Abstract

Mycelia and mushrooms are able to bioaccumulate minerals. Lithium is the active principle of drugs used in the treatment of psychiatric diseases. However, a dietary source of Li can reduce the side effects of these drugs. Thus, the objective of this study was to evaluate the bioavailability of Li-enriched mushroom of Pleurotus djamor in pigs and the effects of this element on oxidative stress in the animal tissues. Pigs 28–30 days-old were fed with diets containing or not Li for five days. Levels of serum cortisol were related to the Li dosage from diet. Li-enriched mushrooms were more bioavailable source of Li to the body than Li2CO3. These mushrooms also improved the effects of oxidative enzymes and showed less oxidative damage than Li2CO3. These results demonstrate the potential to use Li-enriched P. djamor as a source of Li that is more bioavailable and present protective effects against oxidative stress.

Keywords: Functional food, Oxidative stress, Brain, Liver, Blood

Introduction

The fungi are capable of bioaccumulating minerals in the mycelia and mushrooms, which enable them to supply the deficiency of these nutrients (da Silva et al. 2012; Vieira et al. 2013; Hu et al. 2020). In addition to being a highly healthy food source, edible mushrooms may be managed to make some minerals more bioavailable, as for example the selenium (Hu et al. 2020) and more bioaccessible, as demonstrated to lithium (de Assunção et al. 2012).

The mycelial growth and mushrooms production of Pleurotus spp. and Lentinus crinitus in culture medium or substrate containing different sources of Lithium (Li), such as acetate, sulfate, chloride, hydroxide, and carbonate has been observed in some studies (de Assunção et al. 2012; Vieira et al. 2013; Faria et al. 2019; Lopes et al. 2022). The bioaccumulation of Li in the mushroom was also evidenced in these studies. However, it is not known whether this element undergoes any chemical transformation or if it is incorporated into some organic molecule during fungal metabolism. De Assunção et al. (2012) demonstrated in vitro that the Li-enriched mushrooms of Pleurotus ostreatus were more accessible than the same element in the psychiatric medication containing lithium carbonate. However, the in vitro study does not use all the physiological factors involved in the absorption and use of nutrients, and in vivo studies are necessary for the analysis of all these factors.

Although Li is not yet considered an essential micronutrient for living beings, it performs a number of functions in the body. This element is also used as drugs in the treatment of psychiatric diseases, especially Li salts. The lithium carbonate (Li2CO3), lithium chloride (LiCl), lithium citrate (Li3C6H5O7), lithium sulfate (Li2SO4), lithium orate (LiC5H3N2O4 H2O), and lithium aspartate (C4H5Li2NO4) are the chemical compounds most commonly used of these drugs composition (Oruch et al. 2014). However, the administration of these salts, mainly in the form of carbonate, in human can generate side effects, such as nausea, diarrhea, urination, excessive thirst, hand tremor, weight gain, cognitive impairment, sexual and thyroid dysfunctions, and dermatological and kidney problems (Gitlin 2016). According to these authors, these side effects are the main cause of low adherence of patients to Li treatment.

Li toxicity depends on the animal species and the time of exposure to this element (Shahzad et al. 2017). The serum therapeutic concentration of Li in human ranges from 0.5 to 1.0 mmol L−1. Mild and severe symptoms of Li toxicity are observed in the range from 1.8 to 2.5 mmol L−1 and higher than 2.5 mmol L−1, respectively (Oruch et al. 2014; Won and Kim 2017).

The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and some authors recommend a daily dose of approximately 1000 µg of Li for an adult of 70 kg (Schrauzer 2002; Szklarska and Rzymski 2019). Among these health benefits, Li is known for the ability to stimulate the production of neural stem cells (Zhang et al. 2019), protect against oxidative stress, stimulate the immune system, produce a calming effect, present a neuroprotective effect (Szklarska and Rzymski 2019), besides its potential to prevent and treat some types of cancer (Ge and Jakobsson 2019). Studies in different cities have demonstrated that increased Li levels (12 to 160 μg L−1) in drinking water reduce the occurrence of homicide, suicide and neurodegenerative diseases (Kessing et al. 2017; McGrath and Berk 2017; Barjasteh-Askari et al. 2020).

Thus, the objective of this study was to evaluate the bioavailability of Li-enriched mushroom of Pleurotus djamor in pigs and the effects of this element on oxidative stress in the animal tissues (blood, brain, liver and kidney).

Materials and methods

Production of Li-enriched mushrooms

Pleurotus djamor (strain PLO 13) used in the study belongs to the collection of fungi of the Laboratory of Mycorrhizal Associations/Department of Microbiology/Institute of Biotechnology Applied to Agriculture and Livestock—BIOAGRO/Universidade Federal de Viçosa – UFV. The P. djamor PLO 13 was grown in Petri dishes containing 20 mL of potato-dextrose-agar culture medium at 25 ± 1 °C. After seven days, ¼ of the medium growth totally colonized by the fungus was transferred to each 280 mL pot containing 130 g of cooked and autoclaved sorghum grain.

The substrate used for the production of the mushrooms was a mixture of coffee husk and sugarcane bagasse (9:1, w/w). The coffee husk was cooked for 2 h and centrifuged at 1500 × g for 1 min. The sugar cane bagasse was immersed in a 2% calcium hydroxide solution (w:v) for 12 h and centrifuged at 1500 × g for 1 min. Next, 1 kg of this mixture was placed in a polypropylene bag and autoclaved for 1 h at 121 °C. Then, P. djamor PLO 13 was inoculated into the substrate with 50 mL lithium chloride, at the concentration of 40 g L−1. After about 25 days, the mushrooms were harvested, dried and grounded.

