Abstract

Approximately 25% to 35% of individuals diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder (ASD) do not acquire vocal speech and may require an augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) modality to express their wants and needs. There are various modes of AAC that individuals with limited vocal speech may use (e.g., manual signs, picture cards). However, the process used to identify the most appropriate communication modality for an individual is not always systematic. Thus, the acquisition of the specified AAC modality may be slow if the communication modality prescribed is inappropriate. To date, there are a few methods that may be used to select an AAC modality. However, these methods consider different variables. For example, McGreevy et al. (2014) included a communication assessment within the Essential for Living (EFL) manual that identifies and ranks appropriate AAC modalities for individuals. Nevertheless, to date, there is no research demonstrating that individuals will acquire the communication modality recommended by the EFL or comparing acquisition of this AAC modality to other frequently used AACs. Thus, this study aimed to compare acquisition of mands across three AACs, evaluate whether mands taught using the AAC modality recommended by the EFL were acquired in fewer sessions, and determine whether participants preferred the AAC modality acquired in fewer sessions. Four children diagnosed with ASD and limited vocal repertoires participated in this study. All participants acquired mands using the AAC modality recommended by the EFL. However, for all participants, rate of acquisition was similar across all three modalities of AAC and preference of AAC was idiosyncratic.

Keywords: Alternative and augmentative communication (AAC), Communication modalities, Essential for Living, Mand training, Preference

Approximately 25% to 35% of individuals diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder (ASD) have limited vocal communication (Lord & Jones, 2012) and may require an augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) modality. Individuals with limited vocal repertoire can use one of various modes of AAC (e.g., speech generating devices, manual signs, picture cards) to communicate their wants and needs. However, the process used to identify the most appropriate communication modality for an individual is not always systematic. As a result, acquisition of communication skills using the specified AAC modality may be slow if the communication modality prescribed is inappropriate given the individual’s skills repertoire.

To date, the literature has described a few methods for the selection of an AAC modality. Partner competence is a method first described by Bryen et al. (1988) that emphasizes choosing an AAC that others in the environment (e.g., teachers, caregivers) can teach and reinforce adequately in natural settings. However, this method does not consider the individual’s skills and potential prerequisites needed to acquire one of these AAC modalities. Another method for selecting an AAC was described by Jones et al. (1990). Jones et al.’s method considers the communicative needs of the individual, environmental demands, and contextual characteristics. This method requires assessing the individual’s mobility, posture, hand function, vision, ocular-motor, hearing, symbolic and verbal comprehension, and communicative functions and modes. However, it does not consider the individual’s level of problem behavior, the size of the verbal community, or individual’s preference.

Results of previous studies on functional communication training (FCT) suggest that mand modality proficiency and relative preference for communication modalities are additional variables that should be considered in determining which AAC modality is most appropriate for specific individuals. For instance, Ringdahl et al. (2009) conducted a mand topography assessment prior to FCT. During the mand topography assessment three to four AAC modalities were available, and the participant was provided with 10 opportunities to emit a functional communicative response (FCR) with each of the AAC modalities. A three-prompt sequence (i.e., vocal, model, physical) was used and data were recorded on the type of prompt needed for the participant to emit the FCR. The mand topography assessment identified a high proficiency (i.e., at least 50% of trials required vocal prompts only) and a low proficiency (i.e., at least 50% of trials required model or physical prompts) AAC modality for each participant. Results of the FCT evaluation, which included both the high and low proficiency AACs, indicated that overall better outcomes (e.g., fewer instances of problem behavior, more instances of appropriate mands) were attained with the high proficiency AAC modality. Ringdahl et al. (2016) evaluated preference for communication modalities (AAC and vocal responses) following FCT. Each participant was taught to emit a FCR using two different communication modalities and relative preference for each modality was evaluated during a FCT condition during which both modalities were concurrently available, and responses emitted using either of them were reinforced. Results indicated that all participants demonstrated a preference for one of the communication modalities, however, a different number of sessions (i.e., 5 sessions, 6–10 sessions, more than 10 sessions) was necessary to attain differentiated responding across participants.

Few studies have continued to evaluate acquisition of communication skills, among other factors, to identify the most appropriate AAC modality for individuals with limited communication. For instance, LaRue et al. (2016) evaluated acquisition of tacts across various AAC modalities to determine which modality results in fastest acquisition. In this study all participants acquired tacts in fewer training sessions with a particular AAC modality and participants preferred the AAC modality associated with faster acquisition. Likewise, Van der Meer et al., (2012) assessed acquisition of mands across various AAC modalities as well as participants’ preference for these AAC modalities. In this study rate of acquisition and participants’ preferences were idiosyncratic. This means that there was no correlation between the rate of acquisition and the participants’ preference. Finally, in a study by Valentino et al. (2019), authors evaluated participants’ motor imitation, matching, and echoic repertoires to determine whether these repertoires were predictive of acquisition of mands across manual signs, picture exchanges, and vocalizations. Results indicated that vocal mands were acquired in fewer sessions only by the participant who performed well during the echoic assessment.

The Essential for Living (EFL; McGreevy et al., 2014) handbook is a functional skills curriculum for individuals with moderate-to-severe disabilities. The EFL contains a chapter on “Methods of Speaking” that helps clinicians determine when a mode of communication other than vocalizations (i.e., “saying words”) should be considered and it includes a communication modality assessment that considers the individual’s skills repertoire, level of problem behavior, similarities between AAC and the mode of communication used by the verbal community, and size of verbal community. This assessment identifies primary and secondary modes of AAC for the individual based on all of these variables. The authors of the EFL, however, do not suggest that the modality identified in the EFL will result in faster acquisition than other modalities nor do they suggest that the modality identified will be preferred by the individual. Nevertheless, to date, there is no research demonstrating that individuals will acquire the communication modality recommended by the EFL or comparing acquisition of this AAC modality to other frequently used AACs. Thus, the purpose of this study was to assess acquisition of mands using the AAC modality recommended by the EFL. In particular, this study aimed to compare acquisition of mands across various AACs, evaluate whether mands taught using the AAC modality recommended by the EFL were acquired in fewer sessions, and determine whether participants preferred the AAC modality acquired in fewer sessions.

Method

Participants and Settings

Participants were four children diagnosed with an ASD who had a limited vocal repertoire. In particular, per report of each participant’s caregiver or board certified behavior analyst (BCBA) they either emitted no contextually appropriate vocal behavior or their vocal repertoire included fewer than 15 recognizable words (e.g., juice, mom) or sounds (e.g., “da,” “ta,” “oh”). None of the participants engaged in severe problem behavior (e.g., self-injury, aggression, property destruction). In addition, prior to participating in this study each participant already used an AAC modality, which was chosen by their BCBA or their caregiver. The rationales and/or procedures used to select the specific communication modality for each participant is unknown.

