Abstract

The Dengue Virus (DENV) non-structural protein 3 (NS3) is a multi-functional protein critical in the viral life cycle. The DENV NS3 is comprised of a serine protease domain and a helicase domain. The helicase domain itself acts as a molecular motor, either translocating in a unidirectional manner along single-stranded RNA or unwinding double-stranded RNA, processes fueled by the hydrolysis of nucleoside triphosphates. In this brief review, we summarize our contributions and ongoing efforts to uncover the thermodynamic and mechanistic functional properties of the DENV NS3 as an NTPase and helicase.

Keywords: NS3, Helicase, Molecular motors, Dengue

Introduction

The number of dengue cases reported to the World Health Organization (WHO) increased over 8-fold over the last two decades, from 505,430 cases in 2000, to over 2.4 million in 2010, and 5.2 million in 2019 (World Health Organization 2023). Reported deaths between the year 2000 and 2015 increased from 960 to 4032, affecting mostly younger age groups (Brady et al. 2012; Bhatt et al. 2013; Waggoner et al. 2016; Jentes et al. 2016). The total number of cases seemingly decreased during years 2020 and 2021, as well as for reported deaths. However, the data is not yet complete, and the COVID-19 pandemic might have also hampered case reporting in several countries (World Health Organization 2023).

The dengue virus (DENV) is a member of the family Flaviviridae, which includes other major public health concerns such as yellow fever virus, hepatitis C virus, and West Nile virus. Dengue virus exists in four distinct serotypes; all of them are mosquito-borne and cause dengue fever and dengue hemorrhagic fever/dengue shock syndrome (Gubler 2002). DENV non-structural protein 3 (NS3) is a multifunctional viral protein that is critical in the virus life cycle (Matusan et al. 2001), specifically implicated in viral replication, encapsidation, host immune evasion, and processing of the polyprotein precursor (Heaton et al. 2010; Perera and Kuhn 2008). NS3 is composed of 618 amino acids separated in two functional domains (Fig. 1A): an N-terminal domain (residues 1–167) that forms, together with residues of protein NS2B, an active serine protease and a C-terminal domain (residues 171-618) with RNA helicase, nucleoside 5’-triphosphatase (NTPase1), RNA 5’-triphosphatase, and RNA annealing activities (Li et al. 1999; Incicco et al. 2013; Gebhard et al. 2012; Cui et al. 1998; Bartelma and Padmanabhan 2002; Benarroch et al. 2004). These two functional domains may act independently of each other in vitro, and recombinant NS3 lacking the protease domain (NS3h) retains NTPase and helicase activities (Li et al. 1999; Gebhard et al. 2012).

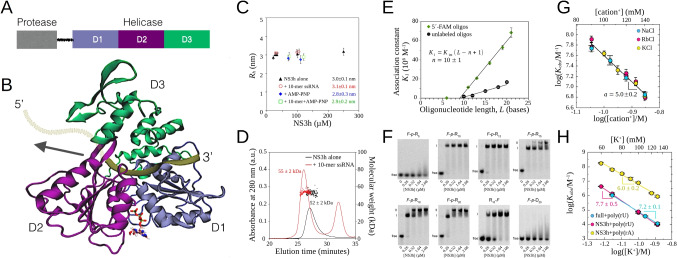

Fig. 1.

A Full-length NS3 domain and subdomain organization. Protease and helicase domains are connected by a flexible linker; helicase subdomains are labeled D1, D2, and D3. B Crystal structure (PDB 2jlv) of DENV NS3h with a 7-mer ssRNA bound (tan ribbon). NS3h subdomains are shown as ribbons and are colored as in A. Subdomains D1 and D2 present RecA-like folds and constitute the NTPase and motor core of the helicase. ATP is shown as sticks bound in the catalytic site (see Sarto et al. (2020)). The arrow represents the unidirectional translocation along ssRNA (5’ terminus of ssRNA drawn in for illustrative purpose). C The effective hydrodynamic radius () of DENV NS3h does not significantly change with its concentracion. values were obtained from pulsed field gradient-NMR experiments performed on the NS3h alone (black triangles), NS3h + 10-mer ssRNA (red circles), NS3h + AMP-PNP (blue diamonds), and NS3h + 10-mer ssRNA + AMP-PNP (green squares), in 10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.0), 100 mM KCl, 2.0 mM MgCl at 27 °C. D DENV NS3h is a monomer in solution. Size-exclusion chromatography elution profiles of NS3h alone (black solid line) and of a 1:2 mixture of NS3h and 10-mer ssRNA (red solid line) as monitored by the absorbance at 280 nm are shown (left axis). Molecular weights computed from 90° light scattering (right axis) are shown for the peak corresponding to elution of NS3h (black dots) and of the NS3h-RNA complex (red dots). Mean values (± standard error) of the corresponding molecular weights are 53 (± 2) kDa for NS3h alone and 55 (± 2) kDa for the NS3h-RNA complex. E Linear dependence of the macroscopic association constant on oligonucleotide length, both with (green series) or without (black series) fluorescent labeling, indicates that NS3h binds ssRNA in a non-specific manner. The NS3h binding site size is 10 (±1) nucleotides long. The association constant for the formation of a 1:1 complex, , was determined at pH 7.0, 30 °C, and 100 mM KCl. F Change in maximum NS3h-ssRNA stoichiometries evidenced with electrophoretic mobility shift assays of fluorescein-labeled oligonucleotides. Fluorescein-labeled oligonucleotides at 0.25 µM were incubated with NS3h at the indicated concentrations. Free oligonucleotides migrate rapidly to the bottom of the gels, while oligonucleotides bound to NS3h are retarded. A laser scanner was used to visualize the fluorescent samples in the gels. R are ssRNA oligos of n total bases, lacking the 5´-end phosphate, consisting in repetitions of AGUUG segments; F-p denotes the fluorescein label attached through phosphoramidite chemistry to the 5´ end. G The strong effect of monovalent salt concentration on NS3h-ssRNA binding affinity is independent of the nature of the cation. The association constant for the binding of DENV NS3h to the p-R oligo observed at each salt concentration, , is inversely proportional to the total concentration of monovalent cation (C+) raised to 5.0 ±0.2, suggesting the release of 5 monovalent cations upon formation of the NS3h-RNA oligo complex. Measurements were performed at pH 6.5 and 25 °C. H Binding of DENV NS3 to polyrribonucleotides. Sensitivity to salt concentration is independent of the presence of the protease domain in the full length NS3 protein (NS3f). Measurementes were performed at pH 6.5 and 25 °C. For further experimental details, see Gebhard et al. (2014) (C–F) and Cababie et al. (2019) (G–H).

