Highlights

-

•

Resistance to temozolomide is one of the main obstacles to improve the prognosis for glioblastoma patients.

-

•

Methylation status of MGMT promoter in glioblastomas correlates with MGMT expression and resistance.

-

•

CRISPRoff-based targeted hypermethylation of the MGMT promoter represses MGMT expression.

-

•

Reduced MGMT expression enhances susceptibility for temozolomide of resistant glioblastoma cell lines.

-

•

Targeted RNA-guided methylation is a promising tool to overcome resistance and induce cytotoxicity.

Keywords: CRISPR/Cas9 technology, MGMT, Temozolomide, Glioblastoma

Abstract

Glioblastoma is the most common and aggressive primary tumor of the central nervous system with poor outcome. Current gold standard treatment is surgical resection followed by a combination of radio- and chemotherapy. Efficacy of temozolomide (TMZ), the primary chemotherapeutic agent, depends on the DNA methylation status of the O6-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase (MGMT), which has been identified as a prognostic biomarker in glioblastoma patients. Clinical studies revealed that glioblastoma patients with hypermethylated MGMT promoter have a better response to TMZ treatment and a significantly improved overall survival. In this study, we thus used the CRISPRoff genome editing tool to mediate targeted DNA methylation within the MGMT promoter region. The system carrying a CRISPR-deactivated Cas9 (dCas9) fused with a methyltransferase (Dnmt3A/3L) domain downregulated MGMT expression in TMZ-resistant human glioblastoma cell lines through targeted DNA methylation. The reduction of MGMT expression levels reversed TMZ resistance in TMZ-resistant glioblastoma cell lines resulting in TMZ induced dose-dependent cell death rates. In conclusion, we demonstrate targeted RNA-guided methylation of the MGMT promoter as a promising tool to overcome chemoresistance and improve the cytotoxic effect of TMZ in glioblastoma.

Introduction

Glioblastoma is the most common and lethal primary malignancy in the central nervous system. The current standard therapy consists of surgical resection followed by temozolomide (TMZ) chemotherapy, and concomitant ionizing radiotherapy; nevertheless, the prognosis of glioblastoma patients remains poor with a median overall survival of almost 15-18 months [1,2]. The chemoresistance and recurring tumorigenesis are the two main obstacles to improve the prognosis of glioblastoma patients [2].

As one of the first-line chemotherapeutic agents, TMZ is commonly used to treat glioblastoma because of its limited side effects. TMZ is a DNA alkylating agent known to induce cell cycle arrest at G2/M leading to apoptosis. The cytotoxicity of TMZ is mainly mediated by the addition of methyl groups at multiple sites; especially, O6 sites on guanines in genomic DNA [3]. This leads to the insertion of a thymine instead of a cytosine opposite the methylguanine during subsequent DNA replication and can induce cell death [3]. However, these DNA adducts can be rapidly reversed by an intracellular suicide DNA repair enzyme, O6-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase (MGMT), resulting in reduced effectiveness of TMZ in patients [4].

It is well known that MGMT expression is controlled by DNA methylation of the promoter region and hypermethylation results in decreased gene transcription and subsequent MGMT protein expression [5]. The promoter of MGMT gene contains a 760 bp long CpG island (CGI) with 98 CpG sites, whose methylation status has been shown to be a valid biomarker to predict the tumor sensitivity to TMZ in glioblastoma patients [4]. Several clinical studies demonstrated that glioblastoma patients with hypermethylation of the MGMT promoter benefit most from treatment with TMZ and have significantly improved overall survival compared to patients with hypomethylation of the MGMT promoter [6], [7], [8]. Therefore, targeted editing of DNA methylation in the MGMT promoter region may represent a promising approach to enhance the TMZ sensitivity of glioblastomas.

The advances in the CRISPR/Cas9 system have provided novel possibilities for the targeted editing of mammalian genomes. Recently, Weissman and colleagues reported a powerful epigenome-editing tool, called CRISPRoff, which uses a methyltransferase (Dnmt3A/3L) fused to a catalytically inactivate Cas9 (dCas9) to establish targeted DNA methylation and repression of gene expression [9]. Surprisingly for many, most human genes could be specifically silenced by methylation of CpG islands or individual CpG sites. Here, we used CRISPRoff together with several single guide RNAs (gRNA) targeting different sites in the MGMT promoter region and co-transfected known TMZ-resistant glioblastoma cell lines. These epigenetically modified cell lines showed a significantly increased sensitivity to TMZ.

Material and methods

Antibodies and reagents

The primary monoclonal antibodies against MGMT (MA5-13506) and beta actin (A5441) were from Thermo Fisher (Waltham, MA, USA) and Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA), respectively. The secondary HRP conjugated anti-mouse antibody (P0447) was from Dako (Santa Clara, CA, USA). Propidium iodide (PI) (P1304MP) was obtained from Thermo Fisher (Waltham, MA, USA). Proteinase K (3719.2), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (A994.2), skim milk powder (T145.3), and Tween-20 (9127.1) were purchased from Roth (Karlsruhe, BW, DE). Temozolomide was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA), dissolved in DMSO at a concentration of 200 mM and stored in aliquots at -20°C.

Cell lines and cell culture

The glioblastoma cell lines T98G and LN18 were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) Glutamax (31966-021, Gibco) supplemented with 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Sigma) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco). The glioblastoma cell line U138MG was purchased from the German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures GmbH (DSMZ, Braunschweig, Germany) and cultured in Ham's F-10 (11550-043, Gibco) supplemented with 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Sigma) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco). All cell lines were cultured in a humidified incubator containing 5% CO2 at 37°C. Cells were detached using 1% Trypsin EDTA (Gibco) for 5-10 min at 37°C.

Plasmid construction and generation of stably transfected glioblastoma cell lines

The CRISPRoff plasmid (#167981) and gRNA cloning plasmid (#51133) were purchased from Addgene (Watertown, MA, USA). Three gRNAs targeting the MGMT gene promoter CGI region were selected from the UCSC genome browser (https://genome.ucsc.edu/) using the integrated CRISPOR tool (http://crispor.tefor.net). Predicted specificities (off-target effects) and predicted efficiencies of the selected gRNAs were calculated through the tool CRISPOR included in the UCSC genome browser. All gRNA sequences are listed in the Supplementary Table S1. The gRNAs and their respective reverse complements were annealed and cloned into the BsaI site of the gRNA cloning plasmid downstream of the hU6 promoter. All resulting gRNA plasmids were verified by Sanger sequencing.

To generate gRNA stably expressing glioblastoma cell lines, 1.5 × 106 cells from each T98G and LN18 were seeded on 10 cm tissue culture dishes. After reaching a cell density of 80 %, cells were co-transfected with the CRISPRoff plasmid and one of each of the gRNA or the empty gRNA plasmid (at a ratio of 10:1) using Roti-Fect PLUS (Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany) according to manufacturer's protocol. After 24 h, 1µg/ml puromycin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) was added to the transfected cells for selection of single colonies. Single puromycin-resistant colonies were picked after approximately 3-4 weeks of cultivation and transferred into single wells of 24 well plates. When picked colonies were confluent in 24-well plates (approximately 5–7 days), colonies were splitted into two separate 12 well plates. One 12 well plate was used for further expansion and the other for analysis of MGMT expression by Western blot.