Daphne was a 4-year-old European-American female who was learning to use a picture exchange system as her primary mode of communication. Daphne did not mand independently using this communication modality, and her vocal repertoire consisted of fewer than 10 nonfunctional but spontaneous approximations to words. Her caregivers reported that unfamiliar individuals had difficulty understanding her vocalizations. Daphne followed simple one-step instructions such as “clap your hands.” Moreover, Daphne did not attend school at the time of the study, but she received ABA therapy in a clinic during morning hours. Her BCBA had selected picture exchange as the communication modality to teach her. However, from the onset of picture exchange training that was part of her ABA therapy, Daphne was required to place the picture of the item she wanted on a sentence strip that read “I want.”

Alo was a 2-year-old Native American male who was learning to use a picture exchange system to communicate. At the time of this study, Alo could independently mand for two to three items using his picture exchanges, but his vocal repertoire consisted of two sounds (i.e., “ba,” “da”) that were spontaneous but not functional. He often manded for an item by leading people to the location of the specific item and pointing to the item. Alo did not follow vocally delivered instructions without prompts. Alo attended a preschool where he received ABA therapy for 30 h a week. Alo’s BCBA had selected picture exchange as the communication modality to teach him.

Daniel was a 3-year-old Hispanic male who was learning to use a picture exchange system as his primary mode of communication. Daniel did not mand independently using this communication modality, and his vocal repertoire consisted of 5 to 10 spontaneous but nonfunctional spoken words. His caregivers reported that unfamiliar individuals had difficulty understanding his vocalizations. In addition, Daniel did not follow vocally delivered instructions without prompts. Prior to his participation in this study, Daniel received ABA therapy for less than 3 months. His ABA therapy was provided at a clinic, during the morning hours, three times a week. Daniel did not attend school. His BCBA had selected picture exchange as the communication modality to teach him.

Walter was an 8-year-old Caucasian male who used a speech generating device and manded for items when prompted. He did not independently mand using the speech generating device and his vocal repertoire consisted of 10–15 spontaneous but not functional words. His caregivers reported that familiar and unfamiliar individuals sometimes had difficulty understanding his vocalizations. Walter followed one-step vocal instructions such as “touch your head.” Walter attended school and was placed in a special education classroom. Walter received approximately 40 h a week of ABA therapy across school, clinic, and home settings. Walter’s caregivers reported that they had selected the speech generating device as his communication modality.

Daphne’s and Daniel’s sessions were conducted in therapy rooms inside of the ABA clinics where they received ABA services. Alo’s sessions were conducted at his preschool in the same room where he typically received ABA services. Walter’s sessions were conducted in his home and at a therapy room in the clinic where he received ABA services. Sessions for all participants were usually conducted during the late afternoon before snack time. All edible items used during sessions were restricted throughout the day and only available during sessions.

Materials

Materials for this study included the edibles used during preference assessments and mand training, different picture cards or icons placed in each of the participants’ picture exchange or speech generating device, and iPads programed with Proloquo (Daphne, Daniel, Walter) or Visuals2Go (Alo) for the speech generating device modality. In addition, a 7 × 10 cm picture of each modality (i.e., picture exchange, manual sign, and speech generating device) were used for the communication modality preference assessment. The picture used to depict the picture exchange modality consisted of a picture exchange book, the picture for speech generating device consisted of an iPad with Visuals2Go or Proloquo on the screen, and the picture for manual sign consisted of the American Sign Language (ASL) sign for “more.” All pictures were photographs. Data were recorded using paper and pen and sessions were recorded using a video camera to calculate reliability and assess procedural integrity.

Response Definition and Measurement

During the EFL communication modality assessment, therapists, consisting of master students in ABA programs, collected data on the participants’ vocal, sensory, and behavioral repertoires (see EFL communication modality assessment section for detailed explanation). This assessment was completed during structured observations and during these observations data were collected on a trial-by-trial basis on whether the participant emitted, without requiring any prompts, a response appropriate to the task or activity (e.g., matched identical cards; oriented body or head towards an auditory stimulus). These responses were scored as correct. If the participant did not emit a response within 5 s of the opportunity or emitted a response that did not correspond to the task, the trial was scored as incorrect. One structured observation was completed with each participant and during this observation the environment was manipulated to ensure the participant had five opportunities to emit a response for each of the skills evaluated (e.g., five opportunities to mand). To summarize the data from the structured observation, percentage of opportunities with correct responses was calculated by dividing the correct number of responses for each of the skills by five and multiplying by 100. If the participant responded correctly on at least 80% of the opportunities, the skill was deemed as part of the participant’s repertoire.

During the edible and the communication modality preference assessments, data were collected on the participants’ stimulus selection. Selection was defined as the participant grabbing and placing the food item in their mouth (edible preference assessment) or grabbing one picture and giving it to the therapist (communication modality preference assessment) within 5 s of the onset of the trial. The percentage of opportunities each item (food or picture) was chosen was calculated by dividing the number of trials selected by the total number of trials each item was available and multiplied by 100 to yield a percentage.

The mand modality training phase included an initial assessment to determine if participants could emit mands for the preferred items with any of the AAC modalities selected. During the initial assessment the three AAC modalities were available on each trial and data were collected on a trial-by-trial basis on correct independent responses, correct prompted responses, and incorrect responses. An independent correct response was defined as the emission of a response using any of the communication modalities available, within 5 s of the initial vocal prompt “What do you want?,” which corresponded to the target preferred edible. Responses that were accurate but required a second vocal prompt (i.e., “If you want something, please let me know”) from the therapist were scored as prompted correct responses. Incorrect responses were defined as instances in which the participant did not emit a response within 5 s of the initial vocal prompt “What do you want?” or emitted a response before or after the second vocal prompt that did not meet the definition for independent or prompted correct response. Percentage of trials with correct independent responses were calculated by dividing the number of trials the child emitted an independent correct response by the total number of trials in a session and multiplied by 100 to yield a percentage.

Following the initial assessment, the mand training comparison was conducted and it included two phases, baseline and mand training. During these phases, data were collected on a trial-by-trial basis on independent correct responses, prompted correct responses, or incorrect responses. Independent correct responses consisted of the emission of a response in the target communication modality before a prompt was delivered. Prompted correct responses consisted of responses emitted while a hand-over-hand prompt was provided. Incorrect responses consisted of instances in which the participant emitted a response that did not meet the definition for independent or prompted correct response. Percentage of trials with correct independent responses were calculated by dividing the number of trials the child emitted an independent correct response by the total number of trials in a session and multiplied by 100.

Interobserver Agreement (IOA) and Procedural Integrity (PI)

Graduate students served as therapists and data collectors. To collect reliability, therapists independently scored sessions by directly observing the session or by reviewing videos. Across all phases of this study, interobserver agreement (IOA) was calculated on a trial-by-trial basis by dividing the number of trials with agreement by the total number of trials and multiplying the results by 100. Interobserver agreement was calculated for 38% of Daphne’s sessions with a mean IOA score of 93% (range: 60%–100%), 42% of Alo’s sessions with a score of 100%, 42% of Daniel’s sessions with a mean IOA score of 97% (range: 90%–100%), and 38% of Walter’s sessions with a mean IOA score of 99% (range: 90%–100%).