The DENV NS3h belongs to the DExH-box subgroup of superfamily 2 (SF2) helicases and was shown to unwind double-stranded RNA (Li et al. 1999). It is structurally organized in three subdomains (Fig. 1 A, B); the core of the molecular motor is comprised of two RecA-like domains (D1 and D2), present in all helicases, which form the NTP-binding cleft on one side and an RNA-binding interface on the opposite side (Ye et al. 2004; Liao 2011). A third sub-domain (D3), unique to this subgroup, further secures ssRNA (Fig. 1B). Domains D1 and D2 are RecA-like domains conserved among SF1 and SF2 helicases, including the DEAD-box helicases, whereas D3 is unique to this class of helicases. The DENV NS3h has been crystallized both in presence and absence of ssRNA, in various nucleotide-binding conditions (Luo et al. 2008b). Given that a 3’-single-stranded overhang is required by DENV NS3h to display its helicase activity, it was classified as 3’ 5’ helicase (Wang et al. 2009). RNA helicases are ubiquitous proteins and participate in virtually all processes of the RNA metabolism (Jankowsky 2011). Many viruses encode proteins with in vitro helicase activity, and their specific roles in viral replication are still a topic of research.

Helicases are NTPase proteins that bind to nucleic acids and couple the exergonic reaction of NTP hydrolysis to the production of mechanical work through a sequence of conformational and binding transitions that result in the unidirectional translocation along the nucleic acid and the unwinding of doubled strand helices (Lohman et al. 2008). A current hypothesis to explain such coupling is that successive energy states (conformational states) during the hydrolysis of NTPs in the protein catalytic site propagate through the protein structure producing the mechanical movements of translocation at the nucleic acid binding site. A molecular description of the transduction mechanism requires identifying and characterizing all intermediate states of both the NTPase and the mechanical work production cycles as well as establishing the synchronization between phases of the mechanical movement and each step of the catalytic cycle.

A great deal of work has been done to probe the mechanochemical coupling of the helicase and NTPase activities of DEAD-box and DExH-box RNA helicases. In terms of their RNA unwinding mechanisms, the two groups have been distinguished as non-processive and processive helicases, respectively (Pyle 2008). Nevertheless, a large part of our understanding of the DExH-box helicases comes from the widely studied NS3h of the hepatitis C virus (HCV). Care must be taken when comparing the mechanistic aspects even within this subgroup. For instance, HCV NS3 has been shown to bind efficiently to both ssDNA and ssRNA, although tighter to the former, whereas DENV NS3 displays a high selectivity for ssRNA substrates (Levin and Patel 2002; Wang et al. 2009; Gebhard et al. 2014). Accordingly, while both helicases need a 3´ single-stranded overhang on the nucleic acid for efficient unwinding of double-stranded substrates, DENV requires the loading strand to be RNA for efficient unwinding, regardless of the displaced strand, whereas HCV NS3 unwinds efficiently on substrates with both DNA and RNA loading strands, although with higher processivity on DNA (Wang et al. 2009; Pang et al. 2002). The presence or absence of nucleotide analogs, rather than the presence or absence of RNA, results in large domain movements in crystal structures of the HCV NS3h, whereas the opposite trend (and different domain movements entirely) has been observed for the DENV NS3h (Kim et al. 1998; Luo et al. 2008b). Moreover, the conserved “gatekeeper” tryptophan residue in D3 of the HCV NS3h, which is proposed to be key in its spring loaded translocation mechanism (Pyle 2008), is not present in any of the DENV NS3h sequences. Further thermodynamic and kinetic studies of helicases in this subgroup will be instrumental in clarifying the hallmark mechanistic aspects.

In what follows, we will present the advances in research from our laboratories on the thermodynamics and molecular mechanism of the interaction with nucleic acids and the functional properties of the DENV NS3.

DENV NS3h is a monomeric protein in solution with molecular weight of 53 kDa

Knowing the self-assembly properties of a helicase in solution, in the absence and presence of interacting substrates, is essential to correctly interpret equilibrium and kinetic experiments performed to elucidate the mechanism of its enzymatic, translocase, and helicase activities (Lohman et al. 2008; Henn et al. 2012a; Gebhard et al. 2014).

Crystallographic studies (Xu et al. 2005) and small angle X-ray scattering measurements (Luo et al. 2008a) have both indicated that the DENV NS3 protein is monomeric. In this sense, we were interested in determining the oligomeric state of NS3 when the protein interacts in solution with ligands that participate in both the NTPase catalytic cycle as well as the translocation and unwinding activities.

Pulsed field gradient-nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (PFG-NMR) and size exclusion chromatography coupled with static light scattering (SEC-SLS) techniques were used to determine, respectively, the hydrodynamic radius () and the average molecular weight (MW) of NS3h in solution to investigate possible protein self-assembly (Gebhard et al. 2014).

Mean values of obtained in the presence of a 10-mer single-stranded RNA oligonucleotide lacking the 5´ phosphate (R) and/or ATP analog AMP-PNP were (i) 3.0 (± 0.1) nm for NS3h alone, (ii) 3.1 (± 0.1) nm for NS3h in the presence of R, (iii) 2.8 (± 0.3) nm for NS3h in the presence of AMP-PNP, and (iv) 2.9 (± 0.2) nm for NS3h in the presence of both R and AMP-PNP (Fig. 1C).

SEC-SLS experiments were performed on free NS3h and NS3h-ssRNA complexes. Analysis of the elution profiles indicated the presence of a single aggregation state of NS3h with a unique MW: 53 (± 2) kDa for free NS3h and 55 (± 2) kDa for the complex with the R oligonucleotide (Fig. 1D).

We compared the values with those expected for a globular folded protein considering only the number of amino acid residues (Eq. (3) in Marsh and Forman-Kay (2010)), which are 2.84 nm for a monomer (469 residues) and 3.46 nm for a dimer. In addition, keeping in mind the theoretical values of MW expected for a NS3h monomer (53.4 kDa for free NS3h and 56.6 kDa for the complex), we concluded that the NS3h protein is a monomer even in the presence of an ATP analog and of short ssRNA, and this oligomeric state does not change even at protein concentrations as high as 250 M (Gebhard et al. 2014).

