Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this case report was to describe the multimodal care of a patient with the sudden onset of truncal tremors.

Clinical Features

A 30-year-old female patient presented for chiropractic care with truncal tremors following a motor vehicle accident. Initial outcome measures included the Neck Disability Index (50%) and Oswestry Disability Index (62). The patient's truncal tremors became worse during spinal cord compression testing that included passive cervical flexion and slouched posture. The Romberg test was positive for swaying. Assessments of active range of motions of the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine were moderately reduced in all ranges. Case history, physical examinations, diagnostic imaging, and neurology consultations led to a diagnosis of functional truncal tremors. The patient was being concurrently managed by other health care providers. Magnetic resonance imaging studies were ordered by a neurologist and primary medical physician, which showed no structural abnormalities in brain neuroanatomy or spine.

Intervention and Outcome

The multimodal chiropractic care included whole-body vibration therapy (WBVT), spinal manipulative therapy (SMT), and acupuncture therapy. The treatment plan included 8 weekly appointments in which the patient received WBVT and SMT. During treatment weeks 2 to 6, the patient received acupuncture therapy, which occurred immediately following their treatment appointment for WBVT and SMT. The patient practiced stress reduction techniques, as advised by the neurologist, eliminated caffeine, and performed daily yoga exercises for 30 minutes. The Romberg test was negative after the third treatment. The patient was discharged after chiropractic visit 12, 95 days post-accident, as she reached maximal medical improvement. Truncal tremors were still present, but the patient described them as “barely noticeable.”

Conclusion

The patient reported improvement under a course of chiropractic care using a multimodal approach, including behavioral, pharmacological, and manual therapies. This case study suggests that WBVT, SMT, and acupuncture therapy may assist some patients with functional movement disorders.

Key Indexing Terms: Tremor, Chiropractic, Vibration, Psychosocial Intervention, Acupuncture Therapy

Introduction

Functional movement disorders are seen by neurologists in association with stressful psychological and physical events.1, 2, 3, 4 Although causes of functional movement disorders (FMDs) are not fully understood, the current hypothesis describes changes in neurophysiological responses within the central nervous system, as opposed to neurodegeneration of structures of the central nervous system.1, 2, 3,5, 6, 7 Decreased inhibitory responses from the basal ganglia-thalamo-cortical and cerebello-thalamo-cortical pathways and increased activation of limbic pathways may contribute to FMDs.1, 2, 3, 4,8, 9, 10

There are numerous studies describing the clinical characteristics of FMD; however, diagnosing FMD remains challenging.1,3,7,11,12 Although there is no consensus on the optimal treatment strategy for FMD, there is increasing evidence suggesting treatments for FMD provide a multimodal approach, including behavioral, pharmacological, and manual therapies.1, 2, 3 An effectively communicated and timely diagnosis and an appropriate multimodal treatment approach are critical because clinical outcomes for FMDs are typically poor,1, 2, 3,5,7 and symptoms contribute to biopsychosocial disabilities.1,4,5,11

Reporting of adult-onset movement disorders involving the trunk is limited to a small number of case studies of truncal dystonia.13, 14, 15, 16 Only 1 case study described a multimodal treatment approach for truncal dystonia, while other case studies described pharmacological approaches or deep brain stimulation to treat adult-onset truncal dystonia.13, 14, 15, 16 The multimodal treatment approach was a 2-year physical therapy program that included rehabilitation exercises, abdominal kinesio taping, gait and balance training, and sensory “tricks.”16 At the 12-month follow-up assessment, noteworthy clinical outcomes were decreases in pain, better control of the dystonic muscles, improvements in physical function, and decreases in doses of botulinum toxin.16

Truncal movement disorders are rare, with only 5% of clinical tremor syndromes involving the trunk musculature.8,11 Although the etiology of adult-onset truncal dystonia is idiopathic,15 head trauma or whiplash injuries may contribute to adult-onset truncal movement disorders.17, 18, 19, 20 Total body tremors that include bobbing of the head and trunk are frequently observed in patients diagnosed with an FMD.3

The authors were not able to identify any current literature on chiropractic multimodal treatment for truncal tremors. Therefore, this case report describes the multimodal care of a patient with sudden onset of truncal tremors following a motor vehicle accident (MVA).

