Abstract

Glioblastoma (GBM) is a highly aggressive tumor with a devastating impact on quality-of-life and abysmal survivorship. Patients have very limited effective treatment options. The successes of targeted small molecule drugs and immune checkpoint inhibitors seen in various solid tumors have not translated to GBM, despite significant advances in our understanding of its molecular, immune, and microenvironment landscapes. These discoveries, however, have unveiled GBM’s incredible heterogeneity and its role in treatment failure and survival. Novel cellular therapy technologies are finding successes in oncology and harbor characteristics that make them uniquely suited to overcome challenges posed by GBM, such as increased resistance to tumor heterogeneity, modularity, localized delivery, and safety. Considering these advantages, we compiled this review article on cellular therapies for GBM, focusing on cellular immunotherapies and stem cell-based therapies, to evaluate their utility. We categorize them based on their specificity, review their preclinical and clinical data, and extract valuable insights to help guide future cellular therapy development.

Keywords: cell therapy, glioblastoma, immunotherapy, stem cell therapy, tumor heterogeneity

Glioblastoma (GBM), the most common primary CNS malignancy in adults, remains with very limited treatment options and abysmal outcomes despite leaps in the understanding of the disease.1 The WHO’s 2016 re-classification of GBM based on IDH mutation status highlights a turning point in the field by recognizing that molecular heterogeneity of histologically similar tumors may represent distinct tumorigenesis pathways with clinical and therapeutic implications.2 Advances in the molecular characterization of GBM, with large contributions from The Cancer Genome Atlas, have underscored its vast heterogeneity and tied it to patient-centric endpoints.3–7 Although the inter- and intratumor variation has been significantly deconvoluted in recent decades, the only 2 newly approved treatments with overall survival (OS) benefit over this time frame, the Stupp regimen and the innovative tumor-treating fields, rely on traditional tenets of tumor biology.8–10 A wide spectrum of rationally designed therapies, including targeted small molecules, anti-angiogenic biologics, immune checkpoint inhibitors, antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), and oncolytic viruses have not demonstrated clinically translatable benefit.11–15

Cell-based therapies are an exciting new approach with the potential to revolutionize cancer treatment. These refer to the application of living cells to reduce tumor burden and improve clinical outcomes, both directly and indirectly. In 1994, the first adoptive cell transfer therapy, developed by Rosenberg’s group, involved the peripheral administration of autologous tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and high-dose interleukin 2 (IL2) to patients with metastatic melanoma.16 A post-hoc analysis of patients with untreated brain metastases showed that this treatment is associated with up to 41% intracranial complete responsive rate.17 The first dendritic cell (DC) vaccine was generated in 1995 for melanoma by pulsing DCs with a synthetic MAGE-1 peptide, which induced T-cell-mediated anti-tumor response.18 Sipuleucel-T (Dendreon Corp), the first FDA-approved DC vaccine, emerged in 2010 for the treatment of prostate cancer. In 2011, T cells modified to express the CD19-specific chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) were administered in a first-in-human trial in chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients, resulting in long-term remission.19 This work, in conjunction with the 2018 Nobel Prize awarded to Drs. James Allison and Tasuku Honjo for their work on immune checkpoints, spurred extensive development of cellular, biologic, and other novel immunotherapies. CAR T cells, for example, have so far been approved for hematologic malignancies, with 4 CD19-specific products approved for various non-Hodgkin lymphomas and/or acute leukemias and 2 BCMA-specific products for multiple myeloma. Also, in 2017, genetically engineered neural stem cells (NSC) were first used in humans as tumor-homing drug delivery vehicles in glioma patients (NCT01172964).

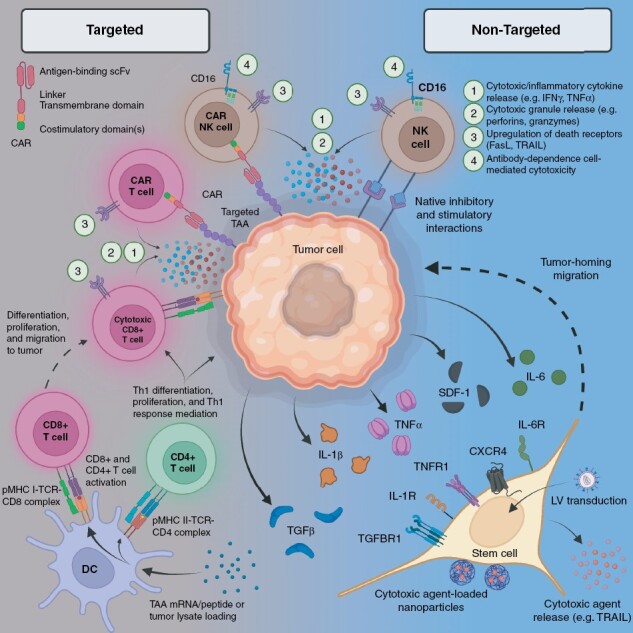

In this report, we review current literature on stem cell and leukocyte-based therapies for GBM and highlight their promises and limitations. With heterogeneity being a central tenet of GBM pathophysiology, treatment failure, and patient outcomes, we frame the current cell-based therapeutics based on their “targeted” or “non-targeted” mechanism of action, where “targeted” refers to a modality that utilizes tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) for its specificity, while “non-targeted” encompasses all other modalities (Figure 1). Our goal is to leverage such juxtaposition to elucidate the link between heterogeneity and clinical end-points, extract valuable therapeutic lessons to guide future clinical testing, and accelerate the development of effective cell-based technologies.

Figure 1.

Mechanisms of anti-tumor activity in cell therapies. CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; CXCR, C-X-C motif chemokine receptor; DC, dendritic cell; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; LV, lentiviral vector; MHC, major histocompatibility complex; NK, natural killer; TAA, tumor-associated antigen; TCR, T cell receptor; TGF, transforming growth factor; Th, T helper; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; TRAIL, tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand; scFv, single-chain variable fragment; SDF, stromal cell-derived factor.

Non-targeted Approaches

Non-targeted cell-based therapies are antigen-naive approaches—a unique property that provides some resistance to inter- and intra-tumor TAA heterogeneity. Rather than targeting a specific antigen, non-targeted cell-based therapeutics rely on inflammatory signals to reach their destination, including pro-inflammatory cytokines like tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), IL1, IL6, IL8, transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ), and interferon-gamma (IFNγ), which also drives the C-X-C chemokine receptor (CXCR) axis.20 CXCR-expressing cells follow gradients of interferon-inducible C-X-C ligands (CXCLs) including CXCL-1, CXCL-2, and CXCL-12 which are overexpressed in GBM.21 Tumor-expressed growth factors and matrix metalloproteinases can also serve as attractants for non-targeted therapy. Here, we review non-targeted approaches that utilize stem cells and natural killer (NK) cells.

Stem Cells

Stem cells are defined by 2 unique properties: self-renewal and differentiation. Certain stem cell types have restricted lineages, while others possess pluripotent capacity. Additionally, a subset of stem cells including MSCs, HSCs, and NSCs have tissue-specific trafficking capacity, a requirement for tissue regeneration and hematopoiesis.22,23 NSCs display extensive tropism to gliomas, migrating toward outgrowing microsatellites.24 This tropism is thought to rely heavily on interactions between stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1) and its corresponding receptor CXCR4.25,26 Stem cells lack intrinsic anti-tumor activity, but they have been used to deliver a wide variety of therapeutics including bioactive proteins, oncolytic viruses, cytokines, antibodies, nanoparticles, and other cytotoxic agents. MSCs, HSCs, NSCs, and induced NSCs (iNSC) have been explored in preclinical animal studies as described below.

MSCs

One of the first types of stem cell-based therapy in GBM was MSCs. In 2004, Nakamura and colleagues demonstrated that MSCs engineered to express human IL2 home to glioma tumor cells on the opposite side of rat brains, extending survival by 10 days.27 Another therapeutic application utilized MSCs expressing herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase (HSV-TK) with the adjuvant pro-drug ganciclovir (GCV) to inhibit tumor growth by 86%.28 HSV-TK converts GCV to a toxic metabolite that allows for selective elimination of TK+ cells; TK has been shown to correlate with the proliferative activity of tumor cells.29 MSCs have also been used as delivery vehicles for drug-loaded nanoparticles. Intravenous injection of MSCs containing paclitaxel-loaded nanoparticles resulted in a 4-fold increase in therapeutic index compared to temozolomide (TMZ), a common first line treatment for GBM.30

HSCs

Similar to MSCs, research has shown that HSCs migrate to tumor cells based on signaling from TGFβ and SDF-1α.31 Noyan et al. demonstrated the potential utility of HSCs by transplanting bone marrow with engineered HSCs prior to subcutaneous injection of glioma cells, significantly limiting tumor growth.32 Similarly, Flores et al. demonstrated that HSC transplants with myeloablative or non-myeloablative conditioning augment anti-tumor immunity synergistically with adoptively transferred tumor-specific T cells and RNA-pulsed DC vaccines.33 Preclinical results such as these are promising, but more investigation is necessary to confirm that HSC-based therapy is safe and effective.

NSCs

Aboody et al. was among the first to generate therapeutic NSCs for the treatment of GBM, using NSCs armed with cytosine deaminase (CD), which converts the adjuvant prodrug 5-flucytosine (5-FC) into the potent antineoplastic agent 5-fluorouracil.34 They used a v-myc-immortalized human NSC line, encoding CD to demonstrate that co-administration with 5-FC resulted in a 3-fold reduction in tumor volume. NSCs retained tumor tropism in mice despite pre-treatment with radiation or dexamethasone, 2 clinically relevant therapies, demonstrating their resilience to radio- and chemotherapy. Another application of NSC therapy engages adaptive immune cells rather than small molecule drugs. Katarzyna et al. used NSCs engineered to secrete bispecific T cell engagers to stimulate anti-glioma activity in T cells and induce cytokine production in exhausted tumor-associated lymphocytes.35 When administered to mice bearing IL13 receptor alpha 2-expressing (IL13RA2) patient-derived xenografts, modified NSCs increased survival by 67%. NSCs have also been used to improve retention and delivery of nanoparticles in glioma therapy.36 Four days after intracranial injection, 40% of streptavidin-conjugated nanoparticles surface-coupled to biotinylated NSCs were retained compared to 7% of free-nanoparticle suspensions. Additionally, 43% of nanoparticle-conjugated NSCs injected into the brain redistributed to the contralateral tumor site compared to free-nanoparticle suspensions. Notably, if these NSC-coupled nanoparticles were used to deliver TMZ, over 2.5 billion cells would be required to reach clinically relevant levels (120–135 mg). This number of cells would require an injection volume of at least 25 mL to prevent overconcentration, which may limit possible injection routes.

iNSCs

Induced NSCs are generated artificially via transdifferentiation of somatic cells. A key benefit of iNSCs is that they do not form teratomas, unlike pluripotent or embryonic stem cells.37 Additionally, since iNSCs are manufactured from a patient’s own cells, they do not provoke an immune response like allogeneic stem cells.38 Bagó et al. showed that iNSCs engineered to secrete TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL), a potent anti-tumor protein, retained their capacity to differentiate and induced apoptosis in co-cultured GBM cell lines.39 In another study, TRAIL-engineered iNSCs were shown to decrease the growth of solid orthotopic xenografts by 250-fold in 3 weeks and increase median survival by 27 days.40 They also engineered iNSCs to express HSV-TK, which when combined with GCV reduced the size of patient-derived GBM xenografts 20-fold and increased median survival by 30 days. Lastly, as a bridge to clinical therapy, Bago’s group implanted HSV-TK-engineered iNSCs into the postoperative surgical resection cavity, which delayed residual GBM growth 3-fold and increased median survival by 14 days.40

Clinical Studies with Stem Cells in GBM

Translation of preclinical stem cell therapy to clinical development is still in its infancy with the earliest clinical trial launched in 2010. Only a handful of Phase 1 trials have since been completed (Tables 1 and 2). Two active Phase 1 clinical trials are using genetically engineered MSCs against GBM. The first trial utilizes Ad5-DNX-2401, a brain tumor selective oncolytic adenovirus, to generate modified MSCs as a novel intra-arterial therapy for patients with recurrent high-grade gliomas (NCT03896568). The second trial utilizes CD-armed MSCs for intra-tumoral delivery in recurrent GBM (NCT04657315). Another Phase 1/2 trial is recruiting patients to receive IFNα-secreting HSCs (NCT03866109), which have been shown to improve immune activation in the tumor microenvironment (TME) and reduce protumoral gene expression in tumor-associated macrophages.41 Phase 1 NSC trials utilizing the CD/5-FC suicide gene therapy system have also been completed (NCT01172964, NCT02015819). Intracerebrally administered CD-modified NSCs with adjuvant 5-FC stabilized tumor growth in 3 of 16 patients (14 GBM, 2 non-GBM glioma) for 4 to 5 months.42 Another completed Phase 1 NSC trial utilized an adenoviral vector encoding the survivin promoter that binds heparan sulfate proteoglycans (CRAd-Survivin-pk7) to generate modified NSCs as a neoadjuvant virotherapy in conjunction with chemoradiotherapy.43 CRAd-Survivin-pk7 has previously been shown to greatly enhance anti-tumor efficacy in an experimental glioma model.44 Induced NSCs have not yet reached clinical trials, but efforts to translate therapies with this new cell type are underway.

Table 1.

Completed Cell Therapy Clinical Trials for GBM

| Cell Type | Trial Identifier | Phase | Intervention | Delivery | Enrollment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAR-T cell | |||||

| NCT01454596 | 1/2 | EGFRvIII | IV | 18 | |

| NCT03726515 | 1 | EGFRvIII | Unspecified | 7 | |

| NCT01109095 | 1 | HER2 | IV | 16 | |

| NCT00730613 | 1 | IL13RA2 | ICa | 3 | |

| DC vaccine | |||||

| NCT02820584 | 1 | Autologous GSC lysate | Unspecified | 20 | |

| NCT00890032 | 1 | Autologous GSC mRNA | ID | 50 | |

| NCT00846456 | 1/2 | Autologous GSC mRNA | ID | 20 | |

| NCT00068510 | 1 | Autologous tumor lysate | ID | 28 | |

| NCT01213407 | 2 | Autologous tumor lysate | IN | 87 | |

| NCT00576537 | 2 | Autologous tumor lysate | SC | 50 | |

| NCT01006044 | 2 | Autologous tumor lysate | SC | 26 | |

| NCT00045968 | 3 | Autologous tumor lysate | ID | 348 | |

| NCT01808820 | 1 | DCs followed by tumor lysate boost | ID | 20 | |

| NCT00323115 | 2 | Autologous tumor-DC coculture | IN | 11 | |

| NCT02366728 | 2 | CMV pp65-LAMP mRNA | ID | 64 | |

| NCT00639639 | 1 | CMV pp65-LAMP mRNA | ID | 42 | |

| NCT00626483 | 1 | CMV pp65-LAMP mRNA | ID | 34 | |

| NCT00693095 | 1 | CMV pp65-LAMP mRNA | ID | 23 | |

| NCT02529072 | 1 | CMV pp65-LAMP mRNA | ID | 6 | |

| NCT03615404 | 1 | CMV pp65-LAMP mRNA | Unspecified | 11 | |

| NCT02010606 | 1 | GBM cell line lysate | Unspecified | 39 | |

| NCT01171469 | 1 | GSC cell line | ID | 8 | |

| NCT02049489 | 1 | Purified CD133 peptides | ID | 20 | |

| NCT01280552 | 2 | Synthetic tumor peptides | ID | 124 | |

| NCT00576641 | 1 | Synthetic tumor peptides | ID | 22 | |

| NCT00612001 | 1 | Synthetic tumor peptides | Unspecified | 8 | |

| NSC | |||||

| NCT02062827 | 1 | CD/5-FC | IC | 16 | |

| NCT01172964 | 1 | CD/5-FC | IC | 15 | |

| NCT03072134 | 1 | CRAd-Survivin-pk7 | IT | 13 |

CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; CD, cytosine deaminase; CMV, cytomegalovirus; DC, dendritic cell; EGFRvIII, epidermal growth factor receptor variant III; FC, flucytosine; GBM, glioblastoma; GSC, glioma stem cell; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; IC, intracranial; ICa, intracavitary; ID, intradermal; IL13RA2, interleukin 13 receptor alpha 2; IN, intranodal; IT, intra-tumoral; IV, intravenous; LAMP, lysosome-associated membrane glycoprotein; SC, subcutaneous.

Table 2.

Ongoing, Suspended, and Terminated Cell Therapy Clinical Trials for GBM

| Cell Type | Trial Identifier | Phase | Intervention | Delivery | Est. Enrollment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAR-T cell | |||||

| NCT04077866 | 1/2 | B7H3 | ICV or IT | 40 | |

| NCT05474378 | 1 | B7H3 | ICV+/-IT | 39 | |

| NCT05366179 | 1 | B7H3 | ICV | 36 | |

| NCT05241392 | 1 | B7H3 | ICV or ICa | 30 | |

| NCT04385173 | 1 | B7H3 | ICV or IT | 12 | |

| NCT05577091 | 1 | CD44+CD133 | IT | 10 | |

| NCT04045847 | 1 | CD147 | ICa | 31 | |

| NCT05627323 | 1b | Chlorotoxin | IT+ICV | 42 | |

| NCT04214392 | 1 | Chlorotoxin | ICV vs. ICV+IT | 30 | |

| NCT05063682 | 1 | EGFRvIII | ICV | 10 | |

| NCT03283631 | 1 | EGFRvIII | IT | 2 | |

| NCT05660369 | 1 | EGFRvIII | IV | 21 | |

| NCT02844062 | 1 | EGFRvIII | IV | 20 | |

| NCT02209376 | 1 | EGFRvIII | IV | 11 | |

| NCT02664363 | 1 | EGFRvIII | Unspecified | 3 | |

| NCT04661384 | 1 | IL13RA2 | ICV | 30 | |

| NCT02208362 | 1 | IL13RA2 | ICV and/or IT and/or ICa | 92 | |

| NCT04003649 | 1 | IL13RA2 | ICV or IC | 60 | |

| NCT05131763 | 1 | NKG2DL | IV or IA | 3 | |

| NCT04717999 | 1 | NKG2DL | ICV | 20 | |

| NCT02937844 | 1 | PDL1 | IV | 20 | |

| DC vaccine | |||||

| NCT01957956 | 1 | Allogenic tumor lysate | ID | 21 | |

| NCT03360708 | 1 | Allogenic tumor lysate | ID | 20 | |

| NCT04888611 | 2 | Autologous GSC antigens | Unspecified | 40 | |

| NCT03548571 | 2/3 | Autologous GSC mRNA + survivin, hTERT mRNA | ID | 60 | |

| NCT03400917 | 2 | Autologous TAAs | Unspecified | 55 | |

| NCT04115761 | 2 | Autologous tumor antigens | IN | 24 | |

| NCT05100641 | 3 | Autologous tumor antigens | SC | 726 | |

| NCT04523688 | 2 | Autologous tumor homogenate | ID | 28 | |

| NCT03395587 | 2 | Autologous tumor lysate | ID | 136 | |

| NCT03879512 | 1/2 | Autologous tumor lysate | ID | 25 | |

| NCT01204684 | 2 | Autologous tumor lysate | IM | 60 | |

| NCT04201873 | 1 | Autologous tumor lysate | IM | 40 | |

| NCT04801147 | 1/2 | Autologous tumor lysate | Unspecified | 100 | |

| NCT04388033 | 1/2 | Autologous tumor-DC fusion | Unspecified | 10 | |

| NCT02465268 | 2 | CMV pp65-LAMP mRNA | ID | 175 | |

| NCT03688178 | 2 | CMV pp65-LAMP mRNA | ID | 112 | |

| NCT03927222 | 2 | CMV pp65-LAMP mRNA | ID | 48 | |

| NCT04963413 | 1 | CMV pp65-LAMP mRNA | Unspecified | 10 | |

| NCT02546102 | 3 | Synthetic tumor peptides | ID | 414 | |

| NCT04968366 | 1 | Tumor neoantigen peptides | ID | 10 | |

| NCT04552886 | 1 | Unknown | Unspecified | 24 | |

| NCT02649582 | 1/2 | WT1 mRNA | ID | 20 | |

| MSC | |||||

| NCT03896568 | 1 | Ad5-DNX-2401 | IA | 36 | |

| NCT04657315 | 1 | CD/5-FC | IT | 10 | |

| NK and CAR-NK cells | |||||

| NCT04254419 | 1 | N/A | IT | 24 | |

| NCT05108012 | 1 | N/A | IT | 5 | |

| NCT04489420 | 1 | N/A | IT vs. IV | 3 | |

| NCT00909558 | 1 | N/A | Unspecified | 24 | |

| NCT03383978 | 1 | Anti-HER2 CAR | IC | 30 | |

| NCT04991870 | 1 | TGFBR2-/NR3C1- | IT | 25 | |

| NSC | |||||

| NCT02192359 | 1 | hCE1m6 | IC | 53 |

CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; CD, cytosine deaminase; DC, dendritic cell; EGFRvIII, epidermal growth factor receptor variant III; FC, flucytosine; GSC, glioma stem cell; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; hCE1m6, human carboxylesterase; IA, intra-arterial; IC, intracranial; ICa, intracavitary; ICV, intracranioventricular; ID, intradermal; IM, intramuscular; IL13RA2, interleukin 13 receptor alpha 2; IN, intranodal; IT, intra-tumoral; IV, intravenous; LAMP, lysosome-associated membrane glycoprotein; NK, natural killer; NR3C1, nuclear receptor subfamily 3 group C member 1; NSC, neural stem cell; PDL1, programmed death-ligand 1; SC, subcutaneous; TAA, tumor-associated antigen; TGFBR2, transforming growth factor beta receptor 2; WT1, Wilms tumor 1.

NK Cells

NK cells are innate immune cells with cytotoxic activity against virally infected cells and tumor cells. Their activation relies on a balance between antigen-independent activating (eg, NKp30, NKG2D) and inhibitory (eg, killer Ig-like receptors [KIRs], CD94/NKG2A) interactions with the target cells, with anti-tumor mechanisms including granzyme and perforin release, inflammatory cytokine release, CD16-mediated antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity, and death receptor-induced apoptosis.45 NK cells are also stratified by the relative expression of CD56 and CD16, where CD56 expression is positively associated with cytokine release and inversely associated with cytotoxicity. IFNγ release is typical for both all NK cells, but it is especially crucial for CD56hi NK cells in connecting the adaptive and innate immune systems by priming antigen presenting cells (APCs) and T cells in secondary lymphoid tissue.46

Multiple protocols have been implemented to isolate NK cells from peripheral blood or cord blood and expand them ex vivo to generate cell products for clinical use. Studies show that patients may not respond to autologous NK cells due to inhibitory interactions between tumor human leukocyte antigen (HLA) and NK cells’ KIRs, and the immunosuppressive TME.47 However, allogeneic NK cells have anti-tumor activity and, unlike T cells, do not cause graft-versus-host disease in transplant recipients, indicating the potential for an “off-the-shelf” therapy.48,49 In light of this and NK cells data in hematologic malignancies, there is interest in developing approaches that circumvent inhibitory TME effects to maximize cytotoxicity against solid tumors. One such strategy involves producing NK cells from iPSCs because they do not express KIRs.50

Moreover, Rezvani and colleagues reported that allogeneic NK cells show cytotoxic activity against glioma stem cells (GSCs) in vitro while sparing normal astrocytes.51 Tanaka’s group demonstrated that adding TMZ to human peripheral blood mononuclear cell-derived NK cells triggers apoptosis in both TMZ-sensitive and TMZ-resistant GBM cell lines in vitro.52 Along similar lines, Navarro et al. showed that pre-treatment of GBM cells with the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib improved NK cell cytotoxicity in vivo.53

Clinical Studies with NK Cells in GBM

There are a few NK-based therapies undergoing clinical trials for GBM, and none have reported data yet. NK cell adoptive transfer has not yet led to meaningful clinical responses in patients with non-GBM solid tumors.54 It is currently thought that these lackluster results could be due to poor NK tumor infiltration; indeed, improved NK cell infiltration into various solid tumors (including GBM) has been shown to improve prognosis.55

Targeted Approaches

Targeted cell-based therapeutics for GBM encompass those modalities that are rationally designed to target TAAs that are prespecified or undetermined. Target selection is crucial as the antigen load must be significant enough to stimulate a clinically significant immune response, low enough to avoid secondary neurotoxicity, specific enough to minimize on-target, off-tumor effects, and persistently expressed to maintain the treatment’s activity. Ideal targets are rare, yet cancer-testis antigens, oncogenic viral proteins, tumor neoantigens, and some native proteins harbor these characteristics to a large extent.56 While other groups extensively reviewed CAR therapies for GBM, we will focus on CAR therapies that are novel or completed or are undergoing clinical trials, as well as DC vaccines in this section.57

CAR-engineered Leukocytes

CARs are fusion proteins with a monoclonal antibody-derived extracellular, antigen-binding single chain variable fragment (scFv) that is coupled with CD3ζ receptor complex signaling moieties and costimulatory domains. Upon expression on immune cells such as T cells and NK cells, CARs redirect the cells’ antigen specificity toward surface TAAs and activate a cytolytic program (Figure 1). More recently, CAR macrophages have been designed to redirect macrophages to phagocytose tumor cells.58 The critical TAA selection in CAR design is particularly complicated in GBM by the vast heterogeneity and delicate localization in the CNS. We listed some of the most studied CAR targets in GBM in both preclinical and clinical trials below (Tables 1 and 2).

Clinical Studies with CAR-T Cells and CAR-NK Cells in GBM

IL13RA2

IL13RA2 has been shown to be selectively overexpressed in over 50% of GBM samples and it is associated with a poorer prognosis.59 In a Phase 1 trial of first generation IL13RA2-targeting CAR CD8+ cytotoxic lymphocytes, Brown et al. treated 3 patients with 11-12 intra-cavitary doses delivered post-resection of recurrent or refractory high-grade gliomas. They showed safety and evidence of anti-tumor activity, including elimination of distant foci, with survival, which includes post-progression treatment, ranging from 8.6 to 13.9 months post-relapse.59 In a separate patient with multifocal leptomeningeal disease, the group modified their CAR into a second-generation CAR with 4-1BB costimulatory domain and an altered IgG4-Fc linker to minimize non-specific Fc-receptor interactions. Remarkably, intracavitary CAR-T delivery resulted in local tumor regression, while subsequent intraventricular delivery led to complete radiographic regression of all intracranial and spinal cord lesions. Unfortunately, recurrence of antigen-negative tumor occurred after 7.5 months.60 Additionally, the same group later demonstrated in vitro that IL13Rα2-specific CAR CD4+ T cells have superior efficacy and persistence compared to CD8+ T cells, highlighting the importance of cell product selection.61

EGFRvIII

Epidermal growth factor receptor variant III (EGFRvIII) is a constitutively active form of EGFR expressed in up to 30% of GBM cells with minimal-to-no expression in normal tissue.5 Multiple groups have demonstrated the ability of EGFRvIII-directed CAR-T cells to effectively eliminate GBM tumor cells in preclinical studies.62 Two clinical trials (NCT02209376, NCT01454596) assessing intravenous delivery of these CAR-T cells in GBM did not find objective radiographical responses or improvement in patient outcomes.63,64 This may be partially explained by spontaneous antigen loss, as was seen in 59% of evaluable patients in the control arm in a Phase 3 trial of the EGFRvIII-based peptide vaccine rindopepimut.65 Regardless, O’Rourke and colleagues showed evidence of variable CAR-T cell trafficking to the tumor with on-target, on-tumor effects that interestingly led to dramatic increase in both clonotypic T cell diversity and immunosuppressive molecules, as well as peripheral blood persistence lasting about 1 month.63 Goff’s group demonstrated CAR-T cell persistence up to 200 days post-infusion correlating with initial dose but not with survival. Surprisingly, although no patients showed objective responses, 2 patients survived for ~13 months and one patient remained alive at 59 months despite progression after 12.5 months at the relatively lowest fraction of CAR in the final infused product. It is curious that the surviving extreme outlier does not appear to have uniquely favorable prognosis factor profile among those measured or uniquely elevated target antigen load; extensive investigation of such outliers may shed light on favorable patient, tumor, cell product, and/or protocol characteristics. Given the exceptional survival, it is also worth considering that it was pseudo-progression that was observed at 12.5 months. This group also revealed post-infusion pulmonary toxicity, including one treatment-related death, at the highest treatment dose.64

HER2

Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) has been found to be overexpressed in multiple cancers, including GBM, and preclinical models with HER2-specific CAR-T cells showed antitumor activity in GBM models.66,67 There is a single completed clinical trial of HER2 CAR-T cells in GBM (NCT01109095), in which virus-specific CD8+ T cells were modified with HER2-specific second generation CAR given intravenously to 17 patients without lymphodepletion.68 While most patients passed after partial response or a period of stable disease, 3 patients notably are alive with stable disease at the time the data was published, with 36 to 41 months survival from the time of diagnosis—a detailed analysis of these exceptional survivors may yield testable hypotheses to inform subsequent trials. Importantly, the CAR-T cells were detected in the blood up to 12 months post-treatment. This highlights the potential for prolonged CAR-T persistence with durable efficacy, along with the potential for non-invasive administration. Furthermore, there is an ongoing clinical trial investigating intracranial delivery of HER2-directed CAR-NK cells with and without ezabenlimab (NCT03383978), with preliminary data showing no dose-limiting toxicities at the lowest two doses delivered.69

Novel Targets for CAR Immune Cells in GBM

B7H3

B7H3 is a type I transmembrane protein with an unknown receptor that is part of the B7 superfamily. It has been shown to be overexpressed in a wide variety of solid tumors and their vasculature, including GBM, with minimal expression in normal tissue.70–72 It is a particularly attractive target for immunotherapy due to its high, specific, and widespread expression within tumors and across GBM patients.70,73 Data from our group and Tang X et al. demonstrate that B7H3-specific CAR-T cells can effectively target GBM cell lines and patient-derived neurospheres in vitro and in vivo, as well as patient-derived xenograft in vivo. Furthermore, we demonstrated that the expression of B7H3 is higher and less variable across tumors relative to other CAR-T targets such as IL13RA2, HER2, and Eph receptor A2 (EPHA2). Five clinical trials assessing B7H3 CAR-T cells in GBM are underway (NCT05366179, NCT05474378, NCT04385173, NCT04077866, NCT05241392).

CSPG4

Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan-4 (CSPG4) is a transmembrane glycoprotein with a large extracellular portion that binds various proteins to shape the interstitiumvia growth factors, matrix metalloproteinases, and extracellular matrix.74 It is overexpressed in a wide spectrum of tumors, as well as in normal epidermal stem cells, mesenchymal stem cells, melanocytes, and smooth muscle cells.75 Our group and others demonstrated that CSGP4-directed CAR-T cells are able to efficiently target CSPG4-expressing tumor cells in preclinical studies, including GBM and GSCs.76,77 Furthermore, we showed that CSPG4 on neurospheres, but not other TAAs, is upregulated in vivo by tumor-resident microglia and is subsequently targetable.76 There are currently no ongoing clinical trials with this target.

EPHA2

EPHA2 is a glioma TAA that is overexpressed in multiple tumor types and drives tumorigenesis.78 Preclinical studies demonstrated the ability of EPHA2-directed CAR-T cells to eliminate GBM tumor cells in vitro and in vivo.79,80 EPHA2-directed CAR-T cells are currently undergoing clinical testing, with a preliminary report of 3 lymphodepleted cases receiving intravenous CAR-T cells (NCT03423992) published recently showing partial objective response in 1 patient, disease progression in all patients, CAR-T persistence of at least 28 days in all patients, and pulmonary edema requiring corticosteroids in 2 patients. OS ranged from 86 to 181 days.81 Another trial was listed and then withdrawn before recruiting any patients (NCT02575261).

Chlorotoxin

Work by several groups demonstrates that the tumor-binding domain of CAR technology can be extended beyond monoclonal antibody-derived scFvs. Wang and colleagues are exploiting the ability of chlorotoxin (CLTX), a peptide found in death stalker scorpion (Leiurus quinquestriatus) venom, to bind to GBM cells broadly and preferentially over normal cells. While CLTX is not cytotoxic, using it as the CAR’s tumor-binding domain generated robust anti-tumor activity against patient-derived tumor cells in vitro and in vivo with no detected cytotoxicity. Interestingly, they showed this activity is dependent on matrix metallopeptidase 2 expression. While the authors did not show direct evidence of GSC-specific elimination, they provide evidence of strong CLTX binding to GSCs.82 A Phase 1 dose-escalation study of their CLTX-CAR for recurrent or progressive GBM is currently underway (NCT04214392).

DC Vaccines

DCs are professional APCs that uptake, process and present antigens to CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells, leading to activation and differentiation into effector cells, and producing a polyclonal anti-tumor response (Figure 1). They can be generated ex vivo by differentiating either circulating monocytes or CD34+ HSCs. Intradermal, intratumor, and intranodal delivery of activated DCs pulsed ex vivo with TAAs, either as mRNA, synthetic peptides, tumor-derived peptides, or tumor lysate, have been extensively tested in multiple human malignancies including GBM (Tables 1 and 2).

Clinical Studies with DCs in GBM

There have been at least 60 clinical trials with DCs in GBM, with 22 trials completed. Out of 6 total Phase 3 trials, the only completed Phase 3 trial (NCT00045968) used autologous tumor lysate-pulsed DC vaccines with standard-of-care (SOC) versus SOC with placebo, with the patient’s decision to crossover to DCV upon disease progression.83 With significant control arm attrition due to crossover, the study was only able to derive placebo-controlled conclusions about progression-free survival (PFS) , but not OS, and it failed this primary endpoint. A post-hoc analysis with contemporaneous external controls was used to infer OS benefit; however, concerns were raised over the scientific rigor of the external controls, the appropriateness of the cross-over design for evaluating OS, and the interpretation of inadequately controlled outcome data.84 In light of this, the other two active Phase 3 trials (NCT05100641, NCT03548571) should be used to confirm these data.

Due to the extensive clinical testing, the safety profile of DC vaccines is well-characterized. However, as with other cellular therapies, the majority of trials have been uncontrolled, thereby limiting reliable conclusions. Gary Archer’s group has notably conducted multiple multi-armed trials, allowing optimization of their CMV pp65-directed DC vaccine protocol parameters such as pre-conditioning approach. Across DC vaccine platforms, vaccine design questions such as the ideal loading strategy are yet to be elucidated. Autologous tumor lysate-pulsed constrain patient selection to those with resectable lesions while synthetic TAA peptides pool-pulsed products are limited by HLA restriction. Results for 4 peptide-pulsed DC vaccine clinical trials have been reported thus far, showing mixed benefits. Strikingly, Phuphanich’s group used a pool of HER2, TRP2, gp100, MAGE1, IL13RA2, and AIM2 peptides—chosen to specifically target GSCs, which led to some patients exhibiting exceptional survival, with 7 of 16 still alive and without progression at ≥4 year.85 However, patients were selected based on antigen mRNA expression, rather than protein expression levels. It is challenging to identify TAAs that maximize therapeutic efficacy considering the heterogeneity, plasticity, and low immunogenicity of GBM tumors. It is also important to consider that DC vaccines, including tumor lysate-pulsed approaches, a priori may be expected to lose efficacy over time as antigen-negative subclones are selected, thereby suggesting TAA-adaptable trial designs could reveal therapeutic insights.

Furthermore, DCs generated ex vivo show limited migration with some results showing on average fewer than 5% of DCs successfully migrating to draining lymph nodes (LNs) post-delivery.86 Different groups tried to maximize DC migration, at times specifically to cervical LNs, using strategies like injection site immune pre-conditioning, intradermal delivery near cervical LNs, or cervical intranodal delivery (NCT02366728, NCT01171469, NCT01213407). Currently, there is no published data to establish superiority of a LN migration threshold or administration approach. Mitchell et al. showed that the adjuvant tetanus/diphtheria toxoid (Td) is associated with improved migration to LNs in a randomized controlled trial (NCT02366728) with survival data not yet published, although a small subset of a different trial demonstrated association with improved PFS and OS (NCT00639639).87

Despite the aforementioned challenges, a recent meta-analysis of clinical trials of DC vaccines in GBM concluded that while this approach did not improve 6-month PFS or OS, it is associated with a significant improvement in 1-year and 2-year OS.88 While these data are encouraging, well-designed clinical trials with the necessary controls will remain the best determinant of DC vaccine efficacy, and vaccine and protocol design optimization.

Addressing Heterogeneity with Cell-based Therapy

The heterogeneity of GBM is multifaceted, spanning spatiotemporal, molecular, immunological, and microenvironmental aspects, with overlap among these categories. Different cell therapy technologies discussed here harbor different advantages to partially surmount some facets of heterogeneity, but are left vulnerable to others. Across the board, cellular therapies’ ability to traffic to GBM is a major advantage over passive therapies such as cytotoxic chemotherapy, small molecules, and biologics. Concomitant therapies are also particularly important factors affecting protocol design, as SOC cytotoxic chemotherapy and glucocorticoids, used against cerebral edema, are both immunosuppressive, thereby affecting leukocyte-based cellular therapies. Trial results comparison is confounded by the fact some studies exclude patients who recently received these therapies, while others have chemotherapy, as well as radiotherapy, as part of the trial design. On the other hand, stem cells are free from the burden of immune evasion, but require additional engineering or modification to enable tumor-killing capabilities which are prone to molecular heterogeneity. NK cells are antigen-naive but vulnerable to immunosuppression and NK activation/inhibitory signaling heterogeneity. CAR T cells and CAR NK cells overcome major antigen presentation and immunosuppression heterogeneity, demonstrate prolonged persistence, and disregard the need for intact tumor downstream signaling that small molecule targeted therapies rely on; however, narrow antigen scope, limited antigen selection, antigen escape, and other immune evasion mechanisms thwart their efficacy. The multipronged, antigenically diverse immune response generated by DC vaccines contrasts starkly with CAR’s oligospecificity, but immunosuppression, target identification, and successful migration of DCs to tumors all remain a challenge.

These characteristics may be used to guide combination therapies for future clinical trials. For example, cellular therapies that are vulnerable to immunosuppression, such as CAR therapies and DC vaccines, may be paired with immune checkpoint inhibitors (eg, NCT04003649, NCT03726515) or other anti-immunosuppression agents (NCT03688178). Furthermore, monovalent CARs and peptide-pulsed DC vaccines may benefit from expanding the number of targets either through multifunctional CAR (NCT05577091) or in combination with ADCs. In another example, our group recently completed a study demonstrating enhanced migration, activation, and potency of GBM-directed CAR-T cells with the use of NSCs engineered to secrete immune regulatory cytokines (manuscript under review). Importantly, future combination therapy or monotherapy studies, even in early phases, would produce the most value to the field if they have multiple arms to allow inference, or at least hypothesis generation, about outcomes, indications, and protocol parameters, such as timing of therapies relative to one another (NCT04003649), dosing schedules (NCT05577091), different modes of administration (NCT02208362, NCT04214392), or different clinical indications (NCT05660369). Furthermore, the use of PFS as a primary endpoint, while commonplace, may be particularly inappropriate for GBM given the confounding effects of pseudo-progression. As analyzed thoroughly in a systematic review by Belin et al., PFS was validated as a surrogate of OS in only about half of all studies analyzed, and RECIST criteria for progression may not be valid for immunotherapies given the criteria are based on cytotoxic chemotherapy trials.89

Perspective: The Future of GBM Cellular Therapy Clinical Trials

We presented here a summary of cell-based therapies that could alter the devastating outcomes of GBM patients due to their resistance to tumor heterogeneity, modularity, safety profile, tumor tropism, and delivery options. It is imperative that trials be informed by the available clinical data and contemporary understanding of GBM. Therefore, we posit that future trials should be guided by the following inferences drawn from this review: (1) Prioritize combination therapy over monotherapy to overcome heterogeneity, (2) deliver cellular products locoregionally to facilitate trafficking to lesions across the CNS, (3) given the high variability in adoptive transfer protocols and the need for combination therapy, design studies to test multiple protocol parameters to optimize these variables across the neuro-oncology community, (4) prioritize OS as primary endpoint over PFS given the lack of strong validation of PFS as a surrogate endpoint, especially with immunotherapy and in GBM, and the known confounding of pseudo-progression, (5) extensively characterize super-responders to facilitate generation of hypotheses for treatment development, and (6) when possible, bank specimens of cellular therapy sources at diagnosis to expedite potential autologous cell delivery during tumor progression. As cellular therapeutics evolve and trial protocols are optimized, we anticipate that these guidelines will help translate into the survival and quality-of-life benefits GBM patients deserve.

Contributor Information

Dean Nehama, Department of Internal Medicine, Montefiore Medical Center, New York, New York, USA.

Alex S Woodell, Division of Pharmacoengineering and Molecular Pharmaceutics, UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA; Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA.

Spencer M Maingi, Division of Pharmacoengineering and Molecular Pharmaceutics, UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA; Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA.

Shawn D Hingtgen, Division of Pharmacoengineering and Molecular Pharmaceutics, UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA; Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA.

Gianpietro Dotti, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Cancer Institute (R01CA256898, R01CA247436, R01CA243543, R01-CA193140) and American Association for Cancer Research (SU2C-AACR-DT29-19).

Conflict of interest statement G.D. is a member of the scientific advisory board of Bellicum Pharmaceutical and Catamaran.

References

- 1. Ostrom QT, Cioffi G, Gittleman H, et al. CBTRUS statistical report: primary brain and other central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2012-2016. Neuro Oncol. 2019;21:V1–V100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, et al. The 2016 World Health Organization classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131(6):803–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Parsons DW, Jones S, Zhang X, et al. An integrated genomic analysis of human glioblastoma multiforme. Science. 2008;321(5897):1807–1812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Phillips HS, Kharbanda S, Chen R, et al. Molecular subclasses of high-grade glioma predict prognosis, delineate a pattern of disease progression, and resemble stages in neurogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2006;9(3):157–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Verhaak RGW, Hoadley KA, Purdom E, et al. ; Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Integrated genomic analysis identifies clinically relevant subtypes of glioblastoma characterized by abnormalities in PDGFRA, IDH1, EGFR, and NF1. Cancer Cell. 2010;17(1):98–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ohgaki H, Kleihues P.. The definition of primary and secondary glioblastoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(4):764–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brennan CW, Verhaak RGW, McKenna A, et al. The somatic genomic landscape of glioblastoma. Cell. 2013;155(2):462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, et al. ; European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Brain Tumor and Radiotherapy Groups. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(10):987–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stupp R, Wong ET, Kanner AA, et al. NovoTTF-100A versus physician’s choice chemotherapy in recurrent glioblastoma: A randomised phase III trial of a novel treatment modality. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48(14):2192–2202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stupp R, Taillibert S, Kanner A, et al. Effect of tumor-treating fields plus maintenance temozolomide vs maintenance temozolomide alone on survival in patients with glioblastoma a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318(23):2306–2316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Diaz RJ, Ali S, Qadir MG, et al. The role of bevacizumab in the treatment of glioblastoma. J Neurooncol. 2017;133(3):455–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Touat M, Idbaih A, Sanson M, Ligon KL.. Glioblastoma targeted therapy: updated approaches from recent biological insights. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(7):1457–1472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gan HK, Van Den Bent M, Lassman AB, Reardon DA, Scott AM.. Antibody-drug conjugates in glioblastoma therapy: The right drugs to the right cells. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2017;14(11):695–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cloughesy TF, Landolfi J, Vogelbaum MA, et al. Durable complete responses in some recurrent high-grade glioma patients treated with Toca 511 + Toca FC. Neuro Oncol. 2018;20(10):1383–1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Desjardins A, Gromeier M, Herndon JE, et al. Recurrent glioblastoma treated with recombinant poliovirus. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(2):150–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rosenberg SA, Yannelli JR, Yang JC, et al. Treatment of patients with metastatic melanoma with autologous tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and interleukin 2. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994;86(15):1159–1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hong JJ, Rosenberg SA, Dudley ME, et al. Successful treatment of melanoma brain metastases with adoptive cell therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(19):4892–4898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mukherji B, Chakraborty NG, Yamasaki S, et al. Induction of antigen-specific cytolytic T cells in situ in human melanoma by immunization with synthetic peptide-pulsed autologous antigen presenting cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92(17):8078–8082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Porter DL, Levine BL, Kalos M, Bagg A, June CH.. Chimeric antigen receptor–modified T cells in chronic lymphoid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(8):725–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sun Z, Wang S, Zhao RC.. The roles of mesenchymal stem cells in tumor inflammatory microenvironment. J Hematol Oncol. 2014;7(1):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hu J, Zhao Q, Kong LY, et al. Regulation of tumor immune suppression and cancer cell survival by CXCL1/2 elevation in glioblastoma multiforme. Sci Adv. 2021;7(5):eabc2511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liesveld JL, Sharma N, Aljitawi OS.. Stem cell homing: from physiology to therapeutics. Stem Cells. 2020;38(10):1241–1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Imitola J, Raddassi K, Park KI, et al. Directed migration of neural stem cells to sites of CNS injury by the stromal cell-derived factor 1α/CXC chemokine receptor 4 pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(52):18117–18122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Aboody KS, Brown A, Rainov NG, et al. Neural stem cells display extensive tropism for pathology in adult brain: Evidence from intracranial gliomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(23):12846–12851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Park, SA, Ryu CH, Kim SM, et al. CXCR4-transfected human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells exhibit enhanced migratory capacity towards gliomas. Int J Oncol. 2011;38:97–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Koizumi S, Gu C, Amano S, et al. Migration of mouse-induced pluripotent stem cells to glioma-conditioned medium is mediated by tumor-associated specific growth factors. Oncol Lett. 2011;2(2):283–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nakamura K, Ito Y, Kawano Y, et al. Antitumor effect of genetically engineered mesenchymal stem cells in a rat glioma model. Gene Ther. 2004;11(14):1155–1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dührsen L, Hartfuß S, Hirsch D, et al. Preclinical analysis of human mesenchymal stem cells: Tumor tropism and therapeutic efficiency of local HSV-TK suicide gene therapy in glioblastoma. Oncotarget. 2019;10(58):6049–6061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Halleka M, Wanders L, Strohmeyer S, et al. Thymidine kinase: a tumor marker with prognostic value for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and a broad range of potential clinical applications. Ann Hematol. 1992;65(1):1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Huang WC, Lu IL, Chiang WH, et al. Tumortropic adipose-derived stem cells carrying smart nanotherapeutics for targeted delivery and dual-modality therapy of orthotopic glioblastoma. J Control Release. 2017;254:119–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bryukhovetskiy IS, Dyuizen IV, Shevchenko VE, et al. Hematopoietic stem cells as a tool for the treatment of glioblastoma multiforme. Mol Med Rep. 2016;14(5):4511–4520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Noyan F, Díez IA, Hapke M, Klein C, Dewey RA.. Induced transgene expression for the treatment of solid tumors by hematopoietic stem cell-based gene therapy. Cancer Gene Ther. 2012;19(5):352–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Flores C, Pham C, Snyder D, et al. Novel role of hematopoietic stem cells in immunologic rejection of malignant gliomas. Oncoimmunology. 2015;4(3):e994374e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Karen SA, Joseph N, Marianne ZM, et al. Neural stem cell-mediated enzyme-prodrug therapy for glioma: preclinical studies. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5(184):184ra59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pituch KC, Zannikou M, Ilut L, et al. Neural stem cells secreting bispecific T cell engager to induce selective antiglioma activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2021;118(9):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mooney R, Weng Y, Tirughana-Sambandan R, et al. Neural stem cells improve intracranial nanoparticle retention and tumor-selective distribution. Future Oncol. 2014;10(3):401–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gao M, Yao H, Dong Q, et al. Tumourigenicity and immunogenicity of induced neural stem cell grafts versus induced pluripotent stem cell grafts in syngeneic mouse brain. Sci Rep. 2016;6(July):1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Berglund AK, Fortier LA, Antczak DF, Schnabel LV.. Immunoprivileged no more: Measuring the immunogenicity of allogeneic adult mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2017;8(1):1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bagó JR, Alfonso-Pecchio A, Okolie O, et al. Therapeutically engineered induced neural stem cells are tumour-homing and inhibit progression of glioblastoma. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bagó JR, Okolie O, Dumitru R, et al. Tumor-homing cytotoxic human induced neural stem cells for cancer therapy. Sci Transl Med. 2017;9(375):eaah6510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Birocchi F, Cusimano M, Rossari F, et al. Targeted inducible delivery of immunoactivating cytokines reprograms glioblastoma microenvironment and inhibits growth in mouse models. Sci Transl Med. 2022;14(653):eabl4106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Portnow J, Badie B, Suzette Blanchard M, et al. Feasibility of intracerebrally administering multiple doses of genetically modified neural stem cells to locally produce chemotherapy in glioma patients. Cancer Gene Ther. 2021;28(3-4):294–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Fares J, Ahmed AU, Ulasov IV, et al. Neural stem cell delivery of an oncolytic adenovirus in newly diagnosed malignant glioma: a first-in-human, phase 1, dose-escalation trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(8):1103–1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ulasov IV, Zhu ZB, Tyler MA, et al. Survivin-driven and fiber-modified oncolytic adenovirus exhibits potent antitumor activity in established intracranial glioma. Hum Gene Ther. 2007;18(7):589–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Chester C, Fritsch K, Kohrt HE.. Natural killer cell immunomodulation: Targeting activating, inhibitory, and co-stimulatory receptor signaling for cancer immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2015;6(DEC):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Caligiuri MA. Human natural killer cells. Blood. 