Abstract

Fragile X syndrome is caused by the expansion of CGG triplets in the FMR1 gene, which generates epigenetic changes that silence its expression. The absence of the protein coded by this gene, FMRP, causes cellular dysfunction, leading to impaired brain development and functional abnormalities. The physical and neurologic manifestations of the disease appear early in life and may suggest the diagnosis. However, it must be confirmed by molecular tests. It affects multiple areas of daily living and greatly burdens the affected individuals and their families. Fragile X syndrome is the most common monogenic cause of intellectual disability and autism spectrum disorder; the diagnosis should be suspected in every patient with neurodevelopmental delay. Early interventions could improve the functional prognosis of patients with Fragile X syndrome, significantly impacting their quality of life and daily functioning. Therefore, healthcare for children with Fragile X syndrome should include a multidisciplinary approach.

Keywords: Fragile X Syndrome, fragile x mental retardation protein, child, pediatrics, developmental disabilities

Resumen

El síndrome de X frágil es causado por la expansión de tripletas CGG en el gen FMR1, el cual genera cambios epigenéticos que silencian su expresión. La ausencia de la proteína codificada por este gen, la FMRP, causa disfunción celular, llevando a deficiencia en el desarrollo cerebral y anormalidades funcionales. Las manifestaciones físicas y neurológicas de la enfermedad aparecen en edades tempranas y pueden sugerir el diagnóstico. Sin embargo, este debe ser confirmado por pruebas moleculares. El síndrome afecta múltiples aspectos de la vida diaria y representa una alta carga para los individuos afectados y para sus familias. El síndrome de C frágil es la causa monogénica más común de discapacidad intelectual y trastornos del espectro autista; por ende, el diagnóstico debe sospecharse en todo paciente con retraso del neurodesarrollo. Intervenciones tempranas podrían mejorar el pronóstico funcional de pacientes con síndrome de X frágil, impactando significativamente su calidad de vida y funcionamiento. Por lo tanto, la atención en salud de niños con síndrome de X frágil debe incluir un abordaje multidisciplinario.

Palabras clave: Síndrome del cromosoma X frágil, proteína del retraso mental del síndrome del cromosoma X frágil, niño, pediatría, discapacidades del desarrollo

Remark

| 1) Why was this study conducted? |

| Because Fragile X Syndrome is a prevalent disease, with the world's most significant genetic cluster in Colombia. Research studies have led to recent advances and changes in paradigms of Fragile X syndrome, which have not been critically presented yet to the scientific public targeted by this journal. |

| 2) What were the most relevant results of the study? |

| We conducted an updated and focused literature review that includes current perspectives in molecular and clinical aspects of Fragile X syndrome. It presents valuable contents for scientists, general practitioners, pediatricians and medical students. |

| 3) What do these results contribute? |

| To understand the basic and clinical aspects of Fragile X syndrome will contribute to the early suspicion, diagnosis, and treatment of the affected individuals. There is growing evidence that prompt interventions in children Fragile X syndrome will improve their outcomes, which positively impact their and their caregivers' life’s. |

Introduction

Fragile X Syndrome, OMIM # 300624, is a genetic disease caused by the absence of Fragile X Messenger RibonucleoProtein (FMRP), which has multiple important functions in the nervous system and in the connective tissue 1 . Those affected with Fragile X syndrome present neurodevelopmental abnormalities such as intellectual disability, autism spectrum disorder, deficits in language, anxiety, hypersensitivity, and attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder 2 . Likewise, connective tissue involvement manifests as large and protruding ears, macroorchidism, hyperextensible finger joints, flat feet, mitral valve prolapse and occasional hernias 3 , 4 .

The absence of FMRP is caused by the silencing of the gene FMR1 (FMR1: Fragile X Messenger Ribonucleoprotein1), with locus Xq27.3. In most cases, the absence of FMRP is explained by methylation of the 5' untranslated region (5'UTR) of FMR1, which occurs when there are over 200 CGG repeats, called the full mutation. Individuals with an allele with CGG repeats between 55 and 200 are called premutation carriers; FMRP expression is typically normal but sometimes is lower when the premutation is >120 repeats. Alleles with 45 to 54 repeats correspond to the gray zone and alleles with 44 or fewer repeats are considered normal; in both cases, FMRP production is normal 5 . Generally, women with a full mutation are less severely affected than men due to their second FMR1 allele can partially compensate for the FMRP deficit 6 .

Premutation carriers may present with FMR1-associated disorders. They can present with late-onset conditions such as fragile X-associated tremor ataxia syndrome and females can present with fragile X-associated primary ovarian insufficiency 7 . Carriers have a higher prevalence of depression, anxiety, and attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder in childhood and adulthood, called fragile X-associated neuropsychiatric disorders 2 .

The main goal of this narrative revision is to improve understanding of Fragile X syndrome and raise awareness among health professionals about identifying signs and symptoms of the syndrome in the pediatric population. This will lead to early diagnosis and specific treatments to improve the quality of life of patients and their families.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of Fragile X syndrome has varied depending on the diagnostic tests used and in the population being evaluated in the studies. Fragile X syndrome diagnosis has evolved from cytogenetic testing in the 70s to Southern Blot and Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) with primers in the 90s, to triple primer PCR (TP-PCR) and capillary electrophoresis to quantify CGG triplets currently 8 .

The prevalence of full mutation in newborns varies depending on the region where the study is conducted. Coffee et al. 9 , in 2009, assessed 36,124 male newborns in Georgia, finding a prevalence of the full mutation of 1 in 5,161. Tassone et al. 10 , in 2012 evaluated 7,312 males and 6,895 females in California, finding one case of full mutation in males and none in females. In Spain, the studies by Fernandez-Carvajal et al. 11 , and Rifé et al. 12 , in two regions of the country reported very similar prevalence of the full mutation in male newborns: 1:2,633 and 1:2,466, respectively. More studies are needed to estimate the local frequency in latitudes still unknown.

Multiple genetic clusters have been described worldwide, including Indonesia 13 , Finland 14 , Cameroon 15 , and the island of Mallorca, in Spain 16 . However, in Ricaurte, a town located in Colombia, a geographic conglomerate with the highest prevalence in the world of alleles with triplet expansion has been described 17 . The prevalence of full mutation is 1:21 (482 per 10,000) in males and 1:48 (205 per 10,000) in females, which is 343 and 226 times higher than the global estimate, respectively. Regarding the frequency of the premutation, it was 1:71 in males and 1:28 in females. This genetic cluster is probably the consequence of a strong founder effect.

The prevalence of the full mutation in individuals with an intellectual disability is approximately 2.4% 18 . However, the prevalence of Fragile X syndrome in girls with intellectual disabilities is lower than in boys 19 - 22 . Fragile X syndrome is recognized as one of the main monogenetic causes of autism spectrum disorder, with a prevalence varying between 2% and 12% in individuals with autism spectrum disorder 2 , 23 , 24 . As with intellectual disability, the low prevalence of the full mutation in females with autism spectrum disorder is likely due to underdiagnosis, rather than to the actual distribution of these alleles.

In 2014, Hunter et al. 18 , conducted a meta-analysis that included 54 epidemiological studies evaluating the prevalence of expanded FMR1 alleles in different populations. On the one hand, they estimated that the full mutation was present in 1.4 per 10,000 (1:7,143) males and 0.9 per 10,000 (1:11,111) females. On the other hand, the alleles with premutation were estimated at 11.7 per 10,000 (1:855) males and 34.4 per 10,000 (1:291) females. However, the heterogeneity was high, and the estimates have wide confidence intervals.

The FMR1 gene

The silencing of the FMR1 gene explains the phenotype through the lack of FMRP in Fragile X syndrome. The FMR1 gene, with locus Xq27.3, is composed of 17 exons and has a length of 38 kb. FMR1 normally has a mean of 30 CGG trinucleotide repeats in the 5'UTR 8 , 25 . These CGG repeats can expand in germ cell meiosis from one allele in the gray zone to one in the premutation range and, more frequently, from premutation to an allele in the full mutation when passed on by a female carrier.

