Abstract

The development of molecular biology and bioinformatics using next-generation sequencing has dramatically advanced the identification of molecules involved in various diseases and the elucidation of their pathogenesis. Consequently, many molecular-targeted therapies have been developed in the medical field. In veterinary medicine, the world’s first molecular-targeted drug for animals, masitinib, was approved in 2008, followed by the multikinase inhibitor toceranib in 2009. Toceranib was originally approved for mast cell tumors in dogs but has also been shown to be effective in other tumors because of its ability to inhibit molecules involved in angiogenesis. Thus, toceranib has achieved great success as a molecular-targeted cancer therapy for dogs. Although there has been no progress in the development and commercialization of new molecular-targeted drugs for the treatment of cancer since the success of toceranib, several clinical trials have recently reported the administration of novel agents in the research stage to dogs with tumors. This review provides an overview of molecular-targeted drugs for canine tumors, particularly transitional cell carcinomas, and presents some of our recent data.

Keywords: canine, clinical trial, molecular-targeted drug, translational research

In the 1890s, Paul Ehrlich first proposed the scientific concept of targeted therapy as a “magic bullet”, hypothesizing that it might be possible to kill specific targets without toxic effects on the body [45]. Although this theory was initially applied to infectious diseases and not to cancer therapy due to insufficient knowledge of the molecular biology of cancer, the concept has since been extended to molecular-targeted cancer therapy. In human medicine, the earliest molecular-targeted drugs approved for cancer treatment were trastuzumab, an anti-human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) monoclonal antibody approved in 1998 for the treatment of HER2-positive breast cancer, and imatinib, a small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor targeting the breakpoint cluster region-Abelson (BCR-ABL) approved in 2001 for Philadelphia chromosome-positive chronic myelogenous leukemia [1]. The clinical success of these agents provided a paradigm for the widespread use of molecular-targeted drugs in cancer therapy, and a number of molecular-targeted anticancer therapies have since been approved for clinical use in cancer patients.

Molecular-targeted drugs are defined as drugs that target specific proteins (molecules) and inhibit their functions [2]. Broadly, the term “molecular-targeted drug” includes both small-molecule compounds and antibody drugs. Small-molecule drugs target all proteins on the cell surface, in the cytoplasm, and in the nucleus, whereas antibody drugs target proteins expressed on the cell surface (antibodies are macromolecules and cannot pass through the cell membrane). Most small-molecule drugs are oral and can be administered daily, whereas protein-based antibody drugs are digested and cannot be administered orally; therefore, they are administered by intravenous injection. The specificity of antibody drugs to their target molecules is very high, and they rarely cross-react with molecules other than the target. However, the specificity of small-molecule drugs is generally low, and they often cross-react with other molecules that are structurally similar to the target. For example, imatinib, a molecular targeting agent for KIT, was originally developed as a drug that binds to an abnormal protein called BCR-ABL. Multikinase inhibitors, such as toceranib, are designed to target multiple molecules involved in tumor progression by exploiting their low specificity for the target molecule. Small-molecule drugs can be produced inexpensively by chemical synthesis and therefore have low production costs, whereas antibody drugs, which are protein preparations, have high production costs. In veterinary medicine, the term “molecular-targeted drugs” often refers only to small-molecule compounds owing to the limited availability of opportunities to utilize antibody drugs. Hence, this review mainly describes small-molecule compounds as molecular-targeted drugs.

Most small-molecule compounds are designed to target proteins called kinases [19]. Kinases are a general term for an enzyme that transfers the phosphate group of ATP to a substrate protein. Small-molecule compounds exert their inhibitory effects on kinases by competitively binding to the ATP-binding site of the kinase, called the “ATP pocket”, but their specificity is not high, as mentioned above. Thus, many small-molecule compounds exhibit inhibitory effects against multiple kinases. Targeted kinases are classified into tyrosine kinases, serine/threonine kinases, histidine kinases, and aspartate/glutamate kinases, based on the type of amino acid residue of the substrate undergoing phosphorylation. Most small-molecule compounds are tyrosine kinase inhibitors, particularly those targeting receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs). Representative RTKs include KIT, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR), platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR), epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), and HER2. RTKs form dimers upon ligand binding and are activated by the phosphorylation of tyrosine residues on the receptor. Activated RTKs activate intracellular signaling molecules (non-receptor-type kinases) through phosphorylation. Activated intracellular non-receptor-type kinases then sequentially phosphorylate the next set of signaling molecules, and finally, the phosphorylated signaling molecules migrate into the nucleus, where gene transcription is induced and proteins are produced to carry out their functions. V-raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B1 (BRAF), a component of the MAP kinase pathway, is a well-known non-receptor kinase in veterinary oncology and is discussed in more detail in the “BRAF inhibitor” section below.

THE SECOND ERA OF MOLECULAR-TARGETED DRUGS IN VETERINARY MEDICINE

Figure 1A shows the number of articles found by searching “veterinary/molecular-targeted drug/clinical trial” in PubMed by year. The number of papers on clinical trials of molecular-targeted drugs in dogs and cats, rather than in cell lines or cancer-bearing mouse models, shows an interesting trend: there were zero to a few papers in the 1990s and the early 2000s, and the number of papers gradually increased around 2009. This may be related to the approval of masitinib, the world’s first molecular-targeted veterinary drug, in 2008, and toceranib in 2009 in Europe and the United States. Subsequently, the Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor oclacitinib was approved for the treatment of canine atopic dermatitis in 2013, the anti-canine interleukin-31 (IL-31) antibody lokivetmab for the treatment of canine atopic dermatitis in 2016, the prostaglandin E2 receptor 4 (EP4) inhibitor grapiprant for osteoarthritis in 2016, and the anti-canine nerve growth factor (NGF) antibody bedinvetmab and the anti-feline NGF antibody frunevetmab for osteoarthritis in 2020 and 2022, respectively (Fig. 1A). Undoubtedly, the epoch of molecular-targeted therapeutics has dawned upon veterinary medicine, just as it has in the field of human medicine. Unfortunately, approval and clinical application of new molecular-targeted drugs for oncologic diseases have not been achieved since the approval of toceranib. In the opinion of the author, the impact of toceranib on cancer treatment in veterinary medicine has been so substantial that it may have impeded the development of a subsequent drug, as it has satisfactorily fulfilled a certain requirement, which may have delayed the development of a follow-up drug to toceranib. The author defines the period before 2008, when toceranib was introduced, as “before toceranib” and the period after 2009 as “after toceranib (the era of molecular-targeted therapies)” (Fig. 1B). In the post-2009 era of molecular-targeted therapeutics, two peaks were noted in 2011 and 2021. During the first five years after the introduction of toceranib (2009–2013), clinical trials of toceranib were conducted in mast cell tumors and other tumors; however, around 2015, several clinical trials of novel agents targeting entirely new molecules commenced. Although most clinical trials are still pilot studies, there is great potential for new molecular-targeted drugs that will play a role in the next generation of cancer treatment. The author proposes to divide the era of molecular-targeted therapeutics in veterinary medicine into two peaks, the first and second eras, with the year around 2014 as the dividing line (Fig. 1B). The first era of molecular-targeted therapeutics is the era of toceranib, and the second era is the true era after toceranib.

