Abstract

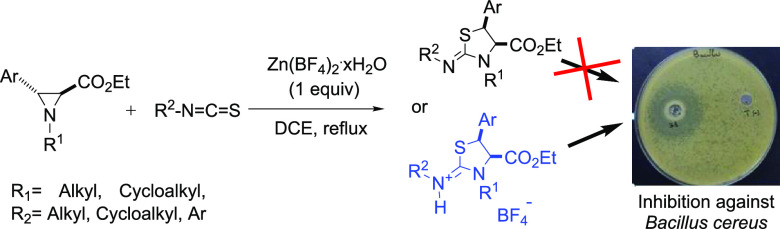

Cis-2-iminothiazolidines and cis-thiazolidine-2-iminium tetrafluoroborates were successfully produced from trans-N-alkyl aziridine-2-carboxylates and phenyl/alkyl isothiocyanates mediated by zinc tetrafluoroborate in refluxing DCE. Reactions were performed via a complete regio- and stereoselective process to give the title iminothiazolidines and cis-thiazolidine-2-iminium salts in moderate to good yields (35 to 82%) with a wide substrate scope. In addition, the antibacterial activity evaluation of these compounds, as well as the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) determination, revealed that only four cis-thiazolidine-2-iminium salts showed growth inhibition against Bacillus cereus.

Introduction

Iminothiazolidines are an interesting class of molecules, which have been widely studied due to their diverse fields of application. Indeed, a large number of these five-membered heterocyclic systems play an important role in medicinal chemistry and exhibit significant physiological activities.1 They are used as anti-inflammatory,2 antihypertensive,3 anti-Alzheimer,4 and antidepressant agents.5 They serve as progesterone receptor-binding agents6 and act as nitric oxide synthase (NOS) inhibitors.7 Some of them find applications as γ-radioprotective agents,8 and others are used in agriculture as pesticides.9 Moreover, tetramisole, a bicyclic iminothiazolidine, was found to be a competent enantioselective acylation catalyst.10 These heterocycles are also useful intermediates in the synthesis of compounds such as iminothiazolines, possessing a wide range of biological and pharmaceutical activities.11

Due to the wide variety of their applications, several strategies have been developed for the synthesis of iminothiazolidines. For instance, the synthesis of these five-membered aza-heterocycles are reported from the rhodium-catalyzed reaction of thiazolidine with carbodiimides,12 reaction integrating an iron-catalyzed nitrene transfer and domino ring-opening cyclization,13 BF2OTf·OEt2-catalyzed ring expansion of phenylthiranes with arylcarbodiimides,14 a base-mediated [3 + 2] annulation involving substituted thioureas and allylic bromides,15 and by the ring transformation of 2-(thiocyanomethyl)aziridines upon treatment with titanium(IV) chloride11 or using a silica–water system and potassium thiocyanates.16

On the other hand, one of the classical methods for the synthesis of iminothiazolidines involves the reaction of aziridines and isothiocyanates. This reaction has been studied using ZnCl2-, BF3·OEt2-, FeCl3-, Al(salen)Cl-, pyrrolidine-, Bu3P-, and Pd(II)-based systems as catalysts or stoichiometric reagents.17 Although a variety of strategies leading to C4 or C5 monosubstituted 2-iminothiazolidines have been developed, compounds obtained from nonactivated aziridines possessing 4,5-two vicinal stereogenic centers have rarely been reported.18

Results and Discussion

Chemistry

In a previous publication, we described the ring expansion of trans-aziridine-2-carboxylates into trans-imidazolidine-2-thiones as the major products in the absence of a catalyst, via a complete regio- and stereoselective process (Scheme 1a).19 Herein, we show that in the presence of a Lewis acid, the behavior of aziridine-2-carboxylates and isothiocyanates is different. In fact, utilizing zinc tetrafluoroborate as a mediator in these reactions leads exclusively to cis-2-iminothiazolidines or cis-thiazolidine-2-iminium tetrafluoroborates (Scheme 1b).

Scheme 1. Ring Expansion of trans-N-alkyl Aziridine-2-carboxylates with Isothiocyanates in Our Previous Work (a) and This Work (b).

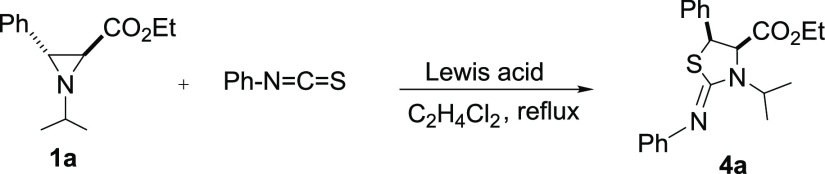

In order to explore the optimum reaction conditions, we chose the reaction of phenyl isothiocyanate with trans-N-isopropylaziridine-2-carboxylate 1a as the model substrate. Several metal halides were tested, and few of them were able to catalyze this reaction with varying degrees of success. When aziridine and isothiocyanate were mixed in the presence of a catalyst (0.1 equiv), there was no reaction at room temperature in all cases with the recovery of starting materials. Under the reflux of DCE, Lewis acids ZnCl2, BF3·OEt2, and Cu(OTf)2 did not catalyze the reaction at all, with the formation of a complex mixture of unknown compounds. However, Zn(BF4)2·xH2O gave 25% of 2-iminothiazolidinones 4a under the same conditions. Catalysts ZnBr2, Cu(CF3SO3)2, and Cu(BF4)2·xH2O also led to this transformation but with a lower activity. On the basis of the obtained results, Zn(BF4)2·xH2O was found to be the most effective catalyst. Switching the solvent from DCE to toluene or nitromethane using this catalyst did not improve the yield of product 4a. Increasing the amount of Zn(BF4)2·xH2O from 0.1 to 0.5 equiv hardly improved the reaction yield. When larger amounts of Cu(BF4)2·xH2O (1 equiv) or Zn(BF4)2·xH2O (1 equiv) were used, the reaction afforded the desired cis-2-iminothiazolidinone 4a in good to excellent yields, respectively. This is consistent with the results of Stoltz and co-workers who showed that a stoichiometric amount of Lewis acid is required to allow the full conversion of the starting products in cycloaddition reactions with heterocumulenes.17a,17h It is important to note that several reactions have been described in which zinc tetrafluoroborate proved to be a suitable catalyst for various useful transformations and that a better catalytic activity of Zn(BF4)2·xH2O compared to other Lewis acids was mentioned in the works of Chakraborti and co-workers20 and Majee and co-workers.21

The results obtained are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Optimization of Reaction Conditions.

