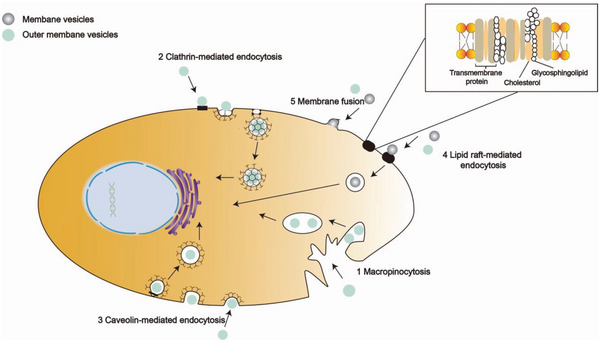

Figure 3.

Schematic illustration of BMVs entering the host cells. 1) Macropinocytosis, which is driven by actin that form cup‐shaped membrane ruffles. When the ruffles fold back, they enclose the BMV. The closure followed with pinching off from the plasma membrane give rise to irregularly shaped vesicles and the vesicle will be released into the lysosome. 2) Clathrin‐mediated endocytosis. BMV recruitment concentrates cargo molecules to the coated region of the plasma membrane. The assembling coat promotes membrane bending, which transforms the flat plasma membrane into a “clathrin‐coated pit”, subsequently releasing the nascent cargo‐filled vesicle and allowing it to be trafficked within the cell. 3) Caveolin‐mediated endocytosis. Lipid raft domains can also be enriched in caveolin and the oligomerization of caveolin allows the formation of caveolae. Similar to clathrin‐mediated endocytosis, dynamin is also required for the scission and internalization of caveolae, but caveolin‐mediated endocytosis has higher efficiency than CME. 4) Lipid raft‐mediated endocytosis requires small GTPases in a protein receptor‐independent fashion to accept BMV into cells. 5) Membrane fusion. The lipids of BMV fuse with the cell phospholipid bilayer and the contents of the vesicle are then released into the cytoplasm.