Abstract

Purpose

To investigate the treatment outcome of nocturnal enuresis (NE) according to first-morning urine osmolality (Uosm) before treatment.

Materials and Methods

Ninety-nine children (mean age, 7.2±2.1 y) with NE were enrolled in this retrospective study and divided into two groups according to first-morning Uosm results, that is, into a low Uosm group (<800 mOsm/L; 38 cases, 38.4%) or a high Uosm group (≥800 mOsm/L; 61 cases, 61.6%). Baseline parameters were obtained from frequency volume charts of at least 2 days, uroflowmetry, post-void residual volume, and a questionnaire for the presence of frequency, urgency, and urinary incontinence. Standard urotherapy and pharmacological treatment were administered initially in all cases. Enuresis frequency and response rates were analyzed at around 1 month and 3 months after treatment initiation.

Results

The level of first-morning Uosm was 997.1±119.6 mOsm/L in high Uosm group and 600.9±155.9 mOsm/L in low Uosm group (p<0.001), and first-morning voided volume (p=0.021) and total voided volume (p=0.019) were significantly greater in the low Uosm group. Furthermore, a significantly higher percentage of children in the low Uosm group had a response rate of ≥50% (CR or PR) at 1 month (50.0% vs. 24.6%; p=0.010) and 3 months (63.2% vs. 36.1%; p=0.009).

Conclusions

Treatment response rates are higher for children with NE with a lower first-morning Uosm.

Keywords: Child, Nocturnal enuresis, Osmolar concentration, Urinalysis, Urinary bladder

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Nocturnal enuresis (NE) is defined as intermittent incontinence of urine while sleeping in children over the age of 5 [1]. The prevalence of NE has been reported to be about 5.6% among children aged 5 to 13 years [2]. Although NE is not fatal or life-threatening, it does present a significant risk of psycho-social depression in patients and families, and thus immediate adequate treatment is required.

The pathophysiology of primary NE involves impaired arousal from deep sleep in response to a full bladder, coupled with nocturnal polyuria or reduced bladder functional capacity while sleeping [3]. Although multiple etiologic factors can contribute to NE, treatments target these three major factors [4].

According to the guidelines published by the International Children’s Continence Society (ICCS) in 2011, the standard treatment for non-monosymptomatic NE (NMSNE) is an enuresis alarm or desmopressin (1-desamino-8-D-arginine vasopressin, dDAVP), a vasopressin analogue. The dDAVP leads to urinary concentration and decreases urine volume like vasopressin (antidiuretic hormone) and is widely reported to decrease nocturnal urine volume and numbers of wet nights [5,6].

Urine osmolality (Uosm) provides a measure of the number of dissolved molecules in urine per unit of water and urine concentration. Uosm is more accurate than specific gravity, and can be used to diagnose a variety of urinary concentration-associated disorders [7]. Furthermore, several studies have investigated the relation between NE and first-morning osmolality, but results have been contradictory [8,9]. Nevéus et al. [10], in a study of 12 enuretic children, reported responders to therapy had significantly lower baseline Uosm values than non-responders. Dehoorne et al. [11], in a study of 42 children with monosymptomatic NE (MSNE) and night polyuria with a high Uosm (>850 mmol/L), reported no response to intranasal dDAVP, whereas Sözübir et al. [12], in a study of 67 children, reported a significantly higher proportion of those with an Uosm of <800 mOsm/L responded to dDAVP. However, these studies have been conducted studies limited to a small number of patients and especially MSNE among the types of NE. Therefore, it is thought that a study targeting a large number of patients with all kinds of NE is necessary.

This study aimed to evaluate whether urine concentration in NE is associated with treatment outcomes. In addition, we also assessed the effects of patient characteristics on treatment outcomes by classifying patients into MSNE and NMSNE groups.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Data acquisition

After obtaining approval from Institutional Review Board of Pusan National University Yangsan Hospital (IRB number: 05-2022-188), a retrospective chart review was performed on the prospective cohort data of all children that underwent treatment for NE at Pusan National University Children’s Hospital from September 2019 to June 2021. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents of all children when they visited our hospital.

Ninety-nine children with NE (>3 times per week) were included in the study. Patients diagnosed with organic causes, such as congenital urinary tract anomaly, congenital or acquired neurologic disorder, urinary tract infection, or spina bifida occulta, were excluded.

2. Patients evaluation

All patients completed a questionnaire and a 48-hour frequency/volume (48-h F/V) chart. The questionnaire included items on medical history and urinary symptoms, including frequency, urgency, urge incontinence, and dysuria. Questionnaire responses and 48-h F/V chart findings were used to confirm the presence of lower urinary tract symptom (LUTS). Leech scores were calculated using Kidney, Ureter, and Bladder X-ray findings for all patients.

