Abstract

Cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease (PD) severely affects patients’ prognosis, and early detection of patients at high risk of dementia conversion is important for establishing treatment strategies. We aimed to investigate whether multiparametric MRI radiomics from basal ganglia can improve the prediction of dementia development in PD when integrated with clinical profiles. In this retrospective study, 262 patients with newly diagnosed PD (June 2008–July 2017, follow-up >5 years) were included. MRI radiomic features (n = 1284) were extracted from bilateral caudate and putamen. Two models were developed to predict dementia development: (1) a clinical model—age, disease duration, and cognitive composite scores, and (2) a combined clinical and radiomics model. The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) were calculated for each model. The models’ interpretabilities were studied. Among total 262 PD patients (mean age, 68 years ± 8 [standard deviation]; 134 men), 51 (30.4%), and 24 (25.5%) patients developed dementia within 5 years of PD diagnosis in the training (n = 168) and test sets (n = 94), respectively. The combined model achieved superior predictive performance compared to the clinical model in training (AUCs 0.928 vs. 0.894, P = 0.284) and test set (AUCs 0.889 vs. 0.722, P = 0.016). The cognitive composite scores of the frontal/executive function domain contributed most to predicting dementia. Radiomics derived from the caudate were also highly associated with cognitive decline. Multiparametric MRI radiomics may have an incremental prognostic value when integrated with clinical profiles to predict future cognitive decline in PD.

Subject terms: Parkinson's disease, Parkinson's disease, Prognostic markers

Introduction

Cognitive impairment is a common non-motor symptom of Parkinson’s disease (PD), and approximately 80% of patients develop dementia within 20 years of diagnosis1. Dementia significantly affects the morbidity and mortality in PD, and early detection of patients at high risk of dementia conversion is important for proper implementation of therapeutic and supportive strategies2. Although the neurobiology underlying the cognitive decline in PD remains unclear, nigrostriatal degeneration is the core pathologic feature of PD3, and basal ganglia are likely to play a major role in the development of cognitive decline. Ample evidence suggests that dopamine deficiency in frontostriatal circuits is associated with early executive dysfunction in patients with PD4. In particular, the caudate has been proposed as a strong candidate associated with cognitive function in PD5. A recent study showed that a preferential dopamine loss in the anterior putamen was associated with a greater risk of developing PD with dementia (PDD)6. Further, several MRI studies have reported that structural7,8 and functional changes9 in the basal ganglia are associated with cognitive decline in PD.

Radiomics is an advanced technology extracting high-dimensional quantitative imaging features, such as intensity distributions, textural heterogeneity, and shape descriptors10. Radiomics aims to discover meaningful “hidden” information within radiological images, which is visually inaccessible to clinicians. The strength of radiomics is that it can reveal intralesional heterogeneity by quantification of texture information through mathematical extraction of the spatial distribution of signal intensities and pixel interrelationship11. In this study, we hypothesized that a combination of clinical information and radiomic features derived from MRI can help to accurately identify patients at a high risk of PDD. We investigated whether a multiparametric radiomics model of the basal ganglia (putamen and caudate) can improve the PDD prediction in patients with PD when integrated with clinical profiles.

Results

Clinical characteristics of patients with PD

The baseline clinical characteristics of the 262 patients with PD in the training set (n = 168) and test set (n = 94) are summarized in Table 1. In all, 51 (30.4%) and 24 (25.5%) patients developed PDD within 5 years of PD diagnosis in the training and test sets, respectively. In both training and test sets, patients who developed PDD within a defined time window were older, predominantly male, and had higher UPDRS-III scores compared with the characteristics of patients who did not develop PDD. The patients who developed PDD showed lower K-MMSE scores (P < 0.001) and lower composite scores for the visual memory/visuospatial function (P = 0.004 and 0.003, respectively), verbal memory function (P = 0.002 and 0.051, respectively), and frontal/executive function domains (P < 0.001) compared to those who did not develop PDD.

Table 1.

Baseline clinical characteristics of the study participants.

| Clinical variables | Training set (N = 168) | Test set (N = 94) | P valueb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No PDD | PDD | P valuea | No PDD | PDD | P valuea | ||

| n = 117 | n = 51 | n = 70 | n = 24 | ||||

| Age (years) | 66.2 ± 6.9 | 71.3 ± 7.5 | <0.001 | 66.6 ± 8.4 | 76.2 ± 6.1 | <0.001 | 0.212 |

| Onset age (years) | 64.9 ± 7.3 | 69.5 ± 7.9 | <0.001 | 64.8 ± 8.4 | 74.7 ± 5.8 | <0.001 | 0.295 |

| Female, no. (%) | 62 (53.0%) | 16 (31.4%) | 0.016 | 42 (60.0%) | 8 (33.3%) | 0.043 | 0.357 |

| Education (years) | 8.8 ± 4.5 | 9.9 ± 4.8 | 0.146 | 10.2 ± 3.9 | 7.3 ± 4.8 | 0.004 | 0.608 |

| Time from symptom onset to diagnosis (months) | 15.9 ± 14.0 | 22.0 ± 18.3 | 0.020 | 20.7 ± 19.2 | 18.0 ± 13.8 | 0.526 | 0.286 |

| UPDRS-III | 21.2 ± 10.2 | 25.1 ± 11.6 | 0.030 | 21.7 ± 8.7 | 25.6 ± 7.1 | 0.047 | 0.794 |

| Cognitive performance | |||||||

| K-MMSE (/30) | 27.3 ± 2.2 | 25.8 ± 2.7 | <0.001 | 27.2 ± 1.9 | 23.6 ± 3.1 | <0.001 | 0.096 |

| Visual memory/visuospatialc | 0.06 ± 0.90 | −0.43 ± 1.16 | 0.004 | 0.11 ± 0.81 | −0.47 ± 0.77 | 0.003 | 0.695 |

| Verbal memoryc | −0.01 ± 1.05 | −0.57 ± 1.00 | 0.002 | 0.19 ± 0.93 | −0.24 ± 0.94 | 0.051 | 0.044 |

| Frontal/executivec | 0.17 ± 1.03 | −0.85 ± 0.96 | <0.001 | 0.26 ± 0.91 | −0.85 ± 0.88 | <0.001 | 0.406 |

| Attention/working memory/languagec | 0.00 ± 1.17 | −0.01 ± 1.32 | 0.968 | −0.16 ± 0.84 | −0.57 ± 0.75 | 0.034 | 0.065 |

PD Parkinson’s disease, PDD Parkinson’s disease with dementia, UPDRS-III Unified PD Rating Scale Part III, K-MMSE the Korean version of the Mini-Mental State Examination.

Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation or number (percentage).

aComparisons between patients with PD who progressed to dementia within 5 years after the diagnosis of PD and those who did not develop dementia within 5 years.

bComparisons between the training and test sets.

cThe composite scores of each cognitive function domain were calculated according to the formula described in the previous work14.

The follow-up period was significantly longer in the training set compared to the test set (median 8.0 vs. 5.6 years, P = 0.012), which was expected as the training and test sets were allocated temporally. There were no significant differences between the training and test sets with regard to the age, sex, educational attainment, duration of PD, and the UPDRS-III scores. Cognitive performances were not significantly different between the training and test set, except for the verbal memory function.

Selected features and model performances

The multivariable regression analysis revealed that among clinical features, age and the composite scores of visuospatial/visual memory, verbal memory, and frontal/executive function domains had significant associations with dementia development, except the disease duration, without multi-collinearity. The detailed results are presented in Supplementary Table 1.

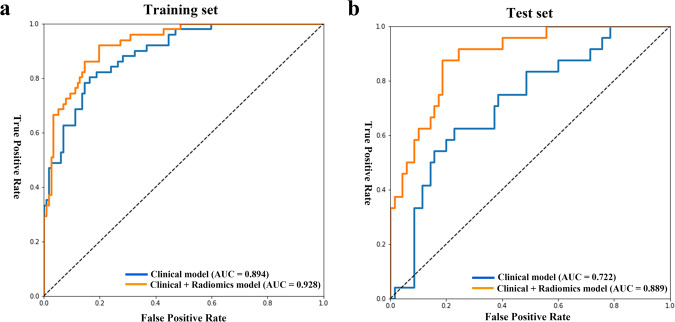

The performances of models for the prediction of PDD development in the training and test sets are provided in Table 2. In the training set, the clinical model showed an AUC, accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity of 0.894 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.845–0.943), 82.4%, 74.5%, and 85.5%, respectively. In the test set, the AUC, accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity were 0.722 (95% CI, 0.606–0.838), 73.4%, 58.3%, and 78.6%, respectively.

Table 2.

The performances of two models for prediction of PDD conversion in the training and test sets.

| AUC (95% CI) | Accuracy (%) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | P value | NRI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training set | ||||||

| Clinical model | 0.89 (0.85–0.94) | 82.4 | 74.5 | 85.5 | ||

| Clinical + Radiomics model | 0.93 (0.89–0.97) | 84.5 | 78.4 | 87.2 | 0.284 | 0.119 |

| Test set | ||||||

| Clinical model | 0.72 (0.61–0.84) | 73.4 | 58.3 | 78.6 | ||

| Clinical + Radiomics model | 0.89 (0.82–0.96) | 79.8 | 75.0 | 81.4 | 0.016 | 0.207 |

PDD Parkinson’s disease with dementia, AUC area under the curve, CI confidence interval, NRI net reclassification index.

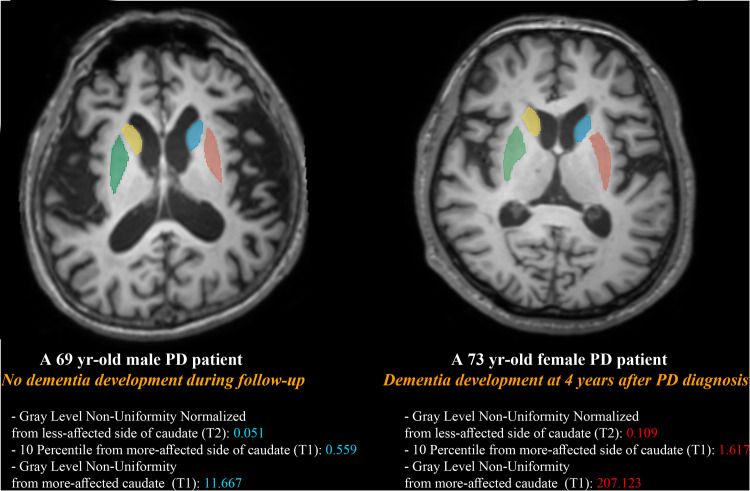

In the combined clinical and radiomics model, a total of eight features were selected: five clinical features (age, disease duration, composite scores of visuospatial/visual memory, verbal memory, and frontal/executive function domains) and three radiomic features (Gray-Level Non-Uniformity Normalized from the less-affected side of the caudate [GLRLM feature from T2], 10 Percentile from the more-affected side of the caudate [first-order feature from T1], and Gray Level Non-Uniformity from the more-affected caudate [GLDM feature from T1]). The results of Pearson correlation analysis between the selected radiomic features and clinical features are presented in Supplementary Table 2. The representative figures from two patients with and without dementia development with their values of selected radiomic features are provided in the Fig. 1. In the training set, the AUC, accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity were 0.928 (95% CI, 0.890–0.967), 84.5%, 78.4%, and 87.2%, respectively. In the test set, the AUC, accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity were 0.889 (95% CI, 0.820–0.959), 79.8%, 75.0%, and 81.4%, respectively.

Fig. 1. The representative figures from two patients with and without dementia development with their radiomic feature values.

Region of interests were drawn on both sides of caudate and putamen. A 69-year-old male who did not develop dementia during the follow-up period showed overall lower scores of selected three radiomic features compared to those from a 73-year-old female who develop dementia.

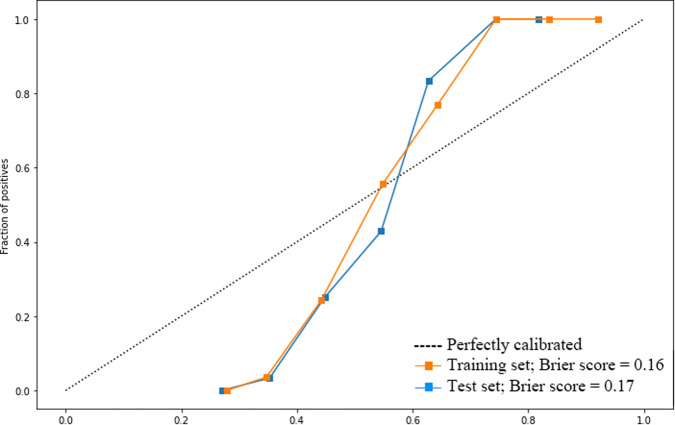

Calibration curves of the combined models were obtained (Fig. 2), demonstrating relatively good consistency between the estimated and actual probability of dementia conversion in both training and test sets. We also calculated the goodness of a predicted probability score with Brier score, which is between 0.0 and 1.0, where a model with perfect accuracy has a score of 0.0 and the worst has a score of 1.0. The Brier score was 0.16 and 0.17 in the training and test set, respectively.

