CD133, and coxsackievirus/adenovirus receptor (CXADR) (Chen et al., 2013; Vankelecom, 2016) on day 103 showed almost no S100+ cells in the pituitary zone (<0.1% of total cells), suggesting that few FSCs were induced (Figure S2F). Many SOX2+ and SOX2+/CD133+ cells were observed, with few SOX2+/S100+ cells, as pituitary stem cells (Figure S2F). ACTH-expressing and CXADR+ cells without ACTH expression were localized opposite each other, demonstrating polarity of hormone-producing cells and pituitary stem cells (Figure S2G). To our knowledge, this is the first report of pituitary stem cells in Ff-hPSC-derived PHOs.

Secreted ACTH was demonstrated in culture medium of Ff-hESC-derived PHOs from day 29 onward (23 pg/mL), with dramatic increases thereafter (Figure 2M). Corticotrophs secrete ACTH on stimulation by corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) (hypothalamic-pituitary axis), with inhibition by glucocorticoids (pituitary-adrenocorticotropic axis). We treated organoids on day 103 with CRH and dexamethasone (DX) (a type of glucocorticoid). ACTH secretion from PHOs increased approximately 3-fold upon CRH treatment (Figure 2N) and decreased by approximately 40% after DX addition (Figure 2O). Ff-hESC-derived PHOs thus appeared able to maintain hormonal homeostasis, not only secreting ACTH but also responding to positive and negative regulators.

Identification of major off-target cells, with purification of pituitary cells, in Ff-hESC-derived PHOs

We assessed suitability for TX of hPSC-derived pituitary tissue by gene expression analysis for the principal off-target cells in Ff-hESC-derived PHOs, examining mRNA levels of key genes associated with differentiation, neural cell lineage, and cell fate choice (heatmap, Figure 3A). We detected NES and SOX11, encoding off-target neural precursor cell markers, in organoids on days 30, 60, and 100. Immunostaining identified Nestin- and SOX11-expressing cells in the inner hypothalamic layer of some organoids on day 103 (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Identification of off-target cells and purification of pituitary cells from Ff-KhES1-derived PHOs

(A) Heatmap, gene expression in pituitary-hypothalamic aggregates derived from Ff-KhES1 cells. Gene expression in undifferentiated Ff-KhES1 cells also shown as control. Gene expression determined qPCR. Row Z scores were calculated for each tissue and plotted as heatmaps.

(B) Immunostained day 103 aggregates, Nestin and SOX11. High-magnification images for Nestin and for SOX11; merged photomicrographs.

(C) Immunostained day 61 aggregates, LHX3, ACTH, and EpCAM.

(D) Schema, intermediate purification protocol.

(E) Representative flow cytometry plots, Ff-KhES1-derived PHOs, day 60.

(F and G) Gene expression analysis results, unsorted cells, day 131 EpCAM+ and EpCAM− spheres sorted on day 60. Gene expression determined by qPCR. Expression of POMC (F), NES, and SOX11 (G).

Scale bars, 200 μm (B and C) and 50 μm (high-magnification image). Data presented as mean ± SEM (n = 6 spheres).

To ensure purity for TX, we reduced off-target cell numbers by isolating pituitary precursor cells from PHOs using the epithelial cell surface and pituitary cell marker EpCAM (Kodani et al., 2022). Unlike E-cadherin, EpCAM does not undergo transient enzymatic degradation, its use maximizes cell sorting yield. In Ff-hESC-derived PHOs, EpCAM was expressed in pituitary epithelial regions (E-cadherin+) harboring pituitary precursor cells (PITX1+, LHX3+) and ACTH-expressing cells (Figures 3C and S3A). To purify pituitary precursor cells, Ff-hESC-derived PHOs were subjected to fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) for EpCAM on days 30, 60, and 100 (Figures 3D, 3E, and S3B). PHOs were dispersed by multiple sequential enzymatic treatments (papain, type I collagenase, and 10× TrypLE Select) and EpCAM+ cells were fractionated using FACS (purity >98%). Sorted EpCAM+ cells were reaggregated and further cultured long term (≥30 days or more) to obtain matured EpCAM+-sorted spheres. Then, on day 131, we performed qPCR analysis of POMC, NES, and SOX11 using unsorted PHOs and of EpCAM+ and EpCAM− spheres sorted on days 30, 60, and 100. At every sorting time point, POMC mRNA levels were higher in EpCAM+-sorted spheres than in EpCAM−-sorted spheres, with POMC expression clearly different between EpCAM+ and EpCAM− cohorts, confirming that EpCAM sorting could purify pituitary cells (Figures 3F, S3C, and S3E). Off-target cell markers NES and SOX11 mRNA levels were high in EpCAM−-sorted spheres and low in EpCAM+-sorted spheres sorted on days 60 and 100 (Figures 3G and S3F). With sorting on day 30, however, off-target cell marker genes were highly expressed not only in EpCAM−-sorted spheres but also in EpCAM+-sorted spheres (Figure S3D), indicating that EpCAM+ spheres sorted on day 30 still contained off-target cells. Interestingly, on day 103, the mean diameter of EpCAM−-sorted spheres gradually surpassed that of EpCAM+ spheres sorted on day 60 (Figures S3G and S3H). These results suggest that FACS using EpCAM can purify pituitary cells from Ff-hESC-derived PHOs and that sorting should be performed after day 60 to reduce off-target cells effectively.