| entry | Lewis acid (x equiv) | solvent | t (h) | 2a | yield (%) 3a | 4a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ZnBr2 (0.1) | DCE | 2 | – | – | 13 |

| 2 | ZnCl2 (0.1) | DCE | 2 | – | – | – |

| 3 | BF3·OEt2 (0.1) | DCE | 2 | – | – | – |

| 4 | Cu(OTf)2 (0.1) | DCE | 2 | – | – | – |

| 5 | Cu(CF3SO3)2 (0.1) | DCE | 4 | – | – | 12 |

| 6 | Zn(BF4)2·xH2O (0.1) | DCE | 3 | – | – | 25 |

| 7 | Zn(BF4)2·xH2O (0.5) | DCE | 3 | – | – | 43 |

| 8 | Zn(BF4)2·xH2O (0.1) | Toluene | 3 | 20 | 20 | trace |

| 9 | Zn(BF4)2·xH2O (0.1) | CH3NO2 | 3 | – | – | trace |

| 10 | Cu(BF4)2·xH2O (1) | DCE | 3 | – | – | 60 |

| 11 | Zn(BF4)2·xH2O (1) | DCE | 3 | – | – | 90 |

As can be seen from Table 1, there is a clear superiority of Zn(BF4)2·xH2O which proved to be the most effective Lewis acid used for this reaction. The cyclic structure of 4a was established by IR and 1D NMR techniques. The presence of the C=NR group was confirmed by the appearance of a strong band at approximately 1630 cm–1 in the IR spectrum and by a 13C NMR resonance signal for the same group at 157.98 ppm, and no C=S signal was observed in our case. The cis-stereochemistry of 4a was unambiguously confirmed from the coupling constant between the C4 and C5 protons, with Jcis values of ∼7.9 Hz (Jtrans = 3–4 Hz), which is in agreement with those reported in the literature for cis-iminothiazolidine.17b

Attempts to obtain crystals of iminothiazolidine 4a were unsuccessful. Instead, we recovered traces of a secondary product in one of the 4a tests, and crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction studies were obtained. However, the determination of the crystalline structure revealed that this product corresponds to a tetrafluoroborate of thiazolidine-2-iminium 4a’ with a cis-stereochemistry around the C=N bond (Figure 1). This very interesting result may indirectly confirm the structure of compound 4a and its cis-stereochemistry, which was further evidenced by the conversion of 4a’ to 4a under basic conditions (K2CO3).

Figure 1.

ORTEP view of compound 4a’ (CCDCN° 2189951).

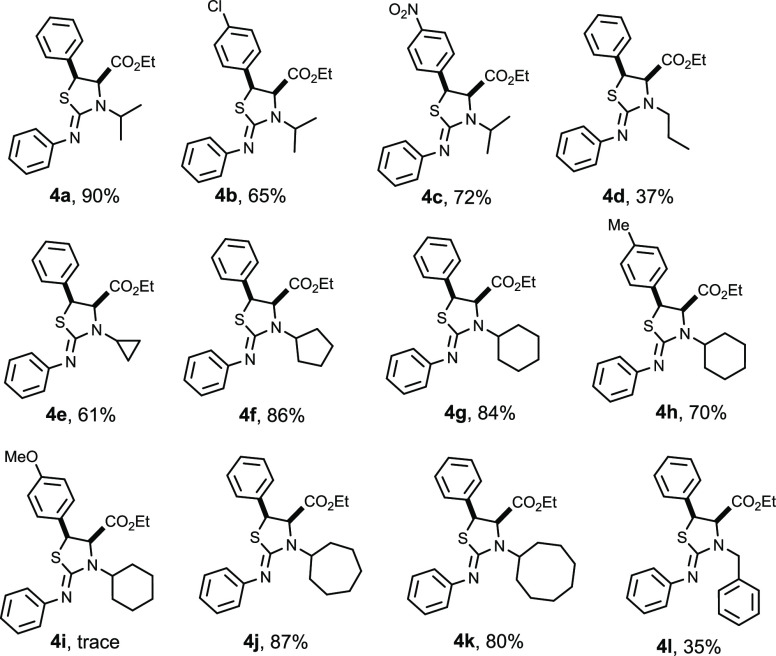

With the optimized reaction conditions in hand, we next evaluated the generality and scope of the methodology for the synthesis of cis-iminothiazolidines 4 via the cycloaddition of N-alkyl aziridine-2-carboxylates and N-aryl isocyanates mediated by zinc tetrafluoroborate (Table 2).

Table 2. Scope of the Reaction of trans-N-alkyl Aziridine-2-carboxylates with N-aryl Isothiocyanates.

The results reported in Table 2 showed that good yields are always obtained (65–90%), except for 4i (Ar = p-MeOC6H4) where the reaction proved unsuccessful, affording trace amounts of the desired product. In contrast, aziridine reactivity is not affected by the electronic influence of some aromatic substituents such as NO2, CH3 and Cl. In the case of 1l, the reaction gave the expected product in a low yield (35%). This reflects the steric effect of the benzyl group in N-alkyl aziridine on the reaction outcome.

The successful ring-expansion reactions of trans-N-alkyl aziridine-2-carboxylates in the presence of N-aryl isothiocyanates inspired us to further examine the electronic effects on the reaction when the isothiocyanate aryl group was replaced with an alkyl or cycloalkyl group. Surprisingly, in contrast to the N-aryl-substituted isothiocyanates, N-ethyl and N-cyclohexyl isothiocyanates reacted with N-alkyl aziridines 1 under the same reaction conditions to yield cis-thiazolidine-2-iminium tetrafluoroborates 5 as the sole products. This unexpected result was achieved in all cases (Table 3).

Table 3. Scope of the Reaction of trans-N-alkyl Aziridine-2-carboxylates with N-alkyl/Cycloalkyl Isothiocyanatesa,b.

Isolated yields.

n.d., not detected.

As shown in Table 3, when reactions were carried out in the presence of zinc tetrafluoroborate (1 equiv) and under identical conditions, they proceeded selectively to give the unexpected thiazolidine-2-iminium salts as the sole reaction products (5c–5k) in good yields (57–81%). However, when the substituent (R1) on the aziridine skeleton was a primary carbon, the reaction proved unsuccessful (5a and 5m). The reaction also failed for 5b (R2 = benzyl group) and 5l (R1 = c-C8H15, R2 = C6H11, and Ar = p-NO2–C6H4). This clearly shows the steric effect of the substituents on the reaction outcome. On the basis of our experimental results, a plausible mechanism for the formation of compounds 4 and 5 from trans-aziridine 1 is proposed (Scheme 2), which would involve coordination of the aziridine nitrogen with the central metal cation of the Lewis acid. This induces polarization of the aziridine C–C bond, increases the electrophilicity at these two carbons, and facilitates a regio- and stereospecific nucleophilic ring opening by the sulfur atom of the isothiocyanate at the electrophilic benzylic position, with an inversion of configuration. This attack is followed by a spontaneous intramolecular cyclization with the nitrogen atom, leading to the formation of cis-iminothiazolidines 4.14,17b,17c,22 When the N-substituent of isothiocyanate was ethyl or cyclohexyl, thiazolidine-2-iminium tetrafluoroborate 5 is formed. Furthermore, despite the presence of two reactive sites (C=N) and (C=S) in the isothiocyanates, which in turn can be coordinated with a Lewis acid, it is obvious that the reaction occurs chemoselectively to provide compounds 4 or 5 as the sole products. The strong Lewis acid property of Zn(BF4)2·xH2O, which led to the formation of a complex with the resulting iminothiazolidine, may explain the amount (1 equiv) of Lewis acid used in this reaction. Purification on a chromatography column (CC) is needed to release iminothiazolidines 4. Similar stereoselective Lewis acid-mediated (3 + 2) cycloaddition reactions were suggested by Stoltz17a,23 in his works on the synthesis of cis-iminothiazolidines and thioimidates.

