Abstract

Biglycan, a small leucine-rich proteoglycan, is involved in collagen fibrillogenesis and also acts as a signaling molecule. While decorin has been considered as the primary small leucine-rich proteoglycan in developing and maintaining tendon structure and mechanics, more recent work using inducible knockdown models suggests that biglycan is involved in tendon homeostasis. The purpose of the study was to determine the role of biglycan in tendon homeostasis to maintain mechanical and structural integrity in aged mice. Aged (485 days old) female Bgn+/+ control (WT, n=16) and 16 bitransgenic conditional Bgnflox/flox mice (I-Bgn−/−, n=16) with a tamoxifen inducible Cre (driven by ROSA) were utilized. After biglycan knockdown, the transgenic model demonstrated effective knockdown of the target gene without any compensation from other SLRPs or type I collagen. Patellar tendon cellularity was not modified after biglycan knockdown. However, biglycan knockdown had an impact on collagen fibrillogenesis with a higher percentage of small diameter fibrils (25-45nm) and a lower percentage of medium size fibrils (150-165nm) in I-Bgn−/− tendons. Biglycan knockdown also induced a reduction in the midsubstance modulus and maximum stress compared to wild type. Stress relaxation was reduced at 4% strain in I-Bgn−/− tendons but no changes were observed in dynamic modulus and tan delta. As in mature tendons (120 days old), this study showed significant effects of biglycan knockdown on mechanical and structural properties of aged tendons only 30 days after knockdown. These data suggest that biglycan has a major role in maintaining homeostasis in aged tendon.

Keywords: biglycan, small leucine-rich proteoglycan, tendon, aging

1. Introduction

Tendons are dense connective tissues allowing the transmission of forces between muscles and bones. To fulfill this role, tendons have a highly organized matrix mainly composed of type I collagen. However, other constituents of the extracellular matrix are critical to the homeostasis and mechanical function of the tendon. Among the non-collagenous components of the tendon matrix, biglycan (Bgn), a small leucine-rich proteoglycan (SLRP), has been implicated in regulation of fibrillogenesis [1, 2]. Biglycan has also been identified as a signaling molecule and a modulator of growth factors and cytokines through its interactions with TGFβ, TNFα or BMP2, −4 and −6 [3].

Conventional global knockout models targeting class I SLRPs, decorin and biglycan, indicated that decorin is the primary SLRP in developing and maintaining tendon structure and mechanics, while knockout of biglycan had minimal effect on these parameters [4,5]. However, more recent work using inducible knockdown models suggests that biglycan is involved in tendon homeostasis since its deletion in adult mice (120 days old) led to reduced viscoelastic and dynamic mechanical properties and altered structural parameters only 30 days after knockdown [6]. The benefit of this inducible model compared to the global knockout is removing the confounding variable of altered developmental processes and consequently isolate the effect of the targeted protein on homeostasis.

While aging is identified as a risk factor for tendon disorders by inducing changes in tendon biology and biomechanical properties [7, 8], the mechanisms leading to the age-related changes are not well understood. In the context of tendon injury, biglycan knockout had an age-dependent effect with an inferior recovery of viscoelastic properties in tendons from older mice [9]. However, the role of biglycan in maintaining tendon homeostasis during aging is not known. Thus, the purpose of the study was to determine the role of biglycan in tendon homeostasis to maintain mechanical and structural integrity in aged mice. We hypothesized that deletion of Bgn in aged mice will result in reduced tendon mechanical properties and alterations in the fibrillar structure.

2. Methods

2.1. Animals

Female Bgn+/+ control (WT, n=16) and bitransgenic conditional Bgnflox/flox mice (I-Bgn−/−, n=16) with a tamoxifen (TM) inducible Cre, (B6.129-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1(cre/ERT2)Tyj/J, Jackson Labs) were utilized (IACUC approved). Cre excision of the conditional alleles was induced in aged mice (485 days) via three consecutive daily intraperitoneal injections of tamoxifen (112mg/kg). WT mice received the same injections of tamoxifen as control. Mice from both groups were euthanized 30 days after tamoxifen treatment, at 515 days old.

