Abstract

Background

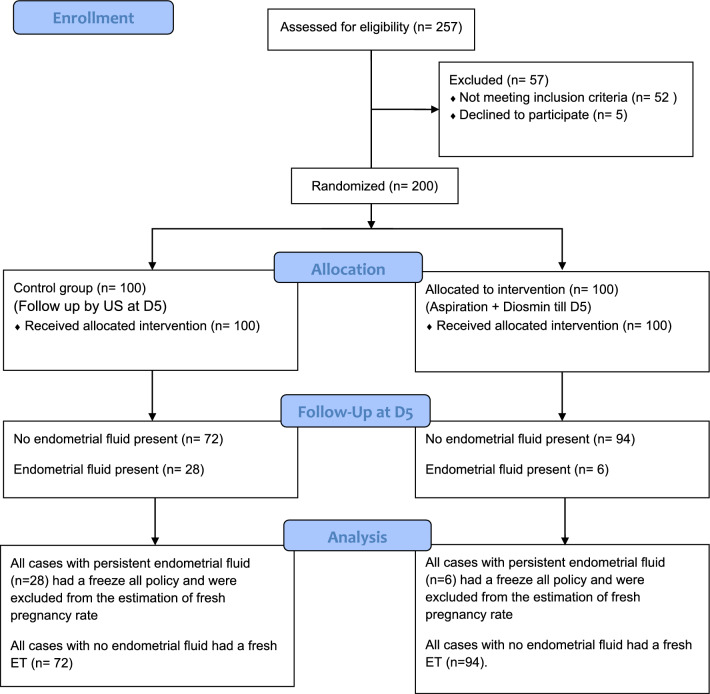

This was a prospective randomized controlled trial in 200 cases presented with endometrial cavity fluid at the day of oocyte retrieval at a private fertility center from 2013 to 2021. The cases were randomized at day of ovum pickup into 2 groups: Group 1 (control group) (n = 100): conventional management with follow-up and reassessment by transvaginal ultrasound on day 5. Group 2 (interventional group) (n = 100): aspiration of the fluid was done and cases were given diosmin 500 mg 3 times per day till reassessment at embryo transfer day. In both groups, we proceeded with fresh embryo transfer if no fluid is present on day 5 or freeze-all policy if persistent fluid was detected.

Results

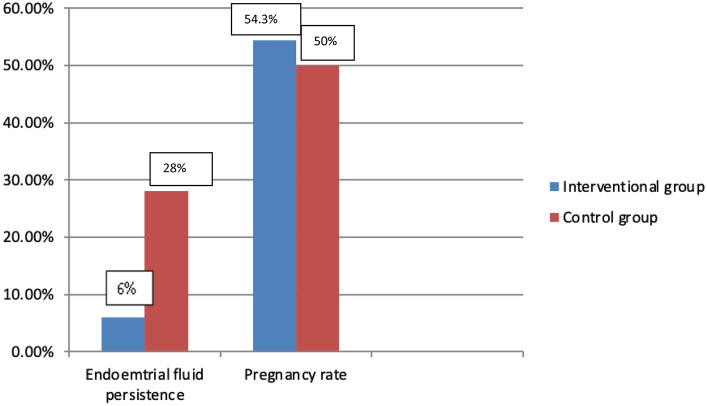

Endometrial fluid on the 5th day was significantly higher in the control group (28.0%) than in the interventional group (6.0%) (P < 0.001). Regarding pregnancy rate, although being higher in the interventional group (54.3% vs 50.0%), the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.5). It was found that the intervention was associated with risk reduction of endometrial fluid (OR = 0.168, 95% CI = 0.065–0.429, P < 0.001.

Conclusion

Aspiration of endometrial cavity fluid with diosmin intake increased the likelihood of fresh embryo transfer and with a slightly better pregnancy rate compared to conservative management.

Clinical trial number: NCT02158000, Date of registration: 6/6/2014, Date of initial enrollment (first patient recruiting): 1/11/2014, URL: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02158000.

Keywords: Endometrial fluid, Diosmin, Complications of ART cycles

Background

A healthy live birth of a child is the main target for assisted reproductive techniques [1]. Despite the increasing number of studies in the field of assisted reproduction, the live birth rates are still lower than our expectation (30% per oocyte retrieval) [2]. To achieve this goal, variable related & unrelated factors must be considered [1].

Different infertile couples’ data as history of the case, ovarian reserve markers, treatment and different procedures history are crucial to achieve this. We rely on all these data for achieving a proper decision-making solution concerning each case. Our objective was to have a healthy baby with the shortest route possible with the fewest complications [3, 4].