Scheme 2. Proposed Mechanism for the Formation of cis-Iminothiazolidines 4 and cis-Thiazolidine-2-iminium Tetrafluoroborates 5.

It is worth noting that we have already shown in a previous work19 that when the reaction is conducted in the absence of a Lewis acid, the aziridine nitrogen atom, uncoordinated in this case, attacks the electrophilic carbon of the isothiocyanate to give a zwitterion as the key intermediate. This undergoes regiospecific C–N bond cleavage to give a linear zwitterionic intermediate, which cyclizes to imidazolidine-2-thione involving the attack of the highly nucleophilic nitrogen anion onto the benzylic position.

Biological Activity

Since the 1970s until the present, many pathogens have been reported to be resistant to a wide range of antibiotics,24 especially because bacteria are known to persist in structured biofilms and rarely in cultures of single species.25 In such conditions, they can intercommunicate, exchange genetic elements, and become more resistant. Consequently, in a review sponsored by the UK Department of Health and commissioned in 2014 by the UK Prime Minister, it was reported that the number of deaths attributable to global antibiotic resistance will increase from the current 700,000 annual deaths to 10 million per year until 2050.24 Therefore, there is an urgent need to gather multiple disciplines in a one-health approach for the development of new antibiotics or new solutions that are capable of inactivating resistant microorganisms.

An ideal antibiotic is more effective if it is taken up in its target cell. However, diffusion of the antibiotic into the bacterial cytosol is limited by the membrane barriers of the bacterial cell. The negative charge of the teichoic acid residues of the cell wall of Gram-positive bacteria makes them the binding sites for positively charged molecules.26 Unlike Gram-positive bacteria, Gram-negative bacteria, due to the membrane barrier, are less susceptible to uptake anionic and neutral molecules.27

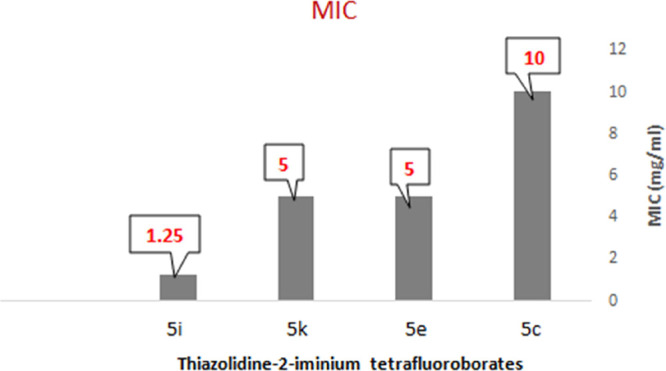

Motivated by our finding of zinc tetrafluoroborate as a Lewis acid as an effective mediator for the reaction of aziridine-2-carboxylates and isothiocyanates leading exclusively to cis-2-iminothiazolidines or cis-thiazolidine-2-iminium tetrafluoroborates, these results prompted us to study the in vitro antibacterial activities of neutral iminothiazolidines 4 and positively charged thiazolidin-2-iminium tetrafluoroborates 5 against eight Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial strains, as detailed in the experimental section. The well diffusion test was used for the preliminary biological activity evaluation of 13 iminothiazolidines 4a, 4f, 4g, and 4j and thiazolidin-2-iminium tetrafluoroborates 5c–k. Among these compounds, 5c (R1 = isopropyl), 5e (R1= cyclopentyl), 5g (R1 = cyclohexyl), and 5i (R1 = cyclooctyl) showed good inhibition against Bacillus cereus.

Note that most molecules carrying a substituent (R2 = ethyl) on the exocyclic nitrogen atom possess antibacterial activity, except for 5k where the phenyl group at position 5 is substituted by an NO2 group. Compounds 4 and 5 with a phenyl or cyclohexyl group on their endocyclic nitrogen atom are inactive and have no growth-inhibitory effects against all of the bacteria studied. On the other hand, 5c, 5e, 5g, and 5i, which have exhibited antibacterial activity, were also characterized by their minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) values, and the results showed that these compounds inhibited B. cereus at MIC values ranging from 1.25 to 10 mg/mL (Figure 2). Additionally, thiazolidin-2-iminium tetrafluoroborate 5i, substituted with a cyclooctyl group at the endocyclic N-position, has lower MICs than other thiazolidin-2-iminium tetrafluoroborate salts.

Figure 2.

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of the active thiazolidine-2-iminium tetrafluoroborate compounds against B. cereus.

Conclusions

In this study, we described the first and general method for the synthesis of new iminothiazolidines 4 and thiazolidine-2-iminium tetrafluoroborates 5 from the reaction of nonactivated aziridine-2-carboxylates with phenyl/alkyl(cycloalkyl) isothiocyanates mediated by zinc tetrafluoroborate. Our approach showed considerable efficiency compared to the previously established methods, as reactions with nonactivated trisubstituted aziridines gave very few examples for the desired iminothiazolidines. The assay to evaluate some of the synthesized compounds 4 and 5 with different substituents on both the endocyclic and exocyclic nitrogen atoms against eight Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial strains allowed us to identify four thiazolidine-2-iminium tetrafluoroborates (5c, 5e, 5g, and 5i), which were found to be the most active derivatives against B. cereus. The thiazolidine-2-iminium tetrafluoroborate system also appears to be promising for other biological activities, including antiviral potential. Further research to explore Lewis acid-mediated reactions of nonactivated aziridines with other heterocumulenes will be carried out in the future.

Experimental Section

Chemistry

General Information

All commercial products and reagents were used as purchased without further purification. Analytical thin-layer chromatography (TLC) of all reactions was performed on silica gel 60 F254 TLC plates. Visualization of the developed chromatogram was performed by UV absorbance (254 nm). Flash chromatography was carried out on silica gel 60 Å (0.063–0.2 mm). FT-IR spectra were recorded with a PerkinElmer Spectrum 1000; absorption values are given in wavenumbers (cm–1). 1H (300 MHz), 13C (75 MHz), and NMR spectra were recorded with a Bruker AV 300 spectrometer in CDCl3 as the solvent and TMS as the internal standard. 13C chemical shifts are reported in parts per million relative to the central line of the triplet at 77.16 ppm for d-chloroform. Copies of 1H and 13C NMR spectra are provided in the Supporting Information. High-resolution mass spectra were obtained using an Autoflex III system (Bruker) with electron impact (EI) ionization methods.