2008;112(3):461–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ruggeri L, Capanni M, Urbani E, et al. Effectiveness of donor natural killer cell aloreactivity in mismatched hematopoietic transplants. Science. 2002;295(5562):2097–2100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Passweg JR, Tichelli A, Meyer-Monard S, et al. Purified donor NK-lymphocyte infusion to consolidate engraftment after haploidentical stem cell transplantation. Leukemia. 2004;18(11):1835–1838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Locatelli F, Moretta F, Brescia L, Merli P.. Natural killer cells in the treatment of high-risk acute leukaemia. Semin Immunol. 2014;26(2):173–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zeng J, Tang SY, Toh LL, Wang S.. Generation of “Off-the-Shelf” natural killer cells from peripheral blood cell-derived induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell Rep. 2017;9(6):1796–1812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Shaim H, Shanley M, Basar R, et al. Targeting the αv integrin-TGF-β axis improves natural killer cell function against glioblastoma stem cells. J Clin Invest. 2021;131(14):e142116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Tanaka Y, Nakazawa T, Nakamura M, et al. Ex vivo-expanded highly purified natural killer cells in combination with temozolomide induce antitumor effects in human glioblastoma cells in vitro. PLoS One. 2019;14(3):e02124551–e02124514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Navarro AG, Espedal H, Joseph JV, et al. Pretreatment of glioblastoma with bortezomib potentiates natural killer cell cytotoxicity through TRAIL/DR5 mediated apoptosis and prolongs animal survival. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11(7):1–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Zhang C, Hu Y, Shi C.. Targeting natural killer cells for tumor immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2020;11(February):60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kmiecik J, Zimmer J, Chekenya M.. Natural killer cells in intracranial neoplasms: Presence and therapeutic efficacy against brain tumours. J Neurooncol. 2014;116(1):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Grizzi F, Mirandola L, Qehajaj D, et al. Cancer-testis antigens and immunotherapy in the light of cancer complexity. Int Rev Immunol. 2015;34(2):143–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Maggs L, Cattaneo G, Dal AE, Moghaddam AS, Ferrone S.. CAR T cell-based immunotherapy for the treatment of glioblastoma. Front Neurosci. 2021;15(May):662064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Klichinsky M, Ruella M, Shestova O, et al. Human chimeric antigen receptor macrophages for cancer immunotherapy. Nat Biotechnol. 2020;38(8):947–953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Brown CE, Badie B, Barish ME, et al. Bioactivity and safety of IL13R α2-redirected chimeric antigen receptor CD8+ T cells in patients with recurrent glioblastoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(18):4062–4072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Brown CE, Alizadeh D, Starr R, et al. Regression of glioblastoma after chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(26):2561–2569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Wang D, Aguilar B, Starr R, et al. Glioblastoma-targeted CD4+ CAR T cells mediate superior antitumor activity. JCI insight. 2018;3(10):1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Sahin A, Sanchez C, Bullain S, et al. Development of third generation anti-EGFRvIII chimeric T cells and EGFRvIII-expressing artificial antigen presenting cells for adoptive cell therapy for glioma. PLoS One. 2018;13(7):e01994141–e01994119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. O’Rourke DM, Nasrallah MP, Desai A, et al. A single dose of peripherally infused EGFRvIII-directed CAR T cells mediates antigen loss and induces adaptive resistance in patients with recurrent glioblastoma. Sci Transl Med. 2017;9(399):eaaa0984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Goff SL, Morgan RA, Yang JC, et al. Pilot trial of adoptive transfer of chimeric antigen receptor transduced T cells targeting EGFRvIII in patients with glioblastoma. J Immunother. 2019;42(4):126–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Weller M, Butowski N, Tran DD, et al. ; ACT IV trial investigators. Rindopepimut with temozolomide for patients with newly diagnosed, EGFRvIII-expressing glioblastoma (ACT IV): a randomised, double-blind, international phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(10):1373–1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Zhang JG, Kruse CA, Driggers L, et al. Tumor antigen precursor protein profiles of adult and pediatric brain tumors identify potential targets for immunotherapy. J Neurooncol. 2008;88(1):65–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Ahmed N, Salsman VS, Kew Y, et al. HER2-specific T cells target primary glioblastoma stem cells and induce regression of autologous experimental tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(2):474–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Ahmed N, Brawley V, Hegde M, et al. HER2-specific chimeric antigen receptor–modified virus-specific T cells for progressive glioblastoma: a phase 1 dose-escalation trial. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(8):1094–1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Burger MC, Zhang C, Harter PN, et al. CAR-engineered NK cells for the treatment of glioblastoma: turning innate effectors into precision tools for cancer immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2019;10(November):1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Nehama D, Di Ianni N, Musio S, et al. B7-H3-redirected chimeric antigen receptor T cells target glioblastoma and neurospheres. EBioMedicine. 2019;47:33–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Du H, Hirabayashi K, Ahn S, et al. Antitumor responses in the absence of toxicity in solid tumors by targeting B7-H3 via chimeric antigen receptor T cells. Cancer Cell. 2019;35(2):221–237.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Seaman S, Zhu Z, Saha S, et al. Eradication of tumors through simultaneous ablation of CD276/B7-H3-positive tumor cells and tumor vasculature. Cancer Cell. 2017;31(4):501–515.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Tang X, Zhao S, Zhang Y, et al. B7-H3 as a novel CAR-T therapeutic target for glioblastoma. Mol Ther Oncolytics. 2019;14(37):279–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Rolih V, Barutello G, Iussich S, et al. CSPG4: a prototype oncoantigen for translational immunotherapy studies. J Transl Med. 2017;15(1):1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Geldres C, Savoldo B, Hoyos V, et al. T lymphocytes redirected against the chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan-4 control the growth of multiple solid tumors both in vitro and in vivo. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(4):962–971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Pellegatta S, Savoldo B, Di Ianni N, et al. Constitutive and TNFα-inducible expression of chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan 4 in glioblastoma and neurospheres: Implications for CAR-T cell therapy. Sci Transl Med. 2018;10(430):1–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Beard RE, Zheng Z, Lagisetty KH, et al. Multiple chimeric antigen receptors successfully target chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan 4 in several different cancer histologies and cancer stem cells. J ImmunoTher Cancer. 2014;2(1):251–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Ieguchi K, Maru Y.. Roles of EphA1/A2 and ephrin-A1 in cancer. Cancer Sci. 2019;110(3):841–848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Yi Z, Prinzing BL, Cao F, Gottschalk S, Krenciute G.. Optimizing EphA2-CAR T cells for the adoptive immunotherapy of glioma. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2018;9(June):70–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Chow KK, Naik S, Kakarla S, et al. T cells redirected to EphA2 for the immunotherapy of glioblastoma. Mol Ther. 2013;21(3):629–637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Lin Q, Ba T, Ho J, et al. First-in-human trial of EphA2-redirected CAR T-cells in patients with recurrent glioblastoma: a preliminary report of three cases at the starting dose. Front Oncol. 2021;11(June):1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Wang D, Starr R, Chang WC, et al. Chlorotoxin-directed CAR T cells for specific and effective targeting of glioblastoma. Sci Transl Med. 2020;12(533):aaw2672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Liau LM, Ashkan K, Brem S, et al. Association of autologous tumor lysate-loaded dendritic cell vaccination with extension of survival among patients with newly diagnosed and recurrent glioblastoma. JAMA Oncol. 2023;9(1):112–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Preusser M, van den Bent MJ.. Autologous tumor lysate-loaded dendritic cell vaccination (DCVax-L) in glioblastoma: breakthrough or fata morgana? Neuro Oncol. 2023;25(4):631–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Phuphanich S, Wheeler CJ, Rudnick JD, et al. Phase i trial of a multi-epitope-pulsed dendritic cell vaccine for patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2013;62(1):125–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. De Vries IJM, Krooshoop DJEB, Scharenborg NM, et al. Effective migration of antigen-pulsed dendritic cells to lymph nodes in melanoma patients is determined by their maturation state. Cancer Res. 2003;63(1):12–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Mitchell DA, Batich KA, Gunn MD, et al. Tetanus toxoid and CCL3 improve dendritic cell vaccines in mice and glioblastoma patients. Nature. 2015;519(7543):366–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Cozzi S, Najafi M, Gomar M, et al. Delayed effect of dendritic cells vaccination on survival in glioblastoma: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Curr Oncol. 2022;29(2):881–891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Belin L, Tan A, De Rycke Y, Dechartres A.. Progression-free survival as a surrogate for overall survival in oncology trials: a methodological systematic review. Br J Cancer. 2020;122(11):1707–1714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]