Abstract

The hedgehog state in the icosahedral quasicrystal (QC) has attracted great interest as the theoretical discovery of topological magnetic texture in aperiodic systems. The revealed magnetic dynamics exhibits nonreciprocal excitation in the vast extent of the reciprocal lattice -energy space, whose emergence mechanism remains unresolved. Here, we analyze the dynamical as well as static structure of the hedgehog order in the 1/1 approximant crystal (AC) composed of the cubic lattice with spatial inversion symmetry. We find that the dispersion of the magnetic excitation energy exhibits nonreciprocal feature along the N-P- line in the space. The dynamical structure factor exhibits highly structured intensities where high intensities appear in the high-energy branches along the -H line and the P--N line in the space. The nonreciprocity in the 1/1 AC and also in the QC is understood to be ascribed to inversion symmetry breaking by the hedgehog ordering. The sharp contrast on the emergence regime of nonreciprocal magnetic excitation between the QC and the 1/1 AC indicates that the emergence in the vast - regime in the QC is attributed to the QC lattice structure.

Subject terms: Magnetic properties and materials, Topological defects

Quasicrystal (QC) has no periodicity but possesses a unique rotational symmetry forbidden in periodic crystals1–3. In periodic crystals, the electric states can be understood on the basis of the Bloch’s theorem grounded on the translational symmetry of the lattice. In contrast, in the QC, the Bloch’s theorem can no longer be applied. This makes understanding of the electronic states and physical properties of the QC far from complete one and hence their clarifications have attracted great interest as the frontier of the condensed matter physics as well as the material science.

One of the important remaining issues has been whether the magnetic long-range order is realized in the QC. In the rare-earth based approximant crystals (AC)s which have the local atomic configuration common to that in the QC with periodicity, the magnetic long-range order was observed experimentally4. The 4f electrons at the rare-earth atom are responsible for the magnetism. The antiferromagnetic (AFM) order was observed in the 1/1 AC CdR (R=Tb, Y, Pr, Nd, Sm, Gd, Tb, Dy, Ho, Er, Tm, Yb, and Lu)5–7, and Au–Al–R (R=Gd and Tb)8, 9. The ferromagnetic (FM) order was observed in the 1/1 AC Au-SM-R (SM=Si, Ge, and Al; R=Gd, Tb, Dy, and Ho)10–13. Recently, the FM long-range order has been discovered in the QC Au–Ga–Tb and Au–Ga–Gd, which has brought about the breakthrough14.

Theoretically, lack of the microscopic theory of the crystalline electric field (CEF) at the rare-earth site in the QC and AC has prevented us from understanding the strongly-correlated electron states, in particular, the properties of the magnetism. Recently, general formulation of the CEF theory in the rare-earth based QC and AC has been developed on the basis of the point charge model15. This allows us to reveal that the magnetic anisotropy arising from the CEF at the rare-earth site plays a crucial role in realizing unique magnetic structures16, 17. Recent theoretical analyses of the effective model taking into account the magnetic anisotropy in the QC Au–SM–Tb have shown that the uniform FM state is stabilized, which provides a candidate for the magnetic structure observed recently in the QC Au–Ga–Tb17. Moreover, interestingly enough, uniform hedgehog state has theoretically been shown to be stabilized in the QC16. The hedgehog state is the topological magnetic texture whose magnetic moments located at the 12 vertices of the icosahedron (IC) are directed outward from the IC as shown in Fig. 1A, which is characterized by the topological charge 16.

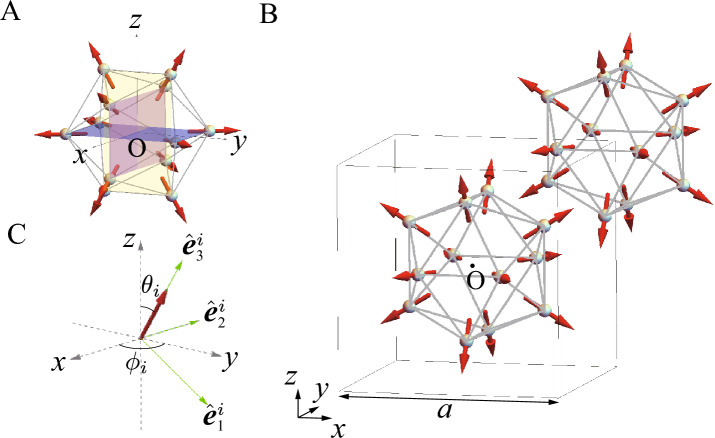

Figure 1.

(A) The hedgehog state in the IC, where the magnetic moments (red arrows) are directed outward from the IC to the 5-fold axis direction. The rectangle in the IC is colored in purple, pink, and yellow (see text). (B) Uniform hedgehog order at the center and corner of the bcc unit cell in the 1/1 AC. The box frame is the cubic unit cell with the side length a. (C) Local coordinate at the Tb site with the orthogonal unit vectors , , and where is directed to the magnetic easy axis arising from the CEF (see text). (This figure is created by using Adobe Illustrator CS5 Version 15.1.0.).