General Procedure for the Synthesis of cis-2-Iminothiazolidines 4(a–l) and Thiazolidin-2-iminium Tetrafluoroborate 5(c–k)

To a mixture of trans-N-alkyl aziridine-2-carboxylate 1 (1.3 mmol) and isothiocyanate (1.45 mmol) in dry DCE (7 mL) was added Zn(BF4)2·xH2O (1.3 mmol), and the mixture was stirred at reflux under nitrogen for 2–4 h. After the completion of the reaction (monitored by TLC), the reaction mixture was concentrated in a vacuum. The crude product was purified by column chromatography (silica gel, n-hexane/ethyl acetate 70/30) to give cis-2-iminothiazolidines 4 or thiazolidine-2-iminium tetrafluoroborates 5 as white solids.

cis-4-Ethoxycarbonyl-3-isopropyl-N,5-diphenylthiazolidin-2-imine (4a)

White solid (430 mg, 90% yield); mp 106–107 °C; IR (ν cm–1): 1719; 1H NMR (300 MHz CDCl3): δ 0.84 (t, 3H, J = 7.1 Hz), 1.11 (d, 3H, J = 6.8 Hz), 1.25 (d, 3H, J = 6.7 Hz), 3.56–3.85 (m, 2H), 4.46 (d, 1H, J = 7.9 Hz), 4.67 (heptet, 1H, J = 6.8 Hz), 5.05 (d, 1H, J = 7.9 Hz), 6.97–7.34 (m, 10H); 13C{1H} NMR (75 MHz CDCl3): δ 12.6, 18.7, 19.7, 46.4, 49.8, 60.1, 64.0, 121.2, 122.3, 127.5, 127.8, 132.6, 150.6, 157.0, 168.8; HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+calcd for C21H25N2O2S 369.1631; found 369.1633.

cis-4-Ethoxycarbonyl-3-isopropyl-N-phenyl-5-parachlorophenylthiazolidin-2-imine (4b)

White solid (340 mg, 65% yield); mp 127–128 °C; 1H NMR (300 MHz CDCl3): δ 0.97 (t, 3H, J = 7.2 Hz), 1.17 (d, 3H, J = 6.8 Hz), 1.31 (d, 3H, J = 6.8 Hz), 3.69–3.96 (m, 2H), 4.50 (d, 1H, J = 7.9 Hz), 4.62–4.75 (heptet, 1H, J = 6.8 Hz), 5.07 (d, 1H, J = 7.9 Hz), 7.01–7.07 (m, 3H), 7.26–7.35 (m, 7H); 13C{1H} NMR (75 MHz CDCl3): δ 13.7, 19.6, 20.7, 47.4, 50.0, 61.2, 65.0, 122.0, 123.3, 128.7, 128.9, 129.0, 132.5, 134.7, 152.1, 157.0, 169.8; HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C21H24ClN2O2S 403.1242; found 403.1246.

cis-4-Ethoxycarbonyl-3-isopropyl-N-phenyl-5-paranitrophenylthiazolidin-2-imine (4c)

White solid (386 mg, 72% yield); mp 136–137 °C; 1H NMR (300 MHz CDCl3): δ 0.97 (t, 3H, J = 7.2 Hz), 1.19 (d, 3H, J = 6.8 Hz), 1.34 (d, 3H, J = 6.8 Hz), 3.67–3.97 (m, 2H), 4.59 (d, 1H, J = 7.9 Hz), 4.63–4.73 (heptet, 1H, J = 6.8 Hz), 5.17 (d, 1H, J = 7.9 Hz), 7.01–7.09 (m, 3H), 7.28–7.33 (m, 2H), 7.60 and 8.14 (2d, 4H, J = 8.7 Hz); 13C{1H} NMR (75 MHz CDCl3): δ 13.7, 19.6, 20.7, 47.7, 49.8, 61.4, 64.7, 122.9, 123.4, 123.6, 128.9, 129.8, 141.6, 148.1, 151.9, 156.3, 169.5; HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C21H24N3O4S 414.1482; found 414.1480.

cis-4-Ethoxycarbonyl-3-n-propyl-N,5-diphenylthiazolidin-2-imine (4d)

White solid (177 mg, 37% yield); mp 86–87 °C; 1H NMR (300 MHz CDCl3): δ 0.90 (t, 3H, J = 7.2 Hz), 0.98 (t, 3H, J = 7.4 Hz), 1.63–1.75 (m, 2H), 2.98–3.07 (m, 1H), 3.68–3.99 (m, 3H), 4.56 (d, 1H, J = 8.1 Hz), 5.11 (d, 1H, J = 8.1 Hz), 7.01–7.40 (m, 10H); 13C{1H} NMR (75 MHz CDCl3): δ 11.5, 20.7, 29.7, 47.8, 49.5, 61.2, 68.7, 122.0, 123.2, 128.4, 128.5, 128.7, 128.9, 134.9, 152.1, 158.4, 168.5; HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C21H25N2O2S 369.1631; found 369.1625.

cis-4-Ethoxycarbonyl-3-cyclopropyl-N,5-diphenylthiazolidin-2-imine (4e)

White solid (290 mg, 61% yield); mp 106–107 °C; 1H NMR (300 MHz CDCl3): δ 0.57–0.73 (m, 2H), 0.90 (t, 3H, J = 7.2 Hz), 0.94–1.08 (m, 2H), 2.71 (quintet, 1H, J = 3.8 Hz), 3.71–3.97 (m, 2H); 4.44 (d, 1H, J = 7.9 Hz); 5.10 (d, 1H, J = 7.9 Hz); 7.03–7.39 (m, 10H); 13C{1H} NMR (75 MHz CDCl3):δ 5.7, 8.7, 13.7, 28.0, 49.7, 61.1, 70.2, 122.0, 123.4, 128.4, 128.5, 128.7, 128.8, 134.0, 152.2, 159.4, 168.5; HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+calcd for C21H23N2O2S 367.1475; found 367.1470.

Cis-4-Ethoxycarbonyl-3-cyclopentyl-N,5-diphenylthiazolidin-2-imine (4f)

Yield (440 mg, 86% yield); white solid; mp 109–110; 1H NMR (300 MHz CDCl3) δ 0.82 (t, 3H, J = 7.2 Hz), 1.37–2.18 (m, 2H), 3.54–3.85 (m, 2H), 4.47 (d, 1H, J = 7.9 Hz), 4.56 (m, 1H), 5.09 (d, 1H, J = 7.9 Hz), 6.96–7.34 (m, 10H); 13C{1H} NMR (75 MHz CDCl3) δ 13.6, 22.8, 23.5, 29.3, 30.0, 50.6, 57.8, 61.1, 66.5, 122.2, 123.4, 128.3,128.5, 128.7, 128.8, 133.6, 151.6, 158.7,169.5; HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C23H27N2O2S (MH)+: 395.1788; found 395.1790.

cis-4-Ethoxycarbonyl-3-cyclohexyl-N,5-diphenylthiazolidin-2-imine (4g)