Across all phases of this study, therapist procedural integrity was assessed using task analyses (available upon request) of the steps to be completed during each of the assessments and evaluations. Procedural integrity data were collected during sessions to ensure that all therapists implemented the procedures as specified in the task analyses. Examples of the procedural steps included in the task analysis for mand training comparison included having the necessary materials available to conduct sessions, placing target stimuli within eyesight of the participant, waiting for the participant to show interest toward the target stimuli (e.g., looking for it; reaching for the item) before starting the trial, providing the initial vocal prompt “What do you want?,” providing hand-over-hand prompt during training, reinforcing only correct responses with the correct edible item, and providing no programmed consequences for incorrect responses. Procedural integrity was assessed by a single observer for 38% of Daphne’s sessions with a mean score of 99% (range: 92%–100%), 43% of Alo’s sessions with a score of 100%, 40% of Daniel’s sessions with a mean score of 99% (range: 92%–100%), and 38% of Walter’s sessions with a mean score of 99% (range: 94%–100%).

Experimental Design

This study used a nonconcurrent multiple probe (Watson & Workman, 1981) across participants with an adapted alternating treatments design (Sindelar et al., 1985). That is, acquisition of three different responses (i.e., mands), equated for difficulty, were compared across three different communication modalities (i.e., interventions). However, data are depicted as sessions instead of days to facilitate visual inspection. At least one session of each condition was completed per day. Difficulty of the mands taught was equated across modalities by ensuring that the participant was required to emit only one response (i.e., select a picture, press a button, engage in one gesture) for each modality. Although a sentence strip was available on Daphne’s picture exchange, reinforcement was contingent on the selection of the correct picture independent of whether she placed the picture on the sentence strip. In addition, if she placed the picture on the sentence strip, she was not required to provide the sentence strip to the therapist (see Table 1). Moreover, the mand acquisition evaluation was conducted twice, using new target stimuli, with two of the participants (Daniel and Walter) to assess for within-participant replication. All procedures completed during the first mand modality training were replicated during the second mand modality training with Daniel and Walter with the exception that new stimuli were used. Meaning, new icons (for the speech generating device) and pictures (for the picture exchange) were used. The manual sign for Daniel remained the same during both mand modality trainings. The manual signs for Walter were different across the two mand modality comparisons.

Table 1.

Format and definition of correct responses for each modality for each participant

| Modality | Participants | Modality Arrangement | Definition of Correct Response |

|---|---|---|---|

| Manual Sign |

Alo Daphne Daniel Walter |

No additional materials were present. Only the edible in front of the participant | Making the correct gesture for the item |

| Speech Generating Device |

Alo Daphne Daniel Walter |

iPad programmed with Visuals2Go or Proloquo containing nine icons. Edible in front of the participant | Pressing the icon corresponding to the correct item with enough force to generate audio in the iPad programmed with Visuals2Go or Proloquo |

| Picture Exchange |

Alo Daniel Walter |

Laminated picture board with 10 laminated picture cards with Velcro. Edible in front of the participant | Selecting the picture depicting the correct item |

| Picture Exchange | Daphne | Laminated picture board with an “I want” sentence strip Velcro at the top and ten laminated picture cards with Velcro. Edible in front of the participant | Selecting the picture depicting the correct item or selecting and placing the picture of the correct item on the sentence strip next to “I want.” The participant was not required to hand the sentence strip to the therapist |

Phase I: Pre-Assessments

Essential for Living (EFL) Communication Modality Assessment

The purpose of the EFL communication modality assessment is to identify, if necessary, an alternative mode of communication for individuals who may have limited or unintelligible vocal behavior. The assessor who generally conducts this assessment is not identified in the EFL. In other words, the EFL does not provide information about the assessor qualifications needed to adequately conduct the assessment. However, given that this assessment is generally used in applied behavior analytic settings, it might be best for this assessment to be implemented by a behavior analyst or an individual with experience in the field of applied behavior analysis who has been trained in using the EFL communication modality assessment. All individuals who implemented the assessment for the participants in the study were either master’s students or doctoral students in applied behavior analysis programs. These students received training on the use of the assessment tool prior to implementing it on their own.

The first step in determining the most appropriate communication modality is to determine the vocal profile of the participant. The EFL includes six vocal profiles. Individuals within vocal profile 1 engage in vocal behavior that is similar to the vocal behavior of a typically developing peer. That is, individuals who fall in this profile engage in spoken words that are spontaneous and understandable. In general, these individuals do not need an alternative communication modality. By contrast, individuals who fall in vocal profile 6 have limited vocal behavior. In particular, individuals who fall in this profile may emit some vocal sounds but they do not have spoken words. These individuals do need an alternative mode of communication. Vocal profiles 2 to 5 are for individuals who fall in-between profiles 1 and 6. These may be individuals who have few spoken words that may or may not be functional, spontaneous, or understandable. In general, for individuals with vocal profiles 1 or 2, vocalizations are deemed as an appropriate method of communication. For individuals with vocal profiles 3 or 4, vocal communication should be attempted first, and if inadequate progress is made, then an alternative mode of communication should be identified. For individuals with vocal profiles 5 or 6, an alternative mode of communication is recommended (see McGreevy et al., 2014, for specific recommendations for each vocal profile).

Next, to identify the most appropriate alternative method of communication for those individuals who have deficits related to their vocal repertoire, the assessor evaluates the participant’s sensory, skills, and behavioral repertoires including the participant’s activity level, their hearing, their sight, ability to walk, fine motor coordination, motor imitation, matching skills, and their level of problem behavior. Although the EFL handbook provides detailed instructions on the selection of a vocal profile, it does not describe a specific method for assessing the characteristics of the individuals for which a vocal profile must be identified. Thus, in this study, to determine the vocal profile for each of the participants, caregiver interviews and structured observations were conducted.

Caregiver Interview

During the interview, caregivers were asked questions regarding their children’s vocal behavior and their sensory, skills, and behavioral repertoires to assist in the identification of a vocal profile. The caregiver interview was developed by the research team and no medical records were reviewed to confirm the information provided by the caregivers during the interview. However, many of the skills indirectly assessed during the caregiver interview were directly assessed by the research team during the structured observation. The questions in the interview included information about their children’s spoken words (e.g., Does your child have any spoken word? If yes, how many? Are these words spontaneous?), hearing (e.g., Can your child hear?), sight (e.g., Can your child see?), ability to ambulate (e.g., Is your child ambulatory?), activity level (e.g., Is your child typically activate?), fine motor coordination (e.g., Does your child have fine motor coordination?), motor imitation (e.g., Can your child imitate others’ behavior?), matching (e.g., Can your child match pictures to objects?), and problem behavior (e.g., Does your child have any problem behavior? If so, what are the behaviors you find problematic?).