3. First-morning urine collection

First-morning urine samples were collected from all patients on second hospital visits. Patients and parents were instructed to collect first-morning samples in plastic cups provided and to keep them refrigerated at 4℃. Samples were evaluated promptly on arrival at the hospital.

4. Patient analysis

The 99 patients were divided into two groups: (1) the low Uosm group with a first-morning Uosm of <800 mOsm/L or the (2) high Uosm group with a first-morning Uosm of ≥800 mOsm/L [13].

Daytime maximum voided volume (MVV), first-morning VVs, and total VVs were obtained from 48-h F/V charts. Uroflowmetry (UFM) and post-void residual volume (PVR) findings, maximum flow rates (Qmax), VVs, and PVRs were also subjected to analysis. Estimated bladder capacities (EBCs) were calculated using the formula [(age in years+1)×30] mL.

5. Treatment and response rate

Following pre-treatment evaluations of patient characteristics, 48-h F/V charts, UFM and PVR, standard urotherapy and pharmacological therapy were provided in accordance with ICCS recommendations. Standard urotherapy included an introduction to the treatment of LUTS and lifestyle modifications (balanced fluid intake, restriction of night fluid intake, timed bladder and bowel emptying, and optimal posture during voiding). Primary pharmacological therapy included desmopressin (dDAVP), propiverine, and/or imipramine. These drugs were used based on consideration of symptom severities and administrated in the same manner, regardless of presence of any other LUTS and a history of bladder dysfunction. Pharmacological treatment was started with desmopressin, and the dose was increased and decreased step by step. Propiverine and imipramine were added according to symptoms. Standard urotherapy was continued during pharmacological treatment.

The response rates were assessed at one and three months after treatment commencement. Based on the number of enuresis frequency before treatment, the degree of improvement in the number of enuresis frequency at 1 month and 3 months was defined as the response rate. Patients were categorized to three groups; complete response (CR), partial response (PR), or no response (NR) groups. CR was defined as no wet night. PR was defined as a reduction of ≥50%, and NR as a reduction of <50%. Differences between group daytime MVVs, VVs, total VVs, percentage reductions in wet nights, and response rates were analyzed.

In addition, subanalysis was conducted by dividing patients into a MSNE group without daytime LUTS (frequency, urgency, and/or urge incontinence) or a NMSNE group with daytime LUTS.

6. Statistical analysis

SPSS version 26 (IBM Corp.) was used for the statistical analyses. All p-value of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. The significances of differences between patient characteristics at first visit, 48-h F/V chart findings, UFM and PVR data, and treatment outcomes were determined using the student’s t-test and the Mann–Whitney U test, and the significances of intergroup differences were determined using the Pearson’s chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test.

RESULTS

1. All patients

Ninety-nine NE patients (53 boys and 46 girls) of mean age 7.2±2.1 years (5–14 y) constituted the study cohort and were allocated to the low or high Uosm groups (n= 38 and 61, respectively) (Table 1).

Table 1. Patient characteristics.

| Variable | All patients | Low osmolality group | High osmolality group | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients number | 99 (100.0) | 38 (38.4) | 61 (61.6) | ||

| Sex (boy/girl) | 53/46 | 21/17 | 32/29 | 0.786a | |

| Age (y) | 7.2±2.1 | 7.8±2.4 | 6.9±1.8 | 0.054b | |

| Height (cm) | 122.6±13.6 | 126.1±15.8 | 120.4±11.7 | 0.061b | |

| Weight (kg) | 28.1±10.9 | 29.9±11.9 | 27.0±10.3 | 0.209b | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 18.0±3.3 | 17.9±3.3 | 18.1±3.4 | 0.815b | |

| Gestational age (wk) | 38.7±1.9 | 38.6±2.4 | 38.8±1.5 | 0.534b | |

| Birth body weight (kg) | 3.2±0.5 | 3.2±0.6 | 3.2±0.5 | 0.881b | |

| Follow-up period (mo) | 7.8±5.1 | 7.8±5.9 | 7.8±4.6 | 0.987b | |

| First-morning urine osmolality (mOsm/L) | 845.1±235.5 | 600.9±155.9 | 997.1±119.6 | <0.001b | |