Recently, the magnetic dynamics of the uniform hedgehog order in the QC has for the first time been studied theoretically18. It has been revealed that the nonreciprocal excitation appears in the vast extent of the reciprocal lattice -energy space. Namely, the dynamical structure factor has been shown to have different values for the reciprocal lattice vector in the opposite direction, i.e., . In this report, to get insight into the nonreciprocal excitation, we analyze the dynamical as well as static structures of the uniform hedgehog order in the 1/1 AC.

It is remarked here that the dynamics of the topological magnetic textures20 and the nonreciprocal magnetic excitation21 has attracted much attention nowadays in periodic crystals22. In non-centrosymmetric systems, the Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya interaction for the magnetic moments is known to cause the nonreciprocal excitations23–31. The nonreciprocal magnon was also shown to appear in centrosymmetric systems32–36. Recently, the nonreciprocal excitation has been found in the Skyrmion crystal on the centrosymmetric lattice21, whose mechanism has not been fully understood. Therefore, the present study contributes to the understanding of the nonreciprocal excitations in the topological magnetic textures on centrosymmetric systems.

Results

Lattice structure of the IC and 1/1 AC

We consider the lattice structure of the 1/1 AC identified experimentally in the AuSiTb13. The IC is located at the center and the corner of the body-center-cubic (bcc) unit cell with the lattice constant , as shown in Fig. 1B. The crystal structure is cubic (Space Group No. 204, , ), which retains the spatial inversion symmetry.

The hedgehog state in the IC is regarded as the superposition of the coplanar alignment in the three layers orthogonal each other as shown as the purple, pink, and yellow rectangles in Fig. 1A. Each rectangle has the side length and . As for the direction of the magnetic moments, we consider that each moment is directed to the 5-fold axis (but not the pseudo 5-fold axis on the distorted IC) whose direction is given by the vector passing through each vertex of the regular IC from the center. Namely, the magnetic moment at each vertex of the rectangle in Fig. 1A is given by for the , 3, 11, and 12th site (purple rectangle), for the , 6, 8, and 9th site (pink rectangle), and for the , 4, 7, and 10th site (yellow rectangle). Here, S is the magnitude of the total angular momentum, which is referred to as “spin” hereafter, and is the golden mean .

Minimal model for magnetism in rare earth based QC and AC

We employ the minimal model for the rare earth-based QC and AC introduced in Ref.19:

| 1 |

where is the “spin” operator at the ith Tb site with and is the exchange interaction for the “spins” at the ith and jth Tb sites. The second term represents the magnetic anisotropy arising from the CEF, where is the unit vector along the magnetic easy axis arising from the CEF as shown in Fig. 1C (see Section “Methods” for detail). This model is considered to be effective for broad range of the rare earth-based QC and AC, which is not only restricted to the Tb-based system but also is applied to the other rare-earth-based QC and AC.

The ground-state phase diagram of the model (1) applied to the single IC in the large-D limit was determined by the numerical calculations for the ferromagnetic (FM) interaction17 and the antiferromagnetic (AF) interaction 16, where is the nearest neighbor (N.N.) interaction [5 bonds for each site with the bond length 0.374a (1 bond) and 0.378a (4 bonds)] and is the next nearest neighbor (N.N.N.) interaction [5 bonds for each site with the bond length 0.610a (4 bonds) and 0.612a (1 bond)]. In both cases, the hedgehog state was shown to be realized in the ground state phase diagram of . The model (1) was also applied to the 1/1 AC where the nearest neighbor (N.N.) interaction and the next N.N. (N.N.N.) interaction not only for the intra IC but also for the inter IC was considered in the large-D limit16. The intra IC interaction is the same as noted above. As for the inter IC interaction, the N.N. interaction is set to be [5 bonds for each site with bond length 0.368a (4 bonds) and 0.388a (1 bond)] and the N.N.N. interaction is set to be [6 bonds for each site with bond length 0.528a (2 bonds) and 0.530a (4 bonds)]. It was shown in Ref.17 that this minimal model for the large-D limit explains the magnetic structures of the FM order (ferrimagnet) observed in the 1/1 AC AuSiTb13 and the AFM order of whirling-moment states in the 1/1 AC AuAlTb26.

It was shown that for , the hedgehog state and anti-hedgehog state are realized at the center and corner of the bcc unit cell in the ground state16, 17. Within the linear spin-wave theory, we find that the uniform hedgehog order is realized in the 1/1 AC as metastable state although the true ground state is alternated hedgehog order as shown in Refs.16, 17. In this report, to get insight into the mechanism of the nonreciprocal magnetic excitation in the uniform hedgehog order found in the QC, we analyze the magnetic excitation in the “uniform” hedgehog state in the 1/1 AC by employing the metastable state (local minimum in the energy landscape) but not the true ground state.

