Abstract

Parents of three children with neurodevelopmental disorders and pica were taught to use a safety checklist to create pica-safe areas when transitioning to new locations. During baseline, no parent displayed pica-safe behavior, and their children attempted pica at moderate to high rates. After use of the checklist, parent pica-safe behavior increased, and instances of pica diminished to near zero. Results transferred to new contexts and additional substances associated with pica. Using the safety checklist appears to have aided parents in creating pica-safe environments to minimize pica.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40617-023-00798-w.

Keywords: Parent training, Pica, Safety checklist

Pica involves the persistent ingestion of non-food items (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Pica has been associated with poisoning, emergency surgery, choking, and death (McNaughten et al., 2017; Sturmey & Williams, 2016). The risk of this behavior is substantially increased for individuals with neurodevelopmental disorders (Fields et al., 2021). Research shows that a variety of behavioral interventions can be quite effective at reducing the pica of individuals with neurodevelopmental disorders (Hagopian et al., 2011). A preventative strategy to reduce pica rarely discussed in the literature is to eliminate the targeted stimuli from the environment (Williams & McAdam, 2012). Creating a pica-safe environment does not teach individuals to refrain from pica; however, it can (1) augment behavioral-based treatment packages by reducing inadvertent reinforcement of pica within and between sessions; and (2) increase safety during inevitable periods of low supervision.

Two studies describe creating pica-safe environments as part of multicomponent treatment programs. Fisher et al. (1994) described such a strategy in their discussion section, ancillary to the primary findings. Staff were reported to monitor inpatient and clients’ home environments for small and dangerous items that could be swallowed. Likewise, Williams et al. (2009) outlined a clinic-wide staff training program for pica. One component was the use of a safety checklist to sweep rooms for items that residents with pica might consume (e.g., loose threads, scrap paper, lint).

A preventative checklist may also benefit parents treating their children’s pica in outpatient clinics and in their homes. Several studies have indicated that home safety checklists can help parents prevent child injuries in their homes. For instance, Tertinger et al. (1984) developed the Home Accident Prevention Inventory (HAPI) to aid parents of neglected and abused children in securing their homes of hazardous materials accessible to children. Positive results from HAPI use were successfully replicated in two subsequent studies (Cordon et al., 1998; Metchikian et al., 1999). Thus, the purpose of this paper was to report on the effects of a safety checklist on parent pica-safe behavior and corresponding child pica.

Method

Participants and Settings

Three parent–child dyads participated. All children were diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder by a licensed professional, pica of infancy and childhood, and had been referred to an outpatient behavioral psychology clinic for the treatment of pica and other problem behaviors. No participant had experience with pica treatment prior to admission, and each had one or more admissions to an emergency room resulting from pica (e.g., bowel obstruction). At the time of participation, all children were in the initial stages of a pica treatment evaluation; however, clinically significant reductions had yet to be observed. Nancy was a 7-year-old female with additional diagnoses of Phelan-McDermid syndrome (SHANK 3 mutation) and epilepsy. She was on home–hospital instruction and received in-home therapy based on the principles of behavior for approximately 35 hr/week. She manded using a tablet-based system. Pica targets included small plastic toys, leaves, pebbles, animal droppings, and paper. Her attempts at pica were reported to occur almost constantly. Nancy’s mother was in her mid-30s, college-educated, and held a full-time management job.

Brian was a 7-year-old male diagnosed with disorder of the central nervous system (unspecified), profound intellectual disability, ADHD, stereotypic movement disorder with self-injurious behavior, and a sleep disorder. He was nonvocal and did not have a well-established mode of communication. Brian’s pica was reported to occur almost constantly, and routinely involved paper/cardboard, rocks, dirt, sand, mulch, liquids (any), paper clips, and hair ties or rubber bands. Brian’s father was in his early 40s, held an advanced degree, and worked full-time in a technology-based career.

Margo was a 13-year-old female diagnosed with moderate-severe intellectual disability, and disruptive behavior disorder. She was vocal, and manded using 1–3 word phrases. Margo attended a special education program in a public middle school. Margo’s pica was predominantly covert; she would discretely scavenge and hide items for later consumption. Her pica targets included wood, plastic toys, paint chips, foams, rubber cords, clothing threads, skin, and paper. Evidence of pica in the form of observed occurrence, property destruction, or foreign objects in her stool was observed 1–2 times per day. Margo’s mother was in her late 40s, single, held an advanced degree, and worked full-time in a science-related profession.