Maturation of EpCAM+ pituitary spheres

We next investigated whether spheres obtained using EpCAM purification matured and functioned like Ff-hESC-derived PHOs. On day 107, Ff-hESC-derived EpCAM+ spheres sorted on day 60 were composed entirely of epithelial cells (EpCAM+/E-cadherin+) and contained large numbers of ACTH-expressing cells (10.8% ± 1.3% of total cells, mean ± SEM, n = 6) (Figure 4A). In contrast, EpCAM−-sorted spheres contained hypothalamic cells (RAX+) and off-target cells (Nestin+, SOX11+), but not pituitary cells (ACTH−/EpCAM−/E-cadherin-) (Figures S4A–S4C). In addition to ACTH-producing cells, Ff-hESC-derived EpCAM+ spheres sorted on day 60 also contained PRL-, GH-, LH-, and FSH-producing cells on days 103 or 107 (Figures 4B–4E).

Figure 4.

Characterization of Ff-KhES1-derived EpCAM+ pituitary spheres sorted on day 60

(A) Immunostained day 107 EpCAM+-sorted spheres, ACTH, EpCAM, and E-cadherin. High-magnification image for ACTH.

(B) Immunostained day 103 EpCAM+-sorted spheres, PRL, EpCAM, and POU1F1.

(C) Immunostained day 103 EpCAM+-sorted spheres, GH (green) and EpCAM.

(D) Immunostained day 103 EpCAM+-sorted spheres, LH and EpCAM.

(E) Immunostained day 107 EpCAM+-sorted spheres, FSH and EpCAM.

(F and G) Electron micrographs (F) and immunoelectron micrographs for ACTH and GH (G) day 201 EpCAM+-sorted spheres and corticotrophs. ACTH granules (10 nm) and GH granules (20 nm, none). Asterisks indicate voids. White dashed line demarcates the cell island.

(H) Long-term ACTH secretion, culture medium, EpCAM+- and EpCAM−-sorted spheres (n = 6–21 experiments).

(I) CRH efficiently induced ACTH secretion in EpCAM+-sorted spheres (n = 6 experiments).

(J) Dexamethasone suppressed ACTH secretion in EpCAM+-sorted spheres (n = 5 experiments).

Scale bars, 200 μm (A), 50 μm (B–E, and high-magnification image), 2 μm (F), and 200 nm (G). Data presented as mean ± SEM. ∗∗∗p < 0.001 using one-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni (H) and paired t test (I and J).

On electron microscopy of EpCAM+ spheres sorted on day 60 and harvested on day 201, hormone secretory granules were numerous (Figures 4F, S4D, and S4E). Immunogold labeling marked most granules for ACTH, none for GH in spheres as well as in PHOs (Figure 4G). Many island-like structures clustered as cell aggregates (Figures 4F, S4D, and S4E), with voids between islands. The surface of each island bore ciliated cells; endocrine cells containing secretory granules filled the center of each spheroid. No necrosis was observed at centers of cell aggregates. FSCs were present in EpCAM+-sorted spheres (Figures S4D and S4E), but were few; they marked on immunostaining for S100 (<0.1% of total cells, Figure S4F) (Horvath and Kovacs, 2002). Immunostaining with SOX2, CD133, and CXADR in EpCAM+ spheres sorted on day 60 and harvested on days 103–107 revealed many SOX2+, SOX2+/CD133+, and SOX2+/CXADR+ cells, but few SOX2+/S100+ pituitary stem cells (Figures S4F–S4I) (Chen et al., 2013; Vankelecom, 2016). Immunostaining also revealed that ACTH-expressing cells and SOX2+ pituitary stem cells or CXADR+ pituitary stem cells were separate populations (Figures S4G and S4J). Purified EpCAM+-sorted spheres thus comprised not only hormone-producing cells but also pituitary stem cells. The slight increase from day 65 to day 103 in mean axial length of EpCAM+ spheres after sorting was provisionally ascribed to inclusion of slow-growing pituitary stem cells (Figures S3G and S3H).

ACTH secretory capacity of EpCAM+ spheres sorted on day 60 continually improved in long-term culture (Figure 4H). By day 103, ACTH secretion rose approximately 2.2-fold after CRH stimulation (Figure 4I) and fell by approximately 50% upon DX treatment (Figure 4J), suggesting that hormone secretion and homeostasis were maintained in EpCAM+-sorted spheres purified from Ff-hESC-derived pituitary organoids. In summary, EpCAM sorting and further culturing produced functional and highly pure 3D pituitary spheres (3D-pituitaries).

