Abstract

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is an emerging nosocomial pathogen among hospitalized patients, with high morbidity and mortality rates. The discovery of a novel antibacterial is urgently needed to address this resistance problem. The present study aims to explore the antibacterial potential of three depsidone compounds: 2-clorounguinol (1), unguinol (2), and nidulin (3), isolated from the marine sponge-derived fungus Aspergillus unguis IB1, both in vitro and in silico. The antibacterial activity of all compounds was evaluated by calculating the Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and Minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) against MRSA using agar diffusion and total plate count methods, respectively. Bacterial cell morphology changes were studied for the first time using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Molecular docking, pharmacokinetics analysis, and molecular dynamics simulation were performed to determine possible protein–ligand interactions and the stability of the targeting penicillin-binding protein 2a (PBP2a) against 2-clorounguinol (1). The research findings indicated that compounds 1 to 3 exhibited MIC and MBC values of 2 µg/mL and 16 µg/mL against MRSA, respectively. MRSA cells displayed a distinct shape after the addition of the depsidone compound, as observed in SEM. According to the in silico study, 2-chlorounguinol exhibited the highest binding-free energy (BFE) with PBP2a (-6.7 kcal/mol). For comparison, (E)-3-(2-(4-cyanostyryl)-4-oxoquinazolin-3(4H)-yl) benzoic acid inhibits PBP2a with a BFE less than −6.6 kcal/mol. Based on the Lipinski's rule of 5, depsidone compounds constitute a class of compounds with good pharmacokinetic properties, being easily absorbed and permeable. These findings suggest that 2-chlorounguinol possesses potential antibacterial activity and could be developed as an antibiotic adjuvant to reduce antimicrobial resistance.

Keywords: Depsidone, MIC, MBC, PBP2a, Molecular docking, Molecular dynamics simulations, Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

1. Introduction

The resistance of pathogenic bacteria to antibiotics has become a global problem with severe consequences in treating infectious diseases (Mancuso et al., 2023). The presence of resistant pathogenic bacteria has caused the death rate from bacterial infections to increase by more than 2 million per year (Bérdy, 2012). Staphylococcus aureus is an organism that causes various infections in humans and can adapt to the ability to develop resistance against various antibiotics. More than 50% of Staphylococcus cases worldwide are known to be caused by Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) (Craft et al., 2019, Sreepian et al., 2023).

β-lactam antibiotics are the most used drugs in treating various bacterial infections but are generally no longer effective against MRSA infections. Resistance to β-lactam antibiotics occurs due to changes or mutations in protein-coding genes for the penicillin-binding protein (PBP), which is responsible for peptidoglycan biosynthesis and cell wall formation. The development of S. aureus-resistant strain is attributed to the production of an additional PBP responsible for cross-linking peptidoglycan, known as PBP2a. PBP2a is encoded by the gene MecA, and when overexpressed, it results in low binding affinity of PBPs, leading to resistance against these drugs (Contreras-Martel et al., 2011, Yocum et al., 1979, Zapun et al., 2008). The survival and growth of bacterial cells depend on the stability of peptidoglycan, an essential component of bacterial cell walls. Disrupting the biosynthesis of these proteins can lead to bacterial lysis and death (Contreras-Martel et al., 2011).

The mecA gene is part of the staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) element found in all MRSA strains. Homologs of regulatory genes regulate resistance expression in several MRSA strains. These regulatory genes, such as mecI and mecRI, control the mecA response to β-lactam antibiotics (Arêde et al., 2012, Hiramatsu et al., 1992). The mecR1 and mecI genes encode MecR1 and MecI proteins (Sharma et al., 1998). MecR1 and MecI also have high protein sequence homology with BlaR1 and BlaI proteins, respectively. The genes encoding BlaR1 and BlaI are regulatory genes involved in the induced expression of the β-lactamase (blaZ) gene on the S. aureus plasmid, respectively (Zhang et al., 2001). The blaZ gene shares a similar structure and mechanism with the mecA gene. The carrier regions are sufficiently similar, allowing BlaI to regulate PBP2a expression (Song et al., 1987). Consequently, plasmids carrying the regulatory gene blaZ enable the induction of PBP2a expression under the control of BlaR1 and BlaI, a scenario frequently observed in clinical MRSA isolates (Hackbarth & Chambers, 1993). This protein thus acts on superbugs to inhibit the effectiveness of β-lactam antibiotics.

Identifying potential protein targets for ligand compounds is essential to drug discovery. Recently, computational technology based on molecular docking methods has attracted attention in the target identification processes in silico (Xu et al., 2018). This study employed a molecular docking approach on PBP2a as the primary protein target to identify various ligands as potential antibacterial agents. At the same time, Simultaneously, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was used to study the effect of the ligand on MRSA and to visualize changes on the outer surface of MRSA.

Continuing research worldwide is being conducted to discover and develop new antibacterials for controlling multidrug-resistant bacteria (Miethke et al., 2021; Krishnasamy et al., 2023). Recently, a vast amount of information has become available to predict potential drugs and drug targets efficiently. This includes protein sequences from various strains of the MRSA genome, experimentally determined protein structures, bioinformatics tools for identifying homologous and interacting proteins, computer programs for modeling three-dimensional protein structures, and the docking of small molecule chemical compounds. Identifying protein targets for specific ligands or compounds could be essential to drug discovery (Schenone et al., 2013). Furthermore, several reviews indicate that natural products continue to dominate in providing lead structures and play a vital role in discovering new compounds for drug development. Marine invertebrates and microbes, especially sponges and Actinomycetes, are the most abundant sources of bioactive marine natural products against resistant pathogens (Kersten & Dorrestein, 2009).

