Abstract

Extensive use of phthalic acid esters (PAEs) as plasticizer causes diffusion into the environment, which posed a great threat to mankind. It was reported that Comamonas sp. was a potentially robust aromatic biodegrader. Although the biodegradation of several PAEs by Comamonas sp. was studies, the comprehensive genomic analysis of Comamonas sp. was few reported. In the present study, one promising bacterial strain for biodegrading diethyl phthalate (DEP) was successfully isolated from activated sludge and characterized as Comamonas sp. USTBZA1 based on the 16S rRNA sequence analysis. The results showed that pH 7.5, 30 °C and inoculum volume ratio of 6% were optimal for biodegradation. Initial DEP of 50 mg/L could be completely biodegrade by strain USTBZA1 within 24 h which conformed to the Gompertz model. Based on the Q-TOF LC/MS analysis, monoethyl phthalate (MEP) and phthalic acid (PA) were identified as the metabolic products of DEP biodegradation by USTBZA1. Furthermore, the whole genome of Comamonas sp. USTBZA1 was analyzed to clarify the molecular mechanism for PAEs biodegradation by USTBZA1. There were 3 and 41 genes encoding esterase/arylesterase and hydrolase, respectively, and two genes regions (pht34512 and pht4253) were responsible for the conversion of PA to protocatechuate (PCA), and two genes regions (ligCBAIKJ) were involved in PCA metabolism in USTBZA1. These results substantiated that Comamonas sp. USTBZA1 has potential application in the DEP bioremediation.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13205-023-03736-3.

Keywords: Diethyl phthalate, Phthalic acid esters, Biodegradation, Comamonas sp. USTBZA1, Pathway, Genome analysis

Introduction

PAEs is a kind of synthetic, colorless, odorless and lipophilic compounds, which was frequently used as plasticizers in polyvinyl chloride (PVC) to enhance polymer versatility and malleability (Shaha and Pandit 2020). These compounds are not covalently bound to polymers and therefore are readily released into the environment including sediments, natural waters, plants and aquatic organisms (Huang et al. 2021). DEP, as a critical kind of PAEs, is commonly used in pharmaceutics, medical bags, shampoo, perfumes, toys and food packaging (Radke et al. 2020). Owing to its ubiquity, the enormous and continuous exposure to DEP is associated with impaired fertility, carcinogenesis, increased oxidative damage to sperm cells, harm to human endocrine and reproductive systems, etc. (Hauser et al. 2007; Gopalakrishnan et al. 2020). It was also listed as one of the six priority-controlled PAEs pollutants by China National Environmental Monitoring Center, the European Union and US Environment Protection Agency (Zhao et al. 2021).

At present, some studies had reported the physical and chemical methods for DEP degradation which were limited in application because of high cost and relatively low efficiency (Gao et al. 2013; Wang et al. 2018; He et al. 2019). Microbial degradation is the main pathway of DEP removal in nature. Although several DEP-biodegrading bacteria has been isolated (such as Sphingomonas sp., Pseudomonas sp., etc.), there was still a lack of highly efficient bacteria for DEP biodegradation (Fang et al. 2007; Tao et al. 2019). It is helpful for the bioremediation of PAEs pollution to seek valuable microbial strains capable of mineralizing DEP completely. Comamonas sp. was a potentially robust aromatic biodegrader that could completely biodegrade dimethyl phthalate (DMP) and dibutyl phthalate (DBP) (Ma et al. 2009; Li et al. 2017; Kumar et al. 2017). However, there was no study of DEP biodegradation by Comamonas sp. and a comprehensive genomic understanding of the entire PAEs metabolism in Comamonas sp. was needed to be clarified.

This study was targeted to determine the characteristic and pathway of DEP biodegradation by a newly isolated strain of Comamonas sp. USTBZA1 and analyze the whole-genome shotgun sequence to clarify the mechanism for PAEs biodegradation in Comamonas sp. USTBZA1.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and culture medium

The compounds of PAEs (purity > 98%) including DMP, DEP, DBP, di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP), dioctyl phthalate (DOP), butyl benzyl phthalate (BBP), monomethyl phthalate (MMP), MEP, monobutyl phthalate (MBP), PA and PCA were purchased from Aladdin Chemistry Co. (Shanghai, China) and their standard stock solution was prepared in methanol. All organic solvents used were of HPLC grade while other reagents were of analytical quality. Luria–Bertani medium (LB) and mineral salt medium (MSM) used in this study were prepared following the method described by Zhao et al. (2021).

Enrichment and isolation of active bacteria

Strain USTBZA1 was isolated from activated sludge and its bacterial suspension was prepared following the enrichment methods described by Zhao et al. (2021). Presumptive DEP-biodegrading colonies of different morphtypes were picked and purified by streaking on LB agar plates at least three times. A promising bacterium named USTBZA1 was confirmed and used.

Biodegradation experiments of DEP by strain USTBZA1

The inoculum suspension was prepared following the method described by Zhao et al. (2021). The OD600 was about 2.1 and approximately 1.1 × 109 colony forming unit (CFU)/mL determined by the colony counting method. In this study the single-factor experiments were performed to investigate the effects of environment factors on DEP biodegradation (55 mg/L) by strain USTBZA1 (cultured for 24 h): initial pH (5.5, 6.5, 7.5, 8.5 and 9.5); culture temperature (15, 25, 30, 37 and 40 °C); initial cell concentrations of 1.09 × 107 CFU/mL (1% of volume ratio), 3.27 × 107 CFU/mL (3% of volume ratio), 6.54 × 107 CFU/mL (6% of volume ratio), 9.81 × 107 CFU/mL (9% of volume ratio) and 13.08 × 107 CFU/mL (12% of volume ratio). In addition, the effect of initial DEP concentrations (55, 110, 550 and 1100 mg/L) on DEP biodegradation was also tested. The blank control was set in the same conditions without inoculating strain USTBZA1.

To investigate the biodegradation kinetics, DEP at the initial concentrations of 55 and 110 mg/L was used as the sole carbon source in the biodegradation experiments with sampling at 6 h intervals and noninoculated medium as a control. DEP residues in culture media were analyzed by a Dionex Ultimate 3000 HPLC (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., USA).