2.2. Gene expression

At the time of sacrifice, whole mouse patellar tendons were isolated, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until time of assay. The tendons were isolated from the surrounding tissue and patella. After crushing with a pestle, total RNA was extracted using the Direct-zol RNA Microprep kit (Zymo Research, R2062), and cDNA was synthesized using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (#4368814, ThermoFisher). The resultant cDNA underwent 15 cycles of pre-amplification with selected Taqman Gene Expression Assays (Preamp Master Mix, PN 100-5744, Fluidigm). Pre-amplified cDNA was used to perform a real-time PCR with TaqMan™ Fast Advanced Master Mix according to manufacturer’s protocols (#4444557, ThermoFisher). Gene expression of the SLRPs Bgn (Mm01191753_m1), Dcn (Mm00514535_m1), Lum (Mm01248292_m1), Fmod (Mm00491215_m1) and Kera (Mm00515230_m1), as well as Col1a1 (Mm00801666_g1), were assessed. Abl1 was used as the housekeeping gene (Mm00802029_m1). Resultant cycle threshold (Ct) values were normalized to the invariant controls (Abl1) and expressed as 2ΔCt (n=4/group).

2.3. Histology

For histological analysis, the knee joint was removed by cutting through the femur and tibia at the time of sacrifice. The knee was flexed to 90°, placed into a cassette, fixed in formalin, and processed using standard paraffin histological techniques. Samples were embedded in paraffin and 7 µm longitudinal sections of the patellar tendon were obtained and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). In each group, we studied 4 tendons, each taken from a different mouse. For the analysis, 2 sections per tendon were included (8 sections/group). On each section, 2 ROI were selected in the midsubstance and one in the tibial insertion area. The same sections were used for both regions. Cellularity and cell nuclear shape (width/length ratio) were assessed in each ROI using ImageJ.

2.4. Biomechanics

After sacrifice, the mice were frozen at −20°C until the day of the experiment. On the day of testing, mice were thawed 30 minutes before dissection. The patellar tendon-bone complex from one limb of each animal was dissected and prepared for biomechanical testing (n=12/group). After dissection, stain lines were applied to allow optical tracking (Verhoeff’s stain). For the patellar tendon, the gauge length is approximately 3mm so the stain lines were placed at the tibial insertion and 1, 2, and 3mm from the insertion site. The insertion region was termed as the region between the first and the second line and the midsubstance between the second and the third line. Cross-sectional area was measured using a custom laser device. The tibia was potted in polymethyl methacrylate and the patella was gripped in a custom fixture. Then, the tendon was mounted within a mechanical testing machine into a phosphate buffered saline bath at 37°C (5848, Instron; Norwood, MA). After a pre-load at 0.03N, the applied testing protocol consisted of 10 cycles of preconditioning (sinusoidal oscillations with 0.5% strain amplitude centered at 1% strain), 5 minutes of recovery at 0% strain, stress relaxations at 3, 4, and 5% strains held for 10 minutes followed by frequency sweeps at 0.1, 1, 5, and 10Hz, rest for 5 minutes, and a quasi-static ramp to failure (0.1% strain per second). Dynamic collagen fiber realignment, defined as the circular variance of collagen alignment at a specific strain normalized within samples to the circular variance of alignment at the beginning of the ramp to failure, was quantified in the insertion and the midsubstance region using cross-polarization imaging [6]. Percent relaxation was quantified for each stress-relaxation. Dynamic modulus and phase angle delta were computed for each frequency sweep at each strain level. Fiber realignment, elastic modulus, and failure stress were assessed during the ramp-to-failure. Elastic modulus was calculated using optical strain tracking.

2.5. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

Patellar tendons were analyzed using TEM. Samples were fixed in situ using standard methods [6; 10–11]. Post staining with 2% aqueous uranyl acetate followed by 1% phosphotungstic acid, pH 3.2, was utilized for contrast enhancement. Cross sections through the midsubstance of the patellar tendons were examined at 80 kV using a JEOL 1400 transmission electron microscope. Images were digitally captured within the injury region at an instrument magnification of ×60,000 (Orius widefield sidemount CCD camera) at a resolution of 3648 × 2672. Then, collagen fibril diameter was measured using a custom Matlab code (Matlab, R2020a) and fibril density was determined using the total number of fibrils within the ROI normalized for area. Ten images from each tendon were blindly analyzed and tendons were taken from 4 mice of each phenotype.

