Abstract

Fungal infections are now becoming a hazard to individuals which has paved the way for research to expand the therapeutic options available. Recent advances in drug design and compound screening have also increased the pace of the development of antifungal drugs. Although several novel potential molecules are reported, those discoveries have yet to be translated from bench to bedside. Polyenes, azoles, echinocandins, and flucytosine are among the few antifungal agents that are available for the treatment of fungal infections, but such conventional therapies show certain limitations like toxicity, drug interactions, and the development of resistance which limits the utility of existing antifungals, contributing to significant mortality and morbidity. This review article focuses on the existing therapies, the challenges associated with them, and the development of new therapies, including the ongoing and recent clinical trials, for the treatment of fungal infections.

Graphical Abstract

Advancements in antifungal treatment: a graphical overview of drug development, adverse effects, and future prospects.

Keywords: Anti-fungals, Clinical trials, Drug development, Fungicides, Pharmacology

Introduction

Fungal infections affect approximately 1.7 billion people globally [1, 2]. Pathologically significant fungal infections can be divided into two categories: Invasive fungal infections and superficial fungal infections [3]. Thrush, oropharyngeal candidiasis, and dermatophyte infections are examples of superficial infections that affect the skin, mucous membranes, and keratinous tissues. Dermatophytes (such as Trichophyton, Microsporum, and Epidermophyton), as well as other fungi such as Malassezia spp., Candida spp., and dimorphic fungi like Sporothrix schenckii, can cause superficial fungal infections, especially in skin, nails, and hair [4]. Such superficial infections caused by fungi affect 25% of the world population, one of the major diseases being skin mycoses [5]. Conventional treatment is usually effective for such infections, but some ailments like onychomycosis have shown a very high failure rate of 25%, and recurrence is frequently reported [6]. Resistance to conventional therapies is now on an increase as seen recently in India for dermatophytoses resistant to terbinafine [7]. Conventional drugs have also caused several adverse events like liver toxicity and unwanted drug interactions [8].

Invasive fungal infections are more dangerous since they attack sterile body parts such as the bloodstream, organs (lungs, liver, and kidneys), and the central nervous system [1]. To date, there are about 5 million known species of fungus out of which 20 species are known to frequently infect human beings[9], and these species include Histoplasma capsulatum, Sporothrix spp., Candida albicans, Scedosporium, Coccidiodes immitis, Fusarium, Aspergillus fumigatus, Blastomyces dermatitidis, Candida auris, Malassezia furfur, and Cryptococcus neoformans [9, 10]. As per the findings of RCTs (Randomized Clinical Trials), the first line of treatment against Candida spp. involves the administration of echinocandins, while for Aspergillus spp., azole anti-mycotic drugs are employed [11].

Antifungal resistance is a growing concern in both clinical and agricultural settings [12, 13]. While the development of new antifungal drugs has been a crucial focus in recent years, the impact of intense antifungal use in agriculture cannot be ignored. Fungi that cause plant diseases are often treated with the same antifungal drugs used in human medicine[14]. One such example is the use of azoles, to treat fungal infections in plants such as wheat, barley, and corn [15]. Extensive use of azoles in agriculture has led to the emergence of azole-resistant strains of plant pathogenic fungi. These resistant strains can spread to other plants, and in some cases, even to humans who consume the crops[16]. Recent years have shown acquired resistance against echinocandins [17] as well as azole-resistant strains in major parts of Europe [18]. Such unregulated use of anti-fungal drugs poses a threat to public health. Widespread anti-fungal resistance has posed greater challenges to researchers and pharmaceutical companies to develop newer and more efficient alternatives. Moreover, the heterogeneity of the patients who are at risk for such invasive infections has reached a new high, such as patients who have undergone stem cell transfer or patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or severe influenza [19, 20]. Therefore, the selection of the exact type of therapy to be given to such patients has become more complex. Thus, there is a pressing need to employ novel drugs which do not show any kind of resistance.

An alarming increase in the number of reported fungal infections has been caused by an increase in the number of at-risk patients and improved detection procedures [21, 22]. In the past, there was a very limited development of antifungal medications. There are mainly 4 existing classes of antifungal drugs namely: Polyenes, Azoles, Echinocandins, and flucytosine [23]. These existing classes of drugs exhibit certain disadvantages like drug resistance, variations in pharmacokinetics, toxicity, decreased bioavailability, and drug-drug interactions [24]. Antifungal medication development is difficult because fungi share a lot of eukaryotic mechanisms with humans, thus limiting the number of pathogen-specific targets. Therefore, in order to synthesize the next generation(s) of antifungal therapies, it is critical to uncover biochemical pathways unique to fungi as drug development targets. Various novel therapies with distinct mechanisms of action and the drugs that are undergoing clinical trials have been discussed in this review.

Existing anti-fungal drugs

The current anti-fungal drugs are classified into the following categories:

Antibiotics

They are further classified into:

Polyenes

Polyenes are the oldest family of antifungal drugs which were introduced as early as in 1950s [25]. Many polyenes have been isolated from Streptomyces spp., but only Amphotericin B (AmpB) remains in widespread use, especially with the advent of its many formulations like liposomal AmpB [26], topical nystatin [27], and AmpB lipid complex [28]. It has been known that polyenes, including Amp B which is a bigger polyene, interact with the membrane sterols, mostly ergosterol, which leads to the formation of aqueous pores. In the case of AmpB, the pore contains an annulus of 8 molecules of AmpB which is hydrophobically attached to the membrane sterols [29, 30]. This structure causes the formation of a pore in which the polyene hydroxyl is placed inward and leads to leakage of essential components of cytoplasm, modified permeation of substances, and thus leads to the death of the fungal cell [31]. Polyenes have shown a wide range of activity. They have exhibited efficiency against Candida spp., Fusarium spp., Aspergillus spp., as well as Mucorales. But at the same time, polyenes have been able to show only limited activity against Scedosporium spp [32].

-

b)

Echinocandins

Echinocandins are comparatively the newest antifungal class and majorly include caspofungin, anidulafungin, and micafungin. The fungal cell membrane consists of a heteromeric glycosyltransferase enzyme complex known as Beta-(1,3)-D-glucan synthase, which is primarily made of catalytic Fks p subunit and a regulatory subunit belonging to the family of Rho GTPase[33]. The regulatory and catalytic subunits are linked to the UDP-glucose and GTP, intracellularly. Echinocandins exhibit their fungicidal activity against the pathogens through non-competitive binding to the Fks p subunit of the enzyme and blocking the beta-(1,3)-D-glucan synthesis, which ultimately leads to a highly permeable and leaky cell wall and causes an imbalance in the osmotic pressure intracellularly, thus, resulting in cell lysis of the fungal cell [33]. Echinocandins show their fungicidal action against Candida ssp. and Aspergillus ssp. But they are not active against Scedosporium spp., Fusarium spp., and Cryptococcus spp. and are thus not recommended for the treatment of infections caused by these species [34].

-

iii)

Heterocyclic benzofuran

Griseofulvin which is a heterocyclic Benzofuran is an inhibitor of microtubule assembly [35]. It combines with microtubules to modify the synthesis of the mitotic spindle, which leads to the inhibition of mitosis in the fungal cells. By demonstrating this action, Griseofulvin acts as a fungistatic substance against various species of fungi like Epidermophyton, Microsporum, and Trichophyton [36]. But, it is not effective for the treatment of chromomycosis, dimorphic fungi, and yeast (Malassezia, Candida). Griseofulvin has a less half-life and is easily eliminated from the body; therefore, it should be administered over an extended period of time for better effectiveness [36].

Antimetabolites

5-Fluorocytosine (5FC) is the only available antimetabolite [37]. It is a fluorinated pyrimidine that exhibits anti-fungal actions against various fungal species like yeasts (Candida and Cryptococcus neoformans). The permease enzyme enables the 5FC to permeate into the fungi. As a result, the enzyme cytosine deaminase converts 5FC into 5-fluorouracil (5FU), which is then converted into 5-fluorouridylic acid (FUMP) by UMP pyrophosphorylase, and then FUMP is further phosphorylated and then inserted into the fungal RNA, thus, causing interference for the synthesis of proteins [38]. 5FU is also transformed into 5-fluorodeoxyuridine monophosphate, which causes inhibition of thymidylate synthase that plays a major role in nuclear division and synthesis of DNA [39]. Therefore, 5-fluorocytosine not only inhibits the metabolism of pyrimidine but also interferes with the synthesis of DNA, RNA, and proteins in the fungal pathogen [37]. 5-Fluorocytosine has exhibited secondary resistance which has prompted combining fluconazole or AmpB for administering the same to patients [40].