| Enuresis frequency (times/wk) | 4.7±2.0 | 4.4±2.0 | 4.9±2.1 | 0.273b | |

| Constipation on KUB | 38 (38.4) | 17 (44.7) | 21 (34.4) | 0.305a | |

| Frequency volume chart | |||||

| Daytime MVV (mL) | 162.4±94.9 | 184.3±119.4 | 148.2±72.8 | 0.099b | |

| First morning VV (mL) | 148.1±92.5 | 178.8±114.1 | 128.4±69.7 | 0.021b | |

| Total urine volume (mL) | 591.2±299.5 | 690.4±370.5 | 526.8±223.7 | 0.019b | |

| Uroflowmetry | |||||

| Qmax (mL/s) | 19.3±6.7 | 19.9±7.5 | 19.0±6.2 | 0.502b | |

| VV (mL) | 140.7±71.1 | 146.5±96.2 | 137.0±49.4 | 0.574b | |

| PVR (mL) | 13.5±11.5 | 15.2±13.1 | 12.5±10.2 | 0.255b | |

| EBC (mL) | 246.2±62.9 | 262.7±71.4 | 235.9±55.2 | 0.053b | |

| MVV/EBC (%) | 59.4±29.8 | 66.3±33.8 | 55.0±26.4 | 0.075b | |

| VV/EBC (%) | 58.0±23.4 | 55.0±27.5 | 59.9±20.3 | 0.313b | |

| MSNE patients | 41 (41.4) | 12 (31.6) | 29 (47.5) | 0.117a | |

| NMSNE patients | 58 (58.6) | 26 (68.4) | 32 (52.5) | ||

| Frequency | 35 (35.4) | 18 (47.4) | 17 (27.9) | 0.048a | |

| Urgency | 35 (35.4) | 13 (34.2) | 22 (36.1) | 0.851a | |

| Urge incontinence | 6 (6.1) | 3 (7.9) | 3 (4.9) | 0.546a | |

Values are presented as number (%) or mean±standard deviation.

BMI, body mass index; KUB, kidney, ureter and bladder X-ray; MVV, maximum voided volume; VV, voided volume; PVR, post-void residual volume; EBC, estimated bladder capacity; MSNE, monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis; NMSNE, non-monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis.

a:Chi-square test.

b:t-test.

p<0.05 was assumed as statistically significant.

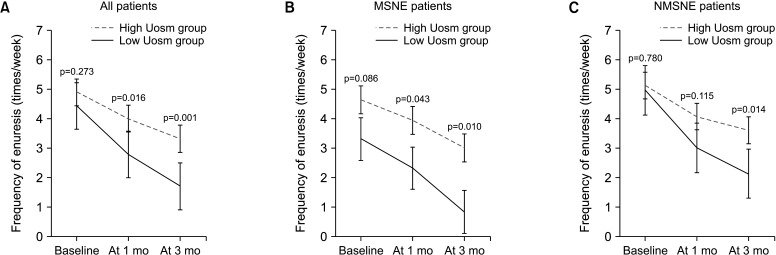

Enuresis frequencies before treatment were 4.4±2.0 and 4.9±2.1 per week in the low and high Uosm groups, respectively (p=0.273) (Fig. 1). The first-morning Uosm values at baseline were significantly different in the low and high Uosm groups (600.9±155.9 and 997.1±119.6 mOsm/L, respectively). Heights, weights, body mass index, gestational ages, birth body weights, and treatment periods were similar in the two groups (Table 1).

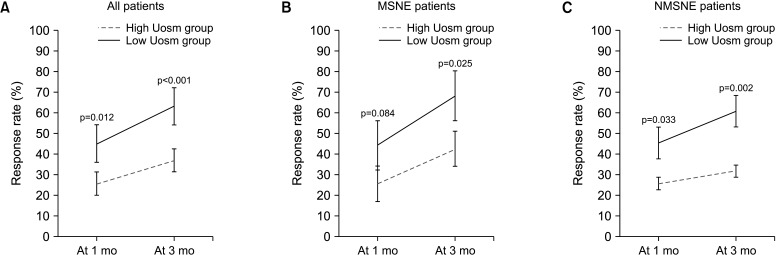

Fig. 1. Treatment outcomes according to the frequency of enuresis. (A) All study subjects and children with (B) MSNE or (C) NMSNE. MSNE, monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis; NMSNE, non-monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis.

Mean first-morning VV at baseline was significantly higher in the low Uosm group 178.8±114.1 mL vs. 128.4±69.7 mL (p=0.021), and mean total VV was significantly higher in the low Uosm group (690.4±370.5 mL vs. 526.8±223.7 mL, respectively, p=0.019) (Table 1).