Case Report

A 30-year-old female patient was involved in an MVA, which involved the patient's car being rear-ended by another car at 40 mph while the patient's car was stopped at a traffic light. The patient self-admitted herself to the emergency room (ER) the following day (Day 1) for chief complaints of full-body tremors, neck pain, and a right-sided headache. Medical management in the ER following the MVA (Day 0) included a neck brace, 800 mg of ibuprofen and 10 mg of cyclobenzaprine HCl. The full body tremors included bobbing of the head and trunk. Imaging findings of a brain computed tomography scan without contrast were unremarkable. There were no changes to the medical management plan.

Four days post-MVA, she sought chiropractic care. She presented for chiropractic care with symptoms of neck and low back pain and truncal tremors. During the history, the patient expressed frustration that she did not feel that providers at the ER considered her truncal tremors. She had no prior history of medical conditions, musculoskeletal, or psychological disorders.

She was seeing multiple health care providers who worked separately with the patient—a chiropractor, an acupuncturist, medical physicians, and a psychologist. The patient was managed in a silo approach in which the various health care providers did not communicate case details. Each treatment visit was independent of the other treatment visits, such that the practitioners were not working together on the case. For a timeline of the case, see the supplementary data.

Physical Exam

Chiropractic examination included muscle testing that revealed C5 to T1, L1 to L3, and S1 muscle strengths that were 5/5, while L4 and L5 muscle strengths were 4/5. Deep tendon reflex and sensory testing of upper and lower extremities were normal. Pathological reflexes were absent. The Babinski Weil test and a tandem gait assessment revealed gait deviations to the right. Orthopedic tests for nerve root compression were negative. Active range of motions of the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine was moderately reduced in all ranges. The Neck Disability Index was 50%. The Oswestry Disability Index was 62. Based on these findings, the chiropractor referred the patient to a medical primary care physician (PCP).

Treatment and Further Evaluation

Eleven days post-MVA, the PCP prescribed 2 mg of valium for anxiety and cleared the patient for chiropractic treatment. After the PCP appointment, the patient returned to the chiropractic clinic. At chiropractic visit 2, manual soft tissue manipulation techniques were applied along the spine, with the treatment goal to reduce pain, relax muscles, increase range of motion, and reduce inflammation.21 High-velocity, low-amplitude (HVLA) chiropractic spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) to the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spinal segments was performed. However, there were no visible changes to truncal tremors.

The patient returned to the orthopedic physician 18 days post-MVA and was prescribed 500 mg of naproxen for pain management and provided a referral to a neurologist. Nineteen days post-MVA, the patient returned to the chiropractic clinic for visit 3. The patient reported that she discontinued the use of the prescribed valium as she did not perceive any benefit. The neurological and orthopedic physical examination findings were mostly the same as recorded at the initial chiropractic consultation. However, new neurological findings included increased sensation over the left L5 dermatome and loss of vibratory sense on the left leg. These new neurological findings and the ongoing gait deviations to the right during the tandem gait assessment and the Babinski-Weil test were deemed yellow flags for performing SMT. Spinal manipulative therapy was not performed at visit 3. A clinical decision was made to wait until after the appointment with the neurologist before resuming SMT.