All participants’ pica functional analyses occurred in an outpatient clinic treatment room. Brian and Margo’s baseline, treatment, and extension sessions occurred in different areas of an outpatient clinic setting and office building (e.g., lobby, hallways, outdoor entryway, treatment rooms). Nancy’s baseline and training sessions occurred in the home via telehealth, and some extension sessions occurred in a hospital and surrounding outdoor areas.

Measurement and Interobserver Agreement

The primary dependent variable was parent pica-safe behavior, a composite of the following four parent behaviors: stopping at room threshold before entering, blocking child from entering room, scanning room for unsafe pica-related items, and then entering the room before the child to remove the item(s) or preventatively positioning their body between the child and the item(s). The checklist involved an additional step of using a pen to document the items removed. Because documenting was not applicable in baseline, it was not scored in treatment. Pica was defined as passing a nonnutritive item beyond the midline of one’s lips, with or without ingestion (e.g., blocked attempt). Percentage of occurrence for each behavior was calculated by summing the total number of trials in which the behavior occurred, by the total number of trials per session (five) and multiplying the quotient by 100.

A trained secondary observer collected data for 54.5% of Nancy’s sessions, 42.9% of Brian’s, and 82.5% of Margo’s, across baseline, training, and extension phases. Interobserver agreement was calculated using the trial-by-trial method for each behavior. The arithmetic mean interobserver agreement was 95.8% (range: 90%–100%) for Nancy’s mother and 95% (range: 80%–100%) for Nancy’s pica; 100% for Brian’s father and 100% for his pica; and 95.4% (range: 81.4%–100%) for Margo’s mother and 100% for her pica.

Procedures

Pretreatment Assessments

Prior to admission, parents listed substances associated with their child’s pica on an intake questionnaire (“What has your child consumed?”). Upon admission, parents generated a refined list of their child’s pica targets using the Pica and Related Behavior Inventory (Thomas, 2022), an empirically derived clinical tool for identifying substances associated with pica in the past 3 months. Safe, edible items that resembled the identified swallowed nonfood items were used as bait in each setting (e.g., dehydrated rice paper or noodles with food coloring for plastics, dried beans for animal droppings, salad leaves, unsalted dried seaweed, paper). All items and creations were approved by medical staff. Next, all participants participated in a functional analysis of pica as described by Piazza et al. (1998).

Treatment Evaluation

Each session consisted of five trials, and trials began when the parent or their child passed through a threshold, and ended upon the occurrence of pica, or when 60 s elapsed in the new location. In all sessions, rooms and areas were baited with two or three items in locations that differed from the prior session. Staff retrieved any items missed by parents at the end of trials. The treatment was evaluated using a nonconcurrent multiple baseline across-participants design (e.g., Watson & Workman, 1981).

Baseline

During baseline trials, parents were asked to transition with their child to a new location. Parents were informed that there were items associated with their child’s pica in the locations. No further instructions were provided.

Pica Safety Checklist

Parents were given a written checklist and instructed to read and follow the directions on the checklist. The checklist contained typed instructions for pica-safe behavior, and designated areas for parents to document whether locations were safe, or the unsafe items they removed or secured (see Online Supporting Information for home version). The checklists were adapted from descriptions of checklists and pica-safe environments in the literature (e.g., Williams et al., 2009; Williams & McAdam, 2012). After reading the checklist directions, parents were asked to make a transition with their child to the new location with the checklist.

Extension

Parents moved to the extension phase after stable performance ≥ 80% for at least three consecutive sessions. Extension sessions were conducted in new areas (e.g., hospital courtyard for Nancy) and incorporated new pica items (e.g., paper and dried rice noodles that resembled plastic for Margo).

Home Checklists

As an ancillary measure, parents were asked to complete the checklists at home daily, for at least 5–7 days. Checklists were modified to include locations in the home their child would occupy. The purpose of this phase was to bolster overall efforts toward treating the participant’s pica by extending the protocol to the home.

