Abstract

Objective

To characterize the relationships between social determinants of health (SDOH) and outcomes for children born extremely preterm.

Study Design

This is a cohort study of infants born at 22–26 weeks’ gestation in NICHD Neonatal Research Network centers (2006–2017) who survived to discharge. Infants were classified by three maternal SDOH: education, insurance, and race. Outcomes included postmenstrual age (PMA) at discharge, readmission, neurodevelopmental impairment (NDI), and death post-discharge. Regression analyses adjusted for center, perinatal characteristics, neonatal morbidity, ethnicity, and two SDOH (eg, group comparisons by education adjusted for insurance and race).

Results

Of 7438 children, 5442 (73%) had at least one risk-associated SDOH. PMA at discharge was older (adjusted mean difference 0.37 weeks, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.06–0.68) and readmission more likely (adjusted odds ratio (aOR) 1.27, 95% CI 1.12–1.43) for infants whose mothers had public/no insurance versus private. Neither PMA at discharge nor readmission varied by education or race. NDI was twice as likely (aOR 2.36, 95% CI 1.86–3.00) and death five times as likely (aOR 5.22, 95% CI 2.54–10.73) for infants with three risk-associated SDOH compared with those with none.

Conclusions

Children born to mothers with public/no insurance were older at discharge and more likely to be readmitted than those born to privately insured mothers. NDI and death post-discharge were more common among children exposed to multiple risk-associated SDOH at birth compared with those not exposed. Addressing disparities due to maternal education, insurance coverage, and systemic racism are potential intervention targets to improve outcomes for children born preterm.

Keywords: Premature, discharge, neurodevelopment, education, insurance, race

Introduction

Social determinants of health (SDOH) are non-medical factors that influence health outcomes of children even before birth.(1, 2) Maternal SDOH relevant to childhood outcomes for children born preterm include education level,(3, 4) insurance status,(5, 6) and race(7, 8) as a marker of systemic racism. In one longitudinal birth cohort, SDOH accounted for 35% of the total variance in cognition for low birth weight children at 9 years while birth weight and gestational age accounted for only 9% of the variance.(9) In the ELGAN cohort, children whose mothers had low education levels were more likely to score ≥2 standard deviations below the norm for language, academic achievement, and executive functioning at 10 years.(10) Infant mortality in the United States varies by maternal insurance status with the lowest mortality rate in infants born to mothers with private insurance.(11)To optimize outcomes of children born preterm, it is necessary to identify and address SDOH associated with disadvantage.

Embedded within SDOH are structural determinants of health, such as systemic racism, which adversely impact health through epigenetic activity, psychologic stress, and inequities in education, housing, employment, or income.(12) Perinatal care in the United States is fraught with racism-rooted disparities.(7, 8, 13–15) The infant mortality rate is significantly higher for Black infants than White infants.(16, 17) Perinatal mortality disparities persist for well-educated Black mother-infant dyads compared with White dyads.(18–20) In a secondary analysis of the Assessment of Perinatal EXcellence study, the crude frequency of adverse perinatal outcomes for term newborns differed by race; however, after adjusting for insurance status, the difference was no longer significant.(21) This highlights the need to consider multiple SDOH concurrently and to account for SDOH in analyses.

There is an opportunity to better understand how SDOH relate to outcomes of children born extremely preterm. The current study characterizes discharge characteristics, readmission occurrence, neurodevelopmental impairment (NDI), and death post-discharge through the lens of three SDOH exposures: race, education level, and insurance status.

Methods

This was a secondary analysis of a prospective cohort of infants born at 220/7-266/7 weeks’ gestation at NRN centers between January 1, 2006, and December 31, 2017, who survived to discharge. Infants were included if their mothers identified as either Black or White race. Self-reported maternal race was abstracted from the medical record to use as a marker for systemic racism.(19, 22) Infants whose mothers identified as American Indian or Alaskan Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and more than one race were not included due to constraints related to analyzing race as a binary variable. Follow-up occurred at 18–22 months’ corrected age for infants born prior to July 2012 and at 22–26 months’ corrected age for those born in July 2012 or later. To reduce loss to follow-up and minimize bias, NRN centers attempted to maintain contact between discharge and the comprehensive neurodevelopmental follow-up at 18–26 months’ corrected age. Data collection for the NRN databases was approved by each site’s institutional review board, and parental consent was obtained if required by the local institutional review board. Infants who were outborn, died prior to discharge, or who had major congenital anomalies were excluded.

Infants were classified by maternal SDOH at birth as binary variables: education (less than high school graduate or high school graduate), insurance status (public/none or private), and race (Black or White). Less than high school education, public/no insurance, and non-White race were considered SDOH exposures associated with social disadvantage and health disparities, henceforth referred to as risk-associated SDOH. Ethnicity was not analyzed as a separate SDOH due to concern for potential masking of differences given the Hispanic paradox,(23) an epidemiological phenomenon in which individuals of Hispanic ethnicity have better health outcomes than non-Hispanic individuals despite socioeconomic disadvantage in the United States.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was PMA at discharge. Secondary outcomes were PMA discharge quartile, discharge with oxygen, readmission, NDI, or death post-discharge. Neurodevelopmental follow-up included the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development, Third Edition (Bayley-III), to assess cognitive, language, and motor skills.(24) NDI was defined as any of the following: moderate or severe cerebral palsy, gross motor function classification system level 2 or greater,(25) Bayley-III cognitive composite score <85, bilateral blindness with no or some functional vision, or hearing impairment with or without amplification.

Neonatal morbidities in the NRN databases included intracranial hemorrhage (ICH), periventricular leukomalacia (PVL), bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) defined as respiratory support at 36 weeks’ PMA, BPD severity grade,(26) necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC), and retinopathy of prematurity (ROP). ICH was classified by Papile criteria with severe hemorrhage defined as grade III or IV.(27) For the current study, severe ROP was defined as ROP stage ≥3 or the presence of plus disease.

Statistical Analyses

Demographic, perinatal, and discharge characteristics and 18–26 months’ corrected age outcomes were compared between SDOH groups using chi-square tests for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables. Only children with data available for all three SDOH variables analyzed were included. There was no data imputation. Regression analyses were conducted to compare outcomes by individual SDOH factors and the total number of risk-associated SDOH at birth. Generalized linear mixed effect models were used to compute adjusted odds ratios or mean differences of outcomes (as applicable) for each of the individual SDOH factors. Models included center as a random effect and controlled for perinatal characteristics, neonatal morbidity, and maternal ethnicity. The neonatal morbidity variable included sepsis (early- or late-onset), brain injury (ICH grade III/IV or PVL), NEC, and ROP stage ≥3 or plus disease. Models of Bayley-III language composite scores also controlled for the household’s primary language while models of readmission also controlled for corrected age at follow-up. To identify which SDOH was associated with the greatest risk, comparisons by individual SDOH controlled for the two remaining SDOH factors (e.g., comparisons by education level were adjusted for race and insurance status). Finally, we counted the individual SDOH for a total number of SDOH and fit similar generalized mixed effect regression models of outcomes, controlling for perinatal characteristics, neonatal morbidity, and maternal ethnicity. We did not correct for multiple comparisons as many analyses were hypothesis-generating in nature.

Results

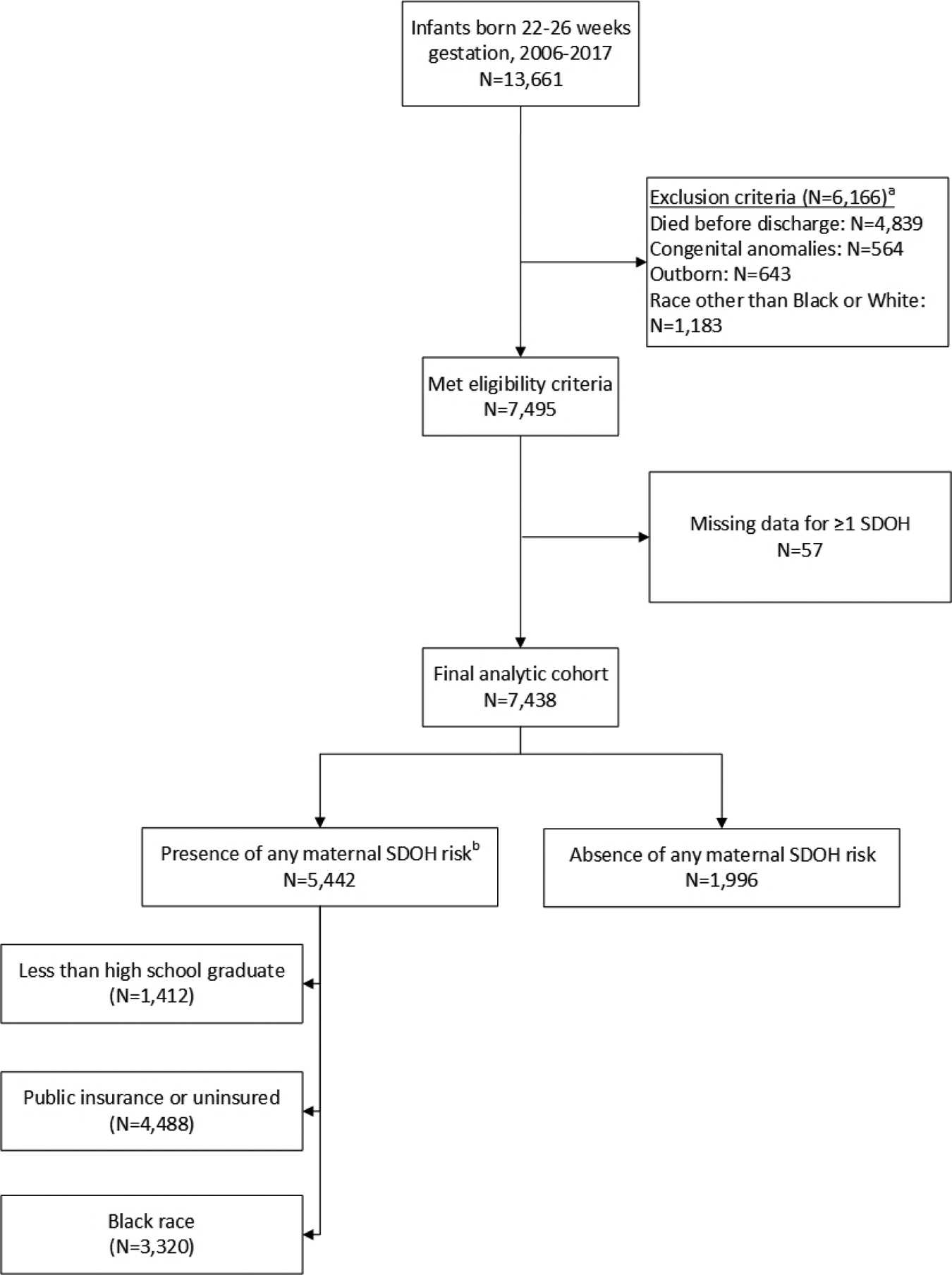

Of the 7438 children who met inclusion criteria, 5442 (73%) had at least one SDOH associated with disadvantage (Figure 1; available at www.jpeds.com). Mothers with any risk-associated SDOH were younger at delivery (27 years vs. 30 years, p<0.001), less likely to be married (32% vs. 82%, p<0.001), and less likely to receive antenatal steroids (89% vs. 95%, p<0.001) (Table 1). In addition, mothers with public/no insurance and mothers who identified as Black were more likely to be diagnosed with histological chorioamnionitis (insurance: 59% vs. 54%, p<0.001; race: 61% vs. 54%, p<0.001) but less likely to undergo cesarean section (insurance: 64% vs. 66%, p=0.011; race: 62% vs. 67%, p<0.001) compared with mothers with private insurance and mothers who identified as White. For neonatal morbidities, infants whose mothers had public/no insurance and those who identified as Black had a higher incidence of late-onset sepsis and NEC but a lower incidence of BPD than those without these risk-associated SDOH (Table 1).