The cause of implantation failure requires study of many variables. One of these reasons is the identification of endometrial cavity fluid [5]. The presence of this fluid has been associated with a decline in implantation & pregnancy rates and an increased cancelation cycle rate, especially with presence of hydrosalpinx due to reflux as proved by many previous studies [6–9].

Tubal pathology as a contributor to infertility per se can be related to endometrial fluid detection even in the lack of hydrosalpinx [7].

The origin of the fluid may also be due to ascending cervical mucus [10], a consequence of abnormal endometrial growth with simulation protocols [11], or a result of subclinical infection in the uterus as a whole or just the endometrium [12]. Sometimes during ovarian stimulation, this fluid can be present for a few days then resolution occurs [13].

Very few studies have investigated endometrial cavity fluid, and most of them have studied fresh cycle transfer. Is there a difference if the endometrial fluid is present in fresh or frozen cycles? The answer is still vague [5].

The endometrial cavity fluid (ECF) consists of tubal fluid, endometrial discharge, mucus, or blood [14]. A few published papers [10, 11, 15, 16] described the visualization of ECF during controlled ovarian stimulation, following HCG administration and prior to embryo transfer.

Many retrospective studies have tested the effect of ECF on ART outcome. The reported frequency of ECF was 3.0–8.2% in these studies, but there are conflicting results about the effect of ECF presence on clinical pregnancy rate [17, 18].

As there are many ECF-related variables, the effect on the ART outcome is unpredicted, including when did ECF develop, what causes the underlying ECF formation, and the quantity of ECF. Variable factors means that the management of ECF should be case based and not a generalized treatment [14].

Timing of ECF development may also have an impact on the ART outcome. Several reports imply that the ECF accumulation during ovarian stimulation usually has a deleterious effect on the ART outcome [8, 9, 11, 18]. On the other hand, if detected after HCG injection, ECF develops transiently and vanishes on the day of embryo transfer, the ECF usually does not worsen the clinical pregnancy rate [6, 8, 9].

Diosmin was originally extracted in 1925 from the leaves of Scrophularia nodosa L., (Scrophulariaceae). Nowadays, it’s acquired by dehydrogenation of hesperidin. Diosmin has a variety of biological properties which is already established by various in vitro and in vivo studies. It has a role as an antioxidant, antihyperglycemic, anti-inflammatory, antimutagenic, and antiulcer agent [19–22].

Diosmin as an anti-inflammatory agent causes a marked decline in endothelial adhesion molecules in the plasma and decreases neutrophil activation, thus protecting the microcirculation from any deleterious effects [23, 24]. Furthermore, diosmin leads to a decline in the release of inflammatory mediators, such as thromboxane A2 (TxA2) & prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) [25] and a decline of T cell receptors [26].

We therefore hypothesized that aspiration of endometrial fluid may prevent recurrence and oral administration of diosmin might enhance capillary tension and reduce capillary leakage in cases of increased endometrial fluid cavity.

Patients and Methods

Study Design, Setting, Duration

This was a prospective randomized controlled trial conducted at a private fertility center from July 2013 to November 2021. It was a parallel design with allocation ratio 1:1. Inclusion criteria: All women undergoing ART cycles who presented with endometrial cavity fluid more than 3.5 mm of antero-posterior diameter at the day of ovum pickup in their ART cycles.

The study had ethical approval by the institutional review board of the fertility center (Hawaa—001-0056). Trial registration number is NCT02158000.

Participants/Materials, Methods

ART cases with endometrial cavity fluid detected on the day of oocyte retrieval were divided into 2 groups: Group 1 (control group) (100 cases): conventional management with just luteal phase support with vaginal progesterone 400 mg/12 h started on the day of ovum pickup with follow-up and reassessment by transvaginal ultrasound on day 5. Group 2 (study group) (100 cases): aspiration of the fluid was done by an intrauterine insemination catheter (Surgimedik) just after ovum pickup. This was guided by transvaginal ultrasound till complete aspiration of ECF then the cases were given diosmin 500 mg 3 times per day till day 5 and reassessment at that day. In both groups, fresh embryo transfer was conducted if fluid resolution had taken place on day 5 or freeze-all policy if fluid was present or re-accumulated.

All our patients had at least a transvaginal ultrasound with saline sono-hysterography before the cycle preceding the ovarian stimulation to exclude hydrosalpinxes or any endometrial cavity abnormalities. Some patients had already done HSG or dye test with diagnostic laparoscopy to exclude any distal tubal block.