Fig. 1.

The number of articles found by searching “veterinary/molecular-targeted drug/clinical trial” in PubMed by year. (A) Novel molecular-targeted drugs approved in dogs and cats in the last 15 years. (B) The author’s definition of the first and second eras of molecular-targeted therapeutics in veterinary medicine.

TOPICS IN NOVEL MOLECULAR-TARGETED DRUGS FOR CANINE TUMORS

As mentioned in the previous section, the author believes that the era of second-generation molecular-targeted therapeutics has arrived in veterinary medicine. Evidently, clinical trial results of the next generation of molecular-targeted drugs administered to dogs with malignant tumors have been reported over the past decade. Table 1 summarizes research papers on novel molecular-targeted drugs for canine tumors, including preliminary studies [5, 7, 9, 11,12,13,14, 20, 22, 23, 26, 29, 30, 33, 37, 38, 43]. The most notable of these are antibody drugs targeting immune checkpoint molecules [13, 29, 30], which are a group of molecules that suppress immune responses against self and excessive inflammation, such as programmed cell death 1 (PD-1), programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1), and cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) [46]. They play an important role in maintaining homeostasis by suppressing or eliminating T cells that respond to self-antigens and converging immune responses; however, they are also used by tumor cells to evade immune attack. Antibody drugs that inhibit the binding of immune checkpoint molecules are innovative therapeutic agents against various human tumors. The world’s first canine clinical trial of immune checkpoint inhibitors in veterinary medicine was anti-PD-L1 antibody trials conducted by Dr. Konnai’s research team at Hokkaido University, with papers published in 2017 and 2021 [29, 30]. In these clinical trials, anti-PD-L1 antibodies were administered primarily to dogs with oral malignant melanoma, and although the response rate was low (7.7–14.3%), dramatic results were observed, including the disappearance of lung metastases in some cases. An overall survival benefit (median of 143 days) was also observed in dogs treated with the anti-PD-L1 antibody compared with the historical control group. In 2020, Dr. Mizuno’s research team at Yamaguchi University reported a clinical trial of anti-PD-1 antibody drugs administered mainly to dogs with oral malignant melanoma [13]. Although the response rate in this clinical trial was relatively low at 16.7%, shrinkage of lung metastases was observed in some dogs with stage IV disease, and an overall survival benefit (median 166 days) was observed compared to the historical control group. Overall, the response rate for antibody drugs targeting the immune checkpoint molecules PD-1 and PD-L1 is low (approximately 10%) but very promising, as responders can show tumor shrinkage even in late-stage disease. A future challenge is to establish biomarkers that can predict which cases will benefit from immune checkpoint inhibitors. A recent study reported a canine antibody drug against CTLA-4, another important immune checkpoint molecule; however, clinical trials of the anti-CTLA-4 antibody in dogs have not yet been reported [32].

Table 1. Canine clinical trials of novel molcular-targeted therapies.

| Molecular-targeted therapy | Drug type | Target molecules | Target tumors | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ch-4F12-E6 (ca-4F12-E6) | Antibody drug | PD-1 | Oral malignant melanoma | [13] |

| Other cancer | ||||

| c4G12 | Antibody drug | PD-L1 | Oral malignant melanoma | [29, 30] |

| Undifferentiated sarcoma | ||||

| Ibrutinib | Small molecule compound | Burton’s tyrosine kinase | Multicentric lymphoma (B cell) | [12] |

| Acalabrutinib | Small molecule compound | Burton’s tyrosine kinase | Multicentric lymphoma (B cell) | [11] |

| RV1001 | Small molecule compound | PI3 kinase | Multicentric lymphoma (T/B cell) | [7] |

| KPT-335 | Small molecule compound | XPO-1 | Multicentric lymphoma (T/B cell) | [38] |

| STA-1474 | Small molecule compound | Heat shock protein 90 | Mast cell tumor | [20] |

| ADXS31-164 | Recombinant Listeria vaccine | HER2 | Osteosarcoma | [33] |

| 5-azacitidin | Small molecule compound | DNA methyltransferase | Transitional cell carcinoma | [9] |

| EC0905 | Folate-combined agent | Folate receptor | Transitional cell carcinoma | [5] |

| EC0531 | Folate-combined agent | Folate receptor | Transitional cell carcinoma | [43] |

| EGF-combined anthrax toxin | Recombinant protein | EGFR | Transitional cell carcinoma | [14] |

| Vemurafenib | Small molecule compound | BRAF | Transitional cell carcinoma | [37] |

| Lapatinib | Small molecule compound | EGFR, HER2 | Transitional cell carcinoma | [26] |

| Mogamulizumab | Antibody drug | CCR4 | Transitional cell carcinoma | [22, 23] |

| Prostate cancer |

BRAF, v-raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B1; CCR4, CC chemokine receptor 4; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; PD-1, programmed cell death 1; PD-L1, programmed cell death ligand 1; XPO-1, exportin 1.

Next, the author is interested in Burton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitors (Table 1). BTK is a non-receptor tyrosine kinase downstream of the B-cell receptor (BCR) and is an important signaling molecule for B-lymphocyte differentiation, growth, and activation. Ibrutinib is a selective BTK inhibitor that was approved for use in human mantle cell lymphoma in 2013, just 6 years after its development in 2007; a 2010 clinical trial in dogs with multicentric B-cell lymphoma accelerated this early approval [12]. This study was a milestone in demonstrating the usefulness of canine clinical cases in preclinical trials for humans, and Forbes, the global economic magazine, recognized the efforts of this study. Subsequently, a clinical trial of acalabrutinib with greater selectivity and affinity for BTK was also conducted in dogs with multicentric B-cell lymphoma [11].