Figure 1 (Online).

Flow diagram showing subject classification by the presence or absence of maternal social determinants of health associated with risk. a. More than one exclusion criterion may be present. b. SDOH, social determinant(s) of health; more than one risk-associated social determinant of health may be present.

Table 1.

Maternal and neonatal characteristics and morbidities by social determinants of health at birth

| Characteristic† | Education | Insurance | Race | Any SDH Risk Factor | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <High school grad | ≥High school grad | Public or None | Private | Black | White | Yes | No | |

| Maternal | ||||||||

| Age (years) | 24.9 (6.9)*** | 28.4 (5.9) | 26.2 (6.0)*** | 30.2 (5.8) | 27.1 (6.2)*** | 28.3 (6.3) | 26.8 (6.3)*** | 30.4 (5.5) |

| Married | 344/1405 (24)*** | 2850/5991 (48) | 1057/4460 (24)*** | 2137/2936 (73) | 779/3297 (24)*** | 2415/4099 (59) | 1546/5405 (29)*** | 1648/1991 (83) |

| Diabetes (insulin-dependent) | 59/1411 (4) | 262/6024 (4) | 197/4486 (4) | 124/2949 (4) | 159/3319 (5) | 162/4116 (4) | 247/5439 (5) | 74/1996 (4) |

| Hypertension | 296/1411 (21)* | 1430/6023 (24) | 1017/4487 (23) | 709/2947 (24) | 890/3319 (27)*** | 836/4115 (20) | 1286/5440 (24) | 440/1994 (22) |

| Histological chorioamnionitis | 699/1237 (57) | 3075/5368 (57) | 2365/4018 (59)*** | 1409/2587 (54) | 1818/2960 (61)*** | 1956/3645 (54) | 2878/4857 (59)*** | 896/1748 (51) |

| Antenatal steroids | 1207/1410 (86)*** | 5523/6017 (92) | 3954/4483 (88)*** | 2776/2944 (94) | 2953/3314 (89)*** | 3777/4113 (92) | 4831/5434 (89)*** | 1899/1993 (95) |

| Multiple gestation | 246/1412 (17)*** | 1598/6026 (27) | 890/4488 (20)*** | 954/2950 (32) | 679/3320 (20)*** | 1165/4118 (28) | 1082/5442 (20)*** | 762/1996 (38) |

| Cesarean delivery | 886/1412 (63) | 3926/6024 (65) | 2852/4486 (64)* | 1960/2950 (66) | 2064/3318 (62)*** | 2748/4118 (67) | 3435/5440 (63)*** | 1377/1996 (69) |

| Neonatal | ||||||||

| Male | 693/1412 (49) | 3008/6022 (50) | 2201/4487 (49) | 1500/2947 (51) | 1581/3320 (48)** | 2120/4114 (52) | 2675/5441 (49) | 1026/1993 (51) |

| Gestational age (weeks) | 25.0 (1.0) | 24.9 (1.0) | 24.9 (1.0) | 24.9 (1.0) | 24.9 (1.1)*** | 25.0 (1.0) | 24.9 (1.0) | 25.0 (1.0) |

| Birth weight (grams) | 769 (157)** | 755 (160) | 755 (157)* | 762 (162) | 741 (155)*** | 772 (162) | 753 (157)*** | 770 (164) |

| Small for gestational age‡ | 62/1412 (4)* | 354/6022 (6) | 232/4487 (5)* | 184/2947 (6) | 192/3320 (6) | 224/4114 (5) | 291/5441 (5) | 125/1993 (6) |

| Early-onset sepsis | 32/1412 (2) | 132/6025 (2) | 93/4487 (2) | 71/2950 (2) | 56/3320 (2)** | 108/4117 (3) | 112/5441 (2) | 52/1996 (3) |

| Late-onset sepsis | 446/1411 (32) | 1802/6025 (30) | 1406/4486 (31)* | 842/2950 (29) | 1050/3320 (32)* | 1198/4116 (29) | 1689/5440 (31)* | 559/1996 (28) |

| Grade III/IV intracranial hemorrhage or PVL€ | 253/1405 (18) | 1047/6002 (17) | 776/4469 (17) | 524/2938 (18) | 561/3307 (17) | 739/4100 (18) | 952/5420 (18) | 348/1987 (18) |

| Bronchopulmonary dysplasia§ | 809/1403 (58)* | 3636/6004 (61) | 2612/4471 (58)** | 1833/2936 (62) | 1775/3301 (54)*** | 2670/4106 (65) | 3105/5416 (57)*** | 1340/1991 (67) |

| BPD severity¥ | ||||||||

| No BPD | 191/714 (27)* | 957/3579 (27) | 745/2665 (28) | 403/1628 (25) | 637/1978 (32)*** | 511/2315 (22) | 911/3158 (29)*** | 237/1135 (21) |

| Grade 1 BPD | 310/714 (43) | 1348/3579 (38) | 1006/2665 (38) | 652/1628 (40) | 694/1978 (35) | 964/2315 (42) | 1182/3158 (37) | 476/1135 (42) |

| Grade 2 BPD | 160/714 (22) | 923/3579 (26) | 666/2665 (25) | 417/1628 (26) | 442/1978 (22) | 641/2315 (28) | 766/3158 (24) | 317/1135 (28) |

| Grade 3 BPD | 53/714 (7) | 351/3579 (10) | 248/2665 (9) | 156/1628 (10) | 205/1978 (10) | 199/2315 (9) | 299/3158 (10) | 105/1135 (9) |

| Necrotizing enterocolitis | 150/1412 (11) | 553/6022 (9) | 467/4486 (10)** | 236/2948 (8) | 348/3319 (10)** | 355/4115 (9) | 555/5440 (10)*** | 148/1994 (7) |

| ROP (any stage)¤ | 1014/1393 (73) | 4347/5952 (73) | 3175/4435 (72)** | 2186/2910 (75) | 2215/3287 (67)*** | 3146/4058 (78) | 3820/5379 (71)*** | 1541/1966 (78) |

| ROP stage 3 or worse/plus disease | 346/1393 (25) | 1357/5952 (23) | 1020/4435 (23) | 683/2910 (23) | 641/3287 (20)*** | 1062/4058 (26) | 1182/5379 (22)*** | 521/1966 (27) |

P < 0.05

P < 0.01

P < 0.001

Values are n/N (%) for categorical variables and mean (SD) for continuous variables.

Small for gestational age defined as <10th percentile based on Alexander growth curves.

PVL, periventricular leukomalacia.

Bronchopulmonary dysplasia defined as respiratory support at 36 weeks.

BPD, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, severity available for infants born April 1, 2011 or later.

ROP, retinopathy of prematurity.

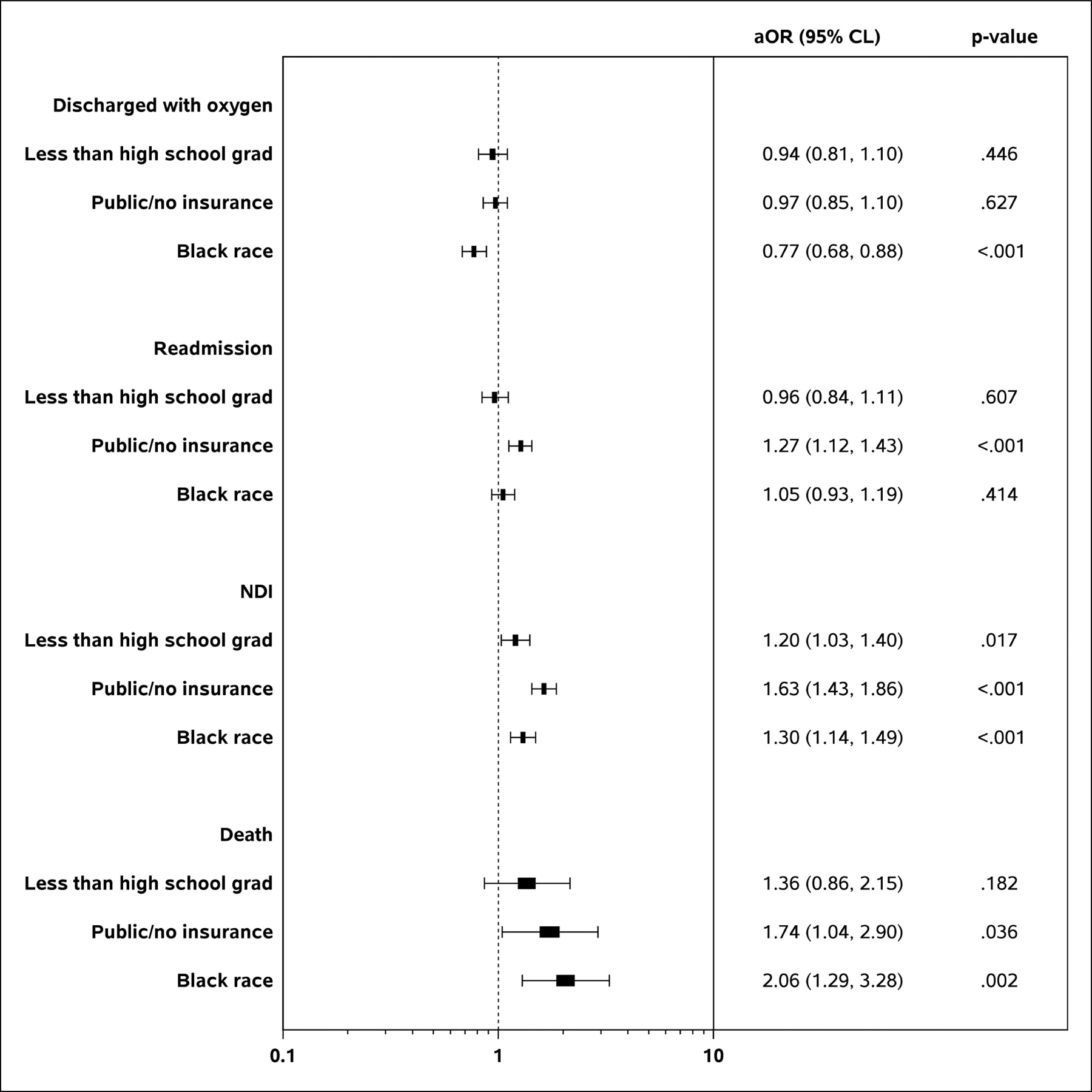

PMA at discharge did not vary by SDOH in unadjusted analyses (Table 2; available at www.jpeds.com). In adjusted analyses, infants whose mothers had public/no insurance were discharged at an older PMA compared with those whose mothers had private insurance (Table 3). There was no difference in PMA at discharge by maternal education level or race. While infants whose mothers had public/no insurance were more likely to be in the highest quartile PMA at discharge, infants whose mothers identified as Black were more likely to be in the lowest quartile PMA at discharge. Following the pattern of BPD, infants whose mothers identified as Black were less likely to be discharged with oxygen compared with infants whose mothers identified as White (aOR 0.77, 95% CI 0.68–0.88) (Figure 2). Growth parameter Z-scores at discharge did not vary by SDOH (Table 3).