Static structure factor of magnetism

First, let us analyze the magnetic structure of the uniform hedgehog ground state in the 1/1 AC. The static structure factor of magnetism is defined as

| 2 |

where N is the total number of the Tb sites. Let us rewrite the position vector of the Tb site as , where denotes the position of the center of the IC and denotes the position of the mth Tb site on the IC. The position vector of the IC is expressed as

| 3 |

where is an integer and is the basic translation vector of the bcc lattice , , and . Here, a is the lattice constant of the bcc unit cell (see Fig. 1B). The magnetic structure factor (Eq. 2) is derived to be expressed in the convolution form as

| 4 |

where the structure factor of the lattice and the magnetic structure factor on a single IC are given by

| 5 |

| 6 |

respectively. Here, is the number of the primitive unit cell which contains the single IC i.e., 12 Tb sites (note that the box frame drawn in Fig. 1B denotes the expanded unit cell which contains two ICs, i.e., 24 Tb sites) and holds. The wave vector is given by

| 7 |

where is the basic translation vector in the reciprocal lattice with , , and .

We consider the periodic boundary condition along for and 3. Then, , , and are given by , , and with integer . The structure factor of the bcc lattice of the 1/1 AC is calculated as

| 8 |

For integer and , the vector in Eq. (7) becomes the reciprocal lattice vector, i.e. , where with integer , , and . Then, we obtain . As , and deviate from the integer values, decays rapidly in the finite-size system. For the bulk limit, i.e., , becomes zero for non-integer , , and , which yields .

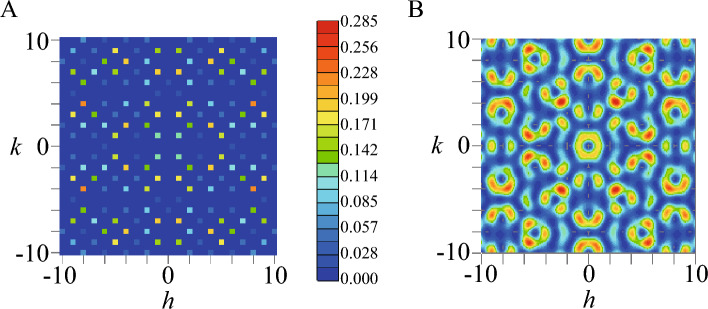

Then, it tuns out that the convolution form in Eq. (4) indicates that the vector giving is restricted to the integer values of , , and where becomes non zero. We have calculated in for where h, k, and l are defined by , , and , respectively. For , the maximum of is identified to be 0.215 at , , and . We plot for in the h-k plane in Fig. 2A. We have also calculated for in the l-h plane at and for in the k-l plane at . The results are the same as those in Fig. 2A where h and k are replaced with l and h respectively and k and l respectively. It is noted here that Eq. (4) is also applied to the QC, where is the structure factor of the QC lattice.

Figure 2.

(A) The magnetic structure factor of the 1/1 AC for in the h-k plane. (B) The magnetic structure factor of the IC for in the h-k plane. The color scale is common to that in (A). (This figure is created by using Adobe Illustrator CS5 Version 15.1.0.).

Here, to get insight into the magnetic structure on the IC, let us analyze in a single IC for general . We have searched the maximum in for . Then, the maximum appears at , , and . Figure 2B shows in the h-k plane at . We note that the analytic form of for can be derived as

| 9 |

We have also calculated for in the l-h plane at and for in the k-l plane at . The results are the same as those where h and k in Fig. 2B are replaced with l and h respectively and k and l respectively. These are understandable from the symmetry of the hedgehog shown in Fig. 1A. Namely, the alignment of the magnetic moments on the IC is invariant under the permutation of the x, y, and z axes so that the same results of are obtained by replacing with and also with 18.

Dispersion of magnetic excitation from the hedgehog ground state

To clarify the property of the magnetic excitation in the uniform hedgehog order in the 1/1 AC, we employ the linear spin-wave theory (see Section “Methods”). Namely, we apply the Holstein-Primakoff transformation37 to H, the “spin” operators are transformed to the boson operators as with , , and , where is the raising (lowering) “spin” operator and is a creation (annihilation) operator of the boson at the ith Tb site. We retain the quadratic terms of the boson operators since the higher order terms are irrelevant at least for the ground state. By taking the primitive unit cell under the periodic boundary condition, we have performed the numerical calculations in the systems with and 256, and show the results in .