Another point of interest for the authors was the target disease for which novel agents were administered. As shown in Table 1, the most common tumor type in clinical trials was transitional cell carcinoma, followed by multicentric lymphoma. The number of clinical trials for multicentric lymphomas is high since lymphoma accounts for 10–20% of all canine tumors; additionally, canine cases are relatively easy to recruit compared to human cases for clinical trials. In contrast, transitional cell carcinoma accounts for approximately 2% of all canine tumors, making it a relatively rare occurrence. Transitional cell carcinoma is the most common target of clinical trials for new molecular-targeted drugs as there is no effective treatment. While surgery is generally the first-line treatment for solid tumors, it is often not indicated for transitional cell carcinoma because the tumor cells tend to invade and spread easily, and total cystectomy is associated with significant complications such as urinary incontinence and pyelonephritis. Therefore, it is easy to include these new drugs in clinical trials. Another reason is that Professor Knapp at Perdue University is actively conducting clinical trials on canine transitional cell carcinomas. Dr. Knapp is a pioneer in translational research, using canine clinical cases as an appropriate animal model for human tumors and focusing on the similarities between canine transitional cell carcinoma and human bladder cancer. Dr. Knapp’s research team has conducted several veterinarian-initiated clinical trials in dogs with transitional cell carcinoma, pioneering the use of new agents in development prior to human medicine, which may be a major factor in making transitional cell carcinoma the tumor type with the most clinical trials of new drugs in dogs. In the next section, we discuss the current trending topic and novel molecular-targeted drugs for canine transitional cell carcinoma.

NOVEL MOLECULAR-TARGETED DRUGS FOR CANINE TRANSITIONAL CELL CARCINOMA

Multi-kinase inhibitor: toceranib

Toceranib is a molecular-targeted drug that inhibits PDGFR, VEGFR, and KIT and is also a multi-kinase inhibitor that exerts inhibitory effects on other molecules such as FLT3, CSFR-1, and RET. The efficacy of toceranib in canine mast cell tumors was demonstrated in a multicenter, randomized, double-blind phase III clinical trial, which was approved in 2009 for the treatment of recurrent mast cell tumors [21]. The therapeutic effect of toceranib in mast cell tumors may be mainly due to the inhibition of KIT, as the response rate is associated with c-KIT mutations. Toceranib also inhibits molecules involved in angiogenesis, such as PDGFR and VEGFR, and is, therefore, used in canine malignancies other than mast cell tumors. The efficacy of toceranib has been confirmed in apocrine gland anal sac adenocarcinoma, thyroid cancer, and gastrointestinal stromal tumor [3, 18]. As tumor cells express high levels of PDGFR and VEGFR in canine transitional cell carcinoma, the efficacy of toceranib was anticipated [47]. Recently, a retrospective study reported the efficacy of toceranib for the treatment of canine transitional cell carcinoma. Unfortunately, the results were not significantly more effective than conventional therapy: 7% partial remission (PR), 80% stable disease (SD), and 13% progressive disease (PD), with a median progression-free survival (PFS) of 96 days and median overall survival (OS) of 149 days [8]. However, more than 90% of transitional cell carcinoma cases in this study had already been treated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or anticancer agents. Although a few dogs achieved partial remission, the clinical benefit rate was 87%, suggesting that toceranib inhibited tumor progression in many cases. Further clinical trials are needed to evaluate the efficacy of toceranib as a first-line therapy or in combination with NSAIDs or anticancer agents.

DNA methyltransferase inhibitor: 5-azacitidine

Decreased expression and disruption of tumor suppressor genes is evident in various tumors and are associated with tumorigenesis. Traditionally, the loss of tumor suppressor gene function owing to mutations causes tumor initiation and progression. However, epigenetic abnormalities, such as DNA methylation and histone acetylation, are also the causative factors for the decreased expression of tumor suppressor genes. Increased gene expression of DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1), an enzyme that promotes DNA methylation, and hypermethylation of CDKN2A, a tumor suppressor gene, has been reported in canine transitional cell carcinoma, suggesting that abnormal DNA methylation is associated with development and progression in dogs [4, 9]. Five-azacitidine, used to treat myelodysplastic syndrome in humans, inhibits DNA methylation by suppressing DNA methyltransferase activity [15]. In 2012, a phase I study of 5-azacitidine for canine transitional cell carcinoma was reported [9]. As this was a pilot study, survival was not evaluated; nonetheless, some therapeutic efficacy was observed, with 22% PR, 50% SD, and 28% PD. However, severe neutropenia (VCOG-CTECAE grade 3 or 4) was reported as an adverse event of 5-azacitidine in approximately 30% of dogs therefore, further studies with adjusted dosage and dosing intervals are necessary.

Folate-combined anticancer agents

Tumor cells express folate receptors at higher levels than normal cells and actively take up folate (vitamin B9). Folate is important for the synthesis of amino acids and DNA and is therefore a necessary nutrient for active cell division in tumor cells. Folate receptors are highly expressed in more than 75% of cases with canine transitional cell carcinoma [5, 43]. A drug delivery system that combines folate with an anticancer drug has been developed to allow selective uptake of the drug by tumor cells expressing high levels of folate receptors, and two clinical trials have been conducted for canine transitional cell carcinoma [5, 43]. In a 2013 clinical trial, a drug called EC0905, which combines folate with vinblastine, was administered to dogs with folate receptor-positive transitional cell carcinoma, with a good response rate of 56% PR, 44% SD, and no PD. Unfortunately, the study did not provide prognostic information such as PFS or OS [5]. In 2018, the same group conducted a clinical trial in dogs with folate receptor-positive transitional cell carcinoma using a drug called EC0531, which combines folate with tubulysin, with 11% PR, 61% SD, 28% PD, and a median PFS of 103 days [43]. Mild-to-moderate gastrointestinal symptoms (vomiting, diarrhea, anorexia, and weight loss), decreased activity, and neutropenia were observed as adverse events for both EC0905 and EC0531. Although the results are not significantly more effective than conventional therapies, the folate receptor-mediated drug delivery system is promising, and future investigations of new drugs combining folate with other anticancer agents are anticipated.