Protein extraction, quantification and Western blot analysis

Total protein extracts from cultured cells were prepared in 1x RIPA lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.5 % Triton-X 100) supplemented with Halt Protease Inhibitor-Cocktail (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) and 0.5 µl/ml Benzonase (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) on ice for 30 min. The protein concentrations were determined using Bicinchoninic Acid (BCA) Protein Assay (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA). For electrophoresis, 40 µg protein aliquots were heat denatured by 5 min boiling in Laemmli loading buffer (200 mM Tris-HCl pH 6.8, 6 % 2-mercaptoethanol, 33 % glycerol, 8 % SDS, 0.2% bromophenol blue), separated by 10 % SDS-PAGE and transferred to 0.45 µm nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham, Braunschweig, Germany). The membranes were blocked with 5 % skim milk dissolved in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.1 % Tween 20 (PBST) for 1 h at room temperature and incubated with anti-MGMT (1:1000) or anti-beta-actin (1:10000) antibodies overnight at 4°C. Subsequently, the membranes were washed with PBST and incubated with a secondary, horseradish peroxidase (HRP) -conjugated anti-mouse antibody (1:5000) for 1 h at room temperature. After washing again with PBST, the membranes were developed by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) using the ChemoCam imager (Intas, Göttingen, Germany). Densitometric quantification was performed using Image J Software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) and normalization to the corresponding beta actin levels.

RNA isolation and qRT-PCR

In order to investigate MGMT mRNA expression, total RNA was isolated from cells using Quick-RNA MiniPrep kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA) according to the instructions of the manufacturer and concentrations were measured with a NanoDrop One spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA). Quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed using the QuantiTect SYBR Green RT-PCR Kit (Qiagen, Düsseldorf, Germany) in a 96 well format on StepOnePlus™ Real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA). Ubiquitin C (UBC) and hypoxanthine phosphoribosyl-transferase 1 (HPRT1) were used as endogenous normalization controls. The sequences of primers are shown in Supplementary Table S2.

Cell viability assay

T98G and LN18 cells were seeded at a density of 2.500 cells/well in triplicate in 96 well plates and cultured for 24 h. Subsequently, cells were treated with TMZ at the indicated concentrations for 144 h. The cell viability was determined by adding Alamar blue reagent (1:10) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) into each well and incubation for 2 h at 37°C. Fluorescence was measured at 560 nm excitation and 590 nm emission wavelengths using a fluorescence spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices, St, San Jose, CA, USA).

Flow cytometric analysis of cell death

Apoptotic cells are characterized by DNA fragmentation and loss of nuclear DNA content among other typical signs [10]. DNA-fragmentation of propidium iodide (PI)-stained nuclei was measured by flow cytometric analysis on a FACSCanto II (Becton Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany) according to the previously described protocol [10]. Briefly, cells were seeded at 20.000 cells per well in 24 wells plates and cultured for 24 h. Then, the medium was replaced with medium containing DMSO or TMZ at the indicated concentrations and the cells were cultured for an additional 72 or 144 h. Thereafter, the cells were harvested and centrifuged for 5 min, 1300 rpm at 4°C, resuspended in PI staining buffer (50 µg/ml propidium iodide, 0.05 % Triton-X 100, 0.05 % trisodium citrate dihydrate) and incubated for 1 h at 4°C. The data were analyzed using FlowJo Software (Ashland, OR, USA). The rates of specific DNA fragmentation rates were calculated by the following equation: 100 × (experimental DNA fragmentation (%) - spontaneous DNA fragmentation (%))/(100% - spontaneous DNA fragmentation (%)).

DNA extraction, bisulfite conversion, and pyrosequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted from different gRNA transgenic cell lines using DNA lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 100 mM EDTA pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 1 % SDS) supplemented with Proteinase K (20 mg/ml). Briefly, the cell pellet was incubated with 500 µl DNA lysis buffer and 12.5 µl Proteinase K at 55°C overnight. The next day, 210 µl saturated NaCl solution (5 M) was added and centrifuged for 30 min. Then, the supernatant was transferred into a new tube, mixed with 700 µl isopropanol, and incubated for 10 min at room temperature. Samples were then centrifuged for another 30 min, the supernatant was discarded and the pellet was washed with 70% ethanol followed by another centrifugation step for 30 min. After this step, the supernatant was discarded and the dried DNA pellet was dissolved in TE buffer (1 mM EDTA pH 8.0, 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0) and stored at 4°C. All centrifugation steps were performed at 14000 rpm at room temperature.

Bisulfite-treated DNA samples were prepared using DNA Methylation-Gold kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, US) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Specific regions of the MGMT promoter were amplified with biotinylated primers using PyroMark PCR kit (Qiagen, Düsseldorf, Germany). Pyrosequencing was performed using PyroMark Gold Q96 Reagents on the PyroMark Q24 Sequencer System (Qiagen, Düsseldorf, Germany) according to the manufacturer's recommendation. The data of pyrosequencing were analyzed by PyroMark Q24 Software (Qiagen, Düsseldorf, Germany). The sequence of primers, conditions for PCR amplification, and pyrosequencing assays are shown in Supplementary Table S3.

Global DNA methylation assay

The MethylFlash Global DNA methylation (5-mC) ELISA kit (Epigentek, Farmingdale, NY USA) was used to colorimetrically quantify the global DNA methylation status of the cell lines by specifically measuring the levels of 5-methylcytosine (5-mC). The optical density was measured at 450 nm using a SPECTROstar Nano absorbance reader (BMG, Ortenberg, Germany). The percentage of methylated DNA is proportional to the OD intensity measured. To calculate the fraction of methylated cytosines, the ODs are referenced to a standard curve set in parallel. The samples were measured in duplicate in three independent experiments.

DNA methylation profiling

Genomic DNA samples of three control EgRNA and three gRNA10 edited T98G cell lines were transferred to the Core Facility, University of Bonn, Germany. Each sample was purified using spin columns (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), and the DNA quantity and quality were assessed (Dropsense96, Trinean, Gentbrugge, Belgium). Bisulfite-conversion was carried out using the Epitect 96 Bisulfite Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), and 300 ng of converted DNA were hybridized to Illumina Infinium MethylationEPIC 850K BeadChips (Illumina, San Diego, CA), following the manufacturer's instructions. Methylation profiles were exported from Illumina GenomeStudio as IDAT files. The Sesame Bioconductor package v 1.18.3 (R version 3.4; Bioconductor version 3.17) was utilized for quality control, differential methylation analysis, and visualization.

Statistics

GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) was used to perform all statistical analyses. Student's t test or multiple t test was conducted to analyze the comparisons between two groups while one-way ANOVA was performed to analyze the differences among three groups. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) from at least three independent experiments.