As part of our research on antibacterial compounds from marine sponge-derived fungi, we isolated A. unguis IB151 from the sponge Acanthostrongylophora ingens. The ethyl acetate extract of this fungus showed antibacterial activity against Bacillus subtilis, S. epidermidis, Salmonella typosa, and Escherichia coli (Handayani & Aminah, 2017). From this fungus, three depsidones were isolated: 2-chlorounguinol (1), unguinol (2), and nidulin (3). These compounds were also identified in A. unguis WR8, a fungus associated with the marine sponge Haliclona fascigera (Handayani, Rendowati, Aminah, Ariantari, Proksch, et al., 2020). The antibacterial activity of the isolated depsidones was comparable to those previously reported in the literature (Morshed et al., 2018, Morshed et al., 2021). However, this study, for the first time, describes the antibacterial potential of depsidone derivatives through both in vitro and in silico studies.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Aspergillus unguis IB151

The fungus A. unguis IB151 was isolated from the marine sponge Acanthostrongylophora ingens, collected from Mandeh Island in West Sumatra, Indonesia. The molecular identification of the fungus was achieved by analyzing the 18S rRNA region, and the sequence information was deposited in the GenBank under the accession number MZ540143 (Handayani & Aminah, 2017). The fungal strain is preserved in the marine reference collection of the Sumatran Biota Laboratory at Andalas University, Indonesia. The fungus was cultivated using 3.5 kg of rice medium (Kjer et al., 2010).

2.2. Extraction and isolation of antibacterial compounds from Aspergillus unguis IB151

After the fungus had grown for 30–40 days, the medium was extracted with ethyl acetate (EtOAc) and then evaporated under vacuum, yielding a total extract of 49.3 g. The extract was subsequently fractionated using methanol and n-hexane to obtain 26.2 g methanol and 22.9 g n-hexane fractions, respectively. The methanolic fraction underwent separation through vacuum liquid chromatography (VLC) using n-hexane and ethyl acetate as eluents. Seven subtractions were collected, and similar fractions were combined based on color and number of spots displaying the same TLC pattern. Subfractions F1 to F5 appeared as light-yellow oil. F2 was recrystallized using n-hexane and EtOAc, producing compound 1 (251.4 mg) in the form of colorless crystals. The compound IB-02 (56.9 mg) was obtained by passing F3 through a Sephadex LH-20 column with 200 mL of methanol as the eluent. F4 was recrystallized with n-hexane and ethyl acetate, resulting in compound 2 (203.5 mg) in colorless crystals. The structures of these compounds were determined by comparing the spectral data of 2-chlorounguinol, and unguinol to those found in the previous study (Handayani, Rendowati, Aminah, Ariantari, & Proksch, 2020).

The nidulin used in this study has been obtained from the Aspergillus unguis wr8 which was isolated from the marine sponge Haliclona fascigera (Handayani, Rendowati, Aminah, Ariantari, & Proksch, 2020).

2.3. Antibacterial tests (in vitro test)

The clinical isolate MRSA was obtained from M. Djamil Hospital, Padang, Indonesia. Antibacterial properties of 2-chlorounguinol, inguinol, and nidulin were evaluated against MRSA by determining their minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentrations (MBC). This analysis was conducted using a standardized and well-described broth microdilution method as outlined in the M26-A document of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) (Barry et al., 1999). The MIC and MBC values were determined by measuring the growth of MRSA using the broth microdilution method in a 96-well microtiter plate. The procedure involved adding 50 µL of the compound and subsequently diluting vertically, to which 50 µL of bacterial inoculums was added. The inoculum was standardized with McFarland standard 0.5 and horizontally added into the plates. A positive control in this test is the number of test bacterial colonies growing in growth control wells containing Mueller-Hinton (MH) broth. Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h.

Colony growth was assessed using the total plate count (TPC) method. Prior to culturing, the test compounds were diluted to the respective concentration with a bacterial inoculum of 10-7 CFU/mL. The mixture was then homogenized using a vortex, and 100 µL of each mixture was pipetted onto their corresponding Petri dishes containing MH agar medium. The compound-inoculum mixture was spread evenly on the agar medium using the spread plate technique, followed by incubation at 37 ℃ for 24 h. The minimum number of colonies on each Petri dish that inhibited bacterial growth was considered the MIC. Furthermore, after determining the MIC, 100 µL aliquots from each well that exhibited no bacterial growth following incubation were streaked onto MH agar plates and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. The MBC was defined as the lowest concentration that killed 100% of the initial bacterial population, resulting in no colonies on the MH agar medium.

2.4. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis

The SEM analyses were conducted to investigate the morphological changes in MRSA after the antibacterial test (in vitro) treatment, following a modified method described by Murtey and Ramasamy (Murtey & Ramasamy, 2016). The MRSA culture was centrifuged, and the supernatant was discarded. The pellet was then resuspended and fixed with 10% formaldehyde, prepared in 0.1 M phosphate buffer at pH 7.2, for 30 min. Subsequently, the pellet was resuspended in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, centrifuged twice for 10 min, and then washed twice with distilled water for 10 min. The washed sample pellet was dehydrated with ethanol, using a series of concentrations at 35%, 50%, 75%, 95%, and absolute ethanol. It was then placed in a desiccator overnight at room temperature. The dried sample was mounted onto an SEM stub with double-sided sticky tape. Subsequently, the sample was then gold-coated at five mA using a Hitachi E-1045 ion sputter and examined using a Hitachi S-3400 N SEM at a voltage of 15 kV.

2.5. Lipinski's rule of five and ADMET analysis

The druggability of 2-chlorounguinol, unguinol, and nidulin was analyzed based on the criteria determined by Lipinski's rule of five (Ro5). SwissADME (https://www.swissadme.ch) was used to predict ADME parameters, assess the compounds' pharmacokinetic characteristics, and evaluate their drug-like nature.

