This study examined how structural microdomains comprising the Ca2+-activated Cl− channel encoded by Tmem16a or Anoctamin-1 (ANO1) interact with voltage-gated Ca2+ channel CaV1.2 in the plasma membrane and how Ca2+ release from IP3 receptors in the sarcoplasmic reticulum drive intracellular Ca2+ waves and force production of pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells in response to the vasoconstrictor agonist serotonin.

Abstract

Pulmonary arterial (PA) smooth muscle cells (PASMC) generate vascular tone in response to agonists coupled to Gq-protein receptor signaling. Such agonists stimulate oscillating calcium waves, the frequency of which drives the strength of contraction. These Ca2+ events are modulated by a variety of ion channels including voltage-gated calcium channels (CaV1.2), the Tmem16a or Anoctamin-1 (ANO1)-encoded calcium-activated chloride (CaCC) channel, and Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum through inositol-trisphosphate receptors (IP3R). Although these calcium events have been characterized, it is unclear how these calcium oscillations underly a sustained contraction in these muscle cells. We used smooth muscle–specific ablation of ANO1 and pharmacological tools to establish the role of ANO1, CaV1.2, and IP3R in the contractile and intracellular Ca2+ signaling properties of mouse PA smooth muscle expressing the Ca2+ biosensor GCaMP3 or GCaMP6. Pharmacological block or genetic ablation of ANO1 or inhibition of CaV1.2 or IP3R, or Ca2+ store depletion equally inhibited 5-HT-induced tone and intracellular Ca2+ waves. Coimmunoprecipitation experiments showed that an anti-ANO1 antibody was able to pull down both CaV1.2 and IP3R. Confocal and superresolution nanomicroscopy showed that ANO1 coassembles with both CaV1.2 and IP3R at or near the plasma membrane of PASMC from wild-type mice. We conclude that the stable 5-HT-induced PA contraction results from the integration of stochastic and localized Ca2+ events supported by a microenvironment comprising ANO1, CaV1.2, and IP3R. In this model, ANO1 and CaV1.2 would indirectly support cyclical Ca2+ release events from IP3R and propagation of intracellular Ca2+ waves.

Introduction

Pulmonary arterial cells constrict in response to agonists coupled to Gq-protein receptor signaling. This process is enhanced in animal models of pulmonary hypertension (PH) and human pulmonary arterial hypertension, where pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells are more depolarized and display higher intracellular calcium concentrations (Yuan et al., 1998a, 1998b; Lin et al., 2004; Yu et al., 2004; Dai et al., 2005; Hirenallur et al., 2008; Archer et al., 2010). Several ion channels are important for the normal contraction of pulmonary smooth muscle cells and contribute to the development of PH (Mandegar et al., 2002; Mandegar and Yuan, 2002; Yu et al., 2004; Moudgil et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2007; Archer et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2012; Yamamura et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2012; Xia et al., 2014; Mu et al., 2018). One key protein postulated to play an important excitatory role in agonist-mediated vascular smooth muscle tone is the Ca2+-activated Cl− channel (CaCC) encoded by the Tmem16a or Anoctamin-1 (ANO1) gene, which has also been implicated to play a major role in PH (Forrest et al., 2012; Sun et al., 2012; Leblanc et al., 2015; Papp et al., 2019). The dogmatic view about the role of ANO1 in electromechanical coupling has been the following (Large and Wang, 1996; Kitamura and Yamazaki, 2001; Leblanc et al., 2005, 2015; Bulley and Jaggar, 2014): (1) stimulation of a Gq protein-coupled receptor (GqPCR) by a specific agonist leads to the production of inositol-trisphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol resulting from the breakdown of the plasma membrane (PM) phospholipid phosphatidyl-inositol-bisphosphate (PIP2) catalyzed by the enzyme phospholipase C; (2) IP3 then binds to one or more of the three IP3 receptor subtypes expressed in vascular myocytes producing a robust global Ca2+ transient originating from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), which in turn activates ANO1; (3) stimulation of ANO1 then causes membrane depolarization due to an equilibrium potential for Cl− that is ∼25–30 mV more positive than the resting potential of the cells (approximately −50 mV; Aickin and Brading, 1982; Chipperfield and Harper, 2000; Sun et al., 2021); and (4) the depolarization triggered by ANO1 stimulates Ca2+ entry through voltage-gated Ca2+ channels encoded by CaV1.2, which in turn triggers actin–myosin interaction and contraction by stimulation of myosin light chain kinase.

Although several aspects of the working model described above are correct, the model is too simplistic to explain the complex patterns of Ca2+ dynamics observed in smooth muscle cells of intact arteries and veins from the pulmonary circulation. While the membrane depolarization and contraction of pulmonary vascular smooth muscle cells evoked by GqPCR activation involving agonists such as phenylephrine, serotonin, ATP, angiotensin II, or endothelin-1 are sustained (Yuan, 1997; Forrest et al., 2012; Sun et al., 2012), the underlying Ca2+ events are asynchronous, highly localized, and poorly propagating intracellular Ca2+ oscillations or waves (Guibert et al., 1996a, 1996b; Hamada et al., 1997; Hyvelin et al., 1998; Smani et al., 2001; Perez and Sanderson, 2005; Perez-Zoghbi and Sanderson, 2007; Henriquez et al., 2018). The disconnect between sustained depolarization and transient, oscillating Ca2+ signals suggests that our understanding of pulmonary arterial smooth muscle contraction is incomplete. Since it is well established that the frequency of Ca2+ oscillations dictates the strength of contraction, it is important to understand how these Ca2+ events are initiated and propagated, as well as the relationship between the ion channels involved.

As mentioned above, ANO1, CaV1.2, and IP3 receptors have all been shown to play important roles in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cell contraction, although the specific contribution and relationship between these channels to create Ca2+ oscillations and sustained contractions is not fully understood. Here, we propose that these proteins are localized within microdomains where they form a subcellular signaling complex that supports the Ca2+ oscillations and corresponding contraction. This is not without precedence, as recent reports demonstrated the presence of signaling complexes that include ANO1 and IP3R in dorsal root ganglion neurons (Takayama et al., 2015; Shah et al., 2020). It was demonstrated that ANO1 is not activated by calcium entry through either CaV1.2 or TRPV1 but rather requires Ca2+ release from IP3R. In cerebral arteries, ANO1 is coupled to TRPC6 to support vasoconstriction (Wang et al., 2016). Here, we sought to investigate whether similar signaling microdomains exist in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells.

An additional purpose of this study was to solidify the involvement of ANO1 in agonist-mediated vasoconstriction. Evidence supporting a role for ANO1 in the vasoconstriction mediated by agonists has largely stemmed from studies reporting a significant attenuation by both classical and newer generations of CaCC/ANO1 blockers. Several of the newer generation of inhibitors (De La Fuente et al., 2008; Namkung et al., 2011; Huang et al., 2012; Oh et al., 2013) have been suggested to produce non-specific effects as reported by Boedtkjer et al. (2015), who showed that T16AInh-A01, CaCCInh-A01, and MONNA all produced a vasorelaxation of precontracted arteries in the “absence” of a transmembrane Cl− gradient. T16AInh-A01 also directly blocked macroscopic L-type Ca2+ current recorded in A7r5 smooth muscle cells and high KCl-induced contractions in intact arteries, while MONNA hyperpolarized non-stimulated resting vascular smooth muscle through an unknown mechanism (Boedtkjer et al., 2015). Thus, there is a question of whether the participation of ANO1 in electromechanical coupling and the development of arterial smooth muscle tone has been overestimated.

In this study, we used conditional smooth muscle–specific and inducible ANO1 knockout mice to define the role of ANO1 in determining the contractile and intracellular Ca2+ signaling properties of endothelium-denuded mouse pulmonary arterial smooth muscle exposed to the agonist serotonin (5-HT) and test the effectiveness and specificity of CaCCInh-A01. Our data show that suppressing ANO1, CaV1.2, or Ca2+ release from IP3R-sensitive Ca2+ stores in the SR similarly reduced the contraction to 5-HT by ∼50–60%. Asynchronous Ca2+ oscillations evoked by 5-HT were potently inhibited by similar approaches. Since our data demonstrate that ANO1, CaV1.2, and IP3R all functionally contribute to smooth muscle contraction, we investigated whether they are localized to microdomains. A specific ANO1 antibody was able to pulldown both CaV1.2 and IP3R in total protein lysates from pulmonary arteries, and advanced microscopy techniques revealed that CaV1.2 and IP3R colocalize with ANO1, especially near the PM. These experiments suggest that the stable 5-HT-induced pulmonary arterial contraction results from the integration of stochastic and localized Ca2+ events supported by a molecular architecture comprising ANO1, CaV1.2, and IP3R, which coordinates fundamental signaling optimized for excitation–contraction (EC) coupling.

Materials and methods

Animals and dissection of intact pulmonary arteries

All procedures pertaining to housing conditions and animal handling were approved by the University of Nevada Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol #20-06-1016-1) in accordance with the Update of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals by the National Research Council of the National Academies (8th edition, 2011). Five mouse strains were used in this study: (1) C57/BL6; (2) B6;129S-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm38(CAG-GCaMP3)Hze/J/SmMHC-CreERT2 (SMC-GCaMP3); (3) B6J.Cg-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm95.1(CAG-GCaMP6f)Hze/MwarJ/SmMHC-CreERT2 (SMC-GCaMP6f); (4) 129S-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm38(CAG-GCaMP3)Hze/J/SmMHC-CreERT2/ANO1fl/fl-ΔExons 5–6 (SMC-ANO1-kO-ΔEx5-6-GCaMP3); and (5) B6;129S-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm38(CAG-GCaMP3)Hze/J/SmMHC-CreERT2/ANO1fl/fl-ΔExon 12 (SMC-ANO-kO-ΔEx12/GCaMP3). For the four transgenic mouse models used, the induction of Cre recombinase expression was elicited by three consecutive daily IP injections with tamoxifen (TMX; MilliporeSigma; 80 mg/kg dissolved in safflower seed oil), and experiments were carried out between 50 and 60 d following the last TMX injection.

Upon removal, the heart and lungs were immediately immersed in cold (4°C) well-oxygenated Krebs solution of the following composition (in mM): 120 NaCl, 25 NaHCO3, 4.2 KCl, 1.2 KH2PO4, 1.2 MgSO4, 1.8 CaCl2, and 5.5 glucose (pH stabilized to 7.4 when bubbled with 95% O2–5% CO2). The main pulmonary artery was carefully dissected away from the heart and lungs and cleaned of any fat and connective tissue. For all contraction and Ca2+ imaging experiments, the endothelium was removed by passing a continuous stream of air bubbles through the lumen of the blood vessel via a syringe. This procedure abolished the endothelium-dependent relaxation caused by 1 μM acetylcholine in pulmonary arteries precontracted with 1 μM serotonin.

Contraction experiments in intact pulmonary arterial rings

Pulmonary arterial (PA) rings of ∼250 μm in length and <100 μm in diameter were mounted on a Four-Channel WPI Myobath II System to record isometric force. Each PA ring was mounted on a fixed stainless-steel pin at one end and to a stainless-steel triangular hook at the other end, itself hooked to a force transducer attached to a holder equipped with fine micropositioning to stretch the artery to a desired basal tension. Once mounted, the ring was immersed in a heated water-jacketed chamber filled with 30 ml of Krebs solution (composition identical to that described in the previous section) bubbled with 95% O2–5% CO2 (pH 7.4) and maintained at 37°C. The analog signal from the force transducer was recorded and measured using an A/D data acquisition system (by means of one of two WPI TBM4 amplifiers, and one MP100 or MP100A-CE A/D system from BIOPAC Systems, Inc.) and Acknowledge (v.3.9; BIOPAC Systems) software running on a Windows 10-based PC. Each PA ring was equilibrated in normal Krebs solution for at least 30 min. During this period, basal tension was set to 1 g. After equilibration, the ring was submitted to two consecutive 10-min incubation challenges with high K+–Krebs solution to elicit smooth muscle contraction by membrane depolarization and assess the viability of the preparation; the two challenges were interspersed by a 20-min wash in normal Krebs. Preparations were rejected when peak contraction was more than two standard deviations away from the mean. The high K+–Krebs solution was prepared by replacing 80 mM NaCl with 80 mM KCl, yielding a final K+ concentration = 85.4 mM. Following the second high K+–Krebs solution challenge, the solution was switched to normal Krebs solution for 10 min before the experiment was begun. Experiments were initiated by incubating each PA ring for 10 min with vehicle (0.1% DMSO) or one of four pharmacological agents: 1 μM nifedipine (MilliporeSigma), 10 μM cyclopiazonic acid (CPA; MilliporeSigma), 1 μM xestospongin C (Abcam), or 10 μM CaCCInh-A01 (MilliporeSigma). This was followed by a protocol designed to generate a cumulative dose–response curve to the agonist 5-HT, which was directly added to the bath as a concentrated stock solution (final concentrations were 0.01, 0.03, 0.1, 0.3, 1, 10, and 30 μM). Incubation with each 5-HT concentration usually lasted ∼5–10 min. In separate experiments, we tested the effects of agents on the high K+ Krebs-mediated contraction. Once a plateau was reached during the second high K+–Krebs solution challenge, the preparation was then exposed to vehicle (0.1% DMSO), 1 μM nifedipine, or to four concentrations of CaCCInh-A01 added in sequence (1, 3, 10, and 30 μM), all directly added to the chamber as concentrated stock solutions dissolved in DMSO (0.1%). For each preparation, peak contraction measured in a specific condition (5-HT ± drug, or high K+–Krebs solution + drug) was normalized to the peak contraction evoked by the second high K+–Krebs solution challenge. Finally, for experiments designed to determine the total amount of Ca2+ stored in the SR, after the second challenge with high K+–Krebs solution, the solution was either changed to normal Krebs for 20 min (control) or for 10 min followed by a 10-min incubation with normal Krebs solution containing either 1 μM nifedipine or 10 μM CaCCInh-A01. For each of these conditions, the solution was then switched to Ca2+-free Krebs solution containing 100 μM EGTA and 10 μM CPA to block the SR Ca2+-ATPase, with or without 1 μM nifedipine or 10 μM CaCCInh-A01. The latter solution elicited a transient contraction produced by the transient release of Ca2+ from the SR. The transient contraction was integrated and normalized to the amplitude of the second challenge with a high K+–Krebs solution; this ratio was used as an indirect index of the total amount of Ca2+ stored in the SR.