Lithium content of mushrooms

Mushroom powder (0.1 g) was submitted to digestion with a mixture of nitric acid and perchloric acid (3:1, v:v) at 200 °C for 2 h (Tedesco et al. 1995; De Assunção et al. 2012). After digestion and cooling to 25 °C, 2 mL of deionized water was added to the digestion tubes. The content of Li was determined using an atomic emission in a flame spectrophotometer (AA-6701F, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) using a lithium hollow cathode lamp with a current of 5 mA. Operational parameters of the equipment were adjusted as recommended by the manufacturer: wavelength of 670.8 nm, slit width of 1.4 nm, relative noise of 1.0, sensitivity of 0.035 (mg L−1), sensitivity check 2.0 (mg L−1), and flame of nitrous oxide-acetylene. The standard curve was performed at lithium concentrations 0.00; 0.09; 0.36; 0.72; 1.44; 1.80; 2.88; 3.60; and 9.00 mg L−1. The concentration of Li in the dry mass was calculated by the equation: Li (µg g−1) = [M] x DF/MD × 1000 (De Assunção et al. 2012). In this equation, [M] = mineral concentration in mg L−1; DF = dilution factor = 0.025, and MD = mushroom dry mass.

Pig tolerance to lithium carbonate

The animal assay was carried out in partnership with the pig farm of the Department of Animal Science at UFV. All methods involving the handling of pigs followed the ethical principles of animal research from National Council for the Control of Animal Experimentation (CONCEA, Law number 11,794, of October 8, 2008) and Commission of Ethics in the Use of Animal Production of the Universidade Federal de Viçosa (Protocol No. 02/2021).

To evaluate the maximum dosage of Li and tolerance to lithium carbonate (Li2CO3), it was used in 24 animals of 28-days-old female pigs (Sus Domesticus, AGPIC 415 × Camborough; Agroceres PIC, Patos de Minas, MG, Brazil). A group of three animals received the following oral doses of lithium carbonate daily, during five days: 0.034, 0.068, 0.136, 0.205, 0.272, 0.350, 0.650, and 0.950 g. The lithium carbonate was weighed and encapsulated in gelatin capsules nº 00. All animals received water and food ad libidum and were distributed in a completely randomized design. The animals were observed after oral administration of the capsule to ensure its ingestion. On the sixth day, 10 mL of blood was collected by puncture of the orbital sinus for lithium quantification.

Lithium bioavailability and oxidative stress

The Li bioavailability and oxidative stress were analyzed in 28 animals (28-day-old female pigs, Sus domesticus, AGPIC 415 × Camborough; Agroceres PIC, Patos de Minas, MG, Brazil). These swine were distributed in 7 pens, with 4 animals per pen, in a completely randomized design. The temperature of the pen was maintained within the thermoneutral zone during the experimental times. The pigs had free access to feed and water throughout the five experimental times.

To verify the effect of lithium carbonate and Li-enriched mushroom in its different forms and/or dosages (therapeutic or recommended), the following treatments were performed (Table 1).

Table 1.

Source and content of lithium provided for each pig

| Diets | Lithium dosage (mg/day)* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acronyms | Description | Recommended | Therapeutic | Overdose |

| Control | No lithium | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| LiT | Li2CO3 (300 mg) | 0 | 56 | 0 |

| M + LiT | Li-enriched mushroom flour (122 g) | 0 | 56 | 0 |

| M | Non-enriched mushroom flour (122 g) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| LiR | Li2CO3 (5.7 mg) | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| M + LiR | Li-enriched mushroom flour (2.2 g) | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| LiS | Li2CO3 (600 mg) | 0 | 0 | 113 |

The dosage of Li was administered dividing into 3 times a day (Table 1). This process was repeated during five experimental days. The treatments, control and non-enriched mushroom also received empty capsules 3 times a day, so that all animals could be under the same stress conditions.

In order to verify how the Li was absorbed by the pigs, 4 mL of blood was collected daily, at 8 am. These samples were submitted to laboratory analysis for serum Li quantification.

At the end of the experimental times (sixth day), 12 mL of blood was taken from each animal. Then, the animals were electrically stunned, and exsanguination was performed for sample collection of brain, liver and kidney tissues.

Quantification of Li

Brain, liver, and kidney tissues were collected, and red blood cells were obtained from blood samples taken on the last day of the experiment. The tissue samples were dehydrated at 70 °C until constant weight, ground, and homogenized. Soon after, 300 mg of each tissue was submitted to nitroperchloric digestion and quantification of lithium (Tedesco et al. 1995; De Assunção et al. 2012). The red blood cells were centrifuged and separated from the serum. Then, 4 mL of 0.9% NaCl was added to each tube and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 15 min. The supernatant was discarded. This washing process was repeated fivefold. The red blood cell samples were dehydrated at 70 °C until constant weight and submitted to the same digestion process of the other tissues.

Urine samples were taken from the bladder of the animals immediately after slaughter and stored at – 20 °C. For the quantification of lithium, 5 mL of urine was diluted in 15 mL of distilled water and subsequently filtered using filter paper. The samples were subjected to quantification by atomic emission in a flame spectrophotometer, using the adapted methodology described by Dol et al. (1992). The blood serum samples were subjected to a colorimetric assay and quantified in a flame photometer.

Serum cortisol levels

The serum cortisol was subjected to a chemiluminescence test, as described by Tellez et al. (2006).

Oxidizing activity and oxidative stress markers in tissues

To prepare the samples, 100 mg of each tissue (brain, liver and kidney) was thawed and homogenized in phosphate buffer (0.2 mol L−1) in ethylene diaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA, 1 mmol L−1, pH 7.4). The homogenates were centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 10 min, at 4 °C. The supernatants were used for analysis of the enzymatic activity.