Fig. 2. Calibration curves and Brier scores of the combined model (clinical + radiomic features) in both training and test sets.

The Brier score was 0.16 and 0.17 in the training and test set, respectively.

Comparison of model performances

In the training set, the combined clinical and radiomics model tended to show superior performance compared to that of the model with only clinical features (AUC: 0.928 vs. 0.894, P = 0.284, NRI = 0.119). In the test set, the performance of the combined clinical and radiomics model was superior to that of the clinical model (AUC: 0.889 vs. 0.722, P = 0.016, NRI = 0.207) (Table 2 and Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Receiver operating characteristics curves of the models in the training and test sets.

a In the training set, the combined clinical and radiomics model tended to show superior performance compared to that of the model with only clinical features (AUC: 0.928 vs. 0.894, P = 0.284, NRI = 0.119). b In the test set, the performance of the combined clinical and radiomics model was superior to that of the clinical model (AUC: 0.889 vs. 0.722, P = 0.016, NRI = 0.207). AUC area under the curve, NRI net reclassification index.

Model interpretability with SHAP

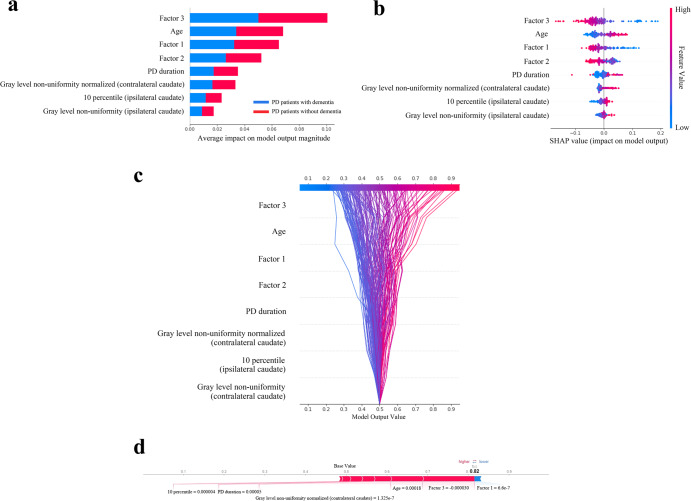

The SHAP values for each selected feature in the combined clinical and radiomics model were calculated, and the relevant plots are shown in Fig. 4. For each prediction, a positive SHAP value indicates an increase in the risk of developing PDD. The plots show that composite scores of the frontal/executive function domain were the most important risk factors, followed by age and composite scores of the visuospatial/visual memory and verbal memory function. Regarding the radiomic features, Gray Level Non-Uniformity Normalized from the less-affected side of the caudate [T2] was the highest contributing factor in predicting PDD.

Fig. 4. Model interpretability of the combined clinical and radiomics model for the prediction of dementia conversion with SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) in the training set.

a Variance importance plot listing the most significant variables. Features with greater importance for the prediction of dementia conversion are positioned in the upper portion, and the features are presented in descending order. b Summary plot of feature impact on the decision of the model showing positive and negative relationships of the predictors with the target variable. A positive SHAP value indicates an increase in the probability of dementia conversion. c Decision plot showing how the model predicts dementia conversion. Starting at the bottom of the plot, the prediction line shows how the SHAP values accumulate from the base value to arrive at the model’s final score at the top of the plot, demonstrating how each feature contributes to the overall prediction. d Force plot of a representative patient who developed dementia during the follow-up period. Red arrows represent features that drive the prediction value higher, while blue arrows represent features that drive the prediction value lower. The size of each arrow represents the magnitude of the effect of the corresponding feature. Note that factor 3 and age largely push the model prediction score higher. Factor 1 visual memory/visuospatial function, Factor 2 verbal memory function, Factor 3 frontal/executive function.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated whether the MRI radiomic features of the basal ganglia can improve the prediction of the development of dementia in patients with PD when integrated with a machine-learning classifier. As a result, several key clinical and radiomics features with significant association with PDD conversion were identified. We also found that the combined model of radiomics and clinical features achieved a superior performance for predicting PDD conversion compared to the clinical model (AUC 0.889 vs. 0.722 in the test set).

Cognitive impairment is commonly observed in patients with PD even at the early stages and can severely affect the quality of life and function, which necessitates identification of predictors of future cognitive decline in PD12. Several predictors have been proposed as markers for ongoing cognitive decline in PD, including age, genetic variation in APOE and MAPT, gait disturbance, motor assessments, non-motor symptoms, electroencephalogram analysis results, cognitive profiles, as well as several plasma biomarkers (e.g., α-synuclein/Aβ40, MIA, CRP, and albumin)13–16. In addition, several neuroimaging studies have shown that structural and functional integrity measured by MRI data can be a useful marker for early dementia conversion in patients with PD8,17–20. Our previous works also demonstrated that cortical thinning in the frontal areas and disrupted white matter connectivity in frontal and posterior cortical regions were associated with early dementia conversion in patients with PD18,20. However, so far, inconsistent results have been reported for both cortical thickness analyses and diffusion tensor imaging analyses, and there are no validated neuroimaging biomarkers yet. Radiomics, which enables mining of high-dimensional quantitative imaging features, has been frequently addressed in medical fields, specifically in the field of neurodegenerative diseases including PD. Numerous previous studies pointed out that radiomics can predict the diagnosis of PD21,22, motor handicap23, identify PD subtypes24, and predict PD progression assessed by Hoehn-Yahr Scale25. Therefore, based on this potential of radiomics, we hypothesized that radiomic features derived from classical MRI parameters may provide complementary information to predict PDD development. A few recent publications attempted to predict cognitive decline in PD with radiomics and suggested its prognostic role26,27, with applying radiomics to either T127 or quantitative susceptibility mapping26. In our study, multiparametric radiomic features from T1, T2, and FLAIR images were extracted for a relatively larger sample size, allowing for a more comprehensive analysis. Further, radiomic features were integrated with well-known clinical features to identify the added prognostic value of radiomics, which was also validated in an independent test set. Our results showed that multiparametric MRI radiomics, considered together with the clinical profile, has the potential to predict the development of dementia in patients with PD.