Azoles

The activity of azoles is similar to that of polyenes as they also target the fungal cell membrane. Ergosterol, which is an essential component of the fungal cell membrane, maintains its fluidity and asymmetry and thus provides integrity in the cells of fungi [41]. The lack of C-4 methyl groups in the sterols is essential for maintaining the integrity of the fungal cell membranes. Azoles mainly target the heme protein which co-catalyzes cytochrome P-450-dependent 14a-demethylation of lanosterol [42]. The degradation of the 14a-demethylase leads to the destruction of ergosterol and accumulation of the precursors of the sterol which also includes 14a-methylated sterols (24-methylenedihydrolanosterol and lanosterol, 4,14 dimethyl zymosterol), therefore, causing modifications in the structure and functions of the cell membrane. Azoles have exhibited fungicidal activity against Aspergillus spp., whereas they show fungistatic activity against Candida spp. Azoles have been effective against Cryptococcus spp.; however, they have shown mixed and limited activity against Mucorales, Scedosporium spp., and Fusarium spp [43].

Allylamines

Allylamines are a comparatively newer class of antifungals that include naftifine and terbinafine. Terbinafine is both orally and topically effective against dermatophytes (Epidermophyton spp., Microsporum, Trichophyton) and Candida. Allylamines exhibit antifungal activities by interfering with the biosynthesis of ergosterol, which also leads to the accumulation of the sterol precursor-like squalene and the absence of other intermediates of sterol; therefore, allylamines cause inhibition of synthesis of sterol during squalene epoxidation (a reaction step that catalyzes the squalene epoxidase) [44]. The death of the fungal cells is mainly associated with the accumulation of squalene than the deficiency of ergosterol. The increased amount of squalene in the fungal cells can lead to more permeation across the cell membranes [45], therefore causing interference with the cellular organization.

Terbinafine, when applied topically, causes adverse events like gastrointestinal disturbance, erythema, urticaria, rashes, neutropenia, and musculoskeletal reactions [46]. Similarly, Naftifine has known to cause mild rash, erythema, and moderate burning when applied topically in the application area [47].

Challenges of the current anti-fungal drugs

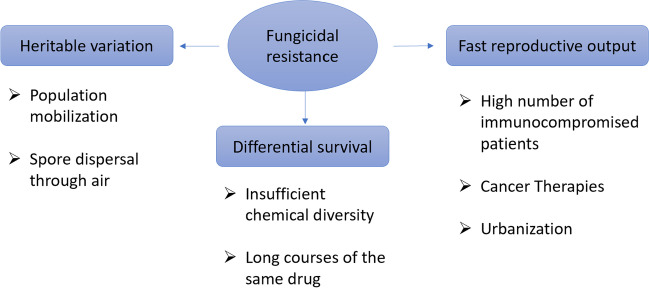

One of the major challenges of anti-fungal drug development is that of fungicide resistance. It has been reported that the rate of development of such resistance is higher than the rate of anti-fungal discovery. Fungi are known to quickly generate variants as they reproduce rapidly and because they have plastic genomes[48]. There are three major evolutionary reasons for fungicidal resistance, namely, differential survival, heritable variation, and fast reproductive output as represented briefly in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Understanding the drivers of fungal adaptation to antifungal therapy

The development of antifungal drugs is undermined by the fact that fungal diseases are more closely linked to their hosts. Many key biochemical and cell biology processes are similar to fungus to humans, which explains Saccharomyces cerevisiae’s usefulness as a model eukaryotic organism [49]. As a result, many tiny compounds poisonous to yeast are toxic to humans as well. As a result, it is not astonishing that the three primary groups of antifungal medications target fungi-specific structures. In parallel to the scientific barriers that influence the recognition of novel lead compounds, the assessment of new antifungal medications has a variety of clinical trial design challenges that further hinder the advancement of novel drugs [50]. These fundamental problems, however, are in addition to the well-documented scientific, regulatory, and economic challenges that plague anti-infective development [51].

In and of itself, the limited number of antifungal medications available would not be a concern if the therapeutic results for invasive fungal infections were effective. Nevertheless, in most cases, for example, 90-day survivability after the detection of candidemia ranges from 55 to 70%, based on the patient’s general condition and the exact species that caused the infection [52]. It is worth noting that distinguishing infection-related mortality from comorbidity-related mortality is one of the most difficult aspects of examining the effects of fungal infections. Despite the usage of voriconazole, the outcomes for neutropenic cancer patients and hemato-oncologic patients are significantly worse. [53, 54].

The spectrum of activity of antifungal drugs varies, and their in vitro sensitivities are frequently examined to determine the resistance patterns of the fungal strain. Drug susceptibility screening of yeasts and filamentous fungi has lately created significant progress. The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) and the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing Subcommittee on Antifungal Susceptibility Testing (EUCASTAFST) have both developed and standardized phenotypic techniques for evaluating the minimum inhibition concentration (MIC) for yeasts and conidia-forming molds. Antifungal drug resistance is typically measured using MIC values, and it has been demonstrated that when MIC values increase, treatment success rates decrease [55–57]. Primary and secondary mechanisms of antifungal drug resistance are linked to innate or evolved properties of the fungal pathogen that disrupts the antifungal action of the corresponding drug/drug class or lower target drug levels [58]. Moreover, resistance can develop when environmental circumstances cause a susceptible species to colonize or be replaced by a resistant species [59]. When a significant number of microbes are exposed to a fungistatic agent for a longer duration, acquired resistance begins to develop. Because of the rising incidence of azole-resistant strains in the surroundings, this condition is especially significant for A. fumigatus infections [59].

Antifungal drugs often have inconvenient posology [60]. Some antifungal drugs require vigilant dosing adjustments based on factors such as renal function and drug interactions. For instance, fluconazole may require a loading dose and maintenance dose due to its long half-life [61], terbinafine requires a long treatment duration and monitoring of liver function [62], and griseofulvin requires a high-fat meal for optimal absorption and can interact with other medications [63]. Similarly, the route of administration of antifungals also poses a great challenge and limits their use in certain patient populations. For example, some antifungal drugs are only available in intravenous (IV) formulations, which require hospitalization or daycare services for administration. This can be challenging for patients who cannot easily access these services, such as those living in remote areas or those with limited mobility. Furthermore, some drugs have only oral formulations available, which may limit their use in critically ill patients who cannot take medications orally [64].

Furthermore, it is worth mentioning that echinocandins, the latest class of antifungal medications, were developed in the 1970s and took 30 years to make their way into clinical practice[59]. The number of individuals at risk for fungal infections is also about to rise as medical innovation and the usage of immunomodulatory medications continue to rise. As a result, the present rate of antifungal drug discovery is unlikely to keep up with the healthcare needs, especially when resistance to existing treatments is becoming more common. Table 1 shows the existing anti-fungal drugs and their associated adverse events which call for more research and development in the field of antifungal drug discovery.

Table 1.

An overview of the existing antifungal medications, including information on their mode of action, spectrum of activity, and associated adverse events

| Class of drugs | Mechanism of action | Existing anti-fungal drugs | Spectrum of activity | Adverse events | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polyenes | Binds to ergosterol in the fungal cell membrane, causing leakage of intracellular contents | Amphotericin B | Broad spectrum: Candida species (including C. albicans, C. parapsilosis, and C. tropicalis, C. krusei, C. kefyr, C. famata, C. guilliermondii), Aspergillus species (including A. fumigatus, A. flavus, A. terreus, A. niger), Cryptococcus neoformans, Histoplasma capsulatum, Blastomyces dermatitidis, Coccidioides immitis, Paracoccidioides brasiliensis, Paecilomyces sp., Penicillium sp., Fusarium sp., Bipolaris sp., Exophiala sp., Cladophialophora sp., Absidia sp., Apophysomyces sp., Mucor sp., Rhizomucor sp., Saksenaea sp. Talaromyces marneffei | Infusion-related toxicity, hypertension/hypotension, hypoxia, hyperkalemia, cardiac toxicity nephrotoxicity, anemia | Walsh et al., [65]; Hoeprich PD., [66]; Anderson CM., [67] |

| Nystatin | Broad spectrum: Candida species (including C. albicans, C. glabrata, and C. tropicalis), Aspergillus species, Cryptococcus neoformans | Gastrointestinal adverse reactions, including vomiting, nausea, diarrhea, anorexia, and abdominal pain | Hoppe JE., [68]; Flynn PM., [69]; Pons V et al., [70]; Blomgren J et al., [71] | ||

| Echinocandins | Inhibit the synthesis of β-(1,3)-D-glucan, a key component of fungal cell wall | Caspofungin | Candida species (including C. albicans, C. glabrata, and C. tropicalis), Aspergillus species (including A. fumigatus and A. flavus), Histoplasma capsulatum, Blastomyces dermatitidis | Phlebitis/thrombophlebitis, tachycardia, hepatitis, hepatomegaly, hyperbilirubinemia | Keating and Figgit., [72]; Fotsing, L.N.D. and Bajaj, T., [73] |

| Micafungin | Broad spectrum: Candida species (including Candida albicans, Candida tropicalis, and Candida parapsilosis), Aspergillus species (including Aspergillus fumigatus), and some dimorphic fungi (such as Histoplasma capsulatum) | Neutropenia, nausea, diarrhea, hyperbilirubinemia, hypokalemia | Eschenauer et al., [74] | ||

| Anidulafungin | Broad spectrum: Candida species (including C. albicans, C. tropicalis, and C. parapsilosis), and Aspergillus species (including Aspergillus fumigatus) | Neutropenia, leukopenia, nausea, dyspepsia, hypokalemia, rash, pyrexia | Eschenauer et al., [74] | ||

| Heterocyclic benzofuran | It is taken up by fungal cells and converted into 5fluorouracil, followed by conversion to 5fluorodeoxyuridylic acid, an inhibitor of thymidylate synthesis | Griseofulvin | Narrow spectrum: dermatophytes (including Trichophyton species, Microsporum species, and Epidermophyton floccosum) | Gastrointestinal adverse reactions, photosensitivity, fixed drug eruption, petechiae, pruritus, and urticaria, elevated triglycerides, anemia | Gupta et al., [75]; Kreijkamp-Kaspers et al., [76]; Chaudhary et al., [77] |

| Antimetabolite | Interferes with fungal nucleic acid synthesis | Flucytosine | Narrow spectrum: Candida species (including C. albicans, C. glabrata, C. tropicalis, and C. parapsilosis), and Cryptococcus neoformans | Gastrointestinal adverse effects, rash, pruritus, acute hepatitis nephrotoxicity, myelotoxicity | Folk et al., [78] |

| Azoles (Imidazoles) | Inhibits the activity of the fungal enzyme cytochrome P450-dependent 14-alpha-sterol demethylase (CYP51), which is responsible for converting lanosterol into ergosterol, a key component of the fungal cell membrane. They inhibit a broader range of CYP enzymes, including human CYP enzymes, which can lead to more drug interactions and adverse effects | Clotrimazole | Broad spectrum: Candida species (including C. albicans, C. glabrata, C. tropicalis, C. krusei, C. parapsilosis, C. guilliermondii, and C. lusitaniae), and some dermatophytes (such as Trichophyton mentagrophytes and Trichophyton rubrum) | Abnormal liver function tests, rash, hives, blisters, burning, itching, peeling, redness, swelling, pain, or other signs of skin irritation | Jelen and Tennstedt., [79] |

| Econazole | Broad spectrum: Candida species (including C. albicans, C. glabrata, C. tropicalis, C. krusei), dermatophytes (including Trichophyton species, Microsporum species, and Epidermophyton floccosum), Malassezia furfur | Irritation, redness, burning, or itching | Heel et al., [80] | ||

| Miconazole | Broad spectrum: Candida species (including C. albicans, C. glabrata, C. tropicalis, C. krusei), dermatophytes (including Trichophyton species, Microsporum species, and Epidermophyton floccosum), Malassezia furfur | Thrombocytopenic purpura, acute gastroenteritis | Yan et al., [81] | ||

| Sulconazale | Broad spectrum: dermatophytes (including Trichophyton species, Microsporum species, and Epidermophyton floccosum), Candida albicans | Redness, irritation, contact dermatitis, and pruritus | Benfield and Stephen., [82] | ||

| Ketoconazole | Broad spectrum: Candida species (including C. albicans, C. glabrata, C. tropicalis, C. krusei), dermatophytes (including Trichophyton species, Microsporum species, and Epidermophyton floccosum), Malassezia furfur | Gastrointestinal side effects, orthostatic hypotension, gynecomastia in males, severe liver injury, and jaundice | Sohn CA., [83]; Gupta and Lyons., [84]; Brass et al., [85] | ||

| Azoles (Triazoles) | Selectively inhibits the fungal CYP51 enzyme, resulting in decreased ergosterol synthesis and accumulation of toxic sterols in the fungal cell membrane | Fluconazole | Broad spectrum: Candida species (including C. albicans, C. glabrata, C. tropicalis, C. krusei, C. parapsilosis), Cryptococcus neoformans, Coccidioides spp. | Gastrointestinal symptoms, anaphylaxis, hepatotoxicity, asthenia, myalgia, Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis, alopecia, and chapped lips | Amichai and Grunwald., [86]; Pappas et al., [87] |

| Itraconazole | Broad spectrum: Candida species (including C. albicans, C. glabrata, C. tropicalis, C. krusei, C. parapsilosis), Aspergillus species (including A. fumigatus, A. flavus, A. niger, A. terreus), Blastomyces dermatitidis, Histoplasma capsulatum, Sporothrix schenckii, Paracoccidioides brasiliensis, Coccidioides spp., Talaromyces marneffei, Histoplasma capsulatum | Cardiotoxicity, gastrointestinal disturbances | Piérard et al., [88]; Abraham and Panda., [89] | ||

| Voriconazole | Broad spectrum: Candida species (including C. albicans, C. glabrata, C. tropicalis, C. krusei, C. parapsilosis), Aspergillus species (including A. fumigatus, A. flavus, A. niger, A. terreus, and A. nidulans), Scedosporium apiospermum, Fusarium species, Histoplasma capsulatum, Coccidioides spp., Talaromyces marneffei | Hepatotoxicity, visual disturbances, and phototoxicity | Re III et al., [90]; Raschi et al., [91]; Saravolatz et al., [92]; Epaulard et al., [93] | ||

| Posaconazole | Broad spectrum: Candida species (including C. albicans, C. glabrata, C. tropicalis, C. krusei, C. parapsilosis), Aspergillus species (including A. fumigatus, A. flavus, A. niger, A. terreus, and A. nidulans), Scedosporium species, Fusarium species, Zygomycetes (including Rhizopus, Mucor, and Absidia species) | Headache, fatigue, QT prolongation, atrial fibrillation, a decreased ejection fraction, and torsades de pointes | Courtney et al., [94]; Cornely et al., [95] | ||

| Allylamine | Inhibits squalene epoxidase, an enzyme involved in the biosynthesis of ergosterol | Terbinafine | Broad spectrum: dermatophytes (including Trichophyton species, Microsporum species, and Epidermophyton floccosum), some dimorphic fungi (including Histoplasma capsulatum and Coccidioides immitis) | Gastrointestinal symptoms, rash, urticaria, erythema, visual disturbances, dysgeusia, and mild transaminitis | Lipner and Scher., [96]; Zane et al., [97] |

| Naftifine | Broad spectrum: dermatophytes (including Trichophyton species, Microsporum species) | Mild and transient burning, itching, and stinging | Gupta et al., [98] |

Novel anti-fungal drugs

In recent decades, there has been minimal progress in the development of novel antifungal drugs [99]. For instance, since Isavuconazole, a third-generation triazole, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2015 (Miceli and Kauffman, [100]) (Fig. 2), only two new drugs have been approved by FDA, namely Oteseconazole (April 2022) [101] and Ibrexafungerp (June 2021) [102]. The genetic and metabolic commonalities between fungal and human cells make it challenging to develop new antifungal medications, making it difficult to uncover specific new fungal targets [99]. As a result, the 3 main classes of antifungal agents that are in use for medical practice have been targeted as structures and metabolic processes that are solely produced by fungi: ergosterol and its biosynthesis pathway, as well as -(1,3)-glucan production. The most common technique used for antifungal medication development is to increase the therapeutic index of presently accessible antifungal drugs by modifying them chemically and developing novel formulations to produce the least toxic compounds [100, 103].

Fig. 2.

An infographic of the antifungal pipeline highlighting the most promising drug candidates and their development timelines

In recent years, various potential antifungal drugs have been patented. Corifungin, a water-soluble sodium salt of AmpB generated by fermentation of Streptomyces nodosus strain NRRLB2371, was patented by ACEA Biotech Inc. (USA) and has wide antifungal functions both in vitro and in vivo [104]. Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) are cationic peptides and are of low molecular weight. They are produced by plants, vertebrates, and invertebrates as part of their innate immune response [105]. C3 Jian (USA) developed a unique set of structures created by several functional domains with action against yeasts and filamentous fungi, by employing a broad spectrum of antibacterial capabilities of AMPs [106]. Similarly, the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation (USA) has patented a number of beta-peptides that contain cyclically restricted -amino acid residues with helical conformations and exhibit significant in vitro action against both planktonic and biofilm-forming C. albicans cells [106].

Polichem SA, Luxembourg (Switzerland), patented chemically synthesized derivatives from 8-hydroxyquinoline-7-carboxamide that exhibited remarkable action against yeasts and filamentous fungus via iron chelation (Stefania et al., 2015). The quinazolinone derivatives patented by F2G Limited (Great Britain), which block the fungal enzyme dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH) and exhibit better effectiveness against Aspergillus spp., are another synthetic drug with a unique mode of action [107]. A sequence of pyrrole derivatives with remarkable in vitro action against filamentous fungus and the ability to improve survivability in murine models of disseminated aspergillosis was also patented by the same company. Janssen Pharmaceutical (Belgium) synthesized and patented synthetic derivatives of pyrrolo[1,2α][1,4]-benzodiazepine substituted with bicyclic benzene rings to combat dermatophytes and species that cause systemic illnesses and, thus, resulting in enhanced bioavailability and metabolic stability [106].