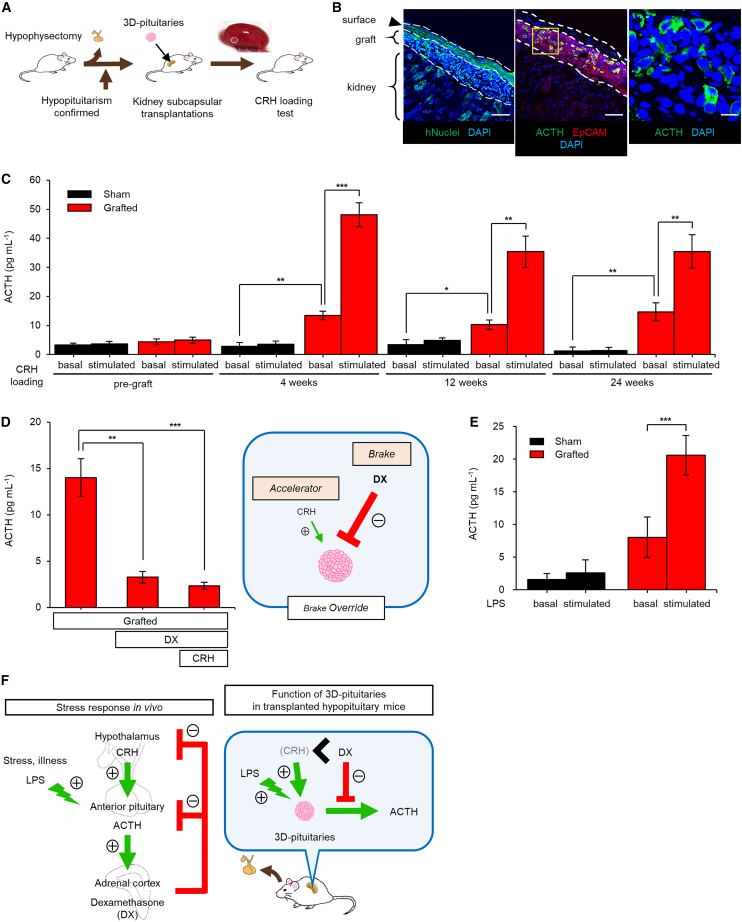

Efficacy of 3D-pituitaries TX into hypopituitary mice

We investigate in vivo function of 3D-pituitaries in hypophysectomized severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) mice (Falconi and Rossi, 1964; Suga et al., 2011). After surgical ablation of the pituitary gland, plasma ACTH concentration after CRH stimulation were measured. Day 107 3D-pituitaries were transplanted under the renal capsule of mice confirmed as hypopituitary (Figure 5A). Immunostaining of kidneys 24 weeks after TX demonstrated hNuclei+ and EpCAM+ Ff-hESC-derived 3D-pituitaries engrafted under the kidney capsule and containing ACTH-expressing cells (Figure 5B). GH-, PRL-, TSH-, LH-, and FSH-expressing cells were also identified, but in very small numbers (Figures S5A–S5D). No tumor formation was observed. The grafts also expressed pituitary stem cell markers, SOX2 and CXADR (Figures S5E and S5F). We evaluated functional efficacy by CRH loading during the 24 weeks before sacrifice (Figure 5C). Four weeks after TX, basal blood ACTH levels were significantly higher in the grafted group than in the sham-operated group (grafted vs. sham, p < 0.01, n = 4, 10). In addition, CRH stimulation induced ACTH secretion. Increased basal ACTH secretion and CRH response were observed until at least 24 weeks after TX (Figure 5C). We infer that increased blood ACTH secreted from grafts reaches host adrenal glands, resulting in glucocorticoid secretion. This may improve host viability by preventing fatal adrenal crisis (Ozone et al., 2016; Suga et al., 2011).

Figure 5.

Survival and function of Ff-KhES1-derived 3D-pituitaries in hypopituitary mice

(A) Schema, TX procedure. Inset, kidney transplanted with 3D-pituitaries; arrowhead, 3D-pituitaries transplanted under renal capsule.

(B) Immunostained allograft (24 weeks), human nuclei (hNuclei), and pituitary markers (ACTH and EpCAM), uniformly under renal capsule. High-magnification image for ACTH.

(C) Blood ACTH levels in sham-operated and grafted mice before and after CRH loading up to 24 weeks after TX. Sham, subcapsular saline injection. Sham, n = 4; grafted, n = 6–10; basal, basal blood ACTH before CRH loading; stimulated, blood ACTH after CRH stimulation.

(D) Dexamethasone treatment suppressed blood ACTH levels in grafted mice. Pretreatment with dexamethasone-suppressed CRH-stimulated ACTH secretion. Grafted, n = 9.

(E) Blood ACTH levels in sham-operated and grafted mice before and after LPS stimulation. Sham, n = 4; grafted, n = 3; basal, basal blood ACTH before LPS injection; stimulated, blood ACTH after LPS stimulation.

(F) Schema, stress response (hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis) in human and in transplanted hypopituitary mice.

Scale bars, 50 μm (B) and 10 μm (high-magnification image). Data presented as mean ± SEM. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001 using Mann-Whitney test (C) (sham vs. grafted) and paired t test (C) (grafted pre vs. post, D and E).

We conducted DX suppression tests in vivo (Figure 5D). Six weeks after TX of Ff-hESC-derived 3D-pituitaries, DX treatment significantly suppressed ACTH secretion. ACTH secretion in DX-pretreated transplanted mice was also almost completely suppressed even after CRH stimulation. Response to negative feedback signaling is key to preventing glucocorticoid excess, because unnecessary ACTH secretion thus stops.