At 1 month and 3 months after treatment commencement, the frequency of enuresis decreased significantly in both groups, but the low Uosm group showed a greater change (p=0.016, 0.001, respectively) (Fig. 1). In addition, response rates increased between 1 and 3 months in both groups but were more pronounced in the low Uosm group (p=0.012, <0.001, respectively). Furthermore, a significantly higher percentage of children in the low Uosm group had a response rate of ≥50% (CR or PR) at 1 month and 3 months (p=0.010, 0.009, respectively) (Table 2, Fig. 1). The multivariant analysis of the response rate and frequency of enuresis is presented in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

Table 2. Treatment outcomes.

| Variable | Patients number | Low osmolality group | High osmolality group | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients number | 99 (100.0) | 38 (38.4) | 61 (61.6) | |||

| Response at 1 months | ||||||

| CR or PR | 34 (34.3) | 19 (50.0) | 15 (24.6) | 0.010a | ||

| NR | 65 (65.7) | 19 (50.0) | 46 (75.4) | |||

| Response at 3 months | ||||||

| CR or PR | 46 (46.5) | 24 (63.2) | 22 (36.1) | 0.009a | ||

| NR | 53 (53.5) | 14 (36.8) | 39 (63.9) | |||

| MSNE patients number | 41 (100.0) | 12 (29.3) | 29 (70.7) | |||

| Response at 1 months | ||||||

| CR or PR | 12 (29.3) | 5 (41.7) | 7 (24.1) | 0.285b | ||

| NR | 29 (70.7) | 7 (58.3) | 22 (75.9) | |||

| Response at 3 months | ||||||

| CR or PR | 19 (46.3) | 7 (58.3) | 12 (41.4) | 0.322a | ||

| NR | 22 (53.7) | 5 (41.7) | 17 (58.6) | |||

| NMSNE patients number | 58 (100.0) | 26 (44.8) | 32 (55.2) | |||

| Response at 1 months | ||||||

| CR or PR | 22 (37.9) | 14 (53.8) | 8 (25.0) | 0.024a | ||

| NR | 36 (62.1) | 12 (46.2) | 24 (75.0) | |||

| Response at 3 months | ||||||

| CR or PR | 27 (46.6) | 17 (65.4) | 10 (31.3) | 0.010a | ||

| NR | 31 (53.4) | 9 (34.6) | 22 (68.8) | |||

Values are presented as number (%).

CR, complete response; PR, partial response; NR, no response; MSNE, monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis; NMSNE, non-monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis.

a:Chi-square test.

b:Fisher’s exact test.

p<0.05 was assumed as statistically significant.

2. MSNE patients

For MSNE patients, only first-morning Uosm differed significantly in the low and high Uosm subgroups (637.8±148.5 mOsm/L vs. 976.9±94.1 mOsm/L; p<0.001) (Table 3). The frequency of enuresis tended to decrease in both subgroups and was significantly different in these subgroups at 1 month (2.33±2.07 vs. 3.94±2.44; p=0.043) and 3 months (0.83±0.97 vs. 3.01±2.59; p=0.010) (Fig. 1). Although response rate tended to improve in both subgroups, statistical significance was only achieved after 3 months of treatment (68.3±33.5 vs. 42.6±39.4 in the low and high Uosm subgroups, respectively; p=0.025). Percentages of patients with a response rate of ≥50% or more (CR or PR) in the two subgroups were no different at 1 or 3 months (Table 2). The multivariant analysis of the response rate and frequency of enuresis is presented in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

Table 3. Patient characteristics in MSNE.

| Variable | MSNE patients | Low osmolality group | High osmolality group | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients number | 41 (100.0) | 12 (29.3) | 29 (70.7) | ||

| Sex (boy/girl) | 16/25 | 5/7 | 11/18 | 0.231a | |

| Age (y) | 7.7±2.1 | 8.4±2.5 | 7.5±19 | 0.202c | |

| Height (cm) | 127.0±13.7 | 132.5±15.3 | 124.9±12.6 | 0.116c | |

| Weight (kg) | 31.0±12.2 | 32.7±12.6 | 30.3±12.2 | 0.562d | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 18.5±3.7 | 17.6±3.2 | 18.8±3.8 | 0.378c | |

| Gestational age (wk) | 39.1±1.3 | 38.8±1.0 | 39.3±1.4 | 0.127d | |

| Birth body weight (kg) | 3.3±0.5 | 3.4±0.4 | 3.3±0.5 | 0.431c | |

| Follow-up period (mo) | 8.0±5.0 | 7.8±6.1 | 8.1±4.5 | 0.436d | |

| First-morning urine osmolality (mOsm/L) | 877.7±191.5 | 637.8±148.5 | 976.9±94.1 | <0.001c | |