Introduction of Whole-Body Vibration Therapy

The neurologist diagnosed the patient with psychogenic (functional) truncal tremors 29 days post-MVA. The neurologist provided the patient with advice on stress reduction that included a self-help book and gave the patient a referral to a psychologist. At chiropractic visit 4, 32 days post-MVA, the patient expressed anger at the neurologist's “psychological diagnosis.” The patient reported that she was no longer experiencing neck and low back pain, but truncal tremors were persistent and interfering with her activities of daily living. In the absence of back pain, a clinical decision was made to wait for a second opinion from a chiropractic neurologist before resuming SMT. Although the chiropractor decided against using SMT at this visit, the modality of whole-body vibration therapy (WBVT) was introduced. The patient stood on the PowerPlate with settings for WBVT at 25 Hz and low amplitude for a duration of 30 seconds (Pro5 Model; PHS LLC, London, United Kingdom). Whole-body vibration therapy was repeated 3 times with 1 minute between repetitions. Decreases in frequency and amplitude of the truncal tremors were visually observed immediately after WBVT.

The patient scheduled an appointment for a neurological evaluation by a chiropractor who was a Diplomate of the International Board of Chiropractic Neurology that occurred 38 days post-MVA. Cranial nerve evaluation of the eyes with light stimulation resulted in nausea. The Romberg test was positive for swaying, and the patient demonstrated extreme movements in an attempt to maintain balance during the test. Patient's truncal tremors became worse during spinal cord compression testing, which included passive cervical flexion and slouched posture. At 47 days post-MVA, a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study of the cervical spine was ordered, which ruled out spinal cord compression.

Implementation of Treatment Plan

After the patient learned of these MRI diagnostic findings, she returned to the chiropractic clinic for visit 5 on the same day, 47 days post-MVA. The treating chiropractor confirmed the FMD diagnosis by the medical neurologist based upon the second opinion from the chiropractic neurologist and the report of findings from the MRI study of the cervical spine. However, the communication of the FMD diagnosis included the following: (1) a description of changes in neurophysiologic responses that may contribute to FMD1, 2, 3,5,7; and (2) an explanation that head trauma or whiplash injuries may contribute to the adult-onset of truncal movement disorders.17, 18, 19, 20 Over the next 8 weeks, the patient was treated with chiropractic care once a week, that is, chiropractic visits 5 to 12. At each visit, the patient received SMT (same as chiropractic visit 2), followed by WBVT (same as chiropractic visit 4). The clinical outcome was the Romberg test that the patient performed before treatment, after SMT, and after each repetition of WBVT. The Romberg test was the primary clinical outcome because an exaggerated Romberg response is a general characteristic of FMD.1

Introduction of Acupuncture Therapy

After completing SMT and WBVT at chiropractic visits 6 to 10, the patient received acupuncture therapy. The acupuncture therapy included tuina massage of the back musculature, moxibustion treatment using a moxa pole that was held over the skin to warm the acupuncture points, and the insertion of 17 acupuncture needles, as determined by the traditional Chinese medicine diagnostic pattern. The patient reported slower, more rhythmic truncal tremors at the completion of each acupuncture treatment.

During the 8 weeks of the multimodal treatment approach, the patient practiced stress reduction techniques, eliminated caffeine, and performed daily yoga for 30 minutes. The patient also followed up with the psychologist referral.