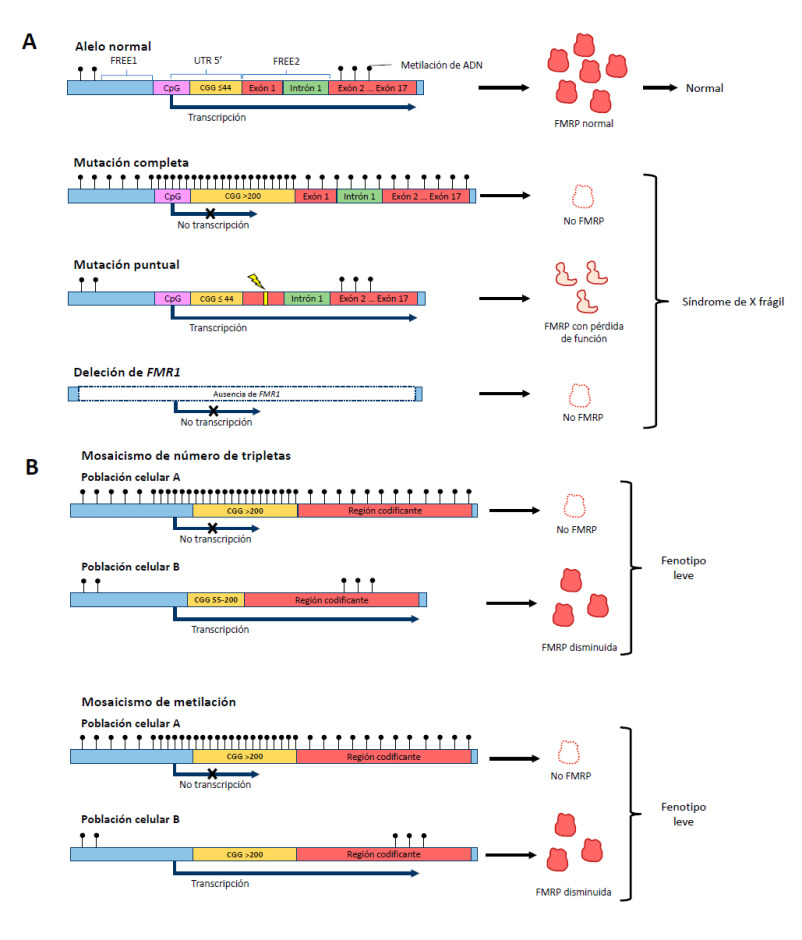

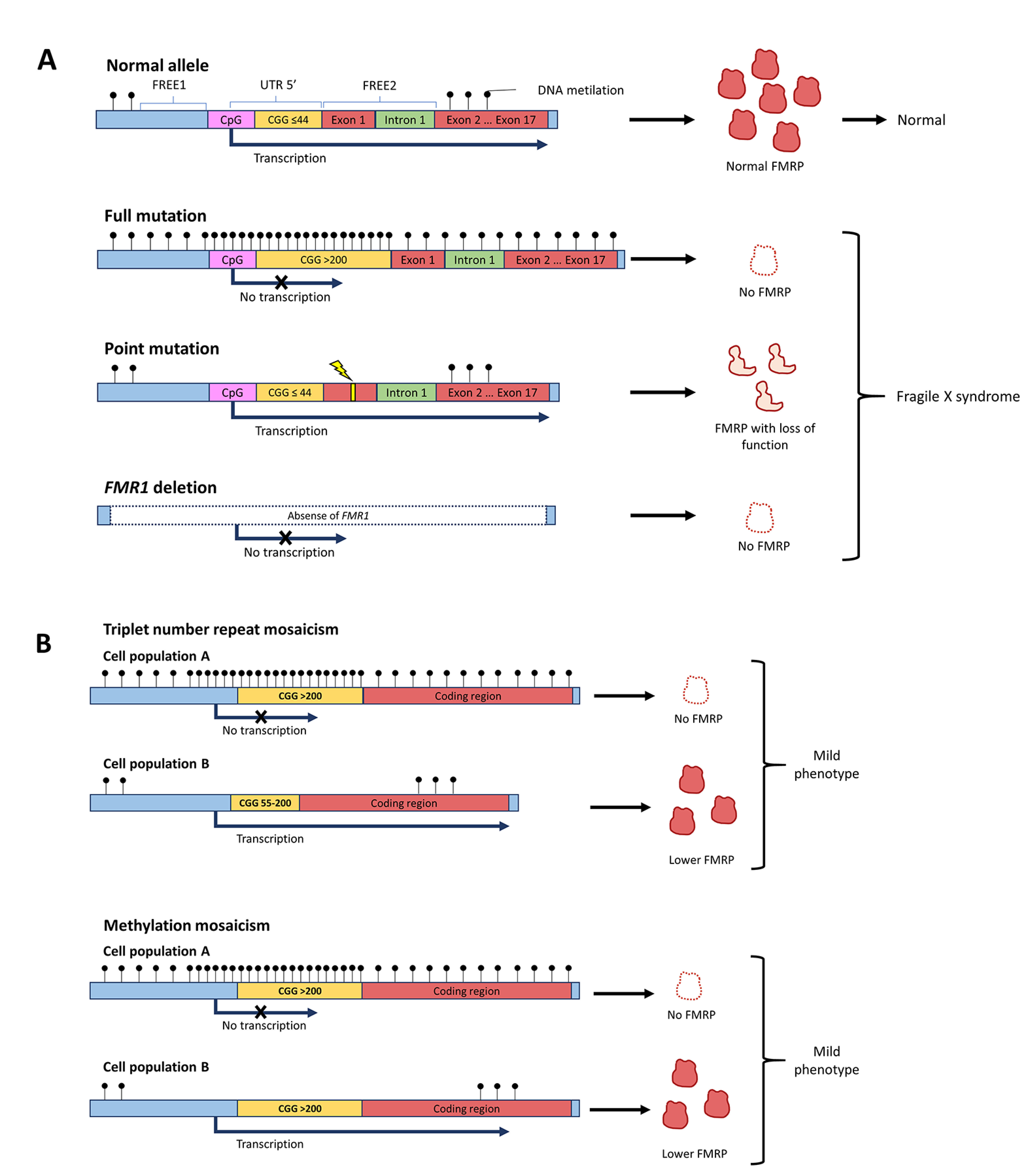

Different alterations in the FMR1 gene explain the non-production of FMRP and the phenotype of Fragile X syndrome (Figure 1A). Most cases of Fragile X syndrome are caused by the expansion of over 200 CGG repeats in the 5 'UTR region of FMR1. However, about 1% of Fragile X syndrome cases are secondary to deletions that include the FMR1 locus or pathogenic point mutations in the gene's coding region 26 , 27 . These genetic alterations generate the absence or loss of function of FMRP 28 . Until 2020, 22 cases of point mutations had been reported in the literature 28 , 29 . Fragile X syndrome meets the criteria for genetic heterogeneity.

Figure 1. Genetic aspects of Fragile X syndrome. A. Different alleles can give rise to Fragile X syndrome. Even though the most common is the triplet-expansion allele, point mutations in FMR1 or deletion of the gene can produce a phenotype of Fragile X syndrome. B. The severity of the phenotype can be reduced if there are mosaicisms. Mosaicism can be in the number of CGG triplets or in the methylation status of the gene.

The FMR1 gene is silenced by epigenetic modifications that induce structural changes in the conformation of the heterochromatin, which prevents gene transcription. In FMR1 alleles with more than 200 CGG repeats in the 5 'UTR region, an excess of methylation occurs in the region with triplet expansion and in the CpG islands of the promoter region, preventing the transcription machinery from interacting and coupling with the promoter 30 . Likewise, in full mutation a sequence located between 650 to 800 nucleotides upstream of the CGG repeats promotes the methylation of regions called fragile X-related epigenetic element 1 (FREE1) and 2 (FREE2), located in the promoter and intron 1 of the FMR1, respectively 31 . On the other hand, histone deacethylation and methylation occur, altering the quaternary conformation of FMR1 and preventing the access of transcription factors 5 , 32 . The sum of these events results in no transcription of the messenger RNA (mRNA) that codes for FMRP; consequently, there is little or no FMRP produced.

Mosaicism in the FMR1 expression has been found in individuals with Fragile X syndrome, which may result from differences in the number of CGG repetitions or in the methylation status of the gene (Figure 1B). In the triplet repeats mosaicism, some cells have the full mutation allele, while others present the premutation range allele 30 . In contrast, in the methylation mosaicism some individuals with the full mutation silence the FMR1 gene in some cells and not in others 30 . In those affected by Fragile X syndrome with mosaicism, different amounts of FMRP are produced between cell populations and these individuals have a less severe phenotype 33 .

Females with the FMR1 full mutation have a less severe phenotype when the active X chromosome has the normal FMR1 allele. Somatic cells with two X chromosomes regularly inactivate one of them through total methylation, producing an activation ratio of 50%. However, in women with a full mutation allele, an activation ratio of around 60% means that 60% of the cells has the normal X as the active X and these cells are producing FMRP, making the phenotype less severe than what is seen in the males. The higher the activation ratio the better the intelligence quotient in females 34 . The selective inactivation of the mutated X chromosome is most prominent during infancy and puberty and may improve with age at least in studies in blood, producing variable expression of the phenotype in females with the full mutation 34 . In permutation, the production of FMR1 mRNA increases up to 8-fold the normal level, but the production of FMRP is lower than in healthy individuals 7 . The FMR1 mRNA aggregates, forming inclusions that are thought to have a toxic effect, which leads to neuronal dysfunction and the clinical manifestations seen in permutation 7 . These syndromes, however, are observed during adulthood in permutation carriers and not in children with full mutation.

Genetic counseling

When an index case of Fragile X syndrome is diagnosed, a cascade approach to the family is indicated to identify carriers of the premutation or other cases of full mutation. A pedigree study should be performed as an initial measure, followed by diagnostic tests on the family members at risk for an expanded allele. With the results, one should establish the risk of progeny with normal, premutation, or full mutation alleles.

The inheritance of Fragile X syndrome is through the X chromosome but is atypical given that the mutation is dynamic due to the anomalous expansion in the CGG triplet number from one generation to the other. Men who are premutation carriers inherit the X chromosome to all their daughters with the same number of repeats and do not inherit the X chromosome to their sons. On the other hand, women with the premutation can inherit the X chromosome carrying the premutation to male and female children with the same number of triplets or with the number of triplets expanded to the full mutation range; therefore, having children affected by Fragile X syndrome. Men with full mutation inherit the full mutation to every daughter but not their sons. In contrast, women with full mutation inherit the full mutation allele to 50% of both sons and daughters. Therefore, every time a man has Fragile X syndrome, his mother will be carriers of the premutation or will have a full mutation.

The probability of triplet expansion from female premutation carriers to their progeny depends on various factors. First, the higher the number of CCG repeats, the higher the probability of expansion; that is, the probability of triplet expansion from 58 triplets to full mutation is 2.7%, while the probability when the triplet number is 100 or higher is 100%. Second, the higher the age of conception, the higher the probability of expansion. Lastly, the higher the number of AGG interruptions within the CGG triplets, the lower the probability of expansion. The genetic counseling of women with premutation must be individualized.

FMRP

FMRP is an RNA-binding protein expressed in the brain and testes at high levels. It is detectable from embryonic development in neural progenitor cells and throughout extrauterine life in neurons and mature glial cells 35 . Its structure includes interaction domains with RNA, chromatin, and proteins 36 . It also has a sequence of amino acids that allows it to be transported bidirectionally between the nucleus and the cytoplasm 36 . In the cytoplasm, FMRP is located with polyribosomes, binds to target mRNAs, and suppresses their translation by preventing ribosomal translocation on mRNA 37 . In addition, FMRP modulates the translation of mRNAs through miRNAs by interacting with the RNA Induced Silencing Complex (RISC) 37 . Furthermore, it has been reported that it indirectly modifies gene expression by transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms by regulating the translation of transcription factors and chromatin-modifying proteins 38 . FMRP is a protein that has a neural function by modulating the expression of other proteins at various levels.

In the absence of FMRP, neuronal morphogenesis is altered 39 , 40 . In the brains of those affected by Fragile X syndrome, a higher density of synaptic spines has been observed in the dendrites, which adopt an elongated, thin, and tortuous immature structure 41 . Spine dysmorphogenesis and instability generate functional defects in synaptic plasticity, associated with learning and memory processes defects 5 , 41 . One of the proteins involved in the aberrant morphology of dendritic spines is Matrix Metalloproteinase 9 (MMP 9), an extracellular enzyme involved in synaptic remodeling. With lowered FMRP levels, MMP9 is produced in excess 42 .

The lack of FMRP generates an exaggerated and dysregulated translation of mRNAs in the presynaptic and postsynaptic terminals, which alters the neuronal excitation-inhibition balance. There is an increase in the number and activity of metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluR) 1 and 5 and ionotropic N-methyl-D-aspartic acid (NMDA-R) type receptors, and internalization of α-amino-3- -hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionic type receptors (AMPA-R), which generate defects in the integration of neuronal circuits and changes in the synaptic architecture that alter neuronal plasticity 41 , 43 . On the other hand, the reduced levels of FMRP induce a decrease in the expression of GABA receptors, which would generate a state of less inhibition in neuronal communication 37 , 41 . The result of the imbalance in the neuronal signaling systems is a state of hyperexcitability, which explains disorders such as hypersensitivity to sensory stimuli, anxiety, autism spectrum disorder behavior, hyperactivity, sleep disorders, and epileptic seizures, among other symptoms of those affected by Fragile X syndrome 2 , 41 , 44 .