Results

MGMT expression in established human TMZ-resistant glioblastoma cell lines

For MGMT gene silencing, three established human glioblastoma cell lines (LN18, T98G, and U138MG) known to be resistant to TMZ were initially selected to study their endogenous MGMT expression. Western blot analysis of cell lysates revealed a high MGMT expression in the glioblastoma cell lines T98G and LN18 (Fig. 1A). In contrast, the U138MG cell line showed only a very weak expression of MGMT and was excluded from further experiments (Fig. 1A). To test the susceptibility of T98G and LN18 cells to TMZ, cells were treated with different concentrations of TMZ (50, 100, 200, 400, 800 and 1000 µM) and cell viability was measured 144 h after TMZ exposure using the Alamar Blue assay. T98G and LN18 cells exhibited a dose-dependent decrease in viability (Fig. 1B) with 50% growth-inhibitory concentrations (IC50) values of 475.6 µM and 424.7 µM for T98G and LN18 cells, respectively (Fig.1C).

Fig. 1.

Characterization of different glioblastoma wild-type cell lines. (A) Western blot analysis of endogenous MGMT and actin expression in whole cell lysates prepared from T98G, LN18, and U138MG wild-type cells. (B) Cell viability of T98G and LN18 wild-type cells treated with increasing concentrations of TMZ (0, 50, 100, 200, 400, 800, and 1000 µM) for 144 h using the Alamar blue assay. (C) Calculated IC50 values for TMZ of T98G (blue) and LN18 (red) wild-type cells treated with increasing concentrations of TMZ. Results are averaged from triplicates and are expressed as the mean ± SD. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

Generation of glioblastoma cell lines with increased methylation of CpG sites in the MGMT promoter

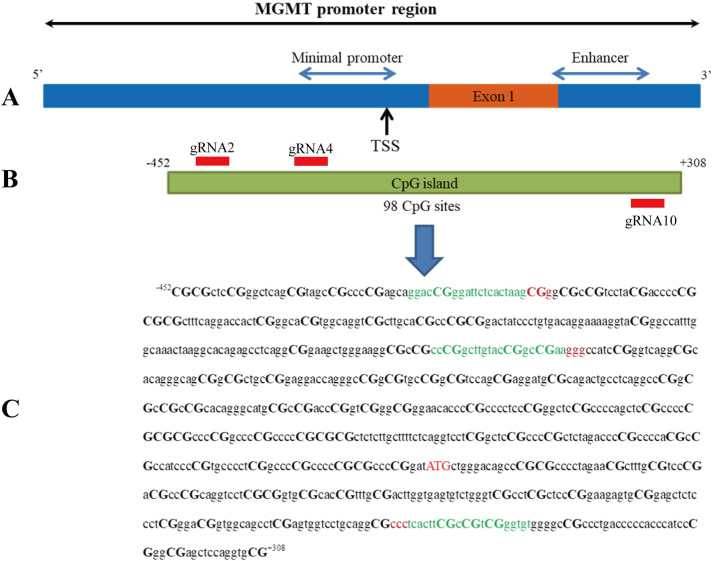

To achieve efficient editing of the CpG island (CGI), three individual guide RNAs (gRNA2, gRNA4, and gRNA10) targeting three specific regions distributed across the CGI of the MGMT promoter were selected (Fig. 2A, B). T98G cells were then stably co-transfected with the CRISPRoff vector expressing dCas9-DNMT3A/3L and one of each gRNA targeting the MGMT promoter region (Fig. 2B, C). An empty guide RNA vector (EgRNA) co-transfected with CRISPRoff vector in T98G cells served as the negative control. Several single T98G clonal lines stably expressing different gRNAs were isolated and analyzed for MGMT expression by Western blot analysis. T98G cell lines stably expressing gRNA2 showed a significant decrease in MGMT expression by approximately 50% (Supplementary Fig. S1A), while T98G clonal cell lines edited with sgRN4 showed no altered MGMT expression (data not shown). The strongest repressive effect was observed in T98G clonal cell lines stably expressing gRNA10 which showed a decrease in MGMT expression of approximately 60% compared to control cells stably transfected with EgRNA control (Fig. 3A, B). Also, quantitative RT-PCR analysis confirmed significantly decreased MGMT mRNA levels in T98G cells edited with gRNA10 by approximately 60% (Fig. 3C). To verify whether MGMT expression can also be successfully repressed in another TMZ-resistant cell line by CRISPR-based editing of DNA methylation, LN18 cells were stably transfected with gRNA10 and CRISPRoff. Surprisingly, compared to T98G, much stronger repression of the MGMT expression was achieved in LN18 cell lines stably expressing gRNA10. Selected clonal LN18 cell lines exhibited almost complete repression of the endogenous MGMT expression in both Western blot and qRT-PCR analysis (Fig. 3A, C). Taken together, these findings demonstrate that CRISPR-mediated DNA methylation of the MGMT promoter enables efficient silencing of the endogenous MGMT expression in TMZ-resistant glioblastoma cell lines.

Fig. 2.

Schematic representation of the epigenetically targeted region of the MGMT gene promoter. (A) Structure of the MGMT promoter region and location of the minimal promoter (-69 to +19) and enhancer (+143 to +202) (blue arrows), as well as the transcriptional start site (TSS +1, black arrow) and exon 1 (orange box). (B) Location of the CpG island with 98 CpG sites in the MGMT promoter region. (C) DNA sequence of the CpG island (-452 to +308) in the MGMT promoter region; CpG sites are shown in capital letters, the sequences and location of the gRNAs used are marked in green and the PAM motifs are in red.

Fig. 3.

MGMT protein and mRNA expression levels of edited glioblastoma cell lines. (A) Representative Western blot analysis of MGMT and actin expression in whole cell lysates of isolated T98G and LN18 clonal cell lines stably expressing empty gRNA (EgRNA) or gRNA10. (B) The relative protein amounts of MGMT were detected by Western blots and quantitated by densitometry. The MGMT levels were normalized to the corresponding actin levels. (C) Quantitative RT PCR of MGMT mRNA expression levels in EgRNA or gRNA10 stably expressing T98G and LN18 cell lines, respectively. The data were normalized to the housekeeping genes ubiquitin C and hypoxanthine phosphoribosyl-transferase 1 (see Materials & Methods). Results are averaged from triplicates and are expressed as the mean ± SD. Data are representative of three independent experiments. ****P<0.0001, ***P<0.001.

Downregulation of MGMT expression increases the cytotoxicity of TMZ in glioblastoma cell lines

To test whether the silenced glioblastoma cell lines also show an altered sensitivity to TMZ, the gRNA10 edited cell lines of T98G and LN18 were exposed to different concentrations of TMZ for 144 h and their viability was measured using the Alamar Blue assay. Compared to the corresponding EgRNA control cell lines, the cytotoxicity of TMZ in gRNA10 expressing T98G and LN18 cell lines increased significantly (Fig. 4A, B) resulting in strongly reduced IC50 values (110.9 µM vs 498.9 µM in T98G cells, 8.5 µM vs 386.5 µM in LN18 cells). Also, in T98G clonal cell lines stably expressing gRNA2, a significant reduction of the IC50 value for TMZ was observed compared to EgRNA control albeit to a much lower extent (437.2 µM vs 619.0 µM) (Supplementary Fig. S1C and D). The findings with the silenced T98G and LN18 cell lines clearly confirmed the correlation between TMZ resistance and MGMT expression.