Table 2 (Online).

Discharge characteristics by social determinants of health at birth

| Characteristic† | Education | Insurance | Race | Any SDH Risk Factor | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <High school grad | ≥High school grad | Public or None | Private | Black | White | Yes | No | |

| Discharge | ||||||||

| Postmenstrual age (weeks) | 42.0 (5.8) | 42.1 (6.1) | 42.2 (6.2) | 42.0 (5.7) | 42.0 (6.5) | 42.1 (5.6) | 42.1 (6.2) | 42.0 (5.5) |

| Discharged with oxygen | 455/1356 (34)*** | 2246/5747 (39) | 1558/4275 (36)** | 1143/2828 (40) | 1067/3180 (34)*** | 1634/3923 (42) | 1864/5193 (36)*** | 837/1910 (44) |

| Weight Z-score‡ | −0.7 (1.2)* | −0.8 (1.3) | −0.7 (1.2)** | −0.8 (1.3) | −0.9 (1.3)*** | −0.7 (1.2) | −0.8 (1.3) | −0.7 (1.3) |

| Length Z-score‡ | −1.8 (1.8)* | −2.0 (1.9) | −2.0 (1.9) | −1.9 (1.8) | −2.1 (2.0)*** | −1.8 (1.8) | −2.0 (1.9)** | −1.8 (1.8) |

| Head circumference Z-score‡ | −0.9 (1.7) | −0.9 (1.7) | −0.9 (1.7) | −0.9 (1.7) | −1.0 (1.7)** | −0.9 (1.7) | −0.9 (1.7) | −0.9 (1.7) |

| Readmission | ||||||||

| Readmission by 18–26 months’ corrected | 637/1245 (51) | 2639/5356 (49) | 2075/3919 (53)*** | 1201/2682 (45) | 1519/2950 (51)** | 1757/3651 (48) | 2471/4786 (52)*** | 805/1815 (44) |

| Number of readmissions | 1.2 (1.9) | 1.1 (1.9) | 1.3 (2.0)*** | 0.9 (1.6) | 1.2 (1.8)* | 1.1 (1.9) | 1.2 (1.9)*** | 0.9 (1.7) |

P < 0.05

P < 0.01

P < 0.001

Values are n/N (%) for categorical variables and mean (SD) for continuous variables.

Weight, length, and head circumference Z-scores at discharge are based on INTERGROWTH-21st standards.

Table 3.

Regression analyses of outcomes by social determinants of health at birth

| Outcome | Education (<High school grad vs. ≥High school grad) | Insurance (Public/None vs. Private) | Race (Black vs. White) |

|---|---|---|---|

| aOR or aMD† (95% CL) | aOR or aMD† (95% CL) | aOR or aMD† (95% CL) | |

| Discharge | |||

| Postmenstrual age (weeks) | 0.09 (−0.27, 0.45) | 0.37 (0.06, 0.68)* | −0.28 (−0.60, 0.03) |

| Postmenstrual age in lowest quartile | 0.96 (0.81, 1.12) | 0.96 (0.84, 1.10) | 1.60 (1.39, 1.85)*** |

| Postmenstrual age in highest quartile | 1.10 (0.93, 1.29) | 1.22 (1.06, 1.41)** | 0.87 (0.76, 1.01) |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | 0.54 (−1.97, 3.05) | 2.74 (0.59, 4.88)* | −2.00 (−4.19, 0.20) |

| Discharged with oxygen | 0.94 (0.81, 1.10) | 0.97 (0.85, 1.10) | 0.77 (0.68, 0.88)*** |

| Weight Z-score‡ | 0.04 (−0.03, 0.11) | 0.02 (−0.04, 0.09) | 0.00 (−0.06, 0.07) |

| Length Z-score‡ | 0.10 (−0.01, 0.21) | −0.11 (−0.21, −0.02)* | −0.08 (−0.18, 0.02) |

| OFC Z-score‡ | 0.06 (−0.05, 0.16) | −0.07 (−0.16, 0.02) | 0.03 (−0.06, 0.13) |

| Follow-up | |||

| NDI€ | 1.20 (1.03, 1.40)* | 1.63 (1.43, 1.86)*** | 1.30 (1.14, 1.49)*** |

| Death (post-discharge) | 1.36 (0.86, 2.15) | 1.74 (1.04, 2.90)* | 2.06 (1.29, 3.28)** |

| Readmission by 18–26 months’ corrected age | 0.96 (0.84, 1.11) | 1.27 (1.12, 1.43)*** | 1.05 (0.93, 1.19) |

| Bayley-III cognitive composite score | −1.63 (−2.62, −0.64)** | −4.07 (−4.91, −3.23)*** | −2.75 (−3.61, −1.88)*** |

| Bayley-III language composite score | −2.16 (−3.30, −1.03)*** | −4.50 (−5.46, −3.55)*** | −4.10 (−5.09, −3.12)*** |

| Bayley-III motor composite score | −1.49 (−2.68, −0.30)* | −3.11 (−4.11, −2.11)*** | 1.19 (0.17, 2.21)* |

| Bayley-III cognitive composite <70 | 1.11 (0.89, 1.38) | 1.31 (1.08, 1.59)** | 1.02 (0.84, 1.24) |

| Bayley-III cognitive composite <85 | 1.21 (1.04, 1.40)* | 1.69 (1.47, 1.93)*** | 1.37 (1.19, 1.57)*** |

| Moderate or severe cerebral palsy | 0.95 (0.72, 1.25) | 1.03 (0.81, 1.30) | 0.93 (0.74, 1.18) |

| GMFCS level ≥2§ | 0.96 (0.75, 1.23) | 1.06 (0.86, 1.30) | 0.76 (0.62, 0.94)* |

| Weight Z-score¥ | −0.03 (−0.11, 0.04) | −0.07 (−0.13, 0.00)* | 0.29 (0.22, 0.35)*** |

| Length Z-score¥ | −0.15 (−0.24, −0.06)** | −0.15 (−0.22, −0.07)*** | 0.33 (0.25, 0.41)*** |

| OFC Z-score¥ | −0.14 (−0.24, −0.04)** | −0.15 (−0.24, −0.06)** | 0.07 (−0.01, 0.16) |

P < 0.05

P < 0.01

P < 0.001

Adjusted odds ratios (aOR) are calculated for categorical variables and adjusted mean differences (aMD) are calculated for continuous variables. Odds ratios and mean differences are adjusted for the following variables: center, Hispanic origin, maternal age, diabetes (insulin-dependent), hypertension, clinical chorioamnionitis, multiple gestation, Cesarean delivery, birth year, infant sex, gestational age, small-for-gestational age, and neonatal morbidity (sepsis (early or late), IVH grade 3–4/PVL, proven NEC, and ROP stage 3 or greater/plus disease). Comparisons by individual SDH (i.e., less than high school graduate, no or public insurance, non-white race) control for the two remaining SDH factors (e.g., comparisons by education level were adjusted for race and insurance status). Models of readmission also controlled for corrected age at follow-up. Models of Bayley-III language composite scores also controlled for primary language.

Weight, length, and head circumference Z-scores at discharge are based on INTERGROWTH-21st standards.

NDI, neurodevelopmental impairment, defined as any of the following: moderate or severe cerebral palsy, gross motor function classification system level 2 or greater, Bayley-III cognitive composite score <85, bilateral blindness with no or some functional vision, or hearing impairment with or without amplification

GMFCS, gross motor function classification system.

Weight, length, and head circumference Z-scores at follow-up are based on WHO child growth.

Figure 2.

Forest plots of the regression analyses for highlighted categorical outcomes by social determinants of health at birth.

The overall follow-up rate for children who survived to discharge was 89% (6620/7438). For children exposed to maternal risk-associated SDOH, the follow-up rate was 88% (4798/5442), while for unexposed children, the follow-rate was higher at 91% (1822/1996, p<0.001). While the follow-up rate varied by maternal insurance status (public/no insurance 88% vs. private insurance 91%, p<0.001), the follow-up rate did not vary by education level (88% vs. 89%, p=0.311) or race (89% vs. 89%, p=0.874).

Readmission prior to follow-up was more common among infants whose mothers had public/no insurance compared with those whose mothers had private insurance (aOR 1.27, 95% CI 1.12–1.43) (Table 3). At follow-up, children exposed to either risk-associated education level or insurance status had lower length and head circumference Z-scores compared with unexposed children (Table 4; available at www.jpeds.com). In contrast, weight and length Z-scores were higher for infants with Black mothers compared with those with White mothers (Table 4; available at www.jpeds.com). Unadjusted analyses identified a higher incidence in NDI (41% vs. 26%, p<0.001) and in death post-discharge (2% vs. 1%, p<0.001) among those with any risk-associated SDOH exposure compared with those with no exposure (Table 4; available at www.jpeds.com). In regression analyses, NDI remained more common among children exposed to each risk-associated SDOH compared with those unexposed (less than high school graduate: aOR 1.20 95% CL 1.03, 1.40; public/no insurance: aOR 1.63 95% CL 1.43, 1.86; Black race: aOR 1.30, 95% CL 1.14, 1.49) (Figure 2). Death post-discharge also remained significantly more common among Black children compared with White children (aOR 2.06, 95% CL 1.29, 3.28).

Table 4 (Online).

