Abstract

Near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) presents great potential in the identification of food adulteration due to its advantages of nondestructive, simple, and easy to operate. In this paper, a method based on NIRS and chemometrics was proposed to predict the content of common buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum Moench) flour in Tartary buckwheat (Fagopyrum tataricum (L.) Gaertn) flour. Partial least squares regression (PLSR) and support vector regression (SVR) models were used to analyze the spectrum data of adulterated samples and predict the adulteration level. Various preprocessing methods, parameter-optimization methods, and competitive adaptive reweighted sampling (CARS) wavelength-selection methods were used to optimize the model prediction accuracy. The results of PLSR and SVR modeling for predicting of Tartary buckwheat adulteration content were satisfactory, and the correlation coefficients of the optimum identification models were above 0.99. In conclusion, the combinations of NIRS and chemometrics indicated excellent predictive performance and applicability to analyze the adulteration of common buckwheat flour in Tartary buckwheat flour. This work provides a promising method to identify the adulteration of Tartary buckwheat flour and results obtained can give theoretical and data support for adulteration identification of agro-products.

Keywords: Tartary buckwheat, Near-infrared spectroscopy, Adulteration, Feature wavelengths, Preprocessing

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Adulteration of Tartary buckwheat flour was identified by NIRS and chemometrics.

-

•

Quantitative model of the adulterated degree of Tartary buckwheat was developed.

-

•

Common buckwheat content could be accurately predicted by PLSR and SVR modeling.

-

•

Correlation coefficients of the optimum identification models all exceeded 0.99.

1. Introduction

Although there are wide varieties of buckwheat, there are two cultivated species that are of agricultural significance, and one is common buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum Moench), the other is Tartary buckwheat (Fagopyrum tataricum (L.) Gaertn) (He et al., 2019). Tartary buckwheat flour has similar appearance to common buckwheat flour, but the flavonoid content in common buckwheat is much lower than that of Tartary buckwheat (Li et al., 2019). Owing to the high edible value and nutritional value of Tartary buckwheat, it is favored by consumers with a large market demand. However, to reduce costs and obtain higher profits, some unscrupulous merchants add common buckwheat to Tartary buckwheat or directly mimic Tartary buckwheat. The addition of low-quality substances including common buckwheat reduces the nutritional value of Tartary buckwheat and disturbs the normal market order, thereby negatively affecting the interest of consumers (Zuo et al., 2014).

Ultraviolet and visible spectroscopy (UV–Vis) (Popa et al., 2020), real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) (Li et al., 2021), metabolomics (Li et al., 2022), chromatography (Dou et al., 2022), gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) (Shi et al., 2021), and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (Gunning et al., 2023) are extensively used to identify food adulteration. A multiplex RT-PCR assay has been developed to distinguish Tartary buckwheat from common buckwheat (Kim et al., 2023). A metabolomics approach based on ultra-high performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) coupled to triple quadrupole mass spectrometry was proposed to identify the metabolites in Tartary buckwheat and common buckwheat seeds (Li et al., 2022). The chromatographic fingerprint of Tartary buckwheat flour is established by UPLC to distinguish adulterated Tartary buckwheat from pure Tartary buckwheat (Wang et al., 2016). The key aroma compounds in Tartary buckwheat were characterized by GC-MS combined with means of sensory-directed flavor analysis (Shi et al., 2021). The adulteration of saffron was identified by 60 MHz nuclear magnetic resonance hydrogen spectrum (Gunning et al., 2023). The results of these methods are relatively direct and accurate, but they also have the shortcomings of complicated operation, high cost, large workload, and poor timeliness. Therefore, establishing a rapid, accurate, simple, and efficient analytical technique to identify the adulteration of Tartary buckwheat flour is urgent.

Near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) has the advantages of rapidity, nondestructive nature, easy operation, and high repeatability. NIRS-related techniques combined with chemometrics are extensively used in grain, spices, meat products, tea, and other fields (Lima et al., 2020; Firmani et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2019). Partial least squares regression (PLSR) can solve the multicollinearity of variables in chemometrics. It is suitable for the problem that the number of variables is greater than the sample size. PLSR realizes regression modeling and data-structure simplification by combining model and epistemic methods as the most commonly used quantitative analysis method (Leng et al., 2021). Portable NIRS combined with PLSR has also been adopted to detect the adulteration level in quinoa flour (Wang et al., 2022).

Moreover, support vector regression (SVR) maps nonlinear data to high-dimensional space through kernel function (radial basis function, RBF) and enable linear separability of data. Then, the principle of minimizing structural risk is adopted to process the data (Park et al., 2015). For the prediction problem of small samples, the SVR model has better prediction effect. The quantitative prediction of cyclic adenosine phosphate content in jujube by NIRS has been reported, and results showed that NIRS combined with SVR could greatly improve the prediction performance and stability of the quantitative model (Chen et al., 2019).

More studies on the adulteration identification of Tartary buckwheat by NIRS are necessary and have excellent scientific significance and promising applications. In the present study, NIRS combined with PLSR and SVR algorithms were used to construct quantitative prediction models for the adulteration of common buckwheat flour in Tartary buckwheat flour. Meanwhile, the effects of various preprocessing methods, parameter-optimization methods, and competitive adaptive reweighted sampling (CARS) feature variables selection on the model's prediction accuracy were explored. An accurate and simple method of identifying Tartary buckwheat adulteration was established, providing new insights into the quality control of Tartary buckwheat.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Sample preparation and spectral collection

2.1.1. Samples preparation

The experimental samples were Tartary buckwheat (Fagopyrum tataricum (L.) Gaertn) from Inner Mongolia, Sichuan, and Shanxi and common buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum Moench) from Shaanxi, for a total of four representative buckwheat samples (provided by Zhengzhou Duofuduo Co., Ltd.). The buckwheat rice was cleaned and smashed through an 80-mesh sieve, and then the sample was placed in an electrothermal constant-temperature blast-drying oven at 60 °C to dry until constant weight. The buckwheat flour was directly passed through an 80-mesh sieve, sealed in a bag with a number, and stored at −20 °C.

After grinding and sieving the above Tartary buckwheat samples, they were fully mixed with different proportions of common buckwheat samples as follows: 0% (pure Tartary buckwheat), 5%, 10%, 20%, 30%, 40%, 50%, 60%, 70%, 80%, 90%, and 100% (pure common buckwheat) (Wang et al., 2018). Each proportion of samples was configured with 50 copies for a total of 1800 samples (Chen et al., 2018; Wu et al., 2017). They were sealed in a bag and stored at −20 °C for later use. Before spectrum collection, the sample was put into a centrifugal tube and homogenized for 2 min by point-motion mixing instrument (LC-Vortex-P1, Shanghai Lichen Bangxi Instrument Technology Co., Ltd.) to minimize the possible dispersion effect inherent in particle size and ensure sample uniformity.

2.1.2. Spectrum collection

The samples were collected using an FX 2000 near-infrared spectrometer (room temperature, 25 °C; humidity, 60%). The blank collection was used as the measurement background. The samples were weighed and placed in a sample cup to avoid gaps. Morpho software was used to collect the spectral data of the samples. The instrument process parameters were set. The wavelength-acquisition range was 900–1700 nm, the resolution was 7.8 nm, and the integration time was set to 20 ms. Three parallel spectra were collected for each sample, and each scan was repeated 32 times. The NIRS data of pure Tartary buckwheat samples and adulterated Tartary buckwheat samples were collected by the same method. After collecting three stable spectra, the average spectra were taken as the final spectra. In this experiment, the set partitioning based on joint x-y distance algorithm was used to randomly select the calibration set and prediction set of the spectral data of the Tartary buckwheat samples according to the ratio of 5:1 (Zhou et al., 2020; Khamsopha et al., 2021). The calibration-set samples were used to establish the model, and the prediction set samples were used to verify the model accuracy. The NIRS data of the samples were analyzed and processed by MATLAB program (R2018b).

2.2. Preprocessing of spectral data

As a secondary analysis technology, NIRS spectrum contains rich information of the analytes. Furthermore, the characteristics of serious band overlap, poor specificity of spectral information, and low signal-to-noise ratio necessitate spectrum preprocessing before establishing the model to eliminate the influence of spectral offset or baseline change on the model.