Fig. 4.

Targeted editing of the CGI in the MGMT promoter increases the cytotoxicity of TMZ and reduces the IC50 values for TMZ in gRNA10 expressing T98G and LN18 cell lines. (A) T98G cells stably expressing empty guide RNA (EgRNA) or gRNA10 were treated with increasing concentrations of TMZ (50, 100, 200, 400, 800, and 1000 µM) for 144 h, and cell viability was measured using Alamar blue assay (left). Calculated IC50 values of TMZ for EgRNA and gRNA10 expressing T98G clonal cell lines (right). (B) LN18 cells stably expressing EgRNA or gRNA10 were treated with increasing concentrations of TMZ (10, 25, 50, 100, 200, 400, 800, and 1000 µM) for 144 h, and cell viability was measured using Alamar blue (left). Calculated IC50 values of TMZ for EgRNA and gRNA10 expressing LN29 clonal cell lines (right). Data are shown as mean ± SD of values from three independent experiments with each of three replicates. ****P<0.0001.

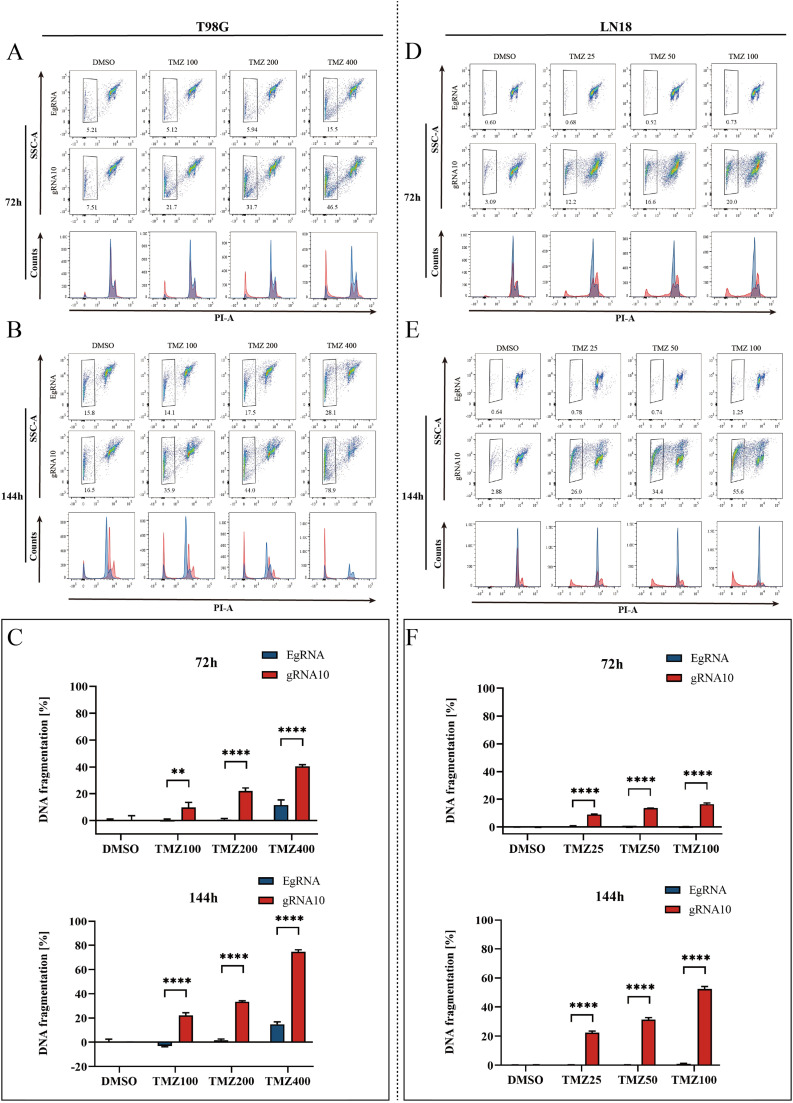

Capability of TMZ to induce cell death is restored in edited glioblastoma cell lines

The significant reduction of the IC50 values for TMZ in the modified glioblastoma cell lines indicates that targeted DNA methylation of the MGMT promoter can restore the capability of TMZ to induce cell death in TMZ-resistant glioblastoma cell lines. To study the TMZ-induced cell death in more detail, gRNA10 expressing cell lines of T98G and LN18 cells were treated for 72 h and 144 h with different concentrations of TMZ (100, 200, and 400 µM for T98G; 25, 50, and 100 µM for LN18), and DNA fragmentation was measured as readout reflecting cell death induction by flow cytometry after propidium iodide staining of the cell nuclei (Fig. 5). As expected, TMZ increased the percentage of cell death in a concentration- and time-dependent manner in all glioblastoma cell lines. For T98G cells stably expressing gRNA10, the percentage of DNA fragmentation increased up to almost threefold at the highest TMZ concentration (400 µM) after 72 h and displayed the highest increase in the proportion of sub-G1/dead cells after 144 h each compared to the respective T98G EgRNA control cell line (Fig. 5A–C). Interestingly, LN18 cells stably expressing gRNA10 showed a significantly increased cytotoxicity already at 100 µM TMZ with 20 % cell death after 72 h and 55 % cell death after 144 h each compared to the respective LN18 EgRNA control cell line; at the TMZ concentrations tested, virtually no induction of cytotoxicity or change in cell viability was detectable in LN18 EgRNA control cell line (Fig. 5D–F). Also, in gRNA2 stably expressing T98G cell lines, a significantly increased percentage of cell death was observed compared to the EgRNA control cell line after treating the cells with 400 µM TMZ for 72 h and 144 h (Supplementary Fig. S1E, F). Thus, targeted DNA methylation of the MGMT promoter is sufficient to overcome the TMZ resistance of established glioblastoma cell lines and induce cell death by TMZ.

Fig. 5.

Targeted methylation of the MGMT promoter sensitizes TMZ-resistant glioblastoma cells to TMZ-induced apoptotic cell death. (A and B) Representative density plots (upper) and histograms (lower) from flow cytometric analysis of T98G cells stably expressing EgRNA or gRNA10 treated with increasing concentrations of TMZ (100, 200, and 400 µM) or vehicle control (DMSO) for 72 h (A) or 144 h (B). The percentage of DNA fragmentation of propidium iodide (PI)-stained nuclei under the different concentrations of TMZ for 72 h (A) or 144 h (B) is indicated in the plots, respectively. In the overlays of the histograms, gRNA10 expressing T98G cells are shown in red, and EgRNA expressing T98G cells in blue. (C) Histograms showing the specific DNA fragmentation rates in T98G cell lines stably expressing EgRNA or gRNA10 in response to different concentrations of TMZ for 72 h (left) or 144 h (right), respectively. (D and E) Representative density plots (upper) and histograms (lower) from flow cytometric analysis of LN18 cells stably expressing EgRNA or gRNA10 treated with increasing concentrations of TMZ (25, 50, and 100 µM) or vehicle control (DMSO) for 72 h (D) or 144 h (E). The percentage of DNA fragmentation of PI-stained nuclei in response to different concentrations of TMZ for 72 h (D) or 144 h (E) is indicated in the plots, respectively. In the overlays of the histograms, gRNA10 expressing LN18 cells are shown in red, and EgRNA expressing LN18 cells in blue. (F) Specific DNA fragmentation rates of LN18 cell lines stably expressing EgRNA or gRNA10 in response to the treatment with TMZ for 72h (left) or 144h (right) is shown in the histograms. Data are shown as mean ± SD of values from three independent experiments with each of three replicates. ****P<0.0001, **P<0.01. TMZ, temozolomide; PI, propidium iodide; SSC-A, side scatter area, EgRNA, empty gRNA.