2 blastocysts of good quality were transferred in patients of both groups in whom a fresh embryo transfer at day 5 was done.

Our main outcome was to study the persistence of endometrial fluid at Day 5 embryo transfer. Secondary outcome was to study the clinical pregnancy rate for all the patients Freeze-all policy.

Sample Size Calculation

The sample size was estimated using G*power software version 3.1.9.2 based on a study [27], who reported endometrial fluid persistence of 70% if no aspiration was done, and an expected 20% reduction in endometrial fluid persistence in case of aspiration. The total sample calculated was 200 (100 in each group). Alpha and power were adjusted at 0.05 and 0.8, respectively.

Random Allocation

In this study, randomization was done by a computer-generated randomization list. Included subjects were randomly allocated into two groups. Random allocation of recruited participants was executed in a ratio of 1:1. In total, 200 sealed identical envelopes were prepared; 100 envelopes for each group. Each participant was permitted to choose just one envelope to determine the group to which she was assigned. Randomization was performed by an assistant who was not part of the study. The statistician was blinded about the study & control groups.

Statistical Methods

Statistical analysis and data execution were done using SPSS version 25. (IBM, Armonk, New York, United States). Quantitative data were analyzed for normality using Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and direct data visualization methods. Categorical data were compared using the Chi-square test. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was done for endometrial fluid prediction. All statistical tests were two-sided. P values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

We did a small pilot study before the actual study for testing our theory for management. The actual recruitment for this study participants began in July 2014. The study assessed 257 cases for eligibility but then 57 cases were excluded. We had 52 cases not meeting the inclusion criteria and 5 cases who refused to participate. After the excluded cases we had 200 cases eligible for our study and were randomized for both groups (100 for each group) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of participants in the study

General Characteristics

No significant differences were noted between both groups regarding age (P = 0.086), husband's age (P = 0.229), marriage duration (P = 0.602), FSH duration (P = 0.732), and endometrial thickness (P = 0.611) (Table 1).

Table 1.

General characteristics in the studied groups

| Interventional group (n = 100) | Control group (n = 100) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | Mean ± SD | 29 ± 5 | 30 ± 7 | 0.086 |

| Husband age (years) | Mean ± SD | 34 ± 6 | 35 ± 7 | 0.229 |

| Marriage duration (years) | Median (range) | 6 (1–21) | 5 (1–24) | 0.602 |

| FSH duration (days) | Mean ± SD | 10 ± 2 | 10 ± 2 | 0.732 |

| Endometrial thickness (mm) | Mean ± SD | 8.5 ± 2 | 8.6 ± 1.9 | 0.611 |

Independent t-test was used. Mann Whitney U test was used for marriage duration

Outcome

Persistence of endometrial fluid on the 5th day was significantly higher in the control group (28.0%) than in the interventional group (6.0%) (P < 0.001). Pregnancy rate, although being higher in the interventional group (54.3% vs 50%), the difference was not statistically significant (Table 2, Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Endometrial fluid persistence and clinical pregnancy rate in the studied groups

| Interventional group (n = 100) | Control group (n = 100) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endometrial fluid persistence | n (%) | 6 (6.0) | 28 (28.0) | < 0.001 |

| Pregnancy rate* | n (%) | 51 (54.3) | 36 (50.0) | 0.586 |

Chi-square test was used

*Percentages were calculated excluding those with endometrial fluid (embryo freezing)

Fig. 2.

Endometrial fluid persistence and pregnancy rate in the studied groups

Prediction of Endometrial Fluid

Multivariate logistic regression analysis was evaluated for the prediction of endometrial fluid. It was found that the intervention was associated with risk reduction of endometrial fluid (OR = 0.168, 95% CI = 0.065–0.429, P < 0.001), even after controlling the effect of age, infertility duration, FSH stimulation days, and endometrial thickness (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis for prediction of endometrial fluid

| OR (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|

| Intervention | 0.168 (0.065–0.429) | < 0.001 |

| Age (years) | 1.012 (0.93–1.102) | 0.781 |

| Infertility duration (years) | 0.985 (0.887–1.093) | 0.771 |

| FSH days | 1.041 (0.83–1.304) | 0.73 |

| Endometrial thickness (mm) | 1.031 (0.841–1.263) | 0.771 |

OR, Odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% Confidence interval

It was found that the intervention was associated with risk reduction of endometrial fluid (OR = 0.168, 95% CI = 0.065–0.429, P < 0.001), even after controlling the effect of age, infertility duration, FSH stimulation days, and endometrial thickness