The activity of superoxide dismutase (SOD) was determined by reduction in superoxide (O−2) and hydrogen peroxide (Dieterich et al. 2000). Catalase activity (CAT) was determined according to Aebi (1984) using hydrogen peroxide (20 mmol L−1) as enzymatic substrate. The activity of glutathione S-transferase (GST) was measured using the method of Habig et al. (1974). The extent of lipid peroxidation (OLP) was measured using malondialdehyde (MDA), which is the main product of lipid peroxidation (Buege and Aust 1978).

Statistical analysis

The data were submitted to the Shapiro–Wilk test, analysis of variance, Fisher test for multiple comparisons in the Minitab software (version 9.0), and regression analysis in the R program.

Results

The Li content in fungal biomass was 464 μg per gram of dry mushrooms P. djamor PLO 13. This Li bioaccumulation was greater than the bioaccumulation of this element observed in other mushrooms. Thus, this mushroom may be a viable alternative for providing Li doses in the development of therapeutic drugs for humans.

Pig tolerance to lithium carbonate concentration

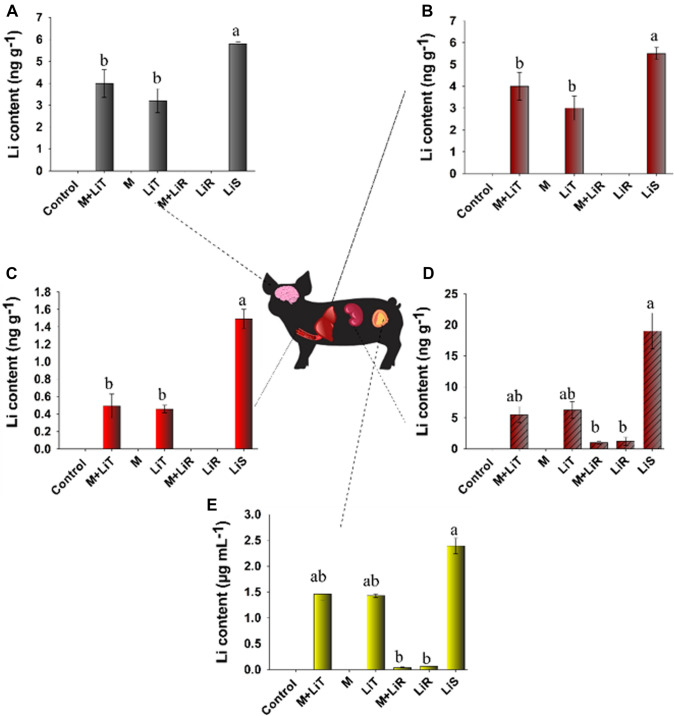

This study shows the first information regarding the tolerance of pigs to lithium salt. Serum lithium concentration in pigs did not exceed 0.25 mmol L−1 and there was no difference at Li2CO3 dosages below 0.136 (Fig. 1A). Increased lithemia was observed for the dosage above 0.205 g of Li2CO3. At the dosage of 0.650 g Li2CO3, the animals had mild symptoms of intoxication, such as fine tremors and diarrhea. The serum concentration of Li in these animals was 2.90 mmol L−1.

Fig. 1.

Serum lithium concentration (A) and lithium kinetics absorption (B) in the blood for 6 days in pigs treated with different doses of Li2CO3 and Li-enriched mushroom flour during five days (Table 1). In figure B, animals with diet of (▼) 300 mg Li2CO3, (●) 122 g of Li-enriched mushroom (M + LiT), and (■) 600 mg of Li2CO3 per day

In vivo lithium bioavailability and oxidative stress

In control and non-enriched mushroom, the Li concentrations in the serum of the pigs were below the limit of detection of (0.10 mmol L−1). While, the lithium treatments had an increase serum Li over the days and equilibrium was observed after the third day (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, the Li bioavailability in diets with Li-enriched mushroom flour was higher than in diets with the 300 mg Li2CO3 (Fig. 1B).

Li content in the animal tissues

The Li level in the control animals and treated with non-enriched mushroom was levels below the detection limit in the animal tissues analyzed. This result was expected, since Li was not added in the either to the flour or the growth substrate of the mushroom.