Neurological and sensory outcomes at 18–26 months’ corrected age by social determinants of health at birth

| Characteristic† | Education | Insurance | Race | Any SDH Risk Factor | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <High school grad | ≥High school grad | Public or None | Private | Black | White | Yes | No | |

| Survival and NDI ‡ | ||||||||

| NDI‡ | 519/1213 (43)*** | 1841/5192 (35) | 1611/3803 (42)*** | 749/2602 (29) | 1189/2861 (42)*** | 1171/3544 (33) | 1904/4643 (41)*** | 456/1762 (26) |

| Death (post-discharge) | 34/1410 (2)** | 85/6015 (1) | 94/4479 (2)*** | 25/2946 (1) | 79/3314 (2)*** | 40/4111 (1) | 105/5432 (2)*** | 14/1993 (1) |

| Bayley-III Scales | ||||||||

| Cognitive composite score | 84.4 (14.1)*** | 87.4 (15.8) | 84.6 (14.6)*** | 90.2 (16.2) | 84.7 (14.7)*** | 88.6 (15.9) | 84.9 (14.8)*** | 91.9 (16.3) |

| Language composite score | 78.7 (15.3)*** | 83.5 (17.7) | 79.9 (16.1)*** | 86.6 (18.3) | 80.3 (16.1)*** | 84.5 (18.1) | 80.2 (16.2)*** | 89.0 (18.6) |

| Motor composite, score€ | 84.3 (15.9)* | 85.7 (16.9) | 84.3 (16.5)*** | 87.2 (16.9) | 85.3 (16.6) | 85.6 (16.8) | 84.7 (16.6)*** | 87.6 (16.9) |

| Neurological Exam | ||||||||

| Moderate or severe cerebral palsy | 86/1239 (7) | 400/5308 (8) | 295/3898 (8) | 191/2649 (7) | 224/2935 (8) | 262/3612 (7) | 367/4758 (8) | 119/1789 (7) |

| Gross motor function level ≥2 | 112/1237 (9) | 523/5303 (10) | 382/3892 (10) | 253/2648 (10) | 274/2931 (9) | 361/3609 (10) | 470/4750 (10) | 165/1790 (9) |

| Bilateral blindness | 13/1239 (1) | 78/5308 (1) | 47/3896 (1) | 44/2651 (2) | 31/2934 (1)* | 60/3613 (2) | 59/4757 (1) | 32/1790 (2) |

| Bilateral hearing impairment | 45/1230 (4) | 142/5279 (3) | 120/3870 (3) | 67/2639 (3) | 94/2915 (3) | 93/3594 (3) | 147/4726 (3) | 40/1783 (2) |

| Follow-up Growth | ||||||||

| Weight Z-score§ | −0.3 (1.1) | −0.3 (1.1) | −0.3 (1.2) | −0.4 (1.1) | −0.2 (1.2)*** | −0.4 (1.1) | −0.3 (1.2)*** | −0.4 (1.1) |

| Length Z-score§ | −0.9 (1.5)** | −0.8 (1.3) | −0.8 (1.4)* | −0.7 (1.2) | −0.7 (1.4)*** | −0.9 (1.3) | −0.8 (1.4) | −0.8 (1.2) |

| OFC Z-score§ | −0.5 (1.7)*** | −0.3 (1.5) | −0.4 (1.6)*** | −0.2 (1.5) | −0.3 (1.5) | −0.3 (1.6) | −0.4 (1.6)*** | −0.2 (1.5) |

P < 0.05

P < 0.01

P < 0.001

Values are n/N (%) for categorical variables and mean (SD) for continuous variables.

NDI, neurodevelopmental impairment, defined as any of the following: moderate or severe cerebral palsy, gross motor function classification system level 2 or greater, Bayley-III cognitive composite score <85, bilateral blindness with no or some functional vision, or hearing impairment with or without amplification

Bayley-III motor composite score consistently available beginning January 1, 2010.

Weight, length, and orbitofrontal circumference (OFC) Z-scores at follow-up are based on WHO child growth charts.

Thirty percent of the cohort (2233/7438) were exposed to one risk-associated SDOH analyzed, while 35% (2640/7438) were exposed to two risk-associated SDOH analyzed and 8% (569/7438) were affected by all three risk-associated SDOH analyzed. In unadjusted analyses, infants with a greater number of risk-associated SDOH at birth were more likely to be discharged at a PMA in the lowest quartile, less likely to be discharged with supplemental oxygen, and more likely to be readmitted by 18–26 months’ corrected age (Table 5; available at www.jpeds.com). In adjusted analyses, the higher likelihood for discharge PMA in the lowest quartile and lower likelihood for discharge with oxygen persisted for those with 2 vs. 0, 3 vs. 0, 2 vs. 1, and 3 vs. 1 riskassociated SDOH while readmission occurred more frequently for those with 1 or 2 risk-associated SDOH vs. 0 risk-associated SDOH (Table 6).

Table 5 (Online).

Outcomes by number of risk-associated social determinants of health at birth

| Number of Risk-Associated Social Determinants of Health at Birth | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (N=1996) | 1 (N=2233) | 2 (N=2640) | 3 (N=569) | p-value | |

| Categorical Outcome, n (%) | |||||

| Discharge | |||||

| Postmenstrual age in lowest quartile | 442/1912 (23) | 526/2126 (25) | 737/2523 (29) | 178/549 (32) | <0.001 |

| Postmenstrual age in highest quartile | 458/1912 (24) | 540/2126 (25) | 640/2523 (25) | 136/549 (25) | 0.686 |

| Discharged with oxygen | 837/1910 (44) | 820/2124 (39) | 872/2520 (35) | 172/549 (31) | <0.001 |

| Follow-Up | |||||

| NDIa | 456/1762 (26) | 695/1893 (37) | 1003/2266 (44) | 206/484 (43) | <0.001 |

| Death (post-discharge) | 14/1993 (1) | 27/2229 (1) | 54/2635 (2) | 24/568 (4) | <0.001 |

| Readmission by 18–26 months’ corrected age | 805/1815 (44) | 967/1954 (49) | 1248/2336 (53) | 256/496 (52) | <0.001 |

| Bayley-III cognitive composite <70 | 161/1755 (9) | 251/1886 (13) | 309/2258 (14) | 57/482 (12) | <0.001 |

| Bayley-III cognitive composite <85 | 406/1755 (23) | 644/1886 (34) | 946/2258 (42) | 195/482 (40) | <0.001 |

| Moderate or severe cerebral palsy | 119/1789 (7) | 166/1938 (9) | 164/2326 (7) | 37/494 (7) | 0.127 |

| GMFCS level ≥2b | 165/1790 (9) | 217/1934 (11) | 208/2322 (9) | 45/494 (9) | 0.065 |

| Continuous Outcome, mean (SD) | |||||

| Discharge | |||||

| Postmenstrual age (weeks) | 42.0 (5.5) | 42.2 (6.0) | 42.1 (6.3) | 41.8 (6.3) | 0.479 |

| Weight Z-scorec | −0.7 (1.3) | −0.8 (1.3) | −0.8 (1.2) | −0.8 (1.3) | 0.824 |

| Length Z-scorec | −1.8 (1.8) | −2.0 (1.9) | −2.0 (1.9) | −2.0 (2.0) | 0.037 |

| Head circumference Z-scorec | −0.9 (1.7) | −0.9 (1.8) | −1.0 (1.7) | −0.9 (1.7) | 0.190 |

| Follow-up | |||||

| Bayley-III cognitive composite score | 91.9 (16.3) | 86.2 (15.4) | 84.0 (14.3) | 84.5 (14.3) | <0.001 |

| Bayley-III language composite score | 89.0 (18.6) | 81.6 (17.0) | 79.1 (15.5) | 79.9 (15.9) | <0.001 |

| Bayley-III motor composite scored | 87.5 (16.9) | 84.8 (17.0) | 84.6 (16.3) | 85.0 (16.2) | <0.001 |

| Weight Z-scoree | −0.4 (1.1) | −0.3 (1.2) | −0.3 (1.2) | −0.3 (1.1) | <0.001 |

| Length Z-scoree | −0.8 (1.2) | −0.8 (1.4) | −0.7 (1.3) | −0.9 (1.7) | 0.227 |

| Head circumference Z-scoree | −0.2 (1.5) | −0.3 (1.5) | −0.4 (1.6) | −0.4 (1.5) | <0.001 |

NDI, neurodevelopmental impairment, defined as one or more of the following: moderate or severe cerebral palsy, gross motor function classification system level 2 or greater, Bayley-III cognitive composite score <85, bilateral blindness with no or some functional vision, or hearing impairment with or without amplification.

GMFCS, gross motor function classification system.

Weight, length, and head circumference Z-scores at discharge are based on INTERGROWTH-21st standards.

Bayley-III motor composite score consistently available beginning January 1, 2010.

Weight, length, and head circumference Z-scores at follow-up are based on WHO child growth charts.

Table 6.

Regression analyses of outcomes by number of risk-associated social determinants of health at birth

| Outcome | Number of Risk-Associated Social Determinants of Health at Birth | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 vs. 0 | 2 vs. 0 | 3 vs. 0 | 2 vs. 1 | 3 vs. 1 | 3 vs. 2 | |

| aOR or aMD† (95% CL) | aOR or aMD† (95% CL) | aOR or aMD† (95% CL) | aOR or aMD† (95% CL) | aOR or aMD† (95% CL) | aOR or aMD† (95% CL) | |

| Discharge | ||||||

| Postmenstrual age (PMA, weeks) | 0.36 (0.01, 0.72)* | 0.21 (−0.15, 0.57) | 0.29 (−0.27, 0.85) | −0.15 (−0.48, 0.17) | −0.07 (−0.61, 0.46) | 0.08 (−0.43, 0.60) |

| PMA in lowest quartile | 1.03 (0.87, 1.22) | 1.34 (1.14, 1.59)*** | 1.32 (1.03, 1.69)* | 1.30 (1.13, 1.51)*** | 1.28 (1.02, 1.62)* | 0.98 (0.79, 1.23) |

| PMA in highest quartile | 1.15 (0.98, 1.36) | 1.12 (0.95, 1.32) | 1.24 (0.96, 1.60) | 0.97 (0.84, 1.12) | 1.08 (0.85, 1.37) | 1.11 (0.88, 1.40) |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | 2.63 (0.16, 5.09)* | 1.58 (−0.93, 4.09) | 2.00 (−1.91, 5.91) | −1.05 (−3.31, 1.21) | −0.63 (−4.34, 3.08) | 0.42 (−3.16, 4.00) |

| Discharged with oxygen | 0.91 (0.78, 1.06) | 0.79 (0.68, 0.92)** | 0.70 (0.55, 0.90)** | 0.87 (0.75, 0.99)* | 0.77 (0.62, 0.97)* | 0.89 (0.72, 1.11) |

| Weight Z-score‡ | −0.03 (−0.10, 0.04) | 0.02 (−0.05, 0.10) | 0.06 (−0.05, 0.18) | 0.06 (−0.01, 0.12) | 0.09 (−0.01, 0.20) | 0.04 (−0.06, 0.14) |