Biodegradation of other PAEs

The capability of strain USTBZA1 to biodegrade other PAEs was investigated in 20 mL MSM supplemented with 50 mg/L of PA, PCA, DMP, DEP, DBP, DOP, DEHP and BBP as the sole carbon source, respectively. After culturing at the optimal conditions for 10 days, the bacterial growth (OD600) and residual PAEs were detected in the culture solution.

HPLC analysis of residual PAEs

Residual PAEs was analyzed by HPLC using the procedure described by Zhao (Zhao et al. 2021). An aliquot of 20 μL was injected into the HPLC system equipped with a C18 reverse-phase column (250 × 4.6 mm2, 5 μm particle size, Dikema Technology Co. Ltd., China) and a UV–Vis detector. The mobile phase was aqueous solution of methanol and 0.5% acetic acid (80:20, v/v) and UV wavelength was at 228 nm. The standard curve was built based on the traditional external method to quantify PAEs. All experiments were performed in triplicates for statistical analysis.

Q-TOF LC/MS analysis of biodegradation products

Three milliliters of bacterial suspension were added into 47 mL MSM with 110 mg/mL DEP in a 250 mL flask, which were sampled at 0, 12, 24, 36, 48 and 60 h respectively to analyze the biodegradation products. Two controls were carried out which contained either strain USTBZA1 grown in LB medium or MSM with DEP. Extraction and cleanup procedures were performed as follows. The sample in a flask was extracted twice with equal volume of dichloromethane and all the organic phase was combined and concentrated by a rotary evaporator (65 °C). The residue was suspended in 5 mL methanol and filtrated for LC/MS (The Agilent 6560 Ion Mobility Q-TOF LC/MS system) analysis. An Agilent Eclipse plus C18 column (50 × 3.0 mm2, 1.8 µm particle size) was used at 45 °C, and a diode array detector was set at 228 nm and 254 nm to detect the biodegradation products. The mobile phase solvent consisted of 5 mM ammonium formate aqueous solution (A) and methanol (B) in a flow rate of 0.3 mL/min. The gradient program was started with 95% A for 1 min, decreased to 65% A gradually in 4 min, and further decreased to 5% A gradually in 20 min, and kept for 5 min, then increased to 95% A in 1 min. The MS detection conditions were capillary voltage of 4000 V, fragmentor voltage 380 V, nebulizer gas (N2) pressure of 40 psi, sheath gas flow rate of 12 L/min and sheath gas temperature of 360 °C. MS analysis was full scan mass spectra (m/z 70–1000) using both positive and negative modes electrospray ionization (ESI+/ESI−).

Identification and draft genome analysis of strain USTBZA1

Identification and the draft genome analysis of strain USTBZA1 were performed as described by Zhao et al. (2021). Strain USTBZA1 was identified based on its morphological characteristics and analysis of 16S rRNA gene sequence. The 16S rRNA gene sequence (GenBank accession number: MW828590) was aligned with Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) in NCBI and its neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree was constructed with the software MEGA 7.0. The sequence read archive (SRA) number of genome sequences was SRR16573717 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/). To define the phylogenetic relationship, the genome sequence of available strains belonging to the same genus in EzBioCloud data base were downloaded from NCBI. The whole-genome average nucleotide identity (ANI) values were obtained from pairwise comparison online (EzBioCloud database) using the Orthologous Average Nucleotide Identity Tool (OAT) to determine whether it is possible to be a new strain (ANI < 95%).

Genome sequencing, assembly and annotation

The genome DNA was extracted using the bacterial DNA Extraction Kit (TIANGEN, China) for electrophoresis detection. The library was constructed with qualified samples. Using the NEB Library Building Kit compatible with Illumina, the second generation genome library of bacterial DNA samples was completed and a small fragment library with a size of 350 bp was constructed. Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer was used to detect the fragment distribution, and qPCR was used to determine the library concentration. After the detection was qualified, the library was double-ended sequenced with Illumina NovaSeq.

Prior to genome assembly, the qualities of the sequencing reads were optimized by fastp software v0.23.2. Through quality control, the theoretical coverage of bacteria clean data was more than 100×, and the quantity and quality met the analysis requirement. For genome assembly, a total of 10 Mb Nanopore long reads with an N50 length of 319 kb were produced. Spades software (combined with its development process) was used for hybrid assembly, while Pilon software v1.5 was used to correct the assembly results. The online NMPDR-rust server was used to forecast the gene and CDSs (coding sequences). Gene annotation was mainly based on the protein sequence alignment in database of Nonredundant Protein Database (NR), Swiss-Prot, Pfam, EggNOG, orthologous groups (COG), GO (gene ontology) and KEGG (Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes) to obtain their functional information (Liu et al. 2022). The genome circle map of strain USTBZA1 was drawn with CGView software to show variation in the genome’s structure (Stothard and Wishart 2005).

Based on the functional annotation of genome sequence, the protein sequence of esterases/hydrolases were compared with reported enzymes for PAEs hydrolysis (Online Resource S1, Table S1) using pairwise sequence alignment by BLAST in NCBI. The genes (pht and oph, lig and tph, etc.) for PA and PCA biodegradation were searched and aligned based on the nucleotide blast in NCBI.

Statistics analyses

All the statistical analysis was performed by using statistical analysis tools SPSS 28.0 using one-way ANOVA (analysis of variance). The data were evaluated in 95% significance interval (p < 0.05 was considered as the threshold for statistical significance). The degradation ratio of DEP was calculated following the method described by Zhao et al. (2021).

