Abstract

This present work provides the initial co-efficient bounds of the function f(z) which is defined in open unit disk . We introduced bi-univalent class . Making use of Horadam polynomials and the generating function , we estimated the bounds of and for the given function to be in the defined class. Moreover Fekete-Szego inequalities are calculated. In addition to all the results obtained mathematically, we provide application for Horadam polynomial in computer vision.

Subject terms: Engineering, Mathematics and computing

Introduction

A function f belonging to the class is analytic in open unit disk . Where the class contains all analytic functions of the form

| 1 |

While a subclass contains all univalent functions in open unit disk . Every function has an inverse which is defined as and , ,

where

| 2 |

A bi-univalent function is a complex-valued function that is both bijective and univalent in the open unit disk of the complex plane. In other words, a bi-univalent function is a function that maps the open unit disk onto a bijective image in the complex plane, such that the function is one-to-one and has a single-valued inverse function in the open unit disk.

More formally, a function f(z) is bi-univalent in the open unit disk if and only if:

f(z) is analytic and injective in the open unit disk, i.e., for any two distinct points and in the open unit disk, does not equal .

f(z) maps the open unit disk onto a bijective image, i.e., for every point w in the image, there exists a unique point z in the open unit disk such that .

The inverse function is also analytic and injective in the image of f(z).

Bi-univalent functions have been studied extensively in complex analysis and geometric function theory due to their properties and applications in various fields such as mathematical physics, engineering, and image processing. One of the fundamental results related to bi-univalent functions is the Bieberbach conjecture, which states that the Taylor coefficients of a bi-univalent function in the open unit disk satisfy certain inequalities. This conjecture was proved by Louis de Branges in 1985, and it has many important consequences in complex analysis. Examples of bi-univalent functions include the Koebe function, the Bessel function, and various subclasses of bi-univalent functions such as starlike and convex functions.

Precisely if a function and its inverse are univalent in then the function f is said to be bi-univalent in . Let is the symbol of the class of bi-univalent functions in of the form (1)

Definition 1

Starlike functions1 A simple connected domain is supposed to be starlike with regard to , if there exists a line segment which joins to any other point of and it completly lies in .

Suppose is claimed to be star-like function relevant to the origin, if u maps the unit disk onto a star-like domain in view of the origin. The family denotes the collection of all star-like functions in view of origin.

Equivalently,

Definition 2

Convex functions (Goodman 1983) In a complex plane , a domain is supposed to be convex if it is star-like concerning each of its points, (i.e) if every pair of points of can be joined by a line segment, which completly lies in .

A function is claimed to be a convex function if u maps the unit disk onto a convex domain. The family indicates the collection of all convex functions.

Equivalently,

Recently Srivastava et al.2 have studied analytic and bi-univalent functions. Many authors have studied and provided various subclasses of bi-univalent functions and fixed the initial co-efficients and [see3–8 and9].

For two analytic functions f(z) and g(z) , if f(z) subordinate to g(z) and it can be written as if there exists a Schwartz function w with and such that . It is well known that the function g is univalent in then and

The Horadam polynomials are defined by the following relation (see10),

with

| 3 |

where are real constants.

The generating function of the Horadam polynomials (see11) is given by

| 4 |

Frasin12 investigated the inequalities of co-efficient for certain classes of generalized Sakaguchi type function f satisfying the following geometrical property

| 5 |

s, t are complex numbers with and .

For the fixed values of and the Horadam polynomial provides various types of polynomials, from these, we have listed a few here (see13– 21):

When , we have the Lucas polynomial

When , we have the Fibonacci polynomial

When , we arrive the pell-Lucas polynomials

When , we reaches the pell polynomial

When and , we have the chebyshev polynomials of the second kind.

When and , we get the chebyshev polynomials of the first kind.

Definition 3

A function is said to be in the class if it satisfies the following subordination conditions which are follows,

and

where , with , and a is a real constant, the function is given by (2).

Special Case:1 For the class is reduced to satisfying the following conditions

and

Special Case:2 For the case in the class reduces to the class satisfying the following conditions,

and

Main results

Theorem 4

A function be in the class , then

where

Proof

Let .

Let the function and are analytic in . given by

| 6 |

| 7 |

with

such that

and

which is equivalently,

| 8 |

and

| 9 |

Joining (6), (7) ,(8) and (9), gives

| 10 |

and

| 11 |

we know that if and ,

| 12 |

Equate like co-efficients in (10) and (11), and simplifying,

we get

| 13 |

| 14 |

| 15 |

| 16 |

| 17 |

Squaring and adding (13) and (15), we have

| 18 |

By adding (14) and (16) , we have

| 19 |

By Making use of (15) it is reduced that

| 20 |

using equations (3) and (12) in (20), we obtain

Difference between (14) and (16), follows that

| 21 |

By (17) and (18) we have from (21)

Using (3), we get

This completes the proof of the theorem (4).

If we take in Theorem 4, we obtain the following corollary,

Corollary 5

A function and of the form (1) is in the class , then

Remark 6

When ,The class is reduced to the class .