Structured Observation

Following the caregiver interview, therapists conducted a 30-min structured observation of each participant in which the participant’s environment was manipulated to assess their vocal behavior and their sensory, skills, and behavioral repertories. During the structured observation each target skill was tested five times. For example, to identify if the participant had any vocal behavior, therapists withheld highly preferred items and waited up to 30 s to see if the participant manded for the item. To determine if the participant could hear, therapists played preferred sounds (e.g., cartoons) in different locations of the room and measured whether the participant oriented their body (e.g., head, full body) towards the location of the sound. To assess if the participant could see, therapists held preferred items within the eyesight of the participant, but at different locations, and recorded whether the participant oriented their eyes towards the location of the items. To assess if the participant was ambulatory, therapists called the participant from different places in the room and offered a preferred item for the participant to walk towards the therapist. To assess if the participant was active, therapists placed different preferred items around the room and recorded if the participant walked to grab the toys or gave them to the therapist to play. To assess the participant’s fine motor coordination, therapists asked the participant to complete different age-appropriate tasks (e.g., string beads; place shapes into a shapes cube; trace a line using a crayon). To assess the participant’s motor imitation, the therapist engaged in simple motor tasks (e.g., put arms up, sit down, clap hands) and asked the participant to perform the same action (e.g., “do this”). To assess the participant’s matching skills, therapists provided the participant with an array of matching cards (i.e., five pictures of animals or five colored cards) and then gave the participant access to a card that was identical to one of the items in the array. To assess for participant’s socially maintained problem behavior, therapists withheld access to preferred toys, adult attention, and asked the participant to engage in nonpreferred tasks identified by the caregivers. In addition, therapists recorded data on all problem behavior that occurred during the structured observations. It is important to note that participants did not always comply with all activities presented during the structured observations and that some problem behavior occurred during some observations. However, the problem behavior and lack of compliance that occurred were not severe and did not appear to affect the results of the structured observation. In addition, to mitigate problem behavior and potentially increase general compliance, therapists played with the participants and provided praise before and after sessions.

Vocal Profile and EFL Communication Modality Selection

The results from the caregiver interviews and structured observations were used to identify a vocal profile for each participant. These results suggested that Daphne, Daniel, and Walter emitted a few spoken words or sounds (e.g., 5–15) that were not understood by unfamiliar individuals and were used unfunctionally whereas Alo emitted only two sounds and no spoken words. All four participants were able to hear, see, and walk independently. In addition, they were all considered active children. Daphne, Daniel, and Walter engaged in independent matching of simple pictures. Alo did not engage in independent matching. Daphne and Walter had motor coordination and none of the participants engaged in severe problem behavior. Based on these results, we identified the level of vocal behavior and sensory, skills, and behavioral repertoires and selected vocal profile 4 for Daphne, Daniel, and Walter, and vocal profile 6 for Alo. Per the EFL handbook vocal profile 4 includes individuals who emit “Uncontrolled or Controlled Spoken-Word Repetitions are not Understandable” (McGreevy et al., 2014, p. 47) whereas vocal profile 6 includes individuals who emit “Noises, a Few sounds, and Syllables” (McGreevy et al., 2014, p. 48).

Although the EFL handbook recommends consulting with a speech-language pathologist for individuals with a vocal profile 4 to determine whether vocalizations or an alternative method of communication should be targeted, given that Daphne, Daniel, and Walter were already using an AAC modality, we proceeded with the identification of an alternative mode of communication for them and for Alo. An alternative mode of communication was selected by using the online tool provided by the EFL publishers (http://amscompare.com). The alternative modes of speaking (AMS) comparison tool opens upon entering this website and information on how the comparison tool works and how it is used are provided. A list of boxes is available at the bottom of the website. Here, information about the participant’s sensory, skills, and behavioral repertories is entered. In particular, the boxes corresponding to skills that the participant has in their repertoire are clicked. For example, if the participant can hear, component “H” should be clicked, if the participant cannot hear, component “HI,” which stands for hearing impaired, should be clicked. Every time a selection is made, the components change from the color gray to the color yellow. After selecting all appropriate participant’s characteristics, the “comparing alternative modes of speaking” button should be clicked and then the tool generates a list of potential communication modalities for the participant ranked from most appropriate to least appropriate. The number of communication modalities identified, and their corresponding rank considers the advantages and disadvantages (e.g., portability, effort, complexity, communication skills) of each modality in comparison to a vocal repertoire, the participant’s sensory, skills, and behavioral repertoires, and potential size of verbal community (i.e., large audience). In the case of our participants, differing ranks were assigned to each specific AAC modality recommended by the EFL. The highest ranked AAC for Daphne and Walter was AMS #1 (“Using the sign language of the deaf community”; McGreevy et al., 2014, p. 156) and AMS #3 (“Forming a repertoire of standard, adapted, and idiosyncratic signs”; McGreevy et al., 2014, p. 156) for Daniel. Thus, the top recommended communication modality for all three individuals was a form of a manual sign. For Alo, the top recommended communication modality was AMS #6 (“Writing words or drawing diagrams on a small notepad”; McGreevy et al., 2014, p. 156). However, because this skill was not age appropriate for Alo as he was only 2 years old, the second highest ranked modality identified by the EFL, AMS #2 (“Forming standard signs”; McGreevy et al., 2014, p. 156), was chosen. Thus, based on results of this assessment all participants were taught mands using manual signs.

Identification of Comparison Communication Modalities

To compare rate of mand acquisition in three different modalities, following the identification of the EFL communication modality, two additional communication modalities commonly used in clinical practice were identified. To do this, the advantages and disadvantages of each alternative communication modality in comparison to vocal communication (e.g., portability, effort, complexity, communication skills) and the size of the person’s verbal community were considered. In addition, because all participants had similar characteristics and they were already learning to use picture exchange (Daphne, Alo, and Daniel) or a speech generating device (Walter), these two modalities (i.e., picture exchange and speech generating device) were used as the comparison communication modalities. Thus, acquisition of mands across picture exchange, a speech generating device, and manual sign were compared.

Edible Preference Assessment

Following the identification of the AAC modalities to include in the mand modality training, interviews with the caregivers, BCBAs, or both, were conducted using the Reinforcer Assessment for Individuals with Severe Disability (RAISD; Fisher et al., 1996) to identify items to be included in the preference assessments. The multiple stimulus without replacement (MSWO; DeLeon & Iwata, 1996) format was used for Daphne, Daniel, and Walter. The MSWOs for each participant included five to seven edible items. For Alo, the paired-stimulus (Fisher et al., 1992) format was used and each assessment included 12 edible items.

Data for the MSWOs were summarized using a point weighting scoring method similar to the one described by Ciccone et al. (2005). That is, points were assigned to each item based on the trial in which it was selected during each session of the preference assessment (e.g., in a six-trial session, trial 1 resulted in six points, trial 2 resulted in five points). The scores received by each item in each of the sessions were then added to obtain a total score for each item. For all participants, items that received 75% or more of the total number of points in the MSWOs or were selected in 75% or more trials in the paired stimulus preference assessment were defined as highly preferred and used during mand training.