ACTH cells respond to various stimuli other than CRH (Kageyama et al., 2021). On severe stress in healthy subjects (infection, surgery), the pituitary gland secretes large amounts of ACTH to stimulate release of corticosteroids that help buffer against that stress (Luo et al., 2012). We measured blood ACTH response to the mock-infection stress of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) administration (LPS-induced sepsis model) (Stortz et al., 2017). Using an LPS dose that permitted survival in control hypopituitary mice (2.2 μg/kg), 4 weeks after surgery, we stimulated both hypopituitary mice transplanted with 3D-pituitaries and sham-operated hypopituitary mice (Figure 5E). LPS-stimulated ACTH secretion rose significantly in the transplanted group (pre vs. post in grafted group, p < 0.001, n = 4, 3) but not in the sham-operated group. In addition, dose dependence on number of transplanted 3D-pituitaries was observed (Figure S5G). The transplanted 3D-pituitaries thus responded to very small doses of LPS, that is, they could respond to infection stress.

This is the first demonstration that Ff-hESC-derived 3D-pituitaries not only secrete ACTH but also respond appropriately to positive and negative regulators and to LPS-induced mock-infection stress in transplanted mice, with true functionality regulated similarly in vitro and in vivo after TX (Figure 5F).

Discussion

We developed methods of inducing pituitary-hypothalamic tissues from hPSCs under Ff conditions and of purifying pituitary cells for clinical application. By sorting cells from Ff-hPSC-derived PHOs using EpCAM, we reduced off-target cell numbers, acquiring a purified pituitary cell population. PHOs exhibited high ACTH secretory capacity and response to upstream and downstream stimuli that were maintained in purified 3D-pituitaries. When transplanted into hypopituitary mice, engrafted 3D-pituitaries survived for half a year, during which blood ACTH levels were maintained. Furthermore, both positive and negative responses were appropriate for endocrine cells.

Important is that the grafts remained functional for >24 weeks, the longest period reported (Ozone et al., 2016; Zimmer et al., 2016). These features facilitate regenerative medicine use, permitting low doses of transplanted cells infrequently administered. That the transplanted cells responded to CRH and DX, required in clinical practice, suggests regulation in vivo. In the transplanted 3D-pituitaries, negative feedback by DX overrode positive stimulus by CRH, a feature of special note in reducing side effects of ACTH replacement. A few years of excessive glucocorticoid supplementation generally cause serious complications, such as obesity, diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, osteoporosis, and depression (Stewart et al., 2016). 3D-pituitaries, however, even if present only in peripheral tissues, receive steroid feedback through the systemic circulation. Risk of iatrogenic Cushing’s syndrome thus seems low. While PHOs exhibit in vitro inhibitory responses (Kasai et al., 2020; Ozone et al., 2016), maintenance of those responses in vivo after TX, a feature of great clinical importance, is first documented here.

In human clinical practice, “sick days” constitute a rapidly life-threatening and dangerous situation for ACTH-deficient patients. Corticosteroids in abundance are needed to counteract the severe stresses of infection or surgery. In such patients, increased steroid doses—“steroid cover” —are required. However, if steroid cover is delayed, as with loss of consciousness, adrenal crisis and death may occur. Therefore, to recapitulate response to stress is important in pituitary regenerative medicine. With ectopic TX, one can speculate that transplanted 3D-pituitaries were not controlled by CRH secreted from recipient hypothalamus. Hypothalamic CRH normally reaches the adenohypophysis via the hypophyseal portal vein, with very low peripheral blood CRH concentrations unlikely to affect 3D-pituitaries under the renal capsule. All the more provocative, then, that ACTH response to LPS was observed in vivo after TX. Inflammatory stressors such as IL-6 and LIF induced by LPS stimulation reportedly enhance POMC gene transcription and ACTH secretion in pituitary cells (Akita et al., 1995; Bousquet et al., 2000; Pereda et al., 2000), suggesting the possibility of ACTH secretion from pituitary spheres via inflammatory signals in vivo. This phenomenon in LPS-induced pseudoseptic mice, a model of infection stress and inflammatory response, indicates that transplanted cells respond not only to CRH but also to inflammatory stimuli such as those of LPS (Stortz et al., 2017). This suggests that 3D-pituitaries can increase ACTH secretion and reduce acute adrenal insufficiency risk in hypopituitary patients on sick days.

3D-pituitaries also secreted ACTH autonomously both in vitro and after TX in vivo, despite absence of connection with the hypothalamus purportedly necessary for function of the pituitary gland (Matsumoto et al., 2020). The hypothalamus is of course embryologically important in pituitary gland induction. When sorting separated hypothalamus from pituitary on day 30, capacity for hormone secretion remained low thereafter. However, with separation by sorting on day 60, hormone secretion was maintained thereafter, indicating that adjacent hypothalamus is of little significance at day 60, when hormone-producing cells are expressed. Indeed, while pituitary cells secreted ACTH in response to nearby hypothalamic CRH, some basal secretion was observed even when ACTH cells were present alone (Kasai et al., 2020), and ACTH was secreted when pituitary gland elements separated from the PHOs were transplanted beneath the renal capsule (Ozone et al., 2016). Both in vitro and in vivo after TX, 3D-pituitaries showed secretory regulation, indicating that their function is at least partly independent of hypothalamic proximity. As mechanistic details of seemingly autonomous ACTH secretion are unclear, further investigation is needed.