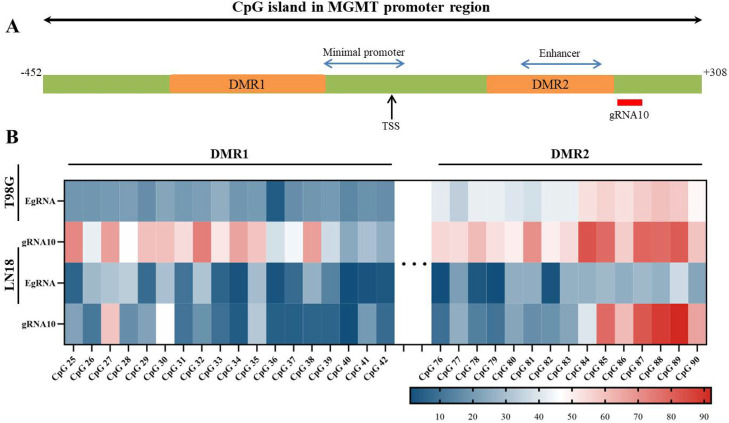

Methylation status of the CGI in the MGMT promoter of the edited glioblastoma cell lines

To investigate which CpG sites were methylated by CRISPRoff-mediated editing, we measured the DNA methylation levels of two transcriptionally critical regions, CpG25-42 in DMR1 and CpG76-90 in DMR2 (Fig. 6A), in the modified T98G and LN18 cell lines stably expressing gRNA10. Compared to the respective EgRNA control cell lines, the methylation levels in DMR2 particularly of CpGs 84-90 were significantly increased in both gRNA10 expressing T98G and LN18 cell lines (Fig. 6B). Interestingly, a significantly enhanced methylation of CpG 25-38 in the DMR1 region was found only in the gRNA10 edited T98G cell line while in gRNA10 edited LN18 only a few CpG sites in DMR1 showed increased methylation levels (Fig. 6B). In contrast, T98G cells edited with gRNA2 showed significantly increased methylation of CpG sites in the DMR1 region only but no significant methylation changes in the DMR2 region (Supplementary Fig. S1G). Together with the weaker effect on MGMT expression found in gRNA2 expressing T98G cells (Supplementary Fig. S1A, B), these findings indicate that methylation of CpG sites in DMR2 has a greater impact in regulating MGMT expression than methylation of DMR1. Thus, the most significant changes in MGMT expression and mean methylation were achieved by gRNA10-mediated methylation of the DMR2 region in both edited T98G and LN18 glioblastoma cell lines.

Fig. 6.

Differential DNA methylation pattern of the CpG island in the MGMT promoter of the established edited glioblastoma cell lines. (A) Schematic showing the location of the differentially methylated region 1 and 2 (DMR1 and 2, orange) and target site of gRNA10 (red) within the CpG island of MGMT promoter. The location of the minimal promoter and enhancer (blue arrows) and the position of the transcription start site (TSS, black arrow) are indicated. (B) Heatmap showing the methylation level of single CpG sites in different T98G and LN18 cell lines stably expressing EgRNA or gRNA10 determined by pyrosequencing. Each column represents one CpG site, CpG25-42 in the DMR1 region and CpG76-90 in the DMR2 region; each row represents one edited clonal cell line. Higher and lower rates of methylation are shown in red and blue, respectively. Data are shown as mean ± SD of values from two independent experiments with each of three replicates. EgRNA, empty gRNA.

Evaluation of the potential off-target effect in edited glioblastoma cell lines

The findings demonstrate that the CRISPRoff editing approach with gRNA10 efficiently methylates CpG dinucleotides flanking its target sites at the MGMT promoter and is associated with transcriptional repression of MGMT expression. However, epigenome editing using dCas9 methyltransferases can cause off-target methylation of promoter regions, 5’ untranslated regions, and CpG islands [11]. To verify the target specificity of the RNA-guided methylation, we performed an immunoassay to quantify the global DNA methylation by measuring the percentage of 5’-methylcytosine using DNA samples of the respective parental cell lines, the corresponding EgRNA control, and the gRNA10 expressing cell lines of T98G and LN18, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S3A). The results for wild type (WT), control (EgRNA), and the gRNA10 cell lines did not reveal significantly altered global methylation in either the T98G (0.15% vs 0.16% vs 0.18%, respectively) or LN18 cell lines (0.35% vs 0.34% vs 0.32%, respectively).

To further evaluate the potential genome-wide off-target methylation status of the gRNA10-CRISPRoff transgene, we arrayed gRNA10 stably expressing T98G cell line and its corresponding EgRNA control using the Illumina EPIC (850K) bead array and analyzed the potential off-target sites of gRNA10 predicted by the tool CRISPOR included in the UCSC genome browser (Supplementary Table S4). Out of seventeen predicted off-target regions, only eleven regions were covered by the Illumina EPIC array probes. All eleven regions showed no signs of differential methylation between control and edited T98G cell lines (Supplementary Fig. S3B-L). Although six regions were uncovered by methylation probes, the overall result indicates no off-target methylation was triggered or observed in the edited T98G cell lines. Together with the unchanged global DNA methylation in the edited lines of T98G and LN18 these findings suggest that off-target effects are minimal and that targeted RNA-guided methylation of the MGMT promoter may represent a possible approach to reduce MGMT expression and TMZ resistance of glioblastomas.

Discussion

Although TMZ is commonly used as standard therapy for glioblastoma, TMZ chemotherapy is compromised by the development of resistance in nearly 40% of all patients with glioblastoma [12]. The expression level of MGMT is an important factor associated with resistance of TMZ in glioblastoma. In this study, targeted editing of DNA methylation in the MGMT promoter was sufficient to overcome TMZ resistance of known TMZ-resistant glioblastoma cell lines and induce cell death by TMZ. Our study identifies targeted RNA-guided methylation of the MGMT promoter as a promising tool to reduce MGMT expression and reverse TMZ resistance of glioblastoma.