Social Validity

Following training, parents were asked an open-ended question for their thoughts about using the pica safety checklist (i.e., “What are your thoughts about using the checklist?”). A generic response (e.g., “I liked it”) was followed up with a clarifying prompt (e.g., “Can you tell me more about that?”). The first author took notes on their responses and read back to parents to verify that statements were correctly recorded.

Results

Pretreatment Assessments

At intake, Nancy’s parent reported six targets of pica along with an ambiguous “random items.” Results of Pica and Related Behavior Inventory yielded 15 substances and clarified that only 4 were swallowed (i.e., pica) with the remainder associated with other oral behavior problems (e.g., lick, bite/chew, mouth/suck). Brian’s parent reported 10 targets and “whatever” at intake. The Pica and Related Behavior Inventory generated a total of 36 substances, 19 of which were routinely swallowed. At intake, six pica targets were reported for Margo. Pica and Related Behavior Inventory results increased her list to 12 swallowed items from a revised total of 14 substances. Finally, results of all participants’ functional analysis suggested their pica was maintained by automatic reinforcement as it was observed in all conditions, including alone or no-interaction conditions. Margo’s pica was most prevalent in the alone condition, corresponding to reports of covert pica.

Treatment Evaluation

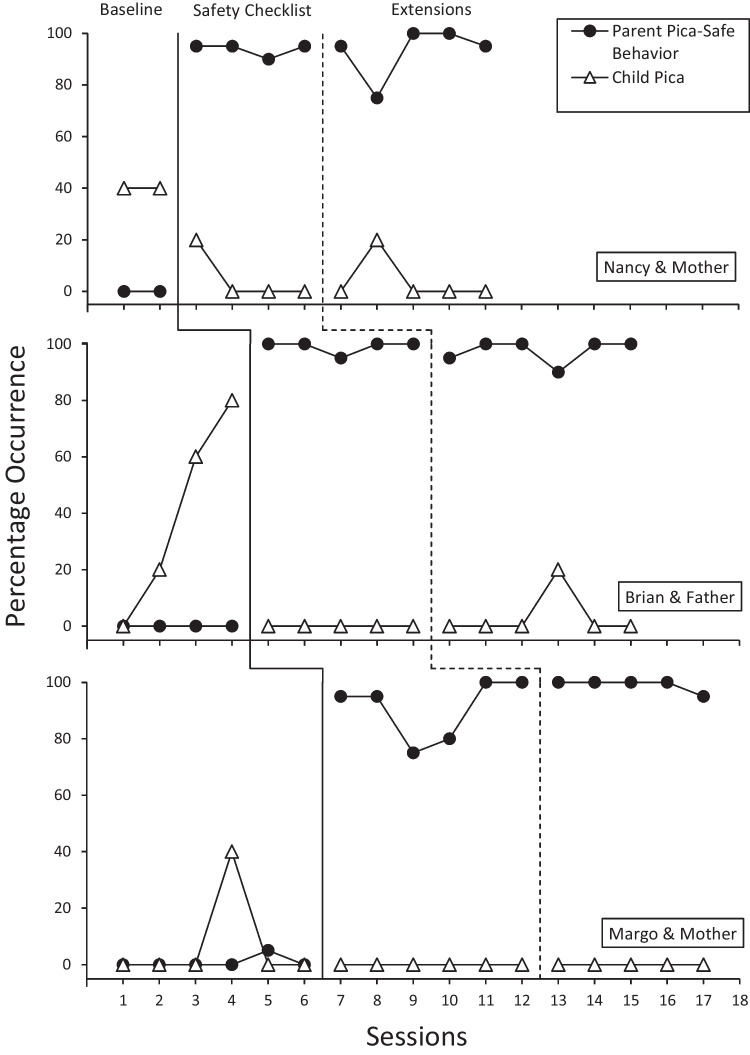

Results of the treatment evaluation are presented in Fig. 1. Nancy’s mother did not display any pica-safe behavior during baseline. Nancy displayed pica in 40% of trials in each baseline session. In addition, Nancy was observed to walk far ahead of her mother during baseline transitions. With use of the safety checklist, her mother’s pica-safe behavior improved to 90%–95%, and Nancy’s pica diminished to only one attempt across four sessions. Her mother’s most erred-upon component was blocking Nancy from entering the room before her initial scan was complete.