PHOs and 3D-pituitaries contained many pituitary stem cells (SOX2+, CD133+, and CXADR+). To track the dynamics of pituitary stem cells in vitro and in grafts, a new cell line is required that incorporates, for example, a stem cell marker such as SOX2 labeled with a fluorescent protein. If the pituitary stem cells become new hormone-producing cells after TX and are long maintained, to demonstrate further advantages of cells produced as described will be possible, as it will be to identify effects of the pituitary stem cells themselves. Such investigations are planned. On the contrary, Nestin, reportedly a stem cell marker, was not expressed in differentiated pituitary epithelium at day 100. Nestin expression is controversial. Some studies reported that Nestin-expressing cells were 2% in the pituitary of neonatal mice and increased to 20% in adults, while others reported that Nestin-expressing cells were not expressed until mice E18.5 (Gleiberman et al., 2008; Rizzoti, 2010). PHOs at day 100 are considerably younger than at human birth, and Nestin expression may be due to the timing difference. Recent studies using human tissues have reported that Nestin is rarely expressed in pituitary stem cell fractions (Zhang et al., 2020, 2022), suggesting possible species differences.

Our differentiation method induced few FSC-like populations positive for S100. Roles of S100-positive FSCs include stem cells, phagocytosis, intercellular communication, and hormone release (Devnath and Inoue, 2008; Fauquier et al., 2001). In addition, S100-expressing cells in the anterior pituitary can be classified into astrocyte-like, epithelial-like, and dendritic cell-like types (Allaerts and Vankelecom, 2005), and are derived from mesenchymal, vascular, and neural crest systems (Horiguchi et al., 2016). S100-expressing cells thus are heterogeneous and of varying functionalities, but our differentiation method appears inhospitable to such cells.

In this Ff-hPSC protocol, Wnt and TGF-β/Nodal/Activin inhibitors promoted differentiation of non-neural ectoderm and formation of pituitary epithelium. Addition of JNKi improved differentiation efficiency and hormone-secreting capacity. The aggregates contained both LHX3+ cells and ACTH+ cells—nearly 100% vs. ∼30% previously (Kasai et al., 2020). Although inhibition of Wnt and TGF-β/Nodal/Activin signaling is involved in non-neural ectodermal differentiation through suppression of mesoendodermal differentiation (Ealy et al., 2016), how placode induction/JNKi treatment affects 3D-pituitary formation remains unclear. One mechanism could involve IWP2, which inhibits both canonical and non-canonical Wnt pathways, thereby reducing secretion of Wnt proteins. JNKi inhibits the JNK signaling pathway, a non-canonical Wnt pathway. As various upstream stimuli other than Wnt also activate the JNK signaling pathway, multipoint inhibition of the Wnt and JNK pathways may improve hPSC differentiation efficiency. Another mechanism could involve JNKi, which acts to form and to promote the pituitary placode. During early development, the pituitary gland develops as a placode rostral to the non-neural head ectoderm, while the eye also develops as a placode near that of the pituitary gland. JNKi acts on ocular placode formation (p63+ surface ectoderm) via a non-canonical pathway (Kobayashi et al., 2020); it also affects pituitary gland placode formation (LHX3+, E-cadherin+). In the JNK1 knockout mouse iPSCs, nervous-system differentiation is suppressed without decrease in efficiency of induction of ectodermal-cell differentiation (Zhang et al., 2016). We hypothesize that JNKi suppresses differentiation into neurons and thereby relatively improves non-neural epithelial/placode differentiation. To explore mechanisms underlying 3D-pituitary differentiation is in order.

Our strategy provides a new method to produce high-quality pituitary cells suitable for TX therapy. For non-clinical/clinical studies, we will continue to develop manufacturing methods for clinical-grade cell lines, evaluate these lines’ efficacy in animals such as monkeys, and confirm products’ functionality after TX.

Experimental procedures

Resource availability

Corresponding author

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the corresponding author, Hidetaka Suga (sugahide@med.nagoya-u.ac.jp).

Materials availability

All reagents generated in this study are available from the lead contact with a completed Materials Transfer Agreement.

hPSCs

The hESC lines KhES-1 and RAX::Venus, provided by RIKEN BRC, were used according to Japanese government hESC research guidelines. The Ethics Committee of Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine approved all experimental protocols and procedures (approval ES-001). RIKEN BRC provided the human iPSC lines 201B7 and 1231A3.