White solid (445 mg, 84% yield); mp 114–115 °C; 1H NMR (300 MHz CDCl3): δ 0.82 (t, 3H, J = 7.2 Hz), 1.00–1.99 (m, 10H), 3.55–3.85 (m, 2H), 4.30 (m, 1H), 4.47 (d, 1H, J = 7.9 Hz), 5.04 (d, 1H, J = 7.9 Hz), 6.96–7.33 (m, 10H), 13C{1H} NMR (75 MHz CDCl3): δ 13.6, 25.6, 25.8, 30.4, 31.2, 51.0, 55.2, 61.0, 65.4, 122.3, 123.3, 128.5, 128.5, 128.7, 128.8, 133.5, 151.7, 158.1, 169.9; HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C24H29N2O2S 409.1944; found 409.1942.

cis-4-Ethoxycarbonyl-3-cyclohexyl-N-phenyl-5-paramethylphenylthiazolidin-2-imine (4h)

White solid (384 mg, 70% yield); mp 186–187 °C; 1H NMR (300 MHz CDCl3): δ 0.97 (t, 3H, J = 7.2 Hz), 1.19 (d, 3H, J = 6.8 Hz), 1.34 (d, 3H, J = 6.8 Hz), 3.67–3.97 (m, 2H), 4.59 (d, 1H, J = 7.9 Hz), 4.63–4.73 (quintet, 1H, J = 6.8 Hz), 5.17 (d, 1H, J = 7.9 Hz), 7.01–7.09 (m, 3H), 7.28–7.33 (m, 2H), 7.60 and 8.14 (2d, 4H, J = 8.7 Hz); 13C{1H} NMR (75 MHz CDCl3): δ 13.76, 21.8, 25.7, 25.8, 25.9, 30.4, 31.2, 50.7, 55.0, 61.0, 65.4, 122.2, 123.0, 128.4, 128.8, 129.1, 130.5, 138.5, 152.3, 157.7, 170.1; HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C25H31N2O2S 423.2101; found 423.2106.

cis-4-Ethoxycarbonyl-3-cycloheptyl-N,5-diphenylthiazolidin-2-imine (4j)

White solid (477 mg, 87% yield); mp 118–119 °C; 1H NMR (300 MHz CDCl3): δ 0.90 (t, 3H, J = 7.2 Hz), 1.41–1.77 (m, 10H), 2.00–2.08 (m, 2H), 3.63–3.91 (m, 2H), 4.44 (m,1H), 4.54 (d, 1H, J = 7.9 Hz), 5.08 (d, 1H, J = 7.9 Hz), 7.01–7.39 (m, 10H); 13C{1H} NMR (75 MHz CDCl3): δ 13.6, 24.8, 24.9, 27.6, 32.0, 33.7, 51.0, 57.4, 61.0, 65.7, 122.1, 123.0, 128.5, 128.5, 128.6, 128.8, 133.8, 152.3, 157.2, 169.9; HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C25H31N2O2S 423.2101; found 423.2103.

cis-4-Ethoxycarbonyl-3-cyclooctyl-N,5-diphenylthiazolidin-2-imine (4k)

White solid (453 mg, 80% yield); mp 120–121 °C; 1H NMR (300 MHz CDCl3): δ 0.90 (t, 3H, J = 7.2 Hz), 1.39–2.01 (m, 10H), 3.63–3.91 (m, 2H), 4.42–4.51 (m,1H), 4.55 (d, 1H, J = 7.9 Hz), 5.09 (d, 1H, J = 7.9 Hz), 7.01–7.40 (m, 10H); 13C{1H} NMR (75 MHz CDCl3): δ 13.6, 24.7, 25.1, 25.8, 26.7, 27.0, 30.5, 31.7, 51.0, 56.4, 61.0, 66.1, 122.1, 123.0, 128.5, 128.6, 128.7, 128.8, 133.9, 152.3, 157.0, 169.9; HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C26H33N2O2S 437.2257; found 437.2255.

cis-4-Ethoxycarbonyl-3-benzyl-N,5-diphenylthiazolidin-2-imine(4l)

White solid (189 mg, 35% yield); mp 75–76 °C; 1H NMR (300 MHz CDCl3): δ 0.85 (t, 3H, J = 7.2 Hz), 3.60–3.89 (m, 2H), 4.06 and 5.49 (AB, 2H, J = 14.9 Hz), 4.33 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz), 5.02 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.04–7.37 (m, 10H), 7.35 (s, 5H); 13C{1H} NMR (75 MHz CDCl3): δ 13.6, 49.3, 49.4, 61.1, 67.5, 122.0, 123.4, 127.7, 128.2, 128.4, 128.5, 128.6, 128.7, 134.8, 136.6, 151.7, 158.6, 168.1. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C25H25N2O2S 417.1631; found 417.1639.

cis-4-Ethoxycarbonyl-3-isopropyl-N-ethyl-5-phenylthiazolidin-2-iminium Tetrafluoroborate (5c)

White solid (411 mg, 78% yield); mp 162–165 °C; IR (ν cm–1): 3277, 2971, 1740, 1617, 1050, 988; 1H NMR (300 MHz CDCl3): δ 0.83 (t, 3H, J = 7.2 Hz), 1.22 (d, 3H, J = 6.6 Hz), 1.43 (d, 3H, J = 6.5 Hz),1.44 (t, 3H, J = 7.3 Hz), 3.54–3.62 (m, 2H), 3.61–3.95 (2m, 2H), 4.37 (heptet, 1H, J = 6.6 Hz), 5.03 (d, 1H, J = 8.3 Hz), 5.82 (d, 1H, J = 8.3 Hz), 7.38–7.51 (m, 5H), 13C{1H} NMR (75 MHz CDCl3): δ 13.4, 14.2, 19.4, 20.4, 44.9, 50.7, 52.1, 62.3, 67.7, 128.7, 129.1, 129.9, 167.1, 170.8. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M-BF4]+ calcd for C17H25N2O2S+ 321.1631; found 321.1632.

cis-4-Ethoxycarbonyl-3-isopropyl-N-cyclohexyl-5-phenylthiazolidin-2-iminium Tetrafluoroborate (5d)

White solid (442 mg, 74% yield); mp 215–216 °C; IR (ν cm–1): 3275, 2922, 1742, 1607, 1063, 995; 1H NMR (300 MHz CDCl3): δ 0.83 (t, 3H, J = 7.2 Hz), 1.20 (d, 3H, J = 6.6 Hz), 1.23–1.37 (m, 3H), 1.42 (d, 3H, J = 6.5 Hz), 1.67–1.85 (m, 5H), 2.06–2.10 (m, 2H), 3.26–3.36 (m, 1H), 3.59–3.94 (2m, 2H), 4.42 (heptet, 1H, J = 6.6 Hz), 5.06 (d, 1H, J = 8.3 Hz), 5.84 (d, 1H, J = 8.3 Hz), 7.37–7.54 (m, 5H), 8.12 (d, 1H, J = 8 Hz); 13C{1H} NMR (75 MHz CDCl3): δ 13.4, 19.4, 20.3, 24.5, 25.1, 31.8, 32.1, 50.5, 51.9, 61.6, 62.3, 67.5, 128.7, 129.0, 129.6, 129.8, 167.2, 169.6. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M-BF4]+ calcd for C21H31N2O2S+ 375.2100; found 462.2102.