| Length Z-score‡ | −0.21 (−0.32, −0.10)*** | −0.15 (−0.27, −0.04)** | −0.16 (−0.34, 0.02) | 0.06 (−0.05, 0.16) | 0.05 (−0.12, 0.22) | −0.01 (−0.17, 0.15) |

| OFC Z-score‡ | −0.08 (−0.19, 0.03) | −0.06 (−0.17, 0.05) | 0.03 (−0.14, 0.20) | 0.02 (−0.07, 0.12) | 0.11 (−0.05, 0.27) | 0.09 (−0.06, 0.24) |

| Follow-up | ||||||

| NDI€ | 1.74 (1.49, 2.03)*** | 2.28 (1.95, 2.66)*** | 2.36 (1.86, 3.00)*** | 1.31 (1.14, 1.50)*** | 1.36 (1.09, 1.70)** | 1.04 (0.84, 1.28) |

| Death (postdischarge) | 1.65 (0.85, 3.21) | 2.57 (1.38, 4.78)** | 5.22 (2.54, 10.73)*** | 1.55 (0.96, 2.50) | 3.16 (1.76, 5.67)*** | 2.03 (1.23, 3.37)** |

| Readmission by 18–26 mo. corrected | 1.20 (1.05, 1.38)* | 1.34 (1.17, 1.54)*** | 1.21 (0.97, 1.50) | 1.12 (0.99, 1.27) | 1.00 (0.82, 1.24) | 0.90 (0.73, 1.10) |

| Bayley-III cognitive composite score | −5.70 (−6.66, −4.73)*** | −7.48 (−8.46, −6.50)*** | −7.79 (−9.33, −6.26)*** | −1.78 (−2.67, −0.90)*** | −2.10 (−3.56, −0.63)** | −0.31 (−1.72, 1.09) |

| Bayley-III language composite score | −7.36 (−8.46, −6.27)*** | −9.33 (−10.46, −8.21)*** | −9.70 (−11.44, −7.96)*** | −1.97 (−2.98, −0.96)*** | −2.34 (−4.00, −0.68)** | −0.37 (−1.97, 1.23) |

| Bayley-III motor composite score§ | −3.29 (−4.44, −2.14)*** | −3.05 (−4.21, −1.88)*** | −3.06 (−4.93, −1.18)** | 0.25 (−0.81, 1.30) | 0.23 (−1.56, 2.02) | −0.01 (−1.73, 1.71) |

| Bayley-III cognitive composite <70 | 1.61 (1.28, 2.02)*** | 1.56 (1.24, 1.97)*** | 1.48 (1.03, 2.11)* | 0.97 (0.80, 1.18) | 0.92 (0.66, 1.28) | 0.94 (0.69, 1.30) |

| Bayley-III cognitive composite <85 | 1.82 (1.55, 2.14)*** | 2.44 (2.08, 2.87)*** | 2.61 (2.05, 3.33)*** | 1.34 (1.17, 1.54)*** | 1.43 (1.14, 1.79)** | 1.07 (0.86, 1.32) |

| Moderate or severe cerebral palsy | 1.31 (1.01, 1.70)* | 0.97 (0.74, 1.28) | 1.10 (0.72, 1.68) | 0.74 (0.58, 0.94)* | 0.84 (0.57, 1.25) | 1.13 (0.77, 1.67) |

| GMFCS level >2 | 1.22 (0.97, 1.54) | 0.86 (0.67, 1.10) | 0.91 (0.62, 1.34) | 0.70 (0.57, 0.87)** | 0.74 (0.52, 1.07) | 1.06 (0.74, 1.51) |

| Weight Z-score¥ | 0.09 (0.02, 0.16)* | 0.15 (0.07, 0.23)*** | 0.18 (0.06, 0.30)** | 0.06 (−0.01, 0.13) | 0.09 (−0.02, 0.20) | 0.03 (−0.08, 0.14) |

| Length Z-score¥ | 0.01 (−0.08, 0.10) | 0.08 (−0.01, 0.17) | −0.03 (−0.17, 0.11) | 0.07 (−0.01, 0.15) | −0.04 (−0.17, 0.10) | −0.11 (−0.24, 0.02) |

| OFC Z-score¥ | −0.10 (−0.20, 0.00) | −0.14 (−0.24, −0.04)** | −0.22 (−0.38, −0.06)** | −0.04 (−0.13, 0.05) | −0.12 (−0.28, 0.03) | −0.08 (−0.23, 0.07) |

P < 0.05

P < 0.01

P < 0.001

Adjusted odds ratios (aOR) calculated for categorical variables and adjusted mean differences (aMD) calculated for continuous variables. Odds ratios and mean differences are adjusted for the following variables: center, maternal age, diabetes (insulin-dependent), hypertension, clinical chorioamnionitis, multiple gestation, Cesarean delivery, birth year, infant sex, gestational age, small-for-gestational age, and neonatal morbidity (sepsis (early or late), ICH grade 3–4/PVL, proven NEC, and ROP stage 3 or greater/plus disease). Analyses of readmission also control for corrected age at follow-up. Models of Bayley-III language composite scores also controlled for primary language. Regression models for comparisons of outcomes by race (non-white vs. white) also control for Hispanic origin.

Weight, length, and head circumference Z-scores at discharge are based on INTERGROWTH-21st standards.

NDI, neurodevelopmental impairment, defined as any of the following: moderate or severe cerebral palsy, gross motor function classification system level 2 or greater, Bayley-III cognitive composite score <85, bilateral blindness with no or some functional vision, or hearing impairment with or without amplification

The motor domain was administered beginning in January 2010.

Weight, length, and orbitofrontal circumference (OFC) Z-scores at follow-up are based on WHO child growth.

With respect to growth parameters, children with risk-associated SDOH had a greater weight Z-score and a lower head circumference Z-score at follow-up compared with those with no risk-associated SDOH (Table 6). NDI at 18–26 months’ corrected age occurred more frequently with increasing number of risk-associated SDOH for nearly all comparisons. Lastly, death post-discharge was five times as likely for those with 3 vs. 0 risk-associated SDOH (aOR 5.22, 95% CL 2.54, 10.73) and twice as likely for those with 3 vs. 2 risk-associated SDOH (aOR 2.03, 95% CL 1.23, 3.37).

Discussion

Extremely preterm birth is an established risk factor for death and altered neurodevelopment among survivors. Children affected by extremely preterm birth frequently have preexisting risk-associated SDOH relevant to infancy and early childhood outcomes. In the current cohort, PMA at discharge varied by maternal insurance status, such that infants of mothers with public/no insurance had longer hospitalizations than infants of mothers with private insurance. At 18–26 months’ corrected age, NDI was more common among children who were exposed to any of the three risk-associated SDOH at birth compared with those without risk-associated SDOH exposure at birth. Death post-discharge was more common among children whose mothers had public/no insurance at birth or identified as Black compared with those whose mothers had private insurance at birth or identified as White. This study identifies children who may benefit from expanded support services at discharge due to their combination of preterm birth and sociodemographic risk.

In the United States, low-income women are less likely to have health insurance prior to pregnancy or may have insufficient coverage.(19) In the current study, there were differences in maternal perinatal care pertinent to children born extremely preterm, including less exposure to antenatal steroids for mothers with risk-associated education level, insurance status, or race as well as less frequent cesarean section for mothers with public/no insurance or non-White race. This is consistent with previously reported discrepancies in perinatal maternal interventions by SDOH. Within the Vermont Oxford Network, the rate of antenatal steroid administration for women threatening preterm delivery differed by race with a higher rate for White women compared with Black women.(7) The rate of cesarean section also was higher for White women than Black women.(15)

Infants born to mothers with risk-associated SDOH had a lower incidence of BPD compared with infants born to mothers without SDOH associated with disadvantage. Previously, a lower incidence of BPD among Black infants compared with White infants was found by the Prematurity and Respiratory Outcome Program investigators.(28) BPD is hindered by being defined pragmatically by a treatment, leaving it susceptible to unconscious bias. Infants with any risk-associated SDOH were less likely to be discharged with oxygen than those without such SDOH. The lower incidence of BPD may have been due to physiological differences, genetic differences,(29–31) or due to more aggressive weaning of respiratory support if discharge on supplemental oxygen seemed infeasible for a given family or home environment.

While growth Z-scores at discharge did not differ by risk-associated SDOH, growth Z-scores at follow-up varied by SDOH. Head circumference Z-score at follow-up decreased with increasing number of risk-associated SDOH, which fits with the pattern observed in Bayley-III measures. In contrast, weight Z-score at follow-up increased with increasing number of risk-associated SDOH. The latter pattern may reflect early underpinnings for childhood obesity, an epidemic that disproportionately affects those with socioeconomic disadvantage in the United States compared with those with socioeconomic security.(32, 33)

Beyond discharge, there may be discrepancies in high-risk infant follow-up program participation based on SDOH. In the current study, the follow-up rate differed by the presence of any maternal risk-associated SDOH at birth. The follow-up rate was lower for infants whose mothers had public/no insurance at time of birth while the follow-up rate did not differ by maternal education level or race. This differs from a California cohort where maternal identity as Black race was associated with reduced odds of referral to high-risk infant follow-up,(34) reduced odds of first visit attendance,(35) and reduced odds of second visit attendance.(36) Insurance type was associated with high-risk infant follow-up attendance, similar to the current study.(35, 36) While societal challenges of poverty and racism are daunting to address at a local level, there is evidence that programs to support families affected by social disadvantage can improve outcomes.(37–39) For example, in Rhode Island, a multi-disciplinary transition home program equipped with family resource specialists and social workers reduced emergency department visits, readmissions, and Medicaid spending.(40, 41)

Strengths of this study included the multicenter design, large sample size, and comprehensive neurodevelopmental follow-up at 18–26 months’ corrected age. This study also had limitations. First, only three SDOH were analyzed, and the SDOH at birth were identified by maternal history and records. Other SDOH variables may affect children born prematurely, including neighborhood of residence,(7) paternal characteristics, economic stability, food insecurity, and household preferred language, and ethnicity. SDOH pertinent to women and children may vary internationally, and the results found in this U.S. cohort may not apply to populations in other countries. We did not analyze ethnicity as an independent SDOH given the epidemiologic paradox affecting those who identify as Hispanic(23) but rather adjusted for ethnicity in the analyses. In one recent prospective cohort study of women, there were no differences in the composite maternal or neonatal adverse outcomes between Hispanic and non-Hispanic women, and neonatal morbidities were similar between ethnic groups.(42) In the Assessment of Perinatal EXcellence study, Hispanic term newborns were less likely to experience adverse perinatal outcomes than non-Hispanic newborns despite a high incidence of public/no insurance among mothers who identified as Hispanic.(21) Differences in preferred language and bilingual or multilingual household status, generational differences, and country of origin may contribute to the inconsistent findings in newborn outcomes in relation to ethnicity. Finally, this was a cohort study with many outcomes analyzed; the hypothesis-generating nature of the analyses merits notation.