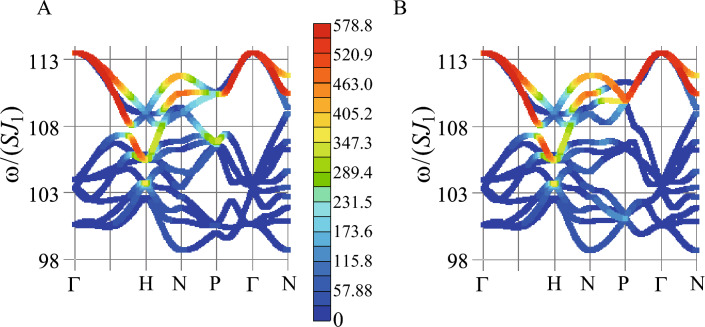

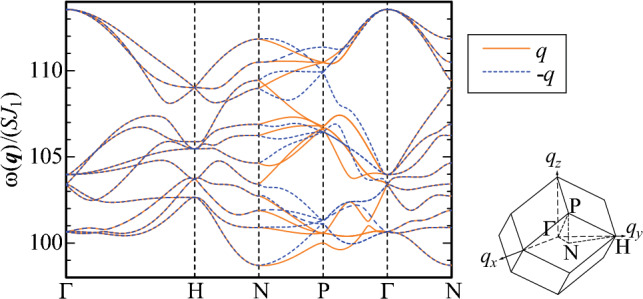

The excitation energy is obtained by diagonalizing the spin-wave Hamiltonian under the assumption that the uniform arrangement of the hedgehog state in the 1/1 AC. The result of for (solid line) along the symmetry line illustrated in the inset is shown in Fig. 3. We have confirmed that by assuming the uniform hedgehog ground state, all the excitation energies are positive for , , and as shown in Fig. 3. Positive excitation energies indicate that the assumed ground state is stable at least as a local minimum in the energy landscape. Although the AFM interaction between the ICs conflicts with uniform arrangement of the hedgehog state, the strong uniaxial anisotropy as well as the strong N.N.N. AFM interaction inside the IC gives rise to the metastable state within the linear spin-wave theory. It should be noted here that the true ground state is the hedgehog-anti-hedgehog ordered state as shown in Ref.16 and the uniform hedgehog order is the metastable state with the higher energy. In this report, the results for , , and are presented as the representative case of the uniform hedgehog order. Figure 3 shows for (solid line) along the symmetry line illustrated in the inset. Because of the uniaxial anisotropy due to the CEF, the energy dispersion emerges beyond the excitation gap.

Figure 3.

The excitation energy (solid line) and (dashed line) for along the symmetry line in the bcc unit cell illustrated in the inset. The inset shows the unit cell of the bcc lattice of the 1/1 AC in the reciprocal lattice space. (This figure is created by using Adobe Illustrator CS5 Version 15.1.0.).

We also plot (dashed line) for along the same symmetry line for the in Fig. 3. It is remarkable that clear deviation from the solid line emerges along the N-P- line, indicating . Namely, nonreciprocal excitation appears in the uniform hedgehog order in the 1/1 AC. We have calculated the magnon dispersion in the collinear FM order in the 1/1 AC and have confirmed that the nonreciprocal dispersion does not appear (Supplementary information, Fig. S1). Since the lattice structure of the 1/1 AC has the inversion symmetry (see Fig. 1B), the emergence of the nonreciprocal dispersion is ascribed to the alignment of the magnetic moments in the hedgehog state (see Fig. 1A). This point will be discussed in detail in the section of analysis of nonreciprocal excitation below.

Magnetic dynamical structure factor. Next, we calculate the magnetic dynamical structure factor defined by

| 10 |

where is the ground state with the energy and is the Fourier transformation of the “spin” operator defined by . We set . The intensity of inelastic neutron scattering is expressed by the dynamical structure factor

| 11 |

where is the incident wavevector and 38. The results of for along the symmetry line in the bcc unit cell illustrated in the inset of Fig. 3 are shown in Fig. 4A. Notable is that the high intensities appear in the high-energy branches, especially along the -H line and the P--N line. In the upper branches, the relatively high and moderate intensities appear.

Figure 4.

Intensity plots of the dynamical structure factors (A) and (B) along the symmetry line in the unit cell of the bcc lattice illustrated in the inset of Fig. 3. In (B), the color scale is common to that in (A). (This figure is created by using Adobe Illustrator CS5 Version 15.1.0.).

This is in sharp contrast to the case in the collinear FM order in the 1/1 AC where high intensity in and appears continuously from the point in the magnon branch with the lowest excitation energy (Supplementary information, Fig. S3). In Fig. 4, the remarkable intensity appears for along the N-P- line where the nonreciprocal dispersion appears (see Fig. 3).

In the QC, the dynamical structure factor was calculated in Ref.18 where the high intensity appears around the point in the high energy region. The high intensities of around the point, i.e., along the -H line as well as the P--N line shown in Fig. 4A capture this feature. Figure 4B shows the intensity plots of for the same presented in Fig. 4A. By comparing Fig. 4B with Fig. 4A, we see that the nonreciprocity can be detected as the differences in the intensities of and for along the N-P- line. Namely, the nonreciprocal dispersion is remarkable by the intensity differences of the dynamical structure factors in the upper and lower branches.

Analysis of nonreciprocal excitation. To analyze the mechanism of the emergence of the nonreciprocal excitation, let us consider how the excitation from the hedgehog ground state propagates in the 1/1 AC.