The spectral data were averaged and preprocessed by MATLAB (R2018b). The following preprocessing methods were selected: Standard normal variate (SNV), multiplicative scatter correction (MSC), min–max normalization (MMN), Savitzky–Golay filtering (SG), SG filtering first derivative (SG-1st), SG filtering second derivative (SG-2nd), and SNV transformation and detrending (SNV-DT) (Li et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2019). Appropriate preprocessing methods can improve the stability of the quantitative model.

2.3. Selection of feature wavelengths

The appropriate variable-selection method can eliminate the redundant variables in the spectrum and simplify the model to improve its accuracy. The feature-wavelength-selection method was used to eliminate ineffective information in the spectral data that affect the prediction ability of the model. The effective information was then extracted from the complex spectral information as modeling variables to establish an efficient and stable mathematical model. CARS algorithm can effectively reduce the influence of collinear variables while removing non-informative variables. CARS method was further used to screen certain wavelengths representing the main information of the raw spectrum and preprocessed data, and then a quantitative analysis model was constructed according to the feature variables.

2.4. Model establishment

PLSR and SVR were used as modeling methods to predict the adulteration content of Tartary buckwheat flour. To evaluate the accuracy, applicability, and stability of the quantitative prediction model more accurately and intuitively, the determination coefficient of calibration (R2c), determination coefficient of prediction (R2p), root-mean-square error of calibration (RMSEC), and root-mean-square errors of prediction (RMSEP) were regarded as the main evaluation indices. The larger the R2p was, the closer it was to 1, indicating that the correlation between the measured value and the predicted value was better, and the higher the accuracy of the model. The RMSEC and RMSEP values evaluate the accuracy of the prediction results of the calibration set and prediction set, and the smaller the values were, the closer the predicted value of the sample was to the real value, the higher the prediction accuracy of the model was. The performance of the model was evaluated on the basis of fitting degree and accuracy, and the linear-fitting degree of the regression model was evaluated by comparing the real adulteration value with the predicted one (Mahgoub et al., 2020). When the correlation coefficient R2p of the model exceeded 0.8, it was considered suitable for accurate prediction (Zhang et al., 2014). The R2p was higher than 0.99, the slope was close to 1, and the intercept value was close to 0, indicating that the prediction performance of the model was better and the linearity was higher (Santos et al., 2016).

2.5. Parameter optimization

Based on SVR algorithm modeling, RBF kernel function was selected, including penalty parameter C and kernel parameter g. The set range was (0.1, 1024) The parameters greatly influence the process of modeling, and the prediction ability of the model built by different parameters differs. When using SVR algorithm for modeling, the parameters set or obtained were probably not optimum or close to the optimum, and too large parameters can easily lead to overfitting of the model. Too small also led to model underfitting, so optimizing the parameters was necessary to obtain a better prediction model (Sun et al., 2021). In this experiment, cross-validation (CV), genetic algorithm (GA), and particle swarm optimization algorithm (PSO) were selected to optimize the parameter combination (C, g), determine the optimum parameter combination, and establish a SVR model with strong prediction ability.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. NIRS acquisition and data preprocessing

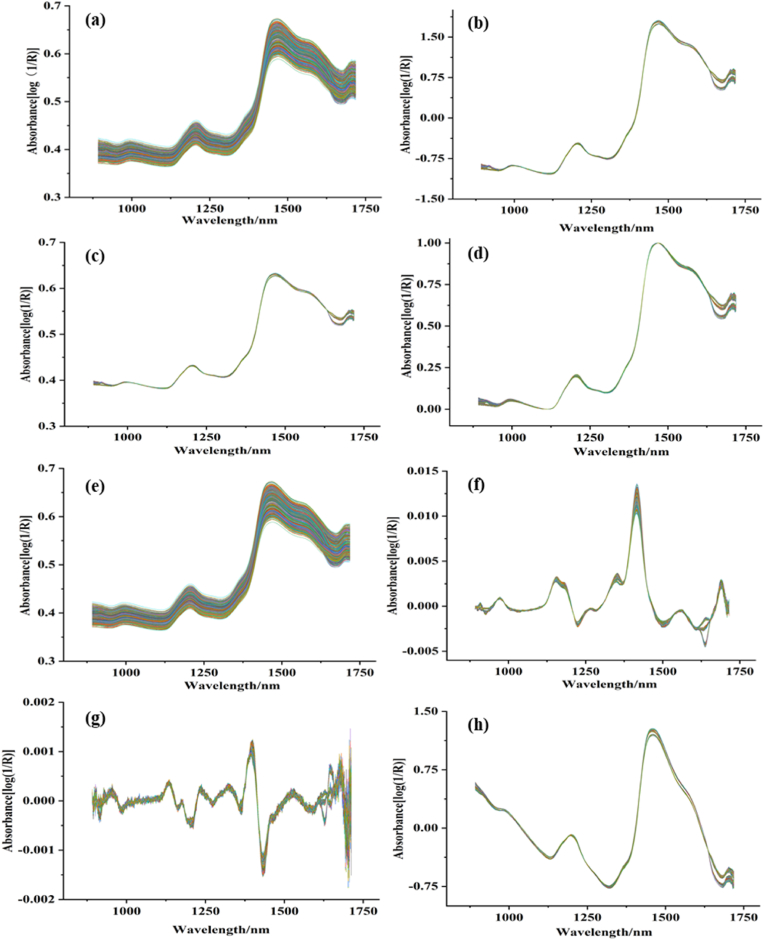

Fig. 1(a), S1a, and S2a are the raw spectral curves of 1800 samples of three kinds of Tartary buckwheat mixed with 12 proportions of Shaanxi common buckwheat. The characteristic absorption peaks of the spectral curves were basically the same, and the overlap was relatively large. The NIRS primarily revealed the composition and content of the sample. The raw NIRS produced baseline drift and noise owing to the interference of various factors (light, particle size, density, surface texture, and other physical factors). Therefore, appropriate spectral preprocessing was necessary to highlight the differences caused by dopants.

Fig. 1.

Raw and preprocessing spectra of Tartary buckwheat in Inner Mongolia: (a) RAW, (b) SNV, (c) MSC, (d) MMN, (e) SG, (f) SG-1st, (g) SG-2nd, and (h) SNV-DT.

The NIRS curves of the seven preprocessing methods of SNV, MSC, MMN, SG, SG-1st, SG-2nd and SNV-DT are shown in Fig. 1(b–h), S1(b–h), and S2(b–h). Many overlaps existed in the spectral curves after preprocessing, and distinguishing the spectral differences between pure and adulterated Tartary buckwheat samples was difficult. Therefore, the purity of Tartary buckwheat must be further quantified by regression model. Accordingly, PLSR and SVR were used to establish quantitative models, and the influence of spectral preprocessing methods on modeling results was analyzed.

3.2. PLSR model performance

3.2.1. Full-spectrum PLSR model

After preprocessing the NIRS data, the PLSR full-spectrum model was constructed. The model prediction results are shown in Table 1. In addition to the poor modeling effect of SG, SG-1st, and SG-2nd for Sichuan Tartary buckwheat samples, the R2p of the full-spectrum PLSR model established by other preprocessing methods reached more than 0.99, and the prediction performance of the model was enhanced. Notably, the prediction performance of the model after SG, SG-1st, and SG-2nd preprocessing decreased, which may be due to the preprocessing-induced loss of effective information in the spectral data or to the noise in the test area causing baseline offset. Ultimately, the model's prediction performance decreased (Liu et al., 2019).

Table 1.