Socioeconomic factors, such as maternal education and insurance status, and societal factors, such as systemic racism, are intertwined with the outcomes of children born extremely preterm. The duration of birth hospitalization may be prolonged for children whose mothers have public or no insurance compared with those with private insurance, which carries with it a financial and emotional burden. A comprehensive approach to improving outcomes of children born prematurely must include addressing the health of the mother and the environment beyond the neonatal intensive care unit and beyond the immediate perinatal period.(43, 44) To drive change for children born extremely preterm, preventive strategies must be broadened from individual-level interventions to incorporate family, system, and society-level interventions.(45)

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The National Institutes of Health, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), the National Center for Research Resources, and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences provided grant support for the Neonatal Research Network’s Generic Database and Follow-up Studies through cooperative agreements. While NICHD staff had input into the study design, conduct, analysis, and manuscript drafting, the comments and views of the authors do not necessarily represent the views of NICHD, the National Institutes of Health, the Department of Health and Human Services, or the U.S. Government.

Participating NRN sites collected data and transmitted it to RTI International, the data coordinating center (DCC) for the network, which stored, managed and analyzed the data for this study. On behalf of the NRN, RTI International had full access to all of the data in the study, and with the NRN Center Principal Investigators, takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

We are indebted to our medical and nursing colleagues and the infants and their parents who agreed to take part in this study. The following investigators, in addition to those listed as authors, participated in this study:

NRN Steering Committee Chairs: Alan H. Jobe, MD PhD, University of Cincinnati (2003–2006); Michael S. Caplan, MD, University of Chicago, Pritzker School of Medicine (2006–2011); Richard A. Polin, MD, Division of Neonatology, College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University, (2011-present).

Alpert Medical School of Brown University and Women & Infants Hospital of Rhode Island (UG1 HD27904) – Abbot R. Laptook, MD; Martin Keszler, MD; Angelita M. Hensman, PhD RNC-NIC; Barbara Alksninis, RNC PNP; Carmena Bishop; Robert T. Burke, MD MPH; Melinda Caskey, MD; Laurie Hoffman, MD; Katharine Johnson, MD; Mary Lenore Keszler, MD; Andrea M. Knoll; Vita Lamberson, MD; Teresa M. Leach, MEd CAES; Emilee Little, BSN RN; Elisabeth C. McGowan, MD; Bonnie E. Stephens, MD; Elisa Vieira, BSN RN; Lucille St. Pierre BS; Suzy Ventura; Victoria E. Watson, MS CAS.

Case Western Reserve University, Rainbow Babies & Children’s Hospital (UG1 HD21364) – Anna Maria Hibbs, MD MSCE; Michele C. Walsh, MD MS; Deanne E Wilson-Costello, MD; Nancy S. Newman, RN; Monika Bhola, MD; Allison H. Payne, MD MS; Bonnie S. Siner, RN; Gulgun Yalcinkaya, MD.

Children’s Mercy Hospital, University of Missouri Kansas City School of Medicine (UG1 HD68284) – William E. Truog, MD; Eugenia K. Pallotto, MD MSCE; Howard W. Kilbride, MD; Cheri Gauldin, RN BS CCRC; Anne Holmes, RN MSN MBA-HCM CCRC; Kathy Johnson, RN CCRC; Allison Scott, RNC-NIC BSN CCRC; Prabhu S. Parimi, MD; Lisa Gaetano, RN MSN.

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, University Hospital, and Good Samaritan Hospital (UG1 HD27853, UL1 TR77) – Brenda B. Poindexter, MD MS; Kurt Schibler, MD; Suhas G. Kallapur, MD; Edward F. Donovan, MD; Stephanie Merhar, MD MS; Cathy Grisby, BSN CCRC; Kimberly Yolton, PhD; Barbara Alexander, RN; Traci Beiersdorfer, RN BSN; Kate Bridges, MD; Tanya E. Cahill, RN BSN; Juanita Dudley, RN BSN; Estelle E. Fischer, MHSA MBA; Teresa L. Gratton, PA; Devan Hayes, BS; Jody Hessling, RN; Lenora D. Jackson, CRC; Kristin Kirker, CRC; Holly L. Mincey, RN BSN; Greg Muthig, BS; Sara Stacey, BA; Jean J. Steichen, MD; Stacey Tepe, BS; Julia Thompson, RN BSN; Sandra Wuertz, RN BSN CLC.

Duke University School of Medicine, University Hospital, University of North Carolina, Duke Regional Hospital, and WakeMed Health and Hospitals (UG1 HD40492, UL1 TR1117, UL1 TR1111) – C. Michael Cotten, MD MHS; Ronald N. Goldberg, MD; Ricki F. Goldstein, MD; William F. Malcolm, MD; Deesha Mago-Shah, MD; Patricia L. Ashley, MD PhD; Joanne Finkle, RN JD; Kathy J. Auten, MSHS; Kimberley A. Fisher, PhD FNP-BC IBCLC; Sandra Grimes, RN BSN; Kathryn E. Gustafson, PhD; Melody B. Lohmeyer, RN MSN; Matthew M. Laughon, MD MPH; Carl L. Bose, MD; Janice Bernhardt, MS RN; Gennie Bose, RN; Cindy Clark, RN; Jennifer Talbert, MS RN; Diane Warner, MD MPH; Andrea Trembath, MD MPH; T. Michael O’Shea, MD MPH; Janice Wereszczak, CPNP-AC/PC; Stephen D. Kicklighter, MD; Ginger Rhodes-Ryan, ARNP MSN NNPBC; Donna White, BSN RN-BC.

Emory University, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, Grady Memorial Hospital, and Emory University Hospital Midtown (UG1 HD27851, UL1 TR454) – Ravi M. Patel, MD MSc; David P. Carlton, MD; Barbara J. Stoll, MD; Ellen C. Hale, RN BS CCRC; Yvonne C. Loggins, RN BSN; Ira Adams-Chapman, MD MPH (deceased); Ann Blackwelder, RN MN; Diane I. Bottcher, RN MSN; Sheena L. Carter, PhD; Salathiel Kendrick-Allwood, MD; Judith Laursen, RN; Maureen Mulligan LaRossa, RN; Colleen Mackie, BS RT; Amy Sanders, PsyD; Irma Seabrook, RRT; Gloria Smikle, PNP MSN; Lynn C. Wineski, RN MS.

Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development – Rosemary D. Higgins, MD; Andrew A. Bremer, MD PhD; Stephanie Wilson Archer, MA.

Indiana University, University Hospital, Methodist Hospital, Riley Hospital for Children, and Wishard Health Services (UG1 HD27856, UL1 TR6) – Gregory M. Sokol, MD; Brenda B. Poindexter, MD MS; Anna M. Dusick, MD FAAP (deceased); Lu Ann Papile, MD; Susan Gunn, NNP CCRC; Faithe Hamer, BS; Heidi M. Harmon, MD MS; Dianne E. Herron, RN CCRC; Abbey C. Hines, PsyD; Carolyn Lytle, MD MPH; Lucy C. Miller, RN BSN CCRC; Heike M. Minnich, PsyD HSPP; Leslie Richard, RN; Lucy Smiley, CCRC; Leslie Dawn Wilson, BSN CCRC.

McGovern Medical School at The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Children’s Memorial Hermann Hospital, Memorial Hermann Southwest Hospital, and Lyndon Baines Johnson General Hospital/Harris County Hospital District (UG1 HD87229, U10 HD21373) – Jon E. Tyson, MD MPH; Kathleen A. Kennedy, MD MPH; Amir M. Khan, MD; Barbara J. Stoll, MD; Andrea Duncan, MD, MS; Ricardo Mosquera, MD; Emily K. Stephens, BSN RNC-NIC; Georgia E. McDavid, RN; Nora I. Alaniz, BS; Elizabeth Allain, MS; Julie Arldt-McAlister, RN BSN; Katrina Burson, RN BSN; Allison G. Dempsey, PhD; Elizabeth Eason, MD; Patricia W. Evans, MD; Carmen Garcia, RN CCRP; Charles Green, PhD; Donna Hall, RN; Beverly Foley Harris, RN BSN; Margarita Jiminez, MD MPH; Janice John, CPNP; Patrick M. Jones, MD MA; M. Layne Lillie, RN BSN; Anna E. Lis, RN BSN; Karen Martin, RN; Sara C. Martin, RN BSN; Carrie M. Mason, MA LPA; Shannon McKee, EdS; Brenda H. Morris, MD; Kimberly Rennie, PhD; Shawna Rodgers, RN BSN; Saba Khan Siddiki, MD; Maegan C. Simmons, RN; Daniel Sperry, RN; Patti L. Pierce Tate, RCP; Sharon L. Wright, MT (ASCP).

Nationwide Children’s Hospital, The Abigail Wexner Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Center for Perinatal Research, The Ohio State University College of Medicine, The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center (U10 HD68278) – Pablo J. Sánchez, MD; Leif D. Nelin, MD; Sudarshan R. Jadcherla, MD; Jonathan L. Slaughter, MD, MPH; Keith O. Yeates, PhD, ABPP/CN; Sarah Keim, PhD, MA, MS; Nathalie L. Maitre, MD PhD; Christopher J. Timan, MD; Patricia Luzader, RN; Erna Clark, BA; Christine A. Fortney, PhD RN; Julie Gutentag, RN; Courtney Park, RN; Julie Shadd, BS, RD, LD; Margaret Sullivan, BA; Melanie Stein, BBA RRT; Mary Ann Nelin, MD; Julia Newton, MPH; Kristi Small, BS; Stephanie Burkhardt, BS, MPH; Jessica Purnell, BS, CCRC; Lindsay Pietruszewski, PT, DPT; Katelyn Levengood, PT, DPT; Nancy Batterson, OT/L, SCFES, CLC; Pamela Morehead, CRC; Helen Carey, PT, DHSc; Lina Yoseff-Salameh, MD; Rox Ann Sullivan, RN, BSN; Cole Hague, BA, MS; Jennifer Grothause, RN, BSN; Erin Fearns; Aubrey Fowler, BS; Jennifer Notestine, RN; Jill Tonneman, OTR/L, BCP; Krystal Hay, DPT; Margaret Sullivan, BS; Michelle Chao, BS; Kyrstin Warnimont, BS; Laura Marzec, MD; Bethany Miller, RN, BSN; Demi R. Beckford, MHS; Hallie Baugher, BS, MSN; Brittany DeSantis, BS; Cory Hanlon, BS; Jacqueline McCool.