Differentiation culture of Ff-hPSCs

Before Ff differentiation, preconditioning was performed as described (Kuwahara et al., 2019); hPSCs were treated with 5 μM SB431542 (SB) (Wako) and 300 nM SAG (Cayman) in StemFit medium for 24 h. The SFEBq method was used for cell differentiation. Single cells dissociated from hPSCs using TrypLE Select enzyme were quickly reaggregated using low-cell-adhesion 96-well V-bottomed plates (Sumilon PrimeSurface plates, 10,000 cells/100 μL/well; Sumitomo Bakelite) in a differentiation medium with 20 μM Y-27632, 0.5 μM IWP2 (Wako), 1 μM SB, 1 μM JNK-IB-8 (Merck Millipore), and 100 nM SAG. Differentiation medium (gfCDM; growth factor-free CDM) comprised Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium (Sigma-Aldrich)/Ham’s F12 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) (1:1), GlutaMAX (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 1% chemically defined lipid concentrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and 450 μM 1-thioglycerol (Sigma-Aldrich). Differentiation medium (gfCDM) was supplemented with 5% knockout serum Replacement (KSR). The day when SFEBq culture began was defined as day 0. On day 2, recombinant human BMP4 (R&D), 0.5 nM, and SAG, 700 nM, were added. From days 6 to 30, culture medium was changed by half every 3–4 days. From day 6, concentrations of IWP2, SB, and SAG were maintained, and BMP4 concentration was diluted stepwise. From day 18, aggregates were cultured under high-oxygen conditions (40%). On day 30, aggregates were transferred from 96-well plates to 10-cm Petri dishes. Aggregates were cultured using gfCDM supplemented with 10% KSR from day 30 and 20% KSR from day 51, without IWP2, SB, and SAG.

Cell sorting

As pretreatment, Ff-hPSC-derived aggregates were cultured in 20 μM Y-27632 for 24 h. The pretreated aggregates were dissociated into single cells by treatment with neuron dissociation solution (Wako) at 37°C for 30 min; repeated washing with DMEM/F-12 (Thermo Fisher Scientific); treatment with DMEM/F-12 containing 0.2% collagenase type I (Wako) and 0.1% BSA at 37°C for 30 min with gentle stirring; repeated washing with PBS; treatment with a 10× TrypLE Select solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific) containing 0.2 mg/mL DNase I (Roche) at 37°C for 10 min; and gentle separation by pipetting. The cells were filtered through a 70-μm cell strainer cap (BD Biosciences) and resuspended in sorting buffer (DMEM/F-12) containing 1 mM EDTA, 1% FBS, and 20 μM Y-27632. After incubation with PE-bound anti-EpCAM antibody (1:150) at 4°C for 10 min, the cells were washed twice with sorting buffer and sorted using a FACSAria Fusion cell sorter (BD Biosciences). The data were analyzed using FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences). Selected cells were collected and reaggregated in low-cell-adhesion 96-well V-bottomed plates (10,000 cells/200 μL/well) using gfCDM containing 20 μM Y-27632. From day 3, the medium was replaced with gfCDM without Y-27632 every 3–4 days.

Animals

The Animal Experiments Committee of Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine approved all animal experiments. These were performed in accordance with the Committee’s laboratory animal care and use guidelines.

Male SCID mice (C.B-17/IcrHsd-Prkdcscid, SLC Japan) 7–9 weeks old were used for all TXs. All mice were housed under a 12-h light-dark cycle with free access to food and water. Surgery was performed as described (Ozone et al., 2016; supplemental experimental procedures) with slight modifications.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 3.6.3). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Comparisons between groups were performed using Student’s t test. Comparisons among groups were performed using one-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni’s method or Tukey’s test. Comparisons between sham and grafted mice were performed using the Mann-Whitney U test. A p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Author contributions

H.S., T.N., and A.K. managed the project. S.T., H.S., T.N., and A.K. conceived and designed the study, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. S.T. performed experiments with technical help and advice of Y. Kodani, H.N., Y.S., Y. Tsumura, M. Sakakibara, M. Soen, T.M., H.O., M.K., Y. Kawaguchi, T.M., T. Kobayashi, M. Sugiyama, Y.Y., D.H., and S.I. T.N. designed studies of differentiation culture of Ff-hPSCs and performed related experiments. N.I. performed electron microscopy and analyzed data. K.W. analyzed qPCR data. A.I., M.Y., Y. Takahashi, and S.K. managed the project and analyzed data. Y. Tomigahara, T. Kimura, and H.A. supervised the project. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Tsuzuki for technical assistance, T. Kasai for advice on CRH loading test in vitro, M. Tanaka for assistance with cell-sorting, and C. Ozone, Y. Okuno, H. Takagi, K. Mitsumoto, T. Asano, K. Mizutani, and all members of the Arima laboratory for helpful discussions. We thank Y. Hori for qPCR and members of RACMO for fruitful discussions. This research was supported by the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) (grants JP20bm0404036 and JP22ek0109524, Japan) (to H.S.), the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) FOREST Program (grant JPMJFR200N, Japan) (to H.S.), JST PRESTO (grant JPMJPR19H5, Japan) (to Y.S.), the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) (grants JP20K08859 and JP23K08005, Japan) (to H.S.), (grant JP19K07427, Japan) (to N.I.), Hori Sciences and Arts Foundation (to H.S.), Daiko Foundation (to H.S.), Nitto Foundation (to H.S.), Suzuken Memorial Foundation (to H.S.), Takahashi Industrial and Economic Research Foundation (to H.S.), Nagoya University Hospital Funding for Clinical Research (to H.S.), Sumitomo Pharma Co., Ltd., and Sumitomo Chemical Co., Ltd.

Conflicts of interest

Sumitomo Pharma employs S.T., A.K., K.W., A.I., and M.Y. T. Kimura is a board member of Sumitomo Pharma. Sumitomo Chemical employs T.N., Y. Takahashi, S.K., and Y. Tomigahara. H.S. and H.A. have received research funding from Sumitomo Pharma and Sumitomo Chemical. S.T., H.S., T.N., and A.K. are co-inventors in patent applications related to this study.