2.6. Molecular docking analysis

Molecular docking studies were performed using Autodock Vina (Eberhardt et al., 2021, Trott and Olson, 2009) and Glide (Friesner et al., 2006). The 3D configuration of PBP2a with PDB ID: 4CJN was obtained from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB) (Bouley et al., 2015). The 3D SDF file format structure of 2-chlorounguinol (PubChem ID: 6477039) was obtained from the PubChem database. The protein was prepared using OPLS4 force fields integrated into the protein preparation wizard. The molecular docking procedure was carried out using AutoDock Vina v1.2.1 integrated into AMDock (Valdés-Tresanco et al., 2020) v1.5.2 interface. The ligand docking with Glide XP was performed with Schrödinger Maestro v13.3 tools. The analysis and visualization of protein–ligand interaction were performed with PyMOL Molecular Graphics System v2.4.1 and BIOVIA Discovery Studio Visualizer v21.1.0 (Çevik et al., 2022).

2.7. Molecular dynamics simulations

Molecular dynamics simulations (MDS) were conducted using Gromacs v2020.2 (Abraham et al., 2015). The input files required for MD were generated using the default settings of the CHARMM-GUI server (Jo et al., 2008). The amber ff99SB (Lee et al., 2020) was employed for generating topology files. A 65 ns MDS was performed with a time step of 2 fs. The trajectories for RMSD, RMSF, and H-bonds were analyzed using gmx rms, gmx rmsf, and gmx hbond scripts, respectively (Yadav et al., 2023). An animation video of the MDS was produced using PyMOL Molecular Graphics System v2.4.1, and graphical representations were generated with Grace-5.1.22 tools (Celik et al., 2022).

3. Results

3.1. Antibacterial activity of depsidone compounds against MRSA

The depsidone compounds 1 to 3 (Fig. 1) were isolated from the marine-derived fungus Aspergillus unguis. The bacteriostatic activity of these isolated compounds against MRSA was demonstrated in vitro, and the results are presented in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Chemical structures of compounds 2-chlorounguinol (1), unguinol (2), nidulin (3).

Table 1.

Total number of colonies of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bacteria treated in vitro under various concentrations of tested compounds.

| Compounds | Total amount of colonies (CFU/mL) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.25 µg/mL | 0.5 µg/mL | 1 µg/mL | 2 µg/mL | 4 µg/mL | 8 µg/mL | 16 µg/mL | 32 µg/mL | |

| 2-chlorounguinol | 7.2 × 1011 | 7.0 × 1011 | 4.7 × 1011 | 4.5 × 1011 | 2 × 1011 | 8 × 1010 | 3 × 109 | 2.6 × 108 |

| unguinol | 85 × 1010 | 67 × 1010 | 25 × 1010 | 15 × 1010 | 12 × 1010 | 9 × 1010 | 7 × 109 | 1.9 × 108 |

| nidulin | 6.9 × 1011 | 4.5 × 1011 | 3.9 × 1011 | 4 × 1010 | 2 × 1010 | 1 × 1010 | 1 × 109 | 9 × 107 |

| Positive control | Total amount of colonies (CFU/mL) 9.4 × 1011 |

|||||||

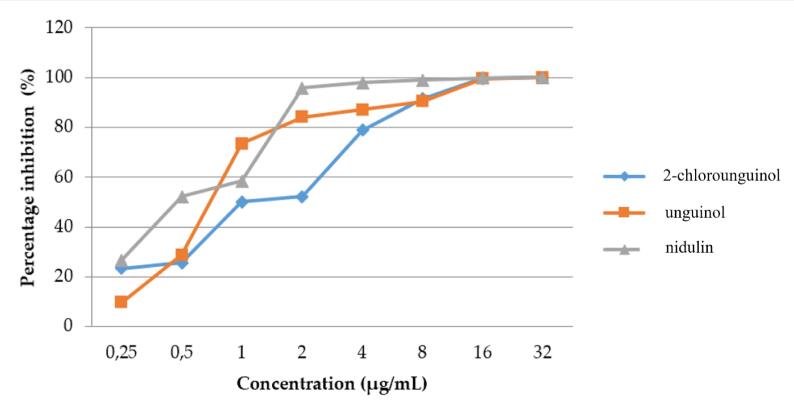

The antibacterial test results revealed that the mean colony count of MRSA treated with all depsidone compounds was lower than that of the positive control (9.4 × 1011 CFU/mL). Fig. 2 demonstrates that the total number of MRSA colonies decreased significantly at various concentration intervals for all compounds.

Fig. 2.

Percentage inhibition of MRSA bacterial colonies treated with various concentrations of 2-chlorounguinol, unguinol, and nidulin.