Phase II: Mand Modality Comparison

Prior to starting baseline, we assessed whether the participants could independently mand for any of the highly preferred items using any of the AAC modalities selected for the mand training evaluation. Therefore, during each trial, all AAC modalities were available. Sessions consisted of 10 trials. At the beginning of each trial, the therapist ensured that the participant had access to all three communication modalities and that they were equidistant from the participant. The placement of the communication modalities was rotated randomly across trials to allow for the identification of a side bias. In addition, therapists presented preferred items in front of the participant but out of reach, waited for the participant to show interest toward the target stimulus (e.g., reaching towards the item), and then stated a vocal prompt (e.g., “What do you want?”). If the child engaged in a correct response, therapist provided the edible and waited until it was consumed. If the participant did not make a request within 5 s, the therapist delivered a second vocal prompt, “If you want something, please let me know.” Edibles for these assessments were selected quasi-randomly and each trial consisted of a different edible. The participant was given 30 s to make a request before the next trial began. Following no independent mands with any of the modalities, each preferred item was quasi-randomly assigned to one of the AAC modalities.

Baseline

Each baseline session consisted of 10 trials. The order in which conditions were conducted was determined randomly (i.e., selection of a paper stating the name of the condition that was placed inside of a bag). Trials were identical to the pre-baseline session with the only exceptions being (1) if participants did not make a request within the initial 5 s, therapists did not deliver vocal prompts and (2) to reinforce appropriate session behavior, therapists provided praise every three trials (e.g., “Great job sitting”; “You are doing so good today”).

Mand Training

Following stable responding during baseline, mand training was implemented. Sessions were identical to baseline with the exception that therapists provided hand-over-hand prompts to participants. For Daphne, Daniel, and Walter, across all training sessions the therapist presented the vocal response “What do you want?” and then waited 10 s before presenting the hand-over-hand prompt. That is, participants had up to 10 s to respond independently before prompts were delivered. For Alo, a prompt delay similar to the procedures implemented by Touchette and Howard (1984) was used to foster independent responding. At first, after stating the vocal response “What do you want?,” the therapist prompted the correct response using hand-over-hand immediately (i.e., 0-s delay). Following three consecutive sessions of each condition with immediate prompting, the delay increased by 2 s. In other words, the therapist provided Alo with 2 s to engage in an independent response after stating “What do you want” before providing a hand-over-hand prompt to the correct response. For all participants, initially prompted and independent correct mands resulted in access to the specified edible. Following at least 50% independent mands in one session, edibles were only provided for independent responding. Once the edible was consumed, the next trial started. If the participant engaged in an incorrect response prior to the prompt, all session materials were removed for 5 s and then therapists used hand-over-hand prompting to guide the participants to emit the correct response. No reinforcers were delivered following this error correction procedure.

The mastery criteria for Daphne, Daniel, and Walter consisted of two consecutive sessions with at least 90% correct independent mands. However, once mastery criteria were met for one modality, additional sessions for that modality were completed to ensure that performance of the mastered mand persisted. Thus, we conducted mand training sessions for these three participants until they met mastery criteria for all three communication modalities. For Daphne, Daniel, and Walter sessions continued after mastery criteria were met to ensure that rate of acquisition of the other mands was not affected by the fact that fewer conditions were in effect after mastery of the first and then the second mand. The mastery criteria for Alo consisted of three consecutive sessions with at least 90% correct independent mands. Alo’s sessions for each modality stopped after the participant mastered responding with the modality. The mastery criteria for Alo differed from the one used for the other participants because the mastery criteria for him were selected based on the criteria in place for his clinical programming at the time of the study.

Picture Exchange

During this condition, therapists placed a picture of the actual edible (e.g., picture of one Smarties) assigned as the target mand for the picture exchange condition within an array of 10 pictures of similar edible items in front of the participant. The placement of pictures within this array changed across trials to ensure the participants’ response was not controlled by the placement of the picture. The correct response topography was selecting the target picture. For Daphne, we also included a sentence strip over the array of pictures that read “I want” and reinforced either the picking up the target picture or picking up the target picture and placing it on the sentence strip. This sentence strip was added because she was using it during her regular therapy sessions and her BCBA requested its availability during sessions. During comparison 1, the target items used for picture exchange were Smarties for Daphne, Ruffles chip for Alo, Smarties for Daniel, and Candy Corn for Walter. During comparison 2, M&M was targeted with Daniel and Smarties with Walter.

Speech Generating Device

During this condition, therapists placed the speech generating device with the opened Proloquo (Daphne, Daniel, Walter) or Visuals2Go (Alo) applications in front of the participant. The screen showed a page containing 10 icons, including the icon for the target mand, and all icons consisted of pictures of actual edibles (e.g., picture of a Puffed Corn). The placement of the icons within this array changed across trials in a nonsystematic manner. The correct response topography was touching the icon corresponding with the correct edible with enough force to generate audio in the device. In the first comparison, the target items used for the speech generating devices were gummies for Daphne, Puffed Corn for Alo, Starburst for Daniel, and Gummies for Walter. During the second comparison, Swedish Fish was targeted with Daniel and Sour Patch with Walter.

Manual Sign

During this condition, only the target edible was present on the table. The correct response topography was using a modified one-step manual sign from the American Sign Language to mand for the target edible. The target edibles assigned to the manual sign condition were Skittles for Daphne, Skittles for Alo, Candy Corn and Skittles for Daniel, and Starbursts and Nutter Butter for Walter. Thus, during the first mand modality comparison the manual sign taught for all participants (Daphne, Alo, Daniel, and Walter) was a modified version of the American Sign Language word for candy, which consisted of touching a cheek with one finger. During the second mand modality comparison, the manual sign taught to Walter was a modified version of the American Sign Language word for cookie (i.e., making an open circle with the right hand and using the tips of the fingers of the right hand to touch the palm of the left hand). For Daniel, the same manual sign (i.e., touching a cheek with one finger) was used during both mand training evaluations. The signs used during training were not in the participants’ repertoire prior to this study.

Phase III: Mand Modality Preference

Communication Modality Preference Assessment

Following mand training, participants’ preference for the communication modalities were evaluated. Preference was assessed using a concurrent chains arrangement (Hanley et al., 1997) in which all three modalities were available to the participants during all trials. Given that the AAC modality consisting of manual signs does not include a tangible item that can be presented to the participant, three picture cards with photos of the different modalities (e.g., photo of a picture card, photo of a speech generating device, photo of a manual sign) were used to represent each of the AAC modalities. These picture cards were used as initial links of the assessment. Following the selection of a picture card, the participant was provided with the chosen AAC device, if applicable, and an opportunity to mand for the item associated with that AAC modality during the mand training evaluation. Contingent on the participant emitting the correct response, reinforcement was provided. Prior to the onset of the assessment (i.e., choice trials) 10 forced-exposure trials for each of the AAC modalities were completed to pair each picture with the corresponding AAC modality. During the forced-exposure trials the therapists physically prompted the participants to select one of the pictures representing one of the communication modalities and then a mand trial of the corresponding AAC modality was completed. During the choice trials the participants were asked to choose one picture card (e.g., pick your favorite) and the therapist waited up to 30 s for the participants to make a selection. Each session consisted of 10 choice trials and 10 sessions were completed with each participant.