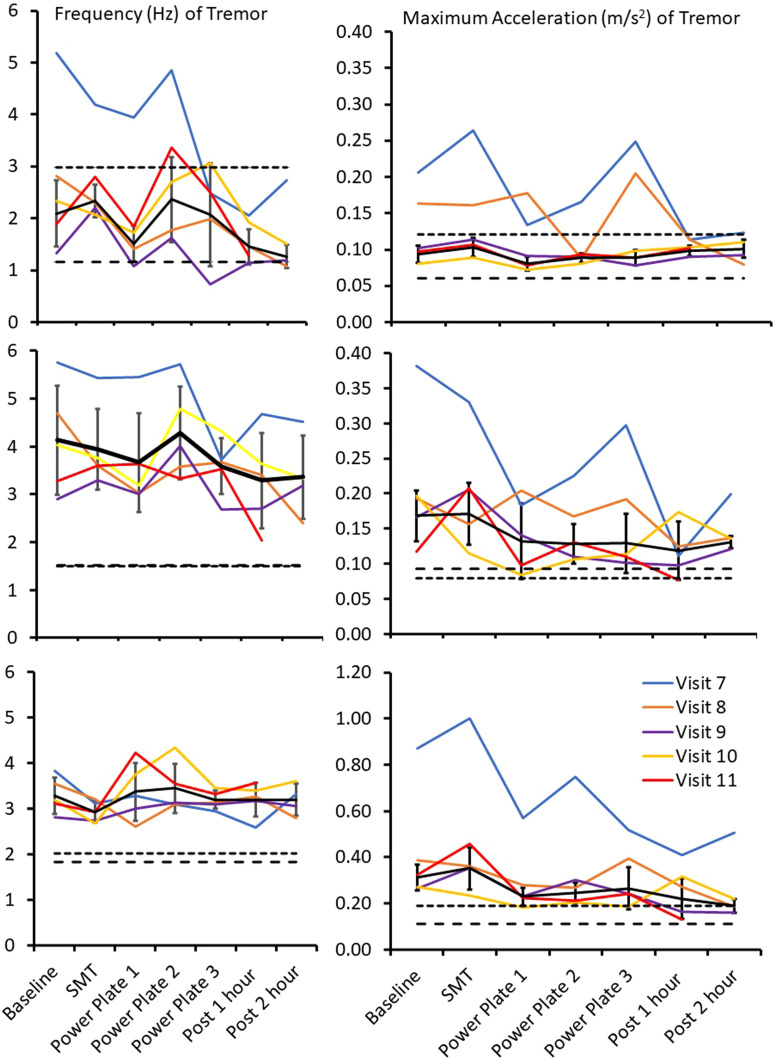

After the chiropractor visually observed decreases in tremor amplitude and frequency following the repetitions of WBVT, measurements of truncal tremors by accelerometry were included as part of the clinical outcomes. An iPhone 6 (Apple, Cupertino, California) was strapped onto the patient's trunk anteriorly at the T12 segmental level to quantify truncal tremors at chiropractic visit 7. Maximum acceleration and average tremor frequency were quantified from 30 seconds of data collection using the accelerometer phone application Physics Toolbox (Apple Online Store, Apple.com) while the patient was standing. The measurements were recorded before treatment, after SMT, after each repetition of WBVT, as well as 1 and 2 hours after the chiropractic visit.