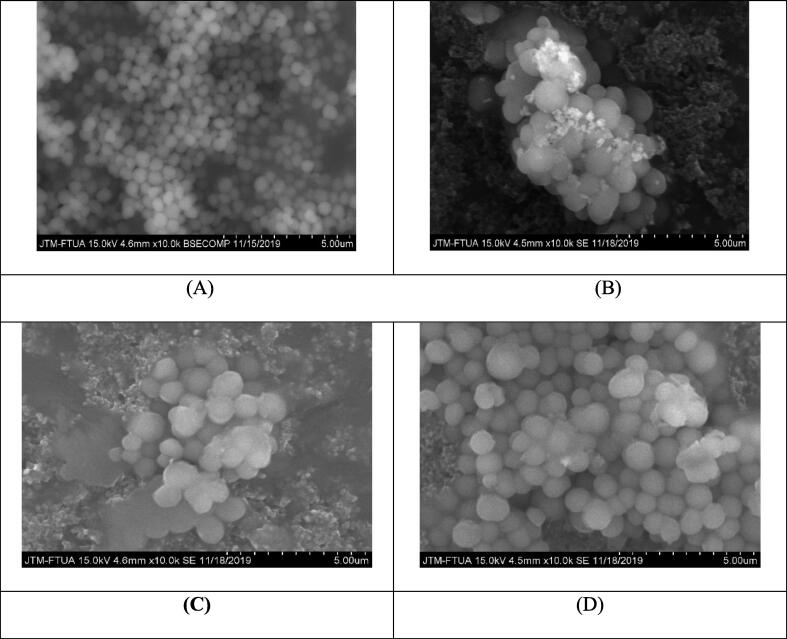

3.2. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis

Considering that these depsidones may inhibit cell wall synthesis, SEM was utilized to visualize the modification of MRSA's outer surface by the compounds. In the presence of the compounds, the cell surface displayed observable changes compared to the control, exhibiting a wrinkled bacterial surface with visible secretions (Fig. 3). Therefore, this suggests that the tested depsidones could increase cell permeability, likely by binding to the PBPs and thereby loosening the cell wall. This effect could also inhibit the expression of PBP2a.

Fig. 3.

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) of MRSA (A) and MRSA following in vitro administration of 2-chlorounguinol (B), unguinol (C), and nidulin (D).

Several studies have shown through SEM analysis that the administration of synthetic compounds, isolated plant compounds, and β-lactam antibiotics (oxacillin, ampicillin, vancomycin, gentamicin, and erythromycin) led to alterations in the surface of MRSA bacteria (Ramos et al., 2006).

3.3. Physicochemical properties of depsidone compounds according to Lipinski's rule of 5 (Ro5)

Furthermore, a compound's physicochemical properties can predict its potential for drug development or druggability, which is essential for assessing its pharmacokinetic qualifications. These fundamental physicochemical properties encompass the compound's molecular weight (MW), the logarithm of the partition coefficient (log P) between the particle and water phases, the number of bonds involving rotating atoms (torsion), hydrogen bond acceptors (HBA), hydrogen bond donors (HBD), and polar surface area (PSA). These properties can be calculated using SwissADME online tools (www.swissadme.ch) (Daina et al., 2017, Lipinski et al., 2012). Table 2 lists the physicochemical properties of the isolated compounds.

Table 2.

Physicochemical properties of depsidone compounds from A. unguis IB151.

| Compounds | Physicochemical Properties |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MW (g/mol) | Log P | Torsion | HBD | HBA | PSA (Å2) | |

| 2-chlorounguinol | 360.79 | 4.30 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 75.99 |

| unguinol | 326.34 | 3.80 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 75.99 |

| nidulin | 443.70 | 5.67 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 64.99 |

Lipinski's Ro5 hypothesizes that a compound might face challenges in drug discovery and development if it exhibits low permeability, a molecular weight exceeding 500 g/mol, and a calculated Log P (CLogP) greater than 5 (or MlogP greater than 4.15) (Lipinski, 2004). In addition, for a compound to be considered “druggable”, it should have no more than five hydrogen bond donors (including OH and NH groups), and the presence of no more than ten hydrogen bond acceptors (including O and N atoms) is permissible (Lipinski et al., 2012).

3.4. Molecular docking analysis

The molecular docking approach predicted the binding-free energy (BFE) released due to the interaction between 2-chlorounguinol, unguinol, nidulin and the target protein PBP2a (Table 3). These results indicate that 2-chlorounguinol is more effective against PBP2a compared to unguinol and nidulin. The BFE of 2-chlorounguinol calculated by AutoDock Vina was −6.7 kcal/mol, while the BFE created by Glide software was −6.4 kcal/mol (Table 4). Although slight discrepancies existed between the BFE values obtained from Vina and Glide for 2-chlorounguinol, the BFE results were consistent. To provide an improved graphical representation of the interactions, Glide was utilized to visualize the bonding types (Fig. 4).

Table 3.

Binding energies and protein–ligand interaction details of PBP2a with 2-chlorounguinol, unguinol, nidulin and (E)-3-(2-(4-cyanostyryl)-4-oxoquinazolin-3(4H)-yl) benzoic acid by AutoDock Vina.

| Compounds | Binding free energy (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|

| 2-chlorounguinol | −6.7 |

| unguinol | −6.6 |

| nidulin | −6.0 |

Table 4.

Binding energies and protein–ligand interaction details of PBP2a with 2-chlorounguinol and (E)-3-(2-(4-cyanostyryl)-4-oxoquinazolin-3(4H)-yl) benzoic acid by AutoDock Vina and Glide XP docking (PDB ID: 4CJN).

| Compounds | Binding free energy (kcal/mol) |

Interactions |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AutoDock Vina | Glide | H bonds | Hydrophobic | |

| 2-chlorounguinol | −6.7 | −6.4 | Gln576 (2.13 Å), Ser598 (1.77 Å) | Gln577, Leu594, Val578, Ser643, Ile595, Phe617, Ile587, Lys597, Ala646, Tyr588, Gly596, Met575 |

| (E)-3-(2-(4-cyanostyryl)-4-oxoquinazolin-3(4H)-yl) benzoic acid | −6.6 | – | Lys316 (2.90 Å) | Asn146, Lys273, His293, Glu294, Ala276, Asp275, Asp295, Tyr316 |

Fig. 4.

The three-dimensional configuration of the molecular docking results obtained from Glide (A) and AutoDock Vina (B) at the PBP2a active site. The two-dimensional (2D) configuration of the interaction of 2-chlorounguinol at the active site of PBP2a shows the hydrogen bonding and other interactions (C).