Published: June 8, 2023

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stemcr.2023.05.002.

Supplemental information

Data and code availability

Senior authors will promptly review all reasonable requests for considerations of intellectual property or confidentiality. These should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact.

References

- Akita S., Webster J., Ren S.G., Takino H., Said J., Zand O., Melmed S. Human and murine pituitary expression of leukemia inhibitory factor: novel intrapituitary regulation of adrenocorticotropin hormone synthesis and secretion. J. Clin. Invest. 1995;95:1288–1298. doi: 10.1172/JCI117779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allaerts W., Vankelecom H. History and perspectives of pituitary folliculo-stellate cell research. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2005;153:1–12. doi: 10.1530/eje.1.01949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bousquet C., Zatelli M.C., Melmed S. Direct regulation of pituitary proopiomelanocortin by STAT3 provides a novel mechanism for immuno-neuroendocrine interfacing. J. Clin. Invest. 2000;106:1417–1425. doi: 10.1172/JCI11182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M., Kato T., Higuchi M., Yoshida S., Yako H., Kanno N., Kato Y. Coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor-positive cells compose the putative stem/progenitor cell niches in the marginal cell layer and parenchyma of the rat anterior pituitary. Cell Tissue Res. 2013;354:823–836. doi: 10.1007/s00441-013-1713-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis S.W., Ellsworth B.S., Peréz Millan M.I., Gergics P., Schade V., Foyouzi N., Brinkmeier M.L., Mortensen A.H., Camper S.A. Pituitary gland development and disease: from stem cell to hormone production. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 2013;106:1–47. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-416021-7.00001-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devnath S., Inoue K. An insight to pituitary folliculo-stellate cells. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2008;20:687–691. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2008.01716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dincer Z., Piao J., Niu L., Ganat Y., Kriks S., Zimmer B., Shi S.H., Tabar V., Studer L. Specification of functional cranial placode derivatives from human pluripotent stem cells. Cell Rep. 2013;5:1387–1402. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.10.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doi D., Samata B., Katsukawa M., Kikuchi T., Morizane A., Ono Y., Sekiguchi K., Nakagawa M., Parmar M., Takahashi J. Isolation of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived dopaminergic progenitors by cell sorting for successful transplantation. Stem Cell Rep. 2014;2:337–350. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ealy M., Ellwanger D.C., Kosaric N., Stapper A.P., Heller S. Single-cell analysis delineates a trajectory toward the human early otic lineage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:8508–8513. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1605537113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiraku M., Watanabe K., Matsuo-Takasaki M., Kawada M., Yonemura S., Matsumura M., Wataya T., Nishiyama A., Muguruma K., Sasai Y. Self-organized formation of polarized cortical tissues from ESCs and its active manipulation by extrinsic signals. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:519–532. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falconi G., Rossi G.L. Transauricular hypophysectomy in rats and mice. Endocrinology. 1964;74:301–303. doi: 10.1210/endo-74-2-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauquier T., Guérineau N.C., McKinney R.A., Bauer K., Mollard P. Folliculostellate cell network: a route for long-distance communication in the anterior pituitary. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:8891–8896. doi: 10.1073/pnas.151339598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleiberman A.S., Michurina T., Encinas J.M., Roig J.L., Krasnov P., Balordi F., Fishell G., Rosenfeld M.G., Enikolopov G. Genetic approaches identify adult pituitary stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:6332–6337. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801644105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahner S., Spinnler C., Fassnacht M., Burger-Stritt S., Lang K., Milovanovic D., Beuschlein F., Willenberg H.S., Quinkler M., Allolio B. High incidence of adrenal crisis in educated patients with chronic adrenal insufficiency: a prospective study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015;100:407–416. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-3191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horiguchi K., Yako H., Yoshida S., Fujiwara K., Tsukada T., Kanno N., Ueharu H., Nishihara H., Kato T., Yashiro T., Kato Y. S100β-positive cells of mesenchymal origin reside in the anterior lobe of the embryonic pituitary gland. PLoS One. 2016;11:1–18. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0163981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath E., Kovacs K. Folliculo-stellate cells of the human pituitary: a type of adult stem cell? Ultrastruct. Pathol. 2002;26:219–228. doi: 10.1080/01913120290104476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kageyama K., Iwasaki Y., Daimon M. Hypothalamic regulation of corticotropin-releasing factor under stress and stress resilience. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22 doi: 10.3390/ijms222212242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasai T., Suga H., Sakakibara M., Ozone C., Matsumoto R., Kano M., Mitsumoto K., Ogawa K., Kodani Y., Nagasaki H., et al. Hypothalamic contribution to pituitary functions is recapitulated in vitro using 3D-cultured human iPS cells. Cell Rep. 2020;30:18–24.