Isolation of mouse pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells

Single smooth muscle cells were freshly isolated from the main trunk and secondary branches of mouse pulmonary arteries using a technique adapted from the acute method described by Pritchard et al. (2014) for rat PASMCs. In brief, dissected pulmonary arteries were first incubated for 1 h at 4°C in a dissociation medium (DM; description below) containing the enzyme papain (1.5 mg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich). The composition of the DM was the following (in mM): 110 NaCl, 5 KCl, 0.5 KH2PO4, 0.5 NaH2PO4, 10 NaHCO3, 0.16 CaCl2 (free [Ca2+] = 7.6 μM), 2 MgCl2, 0.5 EDTA, 10 D-glucose, 10 taurine, and 10 Hepes-NaOH (pH 7.4). The partially digested tissue was then incubated for 6 min at 37°C with DM containing papain (1.5 mg/ml; MilliporeSigma) and the reducing agent dithiothreitol or DTT (1 mg/ml; MilliporeSigma). This was followed by a final enzymatic step during which the pulmonary arteries were incubated for 5–10 min in DM containing collagenase type IA (1.0–1.5 mg/ml; MilliporeSigma) and protease type XIV (1 mg/ml; MilliporeSigma). The remaining tissue was subsequently rinsed twice in enzyme-free DM. Cells were then dispersed by gentle trituration of the remaining digested tissue for ∼2 min using a small-bore Pasteur pipette. The remaining supernatant containing PASMCs was stored for 2–6 h at 4°C until use for imaging or electrophysiological experiments.

Whole-cell patch clamp electrophysiology

Ca2+-activated Cl− currents (IClCa) were recorded from freshly isolated mouse pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (PASMC) using the conventional whole-cell configuration of the patch clamp technique using an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Molecular Devices), Digidata 1320A acquisition system (Molecular Devices) and pCLAMP 9 software (Molecular Devices). To reduce contamination of IClCa from other types of currents in our recordings, CsCl and tetraethylammonium chloride (TEA) were added to the pipette solution and TEA was added to the K+-free external solution. The external solution used in all patch-clamp experiments had the following composition (in mM): 126 NaCl, 10 Hepes (pH adjusted to 7.35 with NaOH), 8.4 TEA, 20 glucose, 1.2 MgCl2, and 1.8 CaCl2. The intracellular pipette was set to 1 μM free [Ca2+] by the addition of 10 mM BAPTA and 8.27 mM CaCl2, which was calculated using the calcium Chelator program MaxChelator (v. 2.51; Patton, 2010). The internal pipette solution contained the following (in mM): 20 TEA, 106 CsCl, 10 Hepes (pH adjusted to 7.2 with CsOH), 10 BAPTA, 8.27 CaCl2, 5 ATP.Mg, 0.55 MgCl2 (1 mM free [Mg2+]), and 0.2 guanosine-5′-triphosphate. Series resistance compensation was performed in all experiments. Cells were continuously superfused with the external solution at a flow rate of ∼1 ml/min. All electrophysiological experiments were performed at room temperature.

IClCa was evoked immediately upon rupture of the cell membrane and its voltage-dependent properties were monitored every 10 s by stepping from a holding potential (HP) of −50 to +90 mV for 1 s, followed by repolarization to −80 mV for 1 s. Current–voltage (I–V) relationships were constructed after ∼2 min of cell dialysis by stepping in 10 mV increments from HP to test potentials between −100 and +140 mV for 1 s, each step followed by a 1 s repolarizing step to −80 mV. For I–V relationships, IClCa was expressed as current density (pA/pF) by dividing the current amplitude measured at the end of each voltage clamp step by the cell membrane capacitance (Cm in pF), which was calculated by integrating the average of five consecutive capacitive current (IC) transients elicited by steps to −60 mV from HP = −50 mV and using the following equation: , where dt is time (in ms) and ΔV corresponds to the 10 mV hyperpolarizing steps.

Ca2+ imaging in intact pulmonary arteries

A freshly dissected endothelium-denuded pulmonary artery from a mouse expressing either GCaMP3 or GCaMP6f conditionally in smooth muscle cells was cut open and pinned down with its lumen facing up on a 35-mm Petri dish layered with Sylgard. The Petri dish was then moved to the stage of an upright Olympus BX50WI epifluorescence microscope where constant flow superfusion (∼1 ml/min) with a normal physiological salt solution (PSS; see composition below) was initiated using a Gilson Minipulse 3 peristaltic pump with solutions maintained at 37°C by means of a temperature-controlled water-jacketed glass coil circulated by a Cole Palmer Polystat Controller pump. The composition of the PSS was as follows (in mM): 135 NaCl, 10 NaHCO3, 4.2 KCl, 1.2 KH2PO4, 1.2 MgCl2, 1.8 CaCl2, 5.5 glucose, and 10 Hepes-NaOH (pH 7.35). The preparation was allowed to equilibrate for a minimum of 30 min before fluorescence imaging was started. Imaging of GCaMP3/GCaMP6f-expressing smooth muscle cells was performed from the luminal side of the artery by means of one of three water immersion objectives (LUMPlan FNL 60×/0.9 NA, 40×/0.75 NA, or 20×/0.5 NA). GCaMP3 or GCaMP6f was excited at a wavelength of 488 nm by a Lumencor IIluminator Spectra X solid-state light source transmitted to the microscope via an optical fiber. 500–1,000 images (512 × 512 pixels) were acquired at 31 frames/s by an Andor iXon EMCCD camera (Andor Technology) controlled by Andor SOLIS software (Andor Technology) running under a Windows 7 PC platform. Movie stack TIFF files were analyzed using public domain ImageJ (Schneider et al., 2012). Each stack was first submitted to background subtraction (30–50 roll ball radius) followed by two rounds of smoothing. Three spatio-temporal (ST) maps were then generated per movie by reslicing three areas of the image using the line function of ImageJ at a width of 3 pixels and using a 90° rotation and avoiding interpolation. The three lines used to create ST maps across the entire image were drawn perpendicularly to the long axis of the smooth muscle cells and in a few pilot studies along the cell axis. The latter strategy was used to assess potential intercellular propagation of Ca2+ transients. The fluorescence intensity of all cells was measured from ST maps using the line function of ImageJ at a width of 3 pixels. The fluorescence intensity profile was then plotted as a function of time and the data were transferred to Excel and OriginPro (v. 2021b; OriginLab) for data analysis. GCaMP3 or GCaMP6f fluorescence (F) was reported as F/F0, where F0 is baseline fluorescence. When photobleaching was apparent, traces were corrected by subtracting a straight line from the baseline and then adding a value of one to each data point. Time-dependent fluorescence intensity profiles were analyzed using the Gadgets Quick Peaks module of OriginPro. This feature allowed for automated detection and analysis of Ca2+ transients. The module was generally set for detection of peaks by height at the 20% default value, which was sometimes raised when Ca2+ transients were small and noisy. Peak height, integrated area under the curve, and full-width duration at half-maximum (FWHM) were calculated by OriginPro. The frequency in Hertz was calculated in Excel by dividing the number of Ca2+ transients detected by the total duration of the movie in seconds (16.13 or 32.26 s).

Confocal microscopy

Pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells were freshly isolated as described above and plated onto no. 1.5H microscope cover glass (Deckgläser). Cells were fixed with 3.2% formaldehyde/0.1% glutaraldehyde in a DM for 10 min at room temperature, rinsed three times with PBS, then blocked and permeabilized using a solution containing 0.1% Triton-X 100, 1% BSA, and 20% SEA block (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in PBS for 1 h at RT. Cells were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies: rabbit antibody to ANO1 (PA2290, 1:50; Boster Biological), mouse antibody to CaV1.2 (N263/31, 1:100; NeuroMab), or mouse antibody to IP3R (sc-377518, 1:100; Santa Cruz). Samples were washed with PBS three times and incubated with Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated goat anti-rabbit or Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibodies (1:1,000; Invitrogen) at room temperature for 1 h, then washed three to five times with PBS. Slides were imaged using an Olympus FluoView FV 1000 laser scanning confocal microscope with an Olympus 100× UPlanApo100XO 1.40 NA oil immersion objective or a Leica Stellaris 8 confocal microscope equipped with a 100× objective.

Superresolution nanomicroscopy

Sample preparation was performed as described above for immunolabeling with the addition of extra 15-min wash steps with PBS. Samples were mounted on glass depression slides with the wells filled with a Glox-MEA Imaging Buffer as outlined in Dixon et al. (2017) and the edges of the coverslip were sealed with Twinsil (Picodent). Images were acquired on a GSDIM imaging system (Leica) built around an inverted microscope (DMI6000B; Leica) using a 160× HCX Plan-Apochromat (1.47 NA) oil-immersion lens and an EMCCD camera (iXon3 897; Andor Technology). Lateral chromatic aberrations and astigmatism corrections are integrated into the Leica GSDIM systems in parallel to the objective, tube lens, and c-mount. Optimal image results were obtained through the interplay of these corrections. Images were acquired in both TIRF and epifluorescence modes. The incidence angle for the TIRF mode was 150 nm. 25,000–60,000 frames were acquired for each color. Dual color images were acquired sequentially, with the Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated signal (ANO1) acquired first followed by the Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated signal (either IP3R or CaV1.2).

Image reconstruction was performed using the ImageJ plugin ThunderSTORM (Ovesný et al., 2014) using the default settings. Colocalization and nearest-neighbor analyses were determined using the ThunderSTORM coordinate-based colocalization (CBC) algorithm. Clusters were analyzed using SR-Tesseler (Levet et al., 2015). The program segments the single-molecule localizations and identifies regions of higher density. Clusters were defined as regions with localizations 2.5 times greater than surrounding areas.

RNA extraction and qRT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted using Trizol (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was prepared using a high-capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems). Quantitative analysis of mRNA expression was performed on a QuantStudio3 system (Thermo Fisher Scientific). 20 μl reactions (1 μl cDNA, 200 nM [ANO1] or 500 nM [β-actin] of each forward and reverse primer, and SYBR Green PCR master mix, Applied Biosystems) were run in triplicate. The normalized mRNA expression was calculated according to the (2ΔΔCt) method.

Coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP)

For each experiment, ice-cold radioimmunoprecipitation buffer (RIPA) with a protease inhibitor cocktail was used to harvest lysate from pulmonary arteries pooled from five to six C57/BL6 mice. co-IP was performed using Pierce Protein A/G Agarose. Briefly, the pulmonary arterial lysate was incubated with rabbit anti-ANO1 polyclonal antibody (ab53212; Abcam) at 4°C overnight. 20 μl Protein A/G Agarose resin was added and incubated for another 2 h at room temperature to capture the antibody–antigen complex. Antibody bound resin was then centrifuged and washed with RIPA buffer and bound proteins were eluted using denaturing buffer. The boiled eluate was run on an SDS-polyacrylamide gel and protein samples were analyzed by Western blotting.