NS3h binds ssRNA in a non-specific manner with a binding site size of 10 nucleotides

Early research on DENV NS3 provided clear biochemical evidence that it preferentially binds to single-stranded RNA, in comparison to double-stranded nucleic acids and to DNA, and that the extent of binding is strongly dependent on salt concentration (Wang et al. 2009). Crystallographic studies supported these conclusions with the observation that the nucleic acid binding cleft resolved in the X-ray diffraction data was wide enough to accommodate a single strand of RNA and not a duplex and that the complex presented abundant ionic interactions between lysine and arginine side chains and phosphate groups on the nucleic acid backbone (Xu et al. 2005; Luo et al. 2008a; Xu et al. 2005; Cababie et al. 2019). In addition, crystallographic data revealed the polarity of the NS3-ssRNA interaction—with the RecA-like domains 1 and 2 located on the 3´ and 5´ sides, respectively, of the RNA segment (Fig. 1B)—and provided a first estimation of the binding site size, with the finding that a stretch of 7 nucleotide residues were resolved from X-ray diffraction data (Xu et al. 2005).

Quantitative thermodynamic information on the binding site size, intrinsic affinities, and cooperativity was later obtained by our group through model-independent analysis of fluorescence titrations with oligonucleotides of different lengths and sequences (Lohman and Bujalowski 1991; Gebhard et al. 2014). We observed that the maximum binding density of NS3h molecules on fluorescein-labeled oligonucleotides switches from 1 to 2 when increasing the length of the oligos from 15 to 18 nt., and this observation was independently verified through electrophoretic mobility shift assays (Fig. 1 E, F) (Gebhard et al. 2014).

Values of the macroscopic association constant for the formation of 1:1 complexes with oligonucleotides of different lengths (Fig. 1E) provided two critical thermodynamic properties of the interaction of NS3h and ssRNA: it can be described as a non-specific protein-nucleic acid interaction with multiple identical and overlapped binding sites along the RNA, with a single intrinsic association constant (), and it involves a minimum binding site size of 9-10 nt. on the RNA to establish all relevant contacts with the protein. It fits the overall behavior dictated by the statistical thermodynamics formalism of Epstein for the binding of large ligands to one-dimensional lattices (Epstein 1978). These observations were corroborated both with 5´-labeled oligonucleotides as well as with unlabeled oligos through competition titration experiments (Fig. 1E).

Additional competition binding experiments performed with unlabeled poly(rA) and analyzed according to the formalism of McGhee and von Hippel (1974) provided us with an estimate of the occluded site size of NS3h on the RNA, with a value of 10–11 nt., in accordance with a previous estimate based on the modulation of ATPase activity by polyrribonucleotides (Incicco et al. 2013).

Model-independent analysis of fluorescence titrations and the McGhee-von Hippel formalism for the analysis of competition titrations with poly(rA) also allowed us to quantify the cooperativity established between protein molecules bound to the same RNA strand, which, in the experimental conditions tested (pH 7.0, 30 °C, 100 mM KCl), was characterized by a 10-fold increase in affinity for nearest neighbor binding sites ( 10 (Gebhard et al. 2014)).

As mentioned above, binding of DENV NS3 to ssRNA is strongly affected by salt concentration. We systematically investigated the effect of salts on binding affinity and found that binding of NS3h or full length NS3 to ssRNA is accompanied by the release of 5–7 monovalent cations from the nucleic acid—independently of the nature of the cation, of the presence of the protease domain and of the presence of the fluorescein label on the RNA—which contributes positively to the entropy of binding (Fig. 1 G, H). In terms of the theory developed by Record et al. (1978); Mascotti and Lohman (1992), DENV NS3h behaves as an oligocation that effectively neutralizes 10 phosphate groups upon binding to ssRNA (Cababie et al. 2019; Cababie 2018).

Nucleoside triphosphate substrates of the NTPase and helicase activities of DENV NS3

DENV NS3 catalyzes the hydrolysis of the -phosphate from canonical nucleoside triphosphates ATP, CTP, GTP, and UTP, and all four NTPs are efficient substrates to fuel RNA unwinding (Fig. 2A) (Cui et al. 1998; Li et al. 1999; Gebhard et al. 2012). Through competition experiments in which two substrates were simultaneously present in the reaction media, we obtained kinetic evidence that all four NTPs are hydrolyzed in the same catalytic site of the NS3 (Fig. 2B) (Incicco et al. 2013).

Fig. 2.

A Representative gels of RNA unwinding time courses of DENV NS3. Different nucleotides were tested as substrates for the RNA unwinding activity of full-length NS3 (NS3f) and its helicase domain (NS3h). Unwinding reactions were carried out at 37 °C with 250 nM of enzyme and 5 nM of dsRNA substrate. Reactions were initiated by addition of 2.0 mM of ATP, CTP, GTP, or UTP together with a ssRNA trap and terminated at the indicated times. The duplex RNA substrate contained a 15 nt. long 3´ single-stranded overhang followed by a 15 bp. double-stranded segment. Adapted from Gebhard et al. (2012). B ATP, CTP, GTP, and UTP compete for the same catalytic site. Competition plots for ATP and a second nucleotide. Initial rates of phosphate release () were measured in reaction mixtures containing two nucleotides at a time. As the value of abscissa x goes from 0 to 1, the concentrations of both substrates changes concomitantly according to [ATP]x[ATP] and [NTP](1-x)[NTP]. and values obtained from substrate curves were used to simulate the prediction of the single-active-site model (continuous line) and the two-independent-active-sites model (dashed line). For details see Incicco et al. (2013). C Modulation of DENV NS3h ATPase activity by poly(rA). NS3h and RNA were pre-incubated in the reaction media prior to the addition of ATP. Final NS3h concentration was 10 nM. Continuous lines are simulations of the two states model fitted to the results. The model involves inactive NS3h when bound to sites on the RNA surrounded by other NS3 molecules. For details, see Incicco et al. (2013). D Steady-state product inhibition studies indicates an ordered product release mechanism for the DENV NS3 catalytic cycle of NTP hydrolysis. Effect of ADP concentration on the initial rates of ATP hydrolysis (vi) determined at the indicated concentrations of ATP, in the absence (circles) and in presence of orthophosphate (P, squares). P concentration was 20 mM in presence of 0.25 mM and 1 mM ATP and 10 mM in presence of 0.050 mM ATP. Lines are simulations of a kinetic scheme with ordered product release, being P the first released substrate. This model provided the better description of all the results and supports the results obtained from computational free energy calculations (see Fig. 3). For details, see Adler et al. (2022)