Fig. 1.

Results of a Safety Checklist on Parent Pica-Safe Behavior and Their Child’s Pica

Across four baseline sessions, Brian’s father did not display any pica-safe behavior, and pica increased from 0% to 80% of trials. It was noted the Brian often lunged ahead of father into the room to access targets, despite having his hand held on most occasions. With the checklist, father’s pica-safe behavior increased to 90%–100%, and Brian’s pica diminished to zero across five sessions.

Margo’s mother correctly removed items during one trial of six baseline sessions (5%). Margo displayed few attempts at pica during baseline (40%, one session). During six treatment sessions with the checklist, her mother’s procedural integrity ranged from 75%–100%, and no pica or attempts were observed. Low performance was attributed to mother occasionally allowing Margo to enter a room before her.

Treatment Extensions

All parent–child dyads completed extension sessions with new materials and in new locations. Across five extension sessions, Nancy’s mother maintained 75%–100% integrity, and one blocked pica attempt was observed in one trial. Likewise, Brian’s father’s integrity ranged from 90% to 100% in six extension sessions, and Brian only attempted pica in one trial. Finally, during Margo and her mother’s five extension sessions, parent integrity ranged from 95% to 100% and no pica or attempts were observed.

Overall, training time was minimal, with a maximum of 5 min per session, and embedded within the participants’ therapy sessions. Nancy and her mother completed baseline through extension across eight appointments. Brian and his father finished in seven appointments, and Margo and her mother completed all training within six appointments.

Home Checklists

Home checklists were analyzed for recurring safety concerns, with respect to specific items and areas of the home. Results were reviewed with the parents to troubleshoot alternative storage and safety measures as necessary. Nancy’s home checklists revealed that the kitchen (4/6 days) and bathroom (3/6 days) often contained targets of her pica. Items such as cardboard and plastic bottles where then incorporated into her treatment for pica by teaching her to recycle the items as a failsafe. Brian’s home required daily room clears in the kitchen (6/6 days), bathroom (4/6 days), and bedroom (4/6) days. The most common items were hair ties, rubber bands, and coins. The family then found alternative storage for those items. Finally, Margo’s home required few room clears. The most common concern was that another family member left the bathroom door open (2/5 days), and this left toilet paper tubes and toothpaste vulnerable to pica.

Social Validity

Nancy’s mother discussed that she has relaxed more because of using the checklist at home. To her, it previously felt overwhelming because everything seemed like a target for pica. She noted that her daughter targets fewer items than originally thought. The family can more readily remove the targets and not worry as much if she needs to leave the area for a bit to prepare a meal, for example. Brian’s father reported that using the inventory and checklist helped them notice that there were fewer items that Brian routinely targeted, which made prevention feel more manageable. Brian’s father noted that they found alternative storage for some routine targets (e.g., soaps and latex gloves), and were working on improving family/sibling adhering to cleaning up their items (e.g., hair ties). Overall, the family noted that it changed their mindset to be more proactive with prevention. Margo’s mother noted the checklist prompted behavior that was similar to what she already did in her home; but had not done in different settings. She was eager for school and therapy staff to use the checklist because many instances of covert pica were now occurring away from her home.

Discussion

The current study demonstrated the effects of parents using a checklist to create pica-safe areas for their children. Although this was a highly successful treatment component, it is important to mention that this should not be used as a sole treatment, but in conjunction with a functional analysis and behavioral treatment. During baseline, no parent removed or prevented their child from accessing targets of pica, and this was associated with numerous instances of pica across all child participants. Following use of the checklist, all parents immediately increased their pica-safe behavior, and this extended to additional pica targets and locations. In addition, pica reduced to near zero for all child participants, and parents made improvements at home between appointments.