Protein analysis and Western blotting

Pulmonary artery from five to six C57/BL6 mice were homogenized and lysed in RIPA lysis buffer containing a cocktail of protease inhibitors. Proteins were separated in 4–12% NuPAGE (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and transferred into nitrocellulose membranes (0.45 µm; cat. no. 162-0215; Bio-Rad). The membranes were blocked with LI-COR Odyssey blocking buffer (part no. 92740000) in PBS (1:1) for 1 h at room temperature and incubated overnight at 4°C with the following primary antibodies (all diluted at 1:250 in LI-COR Odyssey blocking buffer in PBS [1:1] with 0.01% Tween-20): rabbit polyclonal ANO1 (ab53212; Abcam), rabbit monoclonal IP3R (D53A5; Cell Signaling Technology), mouse monoclonal polyclonal CaV1.2 (MAB13170; MilliporeSigma), and goat polyclonal actin (sc-1616; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The membranes were incubated with Alexa Fluor 680 or 800 conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG or donkey anti-goat (diluted 1:25,000 in LI-COR Odyssey blocking buffer in PBS [1:1] with 0.01% Tween-20) for 1 h at room temperature. Signals were detected using Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR) near infrared wavelengths using the 700 and 800 nm channels. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Statistical analysis

All pooled data are expressed as means with error bars representing the SEM. Raw data were imported into Excel and the means exported to OriginPro 2021b software (OriginLab Corp.) for plotting and testing of statistical significance between groups. Statistical significance between means was determined using paired or unpaired Student’s t test when two groups were compared, or one-way or two-way ANOVA for multiple group comparisons, and the Tukey’s post hoc test to determine which groups are statistically significant from each other. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. All graphs, images, and ionic current traces were uploaded to CorelDRAW 2021 for Mac for final processing of the figures.

Online supplemental material

Video 1 depicts the lack of spontaneous activity in an intact pulmonary artery from a conditional SMC-GCaMP3 mouse exposed to a normal external solution. Video 2 shows that a 5-min exposure to 1 μM 5-HT triggered asynchronous Ca2+ oscillations in the same pulmonary artery from a conditional SMC-GCaMP3 mouse as shown in Video 1. Video 3 is a Surface Plot video illustrating the initiation and propagation of Ca2+ waves in a single PASMC from an intact pulmonary artery from a conditional SMC-GCaMP3 mouse. Video 4 shows that a 10-min exposure to 10 μM CaCCInh-A01 in the presence of 5-HT had a profound inhibitory effect on Ca2+ oscillations in the same pulmonary artery from a conditional SMC-GCaMP3 mouse as shown in Videos 1 and 2.

Video 1.

Video depicting lack of spontaneous activity in an intact PA from a conditional SMC-GCaMP3 mouse exposed to normal external solution. Stacked images (512 × 512 pixels) from a subset (150 frames) of the original video (1,000 images) were recorded at a frame rate of 32 F/s. All images were background subtracted, smoothened, and pseudo-colored to the Red Hot LUT table in ImageJ.

Video 2.

Video showing that a 5-min exposure to 1 μM 5-HT triggered asynchronous Ca2+ oscillations in the same PA from a conditional SMC-GCaMP3 mouse as shown in Video 1. Stacked images (512 × 512 pixels) from a subset (150 frames) of the original movie (1,000 images) were recorded at a frame rate of 32 F/s. All images were background subtracted, smoothened, and pseudo-colored to the Red Hot LUT table in ImageJ.

Video 3.

Surface Plot video illustrating the initiation and propagation of Ca2+ waves in a single PASMC from an intact pulmonary artery from a conditional SMC-GCaMP3 mouse. Stacked images (512 × 512 pixels) from the original movie were first cropped to images of 115 × 115 pixels in size. All images were background subtracted, smoothened, and pseudo-colored to the 5 Ramps LUT table in ImageJ. The resulting 2-D video was then processed to a 3-D video using the Surface Plot feature of ImageJ. The movie was slowed down four times to 8 F/s from the original 32 F/s. The movie contains a sequence of 200 images from the original 1,000 images.

Video 4.

Video showing that a 10-min exposure to 10 μM CaCCInh-A01 in the presence of 5-HT had a profound inhibitory effect on Ca2+ oscillations in the same pulmonary artery from a conditional SMC-GCaMP3 mouse as shown in Videos 1 and 2. Stacked images (512 × 512 pixels) from a subset (150 frames) of the original video (1,000 images) were recorded at a frame rate of 32 F/s. All images were background subtracted, smoothened, and pseudo-colored to the Red Hot LUT table in ImageJ.

Results

ANO1 promotes agonist-mediated contraction of mouse pulmonary arteries

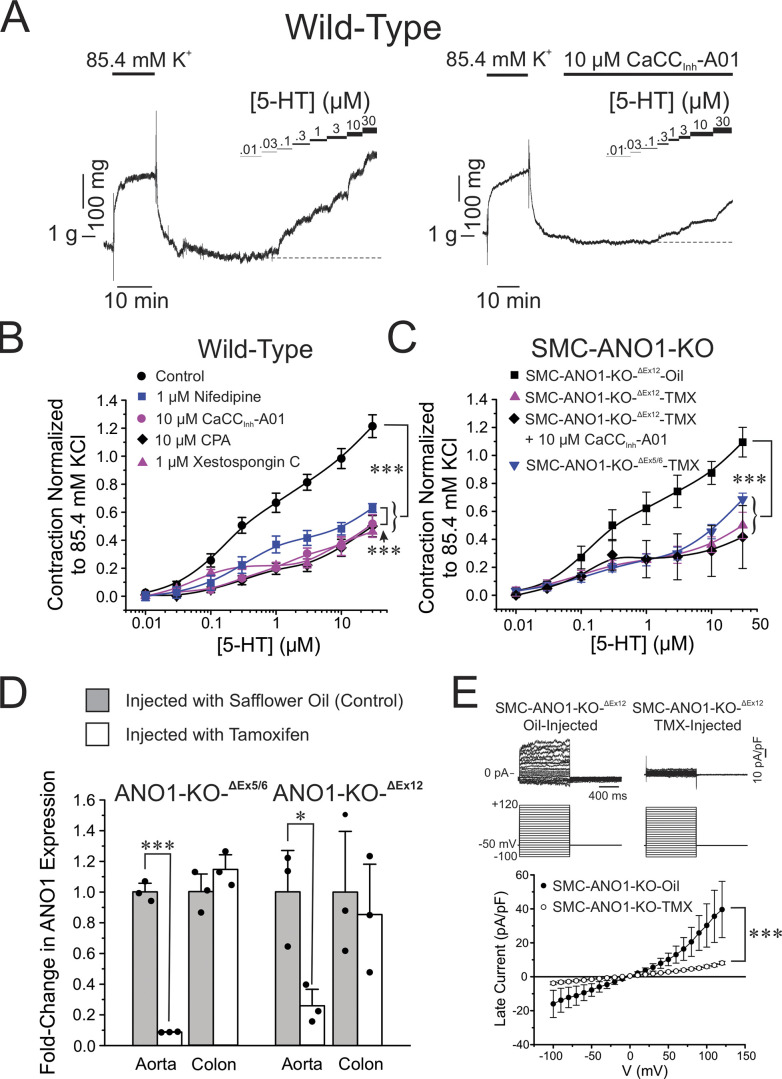

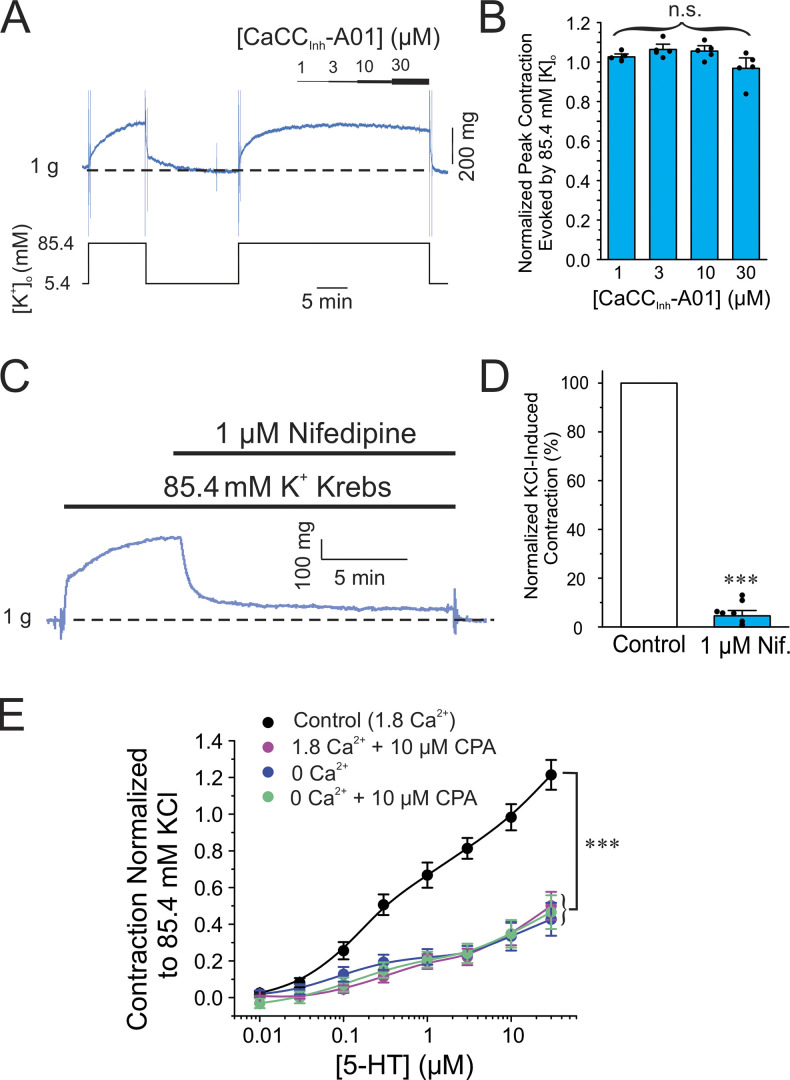

We first evaluated the contribution of ANO1, voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (VGCC), and Ca2+ release from the SR in the contraction elicited by the agonist 5-HT of endothelium-denuded wild-type C57/BL6 mouse pulmonary arteries using wire myography. Fig. 1 A shows two typical experiments in which a cumulative dose-response curve to 5-HT was generated in the absence (Fig. 1 A; Control) or presence of the ANO1 inhibitor CaCCInh-A01 (Fig. 1 A, right). For all experiments, only a single concentration–response relationship to 5-HT was generated in each preparation since pilot experiments revealed a significant attenuation of the response to a second 5-HT challenge, presumably due to receptor desensitization. The threshold concentration of 5-HT eliciting a measurable contraction in control condition was 30 nM (Fig. 1 A). CaCCInh-A01 (10 μM) significantly decreased peak contraction at all 5-HT concentrations tested and shifted the threshold concentration evoking a contraction to ∼300 nM (Fig. 1 A, right). The concentration of CaCCInh-A01 was chosen on the basis that it was previously shown to block ∼90% of expressed mouse ANO1 current in a voltage-independent manner (IC50 = 1.7 μM; Bradley et al., 2014), and caused no significant effect on the contraction to high K+ solution (85.4 mM; Fig. 2, A and B). The latter observation is important as it indicates that the compound exerted no direct effect on the contractile machinery, or VGCC, which contrasts with the potent inhibitory effect of the Ca2+ channel blocker nifedipine on this contraction (1 μM; Fig. 2, C and D). In the control condition, the concentration–response curve to 5-HT was biphasic (Fig. 1 B), an observation possibly attributable to the presence of 5-HT1B/1D and 5-HT2A receptor subtypes as identified in pulmonary arteries from several mammalian species including human, mouse, and rat (Uma et al., 1987; Cortijo et al., 1997; Shaw et al., 2000; Liu and Folz, 2004; Perez and Sanderson, 2005; Rodat-Despoix et al., 2009). The biphasic nature of the concentration–response relationship to 5-HT was still apparent following the block of ANO1 by CaCCInh-A01 (Fig. 1 B). Blocking VGCC with nifedipine, emptying SR Ca2+ stores with CPA (Seidler et al., 1989), or blocking the IP3R with xestospongin C (Gafni et al., 1997) produced very similar effects to those caused by the ANO1 inhibitor (Fig. 1 B), even though the curve obtained with nifedipine was slightly elevated relative to those of CaCCInh-A01, CPA, and xestospongin C, likely attributable to an incomplete block of VGCC with 1 μM nifedipine (Fig. 2, C and D). Remarkably, the concentration–response curve to 5-HT in the presence of CPA was also similar to preparations exposed to Ca2+-free solution or Ca2+-free in the presence of CPA (Fig. 2 E). These results suggest that activation of store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE) by CPA-induced store depletion in the presence of normal extracellular Ca2+ did not produce a significant contractile effect in our conditions. We least-square fitted individual dose-response relationships to 5-HT to a monophasic logistic function for all conditions. Only the initial component of the biphasic response was analyzed by restricting the fitting range from 0.01 to 1–3 μΜ 5-ΗT. This is because a maximum effect for the second component at higher concentrations of 5-HT was not clearly discernable. Table 1 summarizes mean data obtained for the estimated EC50, maximum contraction amplitude, and slope factor p, and provides a mean R2 for each condition. While there were no significant differences between each group and the control group for the EC50 and slope factor p, all treatments produced a significant inhibition of the maximum contraction amplitude, in accord with our two-way ANOVA analyses of these curves.

Figure 1.

Pharmacological block or genetic knockdown of ANO1 produces a similar inhibition of the contraction of mouse pulmonary artery to 5-HT as blocking VGCC or emptying Ca2+ stores from the SR. (A) Typical isometric force recordings in response to high K+ Krebs (85.4 mM) and increasing cumulative concentrations of 5-HT ranging from 0.01 to 30 μM as indicated by the bars above the traces, in the absence (left) or presence (right) of the ANO1 inhibitor CaCCInh-A01, also indicated by a horizontal bar above the trace. (B) Mean cumulative dose–response curves to 5-HT in mouse pulmonary arteries from wild-type C57/BL6 mice in the absence (black circles, Control; n = 14), or presence (blue squares; n = 5) of 1 μM nifedipine to block VGCC, 10 μM CPA to deplete SR Ca2+ stores (black diamonds; n = 4), 10 μM CaCCInh-A01 (magenta circles; n = 6) to block ANO1, or 1 μM xestospongin C to block IP3R (magenta triangles; n = 6). Each data point is a mean ± SEM of net contractile force normalized to the second high K+–Krebs solution-induced contraction (see examples in A and description in Materials and methods). (C) Mean cumulative dose–response curves to 5-HT in mouse pulmonary arteries from two conditional smooth muscle-specific and inducible ANO1 KO mice (SMC-ANO1-KO), one with floxed ANO1 flanking exons 5 and 6 (SMC-ANO1-KO-ΔEx5/6), and the other with floxed ANO1 flanking exon 12 (SMC-ANO1-KO-ΔEx12). The cumulative dose–response relationship to 5-HT in SMC-ANO1-KO-ΔEx12 injected with safflower oil served as a control (black squares; SMC-ANO1-KO-ΔEx12-Oil; n = 4) and displayed remarkable similarity to the control curve obtained with wild-type mice (B). SMC-ANO1-KO-ΔEx12 injected with tamoxifen (TMX) led to a significant reduction in contraction amplitude (upper magenta triangles; SMC-ANO1-KO-ΔEx12-TMX; n = 5), which was unaffected by exposure to 10 μM CaCCInh-A01 (black diamonds; n = 3). The magnitude of the contraction to 5-HT for tamoxifen-injected SMC-ANO1-KO-ΔEx5/6 mice was also reduced to a similar extent to that exerted by exon 12 deletion (inverted blue triangles; n = 5). (D) Reverse-transcription qPCR demonstrating ANO1 knockdown in aortic smooth muscle but not colonic tissue from both SMC-ANO1-KO mice used in this study (ANO1-KO-ΔEx5/6 and ANO1-KO-ΔEx12). Measurements were performed between 50 and 60 d after injection with safflower seed oil (light gray bars) or tamoxifen (open bars). ANO1 expression was normalized to β-actin. Each overlaid data point represents one animal; * and ***, significantly different from control with P < 0.05 and P < 0.001, respectively. (E) Ca2+-activated Cl− currents were abolished in PASMCs from SMC-ANO1-KO mice. Top: Typical families of Ca2+-activated Cl− currents (IClCa) recorded in PASMCs from SMC-ANO1-KO-ΔEx12 injected with vehicle (oil-injected; traces on the left) or tamoxifen (TMX-injected; traces on the right). Currents evoked with a pipette solution set to 1 μM Ca2+ were recorded in response to the voltage-clamp protocol shown below the traces. Bottom: Mean current–voltage relationships for IClCa measured at the end of voltage-clamp steps ranging from −100 to +120 mV from a holding potential of −50 mV in PASMCs from SMC-ANO1-KO-ΔEx12 mice injected with vehicle (SMC-ANO1-KO-Oil; filled circles) or tamoxifen (SMC-ANO1-KO-TMX; open circles). Each data point is a mean ± SEM SMC-ANO1-KO-Oil: N = 2, n = 5; SMC ANO1-KO-TMX: N = 4, n = 8; with N and n representing the number of animals and cells, respectively. For all panels, *** and * indicate a significant difference between means with P < 0.001 and P < 0.05, respectively.

Figure 2.

The ANO1 blocker CaCCInh-A01 produced no effect on the high K+-mediated contraction of the mouse pulmonary artery. (A) Typical contractile force experiment showing that increasing the concentration of CaCCInh-A01 from 1 to 30 μM (progressively thickening black bar shown over the trace) produced no noticeable effect on the contraction (blue trace) elicited by 85.4 mM K+–Krebs solution (K+ concentration changes are indicated with the black line below the contraction trace). (B) Mean bar graph summarizing the effects of different concentrations of CaCCInh-A01 on the contraction elicited by high K+–Krebs solution as in A. Contractile force at each concentration of CaCCInh-A01 was normalized to the net contraction elicited by high K+–Krebs solution obtained during the prior wash with this solution as shown on the left side of A. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM and data points overlaid on each bar represents individual animals (N = 5). (C) Typical contraction experiment showing the potent block produced by the CaV1.2 blocker nifedipine (Nif.; 1 μM; top black bar) on the contraction (blue trace) elicited by 85.4 mM K+–Krebs solution (bottom black bar). (D) Mean bar graph summarizing the effects of nifedipine on the contraction mediated by high K+–Krebs solution as in A. The mean net contractile force measured in the presence of nifedipine was normalized to that measured in the absence of the drug just prior to its addition (blue bar). The bar with nifedipine is a mean ± SEM. Overlaid data points represent different animals (N = 10). (E) Mean cumulative dose–response curves to 5-HT in mouse pulmonary arteries from wild-type C57/BL6 mice in the presence of normal extracellular Ca2+ concentration with (magenta circles; 1.8 Ca2+ + 10 μM CPA; N = 4) or without (black circles, Control [1.8 Ca2+]; N = 14) 10 μM CPA to deplete SR Ca2+ stores, or in Ca2+-free with (green circles; 0 Ca2+ + 10 μM CPA; N = 6) or without (blue circles; 0 Ca2+; N = 18) CPA. Each data point is mean ± SEM of net contractile force normalized to the second high K+–Krebs solution-induced contraction (see examples in A and description in Materials and methods). The control (1.8 Ca2+) and 1.8 Ca2+ + CPA curves were reproduced from Fig. 1 B. For all panels, *** indicates a significant difference between means with P < 0.001; n.s.: not significant.

Table 1.

Effects of various treatments on parameters calculated from dose–response relationships to 5-HT

| EC50 (nM) | Maximum 5-HT contraction amplitude (normalized to KCl) | Slope factor p | N | Mean R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | |||||

| Control | 209 ± 34 | 0.784 ± 0.073 | 1.57 ± 0.25 | 14 | 0.993 ± 0.004 |

| Nifedipine | 355 ± 117 | 0.451 ± 0.065* | 1.46 ± 0.33 | 5 | 0.997 ± 0.003 |

| CaCCInh-A01 | 673 ± 274 | 0.332 ± 0.059** | 1.33 ± 0.25 | 6 | 0.957 ± 0.019 |

| CPA | 309 ± 40 | 0.238 ± 0.045*** | 1.70 ± 0.44 | 4 | 0.996 ± 0.002 |

| Xestospongin C | 70 ± 10 | 0.294 ± 0.068*** | 1.93 ± 0.22 | 6 | 0.989 ± 0.003 |

| 0 Ca2+ | 211 ± 43 | 0.290 ± 0.060*** | 1.46 ± 0.30 | 11 | 0.986 ± 0.005 |

| 0 Ca2+ + CPA | 142 ± 19 | 0.306 ± 0.031*** | 1.12 ± 0.11 | 6 | 0.985 ± 0.011 |

Individual dose–response curves to 5-HT were least-square fitted to a logistic function of the following formalism: Y = A1 + [(A2 − A1)/(1 + ([5-HT]/EC50)p)], where Y is the contraction amplitude registered in the presence of 5-HT normalized to the high KCl-induced contraction, A1 and A2 are the minimum and maximum contraction amplitudes, respectively, [5-HT] is the concentration of 5-HT, EC50 is the concentration of 5-HT producing a contraction that is 50% of maximum, and p is the slope factor. Because of the biphasic nature of the dose–response curves to 5-HT (see Fig. 1 and text for explanation), only the initial portion of each curve, thus ranging from 0.01 to 1 or 3 μM 5-HT, was analyzed to calculate the parameters shown in the table. All values are means ± SEM pooled from 4 to 14 animals (N). One-way ANOVA tests revealed significant differences in the contraction amplitude between treatments and the control group (bolded numbers) with *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001. All other comparisons were not significant.

We repeated similar experiments in PA from two conditional smooth muscle-specific and inducible ANO1 KO mice, both driven by TMX-sensitive Cre expression under the control of the smooth muscle myosin heavy chain promoter located on the Y chromosome (My11). ANO1 knockdown induced by TMX is mediated by the deletion of loxP sequences flanking exons 5 and 6, or exon 12. Both animal models also conditionally express the Ca2+ biosensor protein GCaMP3 under the control of the same Cre-lox system (SMC-ANO1-kO-ΔEx5-6-GCaMP3 and SMC-ANO1-kO-ΔEx12-GCaMP3). The cumulative concentration-response curve to 5-HT of PA from SMC-ANO1-kO-ΔEx12-GCaMP3 animals injected with vehicle (oil; Fig. 1 C) was nearly superimposable to that obtained from wild-type mice (Fig. 1 B), displaying a similar threshold around 30 nM, a biphasic relationship and a similar peak contraction at the highest concentration of 5-HT. ANO1 knockdown resulted in a significantly reduced concentration–response curve to 5-HT that mimicked that obtained in PA from wild-type mice exposed to CaCCInh-A01, nifedipine, CPA, or xestospongin C (Fig. 1 B). A very similar profile was registered in PA from SMC-ANO1-kO-ΔEx5,6-GCaMP3 mice (Fig. 1 C). We also fitted these relationships using the same approach as that described in Table 1. As for the effects of various inhibitory conditions on PA from wild-type mice, a decrease in maximal contraction amplitude was the only parameter that was significantly affected and reduced by ANO1 knockdown (Table 2). Notably and importantly, the EC50 and maximum contraction amplitude estimated for wild-type and oil-injected SMC-ANO1-kO-ΔEx12-GCaMP3 mice were remarkably similar with an EC50 of ∼210 nM and maximum contraction amplitude of ∼0.8 (normalized to KCl).

Table 2.

Parametric comparisons of dose–response relationships to 5-HT generated in wild-type and conditional smooth muscle–specific ANO1 KO mice

| EC50 (nM) | Maximum 5-HT contraction amplitude (normalized to KCl) | Slope factor p | N | Mean R 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | |||||

| Control | 209 ± 34 | 0.784 ± 0.073 | 1.57 ± 0.25 | 14 | 0.993 ± 0.004 |

| ANO1-KO Δ exon 12 | |||||

| Oil-injected control | 210 ± 36 | 0.771 ± 0.105 | 1.14 ± 0.17 | 4 | 0.993 ± 0.002 |

| TMX-injected | 125 ± 24 | 0.250 ± 0.034 a , b | 1.54 ± 0.31 | 5 | 0.981 ± 0.008 |

| ANO1-KO Δ exons 5/6 | |||||

| TMX-injected | 195 ± 72 | 0.316 ± 0.056 a , c | 0.96 ± 0.15 | 5 | 0.924 ± 0.062 |

Individual dose–response curves to 5-HT were least-square fitted to a logistic function of the following formalism: Y = A1 + [(A2 − A1)/(1 + ([5-HT]/EC50)p)], where Y is the contraction amplitude registered in the presence of 5-HT normalized to the high KCl-induced contraction, A1 and A2 are the minimum and maximum contraction amplitudes, respectively, [5-HT] is the concentration of 5-HT, EC50 is the concentration of 5-HT producing a contraction that is 50% of maximum, and p is the slope factor. Because of the biphasic nature of the dose–response curves to 5-HT (see Fig. 1 and text for explanation), only the initial portion of each curve, thus ranging from 0.01 to 3 μM 5-HT, was analyzed to calculate the parameters shown in the table. All values are means ± SEM pooled from 4 to 14 animals (N). One-way ANOVA tests revealed significant differences in the maximum contraction amplitude between animal groups as shown (bolded numbers).

P < 0.01 versus wild-type control.

P < 0.01 versus ANO1-KO Δ exon 12.

P < 0.05 versus ANO1-KO Δ exon 12.

Real-time quantitative PCR experiments revealed a marked reduction in the expression of ANO1 mRNA in the aorta of both animal models (>75%), but not in the colon (Fig. 1 D). This is consistent with ANO1 in the colon being expressed almost exclusively in c-Kit+ interstitial cells of Cajal where they play a major role in driving pacemaker activity and initiating slow waves, but not in smooth muscle cells in this tissue (Huang et al., 2009; Hwang et al., 2009; Zhu et al., 2009; Berg et al., 2012; Sanders et al., 2012). Consistent with a reduced expression of ANO1 protein, Ca2+-activated Cl− currents in PASMCs from SMC-ANO1-kO-ΔEx12-GCaMP3 mice treated with TMX were abolished (Fig. 1 E). Finally, CaCCInh-A01 exerted no additional effects on the PA contraction of SMC-ANO1-kO-ΔEx12-GCaMP3 (Fig. 1 C). These results indicate that a high level of knockdown of ANO1 protein was achieved in PASMCs in both transgenic mouse models injected with TMX. They also suggest that the inhibitory effects of CaCCInh-A01 in PA from wild-type mice specifically targeted ANO1.

ANO1 is key for maintaining 5-HT-mediated Ca2+ signaling

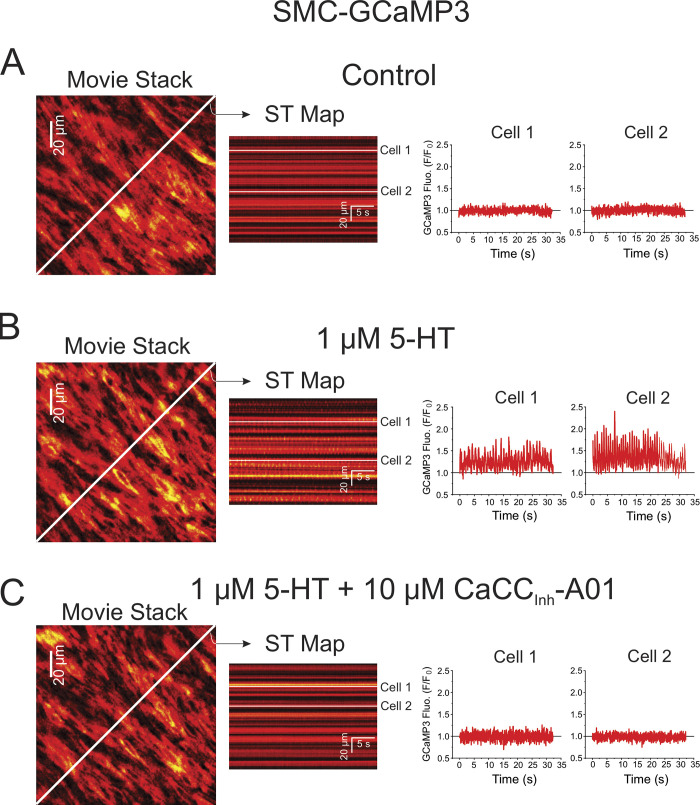

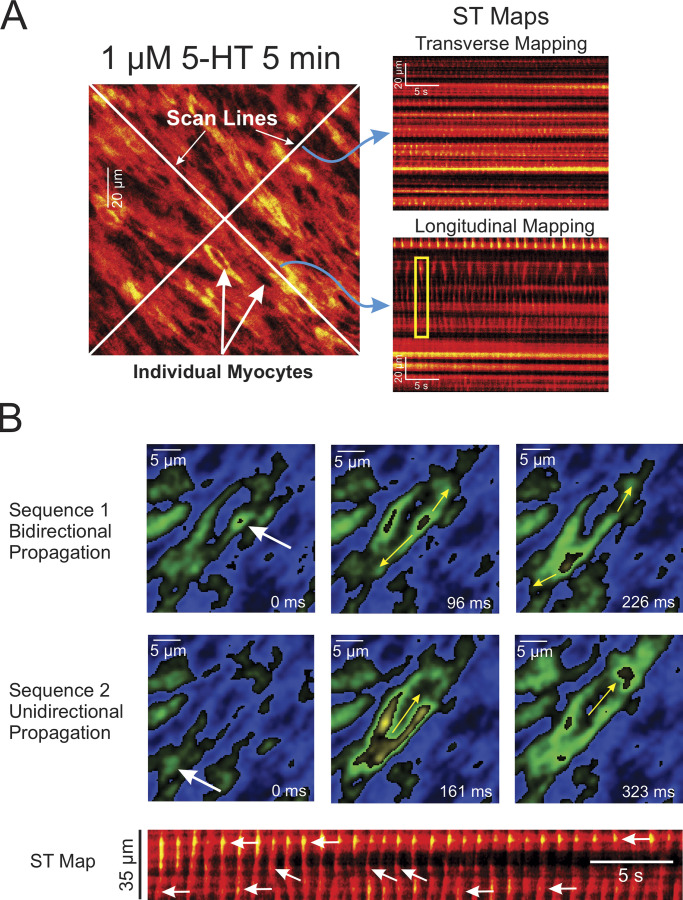

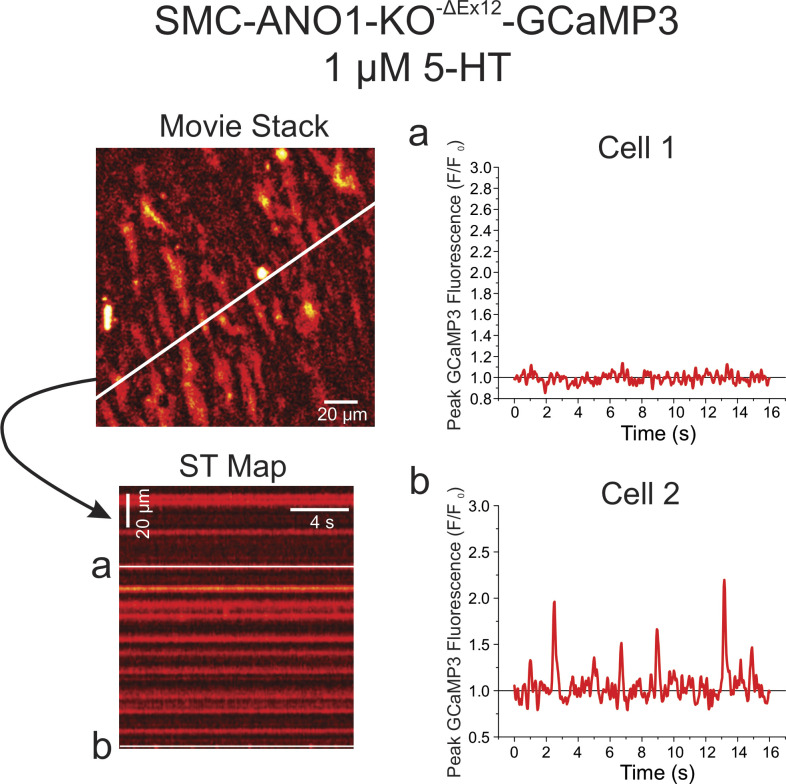

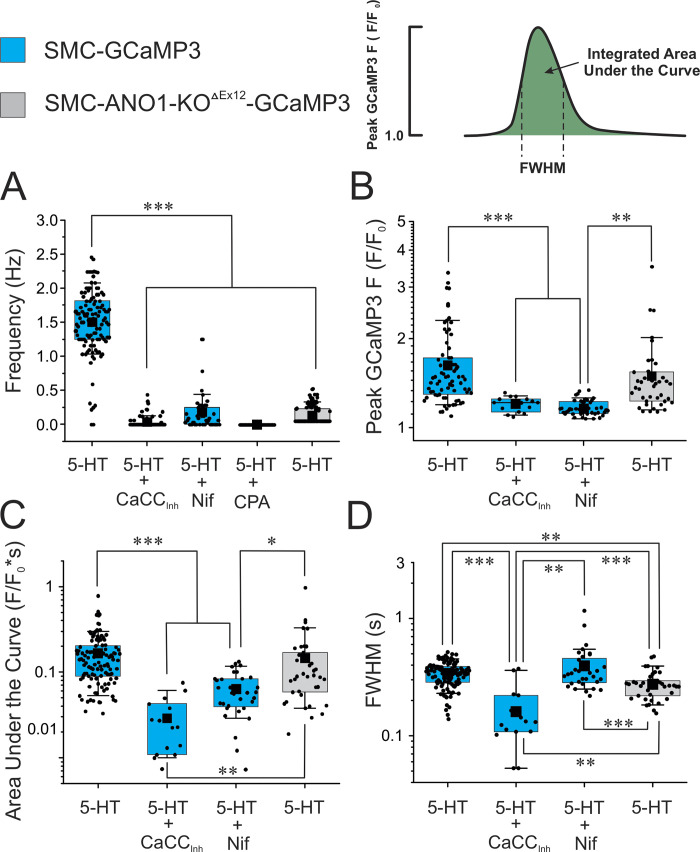

We used fluorescence imaging to explore the mechanisms involved in the effects of 5-HT on changes in intracellular Ca2+ concentration in intact endothelium-denuded PA from transgenic mice conditionally expressing the Ca2+ reporter GCaMP3, specifically in smooth muscle cells. Spontaneous Ca2+ transients were detected in some preparations in the absence of 5-HT, but these were extremely rare events and were therefore not analyzed (Fig. 3 A and Video 1). Exposure to 1 μM 5-HT elicited asynchronous Ca2+ oscillations at a frequency of ∼1.5 Hz (Fig. 3 B and Video 2). Ca2+ transients analyzed by creating ST maps along the longitudinal axis of the smooth muscle cells revealed that Ca2+ transients propagated as waves within the cell but did not spread from cell to cell (Fig. 4 A). Lack of or poor cell-to-cell propagation of these Ca2+ transients was also evident when analyzed orthogonally from the long axis of the cells (Fig. 4 A). These results are in agreement with the concept that each cell generates its own Ca2+ oscillations producing sustained force integrated over time by the frequency and amplitude of Ca2+ transients (Perez-Zoghbi and Sanderson, 2007). Although not analyzed in detail, Ca2+ transients were generally initiated from a few regions or “hot spots” in the cell. An example is shown in Fig. 4 B, where Ca2+ waves were randomly triggered from either end of the cell and propagated unidirectionally, or an area near the nucleus that propagated bidirectionally toward the cell ends. Video 3 highlights these properties. 5-HT-induced Ca2+ transients were nearly abolished by CaCCInh-A01 in PA from SMC-GCaMP3 mice (Fig. 3 C and Video 4) and potently inhibited by genetic knockdown of ANO1 (SMC-ANO1-kO-ΔEx12-GCaMP3; Fig. 5). We systematically analyzed several parameters of Ca2+ transients recorded in different conditions and preparations. Fig. 6 shows that blocking ANO1 with CaCCInh-A01 or blocking VGCC with nifedipine in PA from SMC-GCaMP3 mice (Control; light blue bars) led to a quantitatively similar reduction in frequency (Fig. 6 A), peak Ca2+ transient amplitude (Fig. 6 B), and integrated area under the curve (Fig. 6 C); the duration of Ca2+ transients measured at half-amplitude was significantly reduced by CaCCInh-A01, but not by nifedipine (Fig. 6 D). Depleting Ca2+ stores with CPA abolished Ca2+ oscillations (Fig. 6 A). Importantly, genetic deletion of ANO1 in SMC-ANO1-kO-ΔEx12-GCaMP3 mice (light gray bars) produced a reduction in the frequency and duration of Ca2+ transients (Fig. 6, A and D) relative to control, but did not significantly alter peak amplitude and integrated area under the curve (Fig. 6, B and C). Taken together, these results suggest that the Ca2+ oscillations evoked by 5-HT are supported by the coordinated stimulation of ANO1, Ca2+ entry through VGCC (CaV1.2), and Ca2+ release from the SR, most likely from IP3R.

Figure 3.

Ca2+ oscillations triggered by 5-HT in individual smooth muscle cells from an intact mouse endothelium-denuded PA are potently inhibited by the inhibition of ANO1. All data were collected from the same PA from a conditional smooth muscle–specific and inducible GCaMP3 mouse injected with tamoxifen to induce Cre expression. (A) Ca2+ imaging was performed in the absence of an agonist (Control). The left panel shows one image from a video from which a ST map (middle colored image) was created in the area spanned by the diagonal white line. Fluorescence intensity was measured under the three white lines on the ST map (corresponding to two different cells) and plotted as a function of time as shown on the right. There was no detectable activity in these two cells as well as across the entire field of view of the movie. (B) Same nomenclature as in A except that the preparation was exposed to 1 μM 5-HT for 5 min. A ST map created in the same manner as that in A shows clear evidence of asynchronous Ca2+ transients. This is more evident from examining the fluorescence intensity profile of the same two cells analyzed in A, which displayed repetitive Ca2+ transient of distinct magnitude and frequency. (C) The nomenclature of this panel is identical to that of B and C, with the exception that the PA was exposed to 10 μM CaCCInh-A01 for 10 min while still being incubated with 5-HT. Examination of the ST map reveals little, if any, Ca2+ oscillations in the presence of the ANO1 inhibitor; Ca2+ transients were no longer apparent in the same two cells analyzed in A and B.

Figure 4.