2.6. Statistics

Student’s t-tests were used to compare cellularity between the two genotypes and Mann-Whitney tests were used to compare nuclear aspect ratios and gene expression. Fibril diameter distributions were compared using a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Student’s t-tests were used to compare groups for mechanical properties. A two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc was used to compare collagen realignment across genotypes and subsequent strains. The threshold for significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Gene expression of SLRP and type I Collagen

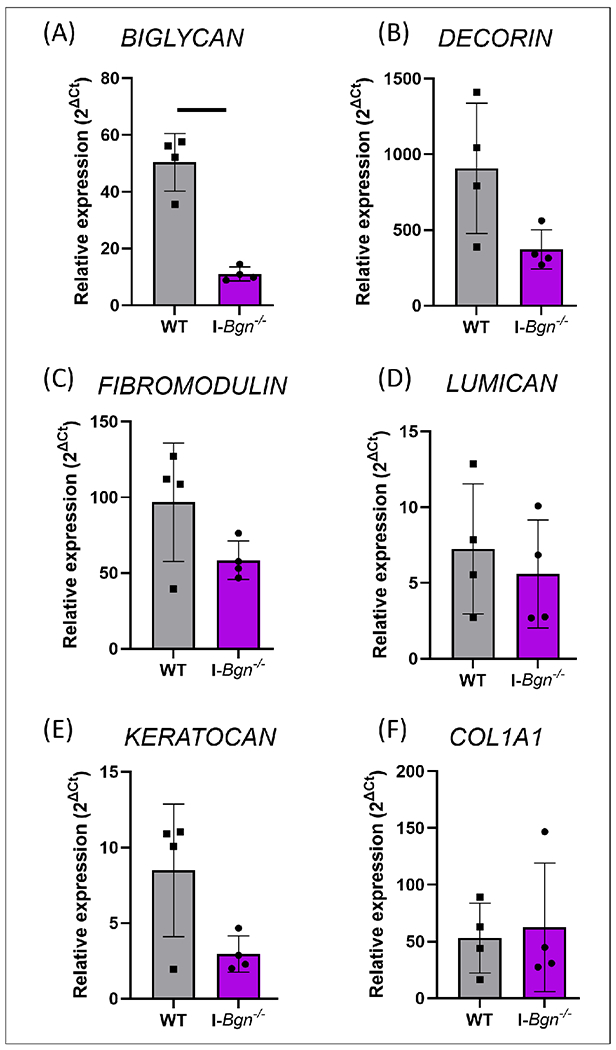

As expected, biglycan expression was reduced in I-Bgn−/− tendons (Fig. 1A). Expression of other SLRPs was also measured to determine whether compensatory up-regulation mechanisms existed after biglycan knockdown. There were no changes in expression of decorin (Fig. 1B) or of class II SLRPs fibromodulin, lumican and keratocan (Fig. 1C,D,E). Type I collagen expression was also not altered in the I-Bgn−/− tendons (Fig. 1F). Overall, the transgenic model demonstrated effective knockdown of the target gene without any compensation from other SLRPs or type I collagen.

Figure 1. Gene expression of class I and II SLRPs and type I collagen.

Gene expression data showed knockdown of biglycan with no compensatory effects of class I and II SLRPs or type I collagen. WT= wild type. Solid bar represents p < 0.05.

3.2. Histology

Histological analysis did not reveal any gross differences between the two genotypes (e.g., no insertion calcification, no differences in tendon thickness). No changes in cellularity were seen after biglycan knockdown in the midsubstance or in the tibial insertion region. However, a significant difference in nuclear aspect ratio was observed only in the tibial insertion area, with a lower ratio in the I-Bgn−/− tendons indicating a more spindle-like nuclear shape (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Analysis of cellularity and cell shape.

There were no differences in cellularity between genotypes, while cell shape was different between genotypes with a lower nuclear aspect ratio in I-Bgn−/− tendons in the insertion area. WT= wild type. Solid bar represents p < 0.05.