The CRISPR/Cas9 system has become an important technology for editing human genomes. Originally discovered as an adaptive immune system in prokaryotes consisting of a DNA endonuclease and a single guide RNA (gRNA), it has been widely used in glioblastoma to uncover the function of genes involved in tumor cell growth, suppression of apoptosis, induction of autophagy, deregulation of the immune response, cell migration and metastasis [13]. In recent years, modifications of the CRISPR/Cas9 system have been developed using catalytically inactive Cas9 (dCas9) for epigenetic editing in glioblastoma. For instance, Jameson et al. identified two enhancers within the first intron of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) gene which is frequently overexpressed in a variety of cancer types including glioblastoma [14,15]. Using a dCas9 protein fused to the Krüppel-associated box (dCas9-KRAB), the authors were able to target the enhancer elements and repress EGFR transcription by histone deacetylation [14]. In addition, glioblastoma progression was successfully suppressed with an RNA-guided CRISPR/dCas9 synergistic activation mediator system overexpressing full-length HECT domain-containing E3 ubiquitin ligase (HUWE1) [16]. HUWE1 is known to regulate the complex interaction between proliferation, differentiation, and DNA damage response [17], [18], [19], [20]. Here, we used a CRISPR/dCas9 (CRISPRoff) system in established glioblastoma cell lines to achieve targeted methylation of CpGs in the MGMT promoter by a methyltransferase (DNMT3A/3L) fused to dCas9. Individual guide RNAs targeting different regions of the MGMT promoter were studied for their capability to repress the endogenous MGMT expression. Using the CRISPRoff system we isolated several clonal cell lines of LN18 and T98G showing a strong to almost complete reduction in their endogenous MGMT expression at both the mRNA and protein levels, especially gRNA10 stably expressing clonal cell lines. Moreover, expression of MGMT was stably repressed over multiple generations in the epigenetically silenced clonal cell lines of T98G and LN18 for at least 10-15 passages (data not shown).

As a cellular DNA repair protein, MGMT is regulated by multiple factors including transcription factors, microRNAs, histone modifications such as acetylation, and especially methylation of the MGMT promoter region [21]. Previous studies have linked high levels of MGMT activity to resistance to alkylating agents such as TMZ in tumor tissue, and are used to predict its therapeutic effect [22,23]. Given the enormous importance of MGMT in TMZ resistance, a variety of approaches have already been used to improve the sensitivity of TMZ. A common approach for the treatment of TMZ-resistant glioblastoma cells consists of a combination of different compounds that inhibit MGMT or suppress its expression. Recently, NCT503 a highly selective inhibitor of the rate-limiting enzyme of serine biosynthesis was shown to inhibit the expression of MGMT and synergistically enhance the efficiency of TMZ [24]. Interestingly, treatment with NCT503 did not result in any change of methylation levels in the MGMT promoter, and other pathways such as the Wnt/ß-catenin pathways are likely involved in the regulation of MGMT expression [24]. In addition, a small molecule compound, EPIC-0412, was discovered which enhanced the TMZ sensitivity in glioblastoma by acting on the p21-E2F1 DNA damage repair axis and ATF3-p-p65-MGMT axis [25]. In combination with TMZ, EPIC-0412 synergistically reduced the viability of glioblastoma cells and reversed TMZ resistance. Similarly, small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) targeting transcription of MGMT succeeded in suppressing the expression of MGMT and increased the cytotoxicity of TMZ in T98G glioma cells [26].

In our study, we investigated whether CRISPRoff-based hypermethylation of the MGMT promoter is able to enhance the sensitivity for TMZ in resistant glioblastoma cell lines. The IC50 values for TMZ which were initially measured in the parental cell lines of T98G (476 µM) and LN18 (425 µM) were comparable to those reported previously for T98G (502 µM) and LN18 (511 µM) [27,28]. Using CRISPRoff-mediated methylation of MGMT promoter CGI in the TMZ-resistant glioblastoma cell lines impressively decreased the IC50 values of TMZ by 78% and 98% in gRNA10 stably expressing T98G and LN18 cell lines, respectively. In addition, the increased sensitivity to TMZ of the gRNA10 edited cell lines could also be confirmed by DNA fragmentation analysis using propidium iodide staining and flow cytometry. The epigenetically silenced different gRNA10 clonal cell lines showed significantly higher levels of DNA fragmentation upon treatment with a lower concentration of TMZ compared to the respective control cell lines supporting an enhanced induction of cell death and loss of nuclear DNA content by TMZ treatment. Interestingly, the cytotoxic effect of TMZ in gRNA2 stably expressing T98G cell line was less pronounced, which can be explained most likely by an insufficient reduction of the MGMT expression and still too high residual expression of MGMT. During the DNA repair process, one MGMT molecule irreversibly removes only one alkyl group from the O6 position of guanine to its cysteine residue; thus, the capacity of the DNA repair depends on the amount of MGMT [29].

Recently, two distinct regions, DMR1 and DMR2 (differentially methylated regions 1 and 2), have been identified whose methylation status strongly correlates with MGMT expression [29]. In addition, Bady et al. demonstrated that methylation of the DMR1 and DMR2 region in the MGMT promoter is associated with improved overall survival of patients treated with alkylating agents [30]. Here, we tested individual gRNAs targeting three different regions of the CGI in the MGMT promoter and evaluated their capability to repress endogenous MGMT expression. While one gRNA (gRNA4) showed no repressive effect at all, two gRNAs (gRNA2, 10) targeting both ends of the CpG island, showed a different degree of reduction of their endogenous MGMT expression. In this regard, the location of the gRNA-targeted sequence appears to play an important role for regulating MGMT expression. gRNA2 binds to a DNA sequence on the sense strand in the starting region of CGI in the MGMT promoter and caused increased methylation of multiple CpG sites in the DMR1 region decreasing MGMT expression by 50%. gRNA10, which targets a DNA sequence at the end of CGI on the antisense strand, mediated increased methylation of the DMR2 region resulting in a strong to almost complete reduction of MGMT expression in both T98G and LN18 glioblastoma cell lines stably expressing gRNA10. In particular, we found hypermethylation of CpG84-89 sites in the DMR2 region of gRNA10 stably expressing T98G and LN18 glioblastoma cell lines. These CpG sites are located within the enhancer region of the MGMT promoter and 5’upstream of the gene region targeted by gRNA10. Consistent with our results, Malley et al. demonstrated that methylation of CpG83-87 and particularly CpG89 correlates with the transcriptional control of MGMT expression [29]. These findings show that by using CRISPRoff and one specific gRNA, efficient methylation of CpGs in the DMR2 region and silencing of the MGMT expression can be achieved in formerly TMZ-resistant glioblastoma cell lines.