cis-4-Ethoxycarbonyl-3-cyclopentyl-N-ethyl-5-phenylthiazolidin-2-iminium Tetrafluoroborate (5e)

White solid (450 mg, 80% yield); mp 142–145 °C; IR (ν cm–1): 3275, 2959, 1740, 1617, 1049, 991; 1H NMR (300 MHz CDCl3): δ 0.82 (t, 3H, J = 7.2 Hz), 1.44 (t, 3H, J = 7.2 Hz), 1.51–2.30 (m, 8H), 3.54–3.68 (m, 3H), 3.84–3.95 (m, 1H), 4.29 (quint, 1H, J = 6.6 Hz), 5.04 (d, 1H, J = 8.4 Hz), 5.82 (d, 1H, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.39–7.51 (m, 5H), 8.35 (br, 1H, NH); 13C{1H} NMR (75 MHz CDCl3): δ 13.4, 14.2, 22.6, 23.1, 29.3, 30.0, 44.9,51.9, 59.3, 62.4, 69.0, 128.7, 129.1, 129.7, 129.9, 167.0, 171.0. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M-BF4]+ calcd for C19H27N2O2S+ 347.1787; found 347.1788.

cis-4-Ethoxycarbonyl-3-cyclopentyl-N-cyclohexyl-5-phenylthiazolidin-2-iminium Tetrafluoroborate (5f)

White solid (515 mg, 81% yield); mp 192–193 °C; IR (ν cm–1): 3258, 2939, 1743, 1611, 1064, 992; 1H NMR (300 MHz CDCl3): δ 0.82 (t, 3H, J = 7.2 Hz), 1.19–2.33 (m, 18H), 3.22–3.38 (m, 1H), 4.58–3.94 (2m, 2H), 4.29–4.42 (m, 1H), 5.02 (d, 1H, J = 8.4 Hz), 5.80 (d, 1H, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.38–7.51 (m, 5H), 8.12 (d, 1H, J = 8.2 Hz); 13C{1H} NMR (75 MHz CDCl3): δ 13.4, 22.5, 23.1, 24.5, 25.1, 29.2, 30.0, 31.8, 32.1, 51.8, 59.1, 61.7, 62.3, 68.8, 128.6, 129.1, 129.7, 129.9, 167.0, 170.0. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M-BF4]+ calcd for C23H33N2O2S+ 401.2257; found 401.2259.

cis-4-Ethoxycarbonyl-3-cyclohexyl-N-ethyl-5-phenylthiazolidin-2-iminium Tetrafluoroborate (5g)

White solid (463 mg, 80% yield); mp 171–173 °C; IR (ν cm–1): 3274, 2928, 1741, 1617, 1055, 992; 1H NMR (300 MHz CDCl3): δ 0.83 (t, 3H, J = 7.2 Hz), 1.02–1.21 (m,2H), 1.44 (t, 3H, J = 7.2 Hz), 1.50–1.98 (m, 8H), 3.51–3.70 (m, 3H), 3.84–4.06 (m, 2H), 5.00 (d, 1H, J = 8.4 Hz), 5.76 (d, 1H, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.38–7.50 (m, 5H), 8.43 (m, 1H); 13C{1H} NMR (75 MHz CDCl3): δ 13.3, 14.2, 24.6, 24.8, 24.9, 30.0, 30.8, 44.8, 52.1, 58.0, 62.3, 68.0, 128.6, 129.1, 129.5, 129.9, 167.1, 171.0. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M-BF4]+ calcd for C20H29N2O2S+ 361.1944; found 361.1945.

cis-4-Ethoxycarbonyl-3-cyclohexyl-N-ethyl-5-paranitrophenylthiazolidin-2-iminium Tetrafluoroborate (5h)

White solid (526 mg, 82% yield); mp 175–176 °C; IR (ν cm–1): 3268, 2934, 1742, 1621, 1051, 995; 1H NMR (300 MHz CDCl3): δ 0.89 (t, 3H, J = 7.1 Hz), 1.05–1.25 (m, 2H), 1.46 (t, 3H, J = 7.3 Hz), 1.53–2.11 (m, 8H), 3.58–3.75 (m, 3H), 3.91–4.03 (m, 2H), 5.21 (d, 1H, J = 8.4 Hz), 6.02 (d, 1H, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.79 et 8.25 (2d, 5H, J = 8.8 Hz), 8.44 (brs, 1H); 13C{1H} NMR (75 MHz CDCl3): δ 13.5, 14.2, 24.7, 24.8, 29.9, 30.6, 45.0, 50.9, 58.3, 62.6, 67.8, 124.0, 130.1, 137.2, 148.6, 167.0, 170.1. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M-BF4]+ calcd for C20H28N3O4S+ 406.1795; found 406.1797

cis-4-Ethoxycarbonyl-3-cyclooctyl-N-ethyl-5-phenylthiazolidin-2-iminium Tetrafluoroborate (5i)

White solid (444 mg, 72% yield); mp 156–157; IR (ν cm–1): 3268, 2927, 1744, 1617, 1053, 992; 1H NMR (300 MHz CDCl3): δ 0.84 (t, 3H, J = 7.1 Hz), 1.44 (t, 3H, J = 7.2 Hz), 1.52–2.01 (m, 14H), 3.54–3.70 (m, 3H), 3.85–3.96 (m, 1H), 4.05–4.20 (m, 1H), 5.00 (d, 1H, J = 8.2 Hz), 5.76 (d, 1H, J = 8.1 Hz), 7.38–7.51 (m, 5H), 8.40 (brs, 1H); 13C{1H} NMR (75 MHz CDCl3) δ 13.4, 14.2, 23.3, 24.3, 24.8, 26.3, 27.1, 29.7, 30.4, 44.9, 52.4, 60.3, 62.3,69.1, 128.6, 129.1, 129.5, 167.0, 170.4. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M-BF4]+ calcd for C22H33N2O2S+ 389.2257; found 389.2261.

cis-4-Ethoxycarbonyl-3-cyclooctyl-N-cyclohexyl-5-phenylthiazolidin-2-iminium Tetrafluoroborate (5j)