EGF-combined anthrax toxin

Epidermal growth factor (EGF) is a molecule that promotes cell growth and proliferation by binding to its receptor EGFR, which is highly expressed in a variety of tumors and is associated with tumor development and progression through excessive growth signaling. EGFR overexpression has been reported in 72% of canine transitional cell carcinoma cases [10]. A molecular-targeted drug combining anthrax toxin with EGF has been developed [14]. Anthrax toxins consist of three types of proteins: protective antigens, edema factors, and lethal factors. Once bound to the cell surface, protective antigens assemble on the plasma membrane to form a heptamer that is internalized by endocytosis. Since septameric protective antigens can bind to edema factors or lethal factors, these factors are simultaneously internalized as protective antigens. Intracellularly incorporated edema factors induce the intracellular secretion of water and electrolytes via an increase in cyclic AMP, resulting in tissue edema. The lethal factor is a proteolytic enzyme that degrades MAP kinase kinase (MAPKK), which is important in cell signaling. When MAPKK are degraded, signaling does not occur normally, and the cell that has taken up the lethal factor dies. Therefore, the uptake of lethal factors by protective antigens is critical for the toxic effects of anthrax toxins. EGF-binding anthrax toxin was designed to specifically target EGFR-overexpressing tumor cells by replacing the cell membrane-binding region of the protective antigen with EGF. A pilot study in which EGF-binding anthrax toxin was injected into the bladders of six dogs with transitional cell carcinoma was reported in 2020, and a trend toward mass reduction was observed in all cases, although no PR was observed [14]. Notably, mild cystitis symptoms (hematuria and frequent urination for 2 days) were observed in one of six dogs receiving intravesical administration of EGF-binding anthrax toxin, although no apparent adverse events were reported in the other cases. In the future, the efficacy and safety of this drug should be verified through large-scale clinical trials and its commercialization as a novel molecular-targeted drug.

BRAF inhibitor: vemurafenib

BRAF is a kinase that comprises a signaling pathway known as the MAP kinase pathway. In humans, several BRAF mutations have been reported in a variety of tumors, including malignant melanoma, colorectal cancer, lung cancer, and thyroid cancer, among which the BRAFV600E mutation is the most common. Mutant BRAF is involved in tumor development and progression by causing sustained activation without upstream RAS activation, inducing tumor cell growth and survival, and promoting angiogenesis. BRAF inhibitors such as vemurafenib, dabrafenib, and encorafenib have been approved for the treatment of malignant melanoma with BRAF gene mutations. In 2015, the BRAFV595E mutation was reportedly found in 70–80% of canine transitional cell carcinomas [34, 35]. As this mutation is homologous to the human BRAFV600E mutation, BRAF inhibitors are expected to be effective as a new molecular-targeted therapy for dogs with transitional cell carcinoma. In 2021, a clinical trial reported that vemurafenib was administered to 24 dogs with BRAF mutation-positive transitional cell carcinoma, resulting in 38% PR, 54% SD, and 8% PD, with a median PFS of 181 days and a median OS of 354 days [37]. These results represent one of the best response rates and survival outcomes reported to date for medical therapies. Because vemurafenib was used as a single agent in this clinical trial, its combination with NSAIDs may further improve outcomes. BRAF inhibitors show promise as molecular-targeted therapies for canine transitional cell carcinoma; however, they also present the challenge of adverse events. Six of 24 dogs (18%) treated with vemurafenib had post-treatment skin masses that were histologically confirmed as squamous cell papillomas or squamous cell carcinomas [37]. Skin tumors have also been reported as an adverse event associated with BRAF inhibitors in humans. Owing to the significant risk of tumor development as an adverse outcome, it is imperative that owners are provided with complete information.

DEVELOPMENT OF NOVEL THERAPEUTIC STRATEGY FOR CANINE TRANSITIONAL CELL CARCINOMA

The previous section presented reports of new molecular-targeted therapies for canine transitional cell carcinoma published overseas (mostly by Dr. Knapp’s research team). The author’s research team has also been actively conducting veterinarian-initiated clinical trials of novel molecular-targeted therapies for canine transitional cell carcinoma and has published the results of these trials. This section summarizes the efforts of the authors’ research team.

HER2 inhibitor: lapatinib

HER2 is a receptor-type tyrosine kinase belonging to the EGFR family that is involved in tumor progression, including cell proliferation, survival, differentiation, migration, and angiogenesis. In veterinary medicine, HER2 overexpression has been reported in canine mammary carcinoma and osteosarcoma, and the efficacy of HER2-targeted immunotherapy against osteosarcoma has been demonstrated [33]. Our research group has comprehensively analyzed gene expression in tumor tissues to explore new therapeutic targets for canine transitional cell carcinoma. We found that the HER2 signaling pathway is significantly activated in transitional cell carcinoma [27]. We then evaluated HER2 protein expression and HER2 gene amplification using immunohistochemistry and digital PCR, respectively, and found that HER2 protein overexpression and HER2 gene amplification were observed in canine transitional cell carcinoma in some cases [40, 44]. Furthermore, the efficacy of lapatinib, a dual inhibitor of EGFR and HER2, against canine transitional cell carcinoma was confirmed using cell lines and a tumor-engrafted mouse model [39]. Based on these results, a veterinarian-initiated clinical trial of lapatinib was conducted in dogs with transitional cell carcinoma [26]. The results were favorable: 3% complete remission (CR), 52% PR, 34% SD, and 11% PD, with a median PFS of 193 days and median OS of 435 days. Adverse events were relatively mild with rare serious adverse events, although occasionally elevated liver enzymes, gastrointestinal symptoms (vomiting, diarrhea, and anorexia), and skin pigmentation were observed. Notably, lapatinib, which is metabolized in the liver, has low nephrotoxicity, making it easier to use against transitional cell carcinoma developing in the urinary tract. Therefore, lapatinib is a promising new molecular-targeted therapy for canine transitional cell carcinoma.