Results

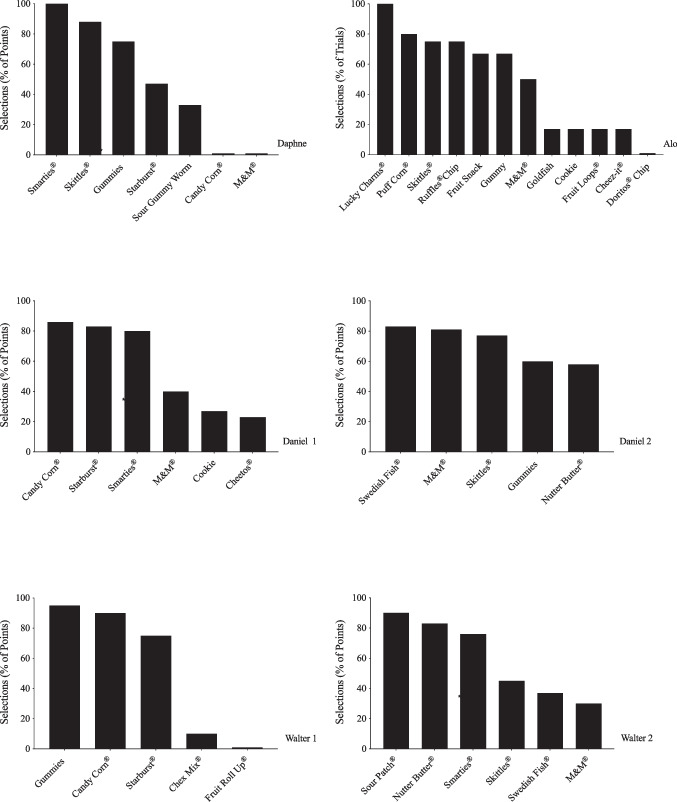

Results are shown in Figs. 1–4 and Table 2. Figure 1 depicts the results from the preference assessments conducted with all participants. Three highly preferred edibles for Daphne and Alo and six highly preferred edibles for Daniel and Walter were identified and used as targets during the mand training comparisons. For all participants, items that received at least 75% of possible points or were selected in at least 75% of the trials were defined as highly preferred.

Fig. 1.

Preference assessments

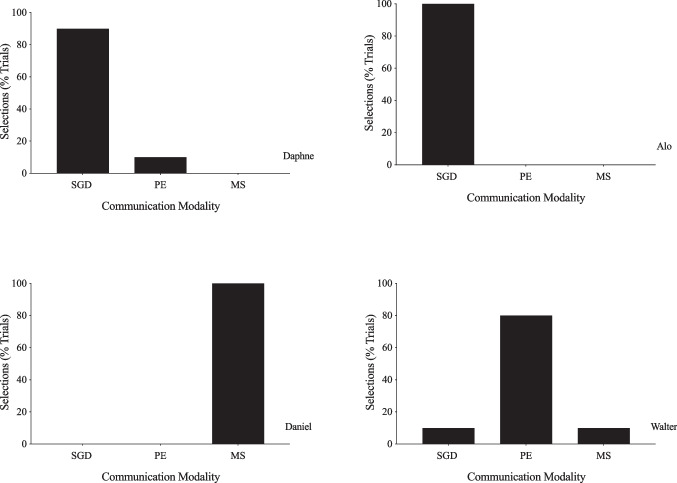

Fig. 4.

Results of the communication modality preference assessment. Note. SGD = Speech Generating Device; PE = Picture Exchange; MS = Manual Sign

Table 2.

Participants’ pre-training communication modality, EFL’s communication modality recommendation, and summary of results of skill acquisition and preference assessments

| Daphne | Alo | Daniel | Walter | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Training | PE | PE | PE | SGD |

| EFL Recommendation | MS | MS | MS | MS |

|

Faster Acquisition (C1 / C2) |

MS | SGD | SGD / SGD | SGD / SGD |

| Preferred Post-Training | SGD | SGD | MS | PE |

PE = Picture Exchange, MS = Manual Sign, SGD = Speech Generating Device,

C1 = Comparison 1; C2 = Comparison 2

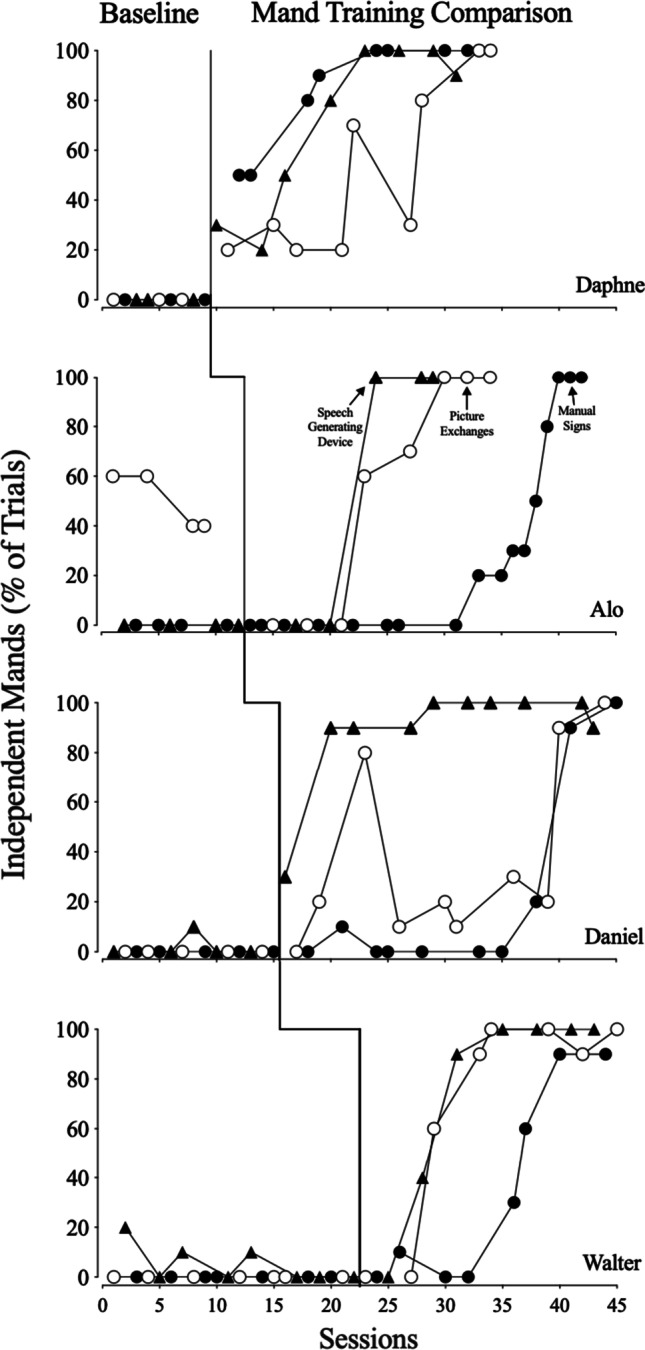

Figures 2 and 3 depict the results from the initial mand training comparison for all participants and the within participant replication for Daniel and Walter, respectively. During baseline phases, all participants engaged in zero to low levels of correct responding in all conditions except for Alo, who engaged in moderate levels of responding during the picture exchange condition. When mand training began, all participants acquired the mands with all communication modalities. Daphne required the least number of sessions to master the mand using manual sign whereas Alo acquired the mand using a speech generating device in fewer sessions. Across both comparisons Daniel and Walter required the least number of sessions to acquire the mands using the speech generating device.