However, although the global methylation levels of the silenced, parental, and control cell lines of T98G and LN18 did not exhibit significant changes in the genome-wide methylation status, off-target effects can occur at unintended sites in the genome and lead to potentially adverse effects. In the 850K methylation analysis, no differential methylation of the predicted off-target sites was detected in gRNA10 stably expressing T98G clonal cell for the probes present on the array suggesting that no off-target methylation was induced in the edited T98G cell lines except the intended one. Nevertheless, previous reports have shown that DNMT3A and DNMT3B linked to dCas9 can result in a significant increase in off-target methylation [31,32]. Therefore, the methylation editing technology needs to be further developed and improved before it reaches a clinical stage. For example, it has been reported that the use of recombinant Cas9 protein results in much lower off-target editing than expression-based approaches [33]. In addition, the frequency of off-target effects can be minimized by ribonucleoprotein (RNP)-based methods to limit the exposure of the genome to active Cas9 complexes. Recently, Yan et al. developed a noninvasive CRISPR/Cas9 brain nano-delivery system that could be used in combination with RNPs to limit off-target effects and provide excellent gene editing efficiencies [34]. In conclusion, our study demonstrates that CRISPRoff-based targeted methylation of the MGMT promoter is capable to downregulate MGMT expression and to enhance susceptibility for TMZ of TMZ-resistant glioblastoma cell lines, and may provide an experimental basis for potential use as a therapeutic strategy.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Xinyu Han: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Validation, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. Mohammed O.E. Abdallah: Conceptualization, Data curation, Software, Writing – review & editing. Peter Breuer: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. Fabian Stahl: Conceptualization, Methodology. Yousuf Bakhit: Writing – review & editing. Anna-Laura Potthoff: Data curation, Software, Writing – review & editing. Barbara E.F. Pregler: Data curation, Software, Writing – review & editing. Matthias Schneider: Resources, Writing – review & editing. Andreas Waha: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Resources, Writing – review & editing. Ullrich Wüllner: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Bernd O. Evert: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Supervision.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Verena Dreschmann and Hassan Kazneh for their excellent technical assistance.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.neo.2023.100929.

Contributor Information

Ullrich Wüllner, Email: ullrich.wuellner@dzne.de.