| Constipation on KUB | 13 (31.7) | 4 (33.3) | 9 (31.0) | >0.999b | |

| Frequency volume chart | |||||

| Daytime MVV (mL) | 184.5±116.0 | 210.4±171.1 | 173.4±84.2 | 0.362c | |

| First morning VV (mL) | 162.3±92.3 | 176.8±120.0 | 155.9±79.2 | 0.538c | |

| Total urine volume (mL) | 562.0±246.1 | 565.0±335.8 | 560.7±206.8 | 0.465d | |

| Uroflowmetry | |||||

| Qmax (mL/s) | 20.5±5.7 | 21.2±6.9 | 20.2±5.2 | 0.599c | |

| VV (mL) | 159.7±88.2 | 194.7±137.1 | 144.7±53.0 | 0.244c | |

| PVR (mL) | 14.2±10.6 | 16.4±10.3 | 13.3±10.7 | 0.392c | |

| EBC (mL) | 261.9±63.7 | 281.9±75.2 | 253.6±57.7 | 0.200c | |

| MVV/EBC (%) | 63.3±29.1 | 62.8±30.5 | 63.4±29.0 | 0.954c | |

| VV/EBC (%) | 60.7±24.8 | 65.0±33.6 | 58.8±20.5 | 0.716d | |

Values are presented as number (%) or mean±standard deviation.

MSNE, monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis; BMI, body mass index; KUB, kidney, ureter and bladder X-ray; MVV, maximum voided volume; VV, voided volume; PVR, post-void residual volume; EBC, estimated bladder capacity.

a:Chi-square test.

b:Fisher’s exact test.

c:t-test.

d:Mann–Whitney test.

p<0.05 was assumed as statistically significant.

3. NMSNE patients

NMSNE patients in the low Uosm subgroup had a larger bladder capacity than those in the high Uosm subgroup at baseline. Daytime MVV, first-morning VV, total VV, MVV/EBC ratio, and VV/EBC ratio results at baseline were greater in the low Uosm subgroup (p<0.05) (Table 4).

Table 4. Patient characteristics in NMSNE.

| Variable | NMSNE patients | Low osmolality group | High osmolality group | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients number | 58 (100.0) | 26 (44.8) | 32 (55.2) | ||

| Sex (boy/girl) | 30/28 | 16/10 | 14/18 | 0.178a | |

| Age (y) | 6.8±2.0 | 7.5±2.3 | 6.3±1.6 | 0.090c | |

| Height (cm) | 119.5±12.8 | 123.4±15.4 | 116.3±9.2 | 0.046b | |

| Weight (kg) | 26.1±9.5 | 28.6±11.5 | 24.0±7.2 | 0.226c | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 17.7±3.1 | 18.0±3.4 | 17.4±2.8 | 0.542c | |

| Gestational age (wk) | 38.4±2.2 | 38.5±2.8 | 38.4±1.6 | 0.356c | |

| Birth body weight (kg) | 3.1±0.5 | 3.1±0.6 | 3.1±0.5 | 0.787b | |

| Follow-up period (mo) | 7.6±5.2 | 7.8±5.9 | 7.5±4.7 | 0.718c | |

| First-morning urine osmolality (mOsm/L) | 822.0±261.3 | 583.9±159.2 | 1,015.5±137.7 | <0.001c | |

| Constipation on KUB | 25 (43.1) | 13 (50.0) | 12 (37.5) | 0.339a | |

| Frequency volume chart | |||||

| Daytime MVV (mL) | 146.8±74.0 | 172.3±87.9 | 125.4±52.4 | 0.014c | |

| First morning VV (mL) | 139.0±92.3 | 179.6±113.9 | 106.3±52.4 | 0.007c | |

| Total urine volume (mL) | 611.0±331.6 | 743.5±377.7 | 496.2±237.1 | 0.002c | |

| Uroflowmetry | |||||

| Qmax (mL/s) | 18.6±7.2 | 19.3±7.8 | 17.9±6.8 | 0.516c | |

| VV (mL) | 127.4±53.0 | 124.3±61.5 | 130.0±45.6 | 0.349c | |

| PVR (mL) | 13.1±12.1 | 14.6±14.4 | 11.7±9.9 | 0.590c | |

| EBC (mL) | 235.1±60.5 | 253.8±69.2 | 219.9±48.3 | 0.090c | |

| MVV/EBC (%) | 59.9±30.3 | 67.8±35.6 | 48.2±22.2 | 0.014b | |

| VV/EBC (%) | 56.1±22.3 | 50.4±23.5 | 61.0±20.5 | 0.029c | |

Values are presented as number (%) or mean±standard deviation.

NMSNE, non-monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis; BMI, body mass index; KUB, kidney, ureter and bladder X-ray; MVV, maximum voided volume; VV, voided volume; PVR, post-void residual volume; EBC, estimated bladder capacity.

a:Chi-square test.

b:t-test.

c:Mann–Whitney test.

p<0.05 was assumed as statistically significant.