FMRP regulates the expression of synaptic proteins that meet on altered signaling pathways in individuals with intellectual disability and an autism spectrum disorder. Without FMRP, cellular signaling pathways such as Wnt, PI3K / AKT / mTOR, and ERK / MAPK are altered, which are implicated in neurodevelopmental processes and neuronal plasticity for many disorders 45 . Similarly, mutations in genes regulated by FMRP have been reported to be associated with neuropsychiatric disorders. The lack of FMRP explains why those affected by Fragile X syndrome have many behavioral and cognitive features similar to other neurodevelopmental disorders, including autism spectrum disorder 2 , 46 .

Due to the loss of FMRP in Fragile X syndrome, the endocannabinoid pathway is altered in the central nervous system (CNS). In murine models without FMRP, a decrease is observed in the levels of endogenous cannabinoids such as anandamide and 2-arachidonylglycerol, decreasing the stimulation of neuronal CB1 endocannabinoid receptors 47 . This phenomenon is related to social disability, deficits in memory, learning, and anxiety 47 , 48 . Phytocannabinoids such as cannabidiol (CBD) have been used recently as a therapy in Fragile X syndrome 45 , 47 .

FMRP is expressed in almost all human tissue, but with a repertoire of target genes differentiated according to the proteome of the cell population 37 . FMRP regulates the expression of modifying extracellular matrix proteins, such as MMP 9, actin, and elastin, which is associated with findings in connective tissue in patients with Fragile X syndrome 3 . Additionally, FMRP levels have been reported to be especially high in gonads; it has been proposed that in the absence of FMRP in the testis, there is a connective tissue dysplasia and overproduction of proteins leading to macroorchidism 4 . The broad expression of FMRP explains the pleiotropism and variability of the Fragile X syndrome phenotype.

The phenotype in children with Fragile X Syndrome

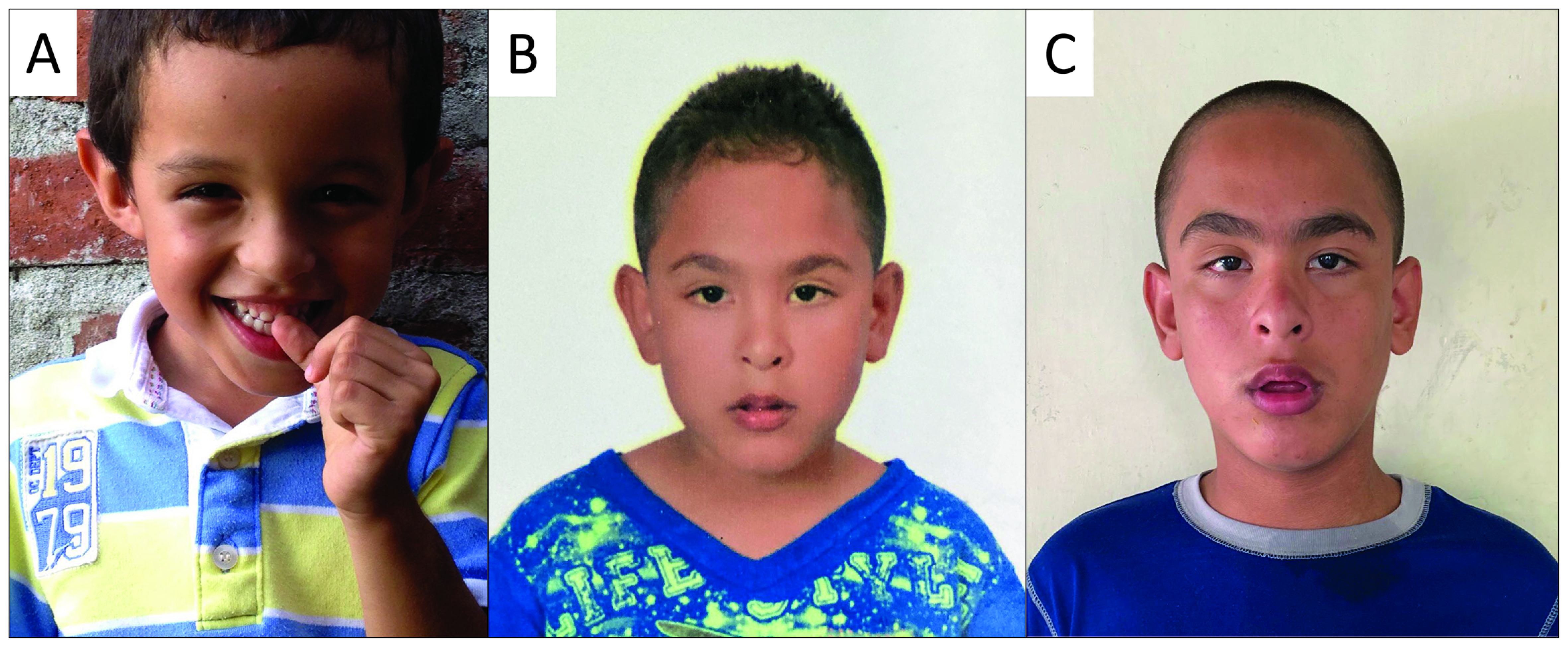

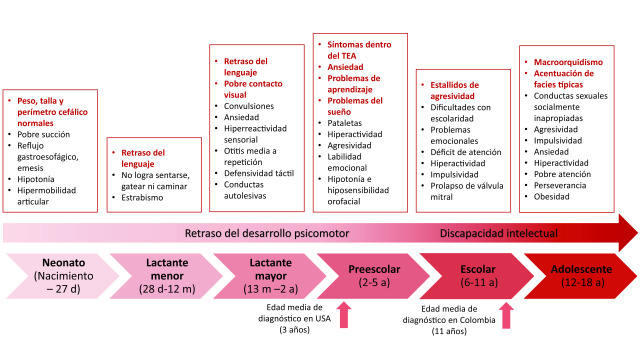

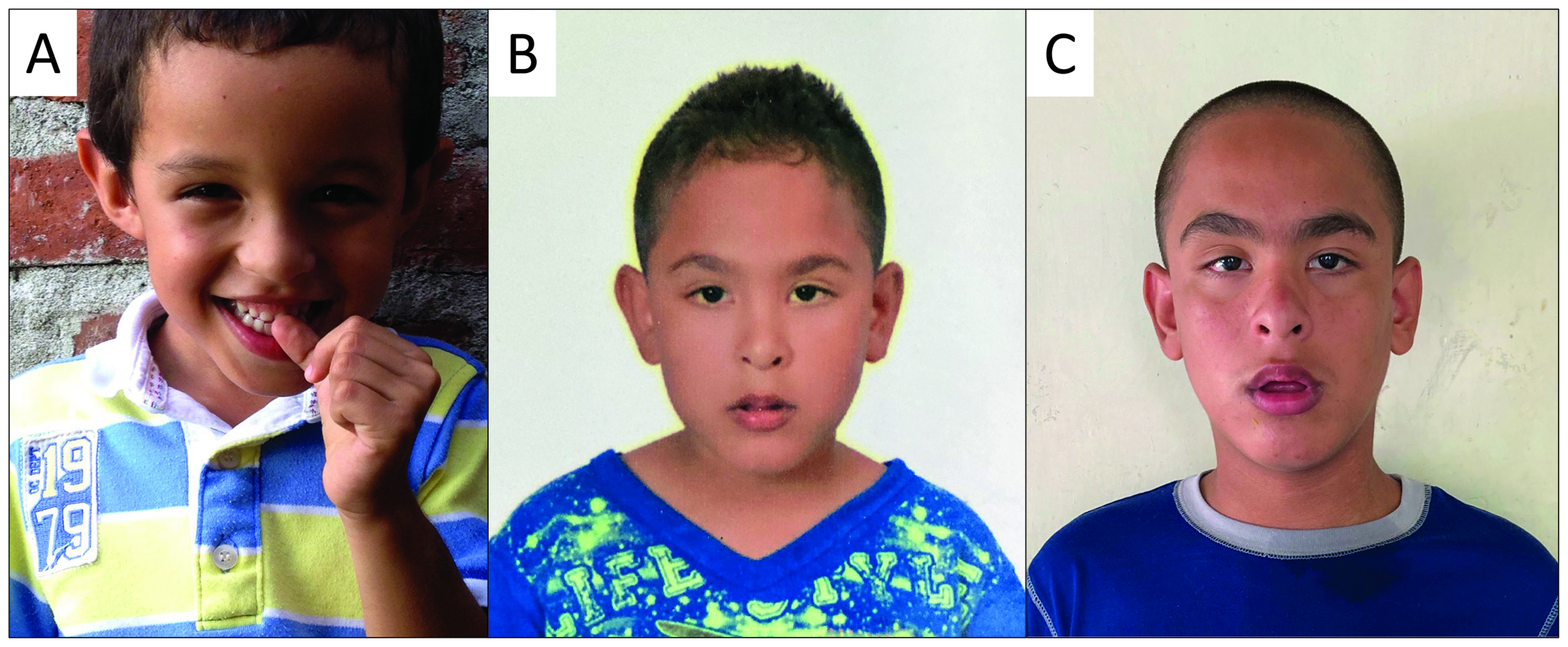

In children with Fragile X syndrome, the phenotype is variable and depends on many factors (Figure 2). In the first place, the severity is inversely proportional to levels of FMRP, which may differ among individuals with full mutation depending on the presence of repeat size or methylation mosaicism. In the second place, in women, the phenotype is less severe than in men and has a broader range of manifestations depending on the activation ratio. Finally, the phenotype may be aggravated if other genes associated with Fragile X syndrome manifestations are altered. For example, a case of Fragile X syndrome with intellectual disability and severe autism spectrum disorder was reported with a deletion that included the gene PTCHD1-AS 29 . In children with the full mutation of FMR1, the phenotypic expression is influenced by multiple molecular variables and background genetic defects, either pathological or with a normal variation that can be additive to the phenotype.

Figure 2. The phenotype of children with Fragile X syndrome is variable between individuals and during the stages of development. Some children may have a typical phenotype since early age (A), while others can have subtler or even absent physical manifestations (6 y.o.) (B). However, the physical characteristics of Fragile X syndrome may accentuate during the adolescence, as illustrated by the same patient from panel B, nowadays at with 13 y.o. (C). The diagnosis is not based solely on physical characteristics, as they are not sufficiently sensitive and specific. *The patients and their guardians authorized the use of their image by informed consent.