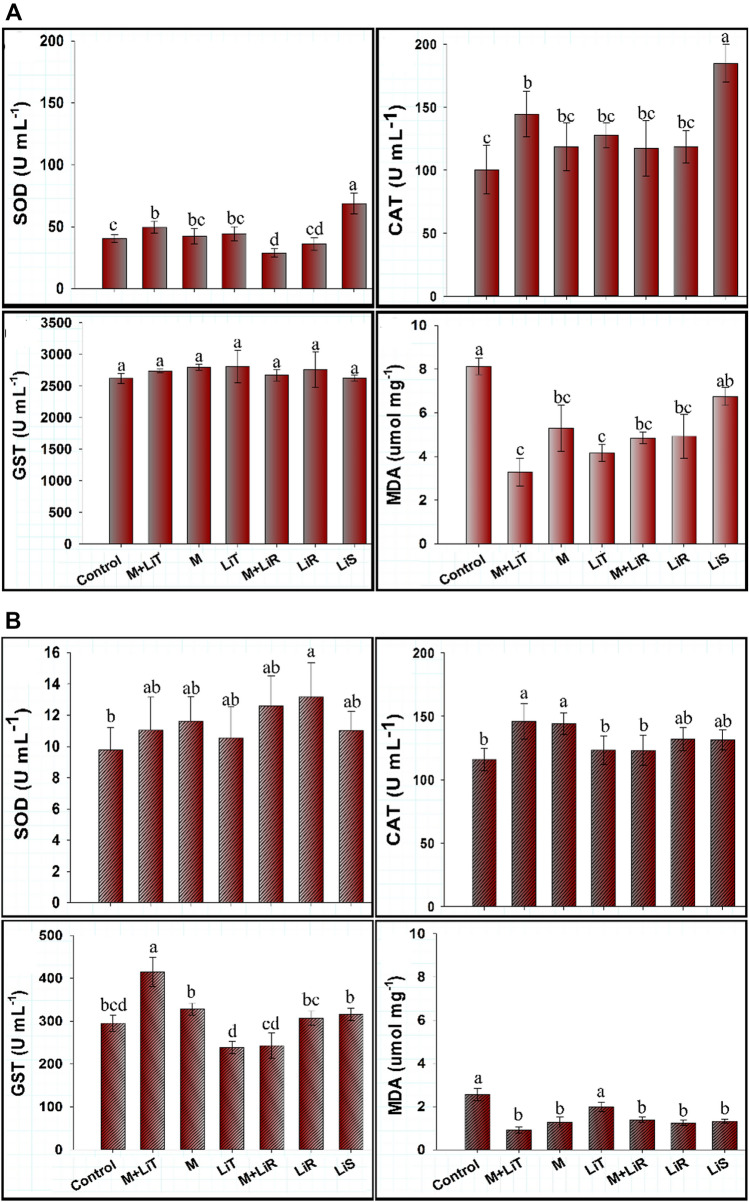

Li was detected in the brain (Fig. 2a), liver (Fig. 2b), erythrocytes (Fig. 2c), kidney (Fig. 2d) and urine (Fig. 2e) of animals treated with Li-enriched mushroom (M + LiT) and Li2CO3 (LiT). Both treatments had the recommended daily dose of 56 mg of Li. Serum concentrations of this element were around 1.3, 1.0 and 2.3 mmol L−1 for the treatments M + LiT, LiT, and LiS, respectively (Fig. 1A; Table 1). In the urine, in the same treatments, the values were approximately 1.5 for the first two and 2.4 mmol L−1 for the last one dosages (Fig. 2e). There was no difference between these two treatments, which reveals that Li obtained from mushroom presents the same accumulation in the tissues as LiT. The highest concentration of Li (1.22 mmol L−1) was found in blood serum when pigs were fed with M + LiT. Among the tissues, the kidney accumulated the highest concentration, about 6 ng of Li per gram of dry tissue. For animals fed with LiS, the serum had the highest concentration of Li, followed by the kidney, liver, brain and erythrocytes (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Quantification of Li in the brain (a), liver (b), erythrocytes (c), kidney (d) and urine (e) of animals treated with diets without (control and M) or with lithium (LiT, M + LiT, LiR, M + LiR, and LiS, Table 1). Means that do not share the same letter are statistically different by Fisher’s test (p < 0.05)

Serum cortisol levels

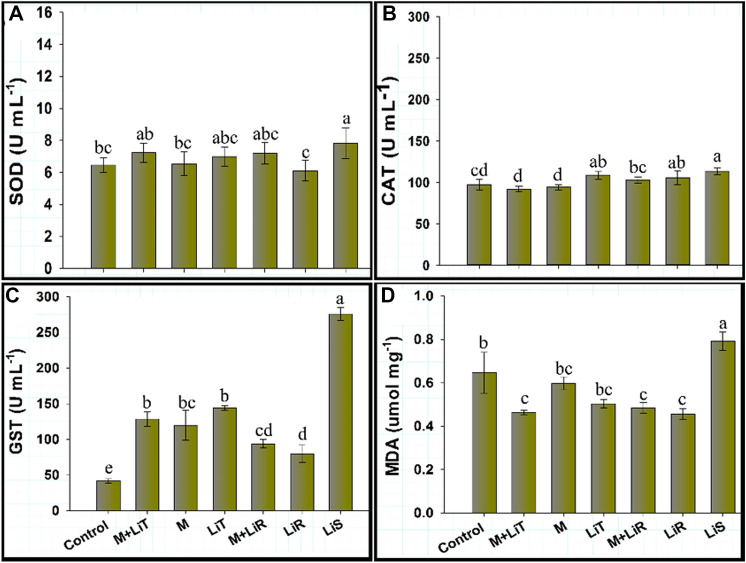

Pigs of the LiS diet in the dosages of 650 mg Li2CO3 and in the serum concentration of 2.3 mmol L−1 of Li, had the highest serum cortisol values (Fig. 3A). These animals had clear symptoms of Li poisoning, such as tremors and diarrhea. However, the second highest dose of cortisol was observed in pigs that did not receive any Li or mushroom. Furthermore, the lowest serum cortisol levels were identified for the animals that received LiT (56 mg of Li) or M + LiR (2.2 g of enriched mushroom with 1 mg of Li). Other treatments had no differences (p > 0.05) in serum cortisol levels (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

The serum cortisol level (figure A) and activities (figure B) of Superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), glutathione S-transferase (GST), and malondialdehyde antioxidants (MDA) in the brain of pigs administered with different diets of Li (Table 1). Means that do not share the same letter are statistically different by Fisher’s test (p < 0.05)

In the LiT and M + LiT diets that contained the lowest Li dosages, this element seems to have a negative effect on cortisol production. However, when the Li provided diet with mushroom flour in the recommended daily dosage (1 mg of Li per day), even far below the dosage of the LiT treatment (56 mg of Li per day), tranquilizing effects in pigs are observed.

Enzymatic antioxidants and oxidative damage markers

Brain

The highest levels of SOD in the brain were observed in treatments that received Li, regardless of the dosage or diet provided, Li2CO3 or Li-enriched mushroom (Fig. 3B). Animals that did not receive Li had lower levels of this enzyme. Thus, this mineral can stimulate SOD activity. However, lower levels of CAT were observed in the diets with enriched mushroom in the therapeutic and recommended dosage (Fig. 3B). The treatments with enriched mushroom seem to have a lower effect on CAT when compared to the other forms of Li provided, mainly at higher dosage, as is the case of the LiS diet (Fig. 3B).

For GST, there was difference between the LiS diet and the others diets, which reveal an increase in about 4 times in its activity (Fig. 3B).