The degree of specificity of DENV NS3 for different NTPs was partially assessed in some studies (Li et al. 1999; Bartelma and Padmanabhan 2002; Benarroch et al. 2004; Fucito 2008; Perera and Kuhn 2008; Sampath et al. 2006; Gebhard et al. 2014). To evaluate this property systematically under identical conditions, we made use of the fact that steady-state rates of NTP hydrolysis displayed hyperbolic substrate curves—characterized by parameters and (Benarroch et al. 2004; Fucito 2008; Incicco et al. 2013; Cababie 2018). The ratio between these parameters, , which is given the name specificity constant (Cornish-Bowden 2014), quantifies the apparent second-order rate constant for the conversion of free enzyme plus substrate to free enzyme plus products under steady-state conditions, and the ratio of the values of for two different substrates competing for the same catalytic site is equal to the ratio of steady-state rates at which these two substrates are being transformed into products when they are both present and at the same concentration (Cornish-Bowden 2014).

We found that, in the absence of RNA, both the full length and the isolated helicase domain of NS3 show poor specificity among these nucleotides (Table 1), with values differing in less than an order of magnitude, showing a slight preference for purine nucleotides. Interestingly, in the presence of a saturating concentration of poly(rA) (as tested at 1 mM ATP), DENV NS3 displayed a more defined preference for purine NTPs, ATP, and GTP, with values around an order of magnitude higher than for pyrimidine NTPs, CTP, and UTP (Table 1) (Cababie 2018).

Table 1.

Nucleotide specificity ()/ M

| NTP | NS3f () | NS3h () | NS3h + RNA () |

|---|---|---|---|

| ATP | 9.6 ± 0.6 | 160 ± 10 | 101 ± 27 |

| GTP | 11 ± 1 | 210 ± 30 | 123 ± 38 |

| CTP | 9.6 ± 0.5 | 100 ± 10 | 21 ± 4 |

| UTP | 3.5 ± 0.9 | 62 ± 6 | 10 ± 3 |

The ability of DENV NS3 to employ ATP, GTP, CTP, and UTP as substrates of its NTPase and helicase activities constitutes another example of substrate promiscuity in the DExH box family of SF2 helicases (Fairman-Williams et al. 2010; Das et al. 2014; Belon and Frick 2009). It is in accordance with the observation from crystallographic studies that the ribose and base moieties of ATP analogs bound to the protein might be exposed to the solvent, whereas the triphosphate appears to be buried between the RecA-like motor domains (Sampath et al. 2006) and could be associated with the lack of a conserved Q motif in DExH NS3 helicases, which appears to mediate contacts with the adenine base of ATP in the more specific DEAD-box helicases (Fairman-Williams et al. 2010; Tanner et al. 2003).

A general conclusion that can be drawn from the literature is that nucleic acids stimulate NTPase activity of helicases (Matson and Kaiser-Rogers 1990; Matson 1991; Lohman and Bjornson 1996; Jankowsky and Fairman 2007; Henn et al. 2012b; Jarmoskaite and Russell 2014). Our steady-state kinetic studies on the DENV NS3h showed that the value of the catalytic constant at saturating ssRNA is about ten times greater than in the absence of RNA (with values of 2.91±0.03 in absence of RNA and 28±1 and 16±1 at saturating concentrations of poly(rA) and poly(rC), respectively, at 25 °C, pH 6.5, 20 mM KCl, see Incicco et al. (2013)). The effect of RNA on the ATPase activity, however, was non monotonous at low ATP concentrations (Fig. 2C). Similar observations have been reported in the literature for other helicases, where it has been observed inhibition by nucleic acids at low ATP concentrations (Porter 1998), as well as non-monotonous dependencies of ATPase activity with nucleic acid concentration (Wong et al. 1996). In the search for a kinetic model to describe this observations, we tested the general modifier model of Jean Botts and Manuel Morales, since it is able to give rise to inhibition by an activator at low substrate concentrations as well as a non monotonous dependence of enzymatic activity on modifier concentration (Botts and Morales 1953; Botts 1958; London 1968), and found that it was not able to explain our results (Incicco et al. 2013). Inspired by the observation that inhibition was concomitant with the expected increase and decrease of the fraction of NS3 bound to RNA with high binding densities, we hypothesized that inhibition at low bases/NS3 ratios was the result of crowding of NS3 molecules along the RNA lattices and that NS3 bound to a given RNA strand affects the activity of other NS3 molecules bound to adjacent sites in the same strand (Incicco et al. 2013). Employing the formalism of McGhee and von Hippel for the binding of large ligands to one-dimensional lattices of infinite length (McGhee and von Hippel 1974), we tested a kinetic scheme involving activation of NS3 when bound to RNA away from other proteins and total inhibition when surrounded by other NS3 molecules. The model was able to account for the results and provided a first estimate of the occluded site size of NS3h interacting with ssRNA, as previously discussed.

