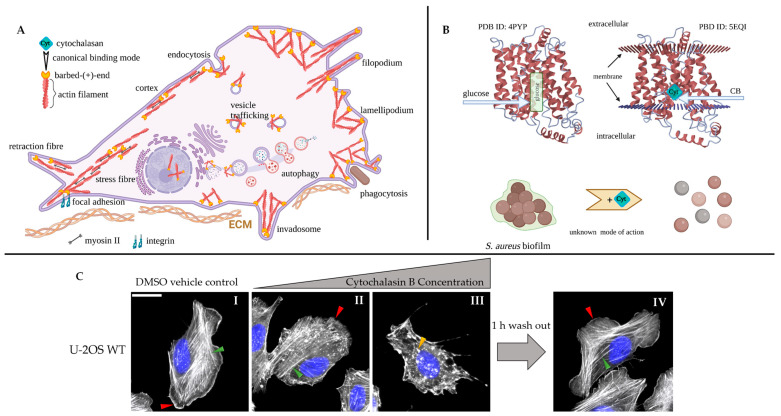

Figure 1.

(A). Schematized overview of selected, intracellular actin filament structures and the cellular processes these structures contribute to (filaments and molecules not drawn to scale). The respective positions of filament barbed ends, which cytochalasans are assumed to bind to, are also indicated. Although all actin filament barbed ends are potential targets of cytochalasans, in principle, differential effects on different actin structures can be observed, but the precise molecular reasons for this have yet to be established (for details, see text). (B) Selected, actin-independent activities of cytochalasans. (C). Representative epifluorescence images of human osteosarcoma cells stained for nuclear DNA using DAPI (pseudocolored in blue) and actin filaments with fluorescently-coupled phalloidin (in grey), treated with vehicle control (DMSO, I) or low and high concentrations of CB (1, II + III) for 1 h, with the latter followed by 1 h washout, as indicated (IV). Control U-2 OS cells display discernible stress fibers (I, green arrowhead) and F-actin-rich lamellipodia (I, red arrowhead). Low-dose CB (1) treatments remove lamellipodia at the cell periphery (II, red arrowhead) and cause partial induction of F-actin-rich spots, the precise nature of which is elusive, with stress fibers remaining largely intact (II, green arrowhead). The latter disappear upon high-dose CB (1); aggregates grow even larger (III, orange arrowhead). In spite of these drastic phenotypic changes, a washout for 1 h is sufficient for full recovery of the U-2 OS cell actin network (IV, red arrowhead: lamellipodium, green arrowhead: stress fiber). Figure subpanels (A,B) were created with BioRender.com.