Results

Isolation and identification of strain USTBZA1

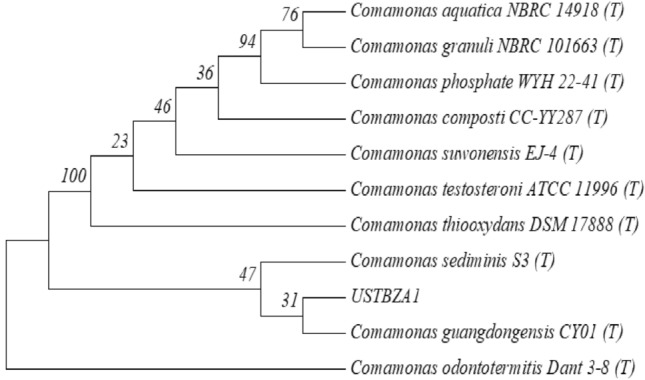

Strain USTBZA1 capable of utilizing DEP as the sole carbon and energy source was isolated from activated sludge. Its colony was milky, round, smooth and glossy surface on an LB agar plate. The morphological examination under a light microscope revealed that cells appeared singly or in pairs, short rods, about (0.5–1.0) × (1.0–4.0) μm in size, Gram-negative without spores (Online Resource S1, Fig. S1). The 16S rRNA gene sequence (1437 bp) of strain USTBZA1 had the closest phylogenetic relationship with Comamonas guangdongensis CY01T with 98.0% of sequence similarity (Fig. 1). Based on the morphological characteristics and 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis, USTBZA1 was identified as a Comamonas sp. strain. The comparison of genome nucleotide sequence showed that strain USTBZA1 shared the highest identity (ANI = 96.32%) to C. thiooxydans DSM 17888 T (there was no genome data available for C. guangdongensis CY01T). Therefore, strain USTBZA1 was probably not a novel specie within Comamonas genus for the ANI > 95%.

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic tree derived from 16S rRNA gene sequences of USTBZA1 and related species by the neighbor-joining approach. The numbers at the branch nodes are bootstrap values on 1000 re-samplings

Effects of environmental factors on DEP biodegradation by strain USTBZA1

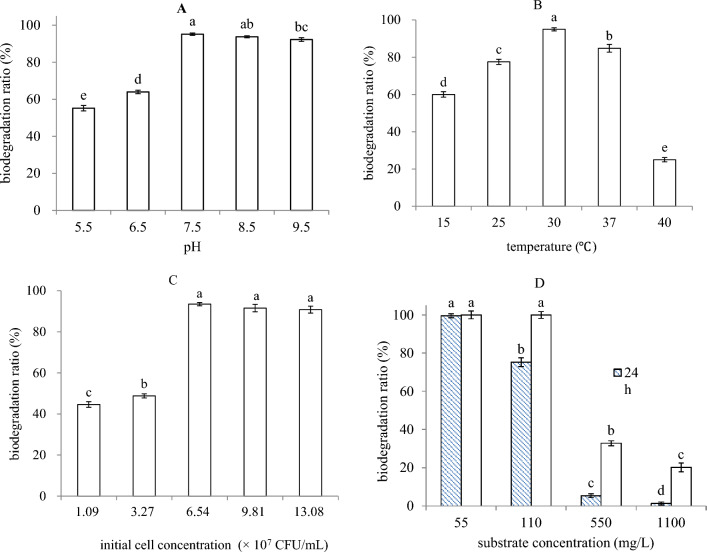

Figure 2A–C showed the effects of environmental factors on the biodegradation ratios of DEP (55 mg/L) by strain USTBZA1 after 24 h. The ratios of DEP biodegradation were all higher than 92% when pH values were at 7.5, 8.5 and 9.5, which were not significantly different. But it was declined to 64% and 55% at pH 6.5 and pH 5.5, respectively (Fig. 2A). The results implied that neutral and alkaline conditions were more suitable for strain USTBZA1 to biodegrade DEP. The biodegradation efficiency of DEP was significantly affected by culture temperatures. It was about 95% at 30 °C, but declined to 85%, 78%, 60% and 25% with the temperature at 37, 25, 40 and 15 °C, respectively (Fig. 2B). It indicated that mesophilic temperature was suitable for strain USTBZA1 to biodegrade DEP. When the initial cell concentration of USTBZA1 was higher than 6.54 × 107 CFU/mL (inoculum size of 6%), the biodegradation ratios were all above 91% which were not significantly different. However, it was below 50% when the initial cell concentration was less than 6.54 × 107 CFU/mL (Fig. 2C). Therefore, the optimal conditions for DEP biodegradation by strain USTBZA1 were at initial cell concentration of 6.54 × 107 CFU/mL, pH 7.5 and 30 °C. Additionally, within the initial concentration of 55 and 110 mg/L, biodegradation ratios were higher than 66% at 24 h, even up to 100% at 72 h (Fig. 2D). However, they were declined to 32.8% and 20.19% at 72 h when the initial concentrations were 550 and 1100 mg/L, respectively. These results demonstrated that high concentration (> 550 mg/L) inhibited strain USTBZA1 to biodegrade DEP.

Fig. 2.

Effects of pH (A), temperature (B), initial cell concentration (C) and initial DEP concentration on biodegradation of DEP (A–C: 55 mg/L DEP) by Comamonas sp. USTBZA1. Error bars indicate the standard error of three replicates; lowercase letters represent the significant levels (p < 0.05)

The biodegradation of DEP by strain USTBZA1

The dynamic curves of DEP biodegradation were shown in Fig. S2 (Online Resource S1). The removal time of DEP extended from 24 to 54 h as the concentration was increased from 55 to 110 mg/L. The bacterial growth (OD600) gradually increased during the biodegradation process which indicated that strain USTBZA1 could gain carbon source and energy by biodegrading DEP. Gompertz model was usually applied to describe sigmoidal curves (Fan et al. 2004). The DEP biodegradation by USTBZA1 was assumed to fit to the Gompertz model, which had the following form:

| 1 |

where S was the substrate concentration at time t, S0 represented the initial substrate concentration (mg/L); Rm was the maximum substrate rate (mg/(L h)); t0 represented the lag phase time (h). The biodegradation process fitted well to the modified Gompertz model at the tested concentrations (R2 > 0.98). The best-fit kinetic parameters in Table 1 showed that t0 extended from 10.4 h to 15.3 h with the concentration increasing from 55 to 110 mg/L, and the maximum substrate biodegradation rates (Rm) were 5.6 and 3.7 mg/(L h), respectively.