NE frequencies of NMSNE patients showed a significant decreasing trend at 3 months versus baseline (2.13±2.24 vs. 3.61±2.38, p=0.014) (Fig. 1), but significantly greater improvements were observed in the low Uosm subgroup at 1 month (45.4±39.3 vs. 25.7±30.8, p=0.033) and 3 months (60.9±33.3 vs. 31.7±32.5, p=0.002). Furthermore, the percentages of children with a response rate of ≥50% (CR or PR) were significantly higher in the low Uosm subgroup at 1 month and 3 months than in the high Uosm subgroup (53.8% vs. 25.0%; p=0.024 and 65.4% vs. 31.3%; p=0.010, respectively) (Table 2, Fig. 2). The multivariant analysis of the response rate and frequency of enuresis is presented in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

Fig. 2. Treatment outcomes according to response rates. (A) All study subjects and children with (B) MSNE or (C) NMSNE. MSNE, monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis; NMSNE, non-monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis.

DISCUSSION

Through this study, we aimed to determine whether first-morning Uosm could be used to predict outcomes in children with NE. Numerous factors must be considered when diagnosing NE, but it is difficult to obtain sufficient information from children. Therefore, diagnoses are often made based on guardian-reported disease history. Objective information acquired directly from a child is undoubtedly helpful but generally is limited to urine test results, an enuresis diary, a voiding diary, and UFM results. Furthermore, it is often difficult to differentiate MSNE and NMSNE in clinical practice due to insufficient information.

This is a meaningful study as it explored the ability of first-morning Uosm, a surrogate of nighttime urine concentration, to predict treatment response in children with NE. These measurements can be obtained simply, safely, and cost-effectively in patients with MSNE or NMSNE.

Published studies on the usefulness of first-morning Uosm in children with NE have produced disparate results. Several studies concluded that baseline Uosm is not a significant predictor of response to dDAVP therapy [12,14,15,16,17,18]. However, different methodological and therapeutic approaches were used. Others have reported that differences were caused by the inclusion of children regardless of bladder volume [9,14,15,16] or the administration of oral tablets or intranasal therapies with known poor pharmacokinetic and dynamic properties [12,14,15,16,17], the use of nonstandard outcome criteria [14], small sample sizes [14,15,18], and the inclusion of children and adults in the study cohort [17].

On the other hand, several studies found baseline Uosm significantly predicts response to dDAVP therapy. In a recent prospective cohort study, performed by Abdovic et al. [9] to determine nature of the association between response and Uosm in children with primary MSNE, an older age and a lower Uosm were found to significantly favor CR to dDAVP lyophilisate. ROC analysis showed an optimal Uosm cut-off of ≤814 mOsm/L best predicted complete success (sensitivity 65% and specificity 75%, AUC=68.2%), and the odds ratio for complete success using this cut-off value was 5.57 (95% CI 1.588–19.551, p=0.007). The authors concluded that high baseline first-morning Uosm (>814 mOsm/L) suggests an alternative to dDAVP lyophilisate in MSNE because of a higher risk of treatment failure [9].

Since the pathophysiology of NE involves nocturnal polyuria, the same findings are observed in NMSNE and MSNE. In this study, to focus on nocturnal polyuria, treatment response was analyzed using first-morning Uosm results of children with NMSNE or MSNE. We found that for children with NMSNE, the percentage with a response rate of ≥50% (CR or PR) at 1 month and 3 months was significantly greater for those with a low baseline Uosm. Furthermore, in MSNE, the frequency of enuresis significantly decreased at 1 month and 3 months after treatment commencement. Nonetheless, regardless of NE type, overall trends (reduction in enuresis frequency, increase in treatment response rate) were similar, which supports the importance of identifying the presence of nocturnal polyuria to predict treatment NE outcomes in NMSNE and MSNE.

First-morning urine volume calculations are not easy in some cases of children with NE, especially among those with nightly enuresis episodes. Invasive methods include the use of a large diaper or even urethral catheterization. On the other hand, checking first-morning Uosm is straightforward, noninvasive, and safe.

NE in children can be classified as MSNE or NMSNE. Based on ICCS guidelines, MSNE is defined as NE without any other LUTS, while NMSNE is defined as NE with any other symptom of LUTS or history of bladder dysfunction [19]. Of the three etiologic factors; impaired arousal from deep sleep in response to a full bladder, coupled with nocturnal polyuria or reduced bladder functional capacity, a small MVV, regardless of nighttime or daytime, is presumed to be more common in NMSNE than MSNE. Because many patients with LUTS have a small MVV, patients with NMSNE could also have a small MVV. However, published reports have shown a high proportion of NE patients have a small MVV for age with or without other LUTS, which means MVV cannot be used to predict treatment response [20,21].

In our study, patients in the low Uosm group have more first-morning VV and total VV regardless of type of NE. It might mean that although they have adequate bladder functional capacity while sleeping but their ability to concentrate urine is low, resulting in nocturnal polyuria and NE. Therefore, their NE responds well to treatment, especially dDAVP. On the other hand, nocturnal polyuria might not be the cause of NE in patients in the high Uosm group. Therefore, their response to treatment in this study, mainly for nocturnal polyuria, was not so good.