Because of the danger associated with pica, treatments should aim for reductions to zero occurrences (Williams & McAdam, 2012). Research suggests that pica is most often maintained by automatic reinforcement, which can make it more difficult to treat (Hagopian et al., 2011). Of note, automatically maintained problem behavior is also associated with increased caregiver stress (Kurtz et al., 2021). Teaching caregivers to create pica-safe areas in their home could help reduce stress to some extent by potentially reducing the need for continuous monitoring, which may be exhausting. In addition, designating some areas of the home as pica-safe may focus caregiver treatment efforts to a narrower range of times and places to improve success (e.g., Sturmey & Williams, 2016). Parents in the current report were taught to create pica-safe areas in real-time while making a transition to new locations with their child. This is likely more difficult, and albeit more stressful than completing a pica sweep when the child is not there. Nonetheless, parents quickly adapted, and most held their child’s hand; a behavior that was not observed in baseline. Related, practitioners might consider increasing caregiver mastery criteria for this protocol to above 90%, due to the risks associated with pica.

A limitation of this report is that training primarily occurred in an outpatient clinic for two participants. Although parent-collected data from homework assignments led to reported positive changes in the home, we were unable to calculate interobserver agreement and thus reported as ancillary. To date, few published studies have demonstrated effective parent-implemented treatments for pica in the home. We hope results of this report encourage further work into training parents to manage pica in their homes and other natural settings.

Implications for Practice

The procedures in this report can help parents keep their child safe by reducing opportunities for pica.

Providers can use this checklist to minimize pica risk during their appointments.

The safety checklist can be easily modified to use in many settings

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Matthew D. Bowman and Diksha Bali for assistance with data collection.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this report are available upon request.

Declarations

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in this report were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional review board and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent to Participate/for Publication

Informed consent was obtained for all individual participants included in the report.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cordon IM, Lutzker JR, Bigelow KM, Doctor RM. Evaluating Spanish protocols for teaching bonding, home safety, and health care skills to a mother reported for child abuse. Journal of Behavior Therapy & Experimental Psychiatry. 1998;29(1):41–54. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7916(97)00037-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields VL, Soke GN, Reynolds A, Tian LH, Wiggins L, Maenner M, DiGiuseppe C, Kral TVE, Hightshoe K, Schieve LA. Pica, autism, and other disabilities. Pediatrics. 2021;147(2):e20200462. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher WW, Piazza CC, Bowman LG, Kurtz PF, Sherer MR, Lachman SR. A preliminary evaluation of empirically derived consequences for the treatment of pica. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1994;27(3):447–457. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1994.27-447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagopian LP, Rooker GW, Rolider NU. Identifying empirically supported treatments for pica in individuals with intellectual disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2011;32(6):2114–2120. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2011.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz PF, Strohmeier CW, Becraft JL, Chin MD. Collateral effects of behavioral treatment for problem behavior on caregiver stress. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders. 2021;51(8):2852–2865. doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04694-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNaughten B, Bourke T, Thompson A. Fifteen-minute consultation: The child with pica. Archives of Disease in Childhood-Education & Practice. 2017;102(5):226–229. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2016-312121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metchikian KL, Mink JM, Bigelow KM, Lutzker JR, Doctor RM. Reducing home safety hazards in the homes of parents reported for neglect. Child & Family Behavior Therapy. 1999;21(3):23–34. doi: 10.1300/J019v21n03_02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza CC, Fisher WW, Hanley GP, LeBlanc LA, Worsdell AS, Lindauer SE, Keeney KM. Treatment of pica through multiple analyses of its reinforcing functions. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1998;31(2):165–189. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1998.31-165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturmey, P., & Williams, D. E. (2016). Pica in individuals with developmental disabilities. Berlin: Springer.

- Tertinger DA, Greene BF, Lutzker JR. Home safety: Development and validation of one component of an ecobehavioral treatment program for abused and neglected children. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1984;17(2):159–174. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1984.17-159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, B. R. (2022). Pica and related behavior inventory (PRI).

- Williams DE, McAdam D. Assessment, behavioral treatment, and prevention of pica: Clinical guidelines and recommendations for practitioners. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2012;33(6):2050–2057. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson PJ, Workman EA. The non-concurrent multiple baseline across-individuals design: An extension of the traditional multiple baseline design. Journal of Behavior Therapy & Experimental Psychiatry. 1981;12(3):257–259. doi: 10.1016/0005-7916(81)90055-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DE, Kirkpatrick-Sanchez S, Enzinna C, Dunn J, Borden-Karasack D. The clinical management and prevention of pica: A retrospective follow-up of 41 individuals with intellectual disabilities and pica. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities. 2009;22(2):210–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3148.2008.00490.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this report are available upon request.