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters of DEP biodegradation using the modified Gompertz model

| Initial concentration (mg/L) | t0* (h) | Rm** (mg/(L h)) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 55 | 10.4 | 5.6 | 0.9881 |

| 110 | 15.3 | 3.7 | 0.9936 |

*t0 represented the lag phase time

**Rm was the maximum substrate rate

Substrate utilization of strain USTBZA1

MSM supplemented with each substrate (50 mg/L) was used to test substrate range (Online Resource S1, Fig. S3). Strain USTBZA1 completely biodegraded DMP, DEP, MMP, MEP, PA and PCA within 1 days, removed 85.3% of DBP in 3 days and 64.6% of BBP in 7 days, but hardly biodegraded DEHP and DOP after 10 days. At the same time, strain USTBZA1 utilized PA or PCA as the sole source of carbon and energy for growth. These findings suggested that USTBZA1 had high efficiency on the biodegradation of PAEs with shorter alkyl chains, but hardly biodegrade PAEs with longer alkyl chains in 10 days. Besides, PA and PCA might be the intermediate products of PAEs biodegradation by strain USTBZA1.

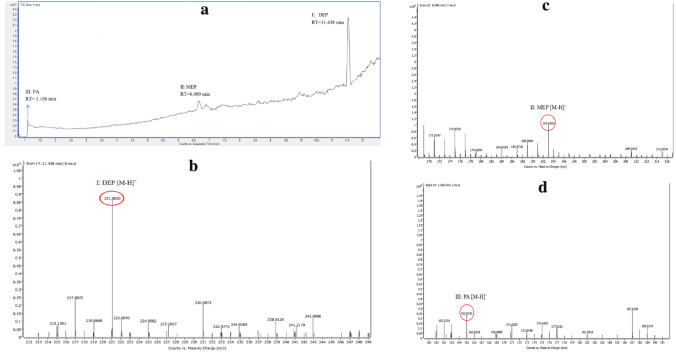

Products of DEP biodegradation analyzed by LC/MS

The biodegradation products of DEP (110 mg/L) by USTBZA1 were analyzed using Q-TOF LC/MS at the UV wavelength of 228 nm and 254 nm. As shown in Fig. 3a, the DEP had a retention time (RT) of 11.438 min, and its fragment ion was at m/z 221.0820 (Fig. 3b). After 36 h biodegradation, two new peaks except DEP appeared in TIC spectrum (Fig. 3a). The MS spectra of the new peak with RT 6.600 min was at m/z 193.0506 (Fig. 3c), which was formed by the loss of one –C2H4 (M = 28) from DEP. Thus, the first biodegradation product was identified as MEP. In addition, the other product peak with RT 1.160 min was at m/z 165.0195, which was formed by the loss of one –C2H4 (M = 28) from MEP. Thus, the second degradation product was identified as PA (Fig. 3d). The characteristic parameters of DEP and its two products were shown in Table S2 (Online Resource S1).

Fig. 3.

The results of LC/MS analysis of DEP biodegradation by Comamonas sp. USTBZA1. A total ion chromatogram of 36 h sample; B–D mass spectrograms of DEP and its products using negative modes electrospray ionization (ESI−)

As the biodegradation proceeded, the peak areas of DEP and the other two products decreased rapidly and disappeared at the end of experiment, further indicating that USTBZA1 could use these compounds as carbon source. During the biodegradation process, the other metabolites such as PCA were not detected probably owing to their immediate degradation by USTBZA1. In the control group (sterile MSM without USTBZA1 or LB with USTBZA1), DEP changed little and no metabolites were detected throughout the experiment period. These results indicated that USTBZA1 biodegraded DEP completely by pathway of MEP and PA (Fig. 4.)

Fig. 4.

The predicted pathway of DEP biodegradation by USTBZA1

Genomic analysis of strain USTBZA1

Based on the Illumina Hiseq platform, the draft genome was sequenced using the method of paired-end reads. With an average coverage depth exceeding 100 × , the quantity and quality met the analysis requirements and sequencing statistics (Online Resource S1, Table S3). Strain USTBZA1 had a total length of 5,684,228 bp with an average GC content of 60.76%. The genome contained 5248 predicted CDSs with an average size of 910 bp, giving a coding intensity of 92%. It revealed 79 tRNA genes and 5 rRNA genes (Online Resource S1, Table S4). Of the 5248 CDSs, 3200 were assigned to 20 different categories of clusters in COG. These results clearly suggested the efficient lipid, carbohydrate and amino acid transport and metabolism for energy in strain USTBZA1 (Online Resource S1, Fig. S4). Average nucleotide identity (ANI) analysis showed that Comamonas sp. USTBZA1 was phylogenetically related to C. testosteroni NCTC 10698T (94.49%) and C. thiooxydans DSM 17888T (96.32%).

KEGG annotation

There were 2470 genes assigned to 247 pathways in KEGG, and 882 (35.71%), 267 (10.81%) and 219 (8.87%) genes were annotated to pathways of global and over view maps of metabolism, amino acid metabolism and carbohydrate metabolism, respectively. Especially, 151 genes were involved in 19 pathways of xenobiotics biodegradation and metabolism (Online Resource S1, Fig. S5 and Table S5). For example, 87, 16, 20 and 21 genes were annotated to benzoate degradation, dioxin degradation, aminobenzoate degradation and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon degradation, which provided a molecular basis for organic pollutants biodegradation in strain USTBZA1.

Genes annotated to esterase

In the present study, strain USTBZA1 could completely biodegrade DMP, DEP, MMP, MEP, PA and PCA. It was reported that PAEs were hydrolyzed to the corresponding monoesters and PA by esterases (Engelhardt and Wallnfer 1978). There were 3 and 41 genes encoding esterase/arylesterase and hydrolase/alpha/beta hydrolase, respectively, based on NR analysis (Online Resource S1, Table S6). However, all of them showed low amino acid identity (< 45%) to those reported enzymes (Blast results above 20% were listed in Online Resource S2) for PAEs hydrolysis (Ren et al. 2018). The annotated hydrolases with identity above 20% were listed in supplementary material 3. Further experiments for functional validation of these genes would be beneficial for understanding the mechanism of PAEs hydrolysis in genus Comamonas.