MDA levels are higher in the animals with Control and LiS diets (Fig. 3B), which reveal that these groups suffered the most oxidative damage and that, at therapeutic dosage (M + LiT and LiT) and recommended daily dosage (M + LiR and LiR).

Liver

The liver enzymes SOD and CAT have similar behavior between diets (Fig. 4A). SOD presented the highest activity in the LiS and M + LiT diets, although the later did not differ from M and LiT (p > 0.05). CAT also had the highest levels for LiS and M + LiT, in which the later differed only from the control (p < 0.05). Liver GST had no difference between diets (p > 0.05).

Fig. 4.

Activities of Superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), glutathione S-transferase (GST), and malondialdehyde antioxidants (MDA) in the liver (figure A) and kidney (figure B) of pigs administered with different diets of Li (Table 1). Means that do not share the same letter are statistically different by Fisher’s test (p < 0.05)

The diets that exhibited greater damage related to lipid peroxidation, and consequently higher values for MDA are in the Control, M, and LiS (Fig. 4A). The lowest values of MDA were quantified in M + LiT and LiT. Thus, regardless of the form (Li-enriched mushroom or Li2CO3), this dosage of Li can cause less damage to the liver than other treatments.

Kidney

The lowest value of renal SOD activity was obtained for the control, but this differed only from the LiR diet (p < 0.05; Fig. 4B). The highest of CAT activity was observed for M + LiT and M diets. These diets did not differ (p < 0.05) in the CAT activity from LiR and LiS diets (Fig. 4B). The GST activity in M + LiT diet was difference (p < 0.05) from all other treatments, including LiT, which received the same dosage of Li but in the form of Li2CO3. Furthermore, the highest GST activity and the lowest value for lipid peroxidation were observed in the M + LiT diet (Fig. 4B). The control and LiT were the diets that suffered the greatest oxidative damage (Fig. 4B).

Serum

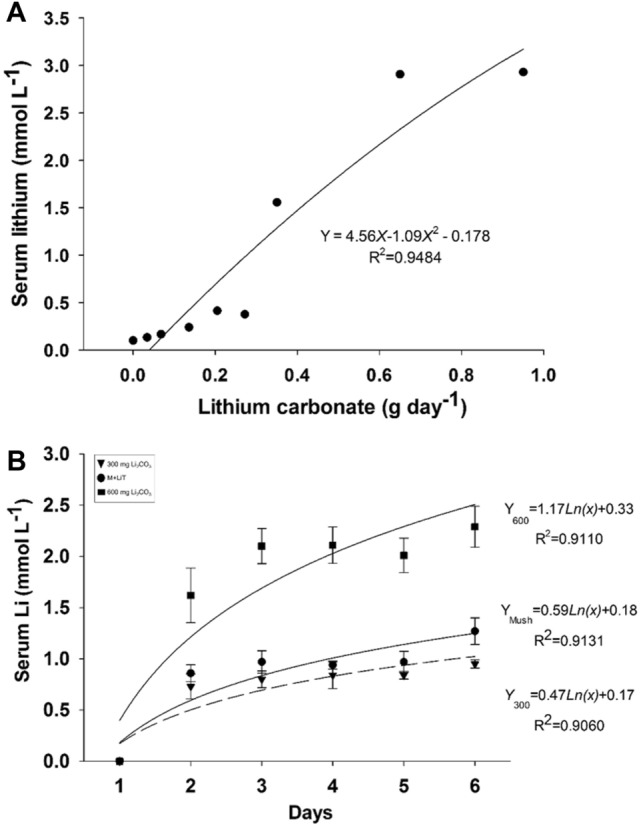

The quantifications of antioxidant enzymes in blood serum did not differ between diets (p > 0.05), except for GST, in which the lowest and highest values of their activity were those of the control and LiS, respectively, which differentiated them from the other treatments (Fig. 5). Apparently, the administration of Li at dosages from the therapeutic level stimulates the activity of these enzymes.

Fig. 5.

Activities of Superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), glutathione S-transferase (GST), and malondialdehyde antioxidants (MDA) in the blood serum of pigs administered with different sources of Li (Table 1). a Superoxide dismutase activity; b Catalase activity; c Glutathione S-transferase activity and d levels of malondialdehyde. Means that do not share the same letter are statistically different by Fisher’s test (p < 0.05)

The analysis of the stress markers demonstrates that the lowest levels of MDA were generated in the M + LiT diet. This value did not differ from the levels of MDA observed in the other diets that received Li2CO3 and Li-enriched mushroom, except for the LiS. In this diet with overdose of Li was observed the highest levels of MDA (Fig. 5).

Discussion

Our results show that Pleurotus djamor is a very good accumulator and of Li and tolerate high doses of Li. Pleurotus ostreatus grown in coffee husk bioaccumulated about 200 μg (de Assunção et al. 2012) and 37.5 μg (Vieira et al. 2013) of lithium per gram of dry mushroom. Lopes et al. (2022) also observed a maximum accumulation of 135 and 3 μg g − 1 of Li in P. ostreatus PLO 02 cultivated in a mixture of coffee husk and sugarcane bagasse (9:1, w/w). Furthermore, the solubility and availability of Li in the P. djamor PLO 13 mushrooms can be controlled through its association with organic compounds as observed for other ions, which can be digested and released slowly during digestion, which reduces the risk of intoxication and/or other collaterals effects (Scheid et al. 2020).

So far no published studies on the tolerance of pigs (Fig. 1A) to the Li or lithium salts. The same symptoms of intoxication found in our study have been observed in humans with daily use of Li2CO3 and serum Li concentration from 1.8 to 2.5 mmol L−1 (Oruch et al. 2014; Won and Kim 2017). At the highest dosage of 0.950 g of Li2CO3 per day, the Li concentration in the serum was 2.91 mmol L−1 and the animals had severe symptoms of intoxication, such as muscle weakness, shaky limbs, loss of appetite, and diarrhea (Fig. 1A). The intoxication symptoms are also observed in humans with litemia above 2.5 mmol L−1 (Oruch et al. 2014; Won and Kim 2017). Lithium toxicity can induce lipid peroxidation in neurons, which leads to serious disorders (Efendiev and Kerimov 1994; Yao et al. 1999; Yousefsani et al. 2020). The Li alters the membrane potential in the mitochondria and increases the production of reactive oxygen species, which damages various cellular structures (Yousefsani et al. 2020).