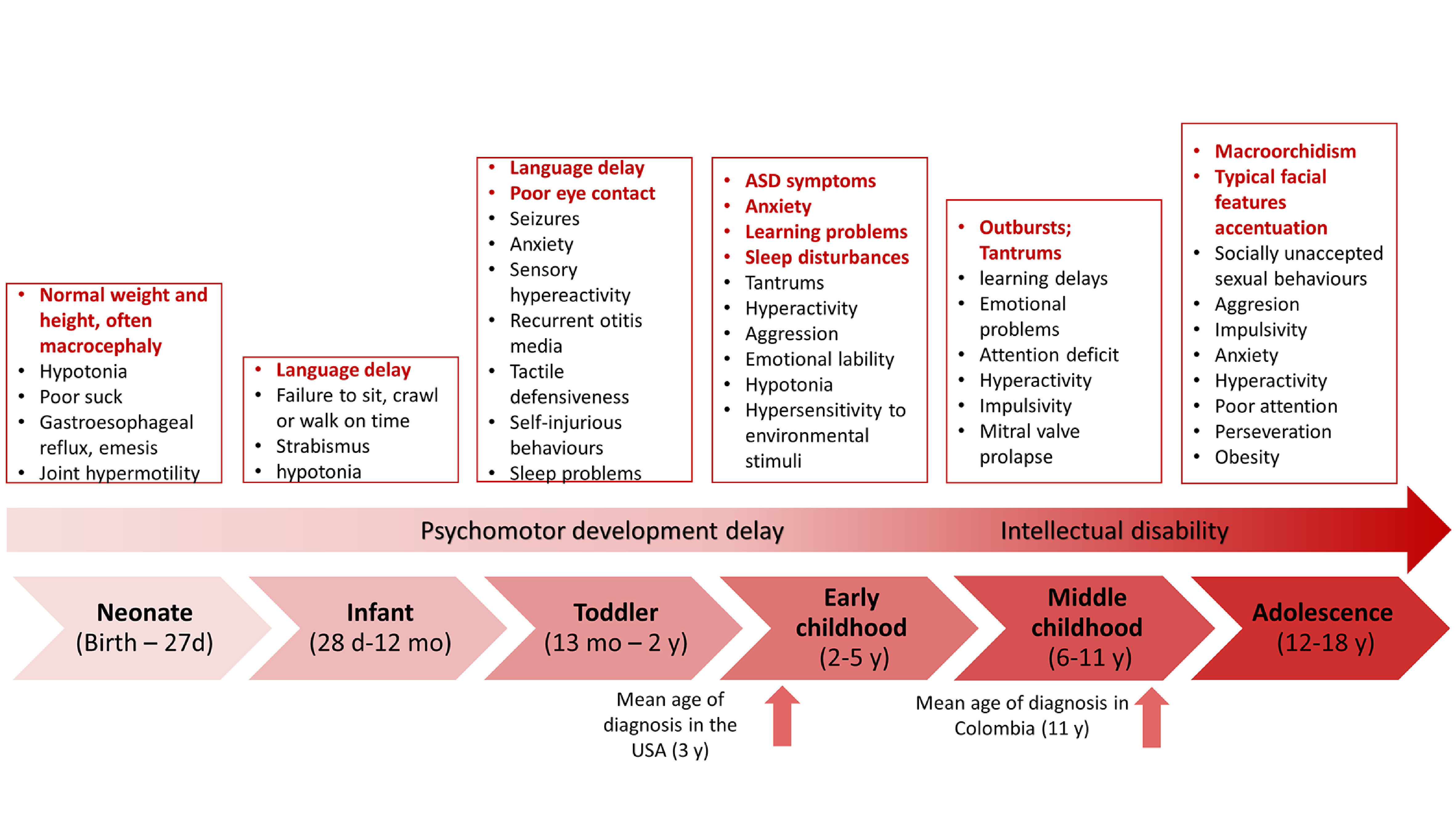

The phenotype in children with Fragile X syndrome also varies depending on age and is closer to the classic physical phenotype by the end of adolescence (Figure 3). In prenatal and neonatal diagnosis, there are no ultrasonographic nor physical findings specific to Fragile X syndrome except for the DNA studies that should be done on anyone with an intellectual disability or autism spectrum disorder 49 . One of the first signs in children that suggest the diagnosis is failure to reach developmental milestones such as language by 2 y.o. and walking by 1 y.o 50 . In addition, in preschool children, symptoms within the autism spectrum disorder phenotype, such as impairment of social communication, social anxiety, absence of eye contact, and stereotypic behavior, including hand flapping and hand biting, are often observed. Parents, caregivers, or teachers may detect irritable behavior, hyperarousal and learning problems 51 . In early to middle childhood and adolescence, neuropsychiatric disorders such as attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder and anxiety appear, and physical characteristics typical of Fragile X syndrome become more evident as they age 49 . In Table 1, the phenotype of children and adults is compared and outlined.

Figure 3. The phenotype of Fragile X syndrome varies with age. Some manifestations are present early in life, while others appear when the patient reaches adulthood. Some manifestations, such as seizures and otitis media, tend to disappear with age.

Table 1. Phenotypic characteristics of children and adults with Fragile X syndrome.

| Characteristic | Children | Adults |

|---|---|---|

| Neurodevelopmental/psychiatric | ||

| Intellectual disability (~100% in boys) | +++ | +++ |

| Psychomotor delay (~100% in boys) | +++ | NA |

| Verbal language delay (~100% in boys) | +++ | ++ |

| Attention deficit (74-84%) | +++ | ++ |

| Hyperactivity (50-66%) | +++ | ++ |

| Anxiety disorder (58-86%) | +++ | ++ |

| Autism spectrum disorder (50-60%) | +++ | +++ |

| Sleep disorder (30%) | ++ | + |

| Depression (8-12%) | ++ | +++ |

| Aggressive behavior (20-30%) | +++ | ++ |

| Neurologic | ||

| Seizures (10-20%) | ++ | + |

| Abnormal electroencephalogram (30-74%) | +++ | + |

| Hypotonia | +++ | + |

| Craniofacial | ||

| Long face (83%) | + | +++ |

| Macrocephaly (81%) | + | +++ |

| Prominent ears (72-78%) | ++ | +++ |

| Broad forehead | ++ | +++ |

| Mandibular prognathism (80%) | - | +++ |

| Otopharyngeal | ||

| High palate (94%) | ++ | ++ |

| Dental malocclusion | ++ | +++ |

| Recurrent otitis media in first 5 years | + | - |

| Poor hearing (secondary to otitis) | + | - |

| Connective tissue problems | ||

| Joint hypermobility (metacarpophalangeal) | +++ | + |

| Pes planus | ++ | ++ |

| Pectus excavatum | + | + |

| Scoliosis | + | + |

| Congenital hip subluxation | rare | NA |

| Ophthalmological | ||

| Refraction defects (17-59%) | + | ++ |

| Strabismus (8-40%) | ++ | ++ |

| Nystagmus (5-13%) | + | + |

| Cardiovascular | ||

| Mitral valve prolapse (3-12%) | + | ++ |

| Aortic root dilation (25%) | + | ++ |

| Respiratory | ||

| Obstructive sleep apnea | + | ++ |

| Gastrointestinal | ||

| Feeding disorders | +++ | + |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease | +++ | +++ |

| Emesis | +++ | + |

| Genitourinary | ||

| Macroorchidism (90%) | +* | +++ |

| Inguinal hernia | +++ | +++ |

| Vesicoureteral reflux | + | + |

| Endocrinology | ||

| Precocious puberty | + | NA |

| Metabolic | ||

| Obesity | ++ | ++ |

The frequency of seizures varies according to age. Epilepsy appears between 2 and 10 years in approximately 16% of males and 5% of females 52 and may present as partial, generalized tonic-clonic, or absence seizures 49 . The prevalence of EEG abnormalities is much greater than clinically evident seizures, suggesting an intrinsically different electro-encephalic activity in children with Fragile X syndrome 53 . Both clinically evident seizures and epileptiform patterns in electroencephalogram tend to disappear in adulthood 54 .

The phenotype is less severe in girls with the full mutation than in boys 22 . In men with full mutation without mosaicism, Fragile X syndrome has complete penetrance and all present mild to-severe intellectual disability, while in women with full mutation, 30 % have intellectual disability, 30% have a borderline IQ, and 30% have an average IQ 55 . The symptoms of autism spectrum disorder are observed during early childhood in 60% of boys and 20% of girls with Fragile X syndrome 56 - 58 . Physical characteristics of girls with Fragile X syndrome are the same as the ones described in boys. However, they are less frequent and less severe. The phenotype in girls with Fragile X syndrome is harder to identify, although poor eye contact, anxiety, and hand flapping are usually present.

Diagnosis

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends genetic testing in children with delayed psychomotor development, autism spectrum disorder, borderline intellectual abilities, or evident intellectual disability 59 , 60 . Initially, Fragile X syndrome must be ruled out, even if the patient does not have physical characteristics suggestive of the syndrome using double-or triple-primer PCR plus capillary electrophoresis, which quantifies the number of triplets 49 . The diagnosis must be confirmed by Southern Blot, which provides the activation ratio of the X chromosome in women with Fragile X syndrome and detects copy number mosaicism in men and women. Simultaneously, other syndromes generated by copy number variants must be ruled out through comparative genomic hybridization. Finally, if the previous tests have not achieved the diagnosis, whole exome sequencing (WES), whole genome sequencing (WGS) or gene panels should be performed to identify molecular variants in genes associated with intellectual disability or autism spectrum disorder 59 , 60 . comparative genomic hybridization, WES and WGS do not assess the number of triplets in FMR1. Therefore, FMR1 DNA testing is essential in the work-up for those with autism spectrum disorder or intellectual disability.

The FMR1 DNA testing will not detect patients with Fragile X syndrome due to mutations in the coding region of FMR1 and therefore, WES or WGS is needed 29 . The number of patients with point mutations in FMR1 leading to a diagnosis of Fragile X syndrome when the CGG repeat number is in the normal range is increasing now that WES or WGS is carried out more frequently. However, these mutations are far less frequent than the full mutation leading to Fragile X syndrome. Therefore, the diagnosis of Fragile X syndrome must be confirmed through molecular tests like PCR with double or triple-primer and southern blot; when these tests are negative, but the clinical suspicion of Fragile X syndrome persists, WES and WGS are suggested.