RTI International (UG1 HD36790) – Abhik Das, PhD; Marie G. Gantz, PhD; Carla M. Bann, PhD; Dennis Wallace, PhD; Margaret M. Crawford, BS CCRP; Jenna Gabrio, MPH CCRP; David Leblond, BS; Jamie E. Newman, PhD MPH; Carolyn M. Petrie Huitema, MS CCRP; Jeanette O’Donnell Auman, BS; W. Kenneth Poole, PhD (deceased); Kristin M. Zaterka-Baxter, RN BSN CCRP.

Stanford University, Dominican Hospital, El Camino Hospital, and Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital (UG1 HD27880, UL1 TR93) – Krisa P. Van Meurs, MD; Valerie Y. Chock, MD MS Epi; David K. Stevenson, MD; Marian M. Adams, MD; M. Bethany Ball, BS CCRC; Barbara Bentley, PhD; Elizabeth Bruno, PhD; Alexis S. Davis, MD MS Epi; Maria Elena DeAnda, PhD; Anne M. DeBattista, RN PNP-C PhD; Lynne C. Huffman, MD; Magdy Ismael, MD MPH; Jean G. Kohn, MD MPH; Casey Krueger, PhD; Janice Lowe, MD; Ryan E. Lucash, PhD; Andrew W. Palmquist, RN BSN; Jessica Patel, PhD; Melinda S. Proud, RCP; Elizabeth N. Reichert, MA CCRC; Nicholas H. St. John, PhD; Dharshi Sivakumar, MD; Heather L. Taylor, PhD; Natalie Wager, PsyD; R. Jordan Williams, BA; Hali Weiss, MD.

Tufts Medical Center, Floating Hospital for Children (U10 HD53119) – Ivan D. Frantz III, MD; John M. Fiascone, MD; Elisabeth C. McGowan, MD; Brenda L. MacKinnon, RNC; Anne Furey, MPH; Ellen Nylen, RN BSN; Paige T. Church, MD; Cecelia E. Sibley, MHA PT; Ana K. Brussa MS OTR/L.

University of Alabama at Birmingham Health System and Children’s Hospital of Alabama (UG1 HD34216) – Waldemar A. Carlo, MD; Namasivayam Ambalavanan, MD; Myriam Peralta-Carcelen, MD MPH; Kathleen G. Nelson, MD; Kirstin J. Bailey, PhD; Fred J. Biasini, PhD (deceased); Stephanie A. Chopko, PhD; Monica V. Collins, RN BSN MaEd; Shirley S. Cosby, RN BSN; Kristen C. Johnston, MSN CRNP; Mary Beth Moses, PT MS PCS; Cryshelle S. Patterson, PhD; Vivien A. Phillips, RN BSN; Julie Preskitt, MSOT MPH; Richard V. Rector, PhD; Sally Whitley, MA OTR-L FAOTA.

University of California - Los Angeles, Mattel Children’s Hospital, Santa Monica Hospital, Los Robles Hospital and Medical Center, and Olive View Medical Center (UG1 HD68270) – Uday Devaskar, MD; Meena Garg, MD; Isabell B. Purdy, PhD CPNP; Teresa Chanlaw, MPH; Rachel Geller, RN BSN.

University of California – San Diego Medical Center and Sharp Mary Birch Hospital for Women and Newborns (U10 HD40461) – Neil N. Finer, MD; Yvonne E. Vaucher, MD MPH; David Kaegi, MD; Maynard R. Rasmussen, MD; Kathy Arnell, RNC; Clarence Demetrio, RN; Martha G. Fuller, PhD RN MSN; Wade Rich, BSHS RRT.

University of Iowa, Sanford Health, and Mercy Medical Center (UG1 HD53109, UL1 TR442) – Edward F. Bell, MD; Tarah T. Colaizy, MD MPH; John A. Widness, MD; Heidi M. Harmon, MD MS; Jane E. Brumbaugh, MD; Michael J. Acarregui, MD MBA; Karen J. Johnson, RN BSN; Diane L. Eastman, RN CPNP MA; Claire A. Goeke, RN; Mendi L. Schmelzel, MSN RN; Jacky R. Walker, RN; Michelle L. Baack, MD; Laurie A. Hogden, MD; Megan Broadbent, RN BSN; Chelsey Elenkiwich, RN BSN; Megan M. Henning, RN; Sarah Van Muyden, BSN RN; Dan L. Ellsbury, MD; Donia B. Campbell, RNC-NIC; Tracy L. Tud, RN.

University of Miami, Holtz Children’s Hospital (U10 HD21397, M01 RR16587) – Shahnaz Duara, MD; Charles R. Bauer, MD; Ruth Everett-Thomas, RN MSN; Sylvia Fajardo-Hiriart, MD; Arielle Rigaud, MD; Maria Calejo, MS; Silvia M. Frade Eguaras, MA; Michelle Harwood Berkowits, PhD; Andrea Garcia, MS; Helina Pierre, BA; Alexandra Stoerger, BA.

University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center (UG1 HD53089, UL1 TR41) – Kristi L. Watterberg, MD; Janell Fuller, MD; Robin K. Ohls, MD; Sandra Sundquist Beauman, MSN RNC-NIC; Conra Backstrom Lacy, RN; Andrea F. Duncan, MD MScr; Mary Hanson, RN BSN; Carol Hartenberger, MPH RN; Elizabeth Kuan, RN BSN; Jean R. Lowe, PhD; Rebecca A. Thomson, RN BSN.

University of Pennsylvania, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Pennsylvania Hospital, and Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (UG1 HD68244) – Sara B. DeMauro, MD MSCE; Eric C. Eichenwald, MD; Barbara Schmidt, MD MSc; Haresh Kirpalani, MB MSc; Aasma S. Chaudhary, BS RRT; Soraya Abbasi, MD; Toni Mancini, RN BSN CCRC; Christine Catts, CRNP; Noah Cook, MD; Dara M. Cucinotta, RN; Judy C. Bernbaum, MD; Marsha Gerdes, PhD; Sarvin Ghavam, MD; Hallam Hurt, MD; Jonathan Snyder, RN BSN RN; Saritha Vangala, RN MSN; Kristina Ziolkowski, CMA(AAMA) CCRP.

University of Rochester Medical Center, Golisano Children’s Hospital, and the University at Buffalo Women’s and Children’s Hospital of Buffalo (UG1 HD68263, U10 HD40521, UL1 TR42) – Carl T. D’Angio, MD; Dale L. Phelps, MD; Ronnie Guillet, MD PhD; Gary J. Myers, MD; Michelle Andrews-Hartley, MD; Julie Babish Johnson, MSW; Kyle Binion, BS; Melissa Bowman, RN NP; Elizabeth Boylin, BA; Erica Burnell, RN; Kelly R. Coleman, PsyD; Cait Fallone, MA; Osman Farooq, MD; Julianne Hunn, BS; Diane Hust, MS RN CS; Rosemary L. Jensen; Rachel Jones; Jennifer Kachelmeyer, BS; Emily Kushner, MA; Deanna Maffett, RN; Kimberly G. McKee, MPH; Joan Merzbach, LMSW; Gary J. Myers, MD; Constance Orme; Diane Prinzing; Linda J. Reubens, RN CCRC; Daisy Rochez, BS MHA; Mary Rowan, RN; Premini Sabaratnam, MPH; Ann Marie Scorsone, MS CCRC; Holly I.M. Wadkins, MA; Kelley Yost, PhD; Lauren Zwetsch, RN MS PNP; Satyan Lakshminrusimha, MD; Anne Marie Reynolds, MD MPH; Michael G. Sacilowski, MAT CCRC; Stephanie Guilford, BS; Emily Li, BA; Ashley Williams, MSEd; William A. Zorn, PhD.

University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas, Parkland Health & Hospital System, and Children’s Medical Center Dallas (UG1 HD40689) – Myra H. Wyckoff, MD; Luc P. Brion, MD; Pablo J. Sánchez, MD; Walid A. Salhab, MD; Charles R. Rosenfeld, MD; Roy J. Heyne, MD; Diana M. Vasil, MSN BSN RNC-NIC; Sally S. Adams, MS RN CPNP; Lijun Chen, PhD RN; Maria M. De Leon, RN BSN; Francis Eubanks, RN BSN; Alicia Guzman; Gaynelle Hensley, RN; Elizabeth T. Heyne, MS MA PA-C PsyD; Lizette E. Lee, RN; Melissa H. Leps, RN; Linda A. Madden, BSN RN CPNP; E. Rebecca McDougald, MSN APRN CPNP-PC/AC; Nancy A. Miller, RN; Janet S. Morgan, RN; Lara Pavageau, MD; Pollieanna Sepulveda, RN; Kristine Tolentino-Plata, MS; Cathy Twell Boatman, MS CIMI; Azucena Vera, AS; Jillian Waterbury DNP RN CPAP-PC.

University of Utah University Hospital, Intermountain Medical Center, McKay-Dee Hospital, Utah Valley Hospital, LDS Hospital, and Primary Children’s Medical Center (UG1 HD87226, U10 HD53124, UL1 RR25764) – Bradley A. Yoder, MD; Mariana Baserga, MD MSCI; Roger G. Faix, MD; Sarah Winter, MD; Stephen D. Minton, MD; Mark J. Sheffield, MD; Carrie A. Rau, RN BSN CCRC; Shawna Baker, RN; Karie Bird, RN BSN; Jill Burnett, RNC BSN; Susan Christensen, RNC BSN; Laura Cole-Bledsoe, RN; Brandy Davis, RN BSN; Jennifer O. Elmont, RN BSN; Jennifer J. Jensen, RN BSN; Manndi C. Loertscher, BS CCRP; Jamie Jordan, RN BSN; Trisha Marchant, RN BSN; Earl Maxson, BSN; Kandace M. McGrath, BS; Karen A. Osborne, RN BSN CCRC; D. Melody Parry, RN BSN; Brixen A. Reich, MSN RNC CCRC; Susan T. Schaefer, RRT RN BSN; Cynthia Spencer, RNC BSN; Michael Steffen, PhD; Katherine Tice, RN BSN; Kimberlee Weaver-Lewis, RN MS; Kathryn D. Woodbury, RN BSN; Karen Zanetti, RN.

Wake Forest University, Baptist Medical Center, Forsyth Medical Center, and Brenner Children’s Hospital (U10 HD40498, M01 RR7122) – T. Michael O’Shea, MD MPH; Robert G. Dillard, MD; Lisa K. Washburn, MD; Barbara G. Jackson, RN, BSN; Nancy Peters, RN; Korinne Chiu, MA; Deborah Evans Allred, MA LPA; Donald J. Goldstein, PhD; Raquel Halfond, MA; Carroll Peterson, MA; Ellen L. Waldrep, MS; Cherrie D. Welch, MD MPH; Melissa Whalen Morris, MA; Gail Wiley Hounshell, PhD.