Among the selected features from the combined clinical and radiomics model, the Gray Level Non-Uniformity Normalized feature of GLRLM from the less-affected side of caudate, significantly contributed to the prediction of PDD conversion. The Gray Level Non-Uniformity feature measures the similarity of gray-level intensity values in an image, such that a higher value correlates with lesser similarity and greater heterogeneity28. Previous studies have reported that patients with PDD tend to exhibit iron deposition in the caudate29 and have a greater burden of cerebral microbleeds compared with patients without cognitive decline30. In addition, a higher severity in scoring of enlarged perivascular spaces in basal ganglia was associated with cognitive decline in PD8. Therefore, the frequently observed MRI findings in PD with cognitive decline may be attributed to the heterogeneity in the caudate, which might be captured by extracted radiomic features. Interestingly, the corresponding feature extracted from the less-affected side of the caudate rather than the more-affected side contributed the most to prediction of PDD conversion. Although the exact mechanism is unclear, much evidence has shown that the less-affected striatum also demonstrates considerable degree of degeneration, reduced endogenous dopamine, reduced dopamine uptake, and reduced fiber integrity, as assessed using PET, MR spectroscopy, and diffusion tensor imaging31. Further, the less-affected striatum appears to provide compensatory support to maintain the dopaminergic activity in the more-affected striatum, through crossed nigrostriatal pathways and alterations in subthalamic activity32. Therefore, the radiomic feature from the less-affected side of the caudate may provide clinically relevant information to predict PDD conversion.

In terms of the clinical variables, the frontal/executive function was the single most significant factor for the prediction of dementia. Several previous studies have attempted to identify neuropsychological predictors for PDD, yielding heterogeneous results. All cognitive domains, including the frontal/executive, visuospatial, memory, and language functions, have been associated with early PDD conversion2. A large community-based cohort study from the United Kingdom33, proposed that posterior cortical dysfunction, but not frontostriatal deficits, is a predictor for early dementia conversion in PD. Meanwhile, our previous works supported that the frontal/executive dysfunction would make a greater contribution to the development of PDD than dysfunction in other cognitive domains14,18,20. These discrepant findings likely reflect the marked clinical heterogeneity of PD14. The results of the present study are consistent with those of our previous works14,18,20, which highlighted the contribution of frontal/executive dysfunction to the early development of PDD, even when the radiomic features from the basal ganglia are additionally included as predictors. Although the exact mechanism remains to be elucidated, impairment of the frontal/executive function or frontal-subcortical pathways may further affect other cognitive domains through disruption of the reciprocal cortico-cortical connections or important nodes of information integration34.

In our study, we attempted to predict whether the patients develop dementia or not and performed classification analysis for the prediction of binary outcomes, rather survival analysis which predicts time to dementia development. Unlike determining the survival in cancer patients, the estimation of the time of dementia conversion in PD could be inaccurate, even though we made a great effort to determine whether patients progressed to dementia at every visit. Given that a considerable number of patients with PD eventually develop dementia and each patient enrolled in this study had a different follow-up period, we employed a 5-year time window for the determination of dementia development. The time from the diagnosis of PD to dementia conversion was treated as a categorical variable (i.e., whether a patient developed dementia within 5 years of PD diagnosis) in the model, rather than a continuous variable for the Cox proportional hazards model in the survival analysis. Indeed, in studies of patients with PD, binary classification tasks are frequently performed to predict dementia conversion20,35,36. Further, rather using a conventional statistical method such as binary logistic regression analysis, we applied machine-learning techniques in our study. Regression analysis is designed for relatively small datasets, and is not suitable when the number of features or variables exceeds the number of observations (i.e., high-dimensional datasets)37. Regression analysis can also be applied in the radiomics studies if appropriate feature selection methods can be preceded, however, we chose machine-learning techniques for the analysis as it is a more flexible alternative for analyzing high-dimensional, right-censored, and heterogeneous data37. Machine-learning techniques inherently handle high-dimensional data and have been adapted to handle censored data, therefore, can give more accurate results than traditional statistical methods when modeling high-dimensional data.

For the comparison of model performances, we used the two statistical methods: DeLong’s method and NRI. NRI was proposed either as an alternative or a supplement to C-index, as C-index has been criticized as being relatively insensitive to changes in absolute risk estimates and therefore having little power to detect modest but potentially meaningful differences between risk models38,39. Together with DeLong’s method, NRI is one of the widely used statistics for the assessment of the two models’ relative ability to discriminate between events and nonevents by quantifying the agreement between “upward” and “downward” risk reclassifications and event status40,41. In the training set, adding radiomics to the clinical model did not significantly enhance the model performance when the performances were compared with DeLong’s method. It may be attributed to the fact that the pure clinical model performed well enough with high AUC, comparable to that of the combined model, and the difference in AUCs was subtle. However, NRI proved the superiority of the combined clinical and radiomics model. In the test set, it was noteworthy that the combined model maintained a superior performance therefore. the AUCs of the clinical and the combined clinical and radiomics model exhibited a significant difference when assessed by both DeLong’s method and NRI. We believe that our study proved the added prognostic value of radiomics with adequate statistics and validation.

There are several limitations in our study. First, it was a single-center, retrospective study. Further studies with a larger dataset and external validation are needed to evaluate the generalizability of the models. Second, we used an automatic pipeline for brain segmentation (i.e., volBrain), which simply divided the basal ganglia into the putamen and caudate. More detailed segmentation of the striatum is needed to elucidate the association between other striatal sub-regions (e.g., anterior putamen and ventral striatum) and the risk for PDD conversion5,6.

In conclusion, we developed a model based on clinical and radiomic features to predict dementia conversion within 5 years of PD diagnosis. Its performance was superior to that of the model based only on clinical profiles. These findings suggest that clinical profiles and multiparametric MRI radiomics integrated with machine-learning classifiers may help predict future cognitive decline in patients with PD.