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi Y., Hayashi R., Shibata S., Quantock A.J., Nishida K. Ocular surface ectoderm instigated by WNT inhibition and BMP4. Stem Cell Res. 2020;46 doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2020.101868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodani Y., Kawata M., Suga H., Kasai T., Ozone C., Sakakibara M., Kuwahara A., Taga S., Arima H., Kameyama T., et al. EpCAM is a surface marker for enriching anterior pituitary cells from human hypothalamic-pituitary organoids. Front. Endocrinol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.941166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwahara A., Yamasaki S., Mandai M., Watari K., Matsushita K., Fujiwara M., Hori Y., Hiramine Y., Nukaya D., Iwata M., et al. Preconditioning the initial state of feeder-free human pluripotent stem cells promotes self-formation of three-dimensional retinal tissue. Sci. Rep. 2019;9 doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-55130-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo C., Yang X., Yao L., Jiang L., Liu W., Li X., Wang L. Mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1 expression in macrophages is controlled by lymphocytes during macrophage activation. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2012;29:25–31. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2011.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto R., Suga H., Aoi T., Bando H., Fukuoka H., Iguchi G., Narumi S., Hasegawa T., Muguruma K., Ogawa W., Takahashi Y. Congenital pituitary hypoplasia model demonstrates hypothalamic OTX2 regulation of pituitary progenitor cells. J. Clin. Invest. 2020;130:641–654. doi: 10.1172/JCI127378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa M., Taniguchi Y., Senda S., Takizawa N., Ichisaka T., Asano K., Morizane A., Doi D., Takahashi J., Nishizawa M., et al. A novel efficient feeder-Free culture system for the derivation of human induced pluripotent stem cells. Sci. Rep. 2014;4:3594. doi: 10.1038/srep03594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozone C., Suga H., Eiraku M., Kadoshima T., Yonemura S., Takata N., Oiso Y., Tsuji T., Sasai Y. Functional anterior pituitary generated in self-organizing culture of human embryonic stem cells. Nat. Commun. 2016;7 doi: 10.1038/ncomms10351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereda M.P., Lohrer P., Kovalovsky D., Perez Castro C., Goldberg V., Losa M., Chervín A., Berner S., Molina H., Stalla G.K., et al. Interleukin-6 is inhibited by glucocorticoids and stimulates ACTH secretion and POMC expression in human corticotroph pituitary adenomas. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes. 2000;108:202–207. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-7887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzoti K. Adult pituitary progenitors/stem cells: from in vitro characterization to in vivo function. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2010;32:2053–2062. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzoti K., Lovell-Badge R. Early development of the pituitary gland: induction and shaping of Rathke’s pouch. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2005;6:161–172. doi: 10.1007/s11154-005-3047-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saint-Jeannet J.P., Moody S.A. Establishing the pre-placodal region and breaking it into placodes with distinct identities. Dev. Biol. 2014;389:13–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2014.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider H.J., Aimaretti G., Kreitschmann-Andermahr I., Stalla G.K., Ghigo E. Lancet. 2007;369:1461–1470. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60673-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart P.M., Biller B.M.K., Marelli C., Gunnarsson C., Ryan M.P., Johannsson G. Exploring inpatient hospitalizations and morbidity in patients with adrenal insufficiency. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016;101:4843–4850. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016-2221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stortz J.A., Raymond S.L., Mira J.C., Moldawer L.L., Mohr A.M., Efron P.A. Murine models of sepsis and trauma: can we bridge the gap? ILAR J. 2017;58:90–105. doi: 10.1093/ilar/ilx007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suga H., Kadoshima T., Minaguchi M., Ohgushi M., Soen M., Nakano T., Takata N., Wataya T., Muguruma K., Miyoshi H., et al. Self-formation of functional adenohypophysis in three-dimensional culture. Nature. 2011;480:57–62. doi: 10.1038/nature10637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takuma N., Sheng H.Z., Furuta Y., Ward J.M., Sharma K., Hogan B.L., Pfaff S.L., Westphal H., Kimura S., Mahon K.A. Formation of Rathke’s pouch requires dual induction from the diencephalon. Development. 1998;125:4835–4840. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.23.4835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vankelecom H. Pituitary stem cells: quest for hidden functions. Res. Perspect. Endocr. Interact. 2016;PartF1:81–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q., Mao J., Zhang X., Fu H., Xia S., Yin Z., Liu L. Role of Jnk1 in development of neural precursors revealed by iPSC modeling. Oncotarget. 2016;7:60919–60928. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S., Cui Y., Ma X., Yong J., Yan L., Yang M., Ren J., Tang F., Wen L., Qiao J. Single-cell transcriptomics identifies divergent developmental lineage trajectories during human pituitary development. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:1–16. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19012-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Zamojski M., Smith G.R., Willis T.L., Yianni V., Mendelev N., Pincas H., Seenarine N., Amper M.A.S., Vasoya M., et al. Single nucleus transcriptome and chromatin accessibility of postmortem human pituitaries reveal diverse stem cell regulatory mechanisms. Cell Rep. 2022;38 doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2022.110467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X., Gleiberman A.S., Rosenfeld M.G. Molecular physiology of pituitary development: signaling and transcriptional networks. Physiol. Rev. 2007;87:933–963. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00006.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer B., Piao J., Ramnarine K., Tomishima M.J., Tabar V., Studer L. Derivation of diverse hormone-releasing pituitary cells from human pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell Rep. 2016;6:858–872. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2016.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Senior authors will promptly review all reasonable requests for considerations of intellectual property or confidentiality. These should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact.