Abstract

Background

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most common cause of chronic liver disease worldwide. However, there is no clear consensus on optimal screening strategies and risk stratification. We conducted a systematic review of society guidelines to identify differences in recommendations regarding the screening, diagnosis, and assessment of NAFLD.

Methods

We searched PubMed, Web of Science, and Embase databases from January 1, 2015, to August 2, 2022. Two researchers independently extracted information from the guidelines about screening strategies, risk stratification, use of noninvasive tests (NITs) to assess hepatic fibrosis, and indications for liver biopsy.

Results

Twenty clinical practice guidelines and consensus statements were identified in our search. No guidelines recommended routine screening for NAFLD, while 14 guidelines recommended case finding in high-risk groups. Of the simple risk stratification models to assess for fibrosis, the fibrosis-4 score was the most frequently recommended, followed by the NAFLD fibrosis score. However, guidelines differed on which cutoffs to use and the interpretation of “high-risk” results.

Conclusion

Multiple guidelines exist with varying recommendations on the benefits of screening and interpretation of NIT results. Despite their differences, all guidelines recognize the utility of NITs and recommend their incorporation into the clinical assessment of NAFLD.

Keywords: NAFLD, FIB-4, NFS, elastography, guidelines

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most common cause of chronic liver disease worldwide, accounting for approximately 59% of cases.1 NAFLD represents a spectrum of disease characterized by excessive fat accumulation in the liver without another clear cause of injury such as alcohol. It is further subdivided into nonalcoholic fatty liver (NAFL) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). NAFL is defined as steatosis of greater than 5% of hepatocytes without inflammation, and NASH is defined as steatosis with evidence of inflammation and hepatocyte injury on histology.2 Although most patients with NAFLD do not progress to NASH, those who do are at significantly increased risk for the development of cirrhosis and other hepatic complications such as hepatocellular carcinoma. Approximately 7–30% of patients with NASH progress to cirrhosis,3 of whom approximately one-third develop end-stage liver complications.4 Over the past decade, NASH has emerged as the most rapidly growing cause of end-stage liver disease, threatening to overtake alcohol as the most common cause of liver transplantation in the United States.5 The true prevalence of NASH may be even higher as NASH requires liver biopsy for definitive diagnosis. A recent modeling study predicted that due to rising rates in obesity and diabetes in the United States, the prevalence of NAFLD-related liver disease and mortality will continue to increase through 2030.6 As such, public interest and concern regarding NAFLD has grown tremendously as the case burden increases and our understanding of this phenomenon deepens.

Although the precise mechanism behind NAFLD pathogenesis is not known, insulin resistance (IR) is widely believed to play a prominent role. As insulin sensitivity decreases, as does its ability to suppress hormone-sensitive lipase, leading to increased free fatty acid release from peripheral adipose tissue. Excess free fatty acid is eventually taken up by the liver, contributing to steatosis. IR-induced hyperinsulinemia also promotes hepatic synthesis of triglycerides, further contributing to steatosis.7 As such, conditions associated with IR, namely obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and the metabolic syndrome, have been shown to have strong bidirectional associations with the development of NAFLD.

Histologic staging and grading via liver biopsy is universally regarded as the gold standard for differentiating between NAFL and NASH, as well as for the quantification of hepatic fibrosis. However, liver biopsy is an expensive and invasive procedure with inherent risks for complications. Furthermore, the diagnostic yield may be prone to sampling error and the procedure itself may not be readily accessible to patients due to high cost and limited provider availability, particularly in underresourced patient populations. Given these limitations, along with the rising incidence of NAFLD, performing liver biopsies for all patients with NAFLD is not feasible. As such, much attention has been placed on NITs to assess the extent of fibrosis and to risk stratify patients who could benefit from liver biopsy. It is important to note that these NITs are used to assess for advanced fibrosis, not steatohepatitis, and cannot distinguish between NAFL and NASH. These tests can be subdivided into simple serum indices that are calculated from routine laboratory values (i.e., NAFLD fibrosis-4 score [FIB-4], AST to platelet ratio index [APRI]), specialized blood tests that detect unique biomarkers associated with hepatic fibrosis (i.e., enhanced liver fibrosis [ELF] test), and radiographic examinations that measure liver stiffness (i.e., vibration-controlled transient elastography [VCTE], shear wave elastography [SWE], magnetic resonance [MR] elastography). With proper use, these tests can rule out advanced disease and identify patients who are at high risk for fibrosis. These tests also have the potential to lower the number of specialist referrals and avoid unnecessary liver biopsies. However, society guidelines vary in their recommendations and cutoff values for these tests.

Despite the universal concern over this growing phenomenon, there is no clear consensus on optimal screening strategies and risk stratification in patients with NAFLD. Multiple professional societies have put forth clinical practice guidelines and consensus statements; however, upon close review, multiple differences exist in their recommendations (INASL,8 AACE,9 Egyptian guidelines,10 AGA,11 KASL,12 APASL,13 ALEH,14 Catalan guidelines,15 BASL,16 CSG,17 EASL,18 BSG,19 JSG,20 DGVS,21 AAEH22).These differences range from who to screen for NAFLD to which thresholds to employ when utilizing noninvasive tests (NITs). Prior review articles have compared society guidelines for NAFLD23, 24, 25; however, these articles focused on a small number of guidelines or compared guidelines that have since been changed or updated. With the emergence of newer studies, it is important to periodically reexamine current guidelines. We conducted a systematic review of clinical practice guidelines and professional society recommendations to identify areas of agreement and discordance in the screening, diagnosis, and assessment of NAFLD. We included the greatest number of guidelines representing a diverse group of countries and specifically focused on the use of noninvasive assessments of NAFLD risk.

Methods

A systematic review was performed following the guidelines in the “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses” (PRISMA) statement. The inclusion criteria were1 guidelines regarding the diagnosis and assessment of NAFLD in the general adult population,2 peer-reviewed full-text articles written in English3 published between January 1, 2015, and August 2, 2022,4 published by governmental agencies or scientific professional societies. Exclusion criteria were1 guidelines that focused on specific patient populations such as pediatrics, lean individuals, and diabetes2; outdated guidelines in which a newer version has since been published.

Literature Search Strategy

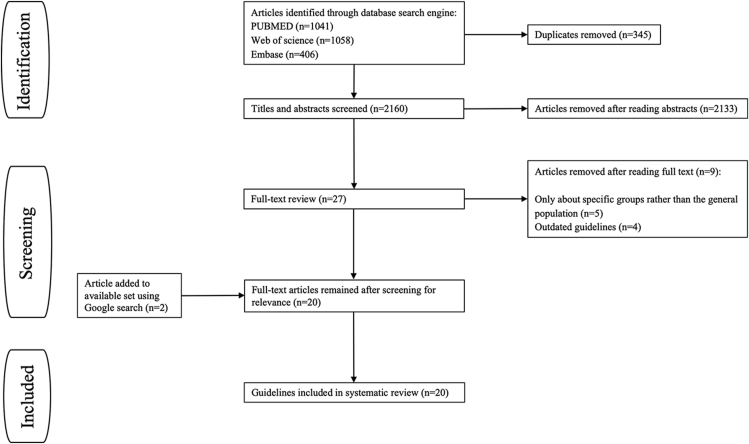

We conducted a search of the literature using PubMed (using appropriate MeSH terms), EMBASE (using preferred Emtree terms), and Web of Science. Our screening process and search method is detailed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart describing the study screening and selection process.

We used the following PubMed search protocol: (("Guidelines as Topic"[MeSH Terms] OR "Guideline"[Publication Type] OR "guideline∗"[All Fields] OR "recommendation∗"[All Fields] OR "protocol∗"[All Fields]) AND ("non alcoholic fatty liver disease"[MeSH Terms] OR ("non-alcoholic"[All Fields] AND "fatty"[All Fields] AND "liver"[All Fields]) OR "non alcoholic fatty liver disease"[All Fields] OR "non alcoholic fatty liver disease"[All Fields] OR ("non"[All Fields] AND "alcoholic"[All Fields] AND "fatty"[All Fields] AND "liver"[All Fields] AND "disease"[All Fields]))) AND (2015:2022[pdat]).

We used the following EMBASE search string: “practice guideline” AND (“nafld” OR “nonalcoholic fatty liver”/exp OR “nonalcoholic fatty liver”) AND [2015–2022]/py AND ([adolescent]/lim OR [adult]/lim OR [young adult]/lim OR [middle aged]/lim OR [aged]/lim OR [very elderly]/lim). We used the following Web of Science search string: guideline or protocol AND nafld or non alcoholic fatty liver disease.

Data Extraction

Two reviewers (PF and AS) independently reviewed all records and identified 20 relevant articles. PF and AS analyzed and extracted information from the 20 articles about screening recommendations, NITs, risk stratification, fibrosis assessment, and work-up strategies and algorithms.

Results

Who to Screen for Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD)?

In our systematic review, no guidelines recommend routine screening for NAFLD in the general population, citing inadequate cost–benefit ratios and uncertainty of treatment options and benefits of screening. We define “routine screening” as population-based detection of disease, and “case-finding” as targeted screening for disease in high-risk groups. Fourteen guidelines9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22 recommend case-finding for NAFLD in patients with high-risk features. Of those 14 guidelines, diabetes was cited as a high-risk feature in each guideline, and metabolic syndrome and obesity were cited in 13. The KASL does not cite obesity as a high-risk feature, and the Catalan guidelines do not cite metabolic syndrome as a high-risk feature. The KASL “recommends” case-finding for all patients with persistently elevated liver enzymes and/or patients with diabetes and to “consider” case-finding patients with metabolic syndrome.12 The BSG recommends case-finding for NAFLD in patients with type 2 diabetes, obesity, or metabolic syndrome but notes that the evidence on case-finding strategies in high-risk groups is limited and acknowledges that European and North American guidelines differ in this regard.19 Similarly, the AAEH recommends case-finding in high-risk groups (diabetes, metabolic syndrome, obesity) but acknowledges that data are inconclusive whether this strategy is sustainable and cost-effective. The EASL recommends case-finding for NAFLD in patients with obesity or metabolic syndrome and stated that case-finding for advanced disease is advisable in high-risk patients (age >50, metabolic syndrome, diabetes).18 Seven guidelines recommend case-finding in patients with abnormal liver enzymes,9,11,12,14,17,19,21 one guideline recommends case-finding in patients with a history of ischemic cardiovascular disease,16 and one guideline recommended case-finding in patients with a history of arterial hypertension.11, 12, 14, 17, 19, 21, 9 Two guidelines2,26 recommended against case-finding for NAFLD, even in high-risk groups. The AASLD cites uncertainties in diagnostic tests, treatment options, long-term benefits, and cost-effectiveness as reasons to defer case-finding, while the SBH simply states that there was no policy definition for tracking patients at high risk of developing NAFLD.2,26 Four guidelines8,27, 28, 29 do not mention case-finding strategies (Table 1). For patients with a diagnosis of NAFLD, 16 guidelines2,8,9,13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22,26,27,29 recommend screening for high-risk metabolic comorbidities such as diabetes, metabolic syndrome, dyslipidemia, and cardiovascular disease, noting the strong bidirectional relationship between these metabolic risk factors and NAFLD. Three guidelines (ALEH, CAMFIC, and AFEF) recommend the use of cardiovascular risk scoring systems such as the HeartSCORE for further risk stratification in patients with NAFLD. The BASL guidelines recommend more extensive testing for patients with severe NAFLD, defined as biopsy-proven NASH or ≥F2 fibrosis. For such patients, noninvasive assessment for subclinical atherosclerotic disease (i.e., coronary artery calcium score) is recommended. The INASL guidelines recommend screening for polycystic ovary syndrome in women with NAFLD and the metabolic syndrome.

Table 1.

Summary of Recommendations on Optimal Screening Strategies to Detect NAFLD.

| Screening strategies | Guidelines |

|---|---|

| Routine screening | None |

| Screen high risk patients | AACE, Egyptian guidelines, AGA, KASL, APASL, ALEH, Catalan guidelines, BASL, CSG, EASL, BSG, JSG, DGVS, AAEH. (14) |

| Diabetes | AACE, Egyptian guidelines, AGA, KASL, APASL, ALEH, Catalan guidelines, BASL, CSG, EASL, BSG, JSG, DGVS, AAEH. (14) |

| Obesity | AACE, Egyptian guidelines, AGA, APASL, ALEH, Catalan guidelines, BASL, CSG, EASL, BSG, JSG, DGVS, AAEH. (13) |

| Metabolic syndrome | AACE, Egyptian guidelines, AGA, KASL, APASL, ALEH, BASL, CSG, EASL, BSG, JSG, DGVS, AAEH. (13) |

| Elevated transaminases | AACE, AGA, KASL, ALEH, CSG, BSG, DGVS. (7) |

| History of ischemic cardiovascular disease | BASL. (1) |

| History of arterial hypertension | DGVS. (1) |

| Recommend against screening, even in high-risk patients | AASLD, SBH. (2) |

| Did not mention | AISF, NICE-UK, AFEF, INASL. (4) |

Abbreviations: AACE, American Association of Clinical Endocrinology; AAEH, Asociación Española para el Estudio del Hígado; AASLD, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; AFEF, French Association for the Study of the Liver; AGA, American Gastroenterology Association; AISF, Italian Association for the Study of the Liver; APASL, The Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver; ALEH, Latin American Association for the study of the liver; BASL, Belgian Association for the Study of the Liver; BSG, British Society of Gastroenterology; CSG, Chinese Society of Gastroenterology; DGVS, German Society of Gastroenterology, Digestive and Metabolic Diseases; EASL, European Association for the Study of the Liver; JSG, Japanese Society of Gastroenterology; INASL, India National Association for the Study of the Liver; KASL, The Korean Association for the Study of the Liver; NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; SBH, Brazilian Society of Hepatology.

Abdominal Ultrasound

Abdominal ultrasound (US) is the most frequently used method for the screening and diagnosis of NAFLD.30 Its advantages include widespread availability, relatively low cost, and overall safety of use. However, its clinical utility is limited due to its variable accuracy and inability to distinguish between NAFL and NASH. Negative findings on US cannot rule out NAFLD, as US requires the presence of steatosis in 12.5–33% of hepatocytes for optimal accuracy.31,32 Thus, US may miss patients with mild steatosis. Its performance is also less accurate in obese patients.31, 32

Despite these limitations, 10 guidelines10,12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18,21,22 recommend the use of US as the first-line test for the diagnosis of NAFLD. The AACE and AASLD do not recommend conventional US for the diagnosis of NAFLD.2,9 The AACE recommends use of transient elastography over US when available, citing its ability to quantify steatosis and assess fibrosis severity in one session.2, 9 For patients with high pretest probability for NAFLD, the AACE recommends bypassing US and proceeding with fibrosis assessment via the FIB-4 since the probability of having steatosis is high. The AASLD recommends the use of clinical decision aids such as NFS, FIB-4, and VCTE over conventional US, stating that its utility as a screening tool is unproven.3 Four guidelines8,11,15,26 state that US can be helpful but is not required and should be used in conjunction with other NITs. The AFEF stated that steatosis is most often discovered incidentally through imaging such as US but noted that to diagnose NAFLD, these findings must be observed in a metabolic context after other causes of steatosis are ruled out.29

Most guidelines agree that US can be useful in detecting moderate to high levels of steatosis and that positive results are highly suggestive of NAFLD. However, US should not be used alone and negative results cannot exclude the presence of NAFLD. Regardless of the results, US should be used in conjunction with other NITs. Once NAFLD is diagnosed, most commonly through US, assessment for hepatic fibrosis should be made using simple blood tests such as the NFS or FIB-4.

Fibrosis-4 (FIB-4)

The FIB-4 is a simple index developed by Sterling et al. in 2006 to predict liver fibrosis in patients with human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C coinfection.33 The algorithm uses age, AST, INR, and platelet count to generate a numerical score. Scores of <1.45 exclude advanced fibrosis with a negative predictive value of 90% and a sensitivity of 70%, while scores of >3.25 rule in advanced fibrosis with a positive predictive value of 65% and a specificity of 97%. The FIB-4 has since been validated for use in patients with NAFLD, with Shah et al. proposing cutoffs of scores of <1.3 to rule out fibrosis with a negative predictive value of 90%, and scores of >2.67 to rule in fibrosis with a positive predictive value of 80% NAFLD.34, 35, 36, 37

Eighteen guidelines2,9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22,26,27,29 recommend the use of FIB-4 for the assessment of NAFLD although guidelines differed on which cutoff values to use. Six guidelines9, 10, 11, 12,16,29 recommend the cutoffs proposed by Shah et al. of <1.3 as the lower cutoff to rule out fibrosis and >2.67 as the upper cutoff to rule in fibrosis. The AISF recommends a lower cutoff of <1.3 to rule out fibrosis but does not recommend a higher cutoff to rule in fibrosis. The Catalan guidelines also do not recommend a higher cutoff but instead recommends a lower cutoff of <1.3 in patients aged <65 and a lower cutoff of <2 in patients aged 65 or greater.15,27 The ALEH and DGVS recommend a lower cutoff of <1.3 for those under the age of 65, and a lower cutoff of <2.0 for patients greater than 65 years old, citing decreased specificity in patients aged 65 or greater, and an upper cutoff of >2.67.14,21 Of note, both the FIB-4 and NFS have been shown to have poor diagnostic accuracy when used to assess individuals younger than 35 years of age, with area under the receiving operating characteristic curves of 0.52 and 0.6, respectively. In patients aged 65 or greater, the specificity of the FIB-4 and NFS for detecting advanced fibrosis declined to 35% and 25%, respectively.38 The AASLD recommends the cutoff originally proposed by Sterling et al. of <1.45 as the lower cutoff and >3.25 as the upper cutoff.14, 21 The JSG recommends a lower cutoff of <1.3 and an upper cutoff of >3.25.20 Seven guidelines13,17, 18, 19,22,26,29 recommend the FIB-4 but did not specify cutoffs, and two guidelines8,28 did not mention the FIB-4 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of Recommendations on the Use of Abdominal Ultrasound, FIB-4, NFS, and APRI for the Diagnosis of NAFLD and Assessment of Hepatic Fibrosis Severity.

| Recommendations | Guidelines |

|---|---|

| Ultrasound | |

| Ultrasound is first line for detection of hepatic steatosis | Egyptian guidelines, AISF, KASL, APASL, ALEH, BASL, CSG, EASL, DGVS, AAEH. (10) |

| Ultrasound should be used in conjunction with other tests, but is optional and not necessarily first line | AGA, Catalan guidelines, SBH, INASL. (4) |

| Steatosis is most often discovered incidentally through imaging such as ultrasound, but findings must be in a metabolic context after other causes of steatosis are ruled out | AFEF. (1) |

| Ultrasound is not recommended; TE should be performed instead | AACE. (1) |

| Ultrasound is unproven as a screening tool | AASLD. (1) |

| No comment/does not specify | NICE-UK, JSG, BSG. (3) |

| FIB-4 | |

| Cutoff of <1.3 and >2.67 | AACE, Egyptian guidelines, AGA, KASL, BASL, AFEF. (6) |

| Cutoff of <1.3 and >3.25 | JSG. (1) |

| Cutoff of <1.56 and >3.25 | AASLD. (1) |

| Cutoff of <1.3 | AISF. (1) |

| Cutoff of <1.3 for age <65 | Catalan guidelines. (1) |

| Cutoff of <2 for age ≥65 | |

| Cutoff of <1.3 and >2.67 for age <65 | ALEH, DGVS. (2) |

| Cutoff of >2 and >2.67 for age ≥65 | |

| FIB-4 is recommended, but did not specify cutoffs | APASL, CSG, SBH, EASL, AFEF, BSG. (7) |

| FIB-4 was not mentioned | NICE-UK, INASL. (2) |

| NFS | |

| Cutoffs of <−1.45 and >0.67 | Egyptian guidelines, KASL, APASL, ALEH, BASL, AASLD, JSG, AFEF. (8) |

| Cutoff of <−1.45 and >0.67 for age <65 | DGVS. (1) |

| Cutoff of <0.12 and >0.67 for age ≥65 | |

| Cutoff of <−1.4 for age <65 | Catalan guidelines. (1) |

| Cutoff of <0.12 for age ≥65 | |

| Cutoff of <−1.45 | AISF. (1) |

| NFS is recommended, but did not specify cutoffs | CSG, SBH, EASL, AAEH, BSG, INASL. (6) |

| NFS is not recommended | AACE, AGA. (2) |

| NFS was not mentioned | NICE-UK. (1) |

| APRI | |

| Cutoff of <0.5 and >1.5 | Egyptian guidelines, APASL. (2) |

| Cutoff of <0.48 and >1.34 | AGA. (1) |

| APRI is recommended but did not specify cutoffs | SBH, EASL, INASL (3) |

| APRI is not recommended | ALEH, BASL, AASLD, CSG, DGVS. (5) |

| APRI was not mentioned | AACE, AISF, KASL, Catalan guidelines, BSG, JSG, NICE-UK, AFEF, AAEH. (9) |

Abbreviations: AACE, American Association of Clinical Endocrinology; AAEH, Asociación Española para el Estudio del Hígado; AASLD, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; AFEF, French Association for the Study of the Liver; AGA, American Gastroenterology Association; AISF, Italian Association for the Study of the Liver; ALEH, Latin American Association for the study of the liver; APASL, The Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver; APRI, AST to platelet ratio index; BASL, Belgian Association for the Study of the Liver; BSG, British Society of Gastroenterology; CSG, Chinese Society of Gastroenterology; DGVS, German Society of Gastroenterology, Digestive and Metabolic Diseases; EASL, European Association for the Study of the Liver; FIB-4, Fibrosis-4; INASL, India National Association for the Study of the Liver; JSG, Japanese Society of Gastroenterology; KASL, The Korean Association for the Study of the Liver; NFS, NAFLD fibrosis score; NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

NAFLD Fibrosis Score

The NAFLD fibrosis score (NFS) was developed by Angulo et al. in 2007 to assess for advanced fibrosis in patients with NAFLD. It uses six variables: age, presence of hyperglycemia, body mass index (BMI), platelet count, albumin, and the AST/ALT ratio.39 Advanced fibrosis is ruled out with a score of <−1.45 and ruled in with a score of >0.676. In their retrospective model, use of the NFS score would have avoided liver biopsy in 75% of patients with correct prediction in 90% of patients.39

Fourteen guidelines2,10,12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20,26,27,29 recommend the use of NFS. Eight guidelines2,10,12, 13, 14,16,20,29 recommend the cutoff values proposed by Angulo et al. AISF recommends a single cutoff of <−1.45 to rule out fibrosis.27 Patients with scores <−1.45 are recommended to repeat NITs in 1–3 years, and those with scores >−1.45 are recommended to pursue further workup for fibrosis. The Catalan guidelines and DGVS recommend a lower cutoff of <−1.4 in patients younger than 65 and a lower cutoff of <0.12 in patients 65 and older. The Catalan guidelines do not specify an upper cutoff and consider all patients with scores >−1.4 to be medium-to-high risk for fibrosis and recommend further testing with elastography.15,21 The DGVS recommends an upper cutoff of >0.67 to rule in advanced fibrosis.15, 21 Six other guidelines8,17, 18, 19,22,26 recommend NFS but do not specify cutoff values. The AACE recommends against using NFS in primary care settings as it overestimates fibrosis in patients with obesity and diabetes.9 Similarly, AFEF recommends avoiding the NFS in patients with diabetes, stating that approximately 80% of patients with hyperglycemia or diabetes have high or indeterminate NFS scores, which significantly overestimates the prevalence of advanced fibrosis in this population.29 The AGA clinical care pathway prefers FIB-4 over NFS, citing superior diagnostic accuracy in predicting advanced fibrosis. The NICE-UK guidelines do not comment on NFS (Table 2).11

AST to Platelet Ratio Index

The APRI was originally developed to predict significant fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients with hepatitis C40 and has since been shown to reliably predict fibrosis in patients with NAFLD.35,36,41 The formula is [[AST/upper limit of normal AST] × 100]/platelet count. Five guidelines (Egyptian guidelines, APASL, AGA, SBH, and EASL) recommended the use of APRI in NAFLD assessment. The Egyptian guidelines and APASL recommend a lower cutoff of <0.5 to rule out advanced fibrosis and an upper cutoff of >1.5 to rule in advanced fibrosis.10,13 The AGA recommends cutoffs of <0.48 and >1.34.11 Three guidelines8,18,26 recommend the use of APRI but do not specify cutoffs. Five guidelines2,14,16,17,21 do not recommend the APRI over other tests such as the NFS and FIB-4. The ALEH questions the accuracy of the APRI in NAFLD patients, citing a meta-analysis that showed superior performance of NFS and FIB-4 in detecting advanced fibrosis in NAFLD.2, 14, 16, 17, 21 Similarly, the AASLD, BASL, CSG, and DGVS recommend the NFS and FIB-4 over APRI in predicting advanced fibrosis in NAFLD (Table 2).2,16,17,21

Enhanced Liver Fibrosis Test

The ELF test is a panel that measures the levels of three serum markers of liver fibrosis: hyaluronic acid (HA), type III procollagen peptide (PIIINP), and tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase 1 (TIMP-1). This model estimates the rate of liver extracellular matrix metabolism which correlates with the severity of liver fibrosis. It was first proposed by as the “Original European Liver Fibrosis Test” in 2004 using the three aforementioned biomarkers along with patient age42 to estimate fibrosis in patients with chronic liver disease. In 2008, age was removed from the model and the algorithm was updated in a validation study that focused on patients with NAFLD. This new model was deemed the “Enhanced Liver Fibrosis Test” and was demonstrated to reliably detect advanced fibrosis in patients with NAFLD with an AUC of 0.9.43 The Siemens Healthineers medical device company later revised the algorithm using a different scale. Subsequent studies reported varying results using different manufacturer recommendations for cutoffs. A recent meta-analysis showed that the ELF test had a sensitivity of 93% and specificity of 34% at the lower cutoff of 7.7, and a sensitivity of 65% and specificity of 86% at the upper cutoff of 9.8. In low-prevalence populations, authors reported high NPV and lower PPV.44

Eight guidelines9,10,12,13,18,19,28,29 recommended the use of ELF as a second-line tool for fibrosis assessment. The AACE recommends cutoffs of <7.7 to rule-in fibrosis and >9.8 to rule-out fibrosis.9 The Egyptian guidelines recommend a single cutoff of <10.35.9, 10, 12, 13, 18, 19, 28, 29 The KASL recommends a single cutoff of <0.3576 citing the study by Guha et al., which is equivalent to <10.17 on the Siemens scale.12,43,44 The NICE-UK guidelines recommend a single cutoff of <10.51.9, 10, 12, 13, 18, 19, 28, 29 The ELF is recommended by APASL, EASL, BSG, and AFEF, but no cutoffs were specified.13,18,19,29 The BASL acknowledges the utility of the ELF but notes that given its use of nonroutine laboratory tests and lack of reimbursement, its use was limited in daily practice.16 The AASLD notes that the ELF had been approved for commercial use in Europe but states that it was not available for clinical use in the United States.2 Of note, 3 years after the AASLD guidelines were published, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the ELF for commercial use in August 2021. Similarly, the DGVS acknowledges that the ELF has a high NPV in ruling out advanced fibrosis, especially in populations with low NAFLD prevalence but states that further studies are needed to determine the use of this marker in primary care before it could be routinely recommended.21 The ELF is not mentioned in AISF, AGA, ALEH, Catalan guidelines, CSG, SBH, JSG, AAEH, and INASL (Table 3).8,11,14,15,17,20,22,26,27

Table 3.

Summary of Recommendations on the Use of the ELF and VCTE for Risk-Stratification in Patients With NAFLD.

| Recommendations | Guidelines |

|---|---|

| ELF | |

| Cutoff of <7.7 and >9.8 | AACE. (1) |

| Cutoff of <10.35 | Egyptian guidelines. (1) |

| Cutoff of <0.3576 (equivalent of 10.17 on the Siemens scale) | KASL. (1) |

| Cutoff of <10.51 | NICE-UK. (1) |

| ELF is recommended but did not specify cutoffs | APASL, EASL, BSG, AFEF. (4) |

| ELF is useful but limited by availability, and thus not recommended | BASL, AASLD, DGVS. (3) |

| ELF was not mentioned | AISF, AGA, ALEH, Catalan guidelines, CSG, SBH, JSG, DGVS, INASL (9) |

| VCTE | |

| Cutoff of <8 and >12 | AACE, AGA, DGVS. (3) |

| Cutoff of <8 | IASF, ALEH. (2) |

| Cutoff of <7.9 (M-probe), <7.2 (XL-probe) | BASL. (1) |

| Cutoff of <9.9 | AASLD. (1) |

| Cutoff of <10 and >15 | APASL. (1) |

| Cutoff of <8 and >18 | Catalan guidelines. (1) |

| Cutoff of <7.9 and >9.6 | AFEF. (1) |

| VCTE is recommended, but there is no acceptable threshold for diagnosis and the optimum pathway has not been determined | CSGS, EASL, BSG, INASL. (4) |

| VCTE is recommended but did not specify cutoff | Egyptian guidelines, KASL, JSG, AAEH. (4) |

| VCTE was not mentioned | NICE-UK. (1) |

Abbreviations: AACE, American Association of Clinical Endocrinology; AAEH, Asociación Española para el Estudio del Hígado; AASLD, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; AFEF, French Association for the Study of the Liver; AGA, American Gastroenterology Association; AISF, Italian Association for the Study of the Liver; ALEH, Latin American Association for the study of the liver; APASL, The Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver; BASL, Belgian Association for the Study of the Liver; BSG, British Society of Gastroenterology; CSG, Chinese Society of Gastroenterology; DGVS, German Society of Gastroenterology, Digestive and Metabolic Diseases; EASL, European Association for the Study of the Liver; ELF, enhanced liver fibrosis score; INASL, India National Association for the Study of the Liver; JSG, Japanese Society of Gastroenterology; KASL, The Korean Association for the Study of the Liver; NAFLD, Non Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease; NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; VCTE, vibration-controlled transient elastography.

Liver Stiffness Measurement: Vibration-controlled Transient Elastography

Several radiographic tools exist for the quantification of severity of hepatic fibrosis, including VCTE, SWE, and MR elastography. These tests were largely recommended as second or third-line modalities when first and second-line NITs resulted in indeterminate or high scores. Of these options, VCTE is the most widely used and the most frequently recommended. The VCTE is an US-based technique in which a probe generates a vibration that induces a shear wave that propagates through the liver. The US measures the wave velocity which correlates with liver stiffness; faster velocities correspond with increased liver stiffness. Two probes are available: the classic M probe and the XL probe which was developed for optimal use in patients with obesity. In a study by Eddowes et al., liver stiffness measurement values of <8.2 kPa excluded advanced fibrosis (fibrosis stage 3 or 4) with an NPV of >80%, and values of >12.1 predicted advanced fibrosis with a PPV of 76–88% in high prevalence populations, although the PPV for primary care populations was more variable.45 Similar to conventional US, VCTE has lower accuracy in obese patients.46 Conventional attenuation parameter is an available software add-on built into VCTE that estimates the propagation of US waves through the liver in decibels per meter, which corresponds with severity of steatosis.

Eighteen guidelines recommend use of VCTE.2,9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22,26,27,29 Three guidelines9,11,21 recommend cutoffs of <8 kPa to rule out advanced fibrosis and >12 kPa to rule in advanced fibrosis, with values of 8–12 being indeterminate. DGVS states that if the M and XL probes are used correctly, no adjustments to the cutoff values are required.9, 11, 21 The APASL recommends cutoffs of <10 and >15, the Catalan guidelines recommend cutoffs of <8 and >15, and the AFEF recommends cutoffs of <7.9 and >9.6.13,15,29 The AISF and ALEH recommend a single cutoff of <8 to rule out advanced fibrosis.14,27 The BASL recommends cutoffs of <7.9 (using M-probe) and <7.2 (using XL probe), and the AASLD recommends a single cutoff of <9.9.2,16 The CSG, BSG, and EASL recommend the use of VCTE but state that there is no consensus cutoff that should be used and that the optimum pathway has not been determined.17, 18, 19 The Egyptian guidelines, KASL, JSG, and INASL recommend VCTE but do not specify a cutoff.8,10,12,20 The AAEH recommends using VCTE in conjunction with conventional attenuation parameter to simultaneously assess degree of fibrosis and steatosis but does not specify a cutoff (Table 3).22

SWE is another US-based method to quantify fibrosis and is available as a software component on many modern US devices.21 However, SWE is less validated in NAFLD and only recommended as an alternative option to VCTE by two guidelines.12,13 MRE is the most accurate tool for fibrosis quantification but is limited by high cost and limited availability and is therefore recommended only in select cases or for research purposes and not in the routine clinical setting.

When to Get Liver Biopsy?

Despite its invasive nature and expensive cost, liver biopsy remains the only validated method to distinguish between NASH from NAFL, while also providing the ability to assess for other causes of liver injury. However, guidelines differ on the indications for liver biopsy in the assessment of NAFLD. The most common indications for biopsy were indeterminate or high results on NITs, assessment for other causes of liver disease, or high clinical suspicion for NASH or advanced fibrosis. Several guidelines disagreed on the role of liver biopsy in patients with high results on NITs. Seven guidelines recommend liver biopsy in patients with indeterminate or high NIT results to confirm fibrosis.2,9,11,16,18, 19, 20,26 The AAEH recommends liver biopsy to confirm NAFLD in patients with steatosis and metabolic comorbidities but did not provide a specific pathway to follow before pursuing biopsy.22 The Catalan guidelines state that liver biopsy is useful in indeterminant cases and recommends biopsy for indeterminate VCTE scores of 8–18 kPa or if there was clinical doubt in the diagnosis.15 They state that the primary diagnosis and evaluation of NAFLD should be based on NITs rather than liver biopsy. Similarly, the APASL states that if NITs are high, this is sufficient for management and liver biopsy is not needed.13 The AFEF states that liver biopsy is not required if both simple blood tests (FIB-4, NFS) and specialized blood tests (i.e., ELF) show advanced fibrosis.29 They recommend liver biopsy if results are likely to modify patient management. The INASL guidelines recommend liver biopsy for patients who are likely to have severe disease, with predictors of severity including age greater than 45, female gender, high APRI and NFS scores, and the presence of diabetes or metabolic syndrome.8 The KASL guidelines were less clear, recommending liver biopsy in patients suspected of having NASH, advanced fibrosis, or coexisting liver disease, but did not specify further.12 The BSG recommends liver biopsy if there was diagnostic uncertainty or inconclusive fibrosis staging using noninvasive methods, or if patients were candidates for pharmacologic therapy for NASH.2, 9, 11, 16, 18, 19, 20, 26

Discussion

While guidelines differ in threshold values and interpretation of NIT scores, they share a similar overarching approach to NAFLD assessment. Guidelines disagree on the utility of case-finding for NAFLD in high-risk groups, but most agree that risk factors primarily consist of diabetes, obesity, and metabolic syndrome. Due to the invasive nature of liver biopsy, more attention is being placed on NITs to assess for fibrosis. Most guidelines recommend a three-tiered system, in which US is used to screen for NAFLD in high-risk patients or those with abnormal liver function tests. If abnormal, simple scoring systems are calculated to assess for fibrosis, of which the FIB-4 is the most recommended but had the greatest variation in recommended cutoff values. The APRI was the least recommended with several guidelines noting its inferiority compared to the FIB-4 and NFS. However, because the NFS and APRI are calculated from routine lab values and clinical data, these tests can easily be incorporated into the assessment of NAFLD regardless. For indeterminate or high results, guidelines recommend more specialized testing, either via specialized blood tests such as the ELF or via radiographic modalities such as VCTE. Of the NITs, VCTE is widely considered to be the most accurate test for fibrosis assessment, aside from MRE which is not recommended for routine clinical use due to limitations in cost and availability. This tiered approach has been shown to improve efficiency in NAFLD assessment in the primary care setting, with AFEF noting that in patients who underwent a FIB-4–ELF pathway (stepwise progression of FIB-4 to ELF to specialist referral, with indeterminate or high results leading to progression in the clinical pathway), “unnecessary” specialist referrals were decreased by four-fold compared to general practitioners who did not follow this pathway. It is important to note that because the general population has a relatively low prevalence of advanced liver fibrosis compared to a hepatology clinic patient panel, the pretest probabilities of the NITs will be lower. Thus, when these NITs are applied toward the general population, the false-positive rate is likely to be higher compared to that of a hepatology clinic panel.

Guidelines largely agreed on the interpretation of low-risk and indeterminate-risk NIT scores. Low-risk NIT scores can reliably rule out advanced fibrosis, and most guidelines recommend following up with primary care, optimizing risk factors, and repeating NITs every 1–3 years. For indeterminate-risk NIT scores between the lower and upper cutoffs, most guidelines recommend proceeding with additional NITs, and if still indeterminate, to consider specialist referral for further evaluation, including liver biopsy if the diagnosis is uncertain. However, interpretation of high-risk NIT scores varied. Seven guidelines10,12, 13, 14,16,18,27 treat high-risk scores similarly to indeterminate risk-scores: proceeding with additional NITs and referring to specialists if indeterminate or high. However, APASL only recommends liver biopsy only in indeterminate cases, stating that high-risk scores on NITs are usually sufficient to guide management. Four guidelines9,11,15,19 recommend specialist referral for any high-risk NIT scores without need for additional work-up (i.e., a high FIB-4 score does not necessitate further assessment with ELF or elastography and can be referred directly to a specialist). The Catalan guidelines recommend liver biopsy only for indeterminate VCTE scores.8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 The JSG says to “consider” elastography or liver biopsy for indeterminate-risk scores and “recommends” elastography or liver biopsy for high-risk scores.20 The DGVS recommends specialist referral for elastography and further diagnostics for patients with indeterminate-risk or high-risk scores although they state that repeating NITs in 1 year is also an option for those with indeterminate-risk scores.21 The AFEF states that liver biopsy is not required if both simple tests (FIB-4, NFS) and specialized tests (ELF, elastography) result in high-risk scores.29 Four guidelines2,17,26,28 do not comment on high versus indeterminate-risk NIT scores.

There is notable variation in the reported prevalence of NAFLD worldwide, which can likely be attributed to regional differences in diet, lifestyle, and genetics. The global prevalence of NAFLD is estimated to be 24% with the highest rates reported in the Middle East (32%), followed by South America (31%), Asia (27%), the United States (24%), and Europe (23%).47 The reported prevalence was lowest in Africa (14%).47 While obesity is widely considered a strong risk factor for NAFLD development, NAFLD is still seen in high rates among populations with lower rates of obesity such as Asia. This phenomenon has been termed “lean NAFLD” and reflects the propensity for Asians to develop adverse metabolic events at comparatively lower BMIs. Despite having normal-range BMIs, these patients often have IR and exhibit features of metabolic syndrome. Lean NAFLD is estimated to account for 5–26% in Asian areas and 7–20% in Western areas.48 The AGA recommends that lean NAFLD be diagnosed in patients with NAFLD and BMI <25 for non-Asians and BMI <23 for Asians.49 Such heterogeneity in NAFLD epidemiology may contribute to the subtle differences in society guidelines as discussed above.

Recent studies suggest that certain NITs have lower accuracy in patients with diabetes. Boursier, et al. demonstrated that the prevalence of advanced liver fibrosis was two times higher in patients with diabetes compared to those without. As such, the number of missed cases due to false negative NIT results was significantly higher. Additionally, the diagnostic accuracy of all NITs, including the NFS, FIB-4 and VCTE, was lower in patients with diabetes compared to those without. To account for this confound, the authors proposed an alternative algorithm for the assessment of advanced fibrosis in patients with diabetes which bypasses the FIB-4 completely and proceeds directly to specialized tests such as the FibroMeterVCTE, a specialized test that combines both serum biomarkers and transient elastography.50

There are several limitations to our study. Our search was limited to guidelines written in English, including translations to English. Given the heterogeneity in NAFLD epidemiology, it is possible we may have missed guidelines that were tailored to a specific region and unavailable in English. However, our guidelines still represented a wide range of countries. We did not discuss less common types of NITs such as the Fatty Liver Index,27 BARD score,21 and Fibrotest29 as they were recommended by a much smaller number of guidelines. We limited our discussion to the screening, diagnosis, and assessment of NAFLD and did not examine strategies for treatment and monitoring for liver-related complications such as hepatocellular carcinoma, as this was beyond our scope of this review.

NFLD is a rising cause of chronic liver disease and its burden on the healthcare system continues to grow. NITs play a valuable role in the risk stratification of severe disease in patients with NAFLD and have the potential to limit specialist referrals and avoid unnecessary liver biopsies. Although guidelines disagree over the benefits of screening and the interpretation of NIT results, all guidelines recognize the utility of NITs and recommend their incorporation into the clinical assessment of NAFLD.

Credit authorship contribution statement

SS: Conceptualization, Project administration, Supervision, Visualization. KC, PF, AS, SS: Data curation. KC, PF, AS: Formal analysis. KC, PF, AS, SS: Investigation. KC, SS: Methodology. KC, PF, AS, SS: Validation. KC: Roles/Writing – original draft. KC, PF, AS, SS: Writing – review and editing.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have none to declare.

Funding

None.