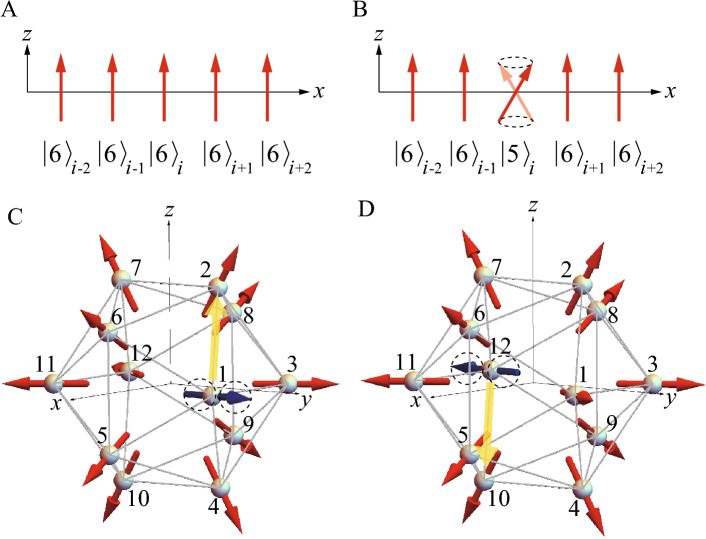

First, for comparison, let us consider the collinear FM ordered state in one dimensional lattice shown in Fig. 5A where the magnetic moment with the total angular momentum is aligned to the z direction and the lattice is formed along the transverse direction, which is set as the x axis. Namely, is realized at each site, which is denoted as , i.e., hereafter. Then, let us consider the excited state created at the ith site, i.e., illustrated in Fig. 5B. This excited state describes the precession around the ordered moment direction, i.e., z axis, which propagates to neighboring sites via the exchange interaction . Namely, the excited state at the ith site propagates to the jth site as

| 12 |

Here, the relation of and and and are used. Hence, for the right neighbor site , the excitation is expressed as the plane wave where a is the lattice constant. For the left neighbor site , the excitation is expressed as the plane wave . The superposition of these yields the excitation energy of the magnon

| 13 |

Since the right moving wave and left moving wave both have the same matrix element as Eq. (12), the excitation has the reciprocal energy with respect to the transverse wavevector to the ordered moment direction, i.e., . It is noted that we have confirmed that the reciprocal magnon dispersion appears in the collinear FM order in the 1/1 AC (Supplementary information, Fig. S2).

Figure 5.

(A) The collinear FM order in the x chain. Each magnetic moment is aligned along the z direction with . (B) The excited state with shows precession at the ith site. (C) The excited state with showing precession of the magnetic moment at the 1st site (blue arrow) on the IC. The propagation of the precession to the 2nd site is illustrated by the yellow arrow. (D) The excited state with showing precession of the magnetic moment at the 12nd site (blue arrow) on the IC. The propagation of the precession to the 10th site is illustrated by the yellow arrow. (This figure is created by using Adobe Illustrator CS5 Version 15.1.0.).

Next, let us consider the excitation from the uniform hedgehog ordered state in the 1/1 AC composed of the regular IC. Suppose that among 12 vertices of the regular IC with the states, an excited state is created at a single site, e.g., the ith site. This excited state can propagate to the neighboring sites via the interaction . Since the state is defined at each site with the local coordinate, hereafter we denote the state at the ith site as . The neighboring state is exchanged as

| 14 |

where is the rotation matrix at the ith site defined in Eq. (20) (see Section “Methods”). Note that as expressed by the component in the right hand side (r.h.s.) of Eq. (14), also contributes to the exchange of and because of the non-collinear alignment of the magnetic moments. The excitation energy is obtained by diagonalizing the matrix describing the propagation of among the states on all the th sites

| 15 |

where i and j denote the Tb sites inside the primitive unit cell of the bcc lattice.

Let us focus on the excited state at the st site illustrated as the precession of the blue arrow in Fig. 5C. This state propagates to the neighboring nd site (see the yellow arrow in Fig. 5C), which is expressed by the matrix element

| 16 |

Here, and are used. On the other hand, the matrix element between the spatially inverted sites and (see the yellow arrow in Fig. 5D) is calculated by Eq. (14) as

| 17 |

Here, and are used. The sign in the term in Eqs. (16) and (17) are opposite, which signals the nonreciprocal excitation. This can be understood by taking the superposition of Eq. (16) and its spatially inverted term Eq. (17) as done in Eq. (13)

| 18 |

The term is even function in terms of , while the term is odd function giving rise to the nonreciprocal contribution. Namely, the sign change occurs when is replaced with in the term, which is in sharp contrast to the collinear FM case in Eq. (13). The term also emerges for the other N.N. sites of , and 6 to the st site and their spatially inverted sites except for the rd site (Supplementary information, Section IV).

By diagonalizing in Eq. (15), the excitation energy is obtained. Figure 6A shows the lowest excitation energy in the h-k plane at for . The result shows indicating that the reciprocal excitation appears in the - plane at . This explains the result shown in Fig. 3 where holds along the -H-N line and the -N line. We have also calculated in the k-l plane at and in the l-h plane at . The result is the same as Fig. 6A with h and k being replaced with k and l respectively in the former case and also with h and k being replaced with l and h respectively in the latter case. These results show that and .

Figure 6.

(A) for in the h-k plane. (B) for in the h-l plane. The color scale is the same as that in (A). (C) for along the symmetry line shown in the inset. (This figure is created by using Adobe Illustrator CS5 Version 15.1.0.).