Bernd O. Evert, Email: b.evert@uni-bonn.de.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Yang K., Wu Z., Zhang H., Zhang N., Wu W., Wang Z., Dai Z., Zhang X., Zhang L., Peng Y., Ye W., Zeng W., Liu Z., Cheng Q. Glioma targeted therapy: insight into future of molecular approaches. Mol. Cancer. 2022;21:39. doi: 10.1186/s12943-022-01513-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wen P.Y., Weller M., Lee E.Q., Alexander B.M., Barnholtz-Sloan J.S., Barthel F.P., Batchelor T.T., Bindra R.S., Chang S.M., Chiocca E.A., Cloughesy T.F., DeGroot J.F., Galanis E., Gilbert M.R., Hegi M.E., Horbinski C., Huang R.Y., Lassman A.B., Le Rhun E., Lim M., Mehta M.P., Mellinghoff I.K., Minniti G., Nathanson D., Platten M., Preusser M., Roth P., Sanson M., Schiff D., Short S.C., Taphoorn M.J.B., Tonn J.C., Tsang J., Verhaak R.G.W., von Deimling A., Wick W., Zadeh G., Reardon D.A., Aldape K.D., van den Bent M.J. Glioblastoma in adults: a society for Neuro-Oncology (SNO) and European Society of Neuro-Oncology (EANO) consensus review on current management and future directions. Neuro Oncol. 2020;22:1073–1113. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noaa106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Della Monica R., Cuomo M., Buonaiuto M., Costabile D., Franca R.A., Del Basso De Caro M., Catapano G., Chiariotti L., Visconti R. MGMT and whole-genome DNA methylation impacts on diagnosis, prognosis and therapy of glioblastoma multiforme. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022:23. doi: 10.3390/ijms23137148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mansouri A., Hachem L.D., Mansouri S., Nassiri F., Laperriere N.J., Xia D., Lindeman N.I., Wen P.Y., Chakravarti A., Mehta M.P., Hegi M.E., Stupp R., Aldape K.D., Zadeh G. MGMT promoter methylation status testing to guide therapy for glioblastoma: refining the approach based on emerging evidence and current challenges. Neuro Oncol. 2019;21:167–178. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noy132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Christmann M., Nagel G., Horn S., Krahn U., Wiewrodt D., Sommer C., Kaina B. MGMT activity, promoter methylation and immunohistochemistry of pretreatment and recurrent malignant gliomas: a comparative study on astrocytoma and glioblastoma. Int. J. Cancer. 2010;127:2106–2118. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hegi M.E., Diserens A.C., Gorlia T., Hamou M.F., de Tribolet N., Weller M., Kros J.M., Hainfellner J.A., Mason W., Mariani L., Bromberg J.E., Hau P., Mirimanoff R.O., Cairncross J.G., Janzer R.C., Stupp R. MGMT gene silencing and benefit from temozolomide in glioblastoma. New Engl. J. Med. 2005;352:997–1003. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hegi M.E., Liu L., Herman J.G., Stupp R., Wick W., Weller M., Mehta M.P., Gilbert M.R. Correlation of O6-methylguanine methyltransferase (MGMT) promoter methylation with clinical outcomes in glioblastoma and clinical strategies to modulate MGMT activity. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26:4189–4199. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.5964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stupp R., Hegi M.E., Mason W.P., van den M.J., Bent M.J., Taphoorn R.C., Janzer S.K., Ludwin A., Allgeier B., Fisher K., Belanger P., Hau A.A., Brandes J., Gijtenbeek C., Marosi C.J., Vecht K., Mokhtari P., Wesseling S., Villa E., Eisenhauer T., Gorlia M., Weller D., Lacombe J.G., Cairncross R.O., Mirimanoff R. European organisation for, T. treatment of cancer brain, G. radiation oncology, G. national cancer institute of Canada clinical trials, effects of radiotherapy with concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide versus radiotherapy alone on survival in glioblastoma in a randomised phase III study: 5-year analysis of the EORTC-NCIC trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:459–466. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nunez J.K., Chen J., Pommier G.C., Cogan J.Z., Replogle J.M., Adriaens C., Ramadoss G.N., Shi Q., Hung K.L., Samelson A.J., Pogson A.N., Kim J.Y.S., Chung A., Leonetti M.D., Chang H.Y., Kampmann M., Bernstein B.E., Hovestadt V., Gilbert L.A., Weissman J.S. Genome-wide programmable transcriptional memory by CRISPR-based epigenome editing. Cell. 2021;184:2503–2519. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.03.025. e2517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Riccardi C., Nicoletti I. Analysis of apoptosis by propidium iodide staining and flow cytometry. Nat. Protoc. 2006;1:1458–1461. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin J., Wong K.C. Off-target predictions in CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing using deep learning. Bioinformatics. 2018;34:i656–i663. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stupp R., Mason W.P., van den M.J., Bent M., Weller B., Fisher M.J., Taphoorn K., Belanger A.A., Brandes C., Marosi U., Bogdahn J., Curschmann R.C., Janzer S.K., Ludwin T., Gorlia A., Allgeier D., Lacombe J.G., Cairncross E., Eisenhauer R.O., Mirimanoff R. European organisation for, T. treatment of cancer brain, G. radiotherapy, G. national cancer institute of Canada clinical trials, radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. New Engl. J. Med. 2005;352:987–996. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.N. Al-Sammarraie, S.K. Ray, Applications of CRISPR-Cas9 technology to genome editing in glioblastoma multiforme, n.a, 10 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Jameson N.M., Ma J., Benitez J., Izurieta A., Han J.Y., Mendez R., Parisian A., Furnari F. Intron 1-mediated regulation of EGFR expression in EGFR-dependent malignancies is mediated by AP-1 and BET proteins. Mol. Cancer Res. 2019;17:2208–2220. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-19-0747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.D.S. Salomon, R. Brandt, F. Ciardiello, N. Normanno, Epidermal growth factor-related peptides and their receptors in human malignancies, #N/A, 19 (1995) 183–232. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Yuan Y., Wang L.H., Zhao X.X., Wang J., Zhang M.S., Ma Q.H., Wei S., Yan Z.X., Cheng Y., Chen X.Q., Zou H.B., Ge J., Wang Y., Zhang X., Cui Y.H., Luo T., Bian X.W. The E3 ubiquitin ligase HUWE1 acts through the N-Myc-DLL1-NOTCH1 signaling axis to suppress glioblastoma progression. Cancer Commun. (Lond.) 2022;42:868–886. doi: 10.1002/cac2.12334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang J., Kan S., Huang B., Hao Z., Mak T.W., Zhong Q. Mule determines the apoptotic response to HDAC inhibitors by targeted ubiquitination and destruction of HDAC2. Genes Dev. 2011;25:2610–2618. doi: 10.1101/gad.170605.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inoue S., Hao Z., Elia A.J., Cescon D., Zhou L., Silvester J., Snow B., Harris I.S., Sasaki M., Li W.Y., Itsumi M., Yamamoto K., Ueda T., Dominguez-Brauer C., Gorrini C., Chio I.I., Haight J., You-Ten A., McCracken S., Wakeham A., Ghazarian D., Penn L.J., Melino G., Mak T.W. Mule/Huwe1/Arf-BP1 suppresses Ras-driven tumorigenesis by preventing c-Myc/Miz1-mediated down-regulation of p21 and p15. Genes Dev. 2013;27:1101–1114. doi: 10.1101/gad.214577.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kurokawa M., Kim J., Geradts J., Matsuura K., Liu L., Ran X., Xia W., Ribar T.J., Henao R., Dewhirst M.W., Kim W.J., Lucas J.E., Wang S., Spector N.L., Kornbluth S. A network of substrates of the E3 ubiquitin ligases MDM2 and HUWE1 control apoptosis independently of p53. Sci. Signal. 2013;6:ra32. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2003741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hao Z., Duncan G.S., Su Y.W., Li W.Y., Silvester J., Hong C., You H., Brenner D., Gorrini C., Haight J., Wakeham A., You-Ten A., McCracken S., Elia A., Li Q., Detmar J., Jurisicova A., Hobeika E., Reth M., Sheng Y., Lang P.A., Ohashi P.S., Zhong Q., Wang X., Mak T.W. The E3 ubiquitin ligase Mule acts through the ATM-p53 axis to maintain B lymphocyte homeostasis. J. Exp. Med. 2012;209:173–186. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nie E., Jin X., Miao F., Yu T., Zhi T., Shi Z., Wang Y., Zhang J., Xie M., You Y. TGF-beta1 modulates temozolomide resistance in glioblastoma via altered microRNA processing and elevated MGMT. Neuro Oncol. 2021;23:435–446. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noaa198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baer J.C., Freeman A.A., Newlands E.S., Watson A.J., Rafferty J.A., Margison G.P. Depletion of O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase correlates with potentiation of temozolomide and CCNU toxicity in human tumour cells. Br. J. Cancer. 1993;67:1299–1302. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1993.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Friedman H.S., Kerby T., Calvert H. Temozolomide and treatment of malignant glioma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2000;6:2585–2597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jin L., Kiang K.M., Cheng S.Y., Leung G.K. Pharmacological inhibition of serine synthesis enhances temozolomide efficacy by decreasing O(6)-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) expression and reactive oxygen species (ROS)-mediated DNA damage in glioblastoma. Lab. Invest. 2022;102:194–203. doi: 10.1038/s41374-021-00666-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao J., Yang S., Cui X., Wang Q., Yang E., Tong F., Hong B., Xiao M., Xin L., Xu C., Tan Y., Kang C. A novel compound EPIC-0412 reverses temozolomide resistance via inhibiting DNA repair/MGMT in glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2022 doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noac242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kato T., Natsume A., Toda H., Iwamizu H., Sugita T., Hachisu R., Watanabe R., Yuki K., Motomura K., Bankiewicz K., Wakabayashi T. Efficient delivery of liposome-mediated MGMT-siRNA reinforces the cytotoxity of temozolomide in GBM-initiating cells. Gene Ther. 2010;17:1363–1371. doi: 10.1038/gt.2010.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hermisson M., Klumpp A., Wick W., Wischhusen J., Nagel G., Roos W., Kaina B., Weller M. O6-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase and p53 status predict temozolomide sensitivity in human malignant glioma cells. J. Neurochem. 2006;96:766–776. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee S.Y. Temozolomide resistance in glioblastoma multiforme. Genes Dis. 2016;3:198–210. doi: 10.1016/j.gendis.2016.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Malley D.S., Hamoudi R.A., Kocialkowski S., Pearson D.M., Collins V.P., Ichimura K. A distinct region of the MGMT CpG island critical for transcriptional regulation is preferentially methylated in glioblastoma cells and xenografts. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;121:651–661. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0803-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bady P., Sciuscio D., Diserens A.C., Bloch J., van den Bent M.J., Marosi C., Dietrich P.Y., Weller M., Mariani L., Heppner F.L., McDonald D.R., Lacombe D., Stupp R., Delorenzi M., Hegi M.E. MGMT methylation analysis of glioblastoma on the Infinium methylation BeadChip identifies two distinct CpG regions associated with gene silencing and outcome, yielding a prediction model for comparisons across datasets, tumor grades, and CIMP-status. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;124:547–560. doi: 10.1007/s00401-012-1016-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kantor B., Tagliafierro L., Gu J., Zamora M.E., Ilich E., Grenier C., Huang Z.Y., Murphy S., Chiba-Falek O. Downregulation of SNCA expression by targeted editing of DNA methylation: a potential strategy for precision therapy in PD. Mol. Ther. 2018;26:2638–2649. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2018.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.L. Lin, Y. Liu, F. Xu, J. Huang, T.F. Daugaard, T.S. Petersen, B. Hansen, L. Ye, Q. Zhou, F. Fang, L. Yang, S. Li, L. Floe, K.T. Jensen, E. Shrock, F. Chen, H. Yang, J. Wang, X. Liu, X. Xu, L. Bolund, A.L. Nielsen, Y. Luo, Genome-wide determination of on-target and off-target characteristics for RNA-guided DNA methylation by dCas9 methyltransferases, #N/A, 7 (2018) 1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Vakulskas C.A., Behlke M.A. Evaluation and reduction of CRISPR Off-target cleavage events. Nucleic Acid Ther. 2019;29:167–174. doi: 10.1089/nat.2019.0790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zou Y., Sun X., Yang Q., Zheng M., Shimoni O., Ruan W., Wang Y., Zhang D., Yin J., Huang X., Tao W., Park J.B., Liang X.J., Leong K.W., Shi B. Blood-brain barrier-penetrating single CRISPR-Cas9 nanocapsules for effective and safe glioblastoma gene therapy. Sci. Adv. 2022;8:eabm8011. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abm8011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.