In subgroup analysis, the main cause of NE in the low Uosm group in MSNE is probably the insufficient ability to concentrate urine, rather than drinking too much water or reduced bladder functional capacity while sleeping, impaired arousal from a deep sleep in response to a full bladder. In the same way, the main causes of NE in the high Uosm group in MSNE are reduced bladder functional capacity while sleeping and impaired arousal from a deep sleep in response to a full bladder, rather than drinking too much water and insufficient ability to concentrate urine. The cause of daytime LUTS in the low Uosm group in NMSNE is inability to recognize the appropriate time to void, and nocturnal polyuria is the cause of NE. On the other hand, reduced bladder functional capacity is the main cause of daytime LUTS and NE in the high Uosm group in NMSNE.

In addition, ICCS stated “treat the underlying LUTD symptoms first, as effective treatment of an overactive bladder (or postponement, dysfunctional voiding) can lead to cessation of nocturnal enuresis” in 2013 [22]. However, they added “there is no evidence-supported reason to delay specific anti enuretic therapy in the child whose daytime symptoms are minor and not a cause of concern for the family that is, some urgency, marginal incontinence episodes and/or high/low voiding frequency” in 2020 [23]. This change revealed that NE may improve even if pharmacotherapy with dDAVP as the main for NE is started at the same time as treatment for daytime LUTS but patients with small VV can be expected to have a poor therapeutic effect. In our study, it is thought that lower first-morning VV and high first-morning Uosm, which were seen in the high Uosm group, may have reduced the treatment effect of NE. However, the fact that both the MSNE and NMSNE groups showed the same findings suggests that first-morning Uosm is more strongly associated with treatment outcome than bladder function with daytime LUTS.

Several limitations of the current study require consideration. First, since urine was collected by first natural urination in the morning and not using a Foley catheter during the night, our results may differ from those of other studies. Second, the sample size was relatively small, which might have impacted the validity of the analysis performed on MSNE patients. Third, Uosm was checked only once. It has been recognized that Uosm requires repetition to improve its accuracy, reliability, and correct interpretation. Finally, we did not confirm that Uosm increases after treatment. Thus, we recommend a prospective, randomized control study or large-scale cohort study be conducted to confirm our results.

CONCLUSIONS

First-morning Uosm testing can be performed easily, safely, and cost-effectively even on children with NE. This study showed that NE children with lower first morning Uosm responded better to urotherapy and pharmacological therapy. Additionally, NE children with lower first morning Uosm in both MSNE and NMSNE responded better to treatment. However, additional large-scale studies are needed to determine the role of first-morning Uosm in NE.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by a 2023 research grant from Pusan National University Yangsan Hospital and was not supported financially or in kind by any external agency.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST: The authors have nothing to disclose.

FUNDING: None.

- Research conception and design: Jae Min Chung.

- Data acquisition: Jae Min Chung.

- Statistical analysis: Gwon Kyeong Lee.

- Data analysis and interpretation: Gwon Kyeong Lee.

- Drafting of the manuscript: Gwon Kyeong Lee.

- Critical revision of the manuscript: Jae Min Chung.

- Obtaining funding: Jae Min Chung.

- Supervision: Sang Don Lee.

- Approval of the final manuscript: Jae Min Chung.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary materials can be found via https://doi.org/10.4111/icu.20220377.