The behavior of lithium in the porcine organism is similar to that of humans, and its toxicity depends on the chemical species and the time of exposure to Li (Shahzad et al. 2017). Although the serum Li values for toxicity in pigs are close to those of humans, we must take into account the dosage used and the weight of the animals. The animals of this study had body mass of approximately 7 kg. An adult individual of 70 kg who makes therapeutic use of lithium salt consumes 600 to 1200 mg of Li2CO3 daily (Shahzad et al. 2017). Thus, the therapeutic dosage of Li in pigs (7 kg body mass) is tenfold lower than this dosage for human adult (about 60 to 120 mg of Li2CO3). However, we can observe that 10 times higher doses were necessary to reach serum therapeutic and overdose levels similar to those of humans, which may indicate that these animals are more tolerant to high doses of Li when compared to humans.

So far, this is the first in vivo experiment that demonstrates that Li-enriched mushrooms are a source more bioavailable than Li2CO3 and, in addition to being considered a healthy food, it can be used as a source of Li. Besides, it can be a functional food and provide pharmacological benefits. Bioavailability is the proportion of a nutrient in a food that is available to the body, reaches the bloodstream, and can be used in bodily functions (Uribe-Wandurraga et al. 2020). There are in vitro studies demonstrating that the Li present in the enriched mushroom is more bioaccessible to the organism when compared to Li2CO3 (de Assunção et al. 2012). In the in vitro study by Scheid et al. (2020), the mycelium of different fungal species enriched with Li had higher bioaccessibility than the control.

Lithium salts are almost completely absorbed in the small intestine and distributed in the body by the fluids (Wen et al. 2019). In our results, the lithium was accumulated in higher concentration in kidneys than in other investigated tissues (Fig. 2). Results similar to our data were also observed in rats with LiCl diets (Garcíaa et al. 1999). In contrast, although the distribution of this element in the organs is uneven, the brain and kidneys accumulate most of the Li than other organs (Hillert et al. 2012). The differences in Li concentration among the tissues can be due to the characteristics of the plasma membrane of the cells in each tissue, which can affect the transport of that ion (Garcíaa et al. 1999). Li positively helps in the oxidative defense of the organism. However, dosages of Li above the therapeutic level or its non-administration (control) have a negative effect. Furthermore, it is worth mentioning that only the renal tissue had quantification of Li in the M + LiR and LiR diets with the recommended dosage of Li per day.

The present data are corroborated with the findings of other authors (Iwai et al. 2021). These authors observed that Li concentrations in the urine well reflected the serum ion concentration in human. Human and pigs’ serum and urine had a positive correlation between serum Li and the Li excreted in the urine. Orally, Li is absorbed and excreted in the urine and has a half-life of 12 h (Wen et al. 2019).

Cholesterol is a hormone synthesized by the adrenal glands and is one of the most used biomarkers to assess stress in pigs (Martínez-Miró et al. 2016). At high doses, Li stimulates the production of cortisol and at lower doses; Li seems to have a negative effect on the production of this hormone (Fig. 3A). The increase in the cortisol production in humans with bipolar disorder was related to the increase Li dosage consumed (Bschor et al. 2002). Furthermore, the Li in drinking water (at levels ranging from 12 to 160 μg per liter of water) reduces homicide, suicide and related diseases (Knudsen et al. 2017; Barjasteh-Askari et al. 2020). Human affected with bipolar disorder, who were using Li therapy presented lower serum cortisol levels than the individuals did not use this drug (Mühlbauer and Müller-Oerlinghausen 1985).

The antioxidant defenses were influenced by the dose, source, and tissue analyzed (Fig. 4A). The liver showed the highest levels of antioxidant enzymes, which indicate that this organ is the most affected by Li2CO3, mainly in high concentrations of Li in the LiS diet (Fig. 4A). The rats that were fed a lithium diet had higher activity of SOD and CAT than the control. However, these enzymatic activities can be related to a higher level of oxidative stress due to the high levels of MDA (Nciri et al. 2009, 2012). In our study, although the activity of these enzymes is higher in treatments with Li, the M + LiT diet had lower lipid peroxidation than control and LiS (high dosage). Thus, the dosage and form of Li caused less oxidative damage to the liver than in the control and Lis diets (Fig. 4B).

The GST had a different behavior depending on the tissue analyzed. The brain showed difference among the treatments. LiS diet had GST levels 4 times higher than other treatments. This result may indicate an oxidative damage in the tissues of these animals (LiS) which is evidenced by the high levels of MDA. Highest levels of cerebral GST in rats were found at higher dosages of Li (Shao et al. 2008), but no dosage exceeded the therapeutic dosage, as is the case with LiS treatment of our study. Analyzing neural cells of rats, it was found that the generation of reactive oxygen species is directly proportional to doses of Li2CO3 (Yousefsani et al. 2020). In general, the highest MDA levels were found in the LiS treatment in all tissues, except for the kidneys. In this organ, it was observed the highest MDA levels in the control that received neither Li nor mushroom. Thus, maybe lithium or mushroom is protecting kidneys against lipid peroxidation. Furthermore, comparing the results obtained from the M + LiT treatment for antioxidant enzymes (which in general had the greatest activities) with the levels of MDA, the enriched mushroom, in addition to increasing the activity of these enzymes, is also a protective agent against oxidative stress in analyzed tissues.