Conformational changes during the catalytic cycle of ATP hydrolysis

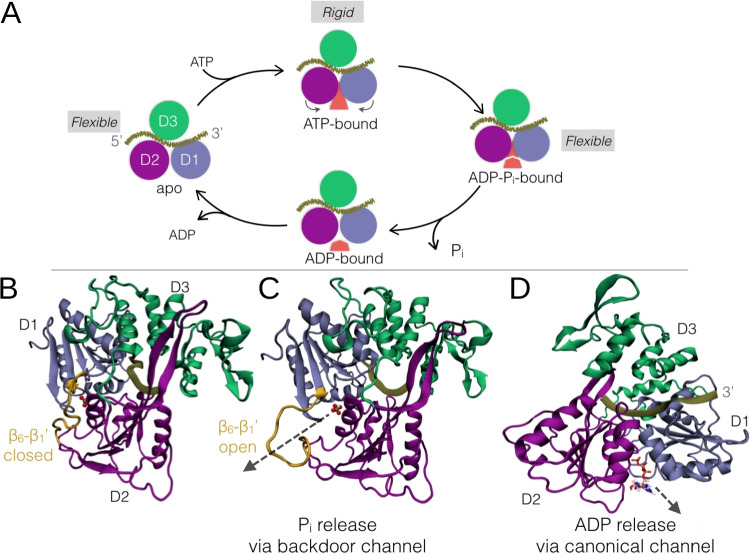

The transduction of energy from the catalytic site to the RNA binding site of NS3 corresponds to differences in the conformational ensemble accessible to the protein-RNA complex during the catalytic cycle (Fig. 3). Crystallographic studies of NS3h with and without ATP analogs, transition state analogs, as well as with ADP and P, in presence and absence of RNA, serve as conformational snapshots of the catalytic cycle of the enzyme-catalyzed hydrolysis of ATP. Indeed, crystal structures of NS3h in absence and presence of RNA highlight key changes in the catalytic site that are likely related to the RNA-induced stimulation of ATPase activity (Luo et al. 2008b). Nevertheless, the crystal structures with bound RNA and different occupancy of the catalytic site do not lead to a mechanistic hypothesis as to how the catalytic cycle of ATP hydrolysis is coupled to the translocation and unwinding work done by NS3h. This is in contrast to the structurally related HCV NS3 helicase, for which large domain movements resulting from ATP binding and hydrolysis offer mechanistic insight into the translocation along RNA (Appleby et al. 2011).

Fig. 3.

A Catalytic cycle for ATP hydrolysis in NS3 with ordered product release stages, highlighting the flexible-rigid-flexible protein dynamics observed for the apo, ATP-bound, and product-bound stages, respectively. Adapted from Adler et al. (2022). B Closed and C open conformations of the loop gating the backdoor channel for phosphate release. NS3h is shown rotated 90° with respect to Fig. 1B. Pi is shown as balls and sticks bound to the protein in the catalytic site and the arrow is pointing through the backdoor channel. D ADP release via the canonical channel is indicated with an arrow, with NS3h shown in the same orientation as in Fig. 1B. Subdomains are shown as ribbons, colored as in Fig. 1, with the loop (residues 318 to 331) colored in yellow

Molecular dynamics simulations of NS3h (bound to the crystallographic 7-mer ssRNA) have been carried out by our groups and others in order to further elucidate the mechanism through which the catalytic and mechanical activities are coupled (Sarto et al. 2020; Davidson et al. 2018; Du Pont et al. 2022).

We have observed that though the average conformation of NS3h is unchanged due to the presence of ATP or the products of hydrolysis, the overall flexibility of the protein backbone is greater in the apo and product-bound states than in the presence of ATP. As part of this increased flexibility, we have observed a novel conformation of the DENV NS3h, in which the loop, which connects domains D1 and D2—spanning the stretch of amino acid residues from the end of the strand in D1 to the beginning of the strand in D2—separates from the catalytic site and the D1–D2 interface (Fig. 3). The opening of the loop creates a backdoor channel to the catalytic site, which plays a key role in the product-release stages of the catalytic cycle, as we describe in “Mechanism of product release from the catalytic cycle of ATP hydrolysis”.

In addition to the flexible-rigid-flexible dynamics observed for the apo, ATP-bound, and product-bound states, we have also observed an asymmetry in the per-nucleotide root mean squared fluctuations of the bound RNA, such that the 3’ terminus fluctuates more than the 5’ terminus, which is a likely entropic driving force in the 3’-to-5’ translocation and unwinding mechanism. Aside from this change in flexibility, simulations thus far of the DENV NS3h bound to the crystallographic 7-mer do not appear to capture the expected allosteric change in RNA binding due to differential occupancy of the catalytic site, and it is likely that the presence of longer ssRNA oligos are necessary to observe this effect (see “Work in progress and future directions”).

Mechanism of product release from the catalytic cycle of ATP hydrolysis

The study of the mechanism of product release upon the hydrolysis of NTPs is important not only for elucidating the sequence of reactions in the catalytic cycle of NS3, but also because it is known that phosphate release triggers functional conformational changes in a variety of systems, from cytoskeletal motor proteins (Gilbert et al. 1995) to translocating helicases (Wang et al. 2010), and sets the stage for elucidation of the mechanochemical coupling mechanism employed by RNA helicases. As a contribution to the general study of the energy transduction process of the DENV NS3 helicase, we determined the mechanism of product release from the catalytic cycle of ATP hydrolysis (Adler et al. 2022).

Based on steady-state ATPase activity determinations in the presence of different initial concentrations of ADP and/or P, we tested five general kinetic mechanisms of product release for uni-bi enzymatic reactions (Fig. 2D). We established that the pathway of the catalytic cycle of ATP hydrolysis by NS3h proceeds through an apparent Uni-Bi ordered sequential mechanism that includes a ternary complex intermediate (NS3h-P-ADP) that evolves releasing the first product, P, and subsequently ADP (Fig. 3A) (Adler et al. 2022).

We reached this same conclusion by following a completely different and independent approach that provided new insights into the molecular mechanism of product release. We performed steered molecular dynamics (sMD) simulations to construct free energy profiles corresponding to the initial release of P and ADP from the catalytic site via specific pathways. In particular, we evaluated the initial release of each species from the crystallographic (closed-loop) conformation of NS3h (Fig. 3B). In this conformation, there is only one apparent channel connecting the catalytic site with the solvent, and we refer to this channel as the canonical channel (Fig. 3B). Though the P molecule is buried behind the ADP molecule in the catalytic site, and thus its release prior to that of ADP would seem unlikely, we found that not only is the P molecule able to exit via the canonical channel even with ADP still bound, but that this process is actually less costly than the initial release of ADP (Adler et al. 2022). Nevertheless, we found the initial release of either ADP or P via the canonical channel to be very endergonic, and neither free energy profile was compatible with the experimentally fitted turnover number. When considering, however, the open conformation of the - loop (Fig. 3C), we found P release via the open backdoor channel to be an exergonic process, with a barrier height compatible with the experimentally fitted turnover number. We further found that the open-loop conformation also favors the subsequent dissociation of ADP via the canonical channel (Fig. 3D) (Adler et al. 2022). The opening of the - loop, which results in the hydration of the catalytic site, appears to be key in the product release mechanism.