3.5. Molecular dynamics simulations (MDS)

The MDS results are depicted in Fig. 5. The root-mean standard deviation (RMSD) analysis demonstrated that the movement of 2-chlorounguinol atoms remained stable in the time range from 0.2 to 38 ns, after which atomic movements occured within the range of 0.2–0.5 nm at 40 ns. The motion of the atoms continued to occur within the range of 0.4 to 0.8 nm at 40 ns to 65 ns, as illustrated in Fig. 5A. In addition to the RMSD calculation, the root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) was also shown (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Molecular dynamics simulations' trajectory analysis. (A) The root-mean-square devia-tion (RMSD) plot showing conformational changes of 2-chlorounguinol at the PBP2a active site, (B) The root-mean square fluctuation (RMSF) plot showing the flexibility of PBP2a for each residue, (C) Hydrogen (H) bonds number between 2-chlorounguinol and PBP2a for 65 ns, and (D) Binding poses of 2-chlorounguinol and PBP2a at 50 ns.

RMSF values provide insight into the average atomic structure and fluctuations in protein residue during a specific simulation. These values indicate the potential of compounds or molecules to form bonds, thereby affecting the folding shape of the target protein. RMSF analysis revealed the fluctuations in PBP2A and 2-chlorounguinol amino acid residues within the 0.1 to 0.78 nm range, as depicted in Fig. 5B. Additionally, Fig. 5C illustrates the presence of the hydrogen bonding (H-bonds) between 2-chlorounguinol and PBP2A protein, with a range of 1 to 7 H-bonds observed over a 65 ns simulation duration. However, these H-bonds suggests that only the native substrate or a similar ligand can trigger the allosteric mechanism at the active binding site (Chiang et al., 2020). The results of a 65 ns MDS showed that 2-chlorounguinol remained stable and positioned within the active site region of PBP2A. This is further supported by the findings in Fig. 5D, which demonstrate the continued presence of the compound in the active site region at 50 ns.

4. Discussion

Methicillin-resistant S. aureus has developed resistance to various antibiotic classes, including β-lactams, rendering it multidrug-resistant. Consequently, the development of different antibacterial agents is imperative to combat the circulating resistant bacterial strains. A. unguis IB151, isolated from the sponge A. ingens, exhibits potent antibacterial activity by inhibiting the growth of B. subtilis, S. epidermidis, S. typosa, and E. coli. As a result, this study used disc diffusion and micro-dilution methods to evaluate in vitro antibacterial activity. Furthermore, molecular docking analysis was conducted to investigate the interaction between the ligand (depsidones) and their target protein in MRSA.

The amount of fungus ethyl acetate extract obtained was meager. The methanolic and hexane fractions yielded 0.75 and 0.65% w/w, respectively, relative to the weight of the rice medium used for fungus cultivation. Furthermore, the yields of the antibacterial isolated compounds were 0.096 and 0.022% w/w for 2-chlorounguinol and unguinol, respectively. These results demonstrate that this fungus yielded meager extract, fractions, and isolates.

Percentage inhibition against MRSA was observed at 91.49% for 2-chlorounguinol, 90.43% for unguinol, and 95.74% for nidulin. The high percentage of inhibition was reflected in the potent MIC values of 8 µg/mL, 8 µg/mL, and 2 µg/mL, respectively. The MIC is the lowest concentration of antimicrobial agent that completely inhibits the organism's growth in microdilution wells, as obtained with a lethality percentage of 90% (Ramos et al., 2006). Furthermore, at a concentration of 32 µg/mL, the three compounds reduced the mean count of MRSA colonies by 99.97 to 99.99%. The MBC has been defined as the lowest drug concentration that results in a 98 to 99.9% killing effect of the final inoculum (CLSI, 1998). The reported data suggest that 2-chlorounguinol warrants additional investigation. As the concentration of 2-chlorounguinol increased, there was a significant reduction in the total number of colonies, with a notable decrease from 7.2 × 1011 CFU/mL at the lowest concentration (0.25 µg/mL) to 2.6 × 108 CFU/mL at the highest concentration (32 µg/mL). This consistent trend suggests that 2-chlorounguinol may have a potent inhibitory effect on colony growth. Both unguinol and nidulin demonstrated decreases in colony count as the compound concentration increased. However, the pattern for nidulin exhibited less consistency compared to unguinol. Therefore, further investigation into the mechanisms and properties of 2-chlorounguinol is warranted to gain valuable insights into its potential applications and efficacy as an antibacterial agent. As a result, 2-chlorounguinol was selected for molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation.

The SEM results of the MRSA bacteria's surface before and after depsidone treatment are shown in Fig. 3. Fig. 3A depicts the bacterial cell surface as it would be in the absence of depsidone administration, while Fig. 3B through 3D depicts the altered cell surface as a result of depsidone compound administration. All compounds evaluated in this study are structural derivatives with functional group similarities. 2-Chlorounguinol and unguinol have hydrogen bonds between hydrophilic amino acid residues and could interact with the hydrophobic units of the peptidoglycan. This process disrupts membrane permeability, making it easier for these compounds to enter the cytoplasmic membrane. These compounds accumulate in the cytoplasmic membrane, causing the cell membrane to expand and swell. This swelling process alters the permeability and fluidity of the membrane (Daina et al., 2017).

The isolated depsidone compounds possess weakly acidic hydroxyl groups that can transport monovalent cations across membranes by removing them from the membrane for proton exchange. This process destabilizes the membrane and lowers the membrane potential. The pH value in the membrane will decrease, disrupting the enzyme activities engaged in cell metabolism, including enzymes involved in cell wall synthesis (Ultee et al., 2002).

In compliance with Lipinski law, the isolated depsidones' physicochemical properties follow the expected high permeability and absorption rates. A promising compound's permeability must have a Log Kp value of fewer than 2.5 cm/s (Pires et al., 2015, Potts and Guy, 1992). The log Kp for 2-chlorounguinol, unguinol, and nidulin were −4.79 cm/s, −5.03 cm/s, and −4.18 cm/s, respectively, which were all less than the threshold value for an expected “good” permeability rate.