Prediction results of PLSR models under different preprocessing of Tartary buckwheat from Inner Mongolia, Sichuan and Shanxi.

| Preprocessing methods | Number of variables | Inner Mongolia |

Sichuan |

Shanxi |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optimal factor number | Calibration set |

Prediction set |

Optimal factor number | Calibration set |

Prediction set |

Optimal factor number | Calibration set |

Prediction set |

||||||||

| R2c | RMSEC | R2p | RMSEP | R2c | RMSEC | R2p | RMSEP | R2c | RMSEC | R2p | RMSEP | |||||

| RAW | 256 | 13 | 0.9987 | 0.0163 | 0.9984 | 0.0183 | 13 | 0.9932 | 0.0382 | 0.9910 | 0.0407 | 11 | 0.9972 | 0.0244 | 0.9977 | 0.0223 |

| SNV | 256 | 11 | 0.9989 | 0.0154 | 0.9986 | 0.0170 | 11 | 0.9922 | 0.0393 | 0.9902 | 0.0448 | 9 | 0.9967 | 0.0255 | 0.9973 | 0.0251 |

| MSC | 256 | 10 | 0.9988 | 0.0160 | 0.9986 | 0.0168 | 11 | 0.9922 | 0.0393 | 0.9901 | 0.0449 | 9 | 0.9967 | 0.0255 | 0.9973 | 0.0250 |

| MMN | 256 | 11 | 0.9988 | 0.0160 | 0.9987 | 0.0158 | 13 | 0.9926 | 0.0385 | 0.9918 | 0.0403 | 10 | 0.9967 | 0.0257 | 0.9980 | 0.0219 |

| SG | 256 | 13 | 0.9987 | 0.0169 | 0.9982 | 0.0192 | 12 | 0.9922 | 0.0409 | 0.9907 | 0.0420 | 11 | 0.9969 | 0.0255 | 0.9977 | 0.0224 |

| SG-1st | 256 | 13 | 0.9988 | 0.0163 | 0.9991 | 0.0140 | 14 | 0.9934 | 0.0363 | 0.9851 | 0.0487 | 8 | 0.9967 | 0.0252 | 0.9937 | 0.0332 |

| SG-2nd | 256 | 212 | 0.9992 | 0.0127 | 0.9974 | 0.0236 | 156 | 0.9954 | 0.0299 | 0.9759 | 0.0606 | 73 | 0.9984 | 0.0180 | 0.9966 | 0.0267 |

| SNV-DT | 256 | 10 | 0.9988 | 0.0158 | 0.9986 | 0.0168 | 11 | 0.9922 | 0.0392 | 0.9874 | 0.0489 | 9 | 0.9967 | 0.0254 | 0.9975 | 0.0241 |

In the adulteration analysis of Inner Mongolia Tartary buckwheat, the model obtained by SG-1st algorithm had the highest accuracy, with R2p and RMSEP reaching 0.9991 and 0.014, respectively. In the adulteration analysis of Sichuan Tartary buckwheat, the model obtained by MMN algorithm was better than that of the PLSR model established by the raw spectrum, and the accuracy was the highest, with R2p and RMSEP reaching 0.9918 and 0.0403, respectively. Similarly, in the adulteration analysis of Shanxi Tartary buckwheat, the PLSR model obtained by MMN preprocessing surpassed the PLSR model established by the raw spectrum, with the highest accuracy R2p of 0.9980 and RMSEP of 0.0219. These results indicated that PLSR model can be used to determine the purity of Tartary buckwheat.

Fig. 2, S3, and S4 show the distribution of predicted residuals sum of squares (PRESS) in the PLSR model under different preprocessing methods of the calibration set of Tartary buckwheat samples. These samples were of various proportions and originated from Inner Mongolia, Sichuan, and Shanxi. Fig. 2(f) shows the distribution of PRESS in the SG-1st-PLSR model of Tartary Buckwheat calibration set in Inner Mongolia. With increased number of factors, the PRESS decreased continuously. When the number of factors was 13, the PRESS reached the minimum 0.2225. With increased number of factors, the value of PRESS tended to stabilize, showing that the number of factors under the minimum PRESS was the optimum (Zhou et al., 2020). In the process of establishing a PLSR model, the number of factors selected by the model greatly influenced the model accuracy. A fewer number of factors corresponded with less impact of the model, but it may have also led to a decline in model accuracy. A greater number of factors corresponded with more comprehensive points calculated by the model and greater closeness to the actual situation. However, a large number of factors may not only increase the computational complexity of the model, but also increase the number of variables with low or no correlation, leading to overfitting of analysis results (Yan et al., 2019). The optimum factor number of the model after SG-2nd preprocessing was large, which may lead to the phenomenon of model overfitting, as reflected in the large R2c. Conversely, SG-2nd was no longer used in the subsequent modeling because R2p was too small.

Fig. 2.

Changes in PRESS value of the PLSR model under different preprocessing methods of Inner Mongolia Tartary buckwheat:(a) RAW, (b) SNV, (c) MSC, (d) MMN, (e) SG, (f) SG-1st, (g) SG-2nd, and (h) SNV-DT.

Compared with previous results, ours performed better. A real-time quantitative detection method was established for adulterated corn oil, rapeseed oil, and sunflower seed oil in camellia oil based on NIRS and chemometrics (Du et al., 2021). After optimization with different preprocessing methods such as SNV, MSC, SG, and MMN, the quantitative prediction model of PLSR was constructed. R2p was greater than 0.995, RMSEC and RMSEP were less than 6.79 and 4.98, respectively, and the prediction performance of adulteration level of camellia oil was better. PLSR model was also performed to detect the adulteration ability of coconut sugar with different concentrations in palm sugar by using MSC preprocessing spectrum. The model R2p was 0.91 and RMSEP was 9.13%. These results demonstrated the potential of NIRS for food adulteration identification (Rismiwandira et al., 2021). However, many redundant variables existed among the 256 variables in the full spectrum, and the construction of PLSR model took a long time. Therefore, further optimizing the prediction model and extracting feature variables was necessary to improve the discriminant accuracy and modeling efficiency.

3.2.2. Non-full-spectrum PLSR model

To eliminate redundant variables in the NIRS and improve the stability and accuracy of the PLSR prediction model, CARS algorithm was used to simplify the model. According to the NIRS data after different preprocessing methods, a non-full-spectrum PLSR model was established. The model parameters and prediction results are shown in Table 2. After CRAS screening, only SNV, MSC, MMN, and SNV-DT combined with PLSR model showed significant improvement in prediction correlation coefficient, among which the model established after MSC preprocessing had better prediction ability and was superior to the full-spectrum MSC-PLSR model. The MMN-CARS-PLSR model showed higher accuracy than other preprocessing models in the adulteration analysis of Tartary buckwheat in Inner Mongolia, with an R2p of 0.9988 and RMSEP of 0.0152. MSC-CARS-PLSR model showed better performance in the adulteration analysis of Tartary buckwheat from Sichuan, with an R2p of 0.9924 and RMSEP of 0.04. For the adulteration analysis of Shanxi Tartary buckwheat, the SNV-DT-CARS-PLSR model showed better prediction performance, with an R2p of 0.9976 and RMSEP of 0.0235. The selection of feature wavelengths improved the generalization ability of the model, indicating that the CARS method had a certain effect on extracting the effective information of spectral data. CARS-PLSR was used to conduct quantitative analysis of sesame oil adulteration, and found that the model based on variable selection of CARS was superior to the all-spectrum model after comparing the RMSE values of the models (Chen et al., 2018). It was also reported that PLSR was presented to establish a quantitative analysis model for two low-cost adulterants (maltodextrin and starch) in hawthorn fruit flour. Results showed that the PSO-CARS-PLSR model showed good predictive performance, with R2p reaching 0.993 and RMSEP 0.65 (Sun et al., 2021). CARS-PLS model was also the optimum model for quantifying the content of adulterated lotus stamens and corn stigmas in saffron (Li et al., 2020). The above studies confirmed the feasibility of CARS for screening feature variables when using PLSR to construct models.

Table 2.

Prediction results of PLSR models of Tartary buckwheat from Inner Mongolia, Sichuan and Shanxi under different preprocessing after CARS screening.

| Preprocessing methods | Inner Mongolia |

Sichuan |

Shanxi |

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of variables | Optimal factor number | Calibration set |

