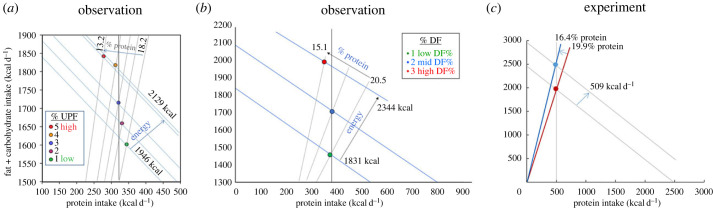

Figure 4.

Relationships between intake of highly processed foods, dietary macronutrient composition and energy intakes from diet surveillance studies (a,b) and a randomized control trial (c). (a) Respondents in the 2009–2010 NHANES cycles were partitioned into quintiles based on per cent contribution of ultra-processed foods (UPF) to daily energy intake. With increasing UPF, percentage protein decreased, fat, carbohydrate and energy intake increased, but protein intake varied little, as predicted by protein leverage (replotted from tables 2 and 3 in [97]). (b) Equivalent analysis of the Australian Adult Health and Nutrition Survey, in which respondents were partitioned into tertiles of discretionary food intake (modified from [13]). (c) Geometric plot of data from an inpatient randomized control trial in which subjects had ad libitum access to ultra-processed or unprocessed diets for 14 days. Diets were of equal caloric density (data are replotted from fig. 2 in [98]). Overall, subjects ingested a lower per cent protein and higher energy intake on the ultra-processed diet, yet absolute protein intake was the same.