Conclusions

This is the first in vivo report on the bioavailability of Li-enriched mushrooms in pigs. The findings demonstrate that the Li-enriched mushroom is a more bioavailable source of Li when compared to lithium carbonate. Cortisol is an important marker of stress responding well to Li concentrations. The activity of enzymes is influenced by the concentrations and forms of Li provided and MDA proved to be a coherent marker of oxidative stress in pigs. Thus, the Li-enriched mushrooms of the isolate of P. djamour, PLO 13, present high potential and can be an alternative source for suppling this mineral in the diet of humans, as a food supplement, due to its various beneficial properties to the organism or even in the therapeutic treatment of diseases that use to use Lithium.

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful to the Cordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível superior (Capes-0001), Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) and Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa de Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG) for their financial support.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, Validation, Investigation, Writing, Formal analysis: L. S. Lopes, M.C.S. da Silva, J.S. da Silva, J.M.R. da Luz, A. O. Faustino, Gabriel C. Rocha, L. L. Oliveira, M. C. M, Kasuya. Data processing and analysis: L. S. Lopes, M.C.S. da Silva, J.S. da Silva, J.M.R. da Luz, M. C. M, Kasuya. The investigation, Writing - review & editing: L. S. Lopes, M.C.S. da Silva, J.S. da Silva, J.M.R. da Luz, A. O. Faustino, Gabriel C. Rocha, L. L. Oliveira, M. C. M, Kasuya.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the study reported in this paper.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of National Council for the Control of Animal Experimentation (CONCEA, Law number 11,794, of October 8, 2008) and Commission of Ethics in the Use of Animal Production of the Universidade Federal de Viçosa (Protocol No. 02/2021). All participants of the QDA and Napping panels were provided with consent forms before taking part in this study.

Contributor Information

Leandro de Souza Lopes, Email: souzalopesleandro@gmail.com.

Marliane de Cássia Soares da Silva, Email: marliane.silva@ufv.br.

Juliana Soares da Silva, Email: julianass2007@hotmail.com.

José Maria Rodrigues da Luz, Email: josemarodrigues@yahoo.com.br.

Alessandra de Oliveira Faustino, Email: faustino@ufv.br.

Gabriel Cipriano Rocha, Email: gcrocha@ufv.br.

Leandro Licursi de Oliveira, Email: leandro.licursi@ufv.br.

Maria Catarina Megumi Kasuya, Email: mkasuya@ufv.br.