Prediction set |

Number of variables | Optimal factor number | Calibration set |

Prediction set |

Number of variables | Optimal factor number | Calibration set |

Prediction set |

|||||||

| R2c | RMSEC | R2p | RMSEP | R2c | RMSEC | R2p | RMSEP | R2c | RMSEC | R2p | RMSEP | |||||||

| RAW | 26 | 9 | 0.9986 | 0.0173 | 0.9984 | 0.0182 | 35 | 10 | 0.9923 | 0.0406 | 0.9879 | 0.0480 | 39 | 9 | 0.9970 | 0.0251 | 0.9975 | 0.0234 |

| SNV | 35 | 8 | 0.9988 | 0.0160 | 0.9985 | 0.0174 | 37 | 8 | 0.9919 | 0.0399 | 0.9913 | 0.0424 | 39 | 7 | 0.9967 | 0.0254 | 0.9970 | 0.0263 |

| MSC | 29 | 6 | 0.9987 | 0.0166 | 0.9987 | 0.0167 | 35 | 8 | 0.9917 | 0.0404 | 0.9924 | 0.0400 | 39 | 7 | 0.9967 | 0.0256 | 0.9976 | 0.0240 |

| MMN | 32 | 7 | 0.9987 | 0.0168 | 0.9988 | 0.0152 | 35 | 10 | 0.9916 | 0.0408 | 0.9900 | 0.0438 | 35 | 8 | 0.9966 | 0.0260 | 0.9978 | 0.0227 |

| SG | 32 | 10 | 0.9986 | 0.0174 | 0.9775 | 0.0669 | 39 | 10 | 0.9921 | 0.0411 | 0.9903 | 0.0430 | 29 | 9 | 0.9968 | 0.0257 | 0.9975 | 0.0234 |

| SG-1st | 44 | 7 | 0.9984 | 0.0186 | 0.9633 | 0.0868 | 47 | 27 | 0.9908 | 0.0427 | 0.9805 | 0.0550 | 42 | 5 | 0.9965 | 0.0263 | 0.9924 | 0.0373 |

| SNV-DT | 41 | 7 | 0.9987 | 0.0163 | 0.9984 | 0.0175 | 55 | 8 | 0.9914 | 0.0412 | 0.9902 | 0.0432 | 51 | 8 | 0.9969 | 0.0249 | 0.9976 | 0.0235 |

3.3. SVR model performance

3.3.1. Full-spectrum SVR model

Based on SVR algorithm modeling, RBF kernel function was selected. CV, GA, and PSO were also selected to optimize the parameter combination (C, g) and determine the optimum parameter combination. Thus, an SVR model with strong prediction ability was established. The prediction results of Tartary buckwheat purity by full-spectrum SVR model are shown in Table 3. The R2p of the full-spectrum SVR model established by the three parameter-optimization methods combined with different preprocessing methods was found to exceed 0.96. Among them, the prediction result of the SVR model established by SNV, MSC, MMN, and SNV-DT was better than that of the SVR model established by the raw spectrum, and even better than the PLSR model in the adulteration identification analysis of Sichuan and Shanxi Tartary buckwheat. For the full-spectrum CV-SVR model, the R2p of the MSC preprocessing model was higher, but the kernel parameter g was 1024, which was prone to overfitting and poor generalization ability (Tu et al., 2015). In the adulteration analysis of Tartary buckwheat in Inner Mongolia, the prediction accuracy of MSC-GA-SVR model was higher, i.e., R2p was 0.9985 and RMSEP was 0.0002. In Sichuan Tartary buckwheat adulteration analysis, the prediction accuracy of SNV-DT-CV-SVR model was higher, i.e., R2p was 0.9957 and RMSEP was 0.0004. In Shanxi Tartary buckwheat adulteration analysis, the prediction accuracy of MMN-PSO-SVR model was higher, i.e., R2p was 0.9982 and RMSEP was 0.0002. These results showed that the three parameter-optimization algorithms were feasible to establish the prediction model for SVR.

Table 3.

Prediction results of SVR models under different preprocessing of Tartary buckwheat from Inner Mongolia, Sichuan and Shanxi.

| Modeling method | Preprocessing methods | Number of variables | Inner Mongolia |

Sichuan |

Shanxi |

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters |

Calibration set |

Prediction set |

Parameters |

Calibration set |

Prediction set |

Parameters |

Calibration set |

Prediction set |

||||||||||||

| C | g | R2c | RMSEC | R2p | RMSEP | C | g | R2c | RMSEC | R2p | RMSEP | C | g | R2c | RMSEC | R2p | RMSEP | |||

| CV-SVR |

RAW | 256 | 128 | 36.7583 | 0.9993 | 0.0001 | 0.9970 | 0.0003 | 776.0469 | 4.5948 | 0.9895 | 0.0012 | 0.9827 | 0.0016 | 48.5029 | 73.5167 | 0.9980 | 0.0002 | 0.9958 | 0.0005 |

| SNV | 256 | 8 | 55.7152 | 0.9993 | 0.0001 | 0.9982 | 0.0003 | 6.0629 | 42.2243 | 0.9991 | 0.0001 | 0.9949 | 0.0006 | 0.1436 | 42.2243 | 0.9960 | 0.0004 | 0.9960 | 0.0006 | |

| MSC | 256 | 36.7583 | 1024 | 0.9993 | 0.0001 | 0.9983 | 0.0002 | 48.5029 | 1024 | 0.9977 | 0.0002 | 0.9905 | 0.0011 | 0.6598 | 1024 | 0.9951 | 0.0005 | 0.9964 | 0.0005 | |

| MMN | 256 | 6.9644 | 168.8970 | 0.9993 | 0.0001 | 0.9983 | 0.0002 | 1.5157 | 168.8970 | 0.9946 | 0.0005 | 0.9939 | 0.0007 | 0.1895 | 194.0117 | 0.9960 | 0.0004 | 0.9974 | 0.0003 | |

| SG | 256 | 111.4305 | 84.4485 | 0.9993 | 0.0001 | 0.9971 | 0.0003 | 337.7940 | 10.5561 | 0.9880 | 0.0013 | 0.9820 | 0.0018 | 48.5029 | 73.5167 | 0.9967 | 0.0003 | 0.9964 | 0.0004 | |

| SG-1st | 256 | 3.4822 | 1024 | 0.9963 | 0.0004 | 0.9967 | 0.0004 | 675.5881 | 1024 | 0.9905 | 0.001 | 0.9805 | 0.0018 | 64 | 1024 | 0.9946 | 0.0005 | 0.9825 | 0.0031 | |

|

SNV-DT |

256 |

4.5948 |

147.0334 |

0.9993 |

0.0001 |

0.9969 |

0.0005 |

2.6390 |

64 |

0.9991 |

0.0001 |

0.9957 |

0.0004 |

0.1250 |

64 |

0.9960 |

0.0004 |

0.9926 |

0.0011 |

|

| GA-SVR |

RAW | 256 | 64.1679 | 0.0649 | 0.9683 | 0.0034 | 0.9847 | 0.0017 | 94.9643 | 0.3252 | 0.9578 | 0.0046 | 0.9691 | 0.0029 | 62.5853 | 0.3233 | 0.9867 | 0.0014 | 0.9937 | 0.0007 |

| SNV | 256 | 0.4503 | 4.1247 | 0.9972 | 0.0003 | 0.9982 | 0.0002 | 41.7828 | 0.0620 | 0.9778 | 0.0022 | 0.9796 | 0.0026 | 4.7297 | 10.9282 | 0.9986 | 0.0001 | 0.9979 | 0.0003 | |

| MSC | 256 | 7.7540 | 471.3669 | 0.9990 | 0.0001 | 0.9985 | 0.0002 | 76.8093 | 5.9071 | 0.9782 | 0.0022 | 0.9801 | 0.0025 | 51.3329 | 1000 | 0.9992 | 0.0001 | 0.9973 | 0.0003 | |

| MMN | 256 | 15.9755 | 128.4962 | 0.9993 | 0.0001 | 0.9983 | 0.0002 | 80.8023 | 0.2985 | 0.9788 | 0.0022 | 0.9809 | 0.002 | 26.1010 | 76.8977 | 0.9992 | 0.0001 | 0.9982 | 0.0003 | |

| SG | 256 | 63.6873 | 0.0592 | 0.9642 | 0.0039 | 0.9828 | 0.019 | 87.6362 | 0.4330 | 0.9560 | 0.0048 | 0.9671 | 0.0032 | 28.1486 | 0.7420 | 0.9860 | 0.0015 | 0.9931 | 0.0008 | |

| SG-1st | 256 | 82.8784 | 32.5375 | 0.9944 | 0.0006 | 0.9956 | 0.0005 | 75.0867 | 273.8486 | 0.9762 | 0.0024 | 0.9634 | 0.0045 | 18.6157 | 496.9807 | 0.9929 | 0.0007 | 0.9863 | 0.0031 | |

|

SNV-DT |

256 |

32.4694 |

3.8949 |

0.9993 |

0.0001 |

0.9981 |

0.0002 |

74.5807 |

0.0430 |

0.9785 |

0.0022 |

0.9757 |

0.003 |

0.9395 |

12.0984 |

0.9971 |

0.0003 |

0.9982 |

0.0002 |

|

| PSO-SVR | RAW | 256 | 14.7129 | 0.1834 | 0.9603 | 0.0043 | 0.9799 | 0.0022 | 28.3583 | 1.1515 | 0.9597 | 0.0044 | 0.9701 | 0.0028 | 22.1067 | 1.0983 | 0.9874 | 0.0013 | 0.9939 | 0.0007 |