Discussion

In underdeveloped countries, the cost of ART cycles is high and not covered by health insurance in most of the patients. Means any one of any of the infertile couple. Hence, we are always trying to maximize the success of the procedure with the most reasonable, economic and effective way possible. To do so, we always look at any factor that may reduce the success rate and try to avoid it. One of the encountered problems in ART cycle is accumulation of endometrial cavity fluid during ovarian stimulation, at the day of HCG, at the day of ovum retrieval or at the day of embryo transfer. A recent met-analysis clarifies the harmful effect of endometrial cavity fluid on the clinical pregnancy rate of such cases [14].

We still don’t have a definite cause or mechanism of action for these cases. Data confirms confirmed that this condition occurs more in PCOS patients, cases with tubal factor of infertility and subclinical uterine infections [6, 8, 28].

Detection of ECF is usually diagnosed with the help of transvaginal ultrasound during controlled ovarian stimulation or at the time of ovum pickup or the time of embryo transfer. It’s usually diagnosed after detection of at least 3.5 mm of fluid in the antero-posterior diameter in the endometrial cavity [6].

Presence of this fluid at time of oocyte retrieval is usually managed by either cancellation with a freeze all policy or aspiration on the day of the retrieval or reassessment at the day of embryo transfer with either freeze all or aspiration [29].

Concerning the number of cases included in this study, to the best of our knowledge this study had the highest number of cases having ECF in a prospective study with a total number of 200 cases collected. On the other hand, most of the other studies were retrospective, with the most prominent number of cases in other studies were 25, 35, 38, 46, 69, 106 total cases [6–9].

Only one recent retrospective study in 2021 has managed to collect 3688 patients from their electronic medical records from 2009 to 2014. Only 2654 patients continued in the study after exclusion of cases with cancelled embryo transfer, missed information or aspiration of ECF was done [30].

Our study agrees with Levi et al. that ECF have occurred during gonadotropin stimulation phase in some cases and after HCG administration in other cases [9]. In contrast to the observation in other studies that ECF developed during ovarian stimulation only [11] or after HCG [10, 16–18].

Aspiration is a valid option for persistent ECF in some of the studies. We compared our results with cases of ECF accumulation, any study in which hydrosalpinx was aspirated was excluded.

Our results support similar pregnancy rate between cases after spontaneous resolution of ECF & aspiration of ECF with diosmin intake at the time of ovum pickup.

Griffiths et al. [28] reported that aspiration of excessive ECF immediately before embryo transfer in five women didn’t have any deleterious effects and all patients conceived. Another prospective study involving 132 cases undergoing IVF found no decline in embryo implantation rates after ECF aspiration immediately before embryo transfer [31].

Levi et al. [9] in their methodology mentioned that they did aspiration in some cases but didn’t mention the results and whether ECF accumulated again at the time of ET or not. Another recent study in 2018, on 10 women having ECF at the time of egg collection, aspiration was done and none of them had ECF on the day of embryo transfer and all of them had ET in the same cycle and 5 of them became pregnant [32].

In contrast to these findings, others [17, 18] reported that the aspiration of ECF and hydrosalpinx during ART cycles was not beneficial because of the fluid re-accumulation after aspiration.

As for the effect of ECF on pregnancy rate, most of the studies have the conclusion that ECF has no deleterious results on the clinical pregnancy rate if it develops after hCG trigger it disapppears on the day of embryo transfer [6, 9, 15]. We concluded the same effect, but in our study, we didn’t transfer if ECF was detected at day of ET and in such cases we did a freeze all policy.

On the other hand, Zhang et al. [30], in their retrospective study, concluded that ECF cases had significantly lower clinical rates of pregnancy (57% vs 63.5%; P < 0.001), live birth (48.4% vs 55.5%; P < 0.001) than patients without ECF. They also reported an interesting obstetric outcome that cases with ECF had a higher chance of gestational diabetes (22% vs 9%, P = 0.014). Though, there were no differences in gestational weeks at delivery or birth weight between both groups [30].

Overall, ECF aspiration just before embryo transfer or just after ovum pickup seems feasible for cases with ECF who do not want to do a freeze all followed by a frozen embryo transfer. The idea behind choosing to do it at the time of ovum pickup is that we can give time to reassess the re-accumulating ECF again at the day of embryo transfer at day 5.

The unique thing about our methodology is that we added Diosmin oral intake to decrease the capillary leakage in the endometrium and due to its anti-inflammatory effect. This effect is both advantageous to some theories for the etiology and pathophysiology of this ECF. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to use Diosmin for such an indication.

We were aiming to aspirate the already present ECF by the IUI catheter (mechanical intervention) and trying to prevent further ECF re-accumulation by using Diosmin (chemical intervention). Based on our study results, we believe that our combined intervention achieved a good result and is a right solution.

Conclusion

Aspiration of endometrial cavity fluid with diosmin intake increased the likelihood of fresh embryo transfer and has almost same pregnancy rate as compared to conservative management. This is a valuable option without increasing the cost and emotional burden of cancelling the cycle.

Limitations and Reasons for Caution

In our work we couldn't do a double blind as we have to do an intervention in the form of aspiration of the endometrial fluid by.

The condition is not very common. So, this was an adequate number after sample size estimation. But further studies are warranted.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our dedicated lab directors. Dr. Waleed Abdel lateef & Dr. Sahar Eissa for their continuous support.

Author Contributions

The authors have explained the intervention to the patients and had their consent. No personal information of the patients or details have been revealed. The authors have equally contributed in collecting the data and writing the research work.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific Grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability

according to the journal policy.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved: The study was approved by the institutional review board of the fertility center (Hawaa—001-0056) at 5/6/2013. All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013).

Informed Consent

The authors have explained the intervention to the patients and had their written consent and no personal information of the patients or details have been revealed.