There are reasons to think that this conformational change is possibly shared by other SF2 helicases. Structures of flaviviral NS3 helicases deposited into the Protein Data Bank, which include dengue serotypes 2 and 4, Zika, yellow fever, Kunjin, Kokobera, and Murray Valley encephalitis viruses, in varying conditions (with or without the protease domain, bound to RNA, and/or nucleotide mimics) have all been resolved with the - loop in a similar closed conformation (SI Fig. 3 of Sarto et al. (2020)). The sequence of this loop, which comprises the 15 amino acids downstream of motif III connecting domain D1 with D2, is largely conserved among these NS3 helicases as well (67%, SI Fig. 4 of Sarto et al. (2020)). Interestingly, beyond DExH helicases, motif III itself has been proposed to be key in coupling the ATPase and RNA helicase activities in DEAD-box helicases and conformational changes of the - loop necessarily impact this tripeptide motif (Henn et al. 2012b). More recently, the same molecular mechanism of phosphate release has been proposed for the DEAD-box eIF4AI helicase, where the - loop was found to gate the formation of a backdoor channel that favors P release (Lu et al. 2015). Taken together, these observations make the targeting of the closed-to-open conformational equilibrium (Fig. 3 B and C) a promising approach in the rational design of non-competitive NS3 inhibitors.

Work in progress and future directions

We are now investigating the mechanical cycles of RNA translocation and unwinding by DENV NS3 using single-molecule force-distance measurements. Thanks to the generosity of Dr. Carlos Bustamante, we have carried out such experiments employing optical tweezers in the Bustamante lab at the University of California (Berkeley, CA, USA). Preliminary analysis suggests that unwinding by DENV NS3 takes place in steps and sub-steps, which together can be described by an inchworm mechanism. We have also observed that dwell times and NS3 dissociation probability increase when tandem arrangements of GC base pairs are incorporated into the dsRNA sequence. This finding orients a future project: to determine how the local stability of dsRNA affects the processivity as well as the unwinding and translocation functionalities of NS3.

Future directions also include the study of the sequence of reactions of the catalytic cycle of ATP hydrolysis and the role of RNA in this mechanism using pre-steady-state single turnover kinetics experiments and hybrid quantum mechanical-molecular mechanical (QM/MM) simulations, to integrate with the knowledge of the ordered product release thus far established.

Open questions still arise when connecting the available atomistic structural information to the thermodynamic and functional properties of the DENV NS3h, namely regarding the allosteric effect of the occupancy of the catalytic site on the interaction between the DENV NS3h and ssRNA. We are currently evaluating, using atomistic models, how this interaction and the dynamics of the NS3h-ssRNA complex are affected by the presence of longer ssRNA oligonucleotides.

These directions, currently underway, and much more future work are needed to closely understand how this motor protein operates as an energy transducer.

Acknowledgements

We thank Andrea V. Gamarnik, Dario A. Estrin, Leopoldo G. Gebhard and Rodolfo M. González-Lebrero for their continued support and fruitful discussions throughout these projects.

Author Contributions

SBK and MA contributed to the scope and structure of the review article. The first draft of the manuscript was written by JJI, MA, and SBK, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Agencia Nacional de Promoción de la Investigación, el Desarrollo Tecnológico y la Innovación (Agencia I+D+i, Argentina) Award Numbers PICT 2020-3445 and PICT-2021-I-INVI-00854, and by the Universidad de Buenos Aires (UBA, Argentina), UBACYT 20020170100730BA.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable

Code Availability

Not applicable

Declarations

Ethical approval

Not applicable

Consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Throughout the text, we refer to the NTPase activity of NS3h when we wish to refer to its broader enzymatic activity and ATPase activity when the discussion specifically pertains to its activity with ATP as a substrate.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

J. Jeremías Incicco, Email: jjincicco@ffyb.uba.ar.

Mehrnoosh Arrar, Email: marrar@ic.fcen.uba.ar.

Sergio B. Kaufman, Email: sbkauf@qb.ffyb.uba.ar

References

- Adler NS, Cababie LA, Sarto C, Cavasotto CN, Gebhard LG, Estrin DA, Gamarnik AV, Arrar M, Kaufman SB. Insights into the product release mechanism of dengue virus NS3 helicase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022;50(12):6968–6979. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkac473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appleby TC, Anderson R, Fedorova O, Pyle AM, Wang R, Liu X, Brendza KM, Somoza JR (2011) Visualizing ATP-dependent RNA translocation by the NS3 helicase from HCV. J Mol Biol 405(5):1139–1153. ISSN 0022-2836. 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.11.034. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022283610012647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bartelma G, Padmanabhan R. Expression, purification, and characterization of the RNA 5’-triphosphatase activity of dengue virus type 2 nonstructural protein 3. Virology. 2002;299(1):122–132. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belon CA, Frick DN. Fuel specificity of the hepatitis C virus NS3 helicase. J Mol Biol. 2009;388(4):851–864. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.03.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benarroch D, Selisko B, Locatelli GA, Maga G, Romette J-L, Canard B. The RNA helicase, nucleotide 5’-triphosphatase, and RNA 5’-triphosphatase activities of dengue virus protein NS3 are Mg2+-dependent and require a functional Walker B motif in the helicase catalytic core. Virology. 2004;328(2):208–218. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt S, Gething PW, Brady OJ, Messina JP, Farlow AW, Moyes CL, Drake JM, Brownstein JS, Hoen AG, Sankoh O, et al. The global distribution and burden of dengue. Nature. 2013;496(7446):504–507. doi: 10.1038/nature12060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botts J. Typical behaviour of some simple models of enzyme action. Trans Faraday Soc. 1958;54:593–604. doi: 10.1039/TF9585400593. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Botts J, Morales M. Analytical description of the effects of modifiers and of enzyme multivalency upon the steady state catalyzed reaction rate. Trans Faraday Soc. 1953;49:696–707. doi: 10.1039/TF9534900696. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brady OJ, Gething PW, Bhatt S, Messina JP, Brownstein JS, Hoen AG, Moyes CL, Farlow AW, Scott TW, Hay SI. Refining the global spatial limits of dengue virus transmission by evidence-based consensus. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cababie LA (2018) Caracterización termodinámica de los múltiples equilibrios químicos involucrados en la interacción entre la proteína NS3 helicasa del virus del dengue y oligonucleótidos de ARN (Thermodynamic characterization of the multiple chemical equilibria involved in the interaction of dengue virus NS3 helicase and RNA oligonucleotides). Ph.D. thesis, Universidad de Buenos Aires. Facultad de Farmacia y Bioquímica. Universidad de Buenos Aires, Argentina. Document available under request