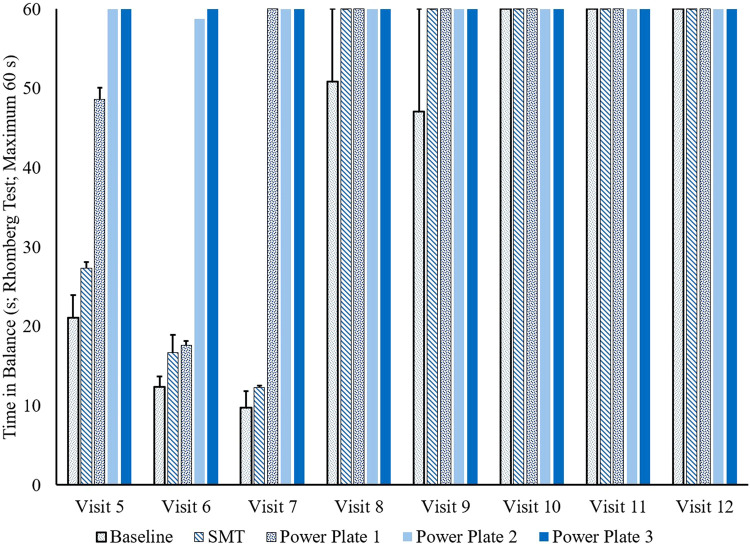

Romberg tests were positive at chiropractic visits 5 to 7 and negative at chiropractic visits 8 to 12 (Fig 1). Following WBVT at chiropractic visits 5 to 7, the patient was able to maintain balance for 60 seconds. There were visually observed decreases in tremor amplitude and frequency that occurred immediately following the multimodal treatment approach at visits 5 to 9. These visually observed decreases in tremor amplitude and frequency persisted for 2 hours after treatment visits 5 to 9. Measurements of the frequency and acceleration of the truncal tremors by accelerometry were inconclusive within and across treatment sessions (Fig 2). It is important to note that the amplitude of tremors is the most bothersome symptom for patients.22 The accelerometry data acquisition did not quantify the amplitude of truncal tremors. However, the accelerometry data detected that the truncal tremor frequency was greater than control values and fewer than 4 to 6 Hz within and across treatment sessions (Fig 1). Tremor frequencies greater than 4 to 6 Hz suggest that tremors are volitional or exaggerated physiologic tremors.6,7,22 Maximum accelerations of truncal tremors approached control values within and across treatment visits (Fig 2).

Fig 1.

Romberg test: changes in time in balance during the treatment phase (chiropractic visits 5-12). The patient performed the Romberg test 3 times before treatment (baseline), after SMT, and after each of the PowerPlate repetitions. At baseline for chiropractic visits 8 and 9, 2 of the 3 administrations of the Romberg test were negative, that is, a maximum of 60 seconds in balance. The remaining administrations of the Romberg test were negative during chiropractic visits 8 to 12. Error bars are standard deviations. SMT, spinal manipulative therapy.

Fig 2.

Frequency of truncal tremors (left panels) and maximum acceleration (right panels) in 3-dimensional motion planes (top panels: anterior-posterior; middle panels: medial-lateral; bottom panels: superior-inferior). Data points (x-axis) are before treatment (baseline), after SMT, after each of the PowerPlate repetitions, and 1 and 2 hours posttreatment. Legend at the bottom right represents chiropractic visits 7 to 11 during the treatment phase. The reference lines are control values that were collected from 2 healthy individuals (short- and long-dashed lines). Solid lines represent means of the accelerometry data acquisition across chiropractic visits, with the error bars representing standard deviations (SD). Notes for mean SD data lines:Visit 7 was an outlier for tremor frequency in the anterior-posterior direction and for maximum accelerations in the medial-lateral and superior-inferior directions, while visit 8 was an outlier for maximum acceleration in the anterior-posterior direction. Outliers were identified as ±2 SD from the mean of the accelerometry data acquisition across chiropractic visits.

The PCP ordered a brain MRI between chiropractic visits 9 and 10 to rule out structural damage (81 days post-MVA). Magnetic resonance imaging findings were unremarkable for structural changes in brain neuroanatomy.

Discharge From Chiropractic Care

At chiropractic visit 10 (81 days post-MVA), the visual observation of truncal tremors showed “mild twitching.” The patient was discharged from care after chiropractic visit 12 (95 days post-MVA) since she reached maximal medical improvement. Truncal tremors were still present, but the patient described them as “barely noticeable.” The patient was able to complete all activities of daily living without interference. The patient was compliant with the stress reduction techniques. The patient self-reported no adverse or unanticipated events to any of the treatment modalities. The patient provided written informed consent for the publication of the case report.

Discussion

This case report describes clinical improvements in truncal tremor characteristics and negative Romberg tests after a course of care with SMT, WBVT, and acupuncture therapy.