White solid (454 mg, 66% yield); mp 186–187 °C; IR (ν cm–1): 3251, 2930, 1741, 1608, 1065, 976; 1H NMR (300 MHz CDCl3): δ 0.85 (t, 3H, J = 7.1 Hz), 1.26–2.08 (m, 24H), 3.22–3.40 (m, 1H), 3.61–3.97 (2m, 2H), 4.20–4.34 (m, 1H), 4.93 (d, 1H, J = 8.1 Hz), 5.65 (d, 1H, J = 8.1 Hz), 7.39–7.48 (m, 5H), 8.33 (d, 1H, J = 8.2 Hz); 13C{1H} NMR (75 MHz CDCl3): δ 13.4, 23.1, 24.0, 24.4, 24.6, 25.2, 26.5, 27.5, 29.4, 30.4, 31.7, 32.0, 52.5, 59.9, 62.0,62.4, 68.8, 128.5, 129.2, 129.4, 130.0, 167.0, 169.1. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M-BF4]+ calcd for C26H39N2O2S+ 443.2726; found 443.2732.

cis-4-Ethoxycarbonyl-3-cyclooctyl-N-ethyl-5-paranitrophenylthiazolidin-2-iminium Tetrafluoroborate (5k)

White solid (377 mg, 57% yield); mp 158–160 °C; IR (ν cm–1): 3259, 2912, 1741, 1619, 1008; 1H NMR (300 MHz CDCl3): δ 0.90 (t, 3H, J = 7.1 Hz), 1.46 (t, 3H, J = 7.2 Hz), 1.49–2.07 (m, 14H), 3.59–4.02 (2m, 4H), 4.05–4.18 (m, 1H), 5.17 (d, 1H, J = 8.2 Hz), 6.00 (d, 1H, J = 8.1 Hz), 7.79 et 7.24 (2d, 4H, J = 8.8 Hz), 8.39 (brs, 1H); 13C{1H} NMR (75 MHz CDCl3): δ 13.6, 14.3, 23.2, 24.4, 24.7, 26.3, 27.0, 29.6, 30.2, 45.1, 51.1, 60.6, 62.5, 68.8, 124.0, 130.2, 137.3, 148.6, 166.6, 169.9. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M-BF4]+ calcd for C22H32N3O2S+ 434.2108; found 434.2113.

Antibacterial Activity Assay

The in vitro antibacterial activities of the synthesized molecules were evaluated with respect to eight microbial strains: four Gram-positive bacteria (Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212, Enterococcus faecium ATCC 19436, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 6538, and Bacillus cereus 49) and four Gram-negative bacteria (Escherichia coliDH5α, Escherichia coli ATCC 8739, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Salmonella sp). These strains belong to the collection of the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and the Laboratory of Microorganisms and Active Biomolecules (LMBA-LR03ES03), University of Tunis El Manar. As a first screening, the antibacterial activities of all molecules (suspended in DMSO solution, 30%) were evaluated by the well diffusion method toward all the bacterial strains. The active molecules were evaluated by a second test for determining their minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs). These tests were performed as described below. In all tests, the synthesized molecules were suspended in DMSO (30%), which was used as the negative control, and gentamicin was used as the reference antibacterial drug.

Well Diffusion Method

Suspensions (5 mL) of molten soft agar (0.75% w/v), inoculated with fresh cultures of the tested strains at a final concentration of 106 CFU/mL, were poured onto the surfaces of tryptone soy agar (TSA) plates. After cooling, wells of 5 mm diameter were created, and their bases were sealed with soft agar. The wells were then filled with solutions of the synthesized molecules. After 24 h of incubation at 30 °C, samples showing growth inhibition halos around the wells were considered as active.

Minimum Inhibitory Concentration Determination

The MICs of the active compounds were determined using the microdilution broth method, as recommended by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS). Stock solutions of the tested compounds in DMSO were serially diluted to final concentrations ranging from 104 to 78.125 μg/mL in sterile 96-well microtiter plates containing Mueller–Hinton broth (MHB). Fresh culture of the bacterial strain was used at a volume of 100 μL for each well, after turbidity adjustment to 0.5 McFarland. Growth indicator (G-stain) (100 μL of 0.1%) was incorporated into each well to assess the bacterial inhibition. The wells containing inoculums alone were used as negative controls, and gentamycin was used as a positive control. All samples were tested in duplicate, and microplates were incubated at 30 °C for 24 h.

MICs were determined by at least 90% reduction in growth (IC90) compared to the control using a Biolog assay (BiologOmnilog Phenotype MicroArray) incubator, which is connected to a programmable computer allowing the tracking of the growth cycle of microorganisms, and displays the result as a growth curve.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Tunisian Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research for the financial support of this research (LR99ES15) and to Dr. M.A. Sanhoury, MRSC of the Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Sciences of Tunis, for helpful discussion.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.3c03531.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- D’hooghe M.; De Kimpe N. Synthetic approaches towards 2-iminothiazolidines: an overview. Tetrahedron 2006, 62, 513–535. 10.1016/j.tet.2005.09.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Takagi M.; Ishimitsu K.; Nishibe T.. Oxa(thia)zolidine derivative and anti-inflammatory drug. US 6762200 B2, 2004, 10.1093/nass/48.1.297. [DOI]

- Bhalgat C. M.; Darda P. V.; Bothara K. G.; Bhandari S. V.; Gandhi J.; Ramesh B. Synthesis and pharmacological screening of some novelanti-hypertensive agents possessing 5-Benzylidene-2-(phenylimino)-thiazolidin-4-onering. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 76, 580–588. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zubova O. V.; Fedoseev V.; Silaev A. B. Study ofthe antitumoractivity of some derivatives of 2,3-di(isothiuronium)-propanoland 2-imino-5-(isothiuronium)-methyl-thiazolidine. Vopr. Onkol. 1964, 10, 26–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla U. K.; Singh R.; Khanna J. M.; Saxena A. K.; Singh H. K.; Sur R. N.; Dhawan B. N.; Anand N. Synthesis of trans-2-[N-(2-Hydroxy-1,2,3,4-tetrahydronaphthalene-1-yl)]imino-thiazolidineand Related Compounds - A New Class of Antidepressants. Collect. Czech. Chem. Commun. 1992, 57, 415–424. 10.1135/cccc19920415. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon B. R.; Bagi C. M.; Brennan C. R.; Brittelli D. R.; Bullock W. H.; Chen J.; Collibee W.; Dally R.; Johnson J. S.; Kluender H. C. E.. Substituted2-arylimino heterocycles and compositions containing them, for useas progesterone receptor binding agents. US 6353 006, Mars 5, 2002, 10.1080/13651820260503837. [DOI]