This study also evaluated predictive biomarkers of lapatinib efficacy [26]. Dogs with transitional cell carcinoma, whose tumor cells exhibited HER2 overexpression or HER2 gene amplification, showed greater efficacy of lapatinib. The presence of KIT gene mutations is associated with the therapeutic efficacy of imatinib in canine mast cell tumors, although no useful biomarkers have been found to predict the efficacy of molecular-targeted drugs. The authors believe that the discovery of the HER2 test for predicting the efficacy of lapatinib may be a breakthrough in canine cancer treatment.

Anti-CCR4 antibody: mogamulizumab

CCR4 is a receptor for chemokine CCL17, a molecule involved in lymphocyte migration and infiltration. In the context of allergy, CCL17 and CCR4 are important in the pathogenesis of canine atopic dermatitis. Th2 cells are T-lymphocytes that are important in the pathogenesis of allergy and express CCR4. In canine atopic dermatitis, CCR4-positive Th2 cells migrate to the lesional skin via CCL17 produced by keratinocytes. The percentage of CCR4-positive helper T cells (Th2 cells) in peripheral blood is increased in cases with canine atopic dermatitis compared to healthy dogs [25]. The author’s research group has shown that CCR4 is highly expressed not only in Th2 cells but also in immunosuppressive T-lymphocytes called regulatory T cells (Tregs) and plays an important role in the infiltration of Tregs into tumor tissues [22,23,24].

Tregs are important T lymphocytes involved in the termination of inflammation and immune tolerance but play a promotive role in tumor progression by suppressing anti-tumor immunity. We examined Treg infiltration in canine tumor tissues using immunohistochemistry and found that large numbers of Tregs were infiltrated in transitional cell carcinoma, prostate cancer, mammary carcinoma, lung adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and malignant melanoma and that their number was associated with survival time [22, 23, 41]. In addition, a comprehensive analysis of the molecules involved in Treg infiltration revealed that tumor-infiltrating Tregs highly express CCR4 and that the chemokine CCL17, a ligand for CCR4, is produced in large amounts by tumor cells. We then conducted a veterinarian-initiated clinical trial of mogamulizumab, an anti-human CCR4 antibody drug that cross-reacts with canine CCR4, in dogs with transitional cell carcinoma [23]. We found that CCR4 inhibition suppressed Treg infiltration into tumor tissues and activated anti-tumor immunity, resulting in a therapeutic effect. The efficacy of mogamulizumab in dogs with transitional cell carcinoma was 71% PR, 29% SD, and no PD, with a median PFS of 189 days and a median OS of 474 days [23]. However, only 14 dogs with transitional cell carcinoma were administered mogamulizumab in this clinical trial. Therefore, we continued to increase the number of cases.

The benefit of mogamulizumab treatment in dogs with transitional cell carcinoma was recently confirmed in 32 cases, including results from 14 previously published cases [23] and those of 18 additional dogs at the Veterinary Medical Center of the University of Tokyo between 2019 and 2022. The 32 dogs treated with mogamulizumab in combination with piroxicam included six males (all neutered) and 26 females (two intact and 24 neutered), with a median age of 12.8 years (range 7.1–17.8 years). According to the WHO TNM classification for canine bladder cancer [6, 36], 23 of 32 (72%) dogs were classified as T2N0M0, two (6%) as T2N0M1, one (3%) as T2N1M1, four (13%) as T3N0M0, and two (6%) as T3N1M0. Lymph node and distant (to the lung) metastases were observed in three (9%) cases each. Of the 32 dogs treated with mogamulizumab/piroxicam, 17 (53%) showed PR, 13 (41%) showed SD, and two (6%) showed PD. At the endpoint (May 1, 2023), nine (28%) mogamulizumab-treated dogs had survived. The median PFS and OS in dogs that received mogamulizumab/piroxicam were 228 days (range 67–573 days) and 468 days (range 231–1185 days), respectively. To confirm whether mogamulizumab treatment prolongs survival in canine transitional cell carcinoma, we compared the PFS and OS of cases treated with mogamulizumab/piroxicam with those of a historical control group (cases treated with piroxicam alone; n=42) in our previous study [26]. The median PFS and OS in dogs treated with piroxicam alone were 90 (range, 21–318) days and 216 (range, 41–725) days, respectively [26]. PFS and OS were longer in dogs treated with mogamulizumab/piroxicam than in those treated with piroxicam alone (Fig. 2). In addition to canine transitional cell carcinoma, we reported a clinical trial of mogamulizumab for canine prostate cancer in 2022 [22]. The efficacy of mogamulizumab/piroxicam in dogs with prostate cancer was 30% PR, 61% SD, and 9% PD, with a median PFS of 204 days and a median OS of 312 days [22]. These results for mogamulizumab/piroxicam in canine transitional cell carcinoma and prostate cancer compared favorably with conventional therapies.

Fig. 2.

Progression-free survival (A) and overall survival (B) in dogs treated with mogamulizumab in combination with piroxicam (n=32, green) and historical control (n=42, yellow). Log-rank test.

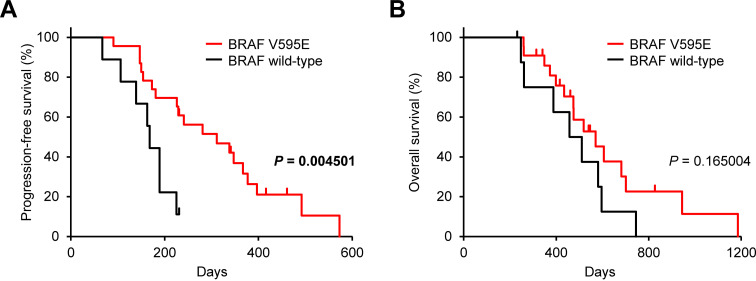

We recently showed that the BRAFV595E somatic mutation induces CCL17 production and contributes to Treg infiltration in dogs with transitional cell carcinoma and prostate cancer [22, 28]. Thus, further analyses investigated whether the BRAFV595E mutation influenced the clinical response to mogamulizumab treatment. Of the 32 transitional cell carcinoma cases treated with mogamulizumab/piroxicam in this study, the BRAFV595E mutation was detected in 23 (72%) cases. In these dogs, PFS, but not OS, was longer in cases with the BRAFV595E mutation than in those with the wild-type BRAF (Fig. 3). Similar to transitional cell carcinoma cases, the likelihood of response to mogamulizumab therapy (tumor burden reduction and survival) can be increased by determining the BRAFV595E somatic mutation in dogs with prostate cancer [22], suggesting that the BRAFV595E mutation is a useful biomarker for predicting the clinical response and outcome of mogamulizumab treatment.