3.3. Biomechanics

WT and I-Bgn−/− tendons had similar cross-sectional area (Fig. 3A). Analysis of quasi-static mechanics also revealed a reduction in the midsubstance modulus and maximum stress in I-Bgn−/− tendons compared to WT (Fig. 3C), while insertion modulus was unaffected (Fig. 3D). I-Bgn−/− tendons also demonstrated decreased stress relaxation compared to WT at each strain level, although the effect reached statistical significance only at 4% strain (Fig. 4). This effect on stress relaxation indicates a slight reduction in long-term time-dependent behavior in I-Bgn−/− tendons that is most prominent near the transition region of the stress-strain curve. Dynamic modulus and phase shift at each strain level and frequency were unaffected by genotype (Fig. S1). Collagen fiber realignment revealed similar behaviors between WT and I-Bgn−/− tendons in the midsubstance (Fig. 5A). Specifically, increased realignment occurred between 1% and 3% strain and 3% and 5% strain in both groups, with no changes in realignment occurring between 5% and 7% strain. Realignment behavior diverged in the insertion region between WT and I-Bgn−/− tendons with both genotypes showing increased realignment between 1% and 3% strain, but only WT tendons continuing to increase in realignment between 3% and 5% strain (Fig. 5B). Additionally, at 5% and 7% strain, the magnitude of realignment in I-Bgn−/− tendons was less than what was observed in WT tendons (Fig. 5B).

Figure 3. Quasi-static mechanical properties of WT and I-Bgn−/− tendons.

Maximum stress and midsubstance modulus were reduced after biglycan knockdown. WT= wild type. Solid bars represent p < 0.05.

Figure 4. Stress relaxation of WT and I-Bgn−/− tendons.

I-Bgn−/− tendons demonstrated decreased relaxation during a stress relaxation at 4% strain compared to WT. WT= wild type. Solid bar represents p < 0.05.

Figure 5. Collagen fiber realignment across the ramp-to-failure.

While collagen fiber realignment revealed identical behaviors between WT and I-Bgn−/− tendons in the midsubstance, realignment behavior was different in the insertion with an inferior collagen fiber realignment in I-Bgn−/− tendons at 5 and 7% strain. WT= wild type. Solid bar represents p < 0.05.

3.4. Transmission electron microscopy

Finally, tendon structure was analyzed using TEM. No qualitative changes to collagen fibril shape were apparent after biglycan knockdown in aged tendons. However, the fibril diameter distributions were different between the two genotypes with a higher percentage of small diameter fibrils (25-45nm) and a lower percentage of medium size fibrils (150-165nm) in I-Bgn−/− tendons (Figure 6). The average fibril diameter and fibril density were not different between the 2 groups.

Figure 6. Representative TEM images (A) and (C) and fibril diameter distributions in percentages within the midsubstance (B) and (D).

I-Bgn−/− tendons had more smaller and fewer medium sized fibrils compared to WT. The average fibril diameter and fibril density were not different between the 2 groups. WT= wild type.

4. Discussion

In this study, the role of biglycan in tendon homeostasis in the context of aging was explored by studying the impact of its knockdown on the structural and mechanical properties of aged patellar tendons. Consistent with our hypothesis, knockdown of biglycan in aged mice resulted in reduced tendon quasi-static mechanical properties 30 days after the knockdown. I-Bgn−/− tendons revealed reduced midsubstance modulus, reduced max stress, decreased stress relaxation, and a lesser degree of realignment in the insertion region of the tendon. These results are not related to a reduction in the expression level of biglycan during aging since it was shown that its expression remained stable at adult ages between 150 and 570 days [12]. These mechanical effects of biglycan knockdown observed here are similar to the effects of aging on patellar tendon mechanics that were reported in prior work, suggesting that biglycan knockdown exacerbates the effects of aging on the mechanical properties of patellar tendons. [12].