Methods

Participants

We retrospectively reviewed the Yonsei Parkinson Center database for medical records of 293 consecutive patients with newly diagnosed PD who first visited the outpatient clinic at Severance Hospital between June 2008 and July 2017. All the patients had been followed up for more than 3 years. PD was diagnosed according to the clinical diagnostic criteria of the United Kingdom PD Society Brain Bank42. All patients underwent brain MRI and detailed neuropsychological tests at the initial assessment. All subjects underwent a standardized neuropsychological battery called the Seoul Neuropsychological Screening Battery (SNSB) at initial assessment43. The SNSB covers five cognitive domains: attention and working memory (forward/backward digit span task and letter cancellation); language and related functions (the Korean version of the Boston Naming Test [K-BNT], calculation, and praxis); visuospatial function (the Rey Complex Figure Test [RCFT] copy), verbal and visual memory (immediate recall/delayed recall/recognition test using the Seoul Verbal Learning Test [SVLT] for verbal memory; immediate recall/delayed recall/recognition test using the RCFT for visual memory); and frontal/executive function (contrasting program and go/no-go test, the Controlled Oral Word Association Test [COWAT], and the Stroop test). To reduce the redundancy of neuropsychological subtests and the possibility of overrepresenting a single cognitive function domain, we first conducted a factor analysis based on age- and education-specific z-scores of 14 scorable subtests of the SNSB (forward digit span task, backward digit span task, K-BNT, RCFT copy, immediate recall, delayed recall, and recognition items using the SVLT and RCFT, COWAT for animal, COWAT for supermarket, COWAT for phonemic fluency, and the Stroop color reading test) to yield four cognitive function domains (visual memory/visuospatial [factor 1], verbal memory [factor 2], frontal/executive [factor 3], and attention/working memory/language [factor 4]) in patients with PD14. The calculating formula are as follows:

Visual memory/visuospatial function = 0.422 × RCFT (immediate recall) + 0.417 × RCFT (delayed recall) + 0.259 × RCFT copy + 0.179 × RCFT (recognition) − 0.033 × SVLT (delayed recall) − 0.098 × SVLT (recognition) − 0.056 × SVLT (immediate recall) − 0.096 × COWAT-semantic fluency [supermarket] − 0.048 × COWAT-semantic fluency [animal] − 0.026 × COWAT-phonemic fluency + 0.076 × Color Stroop test - 0.148 × Forward digit span − 0.072 × Backward digit span + 0.034 × K-BNT.

Verbal memory function = −0.016 × RCFT (immediate recall) − 0.014 × RCFT (delayed recall) − 0.138 × RCFT copy − 0.025 × RCFT (recognition) + 0.436 × SVLT (delayed recall) + 0.437 × SVLT (recognition) + 0.378 × SVLT (immediate recall) − 0.030 × COWAT-semantic fluency [supermarket] − 0.020 × COWAT-semantic fluency [animal] − 0.073 × COWAT-phonemic fluency − 0.090 × Color Stroop test − 0.043 × Forward digit span − 0.061 × Backward digit span − 0.001 × K-BNT.

Frontal/executive function = −0.054 × RCFT (immediate recall) − 0.034 × RCFT (delayed recall) + 0.058 × RCFT copy − 0.149 × RCFT (recognition) − 0.060 × SVLT (delayed recall) − 0.126 × SVLT (recognition) + 0.059 × SVLT (immediate recall) + 0.405 × COWAT-semantic fluency [supermarket] + 0.373 × COWAT-semantic fluency [animal] + 0.315 × COWAT-phonemic fluency + 0.305 × Color Stroop test − 0.111 × Forward digit span + 0.022 × Backward digit span + 0.017 × K-BNT.

Attention/working memory/language function = −0.156 × RCFT (immediate recall) − 0.163 × RCFT (delayed recall) + 0.026 × RCFT copy + 0.227 × RCFT (recognition) − 0.069 × SVLT (delayed recall) + 0.039 × SVLT (recognition) − 0.098 × SVLT (immediate recall) − 0.107 × COWAT-semantic fluency [supermarket] − 0.071 × COWAT-semantic fluency [animal] + 0.081 × COWAT-phonemic fluency − 0.055 × Color Stroop test + 0.593 × Forward digit span + 0.449 × Backward digit span + 0.233 × K-BNT.

Parkinsonian motor symptoms were assessed using the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale Part III (UPDRS-III), and the sum of the scores of the UPDRS-III items was calculated for each side of the body to identify the more-affected side.

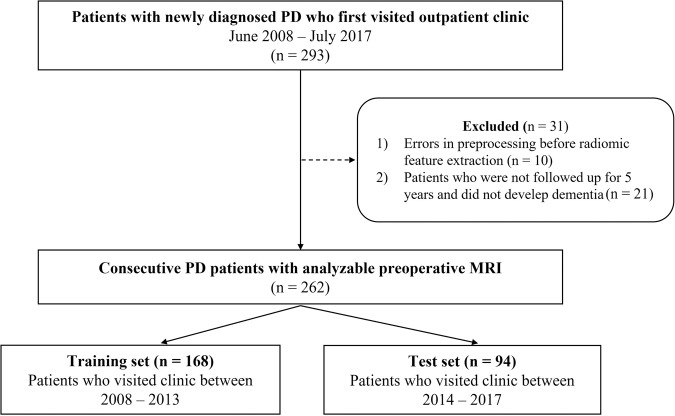

Among 293 patients, 21 (7.2%) patients were not followed up for the full 5 years and did not develop dementia until they were lost to follow-up. In addition, 10 patients were excluded from the study due to errors in the MRI dicom files, which resulted in failures of radiomic feature extraction. Thus, a total of 262 patients with PD were included in the final study population. Patients who visited the clinic between 2008 and 2013 were allocated to the training set (n = 168), and the patients who visited the clinic between 2014 and 2017 were allocated to the test set (n = 94) to perform external temporal validation (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Flowchart of patient enrollment.

Standard protocol approvals, registration, and patient consents

This study was approved by the Yonsei University Severance Hospital institutional review board (4-2022-0650), and the need for informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Assessment of dementia conversion

During the follow-up period, patients were diagnosed with PDD if they fulfilled the clinical criteria for probable PDD based on the Movement Disorder Society Task Force guidelines14,44. After diagnosis of PD, patients visited the outpatient clinic at 3-month intervals, and at every visit, they or their caregivers were asked questions regarding their daily functioning. Additionally, all patients underwent serial cognitive assessment using the Korean version of the Mini-Mental State Examination (K-MMSE) and Clock Drawing Test with a one-year interval (Level I tests)44. In case of definite cognitive decline or evidence of impairments in daily life due to cognitive changes (Level I45), most patients underwent the SNSB to identify the pattern of cognitive deficits and diagnose PDD at Level II44,46.

Since a considerable number of patients with PD eventually develop PDD1,47, a definitive time window is needed to determine whether the patient is at high risk of developing PDD18. A 5-year time window was employed based on previous studies14,20. Whether the patients developed PDD during the 5-year of follow-up period was investigated. Among the 262 patients with newly diagnosed PD, 75 patients had progressed to PDD within 5 years after the diagnosis of PD.