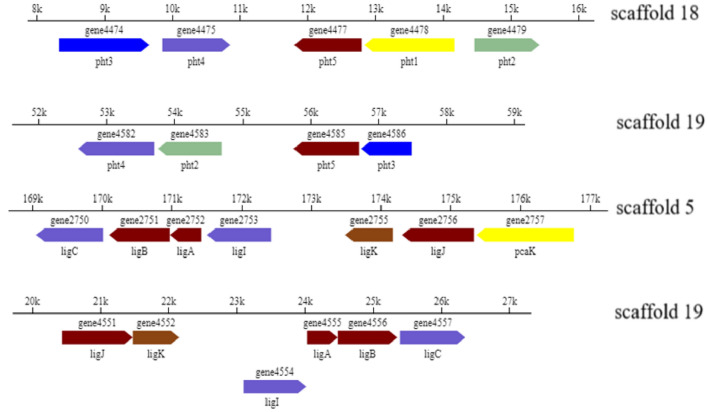

Genes associated with PA biodegradation

In Gram-negative bacteria, PA could be transformed to PCA by PA catabolic gene cluster (pht) and further metabolized by lig genes through 4, 5-cleavage pathway (Providenti et al. 2001; Ni et al. 2013). Based on the Swiss-Prot annotation of the genome sequence, four gene regions located in scaffold 5, scaffold 18 and scaffold 19 were annotated to pht and lig genes (listed in Online Resource S1, Table S7) and their organizations were shown in Fig. 5. Two pht gene regions were located in scaffold 18 (pht34512) and scaffold 19 (pht4253) which were different in length and arrangement. The genes of pht1, pht2, pht3, pht4 and pht5 encoded PA transporter and a series of enzymes which were involved in PA biodegradation. Two lig gene regions were located in scaffold 5 (ligCBAIKJ) and scaffold 19 (ligJKIABC) which were almost the same in length and arrangement. The genes of ligA, ligB, ligC, ligI, ligJ and ligK encoded enzymes for PCA biodegradation.

Fig. 5.

Gene organizations of pht and lig genes in Comamonas sp. USTBZA1

Predicted biodegradation pathway of PA

All the genes (pht and lig) and their encoded enzymes for PA and PCA biodegradation were found in the pathways of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon degradation and benzoate degradation (Online Resource S1, Fig. S6 and Fig. S7, the part in red circle). Based on the KEGG annotation, the mechanism of PA biodegradation in USTBZA1 could be described as shown in Fig. 6. PA was first transformed into phthalate-4, 5-cis-dihydrodiol which was mediated by phthalate 4, 5-dioxygenase [EC: 1.14.12.7] and phthalate 4, 5-dioxygenase reductase component [EC: 1.18.1.-] encoded by pht3 and pht2 respectively, and then was converted into 4, 5-dihydroxyphthalate mediated by phthalate 4, 5-cis-dihydrodiol dehydrogenase [EC: 1.3.1.64] encode by pht4, and then was transformed into the key intermediate PCA (3,4-dihydroxybenzoate) mediated by 4, 5-dihydroxyphthalate decarboxylase [EC: 4.1.1.55] encoded by pht5. The ring-cleavage of PCA was mediated by protocatechuate 4, 5-dioxygenase [EC: 1.13.11.8] (an extradiol ring-cleavage dioxygenases, encoded by ligA and ligB) which generated 4-carboxy-2-hydroxymuconate semialdehyde and then was isomerizated into 2-hydroxy-2-hydropyrone-4, 6-dicarboxylate. The product was converted into 4-oxalomesaconate catalyzed by 2-pyrone-4, 6-dicarboxylate lactonase [EC: 3.1.1.57] encoded by ligI and then was isomerizated into 4-carboxy-2-hydroxy-cis, cis-muconate, and subsequently was transformed into 4-carboxy-4-hydroxy-2-oxoadipate by 4-oxalmesaconate hydratase [EC: 4.2.1.83] encoded by ligJ. 4-carboxy-4-hydroxy-2-oxoadipate was decomposed into oxaloacetate and pyruvate mediated by 4-hydroxy-4-methyl-2-oxoglutarate aldolase [EC: 4.1.3.17] encoded by ligK, which entered into citrate cycle (TCA cycle) and was biodegraded completely.

Fig. 6.

Predicted biodegradation pathway of PA in Comamonas sp. USTBZA1 based on the KEGG annotation

Discussion

Comamonas (formerly Pseudomonas) species were metabolically diverse. They dwelled in a wide range of habitats such as activated sludge (Gumaelius et al. 2001), soils, fresh and marine sediments (Shinomiya et al. 1997), which were genetically dynamic and equipped for adaptation to changing environments and xenobiotic compounds such as hydroxybenzoate (Michalover et al. 1973), p-toluate (Locher et al. 1991), m-nitrobenzoate (Nadeau and Spain 1995), naphthalene and anthracene (Goyal & Zylstra 1996), phthalates (Wang et al. 1995; Kumar et al. 2017; Li et al. 2017), chloronitrobenzenes (Katsivela et al. 1999; Wu et al. 2005), etc. In this study, Comamonas sp. USTBZA1 could completely biodegrade 110 mg/L DEP within 54 h, which was much higher than that of some reported DEP-biodegrading bacteria, such as Mycobacterium sp. YC-RL4 (removed 50 mg/L DEP in 5 days), Rhodococcus sp. L4 (biodegraded 100 mg/L DEP in 6 days), Gordonia alkanivorans YC-RL2, Sphigomonas sp. DK4 and Corynebacterium sp. O18 (biodegraded 100 mg/L DEP in 7 days) (Chang et al. 2004; Lu et al. 2009; Nahurira et al. 2017; Ren et al. 2016). Therefore, Comamonas sp. UATBZA1 was a competent candidate for the bioremediation of DEP contaminated environment.