Molecular docking analysis predicted the interaction of 2-chlorounguinol, unguinol, and nidulin into PBP2a. The residues Asp275, Asp295, Asn146, Lys273, Tyr316, and Lys316 were identified as interacting with the positive control compound (E)-3-(2-(4-cyanostyryl)-4-oxoquinazolin-3(4H)-yl)benzoic acid, serving as a positive comparison for PBP2a. Among the compounds, 2-chlorounguinol and unguinol exhibited the most favorable antibacterial potential on PBP2a of MRSA, as reflected in their BFE. These compounds interacted with residues in a manner similar to the interactions with the native ligand comparator. Notably, hydrogen bonds formed with Lys316. An increase in the strength of the ligand-receptor interaction results in a decrease in the BFE value, as evident from the comparison of BFE values. Beside hydrogen bonds, other interactions also play a role. Both 2-chlorounguinol and unguinol engaged in hydrophobic interaction at Asn146 and Lys273 residues. However, the interaction of hydrogen-bonded interactions, as seen in the 2-chlorounguinol compound, significanlty diminishes the BFE value. This is attributed to the stronger nature of hydrogen bonds compared to van der Waals interactions (aromatic and hydrophobic) (Patrick, 2001).

One study has reported that the allosteric binding domain, located at a distance of 60 Å from the DD-transpeptidase, facilitates the entry of the substrate into the active site (Otero et al., 2013). To examine the efficiency of 2-chlorounguinol and unguinol compounds at allosteric sites, similar molecular docking studies were conducted in this present study with the following residues within the active sites: Asn71, Ser72, Leu73, Gly74, Asn104, Tyr105, Ile142, His143, Ile144, Glu145, Asn146, Leu147, Lys148, Ser149, Lys273, Asp275, Glu294, Asp295, Gly296, Tyr297, Arg298, Val299, Thr300, Ile314, Glu315, Lys316, and Lys318. This investigation employed Schrodinger's tools (Friesner et al., 2006), with ceftobiprole as native ligand. Mechanistic investigations of MRSA have indicated that the antibiotic ceftaroline (Teflaro) binds to the allosteric site of PBP2a and engaged in strong π cation interactions with Lys273 and Lys316 (Rani et al., 2014). In contrast, (E)-3-(3-carboxyphenyl)-2-(4-cyanostyryl)-quinazolin-4(3H)-one extends into the pocket formed by the amino acids Lys316, Lys273, and Glu294, forming two robust hydrogen bonds, particularly with Lys316 and Lys273 (Shalaby et al., 2020).

The PBP2a protein's active site includes the amino acids Lys406, Lys597, Ser598, Glu602, and Met641 (Konaté et al., 2012). Within the active site of PBP2a, 2-chlorouguinol formed hydrogen bonds with Ser598, exhibiting a bond length of 1.77 Å. In addition, a hydrophobic bond was established with Lys597 at the active site. The hydrogen bonding between 2-chlorounguinol and ser598 in PBP2A could influence the conformation of the β-sheet section, particularly the β3 strand. This conformational change in the β3 strand is known to help avoid steric clashes with reactive β-lactams, as seen with the drug ceftobiprole (Lovering et al., 2012). Further research, both in vivo and silico, is warranted to gain deeper understanding of the mechanism of action of depsidones and their potential synergy with other antibiotics.

5. Conclusions

The antibacterial properties of three depsidones (2-chlorounguinol, unguinol, and nidulin), isolated from the marine sponge-associated fungi A. unguis IB151 and A. unguis WR8, exhibited MIC values within susceptibility range of ≤ 8 µg/mL, with the optimal MBC value observed at a concentration of 32 µg/mL. The results of molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation studies indicate that the antibacterial activity of these compounds is directly linked to their interaction with PBP2a, the target protein for MRSA. This interaction suggests their potential for future drug development to treat MRSA infection. Furthermore, SEM analysis shed light on the impact of the isolated depsidones on cell wall biosynthesis, resulting in altered MRSA cell morphology. The predicted physicochemical properties of these compounds highlight their druggability and favorable pharmacokinetic characteristics, making them suitable candidates for further drug discovery and development.

Funding

This work was supported by BOPTN of Andalas University in Padang, Indonesia, for the T/ 1/ UN.16.17/PT.01.03/KO-RPBQ/2022 project.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Dian Handayani: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data curation, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. Ibtisamatul Aminah: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. Purnawan Pontana Putra: Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. Andani Eka Putra: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Supervision, Supervision. Dayar Arbain: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Herland Satriawan: Software, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. Mai Efdi: Validation, Writing – review & editing. Trina Ekawati Tallei: Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgment

The Authors are thankful and would like to acknowledge Universitas Andalas.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

References

- Abraham M.J., Murtola T., Schulz R., Páll S., Smith J.C., Hess B., Lindah E. Gromacs: high-performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX. 2015;1–2:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.softx.2015.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arêde P., Milheiriço C., de Lencastre H., Oliveira D.C. The anti-repressor MecR2 promotes the proteolysis of the mecA repressor and enables optimal expression of β-lactam resistance in MRSA. PLoS Pathogens. 2012;8(7):13. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry, A. L., A., P. W., Nadler, M. D. H., Reller, P. D. L. B., & M.D. Christine C. Sanders, Ph.D. Jana M. Swenson, M. M. S. (1999). M26-A Methods for Determining Bactericidal Activity of Antimicrobial Agents; Approved Guideline This document provides procedures for determining the lethal activity of antimicrobial agents. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 19(September), 1–14.