Examples of asynchronous Ca2+ oscillations and waves in PASMCs from intact PAs from SMC-GCaMP3 mice. (A) Examples of ST maps created by analyzing a video recorded from an intact endothelium-denuded PA from a SMC-GCaMP3 mouse exposed to 1 μM 5-HT for 5 min. The left larger image was extracted from a video stack onto which were drawn two white scan lines. The scan lines were oriented along or orthogonally to the main axis of the cells. The two images on the right show ST maps that were created by reporting fluorescence intensity registered under the scan line drawn orthogonally (Transverse Mapping) or along (Longitudinal Mapping) the main axis of the cells, respectively. The top ST map clearly shows a lack of cell-to-cell propagation of Ca2+ transients (bright luminous spots) in the transverse direction. Longitudinal mapping also suggests a lack of or poor evidence for propagation from one cell to the next along the main axis of the cells. Ca2+ transients propagated along the main axis of the cells (as evidenced from the near vertical streaks of fluorescence) but collapsed at the end of the cells, failing to propagate the signal to neighboring cells (one example highlighted by the yellow box). (B) Two series of images showing the initiation and propagation of two Ca2+ waves (top and bottom sets of images) taken at different times from the original movie. The white arrows show trigger sites. The yellow arrows illustrate the direction of propagation of the waves. The ST map at the bottom of the panel was reconstructed from the entire video with time passing from left to right. The white arrows indicate the location of at least three trigger sites that initiated Ca2+ waves in this particular cell. The trigger sites randomly changed from either of the cell tips or the middle of the cell. Bidirectional propagation from the middle site is evident from the “V” shape appearance of these particular waves.

Figure 5.

Sample experiment illustrating how ANO1 knockdown exerted a strong inhibition of 5-HT-induced Ca2+ oscillations in a PA from a tamoxifen-injected SMC-ANO1-KO-ΔEx12-GCaMP3 mouse. The top left panel is an image from a video stack recorded in a pulmonary artery from a conditional smooth muscle cell-specific and inducible ANO1 knockout mouse expressing GCaMP3 specifically in smooth muscle cells, which was exposed to 1 μM 5-HT for 5 min. One ST map constructed from the white line crossing the image is shown in the lower left corner and reveals very little activity. The fluorescence intensity profile as a function of time of two cells from the ST map labeled with the letters a and b are shown on the right. Cell 1 displayed no significant Ca2+ activity while Cell 2 showed low-frequency Ca2+ events.

Figure 6.

Asynchronous Ca2+ oscillations evoked by 5-HT require both functional ANO1 and VGCC. Mean data for each of four parameters measured from Ca2+ transients elicited by 1 μM 5-HT (5 min) in PA from control SMC-GCaMP3 (light blue bars) or SMC-ANO1-KO-ΔEx12-GCaMP3 (light gray bars) mice. (A–D) The frequency of Ca2+ oscillations (A), peak Ca2+ transient amplitude (F/F0; B), integrated area under the curve (C), and FWHM (D) were measured as shown in the upper right corner. For each dataset, the mean is indicated by a filled black square with the colored boxes and whiskers delimiting the 25th and 75th percentile, and the 10th and 90th percentile of the pooled data, respectively, and small dots individual data points. N: number of animals; n: number of cells. SMC-GCaMP3 + 5-HT: N = 7, n = 114 for peak, area under the curve, and FWHM, and n = 116 for frequency; SMC-GCaMP3 + 5-HT + CaCCInh-A01 (CaCCInh): N = 7, n = 15 for peak, area under the curve, and FWHM, and n = 76 for frequency; SMC-GCaMP3 + 5-HT + nifedipine (Nif): N = 2, n = 32 for peak, area under the curve, and FWHM, and n = 47 for frequency; GCaMP3 + 5-HT + CPA: N = 2, n = 29; SMC-ANO1-KO-ΔEx12-GCaMP3; 5-HT: N = 7, n = 39 for peak, area under the curve, and FWHM, and n = 137 for frequency. For all panels, ***, **, and * indicate a significant difference between means with P < 0.001, P < 0.01, and P < 0.05, respectively.

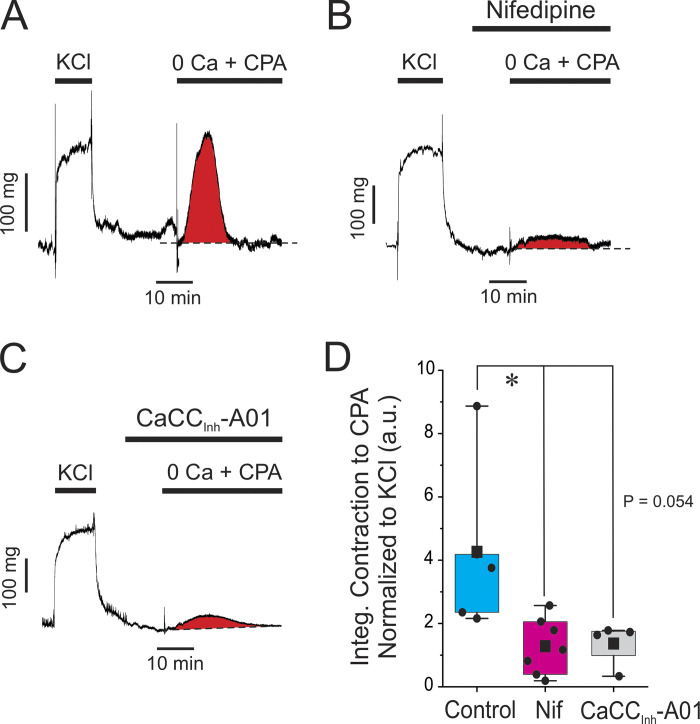

ANO1 and CaV1.2 are critical for refilling SR Ca2+ stores

The results presented so far suggest that Ca2+ release from IP3R is the predominant Ca2+ source generating Ca2+ oscillations and contractility in response to 5-HT, and the feedback loop between ANO1 and CaV1.2 may be key for reloading SR Ca2+ stores. We tested this hypothesis by examining the effects of blocking ANO1 or CaV1.2 on the amount of Ca2+ stored in the SR. This was indirectly assessed by measuring the transient contraction produced by blocking the SR Ca2+-ATPase with 10 μM CPA in the absence of external Ca2+. Fig. 7 A shows an isometric force recording illustrating the impact of switching the external solution from normal Krebs containing 1.8 mM Ca2+ to the Ca2+-free/CPA solution. As highlighted by the red area under the trace, the latter solution produced a robust transient contraction that was evoked by Ca2+ mobilization from the SR. In contrast, a 10-min exposure to 1 μM nifedipine or 10 μM CaCCInh-A01 to block CaV1.2 (Fig. 7 B) or ANO1 (Fig. 7 C), respectively, markedly inhibited this contraction. We quantified the effects of the two inhibitors by integrating the area under the curve for the transient contraction (highlighted in red in A–C) and normalizing it to the amplitude of contraction caused by the high K+–Krebs solution that preceded the 0 Ca2+/CPA protocol (contraction to high KCl shown on the left side of A–C). Fig. 7 D indicates that CaCCInh-A01 and nifedipine produced a strong inhibition of the contraction elicited by 0 Ca2+/CPA; there was no significant difference between the two drug treatments. These experiments support the concept that the main function of ANO1 and CaV1.2 is to refill Ca2+ stores in the SR to support cyclical Ca2+ release through IP3R.

Figure 7.

Blocking ANO1 or CaV1.2 depletes SR Ca2+ stores. (A) Typical isometric force recording obtained under control conditions showing the effect of depleting the SR Ca2+ stores. After eliciting a sustained contraction with high K+ (KCl; 85.4 mM), the preparation was switched to normal Krebs for 20 min, which relaxed the artery to baseline. The solution was subsequently changed to a Ca2+-free Krebs solution containing 100 μM EGTA and 10 μM cyclopiazonic acid (0 Ca + CPA), which triggered a transient contraction produced by releasing Ca2+ from internal SR Ca2+ stores. The area under the curve for the transient contraction highlighted in red was measured and used as an index of the amount of Ca2+ stored in the SR. (B and C) Similar experiments to that shown in A, with the exception that each preparation was incubated for 10 min with 1 μM nifedipine or 10 μM CaCCInh-A01, respectively, prior to switching to the Ca2+-free solution with CPA in the presence of either drug. Both compounds exerted a strong inhibition of the transient contraction elicited by CPA as evident from the much reduced area under the curve shown in red. (D) Pooled data from similar experiments are shown in A–C. For each dataset, the mean is indicated by a filled black square with the colored boxes and whiskers delimiting the 25th and 75th percentile, and the 10th and 90th percentile of the pooled data, respectively, and small dots individual data points of the integrated contraction measured in the presence of 0 Ca + CPA, normalized to the KCl-induced contraction (a.u.: arbitrary unit). Control, N = 5; nifedipine, N = 7; CaCCInh-A01, N = 4; * indicates a significant difference between means with P < 0.05. The comparison between the Control and CaCCInh-A01 groups was just at the limit of significance as shown.

ANO1, CaV1.2, and cortical IP3R form functional coupling sites at SR/PM junctional microdomains for efficient Ca2+ signaling in mouse PASMCs

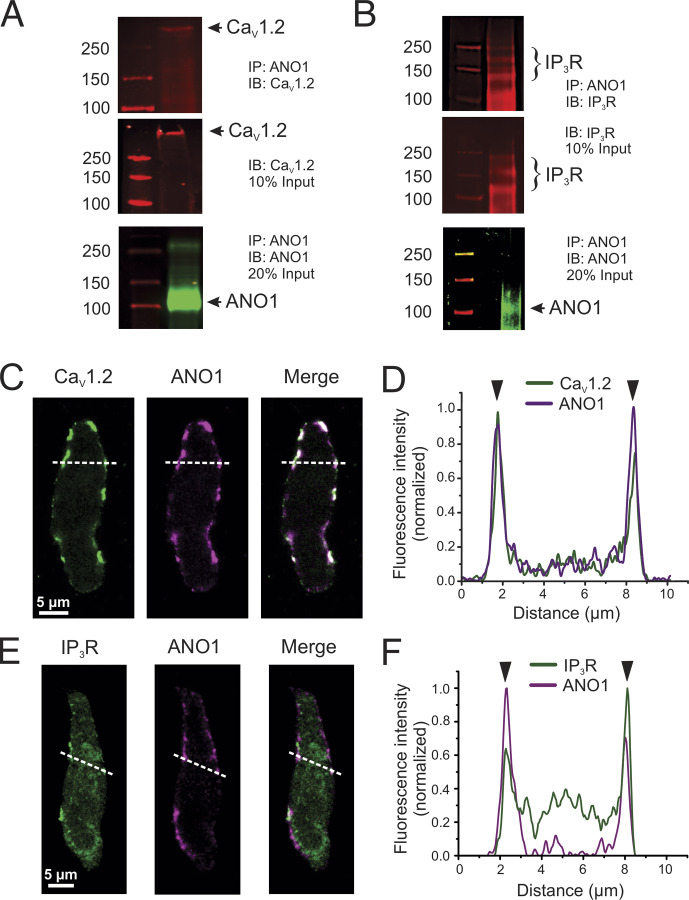

The combination of the functional observations described above with the very low number of detectable sites in each cell found to initiate Ca2+ waves led us to hypothesize that ANO1 and CaV1.2 in the PM and IP3R in closely juxtaposed SR contact areas may be clustered in a limited number of specialized microdomains along the cell length to form a specialized unit optimized for EC coupling of PASMCs. To test this hypothesis, we performed co-IP assays complemented by colocalization studies by confocal and superresolution nanomicroscopy.

Co-IP studies

Immunoprecipitation of ANO1 from freshly prepared total lysates of mouse PA followed by probing with CaV1.2 and IP3R antibodies, respectively, detected a high molecular weight band consistent with CaV1.2 (>250 kD) and several bands ≥100 kD for IP3R (∼240, 180, and 120 kD) in the immunoprecipitated macromolecular complex (Fig. 8, A and B). Of the three IP3 bands, the higher one appears the most likely candidate for IP3R as all three isoforms have a molecular weight >200 kD (Monkawa et al., 1995). Input from total PA lysate (10%) detected the same immunoreactive bands for CaV1.2 and IP3R. A band near the size predicted (∼110 kD) for ANO1 monomeric protein was also detected from the immunoprecipitated complex, which could not be achieved when total lysates were directly probed by Western blot with the same ANO1 antibody, most likely attributable to the low abundance of ANO1 protein in PA tissue (data not shown). These results support the notion that cortical IP3R and CaV1.2 reside in the same membrane fraction as ANO1.

Figure 8.

ANO1, CaV1.2, and IP3R colocalize in peripheral coupling sites to form signaling complexes. (A and B) Co-IP of CaV1.2 or IP3R with ANO1 from lysates of the pulmonary artery from wild-type mice. Pulldown was carried out with anti-ANO1 antibody and then probed by Western blot with anti-CaV1.2, anti-IP3R, or anti-ANO1 antibodies. Five to six mouse tissues per experiment, each ran in triplicates. (C and D) Freshly isolated PASMCs from wild-type mice were immunolabeled for ANO1 and CaV1.2 (C) or ANO1 and IP3R (D). All three proteins were preferentially localized to the periphery of the cells. (D and F) Line profiles of the areas indicated by the white dashed lines in C and E. The fluorescence intensity was normalized to the minimum and maximum fluorescence for each sample. The black arrowheads denote the location of the PM. ANO1 and CaV1.2 show strong immunolabeling at the PM (D). (E) IP3R shows some intracellular immunolabeling, with moderate peaks present at the periphery showing an enhancement of protein localization to peripheral coupling sites. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F8.