| SNV | 256 | 22.6567 | 3.6196 | 0.9993 | 0.0001 | 0.9984 | 0.0002 | 12.4957 | 0.2170 | 0.9783 | 0.0022 | 0.9819 | 0.0023 | 3.0771 | 10.6916 | 0.9983 | 0.0002 | 0.9980 | 0.0003 | |

| MSC | 256 | 5.3255 | 470.7442 | 0.9988 | 0.0001 | 0.9985 | 0.0002 | 55.3193 | 9.4121 | 0.9789 | 0.0021 | 0.9813 | 0.0023 | 10.0883 | 1000 | 0.9986 | 0.0001 | 0.9978 | 0.0003 | |

| MMN | 256 | 12.0768 | 118.8129 | 0.9993 | 0.0001 | 0.9983 | 0.0001 | 16.7824 | 1.5821 | 0.9796 | 0.0021 | 0.9836 | 0.0018 | 11.1221 | 77.1472 | 0.9992 | 0.0001 | 0.9982 | 0.0002 | |

| SG | 256 | 12.4957 | 0.217 | 0.9600 | 0.0043 | 0.9793 | 0.0022 | 21.7417 | 1.6115 | 0.9558 | 0.0049 | 0.9675 | 0.0031 | 29.2601 | 1.084 | 0.9871 | 0.0014 | 0.9935 | 0.0007 | |

| SG-1st | 256 | 69.6259 | 44.2865 | 0.9949 | 0.0006 | 0.9959 | 0.0005 | 73.3634 | 279.5391 | 0.9762 | 0.0024 | 0.9634 | 0.0045 | 34.6422 | 264.9562 | 0.9929 | 0.0007 | 0.9864 | 0.0031 | |

| SNV-DT | 256 | 14.0111 | 3.9591 | 0.9992 | 0.0001 | 0.9982 | 0.0002 | 10.6049 | 0.3308 | 0.9793 | 0.0021 | 0.9804 | 0.0025 | 21.6685 | 11.4546 | 0.9992 | 0.0001 | 0.9979 | 0.0003 | |

3.3.2. Non-full-spectrum SVR model

To eliminate the redundant variables in the NIRS and improve the stability and accuracy of the SVR prediction model, the CARS algorithm was used to simplify the model. Fig. 3 shows the process of CARS optimization of Shanxi Tartary buckwheat after SNV-DT preprocessing. In the CARS algorithm, the number of Monte Carlo sampling runs was set to 100 times, and the wavelength variable corresponding with the minimum root-mean-square error of cross-validation (RMSECV) model was selected by five-fold cross validation. Fig. 3(a) shows the relationship between the number of Monte Carlo sampling times and the number of sampling variables. In the first five times of sampling, the number of sampling variables decreased rapidly, which reflected mostly the process of eliminating non-informative variables. After the decrease to a certain extent, it tended to be flat. Fig. 3(b) shows that when the number of sampling times reached 13, the corresponding RMSECV was at least 0.02711. Fig. 3(c) shows that the variable coefficients changed with different sampling times. “*" was used in the figure to describe the optimum feature wavelength corresponding with the minimum RMSECV. Fig. 3(d) shows the variable distribution map obtained by screening. The number of feature variables was reduced from 256 to 51, which effectively eliminated the redundant variables in the spectrum.

Fig. 3.

CARS variable-selection optimization process: (a) changes in the number of selected variables, (b) changes in RMSECV, (c) regression coefficients of each variable during the calculations of CARS algorithm, and (d) distribution of selected feature variables by CARS.

The CARS algorithm was used to screen the characteristics of the other two kinds of Tartary buckwheat samples under preprocessing. The prediction results of adulteration degree of non-full-spectrum SVR model are shown in Table 4. For Tartary buckwheat samples from Inner Mongolia and Sichuan province, the overall effect of the model established using CARS screening was poor and not as good as the full-spectrum SVR model. This finding may be due to the absence of effective information or insufficient extraction of effective information in the process of feature-wavelength screening, resulting in poor modeling effect (Tu et al., 2015). For Tartary buckwheat sample from Shanxi, the prediction performance of the model established by SNV-DT preprocessing was the optimum and better than that of the full-spectrum model. The R2p of SNV-DT-CARS-PSO-SVR model reached 0.9987, and the parameter value was (10.0567, 48.8665). On the premise of ensuring the prediction accuracy of the model, the CARS algorithm improved the generalization ability and modeling efficiency of the model, and the effect of the effective information extraction of spectral data was relatively ideal.

Table 4.

Prediction results of SVR models of Tartary buckwheat from Inner Mongolia, Sichuan and Shanxi under different preprocessing after CARS screening.

| Modeling methods | Preprocessing methods | Inner Mongolia |

Sichuan |

Shanxi |

||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of variables | Parameters |

Calibration set |

Prediction set |

Number of variables | Parameters |

Calibration set |

Prediction set |

Number of variables | Parameters |

Calibration set |

Prediction set |

|||||||||||

| C | g | R2c | RMSEC | R2p | RMSEP | C | g | R2c | RMSEC | R2p | RMSEP | C | g | R2c | RMSEC | R2p | RMSEP | |||||

| CV-SVR |

RAW | 26 | 445.7219 | 256 | 0.9987 | 0.0001 | 0.9972 | 0.0003 | 35 | 294.0668 | 128 | 0.9887 | 0.0012 | 0.9734 | 0.0025 | 39 | 194.0117 | 675.5881 | 0.9984 | 0.0002 | 0.9938 | 0.0007 |

| SNV | 35 | 3.4822 | 891.4438 | 0.9993 | 0.0001 | 0.9981 | 0.0002 | 37 | 1.3195 | 388.0234 | 0.9943 | 0.0006 | 0.9917 | 0.0009 | 39 | 0.0947 | 588.1336 | 0.9953 | 0.0005 | 0.9867 | 0.0025 | |

| MSC | 29 | 111.4305 | 1024 | 0.9980 | 0.0002 | 0.9982 | 0.0002 | 35 | 55.7152 | 1024 | 0.9851 | 0.0015 | 0.9879 | 0.0015 | 39 | 6.9644 | 1024 | 0.9941 | 0.0006 | 0.9960 | 0.0006 | |

| MMN | 32 | 13.9288 | 891.4438 | 0.9989 | 0.0001 | 0.9980 | 0.0002 | 35 | 3.0314 | 1024 | 0.9910 | 0.0009 | 0.9922 | 0.0008 | 35 | 0.1649 | 1024 | 0.9949 | 0.0005 | 0.9971 | 0.0004 | |

| SG | 32 | 776.0469 | 222.8609 | 0.9991 | 0.0001 | 0.9611 | 0.0092 | 39 | 337.7940 | 64 | 0.9874 | 0.0014 | 0.9807 | 0.0019 | 29 | 55.7152 | 675.5881 | 0.9962 | 0.0004 | 0.9963 | 0.0004 | |

| SG-1st | 44 | 776.0469 | 1024 | 0.9973 | 0.0003 | 0.9978 | 0.0072 | 47 | 1024 | 1024 | 0.9815 | 0.0019 | 0.9646 | 0.0034 | 255 | 1024 | 1024 | 0.9933 | 0.0007 | 0.9871 | 0.0017 | |

| SG-2nd | 34 | 1024 | 1024 | 0.9923 | 0.0008 | 0.9907 | 0.001 | 54 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0 | 0.0986 | 0 | 0.1634 | 51 | 1024 | 1024 | 0.9865 | 0.0014 | 0.9844 | 0.0025 | |

|

SNV-DT |

41 |

5.278 |

512 |

0.9993 |

0.0001 |

0.9975 |

0.0002 |

55 |

6.0629 |

55.7152 |

0.9904 |

0.001 |

0.9932 |

0.0008 |

51 |

0.2176 |

776.0469 |

0.9981 |

0.0002 |

0.9973 |

0.0003 |

|

| GA-SVR |

RAW | 26 | 99.0023 | 0.5494 | 0.9825 | 0.0019 | 0.992 | 0.0009 | 35 | 67.6401 | 3.9387 | 0.9582 | 0.0046 | 0.9679 | 0.003 | 39 | 74.1291 | 1.4134 | 0.9861 | 0.0015 | 0.9931 | 0.0008 |