Multivariant analysis of response rate

Multivariant analysis of frequency of enuresis

References

- 1.Robson WL. Clinical practice. Evaluation and management of enuresis. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1429–1436. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0808009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chung JM, Lee SD, Kang DI, Kwon DD, Kim KS, Kim SY, et al. Korean Enuresis Association. An epidemiologic study of voiding and bowel habits in Korean children: a nationwide multicenter study. Urology. 2010;76:215–219. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walle JV, Rittig S, Bauer S, Eggert P, Marschall-Kehrel D, Tekgul S American Academy of Pediatrics; European Society for Paediatric Urology; European Society for Paediatric Nephrology; International Children’s Continence Society. Practical consensus guidelines for the management of enuresis. Eur J Pediatr. 2012;171:971–983. doi: 10.1007/s00431-012-1687-7. Erratum in: Eur J Pediatr 2013;172:285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim JM. Diagnostic value of functional bladder capacity, urine osmolality, and daytime storage symptoms for severity of nocturnal enuresis. Korean J Urol. 2012;53:114–119. doi: 10.4111/kju.2012.53.2.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tullus K, Bergström R, Fosdal I, Winnergård I, Hjälmås K. Efficacy and safety during long-term treatment of primary monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis with desmopressin. Swedish Enuresis Trial Group. Acta Paediatr. 1999;88:1274–1278. doi: 10.1080/080352599750030428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vande Walle JG, Bogaert GA, Mattsson S, Schurmans T, Hoebeke P, Deboe V, et al. Desmopressin Oral Lyophilisate PD/PK Study Group. A new fast-melting oral formulation of desmopressin: a pharmacodynamic study in children with primary nocturnal enuresis. BJU Int. 2006;97:603–609. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.05999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pagana KD, Pagana TJ. Mosby's manual of diagnostic and laboratory tests. 7th ed. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akagawa S, Tsuji S, Akagawa Y, Yamanouchi S, Kimata T, Kaneko K. Desmopressin response in nocturnal enuresis showing concentrated urine. Pediatr Int. 2020;62:701–704. doi: 10.1111/ped.14201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abdovic S, Cuk M, Hizar I, Milosevic M, Jerkovic A, Saraga M. Pretreatment morning urine osmolality and oral desmopressin lyophilisate treatment outcome in patients with primary monosymptomatic enuresis. Int Urol Nephrol. 2021;53:1529–1534. doi: 10.1007/s11255-021-02843-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nevéus T, Läckgren G, Tuvemo T, Stenberg A. Osmoregulation and desmopressin pharmacokinetics in enuretic children. Pediatrics. 1999;103:65–70. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dehoorne JL, Raes AM, van Laecke E, Hoebeke P, Vande Walle JG. Desmopressin resistant nocturnal polyuria secondary to increased nocturnal osmotic excretion. J Urol. 2006;176:749–753. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(06)00297-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sözübir S, Ergun G, Celik A, Ulman I, Avanoglu A. The influence of urine osmolality and other easily detected parameters on the response to desmopressin in the management of monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis in children. Minerva Urol Nefrol. 2006;58:207–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rushton HG, Belman AB, Zaontz M, Skoog SJ, Sihelnik S. Response to desmopressin as a function of urine osmolality in the treatment of monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis: a double-blind prospective study. J Urol. 1995;154:749–753. doi: 10.1097/00005392-199508000-00112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Unüvar T, Sönmez F. The role of urine osmolality and ions in the pathogenesis of primary enuresis nocturna and in the prediction of responses to desmopressin and conditioning therapies. Int Urol Nephrol. 2005;37:751–757. doi: 10.1007/s11255-005-1660-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Medel R, Dieguez S, Brindo M, Ayuso S, Canepa C, Ruarte A, et al. Monosymptomatic primary enuresis: differences between patients responding or not responding to oral desmopressin. Br J Urol. 1998;81 Suppl 3:46–49. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1998.00007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eller DA, Homsy YL, Austin PF, Tanguay S, Cantor A. Spot urine osmolality, age and bladder capacity as predictors of response to desmopressin in nocturnal enuresis. Scand J Urol Nephrol Suppl. 1997;183:41–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Folwell AJ, Macdiarmid SA, Crowder HJ, Lord AD, Arnold EP. Desmopressin for nocturnal enuresis: urinary osmolality and response. Br J Urol. 1997;80:480–484. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1997.00360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hara T, Ohtomo Y, Endo A, Niijima S, Yasui M, Shimizu T. Evaluation of urinary aquaporin 2 and plasma copeptin as biomarkers of effectiveness of desmopressin acetate for the treatment of monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis. J Urol. 2017;198:921–927. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2017.04.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Austin PF, Bauer SB, Bower W, Chase J, Franco I, Hoebeke P, et al. The standardization of terminology of lower urinary tract function in children and adolescents: update report from the standardization committee of the International Children's Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn. 2016;35:471–481. doi: 10.1002/nau.22751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shim M, Bang WJ, Oh CY, Kang MJ, Cho JS. Effect of desmopressin lyophilisate (MELT) plus anticholinergics combination on functional bladder capacity and therapeutic outcome as the first-line treatment for primary monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis: a randomized clinical trial. Investig Clin Urol. 2021;62:331–339. doi: 10.4111/icu.20200303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kang BJ, Chung JM, Lee SD. Evaluation of functional bladder capacity in children with nocturnal enuresis according to type and treatment outcome. Res Rep Urol. 2020;12:383–389. doi: 10.2147/RRU.S267417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Franco I, von Gontard A, De Gennaro M International Children's Continence Society. Evaluation and treatment of nonmonosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis: a standardization document from the International Children's Continence Society. J Pediatr Urol. 2013;9:234–243. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2012.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nevéus T, Fonseca E, Franco I, Kawauchi A, Kovacevic L, Nieuwhof-Leppink A, et al. Management and treatment of nocturnal enuresis-an updated standardization document from the International Children's Continence Society. J Pediatr Urol. 2020;16:10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2019.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Multivariant analysis of response rate

Multivariant analysis of frequency of enuresis