MRI protocols

All scans were acquired with a 3T scanner (Achieva; Philips Healthcare, Best, the Netherlands, or Ingenia CX; Philips Healthcare, Best, the Netherlands) with a 32-channel head coil. Head motion was minimized with restraining foam pads provided by the manufacturer. The MRI imaging protocol included T2-weighted images (repetition time [TR]/echo time [TE], 2800–3000/80–100 ms; field of view [FOV], 230–240 mm; section thickness, 5 mm; slice gap, 7 mm; matrix, 256 × 256), FLAIR (TR/TE, 9000–10,000/110–125 ms; FOV, 240 mm; section thickness, 5 mm; slice gap, 7 mm; matrix, 256 × 256), and noncontrast 3D T1-weighted images (TR/TE, 6.9/3.2 ms; FOV, 230–240 mm; section thickness, 1.2 mm; matrix, 256 × 256).

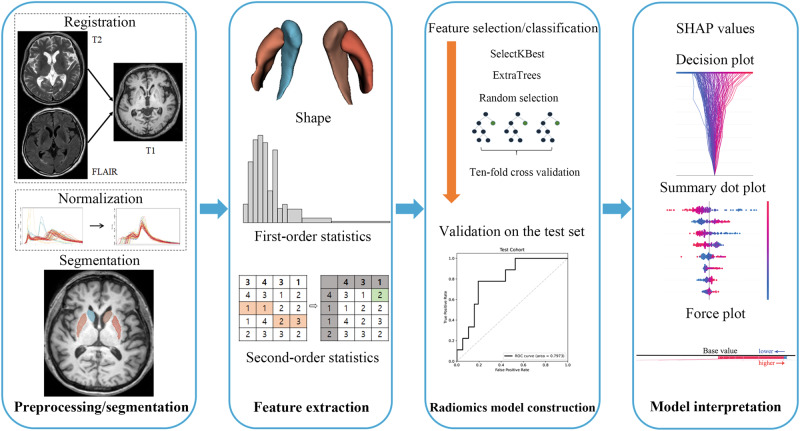

Image preprocessing and radiomic feature extraction

The detailed processes of image preprocessing and radiomic feature extraction are described in Fig. 6. Automated mask extraction of the basal ganglia, namely putamen and caudate, was performed using volBrain (https://volbrain.upv.es/)48, which is a robust automatic pipeline for brain segmentation with high accuracy49. Preprocessing of the images was performed to standardize the data analysis across patients. After removing unwanted low-frequency intensity non-uniformity by applying the N4 bias correction algorithm50, normalization of signal intensity was performed via z-score. All images were resampled to 1-mm isovoxels. T2 and FLAIR images were co-registered with T1 images by affine transformation with normalized mutual information as a cost function.

Fig. 6. Workflow of image preprocessing, radiomics feature extraction, and machine learning.

(1) Preprocessing and segmentation: For the radiomic feature extraction, registration of T2 and FLAIR to T1 images and normalization of signal intensities was performed. The regions of interest were put on the bilateral putamen and caudate. (2) Feature extraction: Three different categories of radiomic features—shape feature, first-order features, and second-order features were obtained. (3) Radiomics model construction: SelectKBest feature selection method combined with ExtraTrees classifier were used to develop two predictive models—clinical and combined (clinical + radiomics) model. The models were developed in the training set, then validated in the test set. (4) Model interpretation: We performed SHAP analysis to understand the contributing role of each selected radiomic feature and obtained decision plot, summary dot plot, and force plot.

After image preprocessing, radiomic feature extraction from bilateral caudate and putamen was performed using PyRadiomics (version 2.0)51, which conformed to the Image Biomarker Standardization Initiative52. Based on the more-affected side of each patient (either right or left), radiomic features from the more-affected caudate or putamen were distinguished from those of the less-affected caudate or putamen. The radiomic features included 14 shape features, 18 first-order features, and 75 second-order features [such as gray-level co-occurrence matrix (n = 24), gray-level run-length matrix (GLRLM, n = 16), gray-level size zone matrix (n = 16), gray-level dependence matrix (GLDM, n = 14), and neighboring gray tone difference matrix (n = 5)]. A total of 1284 (107 features × 2 sub-regions of the basal ganglia (caudate and putamen) × more-affected/less-affected side × 3 sequences) radiomic features were extracted.

Machine learning and model construction

Feature selection and machine-learning process were performed using Python 3 with the Scikit-Learn library module (version 0.21.2). Because the number of radiomic features was greater than the number of cases, the SelectKBest function in the Scikit-Learn module was used for feature selection according to the k highest scores53. Then, selected radiomic features were integrated with the ExtraTrees classifier to build a predictive model with ten-fold cross-validation. In the ten-fold cross-validation, the training set is split into 10 folds. A fold is used in each iteration once as testing data, while the remaining folds are used as training data54. The process is repetitive until all dataset is evaluated, and the cross-validation results in the average performance of the models.

Two types of models were trained as follows: (1) a clinical model—age, disease duration, cognitive composite scores of visual memory/visuospatial, verbal memory, and frontal/executive function domains, and (2) a combined model based on radiomics and clinical features. The clinical features to predict PDD conversion within 5 years of PD diagnosis were selected based on the Cox regression analysis results of our previous study14. The two models were developed from the training set and were validated in the test set. The multivariable regression analysis was performed in 262 PD patients to examine whether each clinical feature had independent and significant associations with the development of dementia. Pearson correlation analysis was performed between the selected radiomic features and clinical features to evaluate whether they have a significant correlation. The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity were obtained. Additionally, the calibration curves of the combined model (clinical and radiomic features) were plotted in both training and test sets to examine the models’ accuracy, together with Brier score. Calibration refers to the agreement between observed outcomes and predictions55. A calibration plot is the primary graphical method for evaluating calibration performance. A graphical assessment of calibration is possible with predictions on the x axis, and the outcome on the y axis. Perfect predictions should be on the 45° line. A slope close to 1 and an intercept close to 0 (i.e., the 45° line of the plot) indicates good calibration56. For linear regression, the calibration plot is a simple scatter plot. For binary outcomes, the plot contains only 0 and 1 values for the y axis57. Smoothing techniques can be used to estimate the observed probabilities of the outcome (p(y = 1)) in relation to the predicted probabilities.

The Brier score is not a measure of either discrimination performance or calibration performance alone, but a measure of overall performance, which incorporates both the discrimination and calibration aspects of a model that predicts binary outcomes58. Therefore, it is desirable to present both the Brier score and the calibration plot.

The Brier score is calculated as follows:

where n is the number of subjects, pi is the probability of event predicted by the model for the ith subject, and oi is the observed outcome in the ith subject (i.e., 1 for event or 0 for non-event)57. Therefore, a score closer to 0 indicates a better predictive performance.

The AUCs of those two models were compared by DeLong’s method59 and the net reclassification index (NRI)60. A NRI value greater than zero indicates superior performance of a new model over an old model. Multiple comparisons were corrected using a false-discovery rate approach, and a false-discovery rate-corrected P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analysis was performed using statistical software R (version 4.0.1; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Model interpretability with Shapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP)

SHAP was used to interpret and evaluate the significance of each radiomic feature from the radiomics model61. SHAP, originating from game theory, assesses the contribution of each variable of the model to its output61,62. The output of each possible combination of other variables is collected. SHAP analysis enables the quantification of continuous and categorical variables in the texture features only and the combined models. Features listed higher on the left vertical axis indicate a stronger influence on the overall model outcome. Feature values are color-coded: red data points indicate higher values, and blue data points indicate lower values63. In addition, this allows the quantification of the impact of each variable on the prediction, not only on a global level (on the overall population) but also locally (on a subset or one patient)64. Thus, Shapley values for each variable are additive, which makes the contribution of each variable convertible to a share of the output classification probability. This provides an intuitive visualization for clinicians using this model. SHAP measured the contribution of each feature of the model to the increase or decrease in the probability of PDD development within a 5-years’ time window.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2020R1I1A1A01071648 and NRF-2021R1I1A1A01059678) and faculty research grants of Yonsei University College of Medicine (6-2020-0157). This research was also supported by a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: HI21C1161).

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study’s conception and design. Material preparation and data collection were performed by C.J.P., Y.W.P., and S.J.C. The analysis was performed by J.E. and K.S.P. The first draft of the manuscript was written by C.J.P., Y.J.K., S.S.A., and S.-K.L. The manuscript revision was made by J.K., P.H.L., Y.H.S., and S.-K.L. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

All data and codes used for this study is available from the corresponding author on request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Yae Won Park, Seok Jong Chung.

Contributor Information

Yae Won Park, Email: yaewonpark@yuhs.ac.

Seok Jong Chung, Email: sjchung@yuhs.ac.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41531-023-00566-1.

References

- 1.Hely MA, et al. The Sydney multicenter study of Parkinson’s disease: the inevitability of dementia at 20 years. Mov. Disord. 2008;23:837–844. doi: 10.1002/mds.21956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams-Gray CH, et al. Evolution of cognitive dysfunction in an incident Parkinson’s disease cohort. Brain. 2007;130:1787–1798. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stoessl AJ, Martin WRW, McKeown MJ, Sossi V. Advances in imaging in Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10:987–1001. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70214-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McKinlay A, Grace RC, Dalrymple-Alford JC, Roger D. Characteristics of executive function impairment in Parkinson’s disease patients without dementia. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2010;16:268–277. doi: 10.1017/S1355617709991299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chung SJ, et al. Effect of striatal dopamine depletion on cognition in de novo Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2018;51:43–48. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2018.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chung SJ, et al. Patterns of striatal dopamine depletion in early Parkinson disease: prognostic relevance. Neurology. 2020;95:e280–e290. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shin NY, et al. Adverse effects of hypertension, supine hypertension, and perivascular space on cognition and motor function in PD. NPJ Parkinson’s Dis. 2021;7:69. doi: 10.1038/s41531-021-00214-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park YW, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging-visible perivascular spaces in basal ganglia predict cognitive decline in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2019;34:1672–1679. doi: 10.1002/mds.27798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baggio HC, Junqué C. Functional MRI in Parkinson’s disease cognitive impairment. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2019;144:29–58. doi: 10.1016/bs.irn.2018.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gillies RJ, Kinahan PE, Hricak H. Radiomics: images are more than pictures, they are data. Radiology. 2016;278:563–577. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015151169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Molina D, et al. Influence of gray level and space discretization on brain tumor heterogeneity measures obtained from magnetic resonance images. Comput Biol. Med. 2016;78:49–57. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2016.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Phongpreecha T, et al. Multivariate prediction of dementia in Parkinson’s disease. NPJ Parkinson’s Dis. 2020;6:20. doi: 10.1038/s41531-020-00121-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guo Y, et al. Predictors of cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. J. Neurol. 2021;268:2713–2722. doi: 10.1007/s00415-020-09757-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chung SJ, et al. Factor analysis-derived cognitive profile predicting early dementia conversion in PD. Neurology. 2020;95:e1650–e1659. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000010347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chan, D. K. Y. et al. Plasma biomarkers inclusive of α-synuclein/amyloid-beta40 ratio strongly correlate with Mini-Mental State Examination score in Parkinson’s disease and predict cognitive impairment. J. Neurol.269, 6377–6385 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Shen J, et al. Plasma MIA, CRP, and albumin predict cognitive decline in Parkinson’s disease. Ann. Neurol. 2022;92:255–269. doi: 10.1002/ana.26410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chung SJ, et al. Clinical relevance of amnestic versus non-amnestic mild cognitive impairment subtyping in Parkinson’s disease. Eur. J. Neurol. 2019;26:766–773. doi: 10.1111/ene.13886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chung SJ, et al. Frontal atrophy as a marker for dementia conversion in Parkinson’s disease with mild cognitive impairment. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2019;40:3784–3794. doi: 10.1002/hbm.24631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chung SJ, et al. Mild cognitive impairment reverters have a favorable cognitive prognosis and cortical integrity in Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 2019;78:168–177. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2019.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chung SJ, et al. Association between white matter connectivity and early dementia in patients with Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2022;98:e1846–e1856. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000200152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cao X, et al. A radiomics approach to predicting Parkinson’s disease by incorporating whole-brain functional activity and gray matter structure. Front Neurosci. 2020;14:751. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2020.00751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu P, et al. Parkinson’s disease diagnosis using neostriatum radiomic features based on T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. Front. Neurol. 2020;11:248. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.00248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Betrouni N, et al. Texture-based markers from structural imaging correlate with motor handicap in Parkinson’s disease. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:2724. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-81209-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salmanpour MR, et al. Robust identification of Parkinson’s disease subtypes using radiomics and hybrid machine learning. Comput Biol. Med. 2021;129:104142. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2020.104142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shu ZY, et al. Predicting the progression of Parkinson’s disease using conventional MRI and machine learning: an application of radiomic biomarkers in whole-brain white matter. Magn. Reson. Med. 2021;85:1611–1624. doi: 10.1002/mrm.28522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kang, J. J. et al. Combining quantitative susceptibility mapping to radiomics in diagnosing Parkinson’s disease and assessing cognitive impairment. Eur. Radiol.32, 6992–7003 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Tang C, et al. An individualized prediction of time to cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease: a combined multi-predictor study. Neurosci. Lett. 2021;762:136149. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2021.136149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tustison N, Gee J. Run-length matrices for texture analysis. Insight J. 2008;1:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wallis LI, et al. MRI assessment of basal ganglia iron deposition in Parkinson’s disease. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2008;28:1061–1067. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Daida K, et al. The presence of cerebral microbleeds is associated with cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. Sci. 2018;393:39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2018.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang J, et al. MRI evaluation of asymmetry of nigrostriatal damage in the early stage of early-onset Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2015;21:590–596. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2015.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perier C, Agid Y, Hirsch EC, Feger J. Ipsilateral and contralateral subthalamic activity after unilateral dopaminergic lesion. Neuroreport. 2000;11:3275–3278. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200009280-00045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Williams-Gray CH, et al. The distinct cognitive syndromes of Parkinson’s disease: 5 year follow-up of the CamPaIGN cohort. Brain. 2009;132:2958–2969. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Achard S, et al. A resilient, low-frequency, small-world human brain functional network with highly connected association cortical hubs. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:63–72. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3874-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Booth, S., Park, K. W., Lee, C. S. & Ko, J. H. Predicting cognitive decline in Parkinson’s disease using FDG-PET-based supervised learning. J. Clin. Investig.132, (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Shin N-Y, et al. Cortical thickness from MRI to predict conversion from mild cognitive impairment to dementia in Parkinson disease: a machine learning-based model. Radiology. 2021;300:390–399. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2021203383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spooner A, et al. A comparison of machine learning methods for survival analysis of high-dimensional clinical data for dementia prediction. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:20410. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-77220-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hanley JA, McNeil BJ. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology. 1982;143:29–36. doi: 10.1148/radiology.143.1.7063747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB, Sr., D’Agostino RB, Jr., Vasan RS. Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: from area under the ROC curve to reclassification and beyond. Stat. Med. 2008;27:157–172. doi: 10.1002/sim.2929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kerr KF, et al. Net reclassification indices for evaluating risk prediction instruments: a critical review. Epidemiology. 2014;25:114–121. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McKearnan SB, et al. Performance of the net reclassification improvement for nonnested models and a novel percentile-based alternative. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2018;187:1327–1335. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwx374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hughes AJ, Daniel SE, Kilford L, Lees AJ. Accuracy of clinical diagnosis of idiopathic Parkinson’s disease: a clinico-pathological study of 100 cases. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1992;55:181–184. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.55.3.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kang, Y. W., Jang, S. M. & Na, D. L. Seoul Neuropsychological Screening Battery (SNSB-II), 2nd edn. (Human Brain Research & Consulting Co., 2012).