Fig. 2.

First Mand training comparison

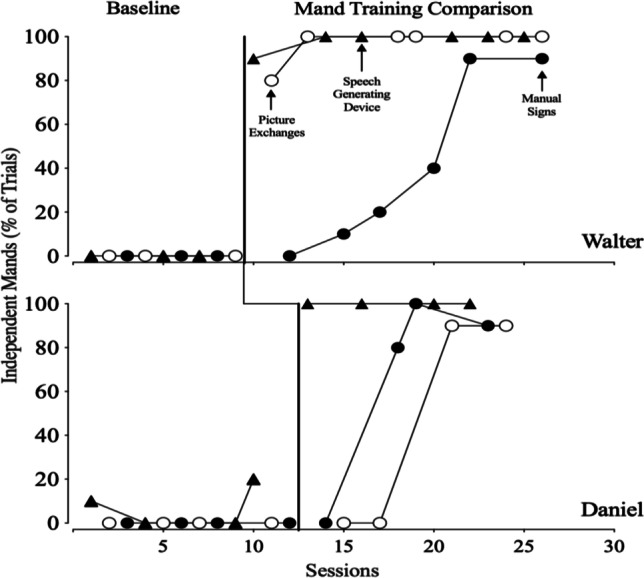

Fig. 3.

Second Mand training comparison

Figure 4 depicts the results from the communication modality preference assessment. Daphne and Alo showed preference for the speech generating device, Daniel showed preference for manual sign, and Walter showed preference for picture exchange. Table 2 summarizes the results of the study and depicts each participants’ pretraining communication modality, communication modality recommended by the EFL, fastest acquired communication modality during mand training comparisons, and the modalities participants preferred post-training. Overall, all participants acquired mands using the AAC modality recommended by the EFL. However, for all participants, rate of acquisition was similar across all three modalities of AAC and preference of AAC was idiosyncratic.

Discussion

This study extended prior research on the methods to select communication modalities for individuals with ASD and limited speech by assessing acquisition of mands across three communication modalities, one of which was identified using the EFL communication modality assessment. Prior to this study, Daphne, Alo, and Daniel were learning to use picture exchange and Walter was learning to use a speech generating device to communicate their wants and needs. Given that the EFL communication modality assessment recommended a form of manual signs for all four participants, acquisition of mands was compared across manual signs, picture exchange, and speech generating devices for all participants. Mands were acquired by all participants with the three AAC modalities suggesting that the EFL identified an appropriate communication modality for each of the participants. Although the EFL recommended manual signs for all participants, only one participant (Daphne) acquired manding in fewer sessions using this communication modality. Thus, based on our preliminary results, the likelihood of the EFL identifying the AAC modality associated with fastest acquisition remains unclear.

Although the AAC modality recommended by the EFL was not associated with greater rates of acquisition, it is important to note that all mands across the three AAC modalities evaluated were acquired in a similar number of sessions and that many variables can affect rate of acquisition (e.g., number of practice opportunities, teaching procedures employed, fluctuations in motivating operations). In addition, the EFL manual does not suggest that the AAC modality recommended by their assessment will be acquired more quickly than other modalities. Instead, it states that once an alternative modality of communication is selected, its effectiveness should be evaluated across a 2–3-month period during which the participant should have 200–300 opportunities per day to mand (see McGreevy et al., 2014, for additional information on evaluating effectiveness of the AAC). Moreover, for one of our participants, Alo, the top ranked AAC modality (i.e., writing words or drawing diagrams) was not age appropriate although it had the highest match and is associated with a large verbal community (i.e., large audience). Thus, it is likely that clinical judgment in addition to the recommendations of the EFL modality assessment should be considered. Given that all participants in the current study acquired the mand using the AAC modality recommended by the EFL, future research should evaluate whether rate of acquisition, maintenance, or generalization differs across AAC modalities when multiple mands are taught across differing AAC modalities. In addition, future research should assess the adequacy of the AAC modality recommended by the EFL throughout multiple years.

Previous studies that have evaluated acquisition of skills and/or preference across AAC modalities have either included a comparison of two commonly used modalities (e.g., picture exchange and speech generating device; Yong et al., 2021) or have evaluated modalities based on different factors. For example, Bryen et al. (1998) evaluated the use of sign language based on caregivers’ preferences and Jones et al. (1990) evaluated the use of multiple AAC modalities selected based on contextual characteristics (e.g., Jones et al., 1990). Therefore, the current study appears to be the first to assess the acquisition of mands using the communication modality recommended by the EFL Communication Modality Assessment.

Moreover, in this study, participants’ preference for the various AACs were also assessed. Daphne preferred the speech generating device but acquired manual sign first. Alo preferred the modality associated with the fastest acquisition of mands, speech generating device. Daniel preferred manual sign although he required the greatest number of sessions to master the mands taught using this modality. Walter preferred picture exchange even though he acquired mands faster with the speech generating device. These results are partially consistent with findings of previous studies. For instance, in Van der Meer et al. (2012) two of the four participants acquired the communication modality that they preferred in fewer sessions. Likewise, in Bock et al. (2005), two out of three participants who acquired mands using a Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS) in fewer sessions also preferred PECS over a speech generating device. However, because in the current study preference for one of the AACs was assessed after the mand comparisons were completed, commenting on whether preference is predictable of rate of acquisition is not possible. Moreover, given that chained responses were used in the mand preference assessment and not during mand training, it is possible that the results of the mand preference assessment are not accurate as the response effort to mand was increased in the preference assessments.

Despite the contributions to the literature, the current study has a few limitations. First, this study had four participants with similar characteristics and skills repertoires. Therefore, generality of the findings is limited to similar participants. Future researchers should extend this study by including participants of various ages and with varying skills. Another limitation of the study is that three out of four participants acquired all mands in similar number of sessions, thus conclusions about different rates of acquisition are limited. Perhaps future research should teach more complex mands as well as multiple mands across each communication modality. Moreover, although new mands were targeted during the mand training comparisons in all communication modalities used in the study, the participants in the study were learning to use picture exchange (Daphne, Alo, and Daniel) or a speech generating device (Walter) as their communication modality during their regular behavior therapy sessions prior to this study. Thus, it is possible that learning and reinforcement histories could have affected the rates of acquisition. Future research should evaluate rate of acquisition and preference across modalities with similar learning and reinforcement histories.