Fig. 3.

Progression-free survival (A) and overall survival (B) according to v-raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B1 (BRAF) gene status in dogs treated with mogamulizumab in combination with piroxicam (n=32). Nine cases had wild-type BRAF (black) and 23 had BRAFV595E mutation (red). Log-rank test.

Mogamulizumab treatment in dogs is well tolerated, with grade 1 or 2 treatment-related adverse events [22, 23]. Vomiting and anorexia were manageable with systemic antiemetic therapy alone. Immune-related adverse events such as pancreatitis, urticaria, rash, and infusion reactions were observed but were mild. These safety data, including the lack of nephrotoxicity, suggest that older dogs with transitional cell carcinoma or prostate cancer who are more prone to renal failure may tolerate mogamulizumab treatment better than chemotherapy.

DOGS AS A SPONTANEOUS ANIMAL MODEL OF CANCER

In cancer research, mouse models, such as carcinogen models, genetically engineered mouse models, xenograft models, and allograft models have been widely used as animal models. Although the importance of mouse models in the development of cancer research is obvious, it has recently been pointed out that mouse models have many disadvantages. For example, the lack of diversity in mice owing to homogeneous genetic and environmental backgrounds, cancer phenotypes and methods of evaluating therapeutic efficacy differ greatly from those in humans, and evaluation of immunotherapy is difficult in immunodeficient mice. The success rate of extrapolation from mouse models to human clinical trials in cancer drug discovery is less than 10% [31], and a gap called the “valley of death” exists between basic research and clinical trials. To overcome this valley of death, translational research using spontaneous canine cancer models has been advocated in recent publications [2, 16, 17, 42]. Dogs spontaneously develop a variety of cancers, and their symptoms, metastatic patterns, pathology, and immune systems are similar to those of humans. Additionally, dogs can be evaluated over time using the same testing methods as humans, such as blood tests and diagnostic imaging. In addition, some types of cancers, such as prostate cancer, bladder cancer, lymphoma, melanoma, and osteosarcoma, have similar gene expression patterns in dogs and humans [2, 17, 22]. As mentioned in this review, several veterinarian-initiated clinical trials using novel agents not approved for human patients in canine oncology cases, and successful results have been reported, suggesting that canine tumor cases are very useful as “spontaneous animal models of cancer”.

CONCLUSION

This review summarizes papers on molecular-targeted drugs for canine tumors published in the span of 15 years from the 2008 report of masitinib to the present and proposes that the “second era of molecular-targeted drugs” has emerged in veterinary medicine. The author opines that the introduction of new molecular-targeted drugs in veterinary medicine is imminent. In addition, translational clinical trials in dogs using novel molecular-targeted drugs may provide crucial information for cancer treatment in humans. The “beyond species” comparative oncology efforts in veterinary and human medicine play an important and growing role in cancer research and drug development.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the canine patients, owners, and clinical care team at the Veterinary Medical Center of the University of Tokyo for their assistance in the work summarized in this article. This study was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (grant number, JP19H00968) and an Anicom Capital Research Grant (EVOLVE).