Without an organic cause for the truncal tremors, she was prescribed anxiety medications and behavioral therapy, which was consistent with standard medical treatment of FMD.1, 2, 3,7 Early communication about her injury and medical diagnosis to the patient in the ER either may have lacked the explanation that head trauma may result in changes in neural function, which may produce truncal tremors, or it is possible the patient did not recall being told this information.1, 2, 3,5,7 The patient reported she was upset by the neurologist's “psychological diagnosis.” However, after the patient learned that there was no structural damage to her brain, the observation of truncal tremors was reduced. Physical medicine and rehabilitation should include active care with less emphasis on pharmacological interventions.23,24 As well, patient values should be considered when suggesting treatment options. In this case, the prescription of the anxiety medication may not have aligned with the patient's value for conservative treatment. The patient adhered to behavioral interventions, manual therapies, and acupuncture therapy, but she decided to discontinue the use of medications since she perceived no benefits.

The proposed mechanism of manual therapies to treat FMD may include neuromodulation of sensorimotor pathways within the central nervous system that regulate muscle contractions.1, 2, 3,5,7 It is hypothesized that WBVT may have an effect on spasticity and improve gait, balance, and motor function in neurological conditions.25, 26, 27 Biological plausibility for WBVT suggests that changes in afferent firing rates may modulate muscle activation by correcting maladaptation of sensorimotor processing.28,29 Besides neuromodulation, cognitive-behavioral effects of WBVT may include entrainment of tremor frequency or suggestibility.3,6,12 However, variations of WBVT parameters, such as amplitude, frequency, duration, and participant positioning, present a challenge to determining clinical applications and mechanisms of WBVT.25, 26, 27, 28

Previous mechanistic studies on HVLA SMT suggest unique stimulus-response patterns of afferent discharges that alter neuronal activity within spinal, corticospinal, intracortical, and cerebellar pathways.30, 31, 32 These mechanistic studies align with the proposed mechanism of manual therapies to treat FMD. Specifically, changes in neuronal firing patterns following HVLA SMT may alter neuromodulation of sensorimotor pathways within the central nervous system.1, 2, 3,5,7,30, 31, 32 Although a causal relationship between neural plasticity and clinical effectiveness of HVLA SMT remains unknown,30,31,33 clinical recommendations include spinal manipulation/mobilization to treat neck pain and whiplash-associated disorders.34, 35, 36 Acupuncture therapy for FMD lacks sufficient evidence.2

This case study aligns with the clinical presentation, diagnosis, pathophysiology, prognosis, and multimodal treatments of FMD.1, 2, 3,5,7,22 We propose that the patient showed improvement because the characteristics of the patient included satisfaction with chiropractic care and acupuncture therapy, good physical and social health, recent onset, and a medical diagnosis/treatment of anxiety.1,7 The current case included multimodal treatments that aligned with treating the biopsychosocial characteristics of FMD.1, 2, 3 Whole-body vibration therapy, SMT, and acupuncture therapy are safe and well-tolerated by patients.27,37, 38, 39

Limitations

There are limitations to case reports. The multimodal treatments and uncontrolled factors in the patient's life between clinical visits do not allow us to generalize our clinical findings beyond this single patient or draw any conclusions about treatment effectiveness. It is possible that a combination of factors or natural history of the disorder led to the decrease in truncal tremors; thus, there may have been no association with treatment and patient improvement.

Conclusion

The patient reported improvement under a course of chiropractic care using a multimodal approach, including behavioral, pharmacological, and manual therapies. This case study suggests that WBVT, SMT, and acupuncture therapy may assist some patients with FMD.

Funding Sources and Conflicts of Interest

No funding sources or conflicts of interest were reported for this study.

Contributorship Information

Concept development (provided idea for the research): A.F., M.O.P.

Design (planned the methods to generate the results): A.F., M.O.P.

Supervision (provided oversight, responsible for organization and implementation, writing of the manuscript): A.F.

Data collection/processing (responsible for experiments, patient management, organization, or reporting data): A.F., M.O.P.

Analysis/interpretation (responsible for statistical analysis, evaluation, and presentation of the results): A.F., M.O.P.

Literature search (performed the literature search): A.F.

Writing (responsible for writing a substantive part of the manuscript): A.F.