References

- Aebi H. Catalase in vitro. Methods Enzymol. 1984;105:121–126. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(84)05016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barjasteh-Askari F, Davoudi M, Amini H, Ghorbani M, Yaseri M, Yunesian M, Lester D. Relationship between suicide mortality and lithium in drinking water: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect. 2020;264:234–241. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bschor T, Adli M, Baethge C, Eichmann U, Ising M, Uhr M, Bauer M. Lithium augmentation increases the ACTH and cortisol response in the combined DEX/CRH test in unipolar major depression. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2002;27(3):470–478. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(02)00323-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buege JA, Aust SD. Microsomal lipid peroxidation. In Methods in enzymology. Academic Press. 1978;52:302–310. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(78)52032-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva MC, Naozuka J, da Luz JMR, de Assunção LS, Oliveira PV, Vanetti MC, Kasuya MC. Enrichment of Pleurotus ostreatus mushrooms with selenium in coffee husks. Food Chem. 2012;131(2):558–563. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.09.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Assunção LS, da Luz JMR, da Silva MDCS, Vieira PAF, Bazzolli DMS, Vanetti MCD, Kasuya MCM. Enrichment of mushrooms: an interesting strategy for the acquisition of lithium. Food Chem. 2012;134(2):1123–1127. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieterich S, Bieligk U, Beulich K, Hasenfuss G, Prestle J. Gene expression of antioxidative enzymes in the human heart: increased expression of catalase in the end-stage failing heart. Circulation. 2000;101(1):33–39. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.101.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dol I, Knochen M, Vieras E. Determination of lithium at ultratrace levels in biological fluids by flame atomic emission spectrometry. Use of first-derivative spectrometry. Analys. 1992;117(8):1373–1376. doi: 10.1007/s11064-006-9139-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efendiev AM, Kerimov BF. The effect of starvation of lipid peroxidation in synaptosomal and mitochondrial factions of various brain structures. Vopr Med Khim. 1994;40(2):34–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faria MGI, Avelino KV, do Valle JS, da Silva GJ, Gonçalves AC, Dragunski DC, Linde GA (2019) Lithium bioaccumulation in Lentinus crinitus mycelial biomass as a potential functional food. Chemosphere 235:538-542. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.06.218 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Garcíaa S, Fuentes L, Villegas O, Guzmán J. Distribution of lithium in different CNS areas and other tissues of adult male and female vizcacha (Lagostomus maximus maximus) J Trace Elem Med Biol. 1999;12(4):217–220. doi: 10.1016/S0946-672X(99)80061-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge W, Jakobsson E. Systems biology understanding of the effects of lithium on cancer. Front Oncol. 2019;9:296. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.00296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin M. Lithium side effects and toxicity: prevalence and management strategies. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2016;4(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s40345-016-0068-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habig WH, Pabst MJ, Jakoby WB. Glutathione S-transferases: the first enzymatic step in mercapturic acid formation. J Biol Chem. 1974;249(22):7130–7139. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)42083-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillert M, Zimmermann M, Klein J. Uptake of lithium into rat brain after acute and chronic administration. Neurosci Lett. 2012;521(1):62–66. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2012.05.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu T, Hui G, Li H, Guo Y. Selenium biofortification in Hericium erinaceus (Lion’s Mane mushroom) and it’s in vitro bioaccessibility. Food Chem. 2020;331:127287. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.127287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwai M, Kondo F, Suzuki T, Ogawa T, Seno H. Application of lithium assay kit LS for quantification of lithium in whole blood and urine. Legal Med. 2021;49:101834. doi: 10.1016/j.legalmed.2020.101834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessing LV, Gerds TA, Knudsen NN, Jørgensen LF, Kristiansen SM, Voutchkova D, Ersbøll AK. Association of lithium in drinking water with the incidence of dementia. JAMA Psychiat. 2017;74(10):1005–1010. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.2362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen NN, Schullehner J, Hansen B, Jørgensen LF, Kristiansen SM, Voutchkova DD, Ersbøll AK. Lithium in drinking water and incidence of suicide: a nationwide individual-level cohort study with 22 years of follow-up. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(6):627. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14060627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes LS, da Silva MCS, Faustino AO, Oliveira LL, Kasuya MCM. Bioaccessibility, oxidizing activity and co-accumulation of minerals in Li-enriched mushrooms. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2022;155:112989. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2021.112989. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Miró S, Tecles F, Ramón M, Escribano D, Hernández F, Madrid J, Cerón JJ. Causes, consequences and biomarkers of stress in swine: an update. BMC Vet Res. 2016;12(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12917-016-0791-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath JJ, Berk M. Could lithium in drinking water reduce the incidence of dementia? JAMA Psychiat. 2017;74(10):983–984. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.2336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mühlbauer HD, Müller-Oerlinghausen B. Fenfluramine stimulation of serum cortisol in patients with major affective disorders and healthy controls: further evidence for a central serotonergic action of lithium in man. J Neural Transm. 1985;61(1):81–94. doi: 10.1007/BF01253053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nciri R, Allagui MS, Vincent C, Murat JC, Croute F, El Feki A. The effects of subchronic lithium administration in male Wistar mice on some biochemical parameters. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2009;28(10):641–646. doi: 10.1177/0960327109106486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nciri R, Allagui MS, Bourogaa E, Saoudi M, Murat JC, Croute F, Elfeki A. Lipid peroxidation, antioxidant activities and stress protein (HSP72/73, GRP94) expression in kidney and liver of rats under lithium treatment. J Physiol Biochem. 2012;68(1):11–18. doi: 10.1007/s13105-011-0113-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oruch R, Elderbi MA, Khattab HA, Pryme IF, Lund A. Lithium: a review of pharmacology, clinical uses, and toxicity. Eur J Pharmacol. 2014;740:464–473. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheid SS, Faria MGI, Velasquez LG, do Valle JS, Gonçalves AC, Dragunski DC, Linde GA. (2020). Iron biofortification and availability in the mycelial biomass of edible and medicinal basidiomycetes cultivated in sugarcane molasses. Sci Rep 10(1):1-6. 10.1038/s41598-020-69699-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Schrauzer GN. Lithium: occurrence, dietary intakes, nutritional essentiality. J Am Coll Nutr. 2002;21(1):14–21. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2002.10719188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahzad B, Mughal MN, Tanveer M, Gupta D, Abbas G. Is lithium biologically an important or toxic element to living organisms? An Overview. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2017;24(1):103–115. doi: 10.1007/s11356-016-7898-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao L, Cui J, Young LT, Wang JF. The effect of mood stabilizer lithium on expression and activity of glutathione s-transferase isoenzymes. Neurosci. 2008;151(2):518–524. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szklarska D, Rzymski P. Is lithium a micronutrient? From biological activity and epidemiological observation to food fortification. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2019;189(1):18–27. doi: 10.1007/s12011-018-1455-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedesco MJ, Tedesco MJ, Gianello C, Bissani CA, Bohnen H, Volkweiss SJ, Volkweiss S (1995) Analysis of soil, plants and other materials (2nd edition)

- Tellez N, Comabella M, Julià EV, Río J, Tintoré MA, Brieva L, Montalban X. Fatigue in progressive multiple sclerosis is associated with low levels of dehydroepiandrosterone. Mult Scler J. 2006;12(4):487–494. doi: 10.1191/135248505ms1322oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uribe-Wandurraga ZN, Igual M, García-Segovia P, Martínez-Monzó J. In vitro bioaccessibility of minerals from microalgae-enriched cookies. Food Funct. 2020;11(3):2186–2194. doi: 10.1039/C9FO02603G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieira PAF, Gontijo DC, Vieira BC, Fontes EA, de Assunção LS, Leite JPV, Kasuya MCM. Antioxidant activities, total phenolics and metal contents in Pleurotus ostreatus mushrooms enriched with iron, zinc or lithium. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2013;54(2):421–425. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2013.06.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wen J, Sawmiller D, Wheeldon B, Tan J (2019) A review for lithium: pharmacokinetics, drug design, and toxicity. CNS Neurol Disorders Drug Targets (Formerly Current Drug Targets-CNS & Neurological Disorders) 18(10): 769–778. 10.2174/1871527318666191114095249 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Won E, Kim YK. An oldie but goodie: lithium in the treatment of bipolar disorder through neuroprotective and neurotrophic mechanisms. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(12):2679. doi: 10.3390/ijms18122679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao CJ, Lin CW, Lin-Shiau SY. Altered intracellular calcium level in association with neuronal death induced by lithium chloride. J Formos Medic Assoc. 1999;98(12):820–826. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yousefsani BS, Askian R, Pourahmad J. A new approach on lithium-induced neurotoxicity using rat neuronal cortical culture: Involvement of oxidative stress and lysosomal/mitochondrial toxic Cross-Talk. Main Group Met Chem. 2020;43(1):15–25. doi: 10.1515/mgmc-2020-0003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, He L, Yang Z, Li L, Cai W. Lithium chloride promotes proliferation of neural stem cells in vitro, possibly by triggering the Wnt signaling pathway. Anim Cells Syst. 2019;23(1):32–41. doi: 10.1080/19768354.2018.1487334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]