- Bérdy J. Thoughts and facts about antibiotics: where we are now and where we are heading. J. Antibiot. 2012;65(8):385–395. doi: 10.1038/ja.2012.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouley R., Kumarasiri M., Peng Z., Otero L.H., Song W., Suckow M.A., Schroeder V.A., Wolter W.R., Lastochkin E., Antunes N.T., Pi H., Vakulenko S., Hermoso J.A., Chang M., Mobashery S. Discovery of antibiotic (E)-3-(3-carboxyphenyl)-2-(4-cyanostyryl)quinazolin-4(3 H)-one. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137(5):1738–1741. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b00056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celik I., Abdellattif M.H., Tallei T.E. An insight based on computational analysis of the interaction between the receptor-binding domain of the omicron variants and human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. Biology. 2022;11(5) doi: 10.3390/biology11050797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Çevik U.A., Celik I., Işık A., Pillai R.R., Tallei T.E., Yadav R., Özkay Y., Kaplancıklı Z.A. Synthesis, molecular modeling, quantum mechanical calculations and ADME estimation studies of benzimidazole-oxadiazole derivatives as potent antifungal agents. J. Mol. Struct. 2022;1252 doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2021.132095. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang Y.C., Wong M.T.Y., Essex J.W. Molecular dynamics simulations of antibiotic ceftaroline at the allosteric site of penicillin-binding protein 2a (PBP2a) Isr. J. Chem. 2020;60(7):754–763. doi: 10.1002/ijch.202000012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras-Martel C., Amoroso A., Woon E.C.Y., Zervosen A., Inglis S., Martins A., Verlaine O., Rydzik A.M., Job V., Luxen A., Joris B., Schofield C.J., Dessen A. Structure-guided design of cell wall biosynthesis inhibitors that overcome β-lactam resistance in staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) ACS Chem. Biol. 2011;6(9):943–951. doi: 10.1021/cb2001846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craft K.M., Nguyen J.M., Berg L.J., Townsend S.D. Methicillin-resistant: staphylococcus aureus (MRSA): antibiotic-resistance and the biofilm phenotype. MedChemComm. 2019;10(8):1231–1241. doi: 10.1039/c9md00044e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daina A., Michielin O., Zoete V. SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Rep. 2017;7(March):1–13. doi: 10.1038/srep42717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberhardt J., Santos-Martins D., Tillack A.F., Forli S. AutoDock Vina 1.2.0: new docking methods, expanded force field, and python bindings. J. Chem. Inform. Model. 2021;61(8):3891–3898. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.1c00203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friesner R.A., Murphy R.B., Repasky M.P., Frye L.L., Greenwood J.R., Halgren T.A., Sanschagrin P.C., Mainz D.T. Extra precision glide: docking and scoring incorporating a model of hydrophobic enclosure for protein-ligand complexes. J. Med. Chem. 2006;49(21):6177–6196. doi: 10.1021/jm051256o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackbarth C.J., Chambers H.F. blaI and blaR1 regulate β-lactamase and PBP 2a production in methicillin- resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1993;37(5):1144–1149. doi: 10.1128/AAC.37.5.1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handayani D., Aminah I. Antibacterial and cytotoxic activities of ethyl acetate extract of symbiotic fungi from West Sumatra marine sponge Acanthrongylophora ingens. J. Appl. Pharmaceut. Sci. 2017;7(2):237–240. doi: 10.7324/JAPS.2017.70234. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Handayani, D., Rendowati, A., Aminah, I., Ariantari, N. P., Proksch, P., & Biologie, P. (2020). Bioactive Compounds from Marine Sponge Derived FungusvAspergillus unguis WR8. Rasayan Journal of Chemistry, 13(4), 2633–2638. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.31788/ RJC.2020.1345781.

- Hiramatsu K., Asada K., Suzuki E., Okonogi K., Yokota T. Molecular cloning and nucleotide sequence determination of the regulator region of mecA gene in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) FEBS Lett. 1992;298(2–3):133–136. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80039-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo S., Kim T., Iyer V.G., Im W. CHARMM-GUI: a web-based graphical user interface for CHARMM. J. Comput. Chem. 2008;29(11):1859–1865. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kersten R.D., Dorrestein P.C. Secondary metabolomics: natural products mass spectrometry goes global. ACS Chem. Biol. 2009;4(8):599–601. doi: 10.1021/cb900187p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjer J., Debbab A., Aly A.H., Proksch P. Methods for isolation of marine-derived endophytic fungi and their bioactive secondary products. Nat. Protoc. 2010;5(3):479–490. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konaté K., Mavoungou J.F., Lepengué A.N., Aworet-Samseny R.R.R., Hilou A., Souza A., Dicko M.H., M’Batchi B. Antibacterial activity against β- lactamase producing Methicillin and Ampicillin-resistants Staphylococcus aureus: fractional Inhibitory Concentration Index (FICI) determination. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2012;11:1–12. doi: 10.1186/1476-0711-11-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnasamy G., Azahar M.-S., Rahman S.-N.-S.-A., Vallavan V., Zin N.M., Latif M.A., Hatsu M. Activity of aurisin A isolated from Neonothopanus nambi against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains. Saudi Pharmaceut. J. 2023;31(5):617–625. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2023.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J., Hitzenberger M., Rieger M., Kern N.R., Zacharias M., Im W. CHARMM-GUI supports the Amber force fields. J. Chem. Phys. 2020;153(3) doi: 10.1063/5.0012280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipinski C.A. Lead- and drug-like compounds: the rule-of-five revolution. Drug Discov. Today Technol. 2004;1(4):337–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ddtec.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipinski C.A., Lombardo F., Dominy B.W., Feeney P.J. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2012;64(SUPPL.):4–17. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovering A.L., Gretes M.C., Safadi S.S., Danel F., De Castro L., Page M.G.P., Strynadka N.C.J. Structural insights into the anti-methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) activity of ceftobiprole. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287(38):32096–32102. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.355644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancuso G., Midiri A., Gerace E., Biondo C. Bacterial antibiotic resistance: the most critical pathogens. Pathogens. 2023;12(1):1–14. doi: 10.3390/pathogens12010116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miethke M., Pieroni M., Weber T., Brönstrup M., Hammann P., Halby L., Arimondo P.B., Glaser P., Aigle B., Bode H.B., Moreira R., Li Y., Luzhetskyy A., Medema M.H., Pernodet J.L., Stadler M., Tormo J.R., Genilloud O., Truman A.W., Müller R. Towards the sustainable discovery and development of new antibiotics. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2021;5(10):726–749. doi: 10.1038/s41570-021-00313-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morshed M.T., Vuong D., Crombie A., Lacey A.E., Karuso P., Lacey E., Piggott A.M. Expanding antibiotic chemical space around the nidulin pharmacophore. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2018;16(16):3038–3051. doi: 10.1039/c8ob00545a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morshed M.T., Nguyen H.T., Vuong D., Crombie A., Lacey E., Ogunniyi A.D., Page S.W., Trott D.J., Piggott A.M. Semisynthesis and biological evaluation of a focused library of unguinol derivatives as next-generation antibiotics. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2021;19(5):1022–1036. doi: 10.1039/d0ob02460k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murtey M.D., Ramasamy P. Sample preparations for scanning electron microscopy – Life sciences. Modern Electron Microsc. Phys. Life Sci. 2016 doi: 10.5772/61720. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Otero, L. H., Rojas-Altuve, A., Llarrull, L. I., Carrasco-López, C., Kumarasiri, M., Lastochkin, E., Fishovitz, J., Dawley, M., Hesek, D., Lee, M., Johnson, J. W., Fisher, J. F., Chang, M., Mobashery, S., & Hermoso, J. A. (2013). How allosteric control of Staphylococcus aureus penicillin binding protein 2a enables methicillin resistance and physiological function. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 110(42), 16808–16813. 10.1073/pnas.1300118110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Patrick G. In BIOS Scientific Publisher; Oxford: 2001. Instant notes in medicinal chemistry. [Google Scholar]