- Ueda S.; Terauchi H.; Yano A.; Matsumoto M.; Kubo T.; Kyoya Y.; Suzuki K.; Ido M.; Kawasaki M. 4,5-Dialkylsubstituted 2-imino-1,3-thiazolidine derivatives as potent inducible nitric oxide synthase inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2004, 12, 4101–4116. 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosseinimehr S. J.; Shafiee A.; Mozdarani H.; Akhlagpour S.; Froughizadeh M. Radioprotective Effects of 2-Imino-3-[(chromone-2-yl)carbonyl]thiazolidinesagainst γ-Irradiation in Mice. J. Radiat. Res. 2002, 43, 293–300. 10.1269/jrr.43.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Elbert A.; Buchholz A.; Ebbinghaus-Kintscher U.; Nauen R.; Erdelen C.; Schnorbach H. J. The biological profile of thiacloprid- a new chloronicotinyl insecticide. Pflanzensuchtz-Nachri. Bayer 2001, 54, 185–208. [Google Scholar]; b Schulz-jander D. A.; Leimkuehler W. M.; Casida J. E. Neonicotinoid Insecticides: Reduction and Cleavage of Imidacloprid Nitroimine Substituent by Liver Microsomaland Cytosolic Enzymes. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2002, 15, 1158–1165. 10.1021/tx0200360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birman V. B.; Li X. Benzotetramisole: ARemarkably Enantioselective Acyl Transfer Catalyst. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 1351–1354. 10.1021/ol060065s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’hooghe M.; Waterinckx A.; De Kimpe N. A Novel Entry toward 2-Imino-1,3-thiazolidinesand 2-Imino-1,3-thiazolines by Ring Transformation of 2-(Thiocyanomethyl)aziridines. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 70, 227–232. 10.1021/jo048486f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H.-B.; Dong C.; Alper H. Novel Rhodium-Catalyzed Reactionof Thiazolidine Derivatives with Carbodiimides. Chem.—Eur. J. 2004, 10, 6058–6065. 10.1002/chem.200400543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coin G.; De Ferrier De Montal O.; Dubourdeaux P.; Latou J.-M. Expedient Synthesisof 2-Iminothiazolidines via Telescoping Reactions Including Iron-CatalyzedNitrene Transfer and Domino Ring-Opening Cyclization (DROC). Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 3, 443–448. 10.1002/ejoc.202001379. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Satheesh V.; Kumar S. V.; Vijay M.; Barik D.; Punniyamurthy T. Metal-Free [3 + 2]-Cycloadditionof Thiiranes with Isothiocyanates, Isoselenocyanates and Carbodiimides: Synthesis of 2-Imino-Dithiolane/Thiaselenolane/Thiazolidines. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2018, 7, 1583–1586. 10.1002/ajoc.201800274. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira M.; Sa M. M. Formal [3 + 2] Annulation Involving Allylic Bromides and Thioureas. Synthesis of 2-Iminothiazolidines through a Base-Catalyzed Intramolecular anti-Michael Addition. Adv. Synth.Catal. 2015, 357, 829–833. 10.1002/adsc.201401026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Minakata S.; Hotta T.; Oderaotoshi Y.; Komatsu M. Ring Opening and Expansionof Aziridines in a Silica-Water Reaction Medium. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 7471–7472. 10.1021/jo061239m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Craig R. A.; O’Connor N. R.; Goldberg A. F. G.; Stoltz B. M. StereoselectiveLewis Acid Mediated (3 + 2) Cycloadditions of N-H-and N-Sulfonylaziridines with Heterocumulenes. Chem.—Eur. J. 2014, 20, 4806–4813. 10.1002/chem.201303699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Bhattacharyya A.; Kavitha C. V.; Ghorai M. K. Stereospecific Synthesis of 2-Iminothiazolidinesvia Domino Ring-Opening Cyclization of Activated Aziridines with Aryl-and Alkyl Isothiocyanates. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 6433–6443. 10.1021/acs.joc.6b01551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Gao L.; Fu K.; Fheng G. Quickly FeCl3-catalyzed highly chemo- and stereo-selective [3 + 2] dipolar cycloadditionof aziridines with isothiocyanates. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 47192–47195. 10.1039/C6RA04923K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Sengoden M.; Irie R.; Punniyamurthy T. EnantiospecificAluminum-Catalyzed (3 + 2) Cycloaddition of Unactivated Aziridines with Isothiocyanates. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 11508–11513. 10.1021/acs.joc.6b02190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Sengoden M.; Vijay M.; Balakumar E.; Punniyamurthy T. Efficient pyrrolidine catalyzed cycloaddition of aziridines with isothiocyanates, isoselenocyanates and carbon disulfide “onwater”. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 54149–54157. 10.1039/C4RA08902B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; f Wu J.-Y.; Luo Z.-B.; Dai L.-X.; Hou X.-L. Tributylphosphine-CatalyzedCycloaddition of Aziridines with Carbon Disulfide and Isothiocyanate. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 9137–9139. 10.1021/jo801703h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Baeg J.-O.; Alper H. Novel Palladium(II)-Catalyzed Cyclization of Aziridines and SulfurDiimides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994, 116, 1220–1224. 10.1021/ja00083a007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; h Goldberg A. F. G.; O’Connor N. R.; Craig R. A.; Stoltz B. M. Lewis Acid Mediated (3 + 2) Cycloadditionsof Donor-Acceptor Cyclopropanes with Heterocumulenes. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 5314–5317. 10.1021/ol302494n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengoden M.; Punniyamurthy T. “On Water”: Efficient Iron-Catalyzed Cycloaddition of Aziridines with Heterocumulenes. Angw. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 572–575. 10.1002/anie.201207746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabarki M. A.; Besbes R. Selective synthesis of imidazolidine-2-thiones viaring expansion of aziridine-2-carboxylates with isothiocyanates. Tetrahedron Lett. 2016, 57, 3832–3836. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2016.07.040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pujala B.; Rana S.; Chakraborti A. K. Zink tetrafluoroboratehydrate as a mild catalyst for epoxide ring opening with amines: scopeand limitations of metal tetrafluoroborates and applications in the synthesis of antihypertensive drugs (RS)/(R)/(S)-metoprolols. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 76, 8768–8780. 10.1021/jo201473f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar A.; Santra S.; Kundu S.K.; Ghosal N.C.; Hajra A.; Majee A.. Zinc tetrafluoroborate: A versatile and robust catalyst for various organic reactions and transformations. Synthesis 2015, 471379–1386. 10.1055/s-0034-1380168 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dahiya A.; Ali W.; Patel B. K. Catalystand solvent free domino ring opening cyclization: A greener and atomeconomic route to 2-iminothiazolidines. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 4272–4281. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.7b04723. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg A. F. G.; O’Connor N. R.; Craig R. A.; Stoltz B. M. Lewis acid mediated (3 + 2) cycloaddition of donor-acceptor cyclopropanes with heterocumulenes. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 5314–5317. 10.1021/ol302494n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laxminarayan R.; Matsoso P.; Pant S.; Brower C.; Røttingen J.-A.; Klugman K.; Davies S. Access to effective antimicrobials: a worldwide challenge. Lancet 2016, 387, 168–175. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00474-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davey M.-E.; O’Toole G.-A. Microbial Biofilms: from Ecology to Molecular Genetics. Microbiol Mol. Biol. Rev. 2000, 64, 847–867. 10.1128/MMBR.64.4.847-867.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert P. A. Cellular impermeability and uptakeof biocides and antibiotics in gram-positive bacteria and mycobacteria. Soc. Appl. Microbiol. Symp. Ser. 2002, 31, 46S–54S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock R. E. Alterationsin outer membrane permeability. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 1984, 38, 237–264. 10.1146/annurev.mi.38.100184.001321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.