| SNV | 35 | 23.6285 | 170.1336 | 0.9992 | 0.0001 | 0.9978 | 0.0002 | 37 | 38.1195 | 0.5332 | 0.9813 | 0.0019 | 0.9816 | 0.0023 | 39 | 0.0948 | 40.4282 | 0.9912 | 0.0009 | 0.9930 | 0.0013 | |

| MSC | 29 | 5.2268 | 211.3114 | 0.9970 | 0.0003 | 0.9976 | 0.0003 | 35 | 69.1133 | 52.9404 | 0.9813 | 0.0019 | 0.9817 | 0.0023 | 39 | 23.6267 | 999.9924 | 0.9946 | 0.0005 | 0.9964 | 0.0005 | |

| MMN | 32 | 44.7944 | 969.4309 | 0.9992 | 0.0001 | 0.9977 | 0.0002 | 35 | 18.4855 | 6.8551 | 0.9781 | 0.0022 | 0.9769 | 0.0029 | 35 | 16.4793 | 436.5378 | 0.9976 | 0.0002 | 0.9984 | 0.0002 | |

| SG | 32 | 79.6892 | 0.4616 | 0.9775 | 0.0024 | 0.9892 | 0.0013 | 39 | 82.7218 | 2.7132 | 0.9588 | 0.0045 | 0.9676 | 0.0031 | 29 | 55.8240 | 2.4634 | 0.9858 | 0.0015 | 0.9931 | 0.0008 | |

| SG-1st | 44 | 91.5884 | 310.8626 | 0.9962 | 0.0004 | 0.9972 | 0.0097 | 47 | 99.7173 | 858.0904 | 0.9747 | 0.0026 | 0.9518 | 0.0061 | 255 | 87.5227 | 515.6899 | 0.9929 | 0.0007 | 0.9892 | 0.0015 | |

| SG-2nd | 34 | 99.5260 | 995.9393 | 0.9895 | 0.0011 | 0.9909 | 0.001 | 54 | 99.6802 | 998.6448 | 0.9446 | 0.0059 | 0.6128 | 0.0548 | 51 | 99.8743 | 996.2616 | 0.9793 | 0.0022 | 0.9610 | 0.0096 | |

|

SNV-DT |

41 |

71.9222 |

0.105 |

0.9969 |

0.0003 |

0.9970 |

0.0003 |

55 |

63.0586 |

0.2518 |

0.9791 |

0.0021 |

0.9760 |

0.0031 |

51 |

79.5164 |

48.8940 |

0.9987 |

0.0001 |

0.9981 |

0.0003 |

|

| PSO-SVR | RAW | 26 | 22.3709 | 3.1012 | 0.9885 | 0.0013 | 0.9942 | 0.0006 | 35 | 48.0679 | 5.4254 | 0.9581 | 0.0046 | 0.9679 | 0.003 | 39 | 58.8203 | 2.3974 | 0.9869 | 0.0014 | 0.9934 | 0.0007 |

| SNV | 35 | 2.8113 | 102.0651 | 0.9985 | 0.0002 | 0.9983 | 0.0002 | 37 | 9.9052 | 1.7547 | 0.9808 | 0.0019 | 0.9814 | 0.0024 | 39 | 9.5623 | 40.6473 | 0.9971 | 0.0003 | 0.9986 | 0.0002 | |

| MSC | 29 | 15.8356 | 210.1449 | 0.9975 | 0.0003 | 0.9978 | 0.0002 | 35 | 39.7044 | 83.7515 | 0.9811 | 0.0019 | 0.9813 | 0.0023 | 39 | 15.5483 | 1000 | 0.9945 | 0.0005 | 0.9962 | 0.0005 | |

| MMN | 32 | 21.7638 | 954.3434 | 0.999 | 0.0001 | 0.9980 | 0.0002 | 35 | 21.4624 | 8.4421 | 0.9801 | 0.002 | 0.9808 | 0.0023 | 35 | 14.4740 | 436.6765 | 0.9975 | 0.0002 | 0.9984 | 0.0002 | |

| SG | 32 | 17.7000 | 2.1661 | 0.9812 | 0.002 | 0.9899 | 0.0012 | 39 | 22.4437 | 9.6709 | 0.9598 | 0.0044 | 0.9683 | 0.003 | 29 | 63.0797 | 2.2894 | 0.9859 | 0.0015 | 0.9932 | 0.0008 | |

| SG-1st | 44 | 86.5797 | 346.9178 | 0.9962 | 0.0004 | 0.9972 | 0.0102 | 47 | 97.2623 | 1000 | 0.9753 | 0.0025 | 0.9509 | 0.0062 | 255 | 77.0715 | 579.9529 | 0.9929 | 0.0007 | 0.9892 | 0.0015 | |

| SG-2nd | 34 | 99.4144 | 1000 | 0.9895 | 0.0011 | 0.9909 | 0.001 | 54 | 100 | 999.6203 | 0.9446 | 0.0059 | 0.6130 | 0.0547 | 51 | 100 | 1000 | 0.9793 | 0.0022 | 0.9610 | 0.0096 | |

| SNV-DT | 41 | 32.1123 | 0.8504 | 0.9976 | 0.0003 | 0.9975 | 0.0003 | 55 | 17.5431 | 1.0815 | 0.9802 | 0.002 | 0.9811 | 0.0025 | 51 | 10.0567 | 48.8665 | 0.9977 | 0.0002 | 0.9987 | 0.0002 | |

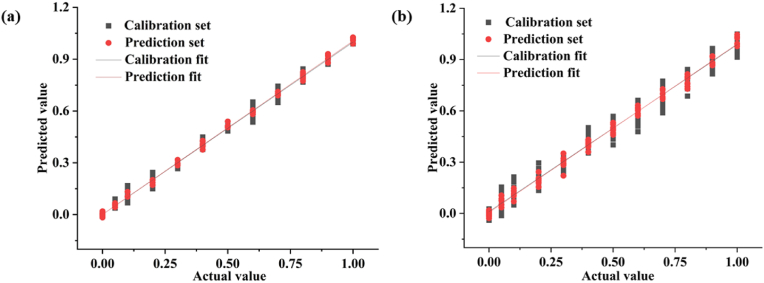

Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 showed that the prediction accuracy of SG-1st-PLSR model was the highest in the adulteration identification of Tartary buckwheat in Inner Mongolia, with a correlation coefficient R2p of 0.9991 and RMSEP of 0.014. In the adulteration identification of Tartary buckwheat in Sichuan, the prediction accuracy of SNV-DT-CV-SVR model was the highest, with an R2p of 0.9957 and RMSEP of 0.0004. The SNV-DT-CARS-PSO-SVR model had the optimum prediction performance in the adulteration identification of Tartary buckwheat in Shanxi with an R2p of 0.9987 and RMSEP of 0.0002.

A linear-fitting diagram of predicted and true values was prepared for the optimum discrimination models of the three samples, as shown in Fig. 4 and S5. Fig. 4(a) showed the linear-fitting diagram of the predicted and actual values of the SNV-DT-CARS-PSO-SVR model of Shanxi Tartary buckwheat. The slope of the fitting line was close to 1, and the R2p reached 0.9987, indicating a high degree of fitting, which meant that the model had a high potential for adulteration detection. For convenient comparison, Fig. 4(b) showed the linear-fitting diagram of predicted and actual values of Tartary buckwheat in Shanxi based on the full-spectrum raw spectral PSO-SVR model. Compared with Fig. 4(a), the data points on the line were looser, especially the points related to the prediction set. Under the same modeling algorithm, the variable-selection model based on the CARS was superior to the full-spectrum model. Consistent with the results of previous studies, a quality identification model of Cabernet Sauvignon grape with NIRS and CARS-SVR has supported the optimum prediction performance (Luo et al., 2021). It was verified that the CARS-SVR model was an effective method to detect the adulterated concentration of Panax notoginseng flour (Zhang et al., 2022). CARS-SVR model was also established to realize the rapid detection of water content in lettuce leaves (Sun et al., 2017). Therefore, CARS combined with SVR had great potential applications in the quantitative analysis of food quality.

Fig. 4.