Olorofim is the premier candidate drug of the orotomides, which is a novel class of antifungal agents. Orotomides demonstrate a unique mode of action by causing inhibition of the dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH) [108], which is an important enzyme involved in the biosynthesis of pyrimidine. Pyrimidine is a vital component in the synthesis of DNA, RNA, cell wall, and phospholipids, as well as in cell control and protein synthesis [109]; therefore, the inhibition of the biosynthesis of pyrimidine will significantly affect the fungal pathogen. The DHODH-target enzyme is not found in many of the fungal species, but the variations in its structure account for its various susceptibilities [108]. Due to the effective bioavailability of Olorofim, it can be administered through the oral and intravenous (I.V) route. Currently, only the oral dosage form is being tested, but the I.V. formulation will be soon available. The substance is found in many tissues, like in the kidney, liver, lung, as well as in brain, though in lesser amounts in the latter [108]. Orolofim demonstrated fungistatic activities against Aspergillus spp. at the initial stage, but after prolonged exposure, it exhibited fungicidal actions [110]. Olorofim also exhibits antifungal actions against various molds which includes Lomentospora prolificans, for which there is no current treatment available [111, 112] But, Olorofim does not exhibit any actions against Cryptococcus neoformans, Mucorales spp., and Candida spp. because of differences in the targeting of the site of infection by the drug [113].

In addition, tetrazoles like VT-1129 and VT-1598 have come into the picture, especially with the FDA approval of VT-1161 recently in 2022 for the treatment of vulvovaginal candidiasis [101]. VT-1161, also known as Oteseconazole, is administered orally to reduce the incidence of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis in females who are not of reproductive potential. VT-1598, another next-generation azole, shows a very broad spectrum of in vitro activity against C. auris, molds, as well as endemic fungi like Blastomyces dermatitidis, Histoplasma capsulatum, C. immitis, and Coccidioides posadasii [111, 114]. It has been granted QIDP (Qualified Infectious Disease Product), fast track, and orphan drug designation for the treatment of coccidioidomycosis by the FDA. Fosmanogepix (previously known as APX001) inhibits the GPI-anchored wall protein transfer 1. It has been known to show potent in vitro activity against Candida species, especially the echinocandin-resistant C. albicans and C. glabrata [115]. Clinical development has so far focused on its development in infections caused by Candida spp., Aspergillus spp., and some rare molds. Eyeing the recent clinical developments, the FDA has given fast track, QIDP, and orphan drug designation to fosmanogepix. Another novel anti-fungal drug, Rezafungin (previously called CD101), is from the echinocandin class of drugs. It is essentially a structural analogue of anidulafungin with a choline moiety at the C5 position, which gives it increased solubility and stability [116]. It has shown activity against WT (wild type) and azole-resistant Candida species and Aspergillus spp. [117, 118]. The FDA has provided Rezafungin fast track and QIDP designation for the prevention of fungal infections. In addition to this, the FDA has granted fast track, QIDP, and orphan drug designation for the treatment of invasive candidiasis. One of the major upcoming candidates is the encochleated AmB (CAMB), which is a novel formulation intended for oral administration. Cochleates assemble to form a multilayering composed of an array of phosphatidylserine (negatively charged lipid) and a divalent cation (Calcium). This structure protects against the degradation of AmB in the gut [119]. CAMB has also been granted fast track, QIDP, and orphan drug designation by the FDA.

While antifungal drug development is not always driven by the needs of endemic systemic mycoses, it is important to consider the role of new drugs in addressing these diseases. Diseases such as histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis, and talaromycosis are serious fungal infections that lack effective treatments [120]. The recent drug development efforts have yielded several new drugs that have shown promise in treating these infections [121]. For example, isavuconazole and voriconazole are now considered first-line therapies for invasive aspergillosis, which is a common complication of some endemic mycoses [122, 123]. In addition, new drugs such as fosmanogepix and VT-1598 have shown efficacy against a broad range of fungal pathogens, including those causing endemic systemic mycoses [121, 123].

Some of the novel antifungal drugs that have completed or are undergoing clinical trials are listed in Table 2. These drugs are being tested against a range of fungal infections, including serious conditions such as aspergillosis and cryptococcal infections, as well as less severe conditions such as vulvovaginal candidiasis, onychomycosis, and tinea pedis. The main goal of these clinical trials is to overcome the disadvantages that are associated with the treatment of resistant and recurrent fungal infections and additionally demonstrate better safety, efficacy, tolerance, broad spectrum of activity, and fewer drug-drug interactions.

Table 2.

Recently completed and currently undergoing clinical trials of novel antifungal drugs

| Agents | Class of drugs | Study title | Condition (s) | Intervention | Study initiation date | Date of completion | Study phase/type | NCT number | Inference* | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oteseconazole (VT-1161) | Azoles | A Study of Oral Oteseconazole (VT-1161) for the Treatment of Patients with Recurrent Vaginal Candidiasis (Yeast Infection) (VIOLET) | Recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis |

Drug: VT-1161 VT-1161 150 mg capsule Placebo matching capsule |

August 23, 2018 | August 3, 2021 | Phase-3 | NCT03561701 | A higher value of efficacy was achieved in patients receiving VT-1161 when compared with the placebo group | Approved by FDA on 1st April 2022 for the treatment of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis (RVVC) |

| Study of Oral Oteseconazole (VT-1161) for Acute Yeast Infections in Patients with Recurrent Yeast Infections (ultraVIOLET) | Recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis |

Drug: Oteseconazole (VT-1161) 150 mg capsule Drug: Fluconazole 150 mg capsule Drug: Placebo |

March 13, 2019 | December 2, 2020 | Phase-3 | NCT03840616 | Oteseconazole was found to be more efficacious than Fluconazole/Placebo. Some non-serious adverse events like nausea, pyrexia, UTI, bacterial vaginosis, sinusitis, headache, and rash were observed | |||

| A Study to Evaluate Oral VT-1161 in the Treatment of Patients with Recurrent Vaginal Candidiasis (Yeast Infection) | Recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis |

Drug: VT-1161 Drug: Placebo |

February 10, 2015 | November 9, 2016 | Phase-2 | NCT02267382 | VT-1161 was well-tolerated and exhibited a good safety profile. Adverse event incidence in the VT-1161 arm was much lower than that of the placebo. Overall, it was proved to be more efficacious than placebo | |||

| A Study to Assess the Efficacy and Safety of Oral VT-1161 in Patients with Toenail Onychomycosis | Onychomycosis |

Drug: VT-1161 Placebo |

February 17, 2015 | July 7, 2017 | Phase-2 | NCT02267356 | An effective nail clearance rate was seen after treatment with VT-1161 | |||

| Oral VT-1161 Efficacy and Safety in Patients with Moderate to Severe Interdigital Tinea Pedis | Tinea Pedis |

Drug: VT-1161 placebo |

August 2013 | December 2014 | Phase-2 | NCT01891305 | Clinical and mycological cure was achieved in patients receiving VT-1161, while none of the patients in the placebo group could recover. No mortality was reported. Non-serious adverse events included Herpes Zoster and influenza | |||

| Rezafungin (CD 101) | Echinocandins (Antibiotics) | CD101 Compared to Caspofungin Followed by Oral Step Down in Subjects with Candidemia and/or Invasive Candidiasis-Bridging Extension |

-Candidemia -Mycoses -Fungemia -Invasive Candidiasis |

Drug: CD101 Drug: Caspofungin Drug: Fluconazole Drug: intravenous placebo Drug: oral placebo |

July 26, 2016 | July 2019 | Phase-2 | NCT02734862 | The drug showed safety, efficacy, and tolerability while being administered once a week when compared with once-daily CAS plus fluconazole for the treatment of candidemia and invasive candidiasis | FDA has granted fast track and QIDP designation for the prevention of fungal infections. Also, it has been granted fast track, QIDP, and orphan drug designation for the treatment of invasive candidiasis |

| Study of Rezafungin Compared to Standard Antimicrobial Regimen for Prevention of Invasive Fungal Diseases in Adults Undergoing Allogeneic Blood and Marrow Transplantation (ReSPECT) |

Candidemia Mycoses Fungal Infection Fungemia Invasive Candidiasis Pneumocystis Mold Infection Invasive Fungal Disease Prophylaxis of Invasive Fungal Infections Aspergillus |

Drug: Rezafungin for Injection Drug: Posaconazole Drug: Fluconazole Drug: Trimethoprimsulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX) Drug: Intravenous Placebo Drug: Oral Placebo |

May 11, 2020 | March, 2022 | Phase 3 | NCT04368559 | Recruitment in process | |||

|

MAT2203 (Encochleated Amphotericin B) |

Novel nanoparticle-based encochleated AmB (CAmB) formulation | Oral Encochleated Amphotericin B (CAMB/MAT2203) in the Treatment of Vulvovaginal Candidiasis (VVC): Safety and Efficacy |

-Vulvovaginitis -Yeast infection -Vaginal candidiasis, vulvovaginal |

Drug: Oral Encochleated Amphotericin B (CAMB) lipid-crystal nano-particle formulation amphotericin B Other name: MAT2203 Drug: Fluconazole |

November 2016 | May 2017 | Phase-2 | NCT02971007 | A higher percentage of mycological eradication was seen in patients administered with Fluconazole when compared with CAMB. Clinical cure was achieved in a greater percentage of patients in the Fluconazole group compared to the CAMB group. No mortality was reported in any of the groups. Non-serious adverse events included diarrhea, nausea, bacterial vaginosis, and urinary tract infection | The FDA granted MAT2203 as a Qualified Infectious Disease Product (QIDP) with fast track status, with the potential for Orphan Drug Designation |

| CAMB/MAT2203 in Patients with Mucocutaneous Candidiasis (CAMB) | Candidiasis, chronic mucocutaneous | Drug: Amphotericin B | September 2016 | December 31, 2022 | Phase-2 | NCT02629419 | Oral CAMB was able to reduce vaginal and tongue fungal load. The drug showed good efficacy with high tolerability and safety | |||

| Encochleated Oral Amphotericin for Cryptococcal Meningitis Trial (EnACT) (EnACT) | Cryptococcal meningitis |

Drug: MAT2203 Drug: Amphotericin B |

October 24, 2019 | October 2022 |

Phase-1 Phase-2 |

NCT04031833 | Oral CAMB showed a good safety profile and was well-tolerated when compared with IV amphotericin B | |||

| Fosmanogepix (APX001) | Glycosyl phosphatidylinositol (GPI) inhibitor | A Study to Learn About the Study Medicine (Called Fosmanogepix/ PF-07842805) in People with Candidemia and/or Invasive Candidiasis |

Candidemia candidiasis, invasive |

Drug: PF-07842805 Drug: Caspofungin Drug: Fluconazole Drug: Placebo |

December 5, 2022 | February 10, 2026 | Phase 3 | NCT05421858 | Recruitment has not started yet | The FDA has granted fast track, Qualified Infectious Disease Product (QIDP), and orphan drug designation to fosmanogepix for the treatment of invasive candidiasis, scedosporiosis, fusariosis, coccidioidomycosis, invasive aspergillosis, and mucormycosis, cryptococcosis |

| Open-label Study of APX001 for Treatment of Patients with Invasive Mold Infections Caused by Aspergillus or Rare Molds (AEGIS) | Invasive fungal infections | Drug: fosmanogepix | January 4, 2020 | October 2021 | Phase 2 | NCT04240886 | Currently recruiting | |||

| An Efficacy and Safety Study of APX001 in Non-Neutropenic Patients with Candidemia | Candidemia | Drug: APX001 | October 3, 2018 | July 2, 2020 | Phase 2 | NCT03604705 | Overall, 80% treatment success was achieved. Mortality of 23.81% was observed. Serious adverse events were seen including cardio-respiratory arrest, septic shock, bacteraemia, necrotising fasciitis, urinary tract infection, among others. Non-serious adverse events like diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, pyrexia, hydronephrosis, pleural effusion and dyspnea were also observed | |||

| Olorofim (F901318) | Orotomides acts by inhibition of dihydroorotate dehydrogenase | Olorofim Aspergillus Infection Study (OASIS) | Invasive aspergillosis |

Drug: Olorofim Drug: AmBisome® |

November 30, 2021 | March 4, 2025 | Phase 3 | NCT05101187 | Recruitment has not started yet | The FDA granted orphan drug and breakthrough therapy designation. Orphan drug designation also granted by The European Medicine Agency Committee for Orphan Medicinal Products |

| Evaluate F901318 Treatment of Invasive Fungal Infections in Patients Lacking Treatment Options (FORMULA-OLS) | Invasive fungal infections | Drug: F901318 | June 6, 2018 | April 2023 | Phase 2 | NCT03583164 | Currently recruiting | |||

| Ibrexafungerp (SCY-078) | Glucan synthase inhibitor | Coadministration of Ibrexafungerp (SCY-078) with Voriconazole in Patients with Invasive Pulmonary Aspergillosis: A Safety and Efficacy Study | Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis |

Drug: SCY-078 Oral tablets of SCY-078 Other name: Ibrexafungerp Drug: Voriconazole Voriconazole IV vials or oral tablets Other: Oral Placebo Tablets Oral Placebo Tablets matching SCY-078 Other name: SCY-078 matching Placebo |

January 22, 2019 | November 26, 2022 | Phase-2 | NCT03672292 | Recruiting in process | FDA approved on June 1, 2021, for 1-day oral treatment of vaginal yeast infection |

| Dose-Finding Study of Oral Ibrexafungep (SCY-078) vs. Oral Fluconazole in Subjects with Acute Vulvovaginal Candidiasis (DOVE) | Candida vulvovaginitis |

Drug: Fluconazole Drug: SCY-078 |

August 1, 2017 | May 4, 2018 | Phase-2 | NCT03253094 | Ibexafungerp was well-tolerated and exhibited a good safety profile. The most common adverse events seen were only mild gastrointestinal events. Overall, it showed comparable efficacy to fluconazole | |||

| Efficacy and Safety of Oral Ibrexafungerp (SCY-078) vs. Placebo in Subjects with Acute Vulvovaginal Candidiasis (VANISH 303) | Candida vulvovaginitis |

Drug: Ibrexafungerp Drug: Placebo |

January 4, 2019 | September 4, 2019 | Phase-3 | NCT03734991 | The overall success percentage of Ibrexafungerp was found to be better than placebo. No mortality was observed. One patient developed pneumonia and bronchial hyperactivity. Some non-serious adverse events include diarrhea, nausea, bacterial vaginosis, headache, and abdominal pain | |||

| Open-Label Trial to Assess the Efficacy and Safety of Oral Ibrexafungerp (SCY-078) in Patients with Candida Auris-Induced Candidiasis (CARES) |

-Candidiasis, invasive -Candidemia |

Drug: SCY-078 Oral SCY-078 |

November 15, 2017 | December 15, 2022 | Phase-3 | NCT03363841 | Recruiting in process | |||

| Oral Ibrexafungerp (SCY-078) Efficacy and Safety vs. Placebo in Subjects with Acute Vulvovaginal Candidiasis | Candida vulvovaginitis |

Drug: Ibrexafungerp Ibrexafungerp 300 mg BID for 1 day Other name: SCY-078 Drug: Placebo Matching Placebo |

July 7, 2019 | April 29, 2020 | Phase-3 | NCT03987620 | Successful clinical cure was achieved when compared with the placebo group. No adverse events that lead to death of the patients were reported. Non-serious adverse events like headache, nausea, and diarrhea were observed | |||

| Ibrexafungerp for the Treatment of Complicated Vilvovaginal Candidiasis | Candida vulvovaginitis |

Drug: Ibrexafungerp Ibrexafungerp 150 mg BID |

May 1, 2022 | November 30. 2024 | Phase 3 | NCT05399641 | Recruitment in process. No results posted yet | |||

| Efficacy and Safety of Oral Ibrexafungerp (SCY-078) vs. Placebo in Subjects with Acute Vulvovaginal Candidiasis (Vanish 306) | Candida vulvovaginitis |

Drug: Ibrexafungerp Placebo |

June 7, 2019 | April 29, 2020 | Phase 3 | NCT03987620 | Higher percentage of clinical cure was reported among patients receiving Ibrexafungerp when compared with the placebo group. No mortality was reported. Out of 298 patients, only 1 serious adverse event was observed | |||

| Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of Ibrexafungerp in Patients with Fungal Diseases That Are Refractory to or Intolerant of Standard Antifungal Treatment (FURI) |

Invasive candidiasis, mucocutaneous candidiasis, coccidioidomycosis, histoplasmosis, blastomycosis, chronic pulmonary aspergillosis, allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, invasive pulmonary aspergillosis, recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis, other emerging fungi |

Drug: Ibrexafungerp | April 1, 2017 | December, 2022 | Phase 3 | NCT03059992 | Recruitment in process |

*Table does not include data from clinical trials that have been withdrawn, terminated or which have completed the recruitment process but no results have been posted as yet

Conclusion and future perspectives

The increasing prevalence of invasive fungal infections, drug resistance, and adverse effects associated with current antifungal medications highlight the urgent need for novel therapies in the fungal domain. Although, due to the aforementioned reasons, it is not so simple to synthesize antifungal drugs, there are various agents that are in the end phase of development. Few of them demonstrate enhanced resistance profiles like Olorofim and SCY-078. The rest of the agents exhibit a primary benefit in the formulation and administration like MAT2203, SCY-078, and CD101. Additionally, Isavuconazole has more advantages compared to voriconazole due to its better safety profile, efficacy, fewer drug-drug interactions, and the fact that routine therapeutic drug monitoring is typically not required for isavuconazole, whereas voriconazole requires TDM to ensure safe and effective dosing [124, 125]. Lately, the novel class of antifungal drugs- Orotomides demonstrate less cross-resistance and enables administration through the oral route.

Various antifungal compounds are still undergoing development and are under pre-clinical and clinical trials. But more research is still necessary during the post-marketing phase to evaluate the safety, efficacy, and resistance in various populations. Other than that, more studies should be conducted to develop novel therapeutic strategies for fungal infections, for example, repurposing of medications, antifungal biological substances, and host-immune cell-targeted strategies.

Novel formulations and drug delivery systems for currently used antifungal medications can, in fact, allow the synthesis of therapeutic targets, which should result in better efficacy and lower toxicity, as well as better health outcomes. The same can be said for antifungal pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) concepts, where improved in vitro and in vivo PK/PD models, more precise medicinal antifungal PK/PD assumptions, and therapeutic evaluation can contribute to improvement in antifungal dosage and a higher chance of a positive outcome for individuals suffering from fungal infections.

For the past few years, there has also been a surge in research for repurposing as a way to speed up the development of antifungal drugs. Repurposing, which is also known as repositioning, involves the exploration of new therapeutic applications for existing medications, as opposed to the hard, protracted, and costly proposition of de novo drug creation. Repurposing enables the recognition of pharmaceuticals with established PK, PD, and safety profiles in individuals, which is affordable, faster, and more likely to succeed than the conventional discovery of novel drugs. As a result, repurposing studies can result in a rapid introduction of innovative antifungal medications, reducing the time between lab and patient. This is especially relevant in the case of multidrug-resistant and rising diseases, as evidenced by the recent rapid expansion of C. auris infections. The literature has numerous examples of research focused at the repurposing of current medications into antifungals [126–130]. These initiatives have actually employed the use of the accessibility of repurposing libraries, which are collections of many current medications that can be quickly searched for compounds with unique antifungal activity [131–138]. Moreover, the development of novel biopharmaceuticals for antifungal therapy has paved way for the possibility of novel alternate strategies especially keeping in mind the host–pathogen response. Above all, major considerations should be drawn upon the patient, who is in actual need of medication and support to cure the infection without hampering the quality of life.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Madhura Roy and Sonali Karhana share equal authorship of the paper.