Theorem 7

For any complex number , Let be in the class then

where

and

Proof

where

Hence, we have

For and in Theorem (7), the following co-efficient estimates is obtained.

Corollary 8

A function and of the form (1) is in the class , then

Application

The Horadam polynomial is an illustration of a mathematical sequence used in texture analysis and image processing. The Horadam polynomial, a specific kind of polynomial sequence, can be used to perform procedures like filtering and resampling. In image processing and computer vision, scale-space representations of images can be created and modified using the Horadam polynomial. This polynomial can be used for edge identification, texture analysis, and multi-scale image analysis. About texture analysis, the Horadam polynomial has been used for feature extraction, segmentation, and picture denoising. This technique can be used to analyze the statistical properties of textures, including the distribution of gray levels and the spatial organization of textures.

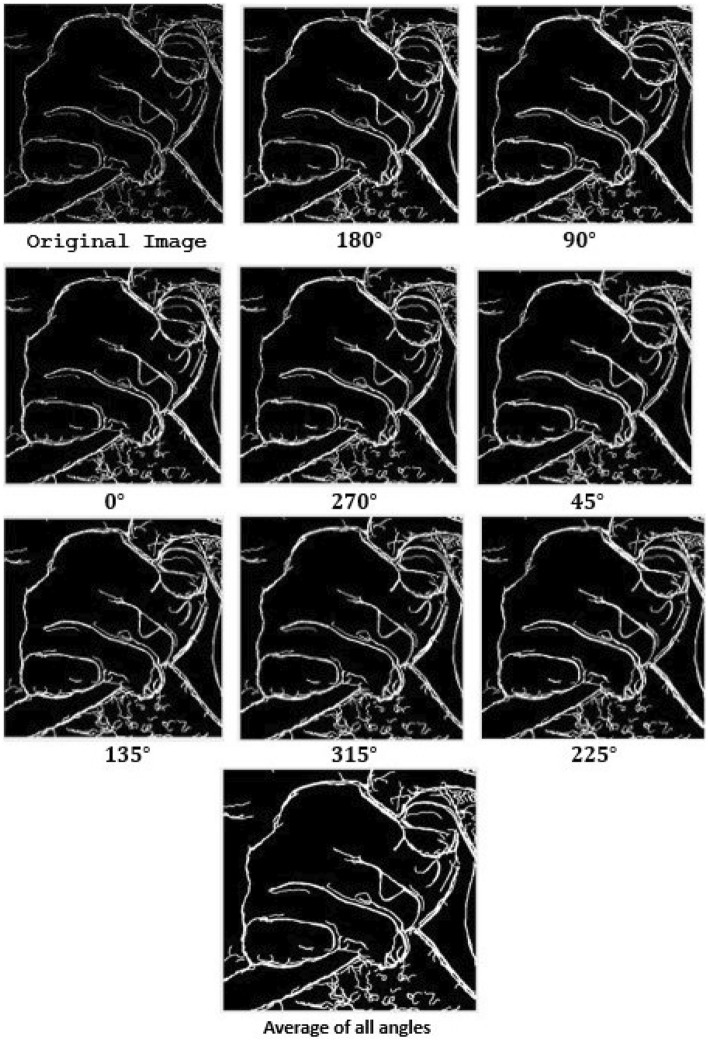

This article focuses on texture analysis utilizing canny images by convoluting the calculated co-efficient values to the image pixels using masking at eight different angles and displaying the best result.

The image used to comprehend is a closed palm image of resolution 600600. The original image and its corresponding Hist Value are shown in the Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Canny Image of the closed palm using Edge detection algorithm.

Elucidation

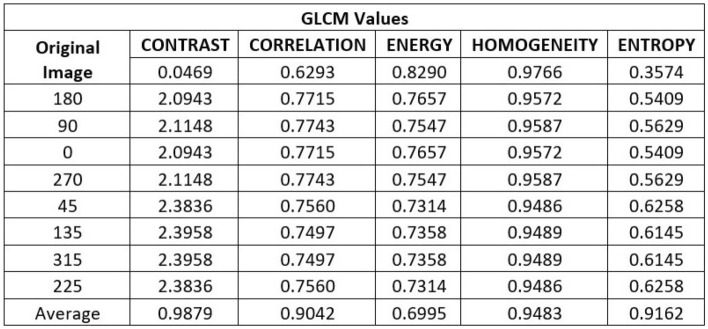

Figure 2 displays the GLCM values for the canny image at various angles. The tabulation also shows that the Horadam polynomial examines the texture of the supplied image and that the values are also quite good for the contrast, correlation, energy, homogeneity, and entropy requirements. The suggested Texture method thus yields superior outcomes. The results of the image taken at various angles are shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 2.

Representation of Gray-Level Co-Occurrence Matrix (GLCM) values obtained by MATLAB.

Figure 3.

The original Image is the canny image of a closed palm, using the quality metrics, contrast, correlation, entropy, energy, and homogeneity. Above images show the canny image of the same at angles of , respectively, with increased contrast, correlation, and entropy and decreased energy and homogeneity. The final figure shows a canny representation of the average of the aforementioned angles along with the relevant metrics.