References

- 1.Cheemerla S., Balakrishnan M. Global epidemiology of chronic liver disease. Clin Liver Dis. 2021;17:365–370. doi: 10.1002/cld.1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chalasani N., Younossi Z., Lavine J.E., et al. The diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: practice guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2018;67:328–357. doi: 10.1002/hep.29367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mavilia M. Mechanisms of progression in Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol Endosc. 2018;3 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harrison S.A., Gawrieh S., Roberts K., et al. Prospective evaluation of the prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and steatohepatitis in a large middle-aged US cohort. J Hepatol. 2021;75:284–291. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong R.J., Aguilar A., Cheung R., et al. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is the second leading etiology of liver disease among adults awaiting liver transplantation in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:547–555. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Estes C., Razavi H., Loomba R., Younossi Z., Sanyal A.J. Modeling the epidemic of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease demonstrates an exponential increase in burden of disease. Hepatology. 2018;67:123–133. doi: 10.1002/hep.29466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Antunes C., Azadfard M., Hoilat G.J., et al. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island (FL): 2022. Fatty Liver. [Updated 2021 Nov 7]https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441992/ (StatPearls [Internet]). Available from: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duseja A., Singh S.P., Saraswat V.A., et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and metabolic syndrome-position paper of the Indian National Association for the Study of the Liver, Endocrine Society of India, Indian College of Cardiology and Indian Society of Gastroenterology. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2015;5:51–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jceh.2015.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cusi K., Isaacs S., Barb D., et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinology clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in primary care and endocrinology clinical settings: co-sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) Endocr Pract. 2022;28:528–562. doi: 10.1016/j.eprac.2022.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fouad Y., Esmat G., Elwakil R., et al. The Egyptian clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of metabolic associated fatty liver disease. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2022;28:3–20. doi: 10.4103/sjg.sjg_357_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kanwal F., Shubrook J.H., Adams L.A., et al. Clinical care pathway for the risk stratification and management of patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterol. 2021;161:1657–1669. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.07.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kang S.H., Lee H.W., Yoo J.J., et al. Korean Association for the Study of the Liver (KASL). KASL clinical practice guidelines: management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2021;27:363–401. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2021.0178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eslam M., Sarin S.K., Wong V.W., et al. The Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of metabolic associated fatty liver disease. Hepatol Int. 2020;14:889–919. doi: 10.1007/s12072-020-10094-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arab J.P., Dirchwolf M., Álvares-da-Silva M.R., et al. Latin American Association for the study of the liver (ALEH) practice guidance for the diagnosis and treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Ann Hepatol. 2020;19:674–690. doi: 10.1016/j.aohep.2020.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caballeria L., Augustin S., Broquetas T., et al. Recommendations for the detection, diagnosis and follow-up of patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in primary and hospital care. Med Clín. 2019;153:169–177. doi: 10.1016/j.medcli.2019.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Francque S., Lanthier N., Verbeke L., et al. The Belgian association for study of the liver guidance document on the management of adult and paediatric non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2018;81:55–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fan J.G., Wei L., Zhuang H., National Workshop on Fatty Liver and Alcoholic Liver Disease, Chinese Society of Hepatology, Chinese Medical Association. Fatty Liver Disease Expert Committee, Chinese Medical Doctor Association Guidelines of prevention and treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Dig Dis. 2018;20:163–173. doi: 10.1111/1751-2980.12685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO) EASL-EASD-EASO clinical practice guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2016;64:1388–1402. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McPherson S., Armstrong M.J., Cobbold J.F., et al. Quality standards for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): consensus recommendations from the British Association for the Study of the Liver and British Society of Gastroenterology NAFLD Special Interest Group. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7:755–769. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(22)00061-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tokushige K., Ikejima K., Ono M., et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease/nonalcoholic steatohepatitis 2020. J Gastroenterol. 2021;56:951–963. doi: 10.1007/s00535-021-01796-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tacke F., Canbay A., Bantel H., et al. Updated S2k clinical practice guideline on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) issued by the German Society of Gastroenterology, Digestive and Metabolic Diseases (DGVS) AWMF. 2022:21–25. doi: 10.1055/a-1880-2388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aller R., Fernández-Rodríguez C., Lo Iacono O., et al. Consensus document, management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), clinical practice guidelines. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;41:328–349. doi: 10.1016/j.gastrohep.2017.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leoni S., Tovoli F., Napoli L., Serio I., Ferri S., Bolondi L. Current guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review with comparative analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:3361–3373. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i30.3361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Monelli F., Venturelli F., Bonilauri L., et al. Systematic review of existing guidelines for NAFLD assessment. Hepatoma Res. 2021;7:25. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhu J.Z., Hollis-Hansen K., Wan X.Y., et al. Clinical guidelines of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:8226–8233. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i36.8226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cotrim H.P., Parise E.R., Figueiredo-Mendes C., Galizzi-Filho J., Porta G., Oliveira C.P. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease Brazilian Society of Hepatology consensus. Arq Gastroenterol. 2016;53:118–122. doi: 10.1590/S0004-28032016000200013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in adults 2021: a clinical practice guideline of the Italian Association for the Study of the Liver (AISF), the Italian Society of Diabetology (SID) and the Italian Society of Obesity (SIO) Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis (NMCD) 2022;32:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2021.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Guideline Centre (UK) Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Assessment and Management. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boursier J., Guillaume M., Bouzbib C., et al. Non-invasive diagnosis and follow-up of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2022;46 doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2021.101769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mishra P., Younossi Z.M. Abdominal ultrasound for diagnosis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2716–2717. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saadeh S., Younossi Z.M., Remer E.M., et al. The utility of radiological imaging in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:745–750. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.35354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bril F., Ortiz-Lopez C., Lomonaco R., et al. Clinical value of liver ultrasound for the diagnosis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in overweight and obese patients. Liver Int. 2015;35:2139–2146. doi: 10.1111/liv.12840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sumida Y., Yoneda M., Hyogo H., et al. Validation of the FIB4 index in a Japanese nonalcoholic fatty liver disease population. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-12-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sterling R.K., Lissen E., Clumeck N., et al. Development of a simple noninvasive index to predict significant fibrosis in patients with HIV/HCV coinfection. Hepatology. 2006;43:1317–1325. doi: 10.1002/hep.21178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee J., Vali Y., Boursier J., et al. Prognostic accuracy of FIB-4, NAFLD fibrosis score and APRI for NAFLD-related events: a systematic review. Liver Int. 2021;41:261–270. doi: 10.1111/liv.14669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Amernia B., Moosavy S.H., Banookh F., Zoghi G. FIB-4, APRI, and AST/ALT ratio compared to FibroScan for the assessment of hepatic fibrosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in Bandar Abbas, Iran. BMC Gastroenterol. 2021;21:453. doi: 10.1186/s12876-021-02038-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shah A.G., Lydecker A., Murray K., Tetri B.N., Contos M.J., Sanyal A.J., Nash Clinical Research Network Comparison of noninvasive markers of fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:1104–1112. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.05.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McPherson S., Hardy T., Dufour J.F., et al. Age as a confounding factor for the accurate non-invasive diagnosis of advanced NAFLD fibrosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:740–751. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Angulo P., Hui J.M., Marchesini G., et al. The NAFLD fibrosis score: a noninvasive system that identifies liver fibrosis in patients with NAFLD. Hepatology. 2007;45:846–854. doi: 10.1002/hep.21496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wai C.T., Greenson J.K., Fontana R.J., et al. A simple noninvasive index can predict both significant fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2003;38:518–526. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kruger F.C., Daniels C.R., Kidd M., et al. APRI: a simple bedside marker for advanced fibrosis that can avoid liver biopsy in patients with NAFLD/NASH. S Afr Med J. 2011;101:477–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosenberg W.M., Voelker M., Thiel R., et al. Serum markers detect the presence of liver fibrosis: a cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1704–1713. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.08.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guha I.N., Parkes J., Roderick P., et al. Noninvasive markers of fibrosis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: validating the European Liver Fibrosis Panel and exploring simple markers. Hepatology. 2008;47:455–460. doi: 10.1002/hep.21984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vali Y., Lee J., Boursier J., et al. Enhanced liver fibrosis test for the non-invasive diagnosis of fibrosis in patients with NAFLD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hepatol. 2020;73:252–262. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eddowes P.J., Sasso M., Allison M., et al. Accuracy of fibroscan controlled attenuation parameter and liver stiffness measurement in assessing steatosis and fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:1717–1730. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wong V.W., Vergniol J., Wong G.L., et al. Diagnosis of fibrosis and cirrhosis using liver stiffness measurement in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2010;51:454–462. doi: 10.1002/hep.23312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Younossi Z., Anstee Q.M., Marietti M., et al. Global burden of NAFLD and NASH: trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;15:11–20. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2017.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Younes R., Bugianesi E. NASH in lean individuals. Semin Liver Dis. 2019;39:86–95. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1677517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Long M.T., Noureddin M., Lim J.K. Aga clinical practice update: diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in lean individuals: expert review. Gastroenterology. 2022 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.06.023. S0016-S5085(22)00628-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boursier J., Canivet C.M., Costentin C., et al. Impact of type 2 diabetes on the accuracy of noninvasive tests of liver fibrosis with resulting clinical implications [published online ahead of print, 2022 Mar 11] Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.02.059. S1542-S3565(22)00248-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]