Environmental factors influenced the biodegradation process. The high biodegrading ratio of strain USTBZA1 under neutral and alkaline conditions would be beneficial to remove DEP in such environment, which was similar to the DEP biodegradation by Rhodococcus sp. L4 (Lu et al. 2009). The biodegradation ratio could be further improved by increasing inoculum size which was consistent with the DMP biodegradation by Comamonas testosterone DB-7 (Li et al. 2017). The best biodegradation efficiency was achieved at inoculum size of 6%, pH 7.5 and 30 °C.

We noticed that the enhanced biodegradation occurred after a prolonged culture (a lag phase) which might be since that bacterial growth started slowly and required an acclimation period before accelerated biodegradation. The DEP biodegradation process by USTBZA1 fitted well with the modified Gompertz model at the tested concentrations (R2 > 0.98), which was consistent with the DMP biodegradation by Comamonas testosterone DB-7 and the DEP biodegradation by Sphingomonas sp. DEP-AD1 (Fang et al. 2007; Li et al. 2017).

PAEs were firstly converted to PA by hydrolase or esterases and then PA was metabolized by ring-cleavage enzymes. Reported PAEs hydrolase, which contributed to ester bond hydrolyzation, included mono-2-ethylhexyl phthalate hydrolase from Gordonia sp. P8219 (Nishioka et al. 2006), ester hydrolase PatE from Rhodococcus jostii RHA1 (Hara et al. 2010), dialkyl PE hydrolase (DphA and DphB) from uncultured bacteria (Jiao et al. 2013), dialkyl PE hydrolase from Acinetobacter sp. M673 (Wu et al. 2013), esterase EstS1 from Sulfobacillus acidophilus DSM10332 (Zhang et al. 2014) and CarEW from Bacillus sp. K91 (Ding et al. 2015), etc. However, all these encoded esterase/hydrolase have no more than 50% sequence identity with reported PAEs hydrolase (Table S1). For example, gene3467, gene2747 and gene3808 showed 41.096%, 39.228% and 33.684% identity with dialkyl PAEs hydrolase (DphB, AGY55960.1) from an uncultured bacterium with 97%, 97% and 67% coverage, respectively; gene3658 and gene4816 showed 22.569% and 28.322% identity with mono-ethylhexyl phthalate hydrolase (BAU22081.1) from Rhodococcus sp. EG-5 with 95% and 90% coverage, respectively. Therefore, the properties and functions of enzymes encoded by these potential functional genes deserved further research.

Specific genes involved in PA catabolism have been characterized in some Gram-negative bacteria (Nomura et al. 1992; Chang and Zylstra 1998). In Comamonas sp. USTBZA1, the genes pht4253 in scaffold 19 were organized in the same direction and with an insert of MarR family transcriptional regulator (gene4476) between pht4 and pht5; while the genes pht34512 in scaffold 18 arranged in a different order and with an insert of tripartite tricarboxylate transporter substrate-binding protein (gene4584) between pht2 and pht5. This is different from the arrangement of reported pht genes (Shen et al. 2019) (Online Resource S1, Fig. S8). The results of protein sequence alignment revealed that all the products (enzymes) of pht genes (pht2, pht3, pht4, pht5) in scaffold18 exhibited almost 100% identity (100% coverage) with the enzymes encoded by the oph gene cluster responsible for PA biodegradation (ophA1, ophA2, ophB, ophC, respectively) from Comamonas sp. strain E6 (NBRC 107749) (Shimodaira et al. 2015). And the PA transporter encoded by gene4478 (pht1) showed 100% identity with the major facilitator transporter (KGH01290.1) from Comamonas thiooxydans JC8. However, the pht genes in scaffold 19 exhibited 55.8%-72.8% identity (93%-100% coverage) with the enzymes encoded by ophA1A2BC from Comamonas sp. strain E6 (Online Resource S3). In addition, the tph genes responsible for terephthalate biodegradation were found on the upstream of the pht genes in scaffold 18, which was different from Comamonas sp. Strain E6 with tph genes located downstream of the pht genes (Online Resource S1, Fig. S9).

Hara et al. (2000) reported that on the physical map of lig genes encoding the PCA meta-pathway enzymes of Sphingomonas paucimobilis SYK-6, homologous lig and pmd genes were shaded identically. In Comamonas sp. USTBZA1, all the products of lig genes (ligA, ligB, ligC, ligI, ligJ and ligK) in scaffold 5 exhibited > 98.6% identity (100% coverage) with the enzymes (PmdA, PmdB, PmdC, PmdD, PmdE and PmdF, respectively) from Comamonas testosteroni BR6020 (Providenti et al. 2001). Furthermore, the 4-hydroxybenzoate transporter encoded by gene2757 (pcaK) showed 98.9% identity with the putative transporter (PmdK) from C. testosteroni BR6020. While the lig genes in scaffold 19 exhibited 79.6–91.6% identity (> 99% coverage) with the Pmd enzymes from C. testosteroni BR6020. Above all, these findings provided a molecular database to investigate related functional genes of Comamonas sp. USTBZA1 for the PAEs biodegradation.

Based on the metabolic pathway annotation in KEGG, all the genes referred to PA biodegradation was found except the gene (galD) which encoded 4-oxalomesaconate tautomerase [EC: 5.3.2.8] catalyzing the isomerization of 4-oxalomesaconate to 4-carboxy-2-hydroxy-cis, cis-muconate. Perhaps, there was other genes or isozymes in USTBZA1 mediated the isomerization. Whole-genome sequencing and analysis revealed the molecular mechanism of PAEs biodegradation which provided genes resources for further research in PAEs biodegradation.

Conclusions

A DEP-biodegrading Comamonas sp. USTBZA1 was acquired from activated sludge. The optimal culture conditions for its biodegradation were 30 °C, pH 7.5 and inoculum volume ratio of 6%. The kinetics for DEP biodegradation with 55 and 110 mg/L by strain USTBZA1 fitted well with the modified Gompertz model. Importantly, the draft genome analysis revealed that 44 genes encoding esterase/arylesterase/hydrolase might be involved in hydrolyzing DEP to PA and functional genes for the whole-metabolic pathway of PA biodegradation were annotated. These findings were helpful to the enrichment of microbe resources for PAEs biodegradation and clarification the molecular mechanisms of PAEs biodegradation in Comamonas sp. strains.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Funding

The work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21677011) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (PRF-MP-20-39).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to this work. We declare that we do not have any commercial or associative interest that represents a conflict of interest in connection with the work submitted.