Linear-fitting diagram of Shanxi Tartary buckwheat adulteration identification model: (a) SNV-DT-CARS-PSO-SVR model, and (b) RAW-PSO-SVR model.

The prediction effect of the models separately built by PLSR and SVR algorithms on the adulteration degree of Tartary buckwheat were compared. Results showed that the two algorithms were all suitable for predicting the adulteration degree of Tartary buckwheat. However, the prediction performance of SVR model was better in the adulteration analysis of Tartary buckwheat in Sichuan and Shanxi, and the R2p of the optimum model were above 0.99. This finding was due to the ability of the SVR method to solve the problems of small sample, nonlinear, multiple dimensions, and local minimum well and its good generalization ability. It can maximize the reliability of prediction in the case of small sample and obtain the global optimum solution. PLSR was used to establish correction and prediction models by using the full spectral information of samples, which can also obtain higher correlation coefficients and better prediction results. The model built by PLSR was suitable for the adulteration identification of Tartary buckwheat in Inner Mongolia, but the prediction results of this study were relatively poor in the identification of Tartary buckwheat from Sichuan and Shanxi.

3.4. Performance of preprocessing methods and selection of feature wavelengths

The preprocessing methods and the variable screening methods applied to spectral data affected the model performance, as well as the preprocessing methods. In the analysis of Tartary buckwheat in Inner Mongolia, the R2p of the PLSR model established by using SG-1st algorithm was higher than that by other spectral preprocessing methods, and the RMSEP was smaller. SG-1st preprocessing showed excellent modeling effects in most studies (Rukundo et al., 2020), but poor modeling effects in Sichuan Tartary buckwheat and Shanxi Tartary Buckwheat. Derivation in preprocessing can eliminate the influence of baseline offset and gentle background interference and provide higher resolution. However, it also amplified noise and reduced the signal-to-noise ratio. Additionally, for the adulteration identification of Tartary buckwheat from Sichuan and Shanxi, the R2p of the model constructed by SNV-DT was higher than that of other preprocessing methods, and the RMSEP was also smaller. This finding was due to the ability of SNV-DT to effectively eliminate the drift of the spectral curve caused by the distance difference between the optical fiber probe and the sample, consistent with the experimental results of the previous application of preprocessing methods to improve the model's prediction effect (Yi et al., 2017; Bala et al., 2022).

The selection of feature variables also influenced the model's performance. Studies have shown that CARS can effectively extract feature variables to optimize the model, reduce redundant wavelength variables, and improve modeling efficiency (Chen et al., 2019; Basri et al., 2017; Li et al., 2023). However, in previous research, the modeling constructed under the non-full spectrum was not as good as the full spectrum model (Zhao et al., 2019). The preprocessing may have caused the loss of effective information in the spectral data, or the CARS method may not have completely extracted effective information, resulting in insufficient effective information involved in the final modeling.

4. Conclusions

This study used NIRS combined with chemometrics for the quantitative analysis of adulterated common buckwheat in Tartary buckwheat. By collecting the NIRS information of 12 proportions of adulterated Tartary buckwheat samples, the quantitative analysis model of the adulterated degree of Tartary buckwheat was constructed by PLSR and SVR through seven preprocessing methods, CARS feature-variable screening, and three parameter-optimization algorithms. The constructed SG-1st-PLSR, SNV-DT-CV-SVR and SNV-DT-CARS-PSO-SVR model showed excellent prediction accuracy than other models for the adulteration identification of Tartary buckwheat from Inner Mongolia, Sichaun, and Shanxi, respectively. The results of PLSR and SVR modeling for the prediction of Tartary buckwheat adulteration content were satisfactory, and the correlation coefficients of the optimum identification models all exceeded 0.99, indicating that the model of NIRS to determine Tartary buckwheat adulteration degree presented high accuracy and performance. In conclusion, the quantitative model of Tartary buckwheat adulteration established by NIRS and chemometrics can accurately determine the content of adulterated common buckwheat. These results indicated that the method had strong predictive performance and applicability and can be developed to rapidly detect adulterated cereal products. Indeed, future research should improve the universality and practicality of the identification models for Tartary Buckwheat flour adulteration. It is also highlighted to develop new feasible models for practical applications, as well as the intelligent and portable detector based on NIRS discriminant models.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Yinghui Chai: Data curation, Data collection, Software, Writing – original draft, draft writing and revision. Yue Yu: Methodology, Software, Writing – review & editing, manuscript reviewing, Supervision. Hui Zhu: Data curation, Data collection, Software. Zhanming Li: Supervision, Software, Writing – review & editing, manuscript reviewing. Hao Dong: Software, Writing – review & editing, manuscript reviewing. Hongshun Yang: Software, Writing – review & editing, manuscript reviewing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Postgraduate Research & Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province (SJCX23_2242).

Handling Editor: Dr. Maria Corradini

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crfs.2023.100573.

Contributor Information

Yue Yu, Email: yuyue2020@just.edu.cn.

Zhanming Li, Email: lizhanming@just.edu.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Bala M., Sethi S., Sharma S., Mridula D., Kaur G. Prediction of maize flour adulteration in chickpea flour (besan) using near infrared spectroscopy. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022;59(8):3130–3138. doi: 10.1007/s13197-022-05456-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basri K.N., Hussain M.N., Bakar J., Sharif Z., Khir M.F.A., Zoolfakar A.S. Classification and quantification of palm oil adulteration via portable NIR spectroscopy. Spectrochim. Acta Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2017;173:335–342. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2016.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C., Li H.Y., Lv X.Y., Tang J., Chen C., Zheng X.X. Application of near infrared spectroscopy combined with SVR algorithm in rapid detection of cAMP content in red jujube. Optik. 2019;194 doi: 10.1016/j.ijleo.2019.163063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Lin Z., Tan C. Fast quantitative detection of sesame oil adulteration by near-infrared spectroscopy and chemometric models. Vib. Spectrosc. 2018;99:178–183. doi: 10.1016/j.vibspec.2018.10.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Tan C., Lin Z., Li H. Quantifying several adulterants of notoginseng powder by near-infrared spectroscopy and multivariate calibration. Spectrochim. Acta. 2019;211:280–286. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2018.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dou X.J., Zhang L.X., Yang R.N., Wang X., Yu L., Yue X.F., Ma F., Mao J., Wang X.P., Li P.W. Adulteration detection of essence in sesame oil based on headspace gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry. Food Chem. 2022;370 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.131373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Q.W., Zhu M.T., Shi T., Luo X., Gan B., Tang L.J., Chen Y. Adulteration detection of corn oil, rapeseed oil and sunflower oil in camellia oil by in situ diffuse reflectance near-infrared spectroscopy and chemometrics. Food Control. 2021;121 doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2020.107577. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Firmani P., De Luca S.D., Bucci R., Marini F., Biancolillo A. Near infrared (NIR) spectroscopy-based classification for the authentication of Darjeeling black tea. Food Control. 2019;100:292–299. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2019.02.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gunning Y., Davies K.S., Kemsley E.K. Authentication of saffron using 60 MHz 1H NMR spectroscopy. Food Chem. 2023;404 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.134649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He W.J., Zeng R., Bai Y.L., Cai T.C., Gu Q. The nutritive value and progress in development and utilization of Tartary buckwheat. Farm Products Processing. 2019;23:69–75. [Google Scholar]