Wayne State University, Hutzel Women’s Hospital, and Children’s Hospital of Michigan (UG1 HD21385) – Seetha Shankaran, MD; Beena G. Sood, MD MS; Girija Natarajan, MD; Athina Pappas, MD; Katherine Abramczyk; Prashant Agarwal, MD; Monika Bajaj, MD; Rebecca Bara, RN BSN; Elizabeth Billian, RN MBA; Sanjay Chawla, MD; Kirsten Childs, RN BSN; Lilia C. De Jesus, MD; Debra Driscoll, RN BSN; Melissa February, MD; Laura A. Goldston, MA; Mary E. Johnson, RN BSN; Geraldine Muran, RN BSN; Bogdan Panaitescu, MD; Jeannette E. Prentiss, MD; Diane White RT; Eunice Woldt, RN MSN; John Barks, MD; Stephanie A. Wiggins, MS; Mary K. Christensen, BA RRT; Martha D. Carlson, MD PhD.

Yale University, Yale-New Haven Children’s Hospital, and Bridgeport Hospital (U10 HD27871, UL1 TR142) – Richard A. Ehrenkranz, MD; Harris Jacobs, MD; Christine G. Butler, MD; Patricia Cervone, RN; Sheila Greisman, RN; Monica Konstantino, RN BSN; JoAnn Poulsen, RN; Janet Taft, RN BSN; Joanne Williams, RN BSN; Elaine Romano, MSN.

Funding

The National Institutes of Health, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), the National Center for Research Resources, and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences provided grant support for the Neonatal Research Network’s Generic Database and Follow-up Studies through cooperative agreements. Individual site grant numbers listed in the Acknowledgments.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Abbreviations

- aOR

Adjusted odds ratio

- Bayley-III

Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development, Third Edition

- BPD

Bronchopulmonary dysplasia

- ICH

Intracranial hemorrhage

- NDI

Neurodevelopmental impairment

- NICHD

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

- NEC

Necrotizing enterocolitis

- NRN

Neonatal Research Network

- PMA

Postmenstrual age

- PVL

Periventricular leukomalacia

- ROP

Retinopathy of prematurity

- SDOH

Social determinants of health

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Role of Funder

NICHD staff had input into the design and conduct of the study, interpretation of the data, and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Data were collected by participating centers. Data were managed and analyzed by RTI staff. The manuscript was prepared by the authors then reviewed and approved by NICHD staff.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures

The authors have no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

Data Sharing

Data reported in this paper may be requested through a data use agreement. Further details are available at https://neonatal.rti.org/index.cfm?fuseaction=DataRequest.Home.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Social determinants of health. Geneva: World Health Oragnization [cited 2021 June 12]. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1

- 2.Brumberg HL, Shah SI. Born early and born poor: An eco-bio-developmental model for poverty and preterm birth. J Neonatal Perinatal Med. 2015;8:179–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ruiz M, Goldblatt P, Morrison J, Kukla L, Svancara J, Riitta-Jarvelin M, et al. Mother’s education and the risk of preterm and small for gestational age birth: a DRIVERS meta-analysis of 12 European cohorts. J Epidemiol Commun H. 2015;69:826–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joseph RM, O’Shea TM, Allred EN, Heeren T, Kuban KK, Investigators ES. Maternal educational status at birth, maternal educational advancement, and neurocognitive outcomes at age 10 years among children born extremely preterm. Pediatr Res. 2018;83:767–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brandon GD, Adeniyi-Jones S, Kirkby S, Webb D, Culhane JF, Greenspan JS. Are outcomes and care processes for preterm neonates influenced by health insurance status? Pediatrics. 2009;124:122–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davey B, Sinha R, Lee JH, Gauthier M, Flores G. Social determinants of health and outcomes for children and adults with congenital heart disease: a systematic review. Pediatr Res. 2021;89:275–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horbar JD, Edwards EM, Greenberg LT, Profit J, Draper D, Helkey D, et al. Racial segregation and inequality in the neonatal intensive care unit for very low-birth-weight and very preterm infants. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173:455–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Profit J, Gould JB, Bennett M, Goldstein BA, Draper D, Phibbs CS, et al. Racial/ethnic disparity in NICU quality of care delivery. Pediatrics. 2017;140:e20170918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blair LM, Ford JL, Gugiu PC, Pickler RH, Munro CL, Anderson CM. Prediction of cognitive ability with social determinants in children of low birth weight. Nurs Res. 2020;69:427–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joseph RM, O’Shea TM, Allred EN, Heeren T, Kuban KK. Maternal educational status at birth, maternal educational advancement, and neurocognitive outcomes at age 10 years among children born extremely preterm. Pediatr Res. 2018;83:767–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim HJ, Min KB, Jung YJ, Min JY. Disparities in infant mortality by payment source for delivery in the United States. Prev Med. 2021;145:106361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harrell CJ, Burford TI, Cage BN, Nelson TM, Shearon S, Thompson A, et al. Multiple pathways linking racism to health outcomes. Du Bois Rev. 2011;8:143–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Howell EA, Egorova NN, Balbierz A, Zeitlin J, Hebert PL. Site of delivery contribution to black-white severe maternal morbidity disparity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215:143–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Janevic T, Zeitlin J, Auger N, Egorova NN, Hebert P, Balbierz A, et al. Association of race/ethnicity with very preterm neonatal morbidities. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172:1061–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boghossian NS, Geraci M, Lorch SA, Phibbs CS, Edwards EM, Horbar JD. Racial and ethnic differences over time in outcomes of infants born less than 30 weeks’ gestation. Pediatrics. 2019;144:e20191106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bishop-Royse J, Lange-Maia B, Murray L, Shah RC, DeMaio F. Structural racism, socioeconomic marginalization, and infant mortality. Public Health. 2021;190:55–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ely DM, Driscoll AK. Infant mortality in the United States, 2018: data from the period linked birth-infant death file. National Vital Statistics Reports. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fishman SH, Hummer RA, Sierra G, Hargrove T, Powers DA, Rogers RG. Race/ethnicity, maternal educational attainment, and infant mortality in the United States. Biodemography Soc Biol. 2020;66:1–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barfield WD. Social disadvantage and its effect on maternal and newborn health. Semin Perinatol. 2021;45:151407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petersen EE, Davis NL, Goodman D, Cox S, Syverson C, Seed K, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in pregnancy-related deaths - United States, 2007–2016. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report: MMWR. 2019;68:762–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parchem JG, Rice MM, Grobman WA, Bailit JL, Wapner RJ, Debbink MP, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in adverse perinatal outcomes at term. Am J Perinatol. 2023;40:557–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williams DR, Priest N, Anderson NB. Understanding associations among race, socioeconomic status, and health: patterns and prospects. Health Psychol. 2016;35:407–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Markides KS, Coreil J. The health of Hispanics in the southwestern United States: an epidemiologic paradox. Public Health Rep. 1986;101:253–65. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bayley NB Scales of Infant and Toddler Development, Third Edition. San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Assessment; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palisano R, Rosenbaum P, Walter S, Russell D, Wood E, Galuppi B. Development and reliability of a system to classify gross motor function in children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1997;39:214–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jensen EA, Dysart K, Gantz MG, McDonald S, Bamat NA, Keszler M, et al. The diagnosis of bronchopulmonary dysplasia in very preterm infants: an evidence-based approach. Am J Resp Crit Care. 2019;200:751–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Papile LA, Burstein J, Burstein R, Koffler H. Incidence and evolution of subependymal and intraventricular hemorrhage: a study of infants with birth weights less than 1,500 gm. J Pediatr. 1978;92:529–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ryan RM, Feng R, Bazacliu C, Ferkol TW, Ren CL, Mariani TJ, et al. Black race is associated with a lower risk of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. J Pediatr. 2019;207:130–5e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ambalavanan N, Cotten CM, Page GP, Carlo WA, Murray JC, Bhattacharya S, et al. Integrated genomic analyses in bronchopulmonary dysplasia. J Pediatr. 2015;166:531–7.e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li JJ, Yu KH, Oehlert J, Jeliffe-Pawlowski LL, Gould JB, Stevenson DK, et al. Exome sequencing of neonatal blood spots and the identification of genes implicated in bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192:589–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu KH, Li JJ, Snyder M, Shaw GM, O’Brodovich HM. The genetic predisposition to bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2016;28:318–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang YF. Cross-national comparison of childhood obesity: the epidemic and the relationship between obesity and socioeconomic status. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30:1129–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ogden CL LM, Carroll MD, Flegal KM. Obesity and socioeconomic status in children: United States 1988–1994 and 2005–2008. NCHS data brief no 51. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hintz SR, Gould JB, Bennett MV, Gray EE, Kagawa KJ, Schulman J, et al. Referral of very low birth weight infants to high-risk follow-up at neonatal intensive care unit discharge varies widely across California. J Pediatr. 2015;166:289–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hintz SR, Gould JB, Bennett MV, Lu TY, Gray EE, Jocson MAL, et al. Factors associated with successful first high-risk infant clinic visit for very low birth weight infants in California. J Pediatr. 2019;210:91–8e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fuller MG, Lu TY, Gray EE, Jocson MAL, Barger MK, Bennett M, et al. Rural residence and factors associated with attendance at the second high-risk infant follow-up clinic visit for very low birth weight infants in California. Am J Perinat. 2023;40:546–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee E, Greene R, Mitchell-Herzfeld S, DuMont K. Reducing low birth weight through home visitation response. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37:472–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kitzman HJ, Olds DL, Cole RE, Hanks CA, Anson EA, Arcoleo KJ, et al. Enduring effects of prenatal and infancy home visiting by nurses on children: follow-up of a randomized trial among children at age 12 years. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164:412–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaminski JW, Perou R, Visser SN, Scott KG, Beckwith L, Howard J, et al. Behavioral and socioemotional outcomes through age 5 years of the legacy for children public health approach to improving developmental outcomes among children born into poverty. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:1058–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu YY, McGowan E, Tucker R, Glasgow L, Kluckman M, Vohr B. Transition Home Plus program reduces Medicaid spending and health care use for high-risk infants admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit for 5 or more days. J Pediatr. 2018;200:91–7e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vohr B, McGowan E, Keszler L, O’Donnell M, Hawes K, Tucker R. Effects of a transition home program on preterm infant emergency room visits within 90 days of discharge. J Perinatol. 2018;38:185–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stafford IA, Turrentine MA, Ostovar-Kermani T, Moustafa ASZ, Berra A, Sangi-Haghpeykar H. Disparities between US Hispanic and non-Hispanic women in obesity-related perinatal outcomes: a prospective cohort study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2022;35:6172–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Beck AF, Edwards EM, Horbar JD, Howell EA, McCormick MC, Pursley DM. The color of health: how racism, segregation, and inequality affect the health and well-being of preterm infants and their families. Pediatr Res. 2020;87:227–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Horbar JD, Edwards EM, Ogbolu Y. Our responsibility to follow through for NICU infants and their families. Pediatrics. 2020;146:e20200360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Frieden TR. A framework for public health action: the health impact pyramid. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:590–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.