In conventional Bgn−/− models, linear modulus, stress relaxation or collagen fiber realignment were not altered in aged (570 days) supraspinatus tendons compared to WT tendons [13]. However, as biglycan was absent during the lifetime of the mice, compensatory mechanisms could have overshadowed the effects of the knockout. In contrast, the mouse model used in this study demonstrated effective knockdown of the target gene without any compensation from other SLRPs and without any developmental changes. This allowed analysis of the role of biglycan in the homeostasis of aged tendon without the confounding effects of altered developmental and growth processes.

Biglycan knockdown induced changes in the fibril diameter distribution. These structural changes are likely due to the role of biglycan in collagen fibrillogenesis and may have caused the inferior mechanical properties of aged I-Bgn−/− tendons as demonstrated for decorin [14]. Given the short delay between the knockdown and the analysis, the main mechanism likely involved in fibrillogenesis alterations would be related to a disturbance in the fusion of the fibers. Proteoglycans are known to directly bind to collagen fibrils, mostly via the core protein but also through the GAG chains, thereby regulating collagen fibrillar diameter, intermolecular cross-linking, and aggregation into thicker bundles [15]. In addition, decorin and biglycan are known to play important roles in stabilizing mature collagen fibrils by preventing lateral fusion of smaller diameter fibrils. However, in contrast to P120 mice, no increase in fibril diameter was observed in I-Bgn−/− tendons even as the distribution of fibril diameters differed between the two groups. This may suggest that biglycan does not participate in this regulation in the aged tendon matrix. This conclusion is also supported by previous data from aged biglycan-null tendons which also did not exhibit an increase in fibril diameter compared to WT [Ref 12].

Similar to the effect observed in tendons of mature mice (120 days) [6], biglycan knockdown induced changes in the nuclear aspect ratio in the insertion region. This could be related to the role of biglycan in regulating tendon stem/progenitor cells (TSPC) as biglycan and fibromodulin have been identified as two critical components that organize the TSPC niche [16]. Evidence suggested that biglycan plays a major role in the maintenance of this niche by regulating tendon progenitor differentiation, and balance of cytokines and growth factors. Bgn0/− Fmod−/− mice exhibited impaired differentiation and function of TSPCs and changes in TSPC niche–associated ECM composition may alter the fate of TSPCs through an imbalance of certain cytokines and growth factors in the ECM [16]. In addition, disruption of the tissue niche in tendon can result in a switch from homeostasis to degenerative matrix remodeling [17]. We speculate that inactivation of biglycan could disrupt the tissue niche, and this may have led to a switch from homeostasis to a degenerative state inducing an alteration of mechanical properties (decreased maximum stress and modulus) in I-Bgn−/− tendons. Future work will be needed to explore the impact of biglycan knockdown on tendon cell phenotype and functions in the context of homeostasis and aging. Collagen fiber realignment was also delayed in the insertion region suggesting a dysfunction of the collagen network in this area.

We acknowledge that the study has some limitations. We did not assess biglycan content at the protein level. In explant cultures of tendon, the T½ of radio-labelled biglycan was approximately 20 days [18]. However, for the goal of this study, we were primarily interested in the change in new expression following the knockdown. Previous data using the same mouse model showed that, 24 days after the tamoxifen knockdown, biglycan protein expression was drastically reduced [19]. In addition, in another study using 120-days-old mice [6], a delay of 30 days after the knockdown was sufficient to observe changes in tendon structural and mechanical properties [6]. However, it remains possible that residual biglycan has reduced the impact of the knockdown on tendon structural and mechanical properties. For this study, we used 16-month-old mice as aged mice because working with this colony, we were concerned that the mice would not survive reliably to 18 months or longer. Finally, as the knockdown was not tissue-specific, it could have influence other tissues such as muscles.

5. Conclusion

As in mature tendons (120 days old) [6], this study showed significant effects of biglycan knockdown on structural and mechanical properties of aged tendons (485 days old) only 30 days after knockdown. While among SLRPs, decorin is considered as the primary regulator of tendon homeostasis at maturity, these data suggest that biglycan has a major role in maintaining homeostasis in aged tendon. Future studies using the inducible model will determine the impact of biglycan knockdown on tendon healing in mature and aged tendons.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary figure S1. Dynamic modulus and tan delta at 3, 4, and 5% stains. I-Bgn−/− and WT tendons had similar dynamic modulus and tan delta. WT= wild type.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge financial support from NIH/NIAMS R01AR068057, P30AR069619. We also acknowledge David E. Birk and Sheila M. Adams for their contribution to the TEM images.