In addition, mand training included the initial question “What do you want?,” thus, it is possible that these mands were under control of this verbal stimulus. However previous research assessing acquisition of mands with or without the inclusion of the “What do you want?” prompt has not found a difference in rate of acquisition (Bowen et al., 2012). Furthermore, we did not assess whether the participants could discriminate amongst the nontarget pictures and icons available in the picture exchange arrays and the speech generating devices, respectively. Given that it is plausible that acquisition of a mand using a picture exchange or speech generating device is easier if the participant can discriminate amongst all other pictures or icons available, future research should assess the participants’ ability to discriminate across the nontarget pictures and icons and ensure that this variable is held constant across the two conditions (e.g., participants can discriminate across all pictures and icons; participants can discriminate across 50% of the pictures and icons).

Finally, in our attempt to control for difficulty level across modalities only a few aspects of the AAC devices and training format were addressed (i.e., number of responses required by the participant). Future research should also ensure that picture exchange and speech generating devices have the same number of icons displayed to the participant and ensure they contain the same icons. Moreover, for Daniel the same manual sign (touching a cheek with one finger for candy) was used for both mand training comparisons because most of the preferred items identified for him consisted of different types of candy. As shown by the baseline data for manual sign in Fig. 3, Daniel did not use the manual sign (candy) to request the candy targeted in this comparison (i.e., Skittles), suggesting that the mand acquired during the first comparison, which targeted Candy Corn, did not generalize to a novel stimulus. However, it is possible that the history of using that manual sign to request one candy may have facilitated, or perhaps hindered, acquisition of the mand for the second candy. Future research should ensure to target different manual signs across mand training evaluations.

In summary, the results of this study indicate that the EFL communication modality assessment is likely to identify an appropriate mode of communication; however, it is unclear whether this mode of communication will be acquired more quickly than other commonly used AACs. Moreover, although our study did not evaluate the impact of preference for AAC on acquisition because the preference assessments were completed only following the mand evaluation, our results are consistent with those of previous research, which demonstrated that preference may be idiosyncratic. Thus, clinicians must consider both, rate of acquisition and client’s preference, when prescribing an AAC modality for their clients. Finally, this study adds to the literature by evaluating a systematic method, the EFL communication modality assessment, clinicians may use to select a mode of communication for their clients.

Acknowledgements

Data for this study were collected by the first and fourth author in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the master of arts degree in applied behavior analysis and master of arts degree in professional behavior analysis, respectively. We thank Dr. Patrick McGreevy for his invaluable assistance and training on the use of the Essential for Living Communication Modality assessment.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Parental consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Bock, S. J., Stoner, J. B., Beck, A. R., Hanley, L., & Prochnow, J. (2005). Increasing functional communication in non-speaking preschool children: Comparison of PECS and VOCA. Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities, 40(3), 264–278. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23879720

- Bowen CN, Shillingsburg MA, Carr JE. The effects of the question “What do you want?” on mand training outcomes of children with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2012;45(4):833–838. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2012.45-833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryen, D. N., Goldman, A. S., & Quinslik-Gill, S. (1988). Sign Language with students with severe/profound mental retardation: How effective is it? Education & Training in Mental Retardation, 23(2), 129–137. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23878436

- Ciccone FJ, Graff RB, Ahearn WH. An alternate scoring method for the multiple stimulus without replacement preference assessment. Behavioral Interventions. 2005;20(2):121–127. doi: 10.1002/bin.177. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeLeon IG, Iwata BA. Evaluating of a multiple-stimulus presentation format for assessing reinforcer preferences. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1996;29(4):519–533. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1996.29-519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, W. W. Piazza, C. C., Bowman, L. G., & Amari, A. (1996). Integrating caregiver report with a systematic choice assessment to enhance reinforcer indentification. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 101(1), 15–25. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1996-01619-002 [PubMed]

- Fisher W, Piazza CC, Bowman LG, Hagopian LP, Owens JC, Slevin I. A comparison of two approaches for identifying reinforcers for persons with severe and profound disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1992;25(2):491–498. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1992.25-491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley GP, Piazza CC, Fisher WW, Contrucci SA, Maglieri KA. Evaluation of client preference for function-based treatment packages. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1997;30(3):459–473. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1997.30-459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones S, Jollef N, McConachie H, Wisbeach A. A model for assessment of children for augmentative communication systems. Child Language Teaching & Therapy. 1990;6(3):305–321. doi: 10.1177/026565909000600306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- LaRue RH, Pepa L, Delmolino L, Sloman KN, Fiske K, Hansford A, Weiss MJ. A brief assessment for selecting communication modalities for individuals with autism spectrum disorders. Evidence-Based Communication Assessment & Intervention. 2016;10(1):32–43. doi: 10.1080/17489539.2016.1204767. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McGreevy, P., Fry, T., & Cornwall, C. (2014). Essential for Living: A communication, behavior and functional skills assessment, curriculum and teaching manual for children and adults with moderate-to-severe disabilities. Patrick McGreevy.

- Ringdahl JE, Berg WK, Wacker DP, Ryan S, Ryan A, Crook K, Molony M. Further demonstrations of individual preference among mand modalities during functional communication training. Journal of Developmental & Physical Disabilities. 2016;28(6):905–917. doi: 10.1007/s10882-016-9518-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringdahl JE, Falcomata TS, Christensen TJ, Bass-Ringdahl SM, Lentz A, Dutt A, Schuh-Claus J. Evaluation of a pre-treatment assessment to select mand topographies for functional communication training. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2009;30(2):330–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sindelar, P. T., Rosenberg, M. S., & Wilson, R. J. (1985). An adapted alternating treatments design for instructional research. Education & Treatment of Children, 8(1), 67–76. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42898888

- Touchette PE, Howard JS. Errorless learning: Reinforcement contingencies and stimulus control transfer in delayed prompting. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1984;17(2):175–188. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1984.17-175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentino AL, LeBlanc LA, Veazey SE, Weaver LA, Raetz PB. Using a prerequisite skills assessment to identify optimal modalities for mand training. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2019;12(1):22–32. doi: 10.1007/s40617-018-0256-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Meer L, Sutherland D, O’Reilly MF, Lancioni GE, Sigafoos J. A further comparison of manual signing, picture exchange, and speech-generating devices as communication modes for children with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2012;6(4):1247–1257. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2012.04.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watson PJ, Workman EA. The non-concurrent multiple baseline across-individuals design: An extension of the traditional multiple baseline design. Journal of Behavior Therapy & Experimental Psychiatry. 1981;12(3):257–259. doi: 10.1016/0005-7916(81)90055-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yong YH, Dutt AS, Chen M, Yeong A, M. Evaluating acquisition, preference and discrimination in requesting skills between picture exchange and iPad®-based speech generating device across preschoolers. Child Language Teaching & Therapy. 2021;37(2):123–136. doi: 10.1177/0265659021989391. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.