Critical review (revised manuscript for intellectual content, this does not relate to spelling and grammar checking): A.F., M.O.P.

Practical Applications.

-

•

A patient presented with truncal tremors following a motor vehicle accident.

-

•

Manual therapies and a multimodal treatment approach were applied to this patient with a functional movement disorder.

-

•

The case study describes how chiropractic care, whole-body vibration therapy, and acupuncture therapy were included in comanagement of this patient.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.jcm.2023.03.010.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Frucht L, Perez DL, Callahan J, et al. Functional dystonia: differentiation from primary dystonia and multidisciplinary treatments. Front Neurol. 2021;11 doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.605262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.LaFaver K. Treatment of functional movement disorders. Neurol Clin. 2020;38(2):469–480. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2020.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thenganatt MA, Jankovic J. Psychogenic (functional) movement disorders. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2019;25(4):1121–1140. doi: 10.1212/CON.0000000000000755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tisch S. Recent advances in understanding and managing dystonia. F1000Res. 2018;7 doi: 10.12688/f1000research.13823.1. F1000 Faculty Rev-124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Espay AJ, Aybek S, Carson A, et al. Current concepts in diagnosis and treatment of functional neurological disorders. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75(9):1132–1141. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hallett M. Physiology of psychogenic movement disorders. J Clin Neurosci. 2010;17:959–965. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2009.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peckham EL, Hallett M. Psychogenic movement disorders. Neurol Clin. 2009;27(3):801–819. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Albanese A, Sorbo FD. Dystonia and tremor: the clinical syndromes with isolated tremor. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y) 2016;6:319. doi: 10.7916/D8X34XBM. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hallett M. Tremor: pathophysiology. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2014;20(suppl 1):S118–S122. doi: 10.1016/S1353-8020(13)70029-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Panyakaew P, Cho HJ, Lee SW, Wu T, Hallett M. The pathophysiology of dystonic tremors and comparison with essential tremor. J Neurosci. 2020;40(48):9317–9326. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1181-20.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhidayasiri R. Differential diagnosis of common tremor syndromes. Postgrad Med J. 2005;81(962):756–762. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2005.032979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thenganatt MA, Jankovic J. Psychogenic tremor: a video guide to its distinguishing features. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y) 2014;4:253. doi: 10.7916/D8FJ2F0Q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhatia KP, Quinn NP, Marsden CD. Clinical features and natural history of axial predominant adult onset primary dystonia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1997;63(6):788–791. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.63.6.788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ehrlich DJ, Frucht SJ. The phenomenology and treatment of idiopathic adult-onset truncal dystonia: a retrospective review. J Clin Mov Disord. 2016;3:15. doi: 10.1186/s40734-016-0044-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mehta S, Ray S, Chakravarty K, Lal V. Spectrum of truncal dystonia and response to treatment: a retrospective analysis. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2020;23(5):644–648. doi: 10.4103/aian.AIAN_542_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Voos MC, Oliveira Tde P, Piemonte ME, Barbosa ER. Case report: physical therapy management of axial dystonia. Physiother Theory Pract. 2014;30(1):56–61. doi: 10.3109/09593985.2013.799252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Defazio G, Berardelli A, Abbruzzese G, et al. Possible risk factors for primary adult onset dystonia: a case-control investigation by the Italian movement disorders study group. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1998;64(1):25–32. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.64.1.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ellis S. Tremor and other movement disorders after whiplash type injuries. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1997;63(1):110–112. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.63.1.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hawley JS, Weiner WJ. Psychogenic dystonia and peripheral trauma. Neurology. 2011;77(5):496–502. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182287aaf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumar H, Jog M. Peripheral trauma induced dystonia or post-traumatic syndrome? Can J Neurol Sci. 2011;38(1):22–29. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100011057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Young C, Argáez C. Manual Therapy for Chronic Non-cancer Back and Neck Pain: A Review of Clinical Effectiveness. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; Ottawa, ON: 2020. CADTH rapid response reports. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hess CW, Pullman SL. Tremor: cinical phenomenology and assessment techniques. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y) 2012;2 doi: 10.7916/D8WM1C41. tre-02-65-365-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cicerone KD. Evidence-based practice and the limits of rational rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86(6):1073–1074. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gutenbrunner C, Nugraha B. Decision-making in evidence-based practice in rehabilitation medicine: proposing a fourth factor. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2020;99(5):436–440. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000001394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alashram AR, Padua E, Annino G. Effects of whole-body vibration on motor impairments in patients with neurological disorders: a systematic review. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2019;98(12):1084–1098. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000001252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moggio L, de Sire A, Marotta N, Demeco A, Ammendolia A. Vibration therapy role in neurological diseases rehabilitation: an umbrella review of systematic reviews. Disabil Rehabil. 2022;44(20):5741–5749. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2021.1946175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stania M, Juras G, Słomka K, Chmielewska D, Król P. The application of whole-body vibration in physiotherapy - a narrative review. Physiol Int. 2016;103(2):133–145. doi: 10.1556/036.103.2016.2.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bills KB, Clarke T, Major GH, et al. Targeted subcutaneous vibration with single-neuron electrophysiology as a novel method for understanding the central effects of peripheral vibrational therapy in a rodent model. Dose Response. 2019;17(1) doi: 10.1177/1559325818825172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krause A, Gollhofer A, Freyler K, Jablonka L, Ritzmann R. Acute corticospinal and spinal modulation after whole body vibration. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2016;16(4):327–338. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dishman JD, Burke JR, Dougherty P. Motor neuron excitability attenuation as a sequel to lumbosacral manipulation in subacute low back pain patients and asymptomatic adults: a cross-sectional H-reflex study. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2018;41(5):363–371. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2017.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gyer G, Michael J, Inklebarger J, Tedla JS. Spinal manipulation therapy: is it all about the brain? A current review of the neurophysiological effects of manipulation. J Integr Med. 2019;17(5):328–337. doi: 10.1016/j.joim.2019.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lima CR, Martins DF, Reed WR. Physiological responses induced by manual therapy in animal models: a scoping review. Front Neurosci. 2020;14:430. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2020.00430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gevers-Montoro C, Provencher B, Descarreaux M, Ortega de Mues A, Piché M. Neurophysiological mechanisms of chiropractic spinal manipulation for spine pain. Eur J Pain. 2021;25(7):1429–1448. doi: 10.1002/ejp.1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bussières AE, Stewart G, Al-Zoubi F, et al. The treatment of neck pain-associated disorders and whiplash-associated disorders: a clinical practice guideline. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2016;39(8) doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2016.08.007. 523-564.e27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Whalen W, Farabaugh RJ, Hawk C, et al. Best-practice recommendations for chiropractic management of patients with neck pain. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2019;42(9):635–650. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2019.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wong JJ, Shearer HM, Mior S, et al. Are manual therapies, passive physical modalities, or acupuncture effective for the management of patients with whiplash-associated disorders or neck pain and associated disorders? An update of the Bone and Joint Decade Task Force on neck pain and its associated disorders by the OPTIMa collaboration. Spine J. 2016;16(12):1598–1630. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2015.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chan MWC, Wu XY, Wu JCY, Wong SYS, Chung VCH. Safety of acupuncture: overview of systematic reviews. Sci Rep. 2017;7:3369. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-03272-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chaibi A, Stavem K, Russell MB. Spinal manipulative therapy for acute neck pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. J Clin Med. 2021;10(21):5011. doi: 10.3390/jcm10215011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hebert JJ, Stomski NJ, French SD, Rubinstein SM. Serious adverse events and spinal manipulative therapy of the low back region: a systematic review of cases. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2015;38(9):677–691. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2013.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.