Next, we plot in the h-l plane for in Fig. 6B. The result shows that , namely, nonreciprocal excitation appears, which is most prominent at . This indicates that the point P and P’ in the reciprocal lattice space (see inset in Fig. 6C) are not equivalent. This explains the result shown in Fig. 3 where the nonreciprocal excitation appears along the N-P- line.

We show for for along the symmetry line displayed in the inset of Fig. 6C. We note that (blue dashed line) at the P point in Fig. 6C is equivalent to the energy at P’ in Fig. 6B. As discussed in Fig. 6B, the nonreciprocal excitation is remarkable along the N-P- line not only for the first excited state, i.e., , but also for as shown in Fig. 6C. These behaviors are consistent with the nonreciprocal feature emerging prominently along the N-P- line in Fig. 3. It is noted that to demonstrate the emergence of the analytic form of the sin function [see Eq. (18)], here we discuss the energy dispersion for the N.N. interaction in Fig. 6C. Since the energy dispersion is plotted in Fig. 3 after subtraction of the ground state energy [see the denominator in r.h.s. of Eq. (10)] for not only the N.N. interaction but also the N.N.N. interaction and uniaxial anisotropy, the energy dispersions in Figs. 3 and 6C are different. However, the nonreciprocal dispersions appear remarkably along the N-P- line in both cases.

The origin of the nonreciprocity can be understood as follows: When the magnetic moment at each Tb site located at the position is spatially inverted by operating with each moment direction being kept (see Fig. 1A), the hedgehog state on the IC is transformed to the anti-hedgehog state. The anti-hedgehog state is defined as the state where the magnetic moment directions are all inverted from those shown in Fig. 1A. The same is applied to the 1/1 AC (see Fig. 1B). Since the magnetic state changes by the space inversion, the inversion symmetry is broken by the hedgehog ordering. Hence, the nonreciprocal dispersion is considered to appear in the excitation from the uniform hedgehog order in the 1/1 AC.

As for the uniform hedgehog order in the QC, the nonreciprocal excitation was reported in Ref.18. Since the infinite limit of the unit cell size of a series of ACs (1/1, 2/1, 3/2, ACs) corresponds to the QC, the infinite folding of the energy dispersion of magnon is expected to occur in the QC. This tendency was indeed confirmed by theoretical calculations in one-dimensional system39 and two-dimensional system40. This is considered to be reflected in the fine structures of the intensities in the dynamical structure factor for the wide - plane in the icosahedral QC as if they are continuum shown in Ref.18 where the recursive structure, i.e., the self-similar structure, appears in the intensities. These results suggest that the hedgehog ordering which breaks the spatial inversion symmetry is the origin of the nonreciprocity in the QC18.

Summary and discussion

We have clarified the dynamical as well as static magnetic structure in the uniform hedgehog order in the 1/1 AC. We have shown that the static structure factor of magnetism in the 1/1 AC is generally expressed as the convolution form where is the lattice structure factor and is the magnetic structure factor of the IC. We have revealed the static structure factor in the uniform hedgehog order by deriving the analytic forms of and as well as by calculating them numerically.

We have discovered that the nonreciprocal dispersion of the excitation energy appears prominently along the N-P- line in the reciprocal lattice space. The dynamical structure factor of the magnetic excitation in the hedgehog state exhibits the high intensities in the high-energy branches along the -H line and the P--N line. The nonreciprocity is remarkable in the high-energy branches for along the N-P- line. The nonreciprocity is clarified to be ascribed to inversion symmetry breaking by the hedgehog ordering whose microscopic source is the strong uniaxial anisotropy D as well as the strong N.N.N. AFM interaction inside the IC. In the ferrimagnetic order in the 1/1 AC, the reciprocal dispersion of the magnetic excitation appears19. Since the spatial inversion symmetry is not broken by the ferrimagnetic order in the 1/1 AC, the above statement is consistent with this case. As for the ferrimagnetic order in the QC discussed in Ref.19, spatial inversion symmetry is not broken. The intensities of the dynamical structure factors and are almost the same but there exist slight differences in the intensities at some points19 [see and in Fig. S5 in Supplementary Information]. The clarification of this origin is left for future study.

In the hedgehog order in the QC, the nonreciprocal excitation in the hedgehog state appears in the vast extent of the - plane where the dynamical structure factor exhibits with considerable intensities18. It is noted that we have confirmed on this point for , i.e., . Namely, exhibits considerable intensities (Supplementary Information, Fig. S6B). In the 1/1 AC, the dynamical structure factor shows remarkable difference between the intensities of and for along the N-P- line where the nonreciprocal dispersion appears.

These results indicate that the emergence of considerable intensity peaks in with different values between and in the wide - plane is attributed to the QC lattice structure.

The present study has pointed out that the inversion symmetry breaking by the uniform hedgehog ordering causes the nonreciprocity . There exists a series of the ACs such as 1/1 AC, 2/1 AC, 3/2 AC, , where the limit in the ACs corresponds to the QC with being the Fibonacci number. Hence, as n increases, the size of the unit cell in the AC expands, where the nonreciprocal dispersion of the excitation energy giving rise to is considered to appear when the uniform hedgehog ordering occurs because of the inversion symmetry breaking. Then, in the limit corresponding to the infinite limit of the unit-cell size of the AC, the nonreciprocity is considered to appear in the uniform hedgehog order in the QC. Hence, the symmetry argument clarified in this study is useful for understanding the nonreciprocal magnetic excitation emerging in the QC.