Ethical approval

The manuscript does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

This paper has not been published before in any form. It is not under consideration by another journal at the same time. That all authors approve of its submission.

Contributor Information

Zhenzhen Zhao, Email: 20230012@wfu.edu.cn.

Yanfeng Liu, Email: wf8529087@sina.com.

Chao Liu, Email: lch1092@126.com.

Qianqian Xu, Email: qianqianxu@ustb.edu.cn.

Meijie Song, Email: meijie_song@126.com.

Hai Yan, Email: haiyan@ustb.edu.cn.

References

- Chang HK, Zylstra GJ. Novel organization of the genes for phthalate degradation from Burkholderia cepacia DBO1. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6529–6537. doi: 10.1128/JB.180.24.6529-6537.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang B, Yang C, Cheng C, Yuan S. Biodegradation of phthalate esters by two bacteria strains. Chemosphere. 2004;55:533–538. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2003.11.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding J, Wang C, Xie Z, Li J, Yang Y, Mu Y, Tang X, Xu B, Zhou J, Huang Z. Properties of a newly identified esterase from Bacillus sp. K91 and its novel function in diisobutyl phthalate degradation. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0119216. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelhardt G, Wallnfer PR. Metabolism of Di- and Mono-n-Butyl Phthalate by Soil Bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1978;35:243–246. doi: 10.1128/aem.35.2.243-246.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y, Wang Y, Qian PY, Gu JD. Optimization of phthalic acid batch biodegradation and the use of modified Richards model for modeling degradation. Int Biodeterior Biodegrad. 2004;53:57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ibiod.2003.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fang H, Liang D, Zhang T. Aerobic degradation of diethyl phthalate by Sphingomonas sp. Bioresour Technol. 2007;98:717–720. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2006.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao B, Wang P, Zhou H, Zhang Z, Wu F, Jin J, Kang M, Sun K. Sorption of phthalic acid esters in two kinds of landfill leachates by the carbonaceous sorbents. Bioresour Technol. 2013;136:295–301. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2013.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopalakrishnan K, Aushev VN, Manservisi F, Falcioni L, Panzacchi S, Belpoggi F, Parada H, Garbowski G, Hibshoosh H, Santella RM, Gammon MD. Gene expression profiles for low-dose exposure to diethyl phthalate in rodents and humans: a translational study with implications for breast carcinogenesis. Sci Rep. 2020;10:7076. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-63904-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyal AK, Zylstra GJ. Molecular cloning of novel genes for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon degradation from Comamonas testosteroni GZ39. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:230–236. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.1.230-236.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gumaelius L, Magnusson G, Pettersson B, Dalhammar G. Comamonas denitrificans sp. nov., an efficient denitrifying bacterium isolated from activated sludge. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2001;51:999–1006. doi: 10.1099/00207713-51-3-999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara H, Masai E, Katayama Y, Fukuda M. The 4-oxalomesaconate hydratase gene, involved in the protocatechuate 4, 5-cleavage pathway, is essential to vanillate and syringate degradation in Sphingomonas paucimobilis SYK-6. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:6950–6957. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.24.6950-6957.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara H, Stewart GR, Mohn WW. Involvement of a novel ABC transporter and monoalkyl phthalate ester hydrolase in phthalate ester catabolism by Rhodococcus jostii RHA1. Appl Environ Microb. 2010;76:1516–1523. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02621-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser R, Meeker JD, Singh NP, Silva MJ, Ryan L, Duty S, Calafat AM. DNA damage in human sperm is related to urinary levels of phthalate monoester and oxidative metabolites. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(3):688–695. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Z, Li Z, Zhang Q, Wei Z, Duo J, Pan X. Simultaneous remediation of As (III) and dibutyl phthalate (DBP) in soil by a manganese–oxidizing bacterium and its mechanisms. Chemosphere. 2019;220:837–844. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.12.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L, Zhu X, Zhou S, Cheng Z, Shi K, Zhang C, Shao H. Phthalic acid esters: natural sources and biological activities. Toxins. 2021;13(7):495. doi: 10.3390/toxins13070495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao Y, Chen X, Wang X, Liao X, Xiao L, Miao A, Wu J, Yang L. Identification and characterization of a cold-active phthalate esters hydrolase by screening a metagenomic library derived from biofilms of a wastewater treatment plant. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e75977. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsivela E, Wray V, Pieper DH, Wittich RM. Initial reactions in the biodegradation of 1-chloro-4-nitrobenzene by a newly isolated bacterium, strain LW1. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:1405–1412. doi: 10.1128/AEM.65.4.1405-1412.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V, Sharma N, Maitra SS. Comparative study on the degradation of dibutyl phthalate by two newly isolated Pseudomonas sp. V21b and Comamonas sp. 51F. Biotechnol Rep. 2017;28:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.btre.2017.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Luo F, Chu D, Xuan H, Dai X. Complete degradation of dimethyl phthalate by a Comamonas testosterone strain. J Basic Microbiol. 2017;57:941–949. doi: 10.1002/jobm.201700296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Xu Q, Zhao Z, Zhang H, Liu X, Yin C, Liu Y, Yan H. Genomic analysis of Sphingopyxis sp. USTB-05 for biodegrading cyanobacterial hepatotoxins. Toxins. 2022;14:333. doi: 10.3390/toxins14050333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locher HH, Malli C, Hooper S, Vorherr T, Leisinger T, Cook AM. Degradation of p-toluic acid (p-toluene-carboxylic acid) and p-toluenesulphonic acid via oxygenation of the methyl sidechain is initiated by the same set of enzymes in Comamonas testosteroni T-2. J Gen Microbiol. 1991;137:2201–2208. doi: 10.1099/00221287-137-9-2201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, Tang F, Wang Y, Zhao JH, Zeng X, Luo QF, Wang L. Biodegradation of dimethyl phthalate, diethyl phthalate and di-n-butyl phthalate by Rhodococcus sp. L4 isolated from activated sludge. J Hazard Mater. 2009;168:938–943. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.02.