Footnotes

Authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- [1].Ansorge HL, Adams SM, Birk DE, Soslowsky LJ. 2011. Mechanical, compositional and structural properties of the post-natal mouse Achilles tendon. Ann Biomed Eng 39(7):1904–1913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Dunkman AA, Buckley MR, Mienaltowski MJ, et al. 2014. The tendon injury response is influenced by decorin and biglycan. Ann Biomed Eng 42(3):619–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Nastase MV, Young MF, Schaefer L. 2012. Biglycan: a multivalent proteoglycan providing structure and signals. J Histochem Cytochem 60(12):963–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Dourte LM, Pathmanathan L, Mienaltowski MJ, et al. 2013. Mechanical, compositional, and structural properties of the mouse patellar tendon with changes in biglycan gene expression. J Orthop Res 31(9):1430–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Gordon JA, Freedman BR, Zuskov A, et al. 2015. Achilles tendons from decorin- and biglycan-null mouse models have inferior mechanical and structural properties predicted by an image-based empirical damage model. J Biomech 48(10):2110–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Beach ZM, Bonilla KA, Dekhne MS, et al. 2022. Biglycan has a major role in maintenance of mature tendon mechanics. J Orthop Res 40(11):2546–2556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Lindemann I, Coombes BK, Tucker K, et al. 2020. Age-related differences in gastrocnemii muscles and Achilles tendon mechanical properties in vivo. J Biomech 112:110067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Korcari A, Przybelski SJ, Gingery A, Loiselle AE. 2022. Impact of aging on tendon homeostasis, tendinopathy development, and impaired healing. Connect Tissue Res 28:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Dunkman AA, Buckley MR, Mienaltowski MJ, et al. 2014. The injury response of aged tendons in the absence of biglycan and decorin. Matrix Biol 35:232–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Robinson KA, Sun M, Barnum CE, et al. 2017. Decorin and biglycan are necessary for maintaining collagen fibril structure, fiber realignment, and mechanical properties of mature tendons. Matrix Biol 64: 81–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Birk DE, Zycband EI, Woodruff S, et al. 1997. Collagen fibrillogenesis in situ: Fibril segments become long fibrils as the developing tendon matures. Dev Dyn 208(3):291–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Dunkman AA, Buckley MR, Mienaltowski MJ, et al. 2013. Decorin expression is important for age-related changes in tendon structure and mechanical properties. Matrix Biol 32(1):3–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Connizzo BK, Sarver JJ, Birk DE, et al. 2013. Effect of age and proteoglycan deficiency on collagen fiber re-alignment and mechanical properties in mouse supraspinatus tendon. J Biomech Eng 135(2):021019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Zhang G, Ezura Y, Chervoneva I, et al. 2006. Decorin regulates assembly of collagen fibrils and acquisition of biomechanical properties during tendon development. J Cell Biochem 98(6):1436–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Kram V, Shainer R, Jani P, et al. 2020. Biglycan in the Skeleton. J Histochem Cytochem 68(11):747–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Bi Y, Ehirchiou D, Kilts TM, et al. Identification of tendon stem/progenitor cells and the role of the extracellular matrix in their nich. Nat Med 13(10):1219–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Wunderli SL, Blache U, Beretta Piccoli A, et al. 2020. Tendon response to matrix unloading is determined by the patho-physiological niche. Matrix Biol 89:11–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Samiric T, Ilic MZ, Handley CJ. 2004. Large aggregating and small leucine-rich proteoglycans are degraded by different pathways and at different rates in tendon. Eur J Biochem 271(17):3612–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Robinson KA, Sun M, Barnum CE, et al. 2017. Decorin and biglycan are necessary for maintaining collagen fibril structure, fiber realignment, and mechanical properties of mature tendons. Matrix Biol 64:81–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary figure S1. Dynamic modulus and tan delta at 3, 4, and 5% stains. I-Bgn−/− and WT tendons had similar dynamic modulus and tan delta. WT= wild type.