Thus far, the dynamical structure factor of the icosahedral QC and AC has not been observed experimentally. Hence, the present study is expected to stimulate future experiments to search for unique magnetic states such as the hedgehog and also to observe the dynamical as well as static structure factor of the magnetism.

Methods

Linear spin-wave theory for hedgehog state

To analyze the dynamical structure factor for the hedgehog state in the 1/1 AC, the linear spin-wave theory is used in this study. Since the hedgehog state is non-collinear magnetic state, it is convenient to introduce the local orthogonal coordinate at the ith Tb site spanned by the unit vectors , and 3) (see Fig. 1C) where is directed to the magnetic easy axis of the hedgehog state, i.e., the 5-fold axis direction of the regular IC16. The relation between the unit vector in the global coordinate , and and is given by

| 19 |

where the direction of is expressed by the polar angles and is the rotation matrix given by42,

| 20 |

Then, the interaction of “spins” between the ith and jth sites described by the first term in Eq. (1) is expressed as

| 21 |

By employing the relation and where and are raising and lowering “spin” operators, respectively, we apply the Holstein-Primakoff transformation37 to H. Namely, “spin” operators are transformed to the boson operators as , and with where is the creation (annihilation) operator of the boson at the ith site. We retain the quadratic terms with respect to and , which are considered to be at least valid for the ground state. Since the hedgehog state has non-collinear magnetic structure, the anomalous terms such as and in addition to the normal terms and appear. The position of the ith site is expressed as where denotes the position of the center of the IC and denotes the position of the mth Tb site on the IC. Hence, by performing the Fourie transformations and with being the wave vector, the spin-wave Hamiltonian is expressed by and . Then, by performing the Bogoliubov transformation, i.e., the para-unitary transformation41, the spin-wave Hamiltonian is diagonalized as

| 22 |

Here, is the energy of the th spin wave and is the creation (annihilation) operator of the boson which is given by the linear combination of the boson operators of and .

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The author thanks H. Harima and T. Ishimasa for valuable discussion. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers JP18K03542, JP19H00648, JP22H0459, JP22H01170, and JP23K17672.

Author contributions

S.W. conceived the study and led the project. Theoretical calculation was performed by S.W. The manuscript was written by S.W.

Data availability

All the data supporting the findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-023-41292-1.

References

- 1.Shechtman D, Blech I, Gratias D, Cahn JW. Metallic phase with long-range orientational order and no translational symmetry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1984;53:1951. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.53.1951. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsai AP, Guo JQ, Abe E, Takakura H, Sato TJ. A stable binary quasicrystal. Nature. 2000;408:537. doi: 10.1038/35046202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takakura H, Gómez CP, Yamamoto A, De Boissieu M, Tsai AP. Atomic structure of the binary icosahedral Yb-Cd quasicrystal. Nat. Mater. 2007;6:58. doi: 10.1038/nmat1799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suzuki S, et al. Magnetism of Tsai-type quasicrystal approximants. Mater. Trans. 2021;62:298–306. doi: 10.2320/matertrans.MT-MB2020014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tamura R, Muro Y, Hiroto T, Nishimoto K, Takabatake T. Long-range magnetic order in the quasicrystalline approximant CdTb. Phys. Rev. B. 2010;82:220201(R). doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.82.220201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mori A, et al. Electrical and magnetic properties of quasicrystal approximants RCd (R: Rare Earth) J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2012;81:024720. doi: 10.1143/JPSJ.81.024720. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Das P, et al. Crystal electric field excitations in the quasicrystal approximant TbCd studied by inelastic neutron scattering. Phys. Rev. B. 2017;95:054408. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.95.054408. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ishikawa A, et al. Antiferromagnetic order is possible in ternary quasicrystal approximants. Phys. Rev. B. 2018;98:220403R. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.98.220403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sato TJ, et al. Whirling spin order in the quasicrystal approximant AuAlTb. Phys. Rev. B. 2019;100:054417. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.100.054417. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hiroto T, et al. Ferromagnetism and re-entrant spin-glass transition in quasicrystal approximants Au-SM-Gd (SM = Si, Ge) J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 2013;25:216004. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/25/42/426004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hiroto T, Tokiwa K, Tamura R. Sign of canted ferromagnetism in the quasicrystal approximants Au-SM-R (SM = Si, Ge and Sn/R = Tb, Dy and Ho) J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 2014;26:216004. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/26/21/216004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ishikawa A, et al. Composition-driven spin glass to ferromagnetic transition in the quasicrystal approximant Au-Al-Gd. Phys. Rev. B. 2016;93:024416. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.93.024416. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hiroto T, et al. Noncoplanar ferrimagnetism and local crystalline-electric-field anisotropy in the quasicrystal approximant AuSiTb. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 2020;32:415802. doi: 10.1088/1361-648X/ab997d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tamura R, et al. Experimental observation of long-range magnetic order in icosahedral quasicrystals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021;143(47):19938. doi: 10.1021/jacs.1c09954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Watanabe S, Kawamoto M. Crystalline electronic field in rare-earth based quasicrystal and approximant: Analysis of quantum critical Au–Al–Yb quasicrystal and approximant. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2021;90:063701. doi: 10.7566/JPSJ.90.063701. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watanabe S. Magnetism and topology in Tb-based icosahedral quasicrystal. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:17679. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-97024-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Watanabe S. Topological magnetic textures and long-range orders in Terbium-based quasicrystal and approximant. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2021;118(43):e2112202118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2112202118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watanabe S. Magnetic dynamics of hedgehog in icosahedral quasicrystal. Sci. Rep. 2022;12:15514. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-19870-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Watanabe S. Magnetic dynamics of ferromagnetic long range order in icosahedral quasicrystal. Sci. Rep. 2022;12:10792. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-14796-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kato Y, Hayami S, Motome Y. Spin excitation spectra in helimagnetic states: Proper-screw, cycloid, vortex-crystal, and hedgehog lattices. Phys. Rev. B. 2021;104:224405. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.104.224405. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eto R, Pohle R, Mochizuki M. Low-energy excitations of skyrmion crystals in a centrosymmetric Kondo-lattice magnet: Decoupled spin-charge excitations and nonreciprocity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2022;129:017201. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.129.017201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tokura Y, Kanazawa N. Magnetic skyrmion materials. Chem. Rev. 2021;121:2857. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iguchi Y, Uemura S, Ueno K, Onose Y. Nonreciprocal magnon propagation in a noncentrosymmetric ferromagnet LiFeO. Phys. Rev. B. 2015;92:184419. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.92.184419. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gitgeatpong G, et al. Nonreciprocal magnons and symmetry-breaking in the noncentrosymmetric antiferromagnet. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017;119:047201. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.119.047201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tokura Y, Nagaosa N. Nonreciprocal responses from non-centrosymmetric quantum materials. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:3740. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05759-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sato TJ, Matan K. Nonreciprocal magnons in noncentrosymmetric magnets. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2019;88:081007. doi: 10.7566/JPSJ.88.081007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kravchuk, V. P., Röler, U. K., Brink, J. van den & Garst, M., Solitary wave excitations of skyrmion strings in chiral magnets. Phys. Rev. B102, 220408(R) (2020).