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma YF, Zhang Y, Zhang JY, Chen DW, Zhu YQ, Zheng HJ, Wang SY, Jiang CY, Zhao GP, Liu SJ. The complete genome of Comamonas testosteroni reveals its genetic adaptations to changing environments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:6812–6819. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00933-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalover JL, Ribbons DW, Hughes H. 3-Hydroxybenzoate 4-hydroxylase from Pseudomonas testosteroni. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1973;55:888–896. doi: 10.1016/0006-291X(73)91227-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadeau LJ, Spain JC. Bacterial degradation of m-nitrobenzoic acid. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:840–843. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.2.840-843.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahurira R, Ren L, Song JL, Jia Y, Wang JH, Fan SH, Wang HS, Yan YC. Degradation of Di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate by a novel Gordonia alkanivorans strain YC-RL2. Curr Microbiol. 2017;74:309–319. doi: 10.1007/s00284-016-1159-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni B, Zhang Y, Chen DW, Wang BJ, Liu SJ. Assimilation of aromatic compounds by Comamonas testosteroni: characterization and spreadability of protocatechuate 4, 5-cleavage pathway in bacteria. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;97:6031–6041. doi: 10.1007/s00253-012-4402-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishioka T, Iwata M, Imaoka T, Mutoh M, Egashira Y, Nishiyama T, Shi T, Fujii T. A mono-2-ethylhexyl phthalate hydrolase from a Gordonia sp. that is able to dissimilate di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:2394–2399. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.4.2394-2399.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomura Y, Nakagawa M, Ogawa N, Harashima S, Oshima Y. Genes in PHT plasmid encoding the initial degradation pathway of phthalate in Pseudomonas putida. J Ferment Bioeng. 1992;74:333–334. doi: 10.1016/0922-338X(92)90028-S. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Providenti MA, Mampel J, MacSween S, Cook AM, Wyndham RC. Comamonas testosteroni BR6020 possesses a single genetic locus for extradiol cleavage of protocatechuate. Microbiol. 2001;147:2157–2167. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-8-2157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radke EG, Braun JM, Nachman RM, Cooper GS. Phthalate exposure and neurodevelopment: a systematic review and meta-analysis of human epidemiological evidence. Environ Int. 2020;137:105408. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2019.105408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren L, Jia Y, Ruth N, Qiao C, Wang JH, Zhao BS, Yan YC. Biodegradation of phthalic acid esters by a newly isolated Mycobacterium sp. YC-RL4 and the bioprocess with environmental samples. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2016;23:16609–16619. doi: 10.1007/s11356-016-6829-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren L, Lin Z, Liu HM, Hu HQ. Bacteria-mediated phthalic acid esters degradation and related molecular mechanisms. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2018;102:1085–1096. doi: 10.1007/s00253-017-8687-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaha CM, Pandit RS. Biochemical and molecular changes mediated by plasticizer diethyl phthalate in Chironomus circumdatus (bloodworms) Comp Biochem Physiol c: Pharmacol Toxicol. 2020;228:108650. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2019.108650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen S, Wang XY, Wang HX, Ren H, Lü ZM. Advances in biodegradation of phthalates esters (Article in Chinese) Chin J Biotechnol. 2019;35:2104–2120. doi: 10.13345/j.cjb.190177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimodaira J, Kamimura N, Hosoyama A, Yamazoe A, Fujita N, Masai E. Draft genome sequence of Comamonas sp. strain E6 (NBRC 107749), a degrader of phthalate isomers through the protocatechuate 4, 5-cleavage pathway. Genome Announc. 2015;3:e00643–e715. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00643-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinomiya M, Iwata T, Kasuya K, Doi Y. Cloning of the gene for poly (3-hydroxybutyric acid) depolymerase of Comamonas testosteroni and functional analysis of its substrate-binding domain. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;154:89–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb12628.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stothard P, Wishart DS. Circular genome visualization and exploration using CGView. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(4):537–539. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao Y, Li H, Gu J, Shi H, Han S, Jiao Y, Zhong G, Zhang Q, Akindolie MS, Lin Y, Chen Z, Zhang Y. Metabolism of diethyl phthalate (DEP) and identification of degradation intermediates by Pseudomonas sp. DNE-S1. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2019;173:411–418. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2019.02.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YZ, Zhou Y, Zylstra GJ. Molecular analysis of isophthalate and terephthalate degradation by Comamonas testosteroni YZW-D. Environ Health Perspect. 1995;103:9–12. doi: 10.1289/ehp.95103s49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Chen Q, Liu Y, Ma D, Xin Y, Ma X, Zhang X. In situ synthesis of graphene/WO3 co–decorated TiO2 nanotube array photoelectrodes with enhanced photocatalytic activity and degradation mechanism for dimethyl phthalate. Chem Eng J. 2018;337:322–332. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2017.12.058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu JF, Sun CW, Jiang CY, Liu ZP, Liu SJ. A novel 2-aminophenol 1, 6-dioxygenase involved in the degradation of p-chloronitrobenzene by Comamonas strain CNB-1: purification, properties, genetic cloning and expression in Escherichia coli. Arch Microbiol. 2005;183:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s00203-004-0738-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Liao X, Yu F, Wei Z, Yang L. Cloning of a dibutyl phthalate hydrolase gene from Acinetobacter sp. strain M673 and functional analysis of its expression product in Escherichia coli. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;97:2483–2491. doi: 10.1007/s00253-012-4232-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang XY, Fan X, Qiu XJ, Li CY, Xing S, Zheng YT, Xu JH. Newly identified thermostable esterase from Sulfobacillus acidophilus: properties and performance in phthalate ester degradation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80:6870–6878. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02072-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao ZZ, Liu C, Xu QQ, Ahmad S, Zhang HY, Pang Y, Aikemu A, Liu Y, Yan H. Characterization and genomic analysis of an efficient dibutyl phthalate degrading bacterium Microbacterium sp. USTB-y World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2021;37:212. doi: 10.1007/s11274-021-03181-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.