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Rauseo AM, Coler-Reilly A, Larson L, Spec A (2020) Hope on the horizon: novel fungal treatments in development. Open Forum Infect Dis [Internet] 7(2). Available from: https://academic.oup.com/ofid/article/7/2/ofaa016/5700872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Denning DW, Bromley MJ. How to bolster the antifungal pipeline. Science [Internet] 2015;347(6229):1414–1416. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa6097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roemer T, Krysan DJ. Antifungal drug development: challenges, unmet clinical needs, and new approaches. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med [Internet] 2014;4(5):a019703. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a019703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilaberte Y, Aspiroz C, Carmen Alejandre M, Andres-Ciriano E, Fortuño B, Charlez L, et al (2014) Cutaneous sporotrichosis treated with photodynamic therapy: an in vitro and in vivo study. https://home.liebertpub.com/pho [Internet] 32(1):54–57. Available from: https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/pho.2013.3590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Havlickova B, Czaika VA, Friedrich M. Epidemiological trends in skin mycoses worldwide. Mycoses [Internet] 2008;51(SUPPL.4):2–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2008.01606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christenson JK, Peterson GM, Naunton M, Bushell M, Kosari S, Baby KE, et al. Challenges and opportunities in the management of onychomycosis. J Fungi. 2018;4(3):87. doi: 10.3390/jof4030087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khurana A, Sardana K, Chowdhary A. Antifungal resistance in dermatophytes: recent trends and therapeutic implications. Fungal Genet Biol. 2019;1(132):103255. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2019.103255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Piraccini BM, Rech G, Tosti A. Photodynamic therapy of onychomycosis caused by Trichophyton rubrum. J Am Acad Dermatol [Internet] 2008;59(5 SUPPL.):S75–S76. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perfect JR. The antifungal pipeline: a reality check. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017;16(9):603–616. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2017.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hasim S, Coleman JJ (2019) Targeting the fungal cell wall: current therapies and implications for development of alternative antifungal agents. 11(8):869–83. 10.4155/fmc-2018-0465. Available from: https://www.future-science.com/doi/10.4155/fmc-2018-0465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.von Lilienfeld-Toal M, Wagener J, Einsele H, Cornely OA, Kurzai O. Invasive fungal infection: new treatments to meet new challenges. Dtsch Arztebl Int [Internet] 2019;116(16):271. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2019.0271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwartz I, Reports TPCID (2018) The emerging threat of antifungal resistance in transplant infectious diseases. Springer [Internet]. [cited 2023 Apr 24]; Available from: https://idp.springer.com/authorize/casa?redirect_uri=https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11908-018-0608-y&casa_token=vfyTVsqUSy0AAAAA:61EEsLkTVG6Hpw1PxrYB7TwjOv03M1Z0nRZHd3NHh4Fm4uyTJe9xVPbdD_gWcP4as0rdpcKRgBi9FZau1g [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Hendrickson J, Hu C, Aitken S, disease NBC infectious (2019) Antifungal resistance: a concerning trend for the present and future. Springer [Internet]. [cited 2023 Apr 24]; Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11908-019-0702-9 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Azevedo MM, Faria-Ramos I, Cruz LC, Pina-Vaz C, Gonçalves RA. Genesis of azole antifungal resistance from agriculture to clinical settings. J Agric Food Chem. 2015;63(34):7463–7468. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b02728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berger S, Chazli Y El, Babu A, microbiology ACF in (2017) Azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus: a consequence of antifungal use in agriculture? frontiersin.org [Internet]. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2017.01024/full [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Burks C, Darby A, Gómez Londoño L, Momany M, Brewer MT (2021) Azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus in the environment: Identifying key reservoirs and hotspots of antifungal resistance. PLoS Pathogens 17(7):e1009711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Alexander BD, Johnson MD, Pfeiffer CD, Jiménez-Ortigosa C, Catania J, Booker R, et al. Increasing Echinocandin resistance in Candida glabrata: clinical failure correlates with presence of FKS mutations and elevated minimum inhibitory concentrations. Clin Infect Dis [Internet] 2013;56(12):1724–1732. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meis JF, Chowdhary A, Rhodes JL, Fisher MC, Verweij PE (2016) Clinical implications of globally emerging azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus. Philos Trans R Soc B: Biol Sci [Internet] 371(1709). Available from: https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rstb.2015.0460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Schwartz IS, Patterson TF. The emerging threat of antifungal resistance in transplant infectious diseases. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2018;20(3):2. doi: 10.1007/s11908-018-0608-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ader F, Nseir S, Le Berre R, Leroy S, Tillie-Leblond I, Marquette CH, et al. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: an emerging fungal pathogen. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2005;11(6):427–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2005.01143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Posteraro B, Torelli R, de Carolis E, Posteraro P, Sanguinetti M (2011) Update on the laboratory diagnosis of invasive fungal infections. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis [Internet]. 3(1). Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC3103235/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Kontoyiennis DP, Marr KA, Park BJ, Alexander BD, Anaissie EJ, Walsh TJ, et al. Prospective surveillance for invasive fungal infections in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients, 2001–2006: overview of the transplant-associated infection surveillance network (TRANSNET) database. Clin Infect Dis [Internet] 2010;50(8):1091–100. doi: 10.1086/651263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gintjee TJ, Donnelley MA, Thompson GR. Aspiring antifungals: review of current antifungal pipeline developments. J Fungi. 2020;6(1):28. doi: 10.3390/jof6010028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patterson TF, Thompson GR, Denning DW, Fishman JA, Hadley S, Herbrecht R, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of Aspergillosis: 2016 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis [Internet] 2016;63(4):e1–60. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mohr J, Johnson M, Cooper T, Lewis JS, Ostrosky-Zeichner L. Current options in antifungal pharmacotherapy. Pharmacotherapy: J Human Pharmacol Drug Therapy [Internet] 2008;28(5):614–45. doi: 10.1592/phco.28.5.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stone NRH, Bicanic T, Salim R, Hope W. Liposomal Amphotericin B (AmBisome®): a review of the pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, clinical experience and future directions. Drugs. 2016;76(4):485–500. doi: 10.1007/s40265-016-0538-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barret JP, Ramzy PI, Heggers JP, Villareal C, Herndon DN, Desai MH. Topical nystatin powder in severe burns: a new treatment for angioinvasive fungal infections refractory to other topical and systemic agents. Burns. 1999;25(6):505–508. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(99)00037-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wingard JR, White MH, Anaissie E, Raffalli J, Goodman J, Arrieta A. A randomized, double-blind comparative trial evaluating the safety of liposomal Amphotericin B versus Amphotericin B lipid complex in the empirical treatment of febrile neutropenia. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31(5):1155–1163. doi: 10.1086/317451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holz RW. The effects of the polyene antibiotics nystatin and Amphotericin B on thin lipid membranes. Ann N Y Acad Sci [Internet] 1974;235(1):469–479. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1974.tb43284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Kruijff B, Gerritsen WJ, Oerlemans A, van Dijck PWM, Demel RA, van Deenen LLM. Polyene antibiotic-sterol interactions in membranes of Acholeplasma laidlawii cells and lecithin liposomes. II. Temperature dependence of the polyene antibiotic-sterol complex formation. Biochim Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes. 1974;339(1):44–56. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(74)90331-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carolus H, Pierson S, Lagrou K, Van Dijck P. Amphotericin B and other polyenes—discovery, clinical use, mode of action and drug resistance. J Fungi. 2020;6(4):321. doi: 10.3390/jof6040321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cornely OA, Vehreschild JJ, Ullmann AJ. Is there a role for polyenes in treating invasive mycoses? Curr Opin Infect Dis [Internet] 2006;19(6):565–570. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e328010851d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cassone A, Mason RE, Kerridge D. Lysis of growing yeast-form cells of Candida albicans by echinocandin: a cytological study. Med Mycol. 1981;19(2):97–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kauffman CA, Carver PL. Update on echinocandin antifungals. Semin Respir Crit Care Med [Internet] 2008;29(2):211–219. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1063859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Carli L, Larizza L. Griseofulvin. Mut Res/Rev Gen Toxicol. 1988;195(2):91–126. doi: 10.1016/0165-1110(88)90020-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gupta AK, Mays RR, Versteeg SG, Piraccini BM, Shear NH, Piguet V, et al. Tinea capitis in children: a systematic review of management. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol [Internet] 2018;32(12):2264–2274. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Waldorf AR, Polak A. Mechanisms of action of 5-fluorocytosine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1983;23(1):79–85. doi: 10.1128/aac.23.1.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Polak A, Scholer HJ, Wall M. Combination therapy of experimental candidiasis, cryptococcosis and aspergillosis in mice. Chemotherapy [Internet] 1982;28(6):461–479. doi: 10.1159/000238138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Diasio RB, Bennett JE, Myers CE. Mode of action of 5-fluorocytosine. Biochem Pharmacol. 1978;27(5):703–707. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(78)90507-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Delma FZ, Al-Hatmi AMS, Brüggemann RJM, Melchers WJG, de Hoog S, Verweij PE, et al. Molecular mechanisms of 5-fluorocytosine resistance in yeasts and filamentous fungi. J Fungi. 2021;7(11):909. doi: 10.3390/jof7110909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rodrigues ML. The multifunctional fungal ergosterol. MBio. 2018;9(5):e01755–18. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01755-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hitchcock CA, Dickinson K, Brown SB, Evans EGV, Adams DJ. Interaction of azole antifungal antibiotics with cytochrome P-450-dependent 14α-sterol demethylase purified from Candida albicans. Biochem J [Internet] 1990;266(2):475–480. doi: 10.1042/bj2660475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Allen D, Wilson D, Drew R, Perfect J. Azole antifungals: 35 years of invasive fungal infection management. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2015;13(6):787–798. doi: 10.1586/14787210.2015.1032939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ryder NS, Mieth H. Allylamine antifungal drugs. Curr Top Med Mycol. 1992;4:158–88. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4612-2762-5_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lanyi JK, Plachy WZ, Kates M. Lipid interactions in membranes of extremely halophilic bacteria II Modification of the Bilayer Structure by Squalene. Biochem [Internet] 1974;13(24):4914–4920. doi: 10.1021/bi00721a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ivanov M, Ćirić A, Stojković D. Emerging antifungal targets and strategies. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(5):2756. doi: 10.3390/ijms23052756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mühlbacher JM. Naftifine: a topical allylamine antifungal agent. Clin Dermatol. 1991;9(4):479–485. doi: 10.1016/0738-081x(91)90076-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fisher MC, Hawkins NJ, Sanglard D, Gurr SJ. Worldwide emergence of resistance to antifungal drugs challenges human health and food security. Science (1979) [Internet] 2018;360(6390):739–742. doi: 10.1126/science.aap7999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Parapouli M, Vasileiadi A, Afendra AS, Hatziloukas E. <em>Saccharomyces cerevisiae</em> and its industrial applications. AIMS Microbiol. 2020;6(1):1–32. doi: 10.3934/microbiol.2020001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tollemar J. Need for alternative trial designs and evaluation strategies for therapeutic studies of invasive mycoses. Clin Infect Dis [Internet] 2001;33(1):95–106. doi: 10.1086/320876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Boucher HW, Talbot GH, Bradley JS, Edwards JE, Gilbert D, Rice LB, et al. Bad bugs, no drugs: no ESKAPE! An update from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis [Internet] 2009;48(1):1–12. doi: 10.1086/595011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pfaller M, Neofytos D, Diekema D, Azie N, Meier-Kriesche HU, Quan SP, et al. Epidemiology and outcomes of candidemia in 3648 patients: data from the Prospective Antifungal Therapy (PATH Alliance®) registry, 2004–2008. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;74(4):323–331. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jørgensen KJ, Gøtzsche PC, Johansen HK. Voriconazole versus amphotericin B in cancer patients with neutropenia. In: Jørgensen KJ, editor. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Chichester, UK: Wiley; 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gueta I, Loebstein R, Markovits N, Kamari Y, Halkin H, Livni G, et al. Voriconazole-induced QT prolongation among hemato-oncologic patients: clinical characteristics and risk factors. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;73(9):1181–1185. doi: 10.1007/s00228-017-2284-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cuenca-Estrella M. Antifungal drug resistance mechanisms in pathogenic fungi: from bench to bedside. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20(6):54–59. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Arendrup MC. Update on antifungal resistance in Aspergillus and Candida. Clin Microbiol Infect [Internet] 2014;20(6):42–48. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kanafani ZA, Perfect JR. Resistance to antifungal agents: mechanisms and clinical impact. Clin Infect Dis [Internet] 2008;46(1):120–128. doi: 10.1086/524071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cowen LE, Sanglard D, Howard SJ, Rogers PD, Perlin DS. Mechanisms of antifungal drug resistance. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med [Internet] 2015;5(7):a019752. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a019752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pfaller MA. Antifungal drug resistance: mechanisms, epidemiology, and consequences for treatment. Am J Med. 2012;125(1):S3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ashbee HR, Barnes RA, Johnson EM, Richardson MD, Gorton R, Hope WW. Therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) of antifungal agents: guidelines from the British Society for Medical Mycology. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69(5):1162–1176. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yagasaki K, Gando S, Matsuda N, Kameue T, Ishitani T, Hirano T, et al. Pharmacokinetics and the most suitable dosing regimen of fluconazole in critically ill patients receiving continuous hemodiafiltration. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29(10):1844–1848. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-1980-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gupta A, Lynch L, Kogan N, Cooper E. The use of an intermittent terbinafine regimen for the treatment of dermatophyte toenail onychomycosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23(3):256–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2008.03036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kabasakalian P, Katz M, Rosenkrantz B, Townley E. Parameters affecting absorption of griseofulvin in a human subject using urinary metabolite excretion data. J Pharm Sci. 1970;59(5):595–600. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600590504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Echeverria-Esnal D, Martín-Ontiyuelo C, Navarrete-Rouco ME, Barcelo-Vidal J, Conde-Estévez D, Carballo N, et al. Pharmacological management of antifungal agents in pulmonary aspergillosis: an updated review. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2022;20(2):179–197. doi: 10.1080/14787210.2021.1962292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Walsh TJ, Seibel NL, Arndt C, Harris RE, Dinubile MJ, Reboli A, et al. Amphotericin B lipid complex in pediatric patients with invasive fungal infections. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1999;18(8):702–708. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199908000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hoeprich PD. Clinical use of amphotericin B and derivatives: lore, mystique, and fact. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;14(Supplement_1):S114–S119. doi: 10.1093/clinids/14.supplement_1.s114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Anderson CM. Sodium chloride treatment of amphotericin B nephrotoxicity. Standard of care? West J Med. 1995;162(4):313. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hoppe JE, Antifungals Study Group Treatment of oropharyngeal candidiasis in immunocompetent infants: a randomized multicenter study of miconazole gel vs. nystatin suspension. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1997;16(3):288–293. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199703000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Flynn PM, Cunningham CK, Kerkering T, San Jorge AR, Peters VB, Pitel PA, ... Robinson P (1995) Oropharyngeal candidiasis in immunocompromised children: a randomized, multicenter study of orally administered fluconazole suspension versus nystatin. J Pediatr 127(2):322–328 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 70.Pons V, Greenspan D, Lozada-Nur F, McPhail L, Gallant JE, Tunkel A, ... Green S (1997) Oropharyngeal candidiasis in patients with AIDS: randomized comparison of fluconazole versus nystatin oral suspensions. Clin Infect Dis 24(6):1204–1207 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 71.Blomgren J, Berggren U, Jontell M. Fluconazole versus nystatin in the treatment of oral candidosis. Acta Odontol Scand. 1998;56(4):202–205. doi: 10.1080/00016359850142790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Keating GM, Figgitt DP. Caspofungin: a review of its use in oesophageal candidiasis, invasive candidiasis and invasive aspergillosis. Drugs. 2003;63:2235–2263. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200363200-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fotsing LND, Bajaj T (2021) Caspofungin. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing [PubMed]