- 28.Seki S, et al. Propagation dynamics of spin excitations along skyrmion strings. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:256. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-14095-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ogawa N, et al. Nonreciprocity of spin waves in the conical helix state. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2021;118(8):e2022927118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2022927118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsumoto T, Hayami S. Nonreciprocal magnon excitations by the Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya interaction on the basis of bond magnetic toroidal multipoles. Phys. Rev. B. 2021;104:134420. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.104.134420. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ishibashi M, et al. Spin wave resonance in perpendicularly magnetized synthetic antiferromagnets. Sci. Adv. 2021;6(17):eaaz6931. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaz6931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nikuni T, Shiba H. Quantum fluctuations and magnetic structures of CsCuCl in high magnetic field. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 1993;62:3268. doi: 10.1143/JPSJ.62.3268. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhitomirsky ME, Zaliznyak IA. Static properties of a quasi-one-dimensional antiferromagnet in a magnetic field. Phys. Rev. B. 1996;53:3428. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.53.3428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miyahara S, Furukawa N. Nonreciprocal directional dichroism and toroidalmagnons in helical magnets. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2012;81:023712. doi: 10.1143/JPSJ.81.023712. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matsumoto T, Hayami S. Nonreciprocal magnons due to symmetric anisotropic exchange interaction in honeycomb antiferromagnets. Phys. Rev. B. 2020;101:224419. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.101.224419. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matsumoto M, Hayashida S, Masuda T. Analysis of field-induced nonreciprocal magnon in noncollinear magnet and application to S = 1 triangular antiferromagnet CsFeCl. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2020;89:034710. doi: 10.7566/JPSJ.89.034710. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holstein T, Primakoff H. Field dependence of the intrinsic domain magnetization of a ferromagnet. Phys. Rev. 1940;58:1098. doi: 10.1103/PhysRev.58.1098. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Squires GL. Introduction to the Theory of Thermal Neutron Scattering. 3. Cambridge University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ashraff JA, Stinchcombe RB. Dynamic structure factor for the Fibonacci-chain quasicrystal. Phys. Rev. B. 1989;39:2670. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.39.2670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wessel S, Milat I. Quantum fluctuations and excitations in antiferromagnetic quasicrystals. Phys. Rev. B. 2005;71:104427. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.71.104427. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Colpa JHP. Diagonalization of the quadratic boson Hamiltonian. Physica A. 1978;93:327. doi: 10.1016/0378-4371(78)90160-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Haraldsen JT, Fishman RS. Spin rotation technique for non-collinear magnetic systems: Application to the generalized Villain model. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 2009;21:216001. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/21/21/216001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All the data supporting the findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.