- Cababie LA, Incicco JJ, González-Lebrero RM, Roman EA, Gebhard LG, Gamarnik AV, Kaufman SB. Thermodynamic study of the effect of ions on the interaction between dengue virus NS3 helicase and single stranded RNA. Scientific Reports. 2019;9(1):10569. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-46741-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornish-Bowden A. Fundamentals of enzyme kinetics, chapter 2. Elsevier Science; 2014. pp. 33–39. [Google Scholar]

- Cui T, Sugrue RJ, Xu Q, Lee AKW, Chan Y-C, Fu J. Recombinant dengue virus type 1 NS3 protein exhibits specific viral RNA binding and NTPase activity regulated by the ns5 protein. Virology. 1998;246(2):409–417. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das PK, Merits A, Lulla A. Functional cross-talk between distant domains of chikungunya virus non-structural protein 2 is decisive for its RNA-modulating activity. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(9):5635–5653. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m113.503433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson RB, Hendrix J, Geiss BJ, McCullagh M. Allostery in the dengue virus NS3 helicase: insights into the NTPase cycle from molecular simulations. PLoS Comput Biol. 2018;14(4):e1006103. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Pont KE, McCullagh M, Geiss BJ. Conserved motifs in the flavivirus NS3 RNA helicase enzyme. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: RNA. 2022;13(2):e1688. doi: 10.1002/wrna.1688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein IR (1978) Cooperative and non-cooperative binding of large ligands to a finite one-dimensional lattice: a model for ligand-ougonucleotide interactions. Biophys Chem 8(4):327–339. ISSN 0301-4622. 10.1016/0301-4622(78)80015-5.https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0301462278800155 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Fairman-Williams ME, Guenther U-P, Jankowsky E. SF1 and SF2 helicases: family matters. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2010;20(3):313–324. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2010.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fucito S (2008) Caracterización funcional de la proteína NS3 del virus del dengue (Functional characterization of the dengue virus NS3 protein). Ph.D. thesis, Universidad de Buenos Aires. Facultad de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Buenos Aires, Argentina. Document available under request

- Gebhard LG, Kaufman SB, Gamarnik AV. Novel ATP-independent RNA annealing activity of the dengue virus NS3 helicase. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e36244. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebhard LG, Incicco JJ, Smal C, Gallo M, Gamarnik AV (2014) Monomeric nature of dengue virus NS3 helicase and thermodynamic analysis of the interaction with single-stranded RNA. Nucleic Acids Res 42(18):11668–11686. 10.1093/nar/gku812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gilbert SP, Webb MR, Brune M, Johnson KA. Pathway of processive ATP hydrolysis by kinesin. Nature. 1995;373(6516):671–676. doi: 10.1038/373671a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubler DJ. Epidemic dengue/dengue hemorrhagic fever as a public health, social and economic problem in the 21st century. Trends Microbiol. 2002;10(2):100–103. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(01)02288-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton NS, Perera R, Berger KL, Khadka S, LaCount DJ, Kuhn RJ, Randall G. Dengue virus nonstructural protein 3 redistributes fatty acid synthase to sites of viral replication and increases cellular fatty acid synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2010;107(40):17345–17350. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010811107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henn A, Bradley MJ, De La Cruz EM. ATP utilization and RNA conformational rearrangement by DEAD-box proteins. Annu Rev Biophys. 2012;41(1):247–267. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-050511-102243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henn A, Bradley MJ, De La Cruz EM. ATP utilization and RNA conformational rearrangement by DEAD-box proteins. Annu Rev Biophys. 2012;41(1):247–267. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-050511-102243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Incicco JJ, Gebhard LG, Gonzalez-Lebrero RM, Gamarnik AV, Kaufman SB (2013) Steady-state NTPase activity of dengue virus NS3: number of catalytic sites, nucleotide specificity and activation by ssRNA. PLoS One 8(3):e58508. 10.1371/journal.pone.0058508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Jankowsky E. RNA helicases at work: binding and rearranging. Trends Biochem Sci. 2011;36(1):19–29. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jankowsky E, Fairman ME. RNA helicases-one fold for many functions. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2007;17(3):316–324. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarmoskaite I, Russell R (2014) RNA helicase proteins as chaperones and remodelers. Ann Rev Biochem 83(1):697–725. 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060713-035546. (PMID: 24635478) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Jentes ES, Lash RR, Johansson MA, Sharp TM, Henry R, Brady OJ, Sotir MJ, Hay SI, Margolis HS, Brunette GW (2016) Evidence-based risk assessment and communication: a new global dengue-risk map for travellers and clinicians. Journal of travel medicine 23(6):taw062. 10.1093/jtm/taw062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kim JL, Morgenstern KA, Griffith JP, Dwyer MD, Thomson JA, Murcko MA, Lin C, Caron PR. Hepatitis C virus NS3 RNA helicase domain with a bound oligonucleotide: the crystal structure provides insights into the mode of unwinding. Structure. 1998;6(1):89–100. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(98)00010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin MK, Patel SS (2002) Helicase from hepatitis C virus, energetics of DNA binding*. J Biol Chem 277(33):29377–29385. ISSN 0021-9258. 10.1074/jbc.M112315200. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0021925818755920 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Li H, Clum S, You S, Ebner KE, Padmanabhan R. The serine protease and RNA-stimulated nucleoside triphosphatase and RNA helicase functional domains of dengue virus type 2 NS3 converge within a region of 20 amino acids. J Virol. 1999;73(4):3108–3116. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.3108-3116.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao J-C. Mechanical transduction mechanisms of RecA-like molecular motors. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2011;29(3):497–507. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2011.10507401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohman TM, Bjornson KP. Mechanisms of helicase-catalyzed DNA unwinding. Annual Reviews of Biochemistry. 1996;65:169–214. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.001125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohman TM, Bujalowski W (1991) [Thermodynamic methods for model-independent determination of equilibrium binding isotherms for protein-DNA interactions: spectroscopic approaches to monitor binding. In Protein - DNA Interactions, volume 208 of Methods in Enzymology, pp 258–290. Academic Press. 10.1016/0076-6879(91)08017-C. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/007668799108017C [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lohman TM, Tomko EJ, Wu CG. Non-hexameric DNA helicases and translocases: mechanisms and regulation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9(5):391–401. doi: 10.1038/nrm2394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- London WP. Steady state kinetics of an enzyme reaction with one substrate and one modifier. The bulletin of mathematical biophysics. 1968;30:253–277. doi: 10.1007/bf02476694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J, Jiang C, Li X, Jiang L, Li Z, Schneider-Poetsch T, Liu J, Yu K, Liu JO, Jiang H, Luo C, Dang Y (2015) A gating mechanism for Pi release governs the mRNA unwinding by eIF4AI during translation initiation. Nucleic Acids Res 43(21):10157–10167, 10. ISSN 0305-1048. 10.1093/nar/gkv1033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Luo D, Xu T, Hunke C, Gruber G, Vasudevan SG, Lescar J (2008) Crystal structure of the NS3 protease-helicase from dengue virus. J Virol 82(1):173–183. 10.1128/jvi.01788-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Luo D, Xu T, Watson RP, Scherer-Becker D, Sampath A, Jahnke W, Yeong SS, Wang CH, Lim SP, Strongin A, et al. Insights into RNA unwinding and ATP hydrolysis by the flavivirus NS3 protein. The EMBO journal. 2008;27(23):3209–3219. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh JA, Forman-Kay JD. Sequence determinants of compaction in intrinsically disordered proteins. Biophys J. 2010;98(10):2383–2390. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascotti DP, Lohman TM. Thermodynamics of single-stranded RNA binding to oligolysines containing tryptophan. Biochemistry. 1992;31(37):8932–8946. doi: 10.1021/bi00152a033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matson SW (1991) DNA helicases of Escherichia coli. Volume 40 of Progress in Nucleic Acid Research and Molecular Biology, pp 289–326. Academic Press. 10.1016/S0079-6603(08)60845-4. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0079660308608454 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Matson SW, Kaiser-Rogers KA. DNA helicases. Ann Rev. Biochem. 1990;59(1):289–329. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.59.070190.001445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matusan AE, Pryor MJ, Davidson AD, Wright PJ. Mutagenesis of the dengue virus type 2 NS3 protein within and outside helicase motifs: effects on enzyme activity and virus replication. J Virol. 2001;75(20):9633–9643. doi: 10.1128/jvi.75.20.9633-9643.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGhee JD, von Hippel PH (1974) Theoretical aspects of DNA-protein interactions: co-operative and non-co-operative binding of large ligands to a one-dimensional homogeneous lattice. J Mol Biol 86(2):469–489. ISSN 0022-2836. 10.1016/0022-2836(74)90031-X. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/002228367490031X [DOI] [PubMed]