Peripheral distribution of ANO1, CaV1.2, and IP3R in PASMCs

Laser scanning confocal fluorescence microscopy was first used to visualize mouse PASMCs dually immunolabeled for ANO1 and CaV1.2, or ANO1 and IP3R. Both protein pairs demonstrated a preferential colocalization near the PM of PASMCs although significant immunolabeling of IP3R was also apparent in the cytosol as expected for a protein expressed in the SR (Fig. 8, C and E). Line plots of normalized fluorescence intensity of regions indicated by the dashed white lines in Fig. 8, D and F, show an excellent correlation of fluorescence intensity near the PM between ANO1 and CaV1.2 (Fig. 8 D), and between ANO1 and IP3R (Fig. 8 F), albeit significant labeling for IP3R was apparent intracellularly as expected.

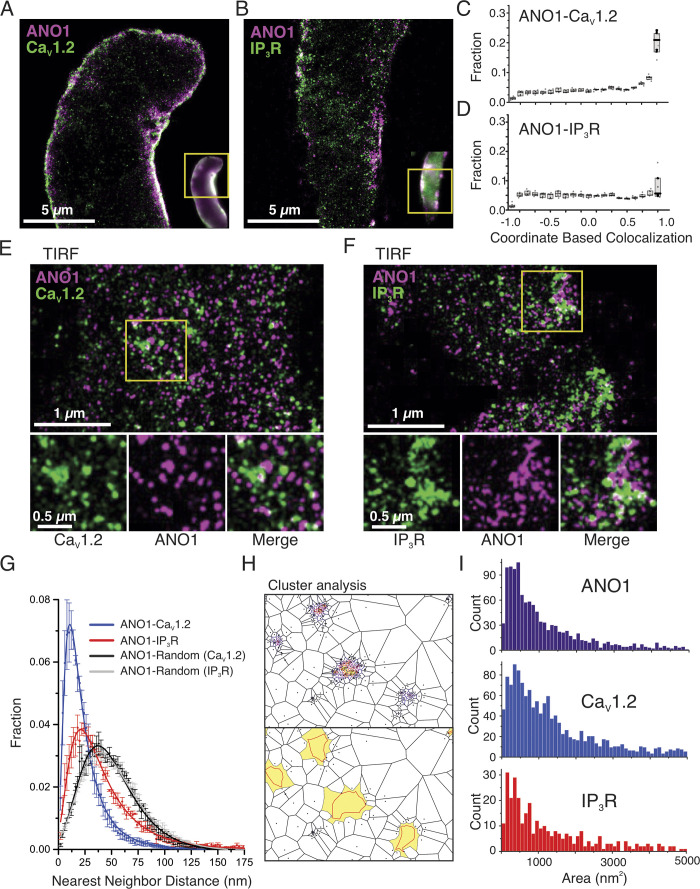

Nanoscale colocalization of ANO1 with CaV1.2 and IP3R in PASMCs

We further investigated the colocalization of ANO1 with CaV1.2 and IP3R protein clusters at nanoscale resolution (<40 nm) using GSDIM (ground-state depletion followed by individual molecule return)superresolution microscopy. Mouse PASMCs were dually immunolabeled in pairs either with ANO1 versus CaV1.2 or ANO1 versus IP3R and imaged in either epifluorescence illumination mode or TIRF mode using GSDIM. Superresolution images were created using the ImageJ plugin ThunderSTORM. In the epifluorescence mode of acquisition, molecules could be visualized close to the periphery (Fig. 9, A and B), especially for the ANO1-CaV1.2 pairing. We used the ThunderSTORM coordinate-based colocalization (CBC) algorithm to quantify the spatial correlation of the proteins where the single-molecule localizations (SML) for each protein pair are given a value of −1 to 1, where −1 is anticorrelated, 0 suggests a random distribution with respect to each other, and 1 is highly correlated. We found that the highest percentage of localizations for ANO1-CaV1.2 in epifluorescence mode were within the range of 0.9–1, demonstrating a high degree of correlation (Fig. 9 C). The CBC value for IP3R was not as high albeit significant due to the presence of intracellular IP3R proteins (Fig. 9 D), which would be expected for a protein localized to the SR. We next imaged the protein pairs using TIRF mode, allowing us to determine the distance between the protein pairs at the periphery of the cell with high resolution. We determined the nearest neighbor distance for each protein pair based on the single-molecule distributions of localizations for each protein. Here, we found that both CaV1.2 and IP3R are located closer to ANO1 than randomly localized particles (Fig. 9 G).

Figure 9.

Superresolution imaging of ANO1, CaV1.2, and IP3R at the PM of PASMCs from wild-type mice. (A and B) Superresolution images of PASMCs labeled for ANO1 and CaV1.2 (A) or ANO1 and IP3R (B) were imaged using GSDIM in epifluorescence mode. Epifluorescence images are shown in the inset for reference, with the yellow box demonstrating the region for GSD imaging. (C and D) Coordinate-based colocalization (CBC) of ANO1-CaV1.2 (C) or ANO1 and IP3R (D) where −1 shows mutual exclusion and +1 shows high correlation. (E and F) Superresolution images of PASMCs labeled with ANO1 and CaV1.2 (E) or ANO1 and IP3R (F) were imaged using GSDIM in TIRF mode. Enlargements of the white boxes are shown to the right, highlighting the adjacent location of the protein pairs. (G) Nearest neighbor analysis of the protein pairs demonstrates that the single-molecule localizations of CaV1.2 (blue) and IP3R (red) are both located closer to ANO1 than would be expected for a randomly distributed protein (black and grey). (H) An example of Voronoï-based segmentation of CaV1.2 single-molecule localizations (top) and the corresponding identified clusters are shown in yellow with the outline of the identified clusters denoted by the red line (bottom). (I) Cluster sizes of ANO1 (top), CaV1.2 (middle), and IP3R (bottom) as determined using SR-Tesseler analysis as shown in H.

Analysis of the size and density of clusters

Using the program SR-Tesseler approach (Levet et al., 2015), we investigated the clustering of the molecules on or near the PM. The localization data from the TIRF-based SMLs were subdivided using Voronoï tessellation (or segmentation), which creates polygonal regions around each point that is equidistant from surrounding localizations, as demonstrated in Fig. 9 H, top panel. Parameters such as area, density, and mean distance to the surrounding polygons are used to determine areas of higher molecular densities. Using this method, we measured the size of clusters that had a density 2.5 times greater than the average molecule density. Examples of identified clusters are shown in Fig. 9 H, bottom panel, with the polygons that were included in the cluster identified in yellow, and the shape of the identified clusters are shown by the red line. All three protein cluster sizes similarly ranged from <50 to >5,000 nm2, with the majority of clusters ranging from 100 to 500 nm2 (Fig. 9 I). Taken together, these results indicate that ANO1 and CaV1.2, and ANO1 and IP3R, colocalize in microdomains of similar sizes in specific areas near the PM of PASMCs, which may be optimally organized for effective agonist-mediated Ca2+ signaling.

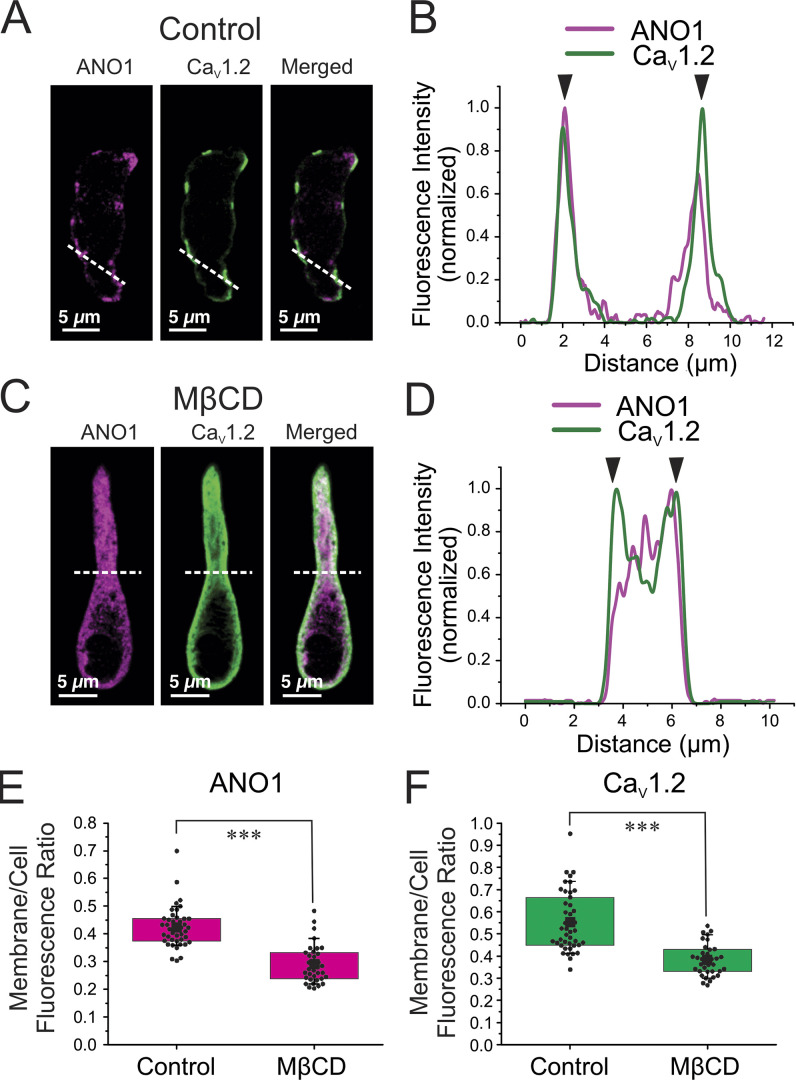

Disruption of lipid rafts eliminates PM ion channel super clusters and inhibits 5-HT-mediated EC-coupling

The results presented above suggest that unique coupling sites at the PM of PASMCs are important for Gq-protein receptor-mediated EC coupling. We hypothesized that these structural microdomains may be intimately associated with lipid rafts, and perhaps with caveolae, a subset of lipid rafts, which are known to be involved in sequestering membrane receptors and ion channels for optimal compartmentalized signal transduction (Patel et al., 2008; Thomas and Smart, 2008; Guéguinou et al., 2015). This is also based on previous reports showing that both ANO1 and CaV1.2 are localized in caveolae (Jorgensen et al., 1989; Darby et al., 2000; Löhn et al., 2000; Sones et al., 2010). Fig. 10, A–D shows the effect of incubating wild-type PASMCs for 30 min with 3 mg/ml methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD) on the cellular distribution of ANO1 and CaV1.2. MβCD causes membrane cholesterol depletion, which disrupts lipid rafts and caveolae (Rodal et al., 1999; Zidovetzki and Levitan, 2007; Patel et al., 2008). The PASMCs shown in Fig. 10, A and C, were isolated from the same animal. Similar to the results presented in Fig. 6, ANO1 and CaV1.2 displayed strong PM colocalization (Fig. 10, A and B) as probed by confocal microscopy. As anticipated, exposure to MβCD resulted in the disappearance of the ANO1/CaV1.2 superclusters and caused significant internalization of both proteins (Fig. 10, C and D). We quantified in PASMCs from three mice the redistribution of ANO1 and CaV1.2 by measuring the ratio of the membrane to total cell fluorescence. MβCD caused a 31.5% and 31.0% reduction in this parameter for ANO1 (Fig. 10 E) and CaV1.2 (Fig. 10 F), respectively, indicating that membrane cholesterol depletion produced a quantitatively similar effect on both proteins.

Figure 10.

Membrane cholesterol depletion with MβCD causes the internalization of ANO1 and CaV1.2 proteins. (A and C) Freshly isolated PASMCs from wild-type mice were immunolabeled for ANO1 and CaV1.2 before (A) or after (C) a 30-min exposure to MβCD (3 mg/ml; MβCD) to deplete membrane cholesterol and disrupt lipid rafts. The two ion channel proteins were preferentially localized to the periphery of the cells in control conditions as similarly shown in Fig. 8. (B–D) Line profiles of the areas indicated by the white dashed lines in A and C are respectively displayed in B and D. For these plots, the fluorescence intensity was normalized to the minimum and maximum fluorescence for each sample. The black arrowheads denote the location of the PM. ANO1 and CaV1.2 show strong immunolabeling at the PM in control condition (C) and translocation toward the center core of the cell after exposure to MβCD (D). The cells from A and C were isolated from the same mouse. (E and F) Graphs summarizing the effects of exposing PASMCs to MβCD on the distribution of ANO1 (magenta bars) and CaV1.2 (green bars), respectively. Measurements were performed as described in the text and consisted in normalizing membrane fluorescence to total cell fluorescence. For each dataset, the mean is indicated by a large, filled black square with the colored boxes and whiskers delimiting the 25th and 75th percentile, and the 10th and 90th percentile of the pooled data, respectively, and small dots individual data points. N: number of animals; n: number of cells; for the control group (E): ANO1 and CaV1.2: N = 3, n = 43; for the MβCD group (F): ANO1 and CaV1.2: N = 3, n = 35. *** indicates a significant difference between means with P < 0.001.