REFERENCES

- 1.Attwood MM, Fabbro D, Sokolov AV, Knapp S, Schiöth HB. 2021. Trends in kinase drug discovery: targets, indications and inhibitor design. Nat Rev Drug Discov 20: 839–861. doi: 10.1038/s41573-021-00252-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beltrán Hernández I, Kromhout JZ, Teske E, Hennink WE, van Nimwegen SA, Oliveira S. 2021. Molecular targets for anticancer therapies in companion animals and humans: what can we learn from each other? Theranostics 11: 3882–3897. doi: 10.7150/thno.55760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berger EP, Johannes CM, Jergens AE, Allenspach K, Powers BE, Du Y, Mochel JP, Fox LE, Musser ML. 2018. Retrospective evaluation of toceranib phosphate (Palladia®) use in the treatment of gastrointestinal stromal tumors of dogs. J Vet Intern Med 32: 2045–2053. doi: 10.1111/jvim.15335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dhawan D, Ramos-Vara JA, Hahn NM, Waddell J, Olbricht GR, Zheng R, Stewart JC, Knapp DW. 2013. DNMT1: an emerging target in the treatment of invasive urinary bladder cancer. Urol Oncol 31: 1761–1769. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2012.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dhawan D, Ramos-Vara JA, Naughton JF, Cheng L, Low PS, Rothenbuhler R, Leamon CP, Parker N, Klein PJ, Vlahov IR, Reddy JA, Koch M, Murphy L, Fourez LM, Stewart JC, Knapp DW. 2013. Targeting folate receptors to treat invasive urinary bladder cancer. Cancer Res 73: 875–884. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fulkerson CM, Knapp DW. 2015. Management of transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder in dogs: a review. Vet J 205: 217–225. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2015.01.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gardner HL, Rippy SB, Bear MD, Cronin KL, Heeb H, Burr H, Cannon CM, Penmetsa KV, Viswanadha S, Vakkalanka S, London CA. 2018. Phase I/II evaluation of RV1001, a novel PI3Kδ inhibitor, in spontaneous canine lymphoma. PLoS One 13: e0195357. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0195357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gustafson TL, Biller B. 2019. Use of toceranib phosphate in the treatment of canine bladder tumors: 37 cases. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 55: 243–248. doi: 10.5326/JAAHA-MS-6905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hahn NM, Bonney PL, Dhawan D, Jones DR, Balch C, Guo Z, Hartman-Frey C, Fang F, Parker HG, Kwon EM, Ostrander EA, Nephew KP, Knapp DW. 2012. Subcutaneous 5-azacitidine treatment of naturally occurring canine urothelial carcinoma: a novel epigenetic approach to human urothelial carcinoma drug development. J Urol 187: 302–309. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.09.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanazono K, Fukumoto S, Kawamura Y, Endo Y, Kadosawa T, Iwano H, Uchide T. 2015. Epidermal growth factor receptor expression in canine transitional cell carcinoma. J Vet Med Sci 77: 1–6. doi: 10.1292/jvms.14-0032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harrington BK, Gardner HL, Izumi R, Hamdy A, Rothbaum W, Coombes KR, Covey T, Kaptein A, Gulrajani M, Van Lith B, Krejsa C, Coss CC, Russell DS, Zhang X, Urie BK, London CA, Byrd JC, Johnson AJ, Kisseberth WC. 2016. Preclinical evaluation of the novel BTK inhibitor acalabrutinib in canine models of B-cell non-hodgkin lymphoma. PLoS One 11: e0159607. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Honigberg LA, Smith AM, Sirisawad M, Verner E, Loury D, Chang B, Li S, Pan Z, Thamm DH, Miller RA, Buggy JJ. 2010. The Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor PCI-32765 blocks B-cell activation and is efficacious in models of autoimmune disease and B-cell malignancy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 13075–13080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004594107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Igase M, Nemoto Y, Itamoto K, Tani K, Nakaichi M, Sakurai M, Sakai Y, Noguchi S, Kato M, Tsukui T, Mizuno T. 2020. A pilot clinical study of the therapeutic antibody against canine PD-1 for advanced spontaneous cancers in dogs. Sci Rep 10: 18311. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-75533-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jack S, Madhivanan K, Ramadesikan S, Subramanian S, Edwards DF, 2nd, Elzey BD, Dhawan D, McCluskey A, Kischuk EM, Loftis AR, Truex N, Santos M, Lu M, Rabideau A, Pentelute B, Collier J, Kaimakliotis H, Koch M, Ratliff TL, Knapp DW, Aguilar RC. 2020. A novel, safe, fast and efficient treatment for Her2-positive and negative bladder cancer utilizing an EGF-anthrax toxin chimera. Int J Cancer 146: 449–460. doi: 10.1002/ijc.32719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keating GM. 2009. Azacitidine: a review of its use in higher-risk myelodysplastic syndromes/acute myeloid leukaemia. Drugs 69: 2501–2518. doi: 10.2165/11202840-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kol A, Arzi B, Athanasiou KA, Farmer DL, Nolta JA, Rebhun RB, Chen X, Griffiths LG, Verstraete FJ, Murphy CJ, Borjesson DL. 2015. Companion animals: translational scientist’s new best friends. Sci Transl Med 7: 308ps21. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa9116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.LeBlanc AK, Mazcko CN. 2020. Improving human cancer therapy through the evaluation of pet dogs. Nat Rev Cancer 20: 727–742. doi: 10.1038/s41568-020-0297-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.London C, Mathie T, Stingle N, Clifford C, Haney S, Klein MK, Beaver L, Vickery K, Vail DM, Hershey B, Ettinger S, Vaughan A, Alvarez F, Hillman L, Kiselow M, Thamm D, Higginbotham ML, Gauthier M, Krick E, Phillips B, Ladue T, Jones P, Bryan J, Gill V, Novasad A, Fulton L, Carreras J, McNeill C, Henry C, Gillings S. 2012. Preliminary evidence for biologic activity of toceranib phosphate (Palladia®) in solid tumours. Vet Comp Oncol 10: 194–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5829.2011.00275.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.London CA. 2009. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors in veterinary medicine. Top Companion Anim Med 24: 106–112. doi: 10.1053/j.tcam.2009.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.London CA, Acquaviva J, Smith DL, Sequeira M, Ogawa LS, Gardner HL, Bernabe LF, Bear MD, Bechtel SA, Proia DA. 2018. Consecutive day HSP90 inhibitor administration improves efficacy in murine models of KIT-driven malignancies and canine mast cell tumors. Clin Cancer Res 24: 6396–6407. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-0703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.London CA, Malpas PB, Wood-Follis SL, Boucher JF, Rusk AW, Rosenberg MP, Henry CJ, Mitchener KL, Klein MK, Hintermeister JG, Bergman PJ, Couto GC, Mauldin GN, Michels GM. 2009. Multi-center, placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized study of oral toceranib phosphate (SU11654), a receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, for the treatment of dogs with recurrent (either local or distant) mast cell tumor following surgical excision. Clin Cancer Res 15: 3856–3865. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maeda S, Motegi T, Iio A, Kaji K, Goto-Koshino Y, Eto S, Ikeda N, Nakagawa T, Nishimura R, Yonezawa T, Momoi Y. 2022. Anti-CCR4 treatment depletes regulatory T cells and leads to clinical activity in a canine model of advanced prostate cancer. J Immunother Cancer 10: 10. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2021-003731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maeda S, Murakami K, Inoue A, Yonezawa T, Matsuki N. 2019. CCR4 blockade depletes regulatory T cells and prolongs survival in a canine model of bladder cancer. Cancer Immunol Res 7: 1175–1187. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-18-0751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maeda S, Nakazawa M, Uchida M, Yoshitake R, Nakagawa T, Nishimura R, Miyamoto R, Bonkobara M, Yonezawa T, Momoi Y. 2020. Foxp3+ regulatory T cells associated with CCL17/CCR4 expression in carcinomas of dogs. Vet Pathol 57: 497–506. doi: 10.1177/0300985820921535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maeda S, Ohmori K, Yasuda N, Kurata K, Sakaguchi M, Masuda K, Ohno K, Tsujimoto H. 2004. Increase of CC chemokine receptor 4-positive cells in the peripheral CD4 cells in dogs with atopic dermatitis or experimentally sensitized to Japanese cedar pollen. Clin Exp Allergy 34: 1467–1473. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.02039.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maeda S, Sakai K, Kaji K, Iio A, Nakazawa M, Motegi T, Yonezawa T, Momoi Y. 2022. Lapatinib as first-line treatment for muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma in dogs. Sci Rep 12: 4. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-04229-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maeda S, Tomiyasu H, Tsuboi M, Inoue A, Ishihara G, Uchikai T, Chambers JK, Uchida K, Yonezawa T, Matsuki N. 2018. Comprehensive gene expression analysis of canine invasive urothelial bladder carcinoma by RNA-Seq. BMC Cancer 18: 472. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-4409-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maeda S, Yoshitake R, Chambers JK, Uchida K, Eto S, Ikeda N, Nakagawa T, Nishimura R, Goto-Koshino Y, Yonezawa T, Momoi Y. 2020. BRAFV595E mutation associates CCL17 expression and regulatory T cell recruitment in urothelial carcinoma of dogs. Vet Pathol 58: 971–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maekawa N, Konnai S, Nishimura M, Kagawa Y, Takagi S, Hosoya K, Ohta H, Kim S, Okagawa T, Izumi Y, Deguchi T, Kato Y, Yamamoto S, Yamamoto K, Toda M, Nakajima C, Suzuki Y, Murata S, Ohashi K. 2021. PD-L1 immunohistochemistry for canine cancers and clinical benefit of anti-PD-L1 antibody in dogs with pulmonary metastatic oral malignant melanoma. NPJ Precis Oncol 5: 10. doi: 10.1038/s41698-021-00147-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maekawa N, Konnai S, Takagi S, Kagawa Y, Okagawa T, Nishimori A, Ikebuchi R, Izumi Y, Deguchi T, Nakajima C, Kato Y, Yamamoto K, Uemura H, Suzuki Y, Murata S, Ohashi K. 2017. A canine chimeric monoclonal antibody targeting PD-L1 and its clinical efficacy in canine oral malignant melanoma or undifferentiated sarcoma. Sci Rep 7: 8951. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-09444-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mak IW, Evaniew N, Ghert M. 2014. Lost in translation: animal models and clinical trials in cancer treatment. Am J Transl Res 6: 114–118. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mason NJ, Chester N, Xiong A, Rotolo A, Wu Y, Yoshimoto S, Glassman P, Gulendran G, Siegel DL. 2021. Development of a fully canine anti-canine CTLA4 monoclonal antibody for comparative translational research in dogs with spontaneous tumors. MAbs 13: 2004638. doi: 10.1080/19420862.2021.2004638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mason NJ, Gnanandarajah JS, Engiles JB, Gray F, Laughlin D, Gaurnier-Hausser A, Wallecha A, Huebner M, Paterson Y. 2016. Immunotherapy with a HER2-targeting listeria induces HER2-specific immunity and demonstrates potential therapeutic effects in a phase I trial in canine osteosarcoma. Clin Cancer Res 22: 4380–4390. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-0088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mochizuki H, Kennedy K, Shapiro SG, Breen M. 2015. BRAF mutations in canine cancers. PLoS One 10: e0129534. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mochizuki H, Shapiro SG, Breen M. 2015. Detection of BRAF mutation in urine DNA as a molecular diagnostic for canine urothelial and prostatic carcinoma. PLoS One 10: e0144170. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Owen LN. 1980. TNM Classification of Tumours in Domestic Animals, World Health Organization (WHO), Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rossman P, Zabka TS, Ruple A, Tuerck D, Ramos-Vara JA, Liu L, Mohallem R, Merchant M, Franco J, Fulkerson CM, Bhide KP, Breen M, Aryal UK, Murray E, Dybdal N, Utturkar SM, Fourez LM, Enstrom AW, Dhawan D, Knapp DW. 2021. Phase I/II trial of vemurafenib in dogs with naturally occurring, BRAF-mutated urothelial carcinoma. Mol Cancer Ther 20: 2177–2188. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-20-0893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sadowski AR, Gardner HL, Borgatti A, Wilson H, Vail DM, Lachowicz J, Manley C, Turner A, Klein MK, Waite A, Sahora A, London CA. 2018. Phase II study of the oral selective inhibitor of nuclear export (SINE) KPT-335 (verdinexor) in dogs with lymphoma. BMC Vet Res 14: 250. doi: 10.1186/s12917-018-1587-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sakai K, Maeda S, Saeki K, Nakagawa T, Murakami M, Endo Y, Yonezawa T, Kadosawa T, Mori T, Nishimura R, Matsuki N. 2018. Anti-tumour effect of lapatinib in canine transitional cell carcinoma cell lines. Vet Comp Oncol 16: 642–649. doi: 10.1111/vco.12434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sakai K, Maeda S, Saeki K, Yoshitake R, Goto-Koshino Y, Nakagawa T, Nishimura R, Yonezawa T, Matsuki N. 2020. ErbB2 copy number aberration in canine urothelial carcinoma detected by a digital polymerase chain reaction assay. Vet Pathol 57: 56–65. doi: 10.1177/0300985819879445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sakai K, Maeda S, Yamada Y, Chambers JK, Uchida K, Nakayama H, Yonezawa T, Matsuki N. 2018. Association of tumour-infiltrating regulatory T cells with adverse outcomes in dogs with malignant tumours. Vet Comp Oncol 16: 330–336. doi: 10.1111/vco.12383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schiffman JD, Breen M. 2015. Comparative oncology: what dogs and other species can teach us about humans with cancer. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 370: 370. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2014.0231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Szigetvari NM, Dhawan D, Ramos-Vara JA, Leamon CP, Klein PJ, Ruple AA, Heng HG, Pugh MR, Rao S, Vlahov IR, Deshuillers PL, Low PS, Fourez LM, Cournoyer AM, Knapp DW. 2018. Phase I/II clinical trial of the targeted chemotherapeutic drug, folate-tubulysin, in dogs with naturally-occurring invasive urothelial carcinoma. Oncotarget 9: 37042–37053. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.26455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tsuboi M, Sakai K, Maeda S, Chambers JK, Yonezawa T, Matsuki N, Uchida K, Nakayama H. 2019. Assessment of HER2 expression in canine urothelial carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Vet Pathol 56: 369–376. doi: 10.1177/0300985818817024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Valent P, Groner B, Schumacher U, Superti-Furga G, Busslinger M, Kralovics R, Zielinski C, Penninger JM, Kerjaschki D, Stingl G, Smolen JS, Valenta R, Lassmann H, Kovar H, Jäger U, Kornek G, Müller M, Sörgel F. 2016. Paul ehrlich (1854–1915) and his contributions to the foundation and birth of translational medicine. J Innate Immun 8: 111–120. doi: 10.1159/000443526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Waldman AD, Fritz JM, Lenardo MJ. 2020. A guide to cancer immunotherapy: from T cell basic science to clinical practice. Nat Rev Immunol 20: 651–668. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0306-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Walters L, Martin O, Price J, Sula MM. 2018. Expression of receptor tyrosine kinase targets PDGFR-β, VEGFR2 and KIT in canine transitional cell carcinoma. Vet Comp Oncol 16: E117–E122. doi: 10.1111/vco.12344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]