Footnotes

Ahmed Samy Saad is an Assistant Professor; Khalid Abd Aziz Mohamed is an Assistant Professor.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Malchau SS, Henningsen AA, Loft A, Rasmussen S, Forman J, Nyboe Andersen A, et al. The long-term prognosis for live birth in couples initiating fertility treatments. Hum Reprod. 2017;32(7):1439–1449. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dex096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Geyter C, Calhaz-Jorge C, Kupka MS, Wyns C, Mocanu E, Motrenko T, Scaravelli G, Smeenk J, Vidakovic S, Goossens V. European IVF-monitoring Consortium (EIM) for the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE). ART in Europe, 2014: results generated from European registries by ESHRE. Hum Reprod. 2018;33:1586–1601. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dey242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haahr T, Esteves SC, Humaidan P. Poor definition of poor-ovarian response results in misleading clinical recommendations. Hum Reprod. 2018;1(33):979–980. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dey059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haahr T, Esteves SC, Humaidan P. Individualized controlled ovarian stimulation in expected poor-responders: an update. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2018;16(1):20. doi: 10.1186/s12958-018-0342-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gupta N, Bhandari S, Agrawal P, Ganguly I, Singh A. Effect of endometrial cavity fluid on pregnancy rate of fresh versusfrozen in vitro fertilization cycle. J Hum Reprod Sci. 2017;10(4):288–292. doi: 10.4103/0974-1208.223282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.He RH, Gao HJ, Li YQ, Zhu XM. The associated factors to endometrial cavity fluid and the relevant impact on the IVF/ET outcome. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2010;14(8):46. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-8-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chien LW, Au HK, Xiao J, Tzeng CR. Fluid accumulation within the uterine cavity reduces pregnancy rates in women undergoing IVF. Hum Reprod. 2002;17(2):351–356. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.2.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akman MA, Erden HF, Bahceci M. Endometrial fluid visualized through ultrasonography during ovarian stimulation in IVF cycles impairs the outcome in tubal factor but not PCOS patients. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(4):906–909. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levi AJ, Segars JH, Miller BT, Leondires MP. Endometrial cavity fluid is associated with poor ovarian response and increased cancellation rates in ART cycles. Hum Reprod. 2001;16(12):2610–2615. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.12.2610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharara FI, McClamrock FI. Endometrial fluid collection in women with hydrosalpinx after human chorionic gonadotrophin administration: a report of two cases and implication for management. Hum Reprod. 1997;12(12):2816–2819. doi: 10.1093/humrep/12.12.2816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharara FI, Prough SG. Endometrial fluid collection in women with PCOS undergoing ovarian stimulation for IVF: a report of four cases. J Reprod Med. 1999;44(3):299–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drbohlav P, Halkova E, Masata J, et al. The effect of endometrial infection on embryo implantation in the IVF and ET program. Ceska Gynekol. 1998;1998(63):181–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee RK, Yu SL, Chih YF, Tsai YC, Lin MH, Hwu YM, et al. Effect of endometrial cavity fluid on clinical pregnancy rate in tubal embryo transfer (TET) J Assist Reprod Genet. 2006;23:229–234. doi: 10.1007/s10815-006-9035-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu S, Shi L, Shi J. Impact of endometrial cavity fluid on assisted reproductive technology outcomes. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2016;132:278–283. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gürgan T, Urman B, Aksu T, Yarali H, Kisnisci HA. Fluid accumulation in the uterine cavity due to obstruction of the endocervical canal in a patient undergoing in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer. J Assist Reprod Genet. 1993;10(6):442–444. doi: 10.1007/BF01228097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andersen AN, Yue Z, Meng FJ, Petersen K. Low implantation rate after in-vitrofertilization in patients with hydrosalpinges diagnosed by ultrasonography. Hum Reprod. 1994;9(10):1935–1939. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a138362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bloechle M, Schreiner T, Lisse K. Recurrence of hydrosalpinges after transvaginal aspiration of tubal fluid in an IVF cycle with development of a serometra. Hum Reprod. 1997;12(4):703–705. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a138362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mansour RT, Aboulghar MA, Serour GI, Riad R. Fluid accumulation of the uterine cavity before embryo transfer: a possible hindrance for implantation. J In Vitro Fertil Embryo Transf. 1991;8:157–159. doi: 10.1007/BF01131707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Silambarasan T, Raja B. Diosmin, a bioflavonoid reverses alterations in blood pressure, nitric oxide, lipid peroxides and antioxidant status in DOCA-salt induced hypertensive rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2012;679(1–3):81–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bogucka-Kocka A, Woźniak M, Feldo M, Kockic J, Szewczyk K. Diosmin–isolation techniques, determination in plant material and pharmaceutical formulations, and clinical use. Nat Prod Commun. 2013;8(4):545–550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Senthamizhselvan O, Manivannan J, Silambarasan T, Raja B. Diosmin pretreatment improves cardiac function and suppresses oxidative stress in rat heart after ischemia/reperfusion. Eur J Pharmacol. 2014;736:131–137. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shalkami AS, Hassan MI, Bakr AG. Anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and anti-apoptotic activity of diosmin in acetic acid-induced ulcerative colitis. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2018;37(1):78–86. doi: 10.1177/0960327117694075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramelet AA. Pharmacologic aspects of a phlebotropic drug in CVI associated edema. Angiology. 2000;51(1):19–23. doi: 10.1177/000331970005100105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manthey JA. Biological properties of flavonoids pertaining to inflammation. Microcirculation. 2000;7(6 pt 2):S29–S34. doi: 10.1111/j.1549-8719.2000.tb00148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Labrid C. Pharmacologic properties of Daflon 500 mg. Angiology. 1994;45(6):524–530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Imam F, Al-Harbi NO, Al-Harbi MM, et al. Diosmin down regulates the expression of T cell receptors, proinflammatory cytokines and NF-κB activation against LPS induced acute lung injury in mice. Pharmacol Res. 2015;102:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2015.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nikolettos N, Asimakopoulos B, Vakalopoulos I, Simopoulou M. Endometrial fluid accumulation during controlled ovarian stimulation for ICSI treatment. A report of three cases. Case Rep Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2002;29(4):290–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Griffiths AN, Watermeyer SR, Klentzeris LD. Fluid within the endometrial cavity in an IVF cycle: a novel approach to its management. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2002;19(6):298–301. doi: 10.1023/A:1015785431828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.He RH, Zhu XM. How to deal with fluid in the endometrial cavity during assisted reproductive techniques. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2011;23(3):190–194. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e3283468b94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang WX, Cao LB, Zhao Y, Li J, Li BF, Lv JN, Yan L, Ma JL. Endometrial cavity fluid is associated with deleterious pregnancy outcomes in patients undergoing in vitro fertilization/intracytoplasmic sperm injection: a retrospective cohort study. Ann Transl Med. 2021;9(1):9. doi: 10.21037/atm-20-3623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van der Gaast MH, Beier-Hellwig K, Fauser BC, Beier HM, Macklon NS. Endometrial secretion aspiration prior to embryo transfer does not reduce implantation rates. Reprod Biomed Online. 2003;7(1):105–109. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)61737-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Al-Hussaini TK, Shaaban OM. Aspiration of endometrial cavity fluid at the time of egg collection. Middle East Fertil Soc J. 2018;23(4):354–356. doi: 10.1016/j.mefs.2018.04.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

according to the journal policy.