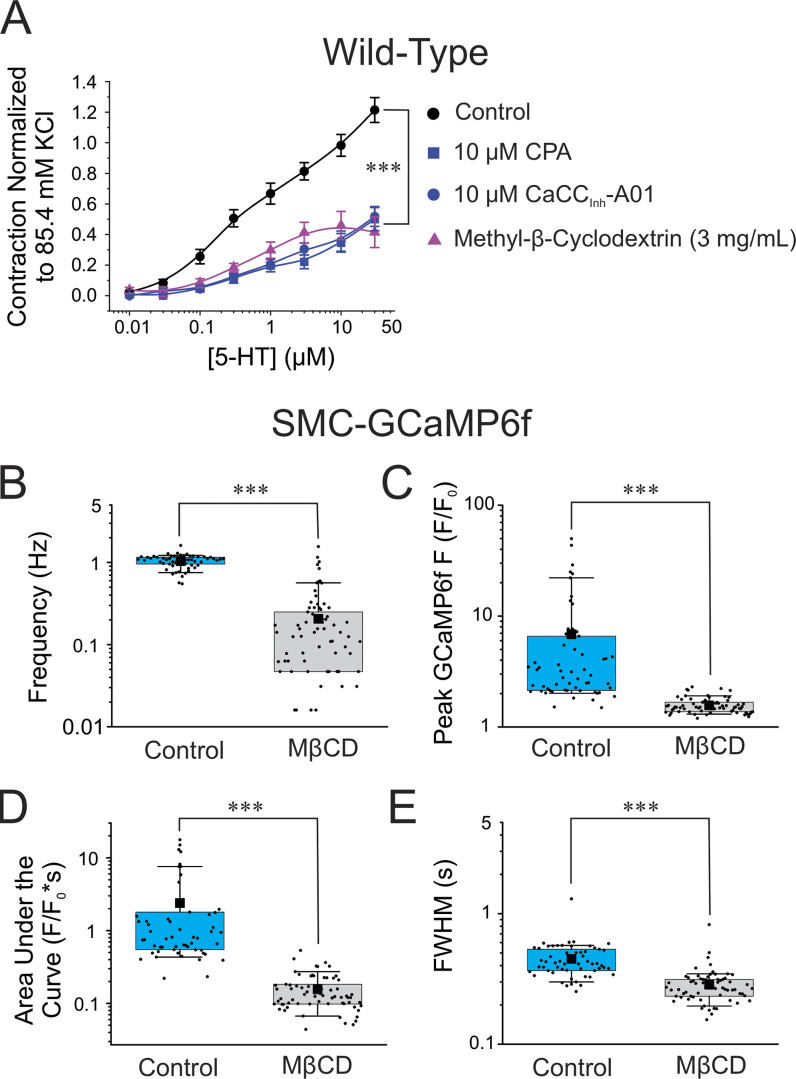

We next examined the functional significance of disrupting lipid rafts on 5-HT receptor-mediated signaling in intact PA. Exposing arteries to MβCD caused a similar decrease in the contraction to 5-HT as that produced by either CaCCInh-A01 or CPA (both datasets reproduced from Fig. 1 A). In contrast, the contraction amplitude triggered by high K+ (85.4 mM) was not significantly different between control and MβCD-treated arteries (data not shown; Control: 0.25 ± 0.04 g, n = 10; MβCD: 0.27 ± 0.03 g, n = 5; P > 0.05). These results indicate that the reduction of the 5-HT-induced contraction caused by MβCD was not due to an inability of intact PA to contract to a depolarizing stimulus. We next investigated how the same treatment would influence Ca2+ signaling evoked by 5-HT in intact PA from SMC-GCaMP6f mice. Consistent with the contraction data, MβCD (3 mg/ml for 30 min) significantly reduced the frequency (Fig. 11 B), amplitude (Fig. 11 C), the area under the curve (Fig. 11 D), and duration (Fig. 11 E) of GCaMP6f Ca2+ transients. These results indicate that the destruction of ANO1 and CaV1.2 coupling sites on the PM by MβCD had a major disrupting impact on the ability of 5-HT to trigger Ca2+ oscillations and force production.

Figure 11.

Disruption of lipid rafts with MβCD inhibits EC coupling mediated by 5-HT. (A) Mean cumulative dose–response curves to 5-HT in mouse pulmonary arteries from wild-type C57/BL6 mice in control condition (black circles, Control; N = 14), a 10-min exposure to 10 μM CPA (blue squares; N = 4), a 10-min exposure to 10 μM CaCCInh-A01 (blue circles; N = 6), or after a 30-min incubation with MβCD (3 mg/ml) to deplete membrane cholesterol and disrupt lipid rafts (upper triangles; N = 5). The data for the control, CPA, and CaCCInh-A01 groups were reproduced from Fig. 1 B to facilitate comparisons. Each data point is a mean ± SEM of net contractile force normalized to the second high K+–Krebs solution-induced contraction (see description in Materials and methods). (B–E) The summarized data presented in B–E show the effects of exposure of pulmonary arteries from conditional and smooth muscle-specific GCaMP6f mice (SMC-GCaMP6f) to a 30-min exposure with 3 mg/ml of MβCD on the frequency of GCaMP6f Ca2+ oscillations (B; Control, n = 58; MβCD, n = 78), peak GCaMP6f Ca2+ transients (C; Control, n = 58; MβCD, n = 70), area under the curve of GCaMP6f Ca2+ transients (D; Control, n = 58; MβCD, n = 70) and FWHM GCaMP6f Ca2+ transients (E; Control, n = 58; MβCD, n = 70). The Control (light blue boxes) and MβCD (light gray boxes) datasets in B–F are from the same animals (N = 4). For each dataset in the latter panels, the mean is indicated by a filled black square with the colored boxes and whiskers delimiting the 25th and 75th percentile, and the 10th and 90th percentile of the pooled data, respectively, and small dots individual data points. For all panels, *** indicates a significant difference between means with P < 0.001.

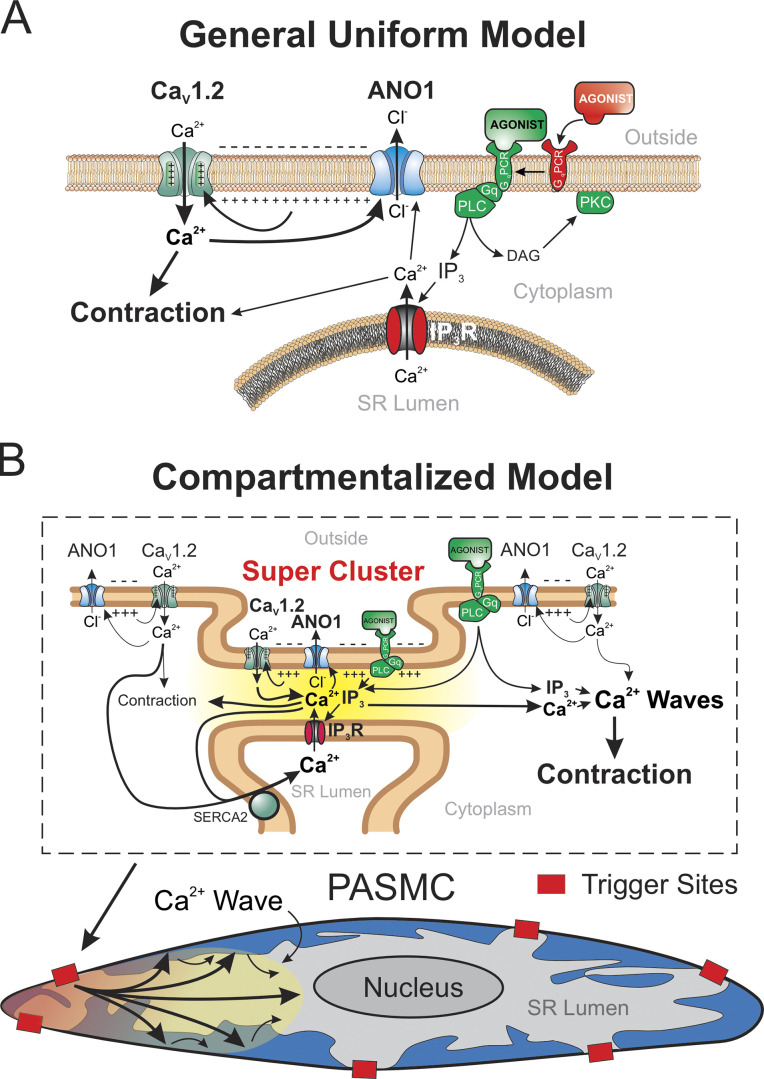

Discussion

We have demonstrated that the contribution of ANO1 to agonist-mediated signaling in mouse PASMCs is more complex than that predicted from the simple working model of a widespread and uniform positive feedback loop between Ca2+ entry through VGCC and the sustained membrane depolarization caused by Ca2+ activation of ANO1 (Fig. 12 A). Instead, we conclude that the fraction of the contraction to 5-HT that is membrane potential-dependent requires the coordinated interaction of ANO1, CaV1.2, and IP3R colocalized in a finite number of superclusters spread across the cell length (Fig. 12 B). This interaction is responsible for evoking and sustaining intracellular Ca2+ oscillations that propagate along the main axis of the cell, with little evidence for cell-to-cell transmission. Our data are consistent with previous reports showing that 5-HT or endothelin-1 triggered asynchronous Ca2+ oscillations in small arteries and arterioles of mouse lung slices (Perez and Sanderson, 2005; Perez-Zoghbi and Sanderson, 2007). Simultaneous measurements of Ca2+ transients and changes in luminal size, as an index of constriction, showed that the force of arteriolar contraction to agonists mainly depends on the frequency of Ca2+ oscillations. The observation that the constriction produced by agonists is sustained and non-oscillatory is hypothesized to be caused by the summation in space and time of force produced by individual myocytes and the fact that muscle relaxation is much slower than the Ca2+ transients triggering force production (Perez and Sanderson, 2005).

Figure 12.

Hypothetical models of EC coupling involving ANO1, CaV1.2, and IP3R during agonist-mediated contraction of mouse pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells. (A) General uniform model depicting the activation of ANO1 by both Ca2+ release from IP3-sensitive SR Ca2+ stores and Ca2+ entry through CaV1.2. In this model, the three ion transporters are evenly distributed in the membrane and are not physically coupled. The depolarization is maintained by the positive feedback loop established by CaV1.2-mediated activation of Cl− efflux through ANO1 and its impact on the state of activation of CaV1.2 through regulation of membrane potential. (B) Schematic diagram illustrating the local interaction of ANO1, CaV1.2 with IP3R and their impact on membrane potential, Ca2+ entry, and contraction. In this model, the three ion channels are physically coupled in a restricted number of sites (Super Cluster) distributed across the long axis of the cell (shown as red boxes in the bottom diagram) and are organized for compartmentalized Ca2+ signaling as highlighted by the yellow gradient area between the PM and segments of the SR in the close vicinity of the PM (top diagram). These compartmentalized areas serve the role of trigger sites for initiating Ca2+ waves that can then propagate through Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release (CICR). Ca2+ entry through CaV1.2, which is maintained by the depolarization caused by ANO1, supports the microenvironment that is necessary to promote the propagation of the Ca2+ waves by CICR and to reload SR Ca2+ stores. PASMC: pulmonary artery smooth muscle cell; IP3: inositol-triphosphate; GqPCR: Gq-protein coupled receptor; PLC: phospholipase C; SERCA2: type 2 Ca2+-ATPase of the SR.

A remarkable observation of the present study was the similar inhibitory effectiveness of suppressing ANO1, VGCC, or Ca2+ release from the SR on the contraction to 5-HT. These results suggest that the contraction requires all three elements to maintain force production. This is supported by Ca2+ imaging experiments showing that similar treatments strongly inhibited or abolished Ca2+ oscillations in myocytes from intact pulmonary arteries of mice conditionally expressing the Ca2+ biosensor protein GCaMP3 in smooth muscle cells. We hypothesize that cyclical Ca2+ release from IP3R triggers self-regenerative Ca2+ waves that propagate along the long axis of the cell through Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release. Whether this process also involves ryanodine (RyR) receptor-sensitive SR Ca2+ pools is unclear. Some studies found no role for RyR in response to agonists (Hamada et al., 1997; Hyvelin et al., 1998; Zheng et al., 2005; Henriquez et al., 2018), while a few others revealed a significant contribution of RyR and crosstalk between RyR- and IP3R-sensitive Ca2+ pools (Yang et al., 2005; Clark et al., 2010).