Treatment

The treatment of Fragile X syndrome is symptomatic and targeted treatments to the molecular pathways altered in Fragile X syndrome. Up to date, no targeted treatment has proven sufficient effectiveness, nor have regulatory entities approved it for its specific use in Fragile X syndrome 61 . Therefore, we will focus on symptomatic management, considering the multiple clinical manifestations that patients may present. Regarding behavioral and psychiatric manifestations, it is important to highlight that patients with Fragile X syndrome are more sensitive to psychotropic medications than those with normal development. Thus, they should be initiated at low doses and gradually increased, given that they can present adverse effects with relatively low doses. Some medications cause paradoxical effects in some patients, with worsening of the symptoms attempted to improve; in those cases, discontinuation and change to drugs with different mechanisms of action is pertinent. There does not seem to be significant metabolic or pharmacokinetic alterations in the commonly used medications for Fragile X syndrome. Since the management of patients with fragile X syndrome varies throughout their developmental stages, the Table 2 presents recommended interventions at different ages.

Table 2. Interventions for children with Fragile X syndrome and their families across different ages.

| Prenatal | Neonate (Birth - 27d) | Infant (28d-12m) | Toddler (13m-2y) | Early childhood (2-5y) | Middle Childhood (6-11y) | Adolescent (12-18y) and young adult (18-21a) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genetics | |||||||

| Reproductive counseling for parents: Education, prognosis and risk of recurrence | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Molecular diagnosis in the pregnant woman | x | ||||||

| Routine prenatal care | x | ||||||

| Molecular diagnosis in the patient | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Neurodevelopment | |||||||

| Evaluate developmental milestones | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Auditory screening with brainsteam evoked potentials or otoacustic emissions | x | x | |||||

| Determine Intellectual Quotient and evaluate higher mental functions | x | x | x | x | |||

| Evaluate autism spectrum disorder behavior and sensorial integration, diagnostic tests | x | x | x | x | |||

| Neurologic | |||||||

| Ask about seizures (generalized, partial and absence). Electroencephalogram only if suspected | x | x | x | x | |||

| Evaluate the presence of motor tics | x | x | x | ||||

| Psychiatric | |||||||

| Inquire for depression and anxiety. Behavioral and pharmacologic treatment according to medical criteria | x | x | x | ||||

| Inquire for attention deficit and hyperactivity. Behavioral and pharmacologic treatment according to medical criteria | x | x | x | ||||

| Inquire for aggressiveness. Behavioral and pharmacologic treatment according to medical criteria | x | x | x | ||||

| Inquire for insomnia. Behavioral and pharmacologic (melatonin) treatment according to medical criteria | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Psychological services | |||||||

| Therapy for the family and caregiver | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Cognitive behavioral therapy | x | x | x | ||||

| Promote self-care abilities | x | x | |||||

| Sexual and reproductive education: control of problematic behaviors, consider desire for reproduction, educate on contraception and sexually transmitted diseases | x | ||||||

| Vocational education, develop independent living skills | x | ||||||

| Rehabilitation | |||||||

| Physical therapy: muscular strengthening, stability and proprioception | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Occupational therapy: develop activities of daily living skills, productivity, planning and leisure activities | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Speech therapy: feeding therapy if needed, speech exercises, tactile orofacial stimulation | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Education | |||||||

| Special education as needed. Develop an individualized educational plan adjusted to cognitive capacity | x | x | x | ||||

| Education for educators about the condition | x | x | x | ||||

| Craniofacial | |||||||

| Head circumference follow-up with growth curves for the age | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Otorhinolaryngology | |||||||

| Otoscopy on every visit | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Inquire about otitis media. In case of chronic otitis media, audiometry and interventions such as ventilation (PE) tubes | x | x | x | ||||

| Annual odontologic evaluation | x | x | x | x | |||

| Ophthalmology | |||||||

| Complete ophthalmologic examination | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Interventions if strabismus persists or appears | x | x | x | ||||

| glasses if needed | x | x | x | ||||

| Connective tissue abnormalities | |||||||

| Search for congenital hip dysplasia, clubfoot, or hernia | x | ||||||

| Apply Brighton criteria for joint hypermobility. If positive or if mother delays or hypotonic, offer physical therapy | x | x | x | ||||

| Orthopedic consultation if pes planus, joint instability, severe foot pronation or scoliosis is observed | x | x | x | ||||

| Cardiovascular | |||||||

| Auscultation and blood pressure testing at each consultation | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Echocardiogram if findings suggestive of mitral valve prolapse (murmur or click) | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Respiratory | |||||||

| Promote vaccination against pneumococcus and influenza | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Discourage tobacco use or illicit drugs or excessive alcohol | x | x | |||||

| Inquire for symptoms of obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome (daytime sleepiness, snoring, restless sleep). Perform polysomnography with oximetry if suspected | x | x | x | x | |||

| Gastrointestinal | |||||||

| Ask for feeding problems (vomiting, poor suck) and refer to nutrition if needed | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Promote an adequate alimentation technique: appropriate food, intake in a sitting position | x | x | x | x | |||

| Evaluate bowel habits (constipation, encopresis) toilet training and adequate wiping after stooling | x | x | x | x | |||

| Studies for gastroesophageal reflux disease and refer to gastroenterology if symptoms are present | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Genitourinary | |||||||

| Evaluate development of macroorchidism with orchidometer | x | x | |||||

| Search for inguinal hernias | x | x | x | ||||

| Evaluate the presence of enuresis | x | x | x | x | |||

| Inquire about recurrent urinary tract infection. If present, refer to urology | x | x | x | x | |||

| Endocrine | |||||||

| Measure weight and height. Follow with growth curves | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Evaluate secondary sexual characters in the search for early puberty | x | x | |||||

| Metabolic | |||||||

| Promote healthy life habits | x | x | |||||

| Family support | |||||||

| Promote community integration and Fragile X syndrome organizations | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Provide reliable and accessible information sources | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Offer cascade testing for diagnosis | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Dental health | |||||||

| Regular visits to the dentist | x | x | x | x | |||

Insomnia and other sleep problems

The prevalence of sleep disorders in individuals with Fragile X syndrome is approximately 30-50% 62 , so it is likely to be a reason for consultation in primary care. The first-line medication for the management of sleep disturbances is melatonin. Melatonin is an endogenous hormone the pineal gland produces that plays a fundamental role in circadian rhythm synchronization 63 , 64 . Additionally, it has an antioxidant effect and, in studies with animal models of Fragile X syndrome, it has been shown to improve hippocampal synaptic connectivity 65 . In patients with a poor response to melatonin, clonidine can be used as a second-line medication (Table 3). In refractory cases, management with trazodone could be initiated. It is important to note that in cases of sleep disorders, one should ask for the presence of signs and symptoms suggestive of obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome or seizures which can disturb sleep 66 .

Table 3. Medications for symptomatic management of pediatric patients with Fragile X syndrome.

| Indication | Medication | Considerations | Adverse Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep disturbances | Melatonin | First line. Extended-release formulation is more effective in individuals that wake up in the middle of the night. Give before going to sleep. | Headache, daytime sleepiness, dizziness, stomach cramps, and irritability. |

| Clonidine | Second line. In older than two years. Give before going to sleep | Headache and hypotension at high doses. Infrequent: enuresis. | |

| Trazodone | For refractory cases to melatonin and clonidine. Give before going to sleep. | Consider potential interactions with other medications. Dizziness, xerostomia, nervousness. | |

| Cannabidiol | Pharmacological presentations vary from country to country. Prefer those with fixed dosing | Tiredness, diarrhea, nausea. Drug interactions, especially if hepatic metabolism via CYP enzymes. | |

| Anxiety and related disorders | Fluoxetine Escitalopram Sertraline | First line. Sertraline is the medication with more experience in children with Fragile X syndrome. Liquid presentations if sertraline are not available in some region. | Behavioral activation, sleep disturbances, hyperactivity, aggression, impulsive behavior (especially fluoxetine). Risk of suicidal ideation and behavior, especially in adolescents. |

| Trazodone | Consider in patients with sleep disturbances, depression, aggressiveness. | See above | |

| Bupropion | Contraindicated in patients with uncontrolled seizures. Does not cause weight gain. | Reduces seizure threshold at high doses. | |

| Cannabidiol | See above | See above | |

| Attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder and associated symptoms | Psychostimulants: Methylphenidate Amphetamine derivates | Secondary effects are dose-dependent. In patients ≤4 years old with poor tolerance, suspend and reinitiate at an older age. | Decreased appetite, sleep disturbances, perseveration, tics. At high doses: decrease in language, emotional lability, irritability, and agitation. Hypertension, tachycardia |

| Clonidine | Can be given in combination with psychostimulants. Hyperactivity management. Does not improve concentration. May improve tics. May improve sleep disturbances if administered at night. | Sedation | |

| Guanfancine | Can be given in children under 5yo and later in combination with psychostimulants. Less sedation than clonidine. | ||

| L-acetylcarnitine (LAC) | Positive effect in impulsive behavior and hyperactivity. | ||

| Aggression and self injurious behavior | Aripiprazole | Response rate 70% | Irritability, perseverative behavior, weight gain, dystonia |

| Risperidone | Reserved for severe cases. Administer at night. In the case of dystonia, reduce the dose or consider concomitant use of benztropine. | Sedation. Weight gain. Dystonia. Orthostatic hypotension. Parkinsonian symptoms in older patients. | |

| Quetiapine | Quetiapine is the preferred antipsychotic in older patients because less Parkinsonism. May cause significant weight gain, especially in Prader-Willi phenotype | Weight gain, sedation, dystonia | |

| Olanzapine | |||

| SSRI | Use as adjuvant in patients with aggression and anxiety associated | See above | |

| Mood stabilizers | May be used in combination with atypical antipsychotics and behavioral interventions | Weight gain | |

| Valproate | Steven-Johnson Syndrome | ||

| Lamotrigine | Kidney disease | ||

| Lithium | Hypothyroidism |

Anxiety and associated disorders

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) constitute the first-line medications for treating anxiety in individuals with Fragile X syndrome 67 . The drugs in this class act gradually and clinical effects are evident after one to three weeks of treatment. An important consideration when prescribing an SSRI is secondary effects and potential interaction with sleep disturbances and other common symptoms in individuals with Fragile X syndrome. In about 20% of patients with Fragile X syndrome, SSRIs may cause behavioral activation, insomnia, hyperactivity, and disinhibition 68 . These symptoms can be managed by reducing the dose or discontinuing the medication. Additionally, sertraline or escitalopram produces fewer secondary effects of this type and interfere the least in the metabolism of other medication, and thus are preferred for individuals with Fragile X syndrome and hyperactivity or impulsive behavior 69 . The most frequently used medication for managing anxiety and associated disorders in individuals with Fragile X syndrome, especially in children, is sertraline 70 , 71 . In a controlled trial of low-dose sertraline in young children ages 2 to 6 y.o. with Fragile X syndrome, sertraline improved developmental testing using the Mullen Scales of Infant Learning compared to placebo 72 . In addition, in those with autism spectrum disorder and Fragile X syndrome, there was an improvement in language also with sertraline compared to placebo 72 . Even on a passive language eye-tracking paradigm, low-dose sertraline improved receptive language testing compared to placebo in this controlled trial 73 . Therefore, low dose sertraline if often used clinically in young children with Fragile X syndrome especially if language delays or autism spectrum disorder is present.