- Pang PS, Jankowsky E, Planet PJ, Pyle AM. The hepatitis C viral NS3 protein is a processive DNA helicase with cofactor enhanced RNA unwinding. The EMBO Journal. 2002;21(5):1168–1176. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.5.1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perera R, Kuhn RJ. Structural proteomics of dengue virus. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2008;11(4):369–377. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter DJT (1998) A kinetic analysis of the oligonucleotide-modulated ATPase activity of the helicase domain of the NS3 protein from hepatitis C virus: the first cycle of interaction of ATP with the enzyme is unique. J Biol Chem 273(23):14247–14253. 10.1074/jbc.273.23.14247 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Pyle AM. Translocation and unwinding mechanisms of RNA and DNA helicases. Annu Rev Biophys. 2008;37(1):317–336. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Record MT, Anderson CF, Lohman TM. Thermodynamic analysis of ion effects on the binding and conformational equilibria of proteins and nucleic acids: the roles of ion association or release, screening, and ion effects on water activity. Q Rev Biophys. 1978;11(2):103–178. doi: 10.1017/s003358350000202x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampath A, Xu T, Chao A, Luo D, Lescar J, Vasudevan SG. Structure-based mutational analysis of the NS3 helicase from dengue virus. J Virol. 2006;80(13):6686–6690. doi: 10.1128/jvi.02215-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarto C, Kaufman SB, Estrin DA, Arrar M (2020) Nucleotide-dependent dynamics of the dengue NS3 helicase. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Proteins and Proteomics 1868(8):140441. 10.1016/j.bbapap.2020.140441 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Tanner NK, Cordin O, Banroques J, Doère M, Linder P. The Q motif: a newly identified motif in DEAD box helicases may regulate ATP binding and hydrolysis. Mol Cell. 2003;11(1):127–138. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waggoner JJ, Gresh L, Vargas MJ, Ballesteros G, Tellez Y, Soda KJ, Sahoo MK, Nuñez A, Balmaseda A, Harris E et al (2016) Viremia and clinical presentation in Nicaraguan patients infected with Zika virus, chikungunya virus, and dengue virus. Clin Infect Dis ciw589. 10.1093/cid/ciw589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wang C-C, Huang Z-S, Chiang P-L, Chen C-T, Wu H-N (2009) Analysis of the nucleoside triphosphatase, RNA triphosphatase, and unwinding activities of the helicase domain of dengue virus NS3 protein. FEBS Lett 583(4):691–696. 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.01.008https://febs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1016/j.febslet.2009.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wang Q, Arnold JJ, Uchida A, Raney KD, Cameron CE. Phosphate release contributes to the rate-limiting step for unwinding by an RNA helicase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(4):1312–1324. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong I, Moore KJM, Bjornson KP, Hsieh J, Lohman TM. ATPase activity of Escherichia coli Rep helicase is dramatically dependent on DNA ligation and protein oligomeric states. Biochemistry. 1996;35(18):5726–5734. doi: 10.1021/bi952959i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2023) Dengue and severe dengue. Accessed 31 July 2023. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dengue-and-severe-dengue

- Xu T, Sampath A, Chao A, Wen D, Nanao M, Chene P, Vasudevan SG, Lescar J (2005) Structure of the dengue virus helicase/nucleoside triphosphatase catalytic domain at a resolution of 2.4 A. J Virol 79(16):10278–10288. 10.1128/jvi.79.16.10278-10288.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ye J, Osborne AR, Groll M, Rapoport TA (2004) Reca-like motor ATPases–lessons from structures. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics 1659(1):1–18. ISSN 0005-2728. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2004.06.003. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0005272804001677 [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable

Not applicable