Conclusion

The goal of the manuscript was to link geometric function theory and image processing, specifically texture analysis. The image selected is solely a canny image, and it is treated using the outcomes of the work’s mathematical analysis, the study is justified by the obtained values of the metrics utilised, such as contrast, correlation, entropy, energy, and homogeneity. The work also sheds lime light to work with coloured images and investigate various image-processing techniques like enhancement, sharpening, pattern identification, restoration, and retrieval. Mathematically future research can be carried out with the results of Fekete inequality obtained for inverse functions and can be applied in image processing.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to the referees for their useful comments.

Author contributions

H.P. Verifying the model with visual representation using MATLAB. B.S. Identifying the problem and developing a methodology. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Data availability

Image source file for Canny image is given below: Closed PalmThe MATLAB code used in this investigation are accessible through the following link MATLAB CODE-Mendeley Data BHASKARA, SRUTHAKEERTHI; H, Priya, “Texture analysis using Horadam Polynomial coefficient estimate for the class of Sakaguchi kind function”, Mendeley Data, V1, doi: 10.17632/pw779rf4jn.1.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Goodman AW. Univalent Functions. United States: Mariner Publishing Company; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Srivastava HM, Mishra AK, Gochhayat P. Certain subclasses of analytic and Bi univalent functions. Appl. Math. Lett. 2010;23:1188–1192. doi: 10.1016/j.aml.2010.05.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frasin BA, Aouf MK. New subclasses of bi-univalent functions. Appl. Math. Lett. 2011;24:1569–1573. doi: 10.1016/j.aml.2011.03.048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goyal SP, Goswami P. Estimate for initial Maclaurin coefficients of bi-univalent functions for a class defined by fractional derivatives. J. Egyptian Math. Soc. 2012;20:179–182. doi: 10.1016/j.joems.2012.08.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Srivastava, H. M., Altinkaya, S. & Yalçin, S. Certain subclasses of bi-univalent functions associated with the Horadam polynomials, Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Sci., 1-7. (2018).

- 6.Srivastava HM, Eker SS, Ali RM. Coefficient bounds for a certain class of analytic and bi-univalent functions. Filomat. 2015;29:1839–1845. doi: 10.2298/FIL1508839S. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Srivastava HM, Eker SS, Hamidi SG, Jahangiri JM. Faber polynomial coefficient estimates for bi-univalent functions defined by the Tremblay fractional derivative operator. Bull. Iran. Math. Soc. 2018;44(1):149–157. doi: 10.1007/s41980-018-0011-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Srivastava HM, Gaboury S, Ghanim F. Coefficient estimates for some general subclasses of analytic and bi-univalent functions. Africa Math. 2017;28:693–706. doi: 10.1007/s13370-016-0478-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wanas AK, Majeed AH. Certain new subclasses of analytic and m-fold symmetric Bi univalent functions. Appl. Math. E-Notes. 2018;18:178–188. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horadam AF, Mahon JM. Pell and Pell-Lucas polynomials. Fibonacci Quart. 1985;23:7–20. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horcum T, Kocer EG. On some properties of Horadam polynomials. Int. Math. Forum. 2009;4:1243–1252. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duren PL. Univalent Functions, Grundlehren der Mathematischen Wissenschaften. New York, Berlin, Heidelberg and Tokyo: Springer Verlag; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horadam AF, Mahon JM. Pell and Pell-Lucas polynomials. Fibonacci Q. 1985;23:7–20. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hörçum T, GökçenKoçer E. On some properties of Horadam polynomials. Int. Math. Forum. 2009;4:1243–1252. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caglar M, Orhan H, Yagmur N. Coefficient bounds for new subclasses of bi-univalent functions. Filomat. 2013;27:1165–1171. doi: 10.2298/FIL1307165C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frasin BA. Coefficient inequalities for certain classes of Sakaguchi type functions. Int. J. Nonlinear Sci. 2010;10(2):206–211. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh R. On Bazilevic functions. Proc. Amer. Math. Soc. 1973;38(2):261–271. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Srivastava HM, Bansal D. Coefficient estimates for a subclass of analytic and biunivalent functions. J. Egyptian Math. Soc. 2015;23:242–246. doi: 10.1016/j.joems.2014.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wanas, A. K. & Alina, A. L. (2019) Applications of Horadam polynomials on Bazilevic bi univalent function satisfying subordinate conditions, IOP Conf. Series: J. Phys.: Conf. Series, 1294(03): 03200.

- 20.Lokesh P, Srutha Keerthi B. Horadam polynomial coefficient estimates for Sakaguchi kind of functions. Solid State Technol. 2020;63(6):2126–2137. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Balaji S, SruthaKeerthi B. Sakaguchi kind of functions and horadam polynomial Co-efficients. Solid State Technol. 2020;63(6):23042–23050. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Image source file for Canny image is given below: Closed PalmThe MATLAB code used in this investigation are accessible through the following link MATLAB CODE-Mendeley Data BHASKARA, SRUTHAKEERTHI; H, Priya, “Texture analysis using Horadam Polynomial coefficient estimate for the class of Sakaguchi kind function”, Mendeley Data, V1, doi: 10.17632/pw779rf4jn.1.