The use of other antidepressants such as bupropion, buspirone, selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) or tricyclic antidepressants can be considered in patients with hyperactivity, behavioral activation, or sleep disturbances associated with SSRIs. These medications are frequently used as alternatives for adult patients and premutation carriers but are not commonly used in pediatric patients with Fragile X syndrome (Table 3). Trazodone can be used as an alternative for pediatric patients with Fragile X syndrome and anxiety, sleep disturbances, depression, and aggressiveness 69 , 74 . Benzodiazepines can be used in acute crises but are not indicated for long-term management because of sedating and addicting features.

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and associated symptoms

The pharmacological management of attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder in patients with Fragile X syndrome is similar to that of their peers without Fragile X syndrome. Psychostimulants are the first-line medications for the management of symptoms of attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder along with behavioral strategies. Psychostimulants are well tolerated in pediatric patients with Fragile X syndrome, especially those older than five years 70 . The children receiving psychostimulants have better academic performance than those who do not receive treatment 69 . Clonidine or guanfacine can be used in children under 5 y.o. Who are too young for stimulants, and they have a calming effect on hyperarousal. Clonidine or guanfacine can also be used in combination with psychostimulants to manage hyperactivity. Besides, clonidine or guanfacine can improve tics and, owing to the sedative effect of clonidine, it can be an option for patients with sleep disturbances 72 . Clonidine and guanfacine have shown positive effects in descriptive studies. However, there is no evidence from controlled studies in patients with Fragile X syndrome 75 . Finally, L-acetylcarnitine is an alternative in cases where psychostimulants are not feasible. This nutritional supplement was studied in Italy, where Torrioli et al. 76 , conducted a randomized clinical trial in children with Fragile X syndrome and attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder with positive results in hyperactivity and social behavior.

Aggressiveness and self-injurious behavior

The management of irritability and aggressiveness in patients with Fragile X syndrome is similar to that of patients with an autism spectrum disorder. Ideally, pharmacological management should be given in conjunction with behavioral interventions discussed later. Aripiprazole and risperidone are atypical antipsychotics approved for managing aggressiveness or irritability of autism spectrum disorder in children six years of age and older 77 . However, in cases where self-injurious and aggressive behaviors are severe and result in a risk for the caregiver and the patient, risperidone or aripiprazole can be considered from three years of age 70 . Aside from the management of irritability and aggressiveness, these medications provide therapeutic effects for other common problems in patients with Fragile X syndrome. Aripiprazole can positively affect symptoms of attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder like distractibility and hyperactivity and has an anxiolytic effect 78 . Risperidone and aripiprazole have effects like a mood stabilizer and an antipsychotic. Other atypical antipsychotics that may be valuable alternatives are quetiapine and olanzapine 69 . However, they are more associated with significant weight gain than aripiprazole or risperidone, especially olanzapine. Although these medications are associated with metabolic problems like diabetes, this is not a common secondary effect in patients with Fragile X syndrome, given that the insulin molecular pathway is upregulated 79 .

Managing aggressiveness is complex and often requires multiple medications in conjunction with behavioral interventions. Aggressiveness and self-injurious behavior are one of the most important causes of morbidity and stress in the caregiver. When there is a significant component of anxiety associated with aggression, SSRIs may help. Additionally, mood-stabilizing anticonvulsants such as valproate can also be used as adjuvants when management with atypical antipsychotics and behavioral interventions have not provided an adequate response.

Seizures

The management of seizures in Fragile X syndrome is similar to that in the general population. The patients usually have a good response to monotherapy with an anticonvulsant, and seizures resolve during childhood in most cases 75 . When seizures are suspected, the patients must be evaluated with an electroencephalogram and sometimes an MRI and be referred to pediatric neurology. The indication to initiate anticonvulsant therapy is also similar to that of the general population, however, it is best to start an anticonvulsant after one seizure since kindling with seizures happens more readily in Fragile X syndrome. The choice of an anticonvulsant is based on the patient's characteristics, comorbidities, and possible drug interactions and on the profile of secondary effects of the medication. Since most patients respond favorably, beginning with only one medication at the lowest effective dose is suggested. Phenobarbital and gabapentin should be avoided if possible as they can exacerbate behavioral problems of patients with Fragile X syndrome 70 .

Targeted treatment

The search for treatments directed to reverse the neurobiological changes in Fragile X syndrome has been an area of constant research. Although there are several promising drugs, to date, the FDA has not approved for this purpose.

Targeted treatments seem to be more beneficial if they are initiated at a younger age since they could act in the critical period of neurodevelopment. Many targeted drugs have demonstrated positive effects in the murine model and are currently in clinical studies. We will mention three drugs that we consider having the potential to be approved for patients with Fragile X syndrome: metformin, cannabidiol and the phosphodiesterase inhibitor (PDE4D) that upregulates cAMP in the mouse and in patients with Fragile X syndrome 80 . For a more detailed review of targeted treatments that are under investigation, we recommend referring to reviews dedicated to this topic 61 , 81 .

Cannabidiol

Cannabidiol (CBD), a phytocannabinoid that can stimulate endocannabinoid system signaling, could improve the dysregulation in diverse neurotransmission pathways seen in Fragile X syndrome 47 , 48 . In the brain, the endocannabinoid system is activated by the action of endogenous cannabinoids on the CB1 and CB2 receptors. In Fragile X syndrome, the endocannabinoid system's activity in the CNS is dysregulated, and its pharmacological modulation in animal models has shown improvement in areas such as cognitive function, anxiety, and seizures 48 , 82 . In humans, CBD has shown positive effects in areas affected by Fragile X syndrome, such as anxiety, language, sleep quality, and cognitive function 83 . In patients with Fragile X syndrome, some observational studies describe positive effects and good tolerability in pediatric and adult patients 47 . Recently, an experimental study of transdermally administered CBD in children with Fragile X syndrome reported significant improvement in hyperactivity, social avoidance, general anxiety, and compulsive behavior 84 . CBD has a pleiotropic action, and a recently completed controlled study in children with Fragile X syndrome (3 to 18 y.o.) demonstrated significant benefits in those with> 90% methylation but not in the overall group, including those with mosaicism. These results were recently published 85 and another phase III study is starting at multiple international sites for this topical CBD preparation.

Metformin

Metformin is a biguanide commonly used to manage type 2 diabetes mellitus since it increases insulin sensitivity. Preclinical studies in animal models of Fragile X syndrome showed positive effects of metformin at the behavioral, cognitive, and circadian cycle levels. Murine models showed that metformin decreases MMP 9 levels, normalizes the ERK signaling pathway, and normalizes eIF4E phosphorylation. These changes at the molecular level were associated with the rescue of the abnormal phenotype in fragile X knock-out mice 86 . At the clinical level, uncontrolled studies showed a positive effect after the treatment with metformin at the cognitive level, especially in language and behavior 87 - 89 . At the moment, randomized, placebo-controlled studies are being carried out to evaluate the effect of treatment with metformin in areas of language and cognition, eating disorders, and behavior in patients with Fragile X syndrome. The studies include pediatric patients from 6 years of age 45 (NCT03479476, NCT03862950).

Phosphodiesterase -4D inhibitor (BPN14770)

It has been known that levels of cAMP which produce the energy for neuronal connections, is reduced in those with Fragile X syndrome and in the mouse KO model of Fragile X syndrome. So, the recent treatment of 30 adults with Fragile X syndrome in a controlled crossover phase 2 clinical trial with a PDE4D inhibitor that raises cAMP levels in Fragile X syndrome was anticipated, and the results were very exciting 80 . In this clinical trial (NCT03569631) the PDE4D inhibitor, BPN14770, improved the primary outcome measure, specifically performance on the NIH toolbox, which measures cognition after 12 weeks of treatment. Oral reading recognition, picture vocabulary and the Cognition Crystallized Composite score in addition to 'parent's rating scales for language and daily functioning, all significantly improved on the PDE4D inhibitor compared to the placebo 80 . These results in adult patients have stimulated interest in studies for children and more adults which are scheduled to take place beginning in 2022.

The future looks bright for using new targeted treatments in Fragile X syndrome and, eventually, the use of gene therapy or stem cell treatments in Fragile X syndrome because of the use of CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing that is transforming the treatment of many monogenetic disorders.

Conclusion

In recent years, significant progress has been made in understanding Fragile X syndrome. The understanding of the molecular processes that involve the FMR1 gene, the production of FMRP and the interatomic of this protein and its relationship with the phenotype has led to the identification of therapeutic targets. As new treatments are developed, multimodality interventions, including psychopharmacology, therapies, and particular education approaches, will significantly benefit the family and the child with Fragile X syndrome; this article provides a series of specific interventions according to the age of the child with Fragile X syndrome. The classic phenotype in Fragile X syndrome is observed in adults and only is established at the end of adolescence. Therefore, Fragile X syndrome should be considered a potential etiology in every child with autism spectrum disorder and neurodevelopment disorders, regardless of the age. The first step to treatment is ordering the fragile X DNA test and identifying the patient and family members who may be affected by this mutation.

Acknowledgment:

We thank the children and their families, who kindly allowed us to use their photographs. The authors received no funding.