- 74.Eschenauer G, DePestel DD, Carver PL. Comparison of echinocandin antifungals. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2007;3(1):71–97. doi: 10.2147/tcrm.2007.3.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gupta AK, Mays RR, Versteeg SG, Shear NH, Friedlander SF. Onychomycosis in children: safety and efficacy of antifungal agents. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35(5):552–559. doi: 10.1111/pde.13561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kreijkamp-Kaspers S, Hawke KL, van Driel ML. Oral medications to treat toenail fungal infection. JAMA. 2018;319(4):397–398. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.20160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chaudhary RG, Rathod SP, Jagati A, Zankat D, Brar AK, Mahadevia B. Oral antifungal therapy: emerging culprits of cutaneous adverse drug reactions. Indian Dermatology Online Journal. 2019;10(2):125. doi: 10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_353_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Folk A, Balta C, Herman H, Ivan A, Boldura OM, Paiusan L, ... Hermenean A (2017) Flucytosine and amphotericin B coadministration induces dose-related renal injury. Dose-Response 15(2):1559325817703461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 79.Jelen G, Tennstedt D. Contact dermatitis from topical imidazole antifungals: 15 new cases. Contact Dermatitis. 1989;21(1):6–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1989.tb04677.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Heel RC, Brogden RN, Speight TM, Avery GS. Econazole: a review of its antifungal activity and therapeutic efficacy. Drugs. 1978;16:177–201. doi: 10.2165/00003495-197816030-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yan Z, Liu X, Liu Y, Han Y, Lin M, Wang W, ... Hua H (2016) The efficacy and safety of miconazole nitrate mucoadhesive tablets versus itraconazole capsules in the treatment of oral candidiasis: an open-label, randomized, multicenter trial. PLoS One 11(12):e0167880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 82.Benfield P, Stephen P. Sulconazole: a review of its antimicrobial activity and therapeutic use in superficial dermatomycoses. Drugs. 1988;35:143–153. doi: 10.2165/00003495-198835020-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sohn CA. Evaluation of ketoconazole. Clin Pharm. 1982;1(3):217–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gupta AK, Lyons DC. The rise and fall of oral ketoconazole. Journal of Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery. 2015;19(4):352–357. doi: 10.1177/1203475415574970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Brass CJTRRD, Galgiani JN, Blaschke TF, Defelice R, O'reilly RA, Stevens DA. Disposition of ketoconazole, an oral antifungal, in humans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1982;21(1):151–158. doi: 10.1128/aac.21.1.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Amichai B, Grunwald MH. Adverse drug reactions of the new oral antifungal agents–terbinafine, fluconazole, and itraconazole. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37(6):410–415. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1998.00496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Pappas PG, Bradsher RW, Chapman SW, Kauffman CA, Dine A, Cloud GA, Dismukes WE. Treatment of blastomycosis with fluconazole: a pilot study. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20(2):267–271. doi: 10.1093/clinids/20.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Piérard GE, Arrese JE, Piérard-Franchimont C. Itraconazole. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2000;1(2):287–304. doi: 10.1517/14656566.1.2.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Abraham AO, Panda PK. Itraconazole induced congestive heart failure, a case study. Curr Drug Saf. 2018;13(1):59–61. doi: 10.2174/1574886312666171003110753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Re VL, III, Carbonari DM, Lewis JD, Forde KA, Goldberg DS, Reddy KR, et al. Oral azole antifungal medications and risk of acute liver injury, overall and by chronic liver disease status. Am J Med. 2016;129(3):283–291. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.10.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Raschi E, Poluzzi E, Koci A, Caraceni P, De Ponti F. Assessing liver injury associated with antimycotics: concise literature review and clues from data mining of the FAERS database. World J Hepatol. 2014;6(8):601. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v6.i8.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Saravolatz LD, Johnson LB, Kauffman CA. Voriconazole: a new triazole antifungal agent. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36(5):630–637. doi: 10.1086/367933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Epaulard O, Leccia MT, Blanche S, Chosidow O, Mamzer-Bruneel MF, Ravaud P, et al. Phototoxicity and photocarcinogenesis associated with voriconazole. Med Mal Infect. 2011;41(12):639–645. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2011.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Courtney R, Radwanski E, Lim J, Laughlin M. Pharmacokinetics of posaconazole coadministered with antacid in fasting or nonfasting healthy men. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48(3):804–808. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.3.804-808.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Cornely OA, Maertens J, Winston DJ, Perfect J, Ullmann AJ, Walsh TJ, et al. Posaconazole vs. fluconazole or itraconazole prophylaxis in patients with neutropenia. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(4):348–359. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lipner SR, Scher RK. Onychomycosis: treatment and prevention of recurrence. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(4):853–867. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.05.1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zane LT, Chanda S, Coronado D, Del Rosso J (2016) Antifungal agents for onychomycosis: new treatment strategies to improve safety. Dermatology Online Journal 22(3) [PubMed]

- 98.Gupta AK, Ryder JE, Cooper EA. Naftifine: a review. Journal of Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery. 2008;12(2):51–58. doi: 10.2310/7750.2008.06009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Scorzoni L, de Paula e Silva ACA, Marcos CM, Assato PA, de Melo WCMA, de Oliveira HC, et al. Antifungal therapy: new advances in the understanding and treatment of mycosis. Front Microbiol. 2017;8(JAN):36. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Miceli MH, Kauffman CA. Isavuconazole: a new broad-spectrum triazole antifungal agent. Clin Infect Dis [Internet] 2015;61(10):1558–15565. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Hoy SM. Oteseconazole: first approval. Drugs. 2022;82(9):1017–1023. doi: 10.1007/s40265-022-01734-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Barnes KN, Yancey AM, Forinash AB (2022) Ibrexafungerp in the treatment of vulvovaginal candidiasis. 10.1177/10600280221091301. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/10600280221091301 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 103.Sheng C, Zhang W. New lead structures in antifungal drug discovery. Curr Med Chem. 2011;18(5):733–766. doi: 10.2174/092986711794480113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Heath CH. Fungal infections: an infection control perspective. Healthcare Infection. 2002;7(4):138–150. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kang SJ, Park SJ, Mishig-Ochir T, Lee BJ (2014) Antimicrobial peptides: therapeutic potentials. 12(12):1477–86. 10.1586/147872102014976613. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1586/14787210.2014.976613 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 106.Victoria Castelli M, Gabriel Derita M, Noelí LS. Novel antifungal agents: a patent review (2013 - present) Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2017;27(4):415–426. doi: 10.1080/13543776.2017.1261113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Usoo Al, David Oliver J, Leslie Thain J, John Bromley M, Edward Morris Sibley G (2009) Dihydroorotate dehydrogenase as antifungal drug target and quinazolinone-based inhibitors thereof

- 108.Oliver JD, Thain JL, Bromley MJ, Sibley GEM, Birch M. U.S. Patent No. 9,034,887. Washington, DC: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Garavito MF, Narváez-Ortiz HY, Zimmermann BH. Pyrimidine metabolism: dynamic and versatile pathways in pathogens and cellular development. J Genet Genomics. 2015;42(5):195–205. doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.du Pré S, Beckmann N, Almeida MC, Sibley GEM, Law D, Brand AC, et al (2018) Effect of the novel antifungal drug F901318 (olorofim) on growth and viability of aspergillus fumigatus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother [Internet] 62(8). Available from: https://journals.asm.org/doi/10.1128/AAC.00231-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 111.Wiederhold NP, Patterson HP, Tran BH, Yates CM, Schotzinger RJ, Garvey EP. Fungal-specific Cyp51 inhibitor VT-1598 demonstrates in vitro activity against Candida and Cryptococcus species, endemic fungi, including Coccidioides species, Aspergillus species and Rhizopus arrhizus. J Antimicrob Chemother [Internet] 2018;73(2):404–408. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Biswas C, Law D, Birch M, Halliday C, Sorrell TC, Rex J, et al. In vitro activity of the novel antifungal compound F901318 against Australian Scedosporium and Lomentospora fungi. Med Mycol [Internet] 2018;56(8):1050–1054. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myx161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Jørgensen KM, Astvad KMT, Hare RK, Arendrup MC (2018) EUCAST determination of olorofim (F901318) susceptibility of mold species, method validation, and MICs. Antimicrob Agents Chemother [Internet] 62(8). Available from: https://journals.asm.org/doi/10.1128/AAC.00487-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]