- 44.Dubois B, et al. Diagnostic procedures for Parkinson’s disease dementia: recommendations from the movement disorder society task force. Mov. Disord. 2007;22:2314–2324. doi: 10.1002/mds.21844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chin J, et al. Re-standardization of the Korean-Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (K-IADL): clinical usefulness for various neurodegenerative diseases. Dement Neurocogn. Disord. 2018;17:11–22. doi: 10.12779/dnd.2018.17.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yoo HS, et al. The influence of body mass index at diagnosis on cognitive decline in Parkinson’s disease. J. Clin. Neurol. 2019;15:517–526. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2019.15.4.517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Halliday G, Hely M, Reid W, Morris J. The progression of pathology in longitudinally followed patients with Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neuropathologica. 2008;115:409–415. doi: 10.1007/s00401-008-0344-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Næss-Schmidt E, et al. Automatic thalamus and hippocampus segmentation from MP2RAGE: comparison of publicly available methods and implications for DTI quantification. Int. J. Comput. Assist Radiol. Surg. 2016;11:1979–1991. doi: 10.1007/s11548-016-1433-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Romero JE, Coupé P, Manjón JV. HIPS: a new hippocampus subfield segmentation method. Neuroimage. 2017;163:286–295. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.09.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tustison NJ, et al. N4ITK: improved N3 bias correction. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 2010;29:1310–1320. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2010.2046908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.van Griethuysen JJM, et al. Computational radiomics system to decode the radiographic phenotype. Cancer Res. 2017;77:e104–e107. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zwanenburg A, et al. The image biomarker standardization initiative: standardized quantitative radiomics for high-throughput image-based phenotyping. Radiology. 2020;295:328–338. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020191145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pedregosa F, et al. Scikit-learn: machine learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011;12:2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nti IK, Nyarko-Boateng O, Aning J. Performance of machine learning algorithms with different K values in K-fold cross-validation. Int. J. Inf. Technol. Comput. Sci. 2021;13:61–71. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hilden J, Habbema JD, Bjerregaard B. The measurement of performance in probabilistic diagnosis. II. Trustworthiness of the exact values of the diagnostic probabilities. Methods Inf. Med. 1978;17:227–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Park SY, Park JE, Kim H, Park SH. Review of statistical methods for evaluating the performance of survival or other time-to-event prediction models (from conventional to deep learning approaches) Korean J. Radiol. 2021;22:1697–1707. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2021.0223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Steyerberg EW, et al. Assessing the performance of prediction models: a framework for traditional and novel measures. Epidemiology. 2010;21:128–138. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181c30fb2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Steyerberg EW, et al. Assessing the performance of prediction models: a framework for some traditional and novel measures. Epidemiology. 2010;21:128. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181c30fb2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics. 1988;44:837–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB, Sr., Steyerberg EW. Extensions of net reclassification improvement calculations to measure usefulness of new biomarkers. Stat. Med. 2011;30:11–21. doi: 10.1002/sim.4085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lundberg, S. M. & Lee, S.-I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. Adv. Neural. Inf. Process. Syst.30 (2017).

- 62.Molnar, C. Interpretable machine learning (Lulu. com, 2020).

- 63.Awe, A. M. et al. Machine learning principles applied to CT radiomics to predict mucinous pancreatic cysts. Abdominal Radiol.10.1007/s00261-021-03289-0 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 64.Giraud, P. et al. Interpretable machine learning model for locoregional relapse prediction in oropharyngeal cancers. Cancers13, 57 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data and codes used for this study is available from the corresponding author on request.