References

- 1.Saldarriaga W, Tassone F, González-Teshima LY, Forero-Forero JV, Ayala-Zapata S, Hagerman R. Fragile X syndrome. Colomb Med (Cali) 2014;45(4):190–198. doi: 10.25100/cm.v45i4.1810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hagerman R, Hoem G, Hagerman P. Fragile X and autism Intertwined at the molecular level leading to targeted treatments. Mol Autism. 2010;1(1):12–12. doi: 10.1186/2040-2392-1-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramírez-Cheyne JA, Duque GA, Ayala-Zapata S, Saldarriaga-Gil W, Hagerman P, Hagerman R. Fragile X syndrome and connective tissue dysregulation. Clin Genet. 2019;95(2):262–267. doi: 10.1111/cge.13469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hinds HL, Ashley CT, Sutcliffe JS, Nelson DL, Warren ST, Housman DE. Tissue specific expression of FMR-1 provides evidence for a functional role in fragile X syndrome. Nat Genet. 1993;3(1):36–43. doi: 10.1038/ng0193-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bagni C, Tassone F, Neri G, Hagerman R. Fragile X syndrome causes, diagnosis, mechanisms, and therapeutics. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(12):4314–4322. doi: 10.1172/JCI63141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finucane B, Abrams L, Cronister A, Archibald AD, Bennett RL, McConkie-Rosell A. Genetic counseling and testing for FMR1 gene mutations practice guidelines of the national society of genetic counselors. J Genet Couns. 2012;21(6):752–760. doi: 10.1007/s10897-012-9524-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown SSG, Stanfield AC. Fragile X premutation carriers A systematic review of neuroimaging findings. J Neurol Sci. 2015;352(1-2):19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2015.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tassone F. Vol. 15, Expert Review of Molecular Diagnostics. Taylor and Francis Ltd; 2015. Advanced technologies for the molecular diagnosis of fragile X syndrome; pp. 1465–1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coffee B, Keith K, Albizua I, Malone T, Mowrey J, Sherman SL. Incidence of fragile X syndrome by newborn screening for methylated FMR1 DNA. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;85(4):503–514. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tassone F, Iong KP, Tong T-H, Lo J, Gane LW, Berry-Kravis E. FMR1 CGG allele size and prevalence ascertained through newborn screening in the United States. Genome Med. 2012;4(12):100–100. doi: 10.1186/gm401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fernandez-Carvajal I, Walichiewicz P, Xiaosen X, Pan R, Hagerman PJ, Tassone F. Screening for expanded alleles of the FMR1 gene in blood spots from newborn males in a Spanish population. J Mol Diagn. 2009;11(4):324–329. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2009.080173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rifé M, Badenas C, Mallolas J, Jiménez L, Cervera R, Maya A. Incidence of fragile X in 5,000 consecutive newborn males. Genet Test. 2003;7(4):339–343. doi: 10.1089/109065703322783725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sihombing NRB, Winarni TI, Utari A, van Bokhoven H, Hagerman RJ, Faradz SM. Surveillance and prevalence of fragile X syndrome in Indonesia. Intractable rare Dis Res. 2021;10(1):11–16. doi: 10.5582/irdr.2020.03101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oudet C, von Koskull H, Nordström AM, Peippo M, Mandel JL. Striking founder effect for the fragile X syndrome in Finland. Eur J Hum Genet. 1993;1(3):181–189. doi: 10.1159/000472412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kengne Kamga K, Nguefack S, Minka K, Wonkam Tingang E, Esterhuizen A, Nchangwi Munung S, et al. Cascade Testing for Fragile X Syndrome in a Rural Setting in Cameroon (Sub-Saharan Africa) Genes (Basel) 2020;11(2):136–136. doi: 10.3390/genes11020136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alfaro Arenas R, Rosell Andreo J, Heine Suñer D. Fragile X syndrome screening in pregnant women and women planning pregnancy shows a remarkably high FMR1 premutation prevalence in the Balearic Islands. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2016;171(8):1023–1031. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saldarriaga W, Forero-Forero JV, González-Teshima LY, Fandiño-Losada A, Isaza C, Tovar-Cuevas JR. Genetic cluster of fragile X syndrome in a Colombian district. J Hum Genet. 2018;63(4):509–516. doi: 10.1038/s10038-017-0407-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hunter J, Rivero-Arias O, Angelov A, Kim E, Fotheringham I, Leal J. Epidemiology of fragile X syndrome a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Med Genet A. 2014;164A(7):1648–1658. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Puusepp H, Kahre T, Sibul H, Soo V, Lind I, Raukas E. Prevalence of the fragile X syndrome among Estonian mentally retarded and the entire children's population. J Child Neurol. 2008;23(12):1400–1405. doi: 10.1177/0883073808319071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kähkönen M, Alitalo T, Airaksinen E, Matilainen R, Launiala K, Autio S. Prevalence of the fragile X syndrome in four birth cohorts of children of school age. Hum Genet. 1987;77(1):85–87. doi: 10.1007/BF00284720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Asthana JC, Sinha S, Haslam JS, Kingston HM. Survey of adolescents with severe intellectual handicap. Arch Dis Child. 1990;65(10):1133–1136. doi: 10.1136/adc.65.10.1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bartholomay KL, Lee CH, Bruno JL, Lightbody AA, Reiss AL. Closing the gender gap in Fragile X Syndrome review on females with FXS and preliminary research findings. Brain Sci. 2019;9(1):11–11. doi: 10.3390/brainsci9010011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reddy KS. Cytogenetic abnormalities and fragile-X syndrome in autism spectrum disorder. BMC Med Genet. 2005;6:3–3. doi: 10.1111/cge.12095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Winarni TI, Utari A, Mundhofir FEP, Hagerman RJ, Faradz SMH. Fragile X syndrome: clinical, cytogenetic and molecular screening among autism spectrum disorder children in Indonesia. Clin Genet. 2013;84(6):577–580. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-6-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Monaghan KG, Lyon E, Spector EB. ACMG Standards and Guidelines for fragile X testing a revision to the disease-specific supplements to the Standards and Guidelines for Clinical Genetics Laboratories of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics. Genet Med. 2013;15(7):575–586. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Handt M, Epplen A, Hoffjan S, Mese K, Epplen JT, Dekomien G. Point mutation frequency in the FMR1 gene as revealed by fragile X syndrome screening. Mol Cell Probes. 2014;28(5-6):279–283. doi: 10.1016/j.mcp.2014.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coffee B, Ikeda M, Budimirovic DB, Hjelm LN, Kaufmann WE, Warren ST. Mosaic FMR1 deletion causes fragile X syndrome and can lead to molecular misdiagnosis a case report and review of the literature. Am J Med Genet A. 2008;146A(10):1358–1367. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sitzmann AF, Hagelstrom RT, Tassone F, Hagerman RJ, Butler MG. Rare FMR1 gene mutations causing fragile X syndrome A review. Am J Med Genet A. 2018;176(1):11–18. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.38504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saldarriaga W, Payán-Gómez C, González-Teshima LY, Rosa L, Tassone F, Hagerman RJ. Double Genetic Hit Fragile X Syndrome and Partial Deletion of Protein Patched Homolog 1 Antisense as Cause of Severe Autism Spectrum Disorder. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2020;41(9):724–728. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kraan CM, Godler DE, Amor DJ. Epigenetics of fragile X syndrome and fragile X-related disorders. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2019;61(2):121–127. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.13985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Naumann A, Hochstein N, Weber S, Fanning E, Doerfler W. A Distinct DNA-Methylation Boundary in the 5'- Upstream Sequence of the FMR1 Promoter Binds Nuclear Proteins and Is Lost in Fragile X Syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;85(5):606–616. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coffee B, Zhang F, Warren ST, Reines D. Acetylated histones are associated with FMR1 in normal but not in fragile X -syndrome cells. Nat Genet. 1999;22:98–101. doi: 10.1038/8807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saldarriaga W, González-Teshima LY, Forero-Forero JV, Tang H-T, Tassone F. Mosaicism in Fragile X syndrome: A family case series. J Intellect Disabil. 2021;26(3):800–807. doi: 10.1177/1744629521995346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Godler DE, Inaba Y, Shi EZ, Skinner C, Bui QM, Francis D. Relationships between age and epi-genotype of the FMR1 exon 1/intron 1 boundary are consistent with non-random X-chromosome inactivation in FM individuals, with the selection for the unmethylated state being most significant between birth and puberty. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22(8):1516–1524. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khalfallah O, Jarjat M, Davidovic L, Nottet N, Cestèle S, Mantegazza M. Depletion of the Fragile X Mental Retardation Protein in Embryonic Stem Cells Alters the Kinetics of Neurogenesis. Stem Cells. 2017;35(2):374–385. doi: 10.1002/stem.2505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Richter JD, Zhao X. The molecular biology of FMRP new insights into fragile X syndrome. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2021;22(4):209–222. doi: 10.1038/s41583-021-00432-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dionne O, Corbin F. Vol. 10, Biology. 2021. An ""Omic"" Overview of Fragile X Syndrome. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Korb E, Herre M, Zucker-Scharff I, Gresack J, Allis CD, Darnell RB. Excess Translation of Epigenetic Regulators Contributes to Fragile X Syndrome and Is Alleviated by Brd4 Inhibition. Cell. 2017;170(6):1209–1223. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bassell GJ, Warren ST. Fragile X syndrome loss of local mRNA regulation alters synaptic development and function. Neuron. 2008;60(2):201–214. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Banerjee A, Ifrim MF, Valdez AN, Raj N, Bassell GJ. Aberrant RNA translation in fragile X syndrome From FMRP mechanisms to emerging therapeutic strategies. Brain Res. 2018;1693(A):24–36. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2018.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Portera-Cailliau C. Which comes first in fragile X syndrome, dendritic spine dysgenesis or defects in circuit plasticity. Neurosci a Rev J bringing Neurobiol Neurol psychiatry. 2012;18(1):28–44. doi: 10.1177/1073858410395322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Janusz A, Milek J, Perycz M, Pacini L, Bagni C, Kaczmarek L. The Fragile X mental retardation protein regulates matrix metalloproteinase 9 mRNA at synapses. J Neurosci. 2013;33(46):18234–18241. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2207-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bear MF, Huber KM, Warren ST. The mGluR theory of fragile X mental retardation. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27(7):370–377. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miller LJ, McIntosh DN, McGrath J, Shyu V, Lampe M, Taylor AK. Electrodermal responses to sensory stimuli in individuals with fragile X syndrome a preliminary report. Am J Med Genet. 1999;83(4):268–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Salcedo-Arellano MJ, Cabal-Herrera AM, Punatar RH, Clark CJ, Romney CA, Hagerman RJ. Overlapping Molecular Pathways Leading to Autism Spectrum Disorders, Fragile X Syndrome, and Targeted Treatments. Neurother J Am Soc Exp Neurother. 2021;18(1):265–283. doi: 10.1007/s13311-020-00968-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Parikshak NN, Luo R, Zhang A, Won H, Lowe JK, Chandran V. Integrative Functional Genomic Analyses Implicate Specific Molecular Pathways and Circuits in Autism. Cell. 2013;155(5):1008–1021. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.10.