- Pires D.E.V., Blundell T.L., Ascher D.B. pkCSM: predicting small-molecule pharmacokinetic and toxicity properties using graph-based signatures. J. Med. Chem. 2015;58(9):4066–4072. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potts R.O., Guy R.H. Predicting skin permeability. Pharmaceut. Res.: official J. Am. Assoc. Pharmaceut. Scient. 1992;9(5):663–669. doi: 10.1023/A:1015810312465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos F.A., Takaishi Y., Shirotori M., Kawaguchi Y., Tsuchiya K., Shibata H., Higuti T., Tadokoro T., Takeuchi M. Antibacterial and antioxidant activities of quercetin oxidation products from yellow onion (Allium cepa) skin. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006;54(10):3551–3557. doi: 10.1021/jf060251c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rani N., Vijayakumar S., Thanga Velan L.P., Arunachalam A. Quercetin 3-O-rutinoside mediated inhibition of PBP2a: computational and experimental evidence to its anti-MRSA activity. Mol. BioSyst. 2014;10(12):3229–3237. doi: 10.1039/c4mb00319e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenone M., Dančík V., Wagner B.K., Clemons P.A. Target identification and mechanism of action in chemical biology and drug discovery. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2013;9(4):232–240. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalaby M.A.W., Dokla E.M.E., Serya R.A.T., Abouzid K.A.M. Penicillin binding protein 2a: an overview and a medicinal chemistry perspective. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020;199 doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma V.K., Hackbarth C.J., Dickinson T.M., Archer G.L. Interaction of native and mutant MecI repressors with sequences that regulate mecA, the gene encoding penicillin binding protein 2a in methicillin-resistant staphylococci. J. Bacteriol. 1998;180(8):2160–2166. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.8.2160-2166.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song M.D., Wachi M., Doi M., Ishino F., Matsuhashi M. Evolution of an inducible penicillin-target protein in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus by gene fusion. FEBS Lett. 1987;221(1):167–171. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)80373-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sreepian, P. M., Rattanasinganchan, P., & Sreepian, A. (2023). Antibacterial efficacy of Citrus hystrix (makrut lime) essential oil against clinical multidrug-resistant methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus isolates. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal, xxxx. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsps.2023.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Trott O., Olson A.J. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2009 doi: 10.1002/jcc.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdés-Tresanco M.S., Valdés-Tresanco M.E., Valiente P.A., Moreno E. AMDock: a versatile graphical tool for assisting molecular docking with Autodock Vina and Autodock4. Biol. Direct. 2020;15(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s13062-020-00267-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X., Huang M., Zou X. Docking-based inverse virtual screening: methods, applications, and challenges. Biophys. Rep. 2018;4(1):1–16. doi: 10.1007/s41048-017-0045-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav R., Nath U.K., Celik I., Handu S., Jain N., Dhamija P. Identification and in-vitro analysis of potential proteasome inhibitors targeting PSMβ5 for multiple myeloma. Biomed. Pharmacother. = Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023;157 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yocum, R. R., Waxman, D. J., Rasmussen, J. R., & Strominger, J. L. (1979). Mechanism of penicillin action: Penicillin and substrate bind covalently to the same active site serine in two bacterial D-alanine carboxypeptidases. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 76(6), 2730–2734. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.76.6.2730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zapun A., Contreras-Martel C., Vernet T. Penicillin-binding proteins and β-lactam resistance. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2008;32(2):361–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2007.00095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H.Z., Hackbarth C.J., Chansky K.M., Chambers H.F. A proteolytic transmembrane signaling pathway and resistance to β-lactams in staphylococci. Science. 2001;291(5510):1962–1965. doi: 10.1126/science.1055144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]