- Khamsopha D., Woranitta S., Teerachaichayut S. Utilizing near infrared hyperspectral imaging for quantitatively predicting adulteration in tapioca starch. Food Control. 2021;123 doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2020.107781. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M.J., Park S.B., Kang H.B., Lee Y.M., Gwak Y.S., Kim H.Y. Development and validation of a multiplex real-time PCR assay for accurate authentication of common buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum) and tartary buckwheat (Fagopyrum tataricum) in food. Food Control. 2023;145 doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2022.109442. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leng T., Li F., Chen Y., Tang L.J., Xie J.H., Yu Q. Fast quantification of total volatile basic nitrogen (TVB-N) content in beef and pork by near-infrared spectroscopy: comparison of SVR and PLS model. Meat Sci. 2021;180 doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2021.108559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H.Y., Lv Q.Y., Liu A.K., Wang J.R., Sun X.Q., Deng J., Chen Q.F., Wu Q. Comparative metabolomics study of Tartary (Fagopyrum tataricum (L.) Gaertn) and common (Fagopyrum esculentum Moench) buckwheat seeds. Food Chem. 2022;371 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.131125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H.Y., Lv Q.Y., Ma C., Qu J.T., Cai F., Deng J., Huang J., Ran P., Shi T.X., Chen Q.F. Metabolite profiling and transcriptome analyses provide insights into the flavonoid biosynthesis in the developing seed of tartary buckwheat (Fagopyrum tataricum) J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019;67(40):11262–11276. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.9b03135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.P., Wei Y.X., Li J.C., Liu R.X., Xu S.G., Xiong S.Y., Guo Y., Qiao X.L., Wang S.W. A novel duplex SYBR green real-time PCR with melting curve analysis method for beef adulteration detection. Food Chem. 2021;338 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.127932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S.L., Xing B.C., Lin D., Yi H.J., Shao Q.S. Rapid detection of saffron (Crocus sativus L.) Adulterated with lotus stamens and corn stigmas by near-infrared spectroscopy and chemometrics. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2020;152 doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2020.112539. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z.M., Song J.H., Ma Y.X., Yu Y., He X.M., Guo Y.X., Dou J.X., Dong H. Identification of aged-rice adulteration based on near-infrared spectroscopy combined with partial least squares regression and characteristic wavelength variables. Food Chem. X. 2023;17 doi: 10.1016/j.fochx.2022.100539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima A.B.S.D., Batista A.S., Jesus J.C.D., Silva J.D.J., Araújo A.C.M.D., Santos L.S. Fast quantitative detection of black pepper and cumin adulterations by near-infrared spectroscopy and multivariate modeling. Food Control. 2020;107 doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2019.106802. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu P., Wang J., Li Q., Gao J., Tan X.Y., Bian X.H. Rapid identification and quantification of Panax notoginseng with its adulterants by near infrared spectroscopy combined with chemometrics. Spectrochim. Acta. 2019;206:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2018.07.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y.J., Dong J., Shi X.W., Wang W.X., Li Z.M., Sun J.T. Quantitative detection of soluble solids content, pH, and total phenol in Cabernet Sauvignon grapes based on near infrared spectroscopy. Int. J. Food Eng. 2021;17(5):365–375. [Google Scholar]

- Mahgoub Y.A., Shawky E., Darwish F.A., El Sebakhy N.A., El-Hawiet A.M. Near-infrared spectroscopy combined with chemometrics for quality control of German chamomile (Matricaria recutita L.) and detection of its adulteration by related toxic plants. Microchem. J. 2020;158 doi: 10.1016/j.microc.2020.105153. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park B., Seo Y., Yoon S.C., Hinton A.J., Windham W.R., Lawrence K.C. Hyperspectral microscope imaging methods to classify gram-positive and gram-negative foodborne pathogenic bacteria. T ASABE. 2015;58(1):5–16. doi: 10.13031/TRANS.58.10832. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Popa S., Milea M.S., Boran S., Nițu S.V., Moșoarcă G.E., Vancea C., Lazău R.I. Rapid adulteration detection of cold pressed oils with their refined versions by UV–Vis spectroscopy. Sci REP-UK. 2020;10(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-72558-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rismiwandira K., Roosmayanti F., Pahlawan M.F.R., Masithoh R.E. Application of Fourier Transform Near-Infrared (FT-NIR) spectroscopy for detection of adulteration in palm sugar. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021;653(1) [Google Scholar]

- Rukundo I.R., Danao M., Weller C.L., Wehling R.L., Eskridge K.M. Use of a handheld near infrared spectrometer and partial least squares regression to quantify metanil yellow adulteration in turmeric powder. J. Near Infrared Spectrosc. 2020;28(2):81–92. doi: 10.1177/0967033519898889. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Santos P.M., Pereira-Filho E.R., Colnago L.A. Detection and quantification of milk adulteration using time domain nuclear magnetic resonance (TD-NMR) Microchem. J. 2016;124:15–19. doi: 10.1016/j.microc.2015.07.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J., Tong G.Q., Yang Q., Huang M.Q., Ye H., Liu Y.C., Wu J.H., Zahng J.L., Sun X.T., Zhao D.R. Characterization of key aroma compounds in tartary buckwheat (fagopyrum tataricum Gaertn.) by means of sensory-directed flavor analysis [J] J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021;69(38):11361–11371. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.1c03708. 2021, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J., Cong S.L., Mao H.P., Wu X.H., Zhang X.D., Wang P. CARS-ABC-SVR model for predicting leaf moisture of leaf-used lettuce based on hyperspectral. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2017;33(5):178–184. doi: 10.11975/j.issn.1002-6819.2017.05.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X.F., Li H.L., Yi Y., Hua H., Guan Y., Chen C. Rapid detection and quantification of adulteration in Chinese hawthorn fruits powder by near-infrared spectroscopy combined with chemometrics. Spectrochim. Acta. 2021;250 doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2020.119346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y.T., Ding S.F., Zhang Z.C., Jia W.K. An improved grid search algorithm to optimize SVR for prediction. Soft Comput. 2021;25:5633–5644. [Google Scholar]

- Tu B., Song Z.Q., Zheng X., Zeng L.L., Yi C., He D.P., Qi P.S. Qualitative-quantitative analysis of rice bran oil adulteration based on laser near infrared spectroscopy. Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 2015;35:1539–1545. (06) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J.F., Wang J.X., Zuo X., Huang Y.F., Teng Y., Zhang S.S., Liu Y. Adulteration detection of buckwheat powder by clustering analysis of flavonoid components. Sci Technol Food Ind. 2016;37(13):309–314. [Google Scholar]

- Wang L.J., Hui Y., Jiang K., Yin G., Wang J., Yan Y., Wang Y., Li J., Wang P., Bi K.S., Wang T.J. Potential of near infrared spectroscopy and pattern recognition for rapid discrimination and quantification of Gleditsia sinensis thorn powder with adulterants [J] J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2018;160:64–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2018.07.036. 2018, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Wu Q., Kamruzzaman M. Portable NIR spectroscopy and PLS based variable selection for adulteration detection in quinoa flour. Food Control. 2022;138 doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2022.108970. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X.Y., Zhu S.P., Huang H., Xu D. Quantitative identification of adulterated Sichuan pepper powder by near-infrared spectroscopy coupled with chemometrics. J. Food Qual. 2017:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2017/5019816. 2017: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yan H., Song X., Tian K., Gao J., Li Q., Xiong Y., Min S. A modification of the bootstrapping soft shrinkage approach for spectral variable selection in the issue of over-fitting, model accuracy and variable selection credibility. Spectrochim. Acta. 2019;210:362–371. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2018.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi J.H., Sun Y.F., Zhu Z.B., Liu N., Lu J.L. Near-infrared reflectance spectroscopy for the prediction of chemical composition in walnut kernel. Int. J. Food Prop. 2017;20:1633–1642. doi: 10.1080/10942912.2016.1217006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F.J., Shi L., Li L.X., Zhou Y.F., Tian L.Q., Cui X.M., Gao Y.P. Nondestructive detection for adulteration of panax notoginseng powder based on hyperspectral imaging combined with arithmetic optimization algorithm‐support vector regression. J. Food Process. Eng. 2022;45 doi: 10.1111/jfpe.14096. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Schultz M.A., Cash R., Barrett D.M., Mccarthy M.J. Determination of quality parameters of tomato paste using guided microwave spectroscopy. Food Control. 2014;40:214–223. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2013.12.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H.T., Feng Y.Z., Chen W., Jia G.F. Application of invasive weed optimization and least square support vector machine for prediction of beef adulteration with spoiled beef based on visible near-infrared (Vis-NIR) hyperspectral imaging. Meat Sci. 2019;151:75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2019.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou D.R., Yu Y., Hu R.W., Li Z.M. Discrimination of Tetrastigma hemsleyanum according to geographical origin by near-infrared spectroscopy combined with a deep learning approach. Spectrochim. Acta Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2020;238 doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2020.118380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou K.P., Liu S.S., Cui J., Zhang H.N., Bi W.H., Tang W. Detection of chemical oxygen demand (COD) of water quality based on fluorescence emission spectra. Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 2020;40(4):1143–1148. doi: 10.3964/j.issn.1000-0593(2019)03-0813-05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo X., Huang Y.F., Yang Z.M., Li B., Peng L.X., Liu Y. Application of UV similarity in buckwheat powder adulteration [J] The Food Industry. 2014;35(2):92–94. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.