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tartaglia N, Bonn-Miller M, Hagerman R. Treatment of Fragile X Syndrome with Cannabidiol A case series study and brief review of the literature. Cannabis cannabinoid Res. 2019;4(1):3–9. doi: 10.1089/can.2018.0053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zieba J, Sinclair D, Sebree T, Bonn-Miller M, Gutterman D, Siegel S. Cannabidiol (CBD) reduces anxiety-related behavior in mice via an FMRP-independent mechanism. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2019;181:93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2019.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hagerman RJ, Berry-Kravis E, Hazlett HC, Bailey DB, Moine H, Kooy RF. Fragile X syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2017;3:17065–17065. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gross C, Hoffmann A, Bassell GJ, Berry-Kravis EM. Therapeutic Strategies in Fragile X Syndrome From Bench to Bedside and Back. Neurother J Am Soc Exp Neurother. 2015;12(3):584–608. doi: 10.1007/s13311-015-0355-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rajaratnam A, Shergill J, Salcedo-Arellano M, Saldarriaga W, Duan X, Hagerman R. Fragile X syndrome and fragile X-associated disorders. F1000Research. 2017;6:2112–2112. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.11885.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Musumeci SA, Hagerman RJ, Ferri R, Bosco P, Dalla Bernardina B, Tassinari CA. Epilepsy and EEG findings in males with fragile X syndrome. Epilepsia. 1999;40(8):1092–1099. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1999.tb00824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Heard TT, Ramgopal S, Picker J, Lincoln SA, Rotenberg A, Kothare S V. EEG abnormalities and seizures in genetically diagnosed Fragile X syndrome. Int J Dev Neurosci Off J Int Soc Dev Neurosci. 2014;38:155–160. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2014.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ciaccio C, Fontana L, Milani D, Tabano S, Miozzo M, Esposito S. Fragile X syndrome: a review of clinical and molecular diagnoses. Ital J Pediatr. 2017;43(1):39–39. doi: 10.1186/s13052-017-0355-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.de Vries BB, Wiegers AM, Smits AP, Mohkamsing S, Duivenvoorden HJ, Fryns JP. Mental status of females with an FMR1 gene full mutation. Am J Hum Genet. 1996;58(5):1025–1032. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kaufmann WE, Kidd SA, Andrews HF, Budimirovic DB, Esler A, Haas-Givler B. Autism Spectrum Disorder in Fragile X Syndrome Cooccurring Conditions and Current Treatment. Pediatrics. 2017;139(Suppl 3):S194–S206. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1159F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bailey DBJ, Raspa M, Olmsted M, Holiday DB. Co-occurring conditions associated with FMR1 gene variations findings from a national parent survey. Am J Med Genet A. 2008;146A(16):2060–2069. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hall SS, Lightbody AA, Reiss AL. Compulsive, self-injurious, and autistic behavior in children and adolescents with fragile X syndrome. Am J Ment Retard. 2008;113(1):44–53. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2008)113[44:CSAABI]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Moeschler JB, Shevell M. Comprehensive evaluation of the child with intellectual disability or global developmental delays. Pediatrics. 2014;134(3):e903–e918. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-1839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hyman SL, Levy SE, Myers SM. Identification, Evaluation, and management of children with autism spectrum disorder. Pediatrics. 2020;145(1):e20193447. doi: 10.1542/9781610024716-part01-ch002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Protic D, Salcedo-Arellano MJ, Dy JB, Potter LA, Hagerman RJ. New targeted treatments for Fragile X Syndrome. Curr Pediatr Rev. 2019;15(4):251–258. doi: 10.2174/1573396315666190625110748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kidd SA, Lachiewicz A, Barbouth D, Blitz RK, Delahunty C, McBrien D. Fragile X syndrome A review of associated medical problems. Pediatrics. 2014;134(5):995–1005. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-4301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Goldman SE, Adkins KW, Calcutt MW, Carter MD, Goodpaster RL, Wang L. Melatonin in children with autism spectrum disorders endogenous and pharmacokinetic profiles in relation to sleep. J Autism Dev Disord. 2014;44(10):2525–2535. doi: 10.1007/s10803-014-2123-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wu Z, Huang S, Zou J, Wang Q, Naveed M, Bao H. Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) Disturbance of the melatonin system and its implications. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;130:110496–110496. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Won J, Jin Y, Choi J, Park S, Lee T, Lee S-R. Melatonin as a Novel Interventional Candidate for Fragile X Syndrome with Autism Spectrum Disorder in Humans. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(6):1314–1314. doi: 10.3390/ijms18061314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hamlin A, Liu Y, Nguyen D V, Tassone F, Zhang L, Hagerman RJ. Sleep apnea in fragile X premutation carriers with and without FXTAS. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2011/09/19. 2011;156B(8):923–928. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.31237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hanson AC, Hagerman RJ. Serotonin dysregulation in Fragile X Syndrome implications for treatment. Intractable Rare Dis Res. 2014;3(4):110–117. doi: 10.5582/irdr.2014.01027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kolevzon A, Mathewson KA, Hollander E. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in autism. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(03):407–414. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v67n0311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Berry-Kravis E, Sumis A, Hervey C, Mathur S. Clinic-based retrospective analysis of psychopharmacology for behavior in Fragile X Syndrome. Int J Pediatr. 2012;2012:1–11. doi: 10.1155/2012/843016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hagerman RJ, Berry-Kravis E, Kaufmann WE, Ono MY, Tartaglia N, Lachiewicz A. Advances in the treatment of Fragile X Syndrome. Pediatrics. 2009;123(1):378–390. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Greiss Hess L, Fitzpatrick SE, Nguyen D V, Chen Y, Gaul KN, Schneider A. A Randomized, Double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of low-dose sertraline in young children with Fragile X Syndrome. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2016;37(8):619–628. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Relia S, Ekambaram V. Pharmacological approach to sleep disturbances in autism spectrum disorders with psychiatric comorbidities a literature review. Med Sci. 2018;6(4):95–95. doi: 10.3390/medsci6040095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yoo KH, Burris JL, Gaul KN, Hagerman RJ, Rivera SM. Low-dose sertraline improves receptive language in children with Fragile X Syndrome when eye tracking methodology is used to measure treatment outcome. J Psychol Clin Psychiatry. 2017;7(6) doi: 10.15406/jpcpy.2017.07.00465. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ghaziuddin N, Alessi NE. An open clinical trial of trazodone in aggressive children. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 1992;2(4):291–297. doi: 10.1089/cap.1992.2.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lozano R, Azarang A, Wilaisakditipakorn T, Hagerman RJ. Fragile X syndrome A review of clinical management. Intractable rare Dis Res. 2016;5(3):145–157. doi: 10.5582/irdr.2016.01048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Torrioli MG, Vernacotola S, Peruzzi L, Tabolacci E, Mila M, Militerni R. A double-blind, parallel, multicenter comparison ofL-acetylcarnitine with placebo on the attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in fragile X syndrome boys. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2008;146A(7):803–812. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Erickson C, Srivorakiat L, Wink L, Pedapati E, Fitzpatrick S. Aggression in autism spectrum disorder: presentation and treatment options. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:1525–1538. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S84585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Erickson CA, Stigler KA, Wink LK, Mullett JE, Kohn A, Posey DJ. A prospective open-label study of aripiprazole in fragile X syndrome. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011;216(1):85–90. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2194-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Drozd M, Bardoni B, Capovilla M. Modeling Fragile X Syndrome in Drosophila. Front Mol Neurosci. 2018;11:124–124. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2018.00124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Berry-Kravis EM, Harnett MD, Reines SA, Reese MA, Ethridge LE, Outterson AH. Inhibition of phosphodiesterase-4D in adults with fragile X syndrome a randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 2 clinical trial. Nat Med. 2021;27(5):862–870. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01321-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tassanakijpanich N, Cabal-Herrera AM, Salcedo-Arellano MJ, Hagerman RJ. Fragile X Syndrome and targeted treatments. J Biomed Transl Res. 2020;6(1):23–33. doi: 10.14710/jbtr.v6i1.7321. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Busquets-Garcia A, Gomis-González M, Guegan T, Agustín-Pavón C, Pastor A, Mato S. Targeting the endocannabinoid system in the treatment of fragile X syndrome. Nat Med. 2013;19(5):603–607. doi: 10.1038/nm.3127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bergamaschi MM, Queiroz RHC, Chagas MHN, de Oliveira DCG, De Martinis BS, Kapczinski F. Cannabidiol reduces the anxiety induced by simulated public speaking in treatment-naïve social phobia patients. Neuropsychopharmacol Off Publ Am Coll Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;36(6):1219–1226. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Heussler H, Cohen J, Silove N, Tich N, Bonn-Miller MO, Du W. A phase 1/2, open-label assessment of the safety, tolerability, and efficacy of transdermal cannabidiol (ZYN002) for the treatment of pediatric fragile X syndrome. J Neurodev Disord. 2019;11(1):16–16. doi: 10.1186/s11689-019-9277-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Berry-Kravis E, Hagerman R, Budimirovic D, Erickson C, Heussler H, Tartaglia N, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of ZYN002 cannabidiol transdermal gel in children and adolescents with fragile X syndrome (CONNECT-FX) J Neurodev Disord. 2022;14(1):56–56. doi: 10.1186/s11689-022-09466-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gantois I, Khoutorsky A, Popic J, Aguilar-Valles A, Freemantle E, Cao R. Metformin ameliorates core deficits in a mouse model of fragile X syndrome. Nat Med. 2017;23(6):674–677. doi: 10.1038/nm.4335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Dy ABC, Tassone F, Eldeeb M, Salcedo-Arellano MJ, Tartaglia N, Hagerman R. Metformin as targeted treatment in fragile X syndrome. Clin Genet. 2018;93(2):216–222. doi: 10.1111/cge.13039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Protic D, Aydin EY, Tassone F, Tan MM, Hagerman RJ, Schneider A. Cognitive and behavioral improvement in adults with fragile X syndrome treated with metformin-two cases. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2019;7(7):e00745. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Biag HMB, Potter LA, Wilkins V, Afzal S, Rosvall A, Salcedo-Arellano MJ, et al. Metformin treatment in young children with fragile X syndrome. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2019;7(11) doi: 10.1002/mgg3.956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lachiewicz AM, Dawson D V, Spiridigliozzi GA. Physical characteristics of young boys with fragile X syndrome: reasons for difficulties in making a diagnosis in young males. Am J Med Genet. 2000;92(4):229–236. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(20000605)92:4<229::aid-ajmg1>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hagerman RJ, Staley LW, 'O'Conner R, Lugenbeel K, Nelson D, McLean SD, et al. Learning-disabled males with a fragile X CGG expansion in the upper premutation size range. Pediatrics. 1996;97(1):122–126. doi: 10.1542/peds.97.1.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]