Abstract

Background

Traumatic Dental Injuries (TDI) have emerged as a very significant public health and social problem, especially among children and adolescents. The aim of this study was to investigate the prevalence and associated risk factors of traumatic dental injuries to permanent anterior teeth in school going children of Kolkata aged 7-14 years.

Method

A cross-sectional study was conducted among 3762 school going children attending various private and public schools of Kolkata aged 7–14 years. A multistage random clustering sampling technique was adopted to select the children.Type of trauma using Ellis and Davey classification of fractures along with Andresen’s Epidemiological Classification of Traumatic Injuries to Anterior Teeth, including WHO codes, was used. All values were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Results

Prevalence of TDI to anterior teeth was found to be 9.89%. The mean age of children who presented with TDI was 11.06 ± 1.99.years. The most common place of occurrence of TDI was home. Falls were the most common causes of trauma. Children belonging to higher socioeconomic status were observed to have an increased prevalence of TDIs.The highest potential risk factor for the occurrence of trauma was a past history of trauma.

Conclusion

Present study found a prevalence of 9.89%, and a very low percentage of children had received treatment.

Keywords: Trauma, Permanent teeth, Children, Risk factors, Prevalence

Introduction

Traumatic dental injuries (TDI) have consequences not only on children but also on their families and thus, pose serious public health and social concerns.1 TDI can directly or indirectly affect a child’s life by affecting the position of the tooth in the arch or by affecting a child’s appearance, mastication, and speech, thus reducing the overall quality of life. They may ultimately cause low confidence, self-esteem, function, and aesthetics throughout life.2

Traumatic dental injuries (TDI) have been projected as the fifth most prevalent disease worldwide.3As per literature, the global prevalence of traumatic dental injuries has been estimated to be 13 to 17.5 percent, while the pooled prevalence of TDI in India was estimated as 13%.4,5

Numerous risk factors for TDI have already been identified, and complex interaction between them is well established. Age, environment (school, home, etc.), gender, and socioeconomic background are some of the risk factors already explored worldwide.6,7

One aspect of TDI that has largely been left unexplored by many investigators is the influence of the previous history of trauma on future susceptibility to any further episode of TDI i.e. multiple dental trauma episodes (MDTE). The occurrence of MDTE to the same teeth (RTT-repeated traumatized tooth) has been reported to range from 8 to 45%.8,9

Epidemiological data provide a basis for the evaluation of the existing situation and associated risk factors. Accounting for risk factors is critical to the assessment of proper precautions needed to avoid further trauma, its undesirable consequences, formulating effective preventive strategies, and healthcare policies. Literature regarding TDI was found to be scant, with only one study determining the incidence of TDIs, which was undertaken thirty years back.10

Hence the present study was designed with the aim to determine the prevalence and associated risk factors of traumatic dental injuries to permanent anterior teeth in school going children of Kolkata. The novelty of the present study lies in the fact that, to the best of our knowlegde, it the first epidemological study conducted in this particular part of the country that determines the prevalence and encompasses multiple attributes of TDIs of that region.

Materials and Method

The present study was designed to determine the prevalence of anterior teeth trauma and associated risk factors.

Study design

Cross-sectional Study.

Study area

Public and Private Schools within the limits of the Municipal Corporation of Kolkata.

Inclusion criteria

Children belonging to both the sexes attending different schools of Kolkata who had entered 7th or 14th year on their last birthday and in whom permanent anterior teeth and permanent first molars had erupted, were included in this study after taking consent from the parents and permission from the head of the school.

Exclusion criteria

Noncooperative children, children with special healthcare needs, those who were undergoing orthodontic therapy, ones having teeth with developmental defects or having lost their teeth for reasons other than traumatic dental injuries, along with children who had clinical evidence of trauma, but providing incoherent history were excluded from the study. Besides these, traumatic dental injuries to the deciduous teeth and root fractures were excluded from the study as radiographs were not taken.

The approval for the study was obtained from the Institutional Ethical Review Board vide letter number DS/07/PPD/2019.

Sampling technique

Multistage Random Cluster Sampling Technique.

Sample size calculation

An average prevalence of 10% of traumatic dental injuries was presumed for the calculation of the sample size conferring with results obtained from previous studies.11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 The minimum sample size to meet the requirement was estimated to be 3300 children. Effect of intracluster correlation (ICC, or the strength of correlation within clusters) was regarded for sample size calculation, and therefore, an impact factor of at least 1.5 was taken to eliminate the destructive effect of clusters.

The sample size was calculated using the following formula.17,18

where P = positive character (assumed prevalence) = 10%

Q = 100-p = 90, Relative precision of 10% was taken, thus I = 10% of P = 1.

Deff: Design Effect (1.5).

Assuming a dropout or nonresponse of 10%, the final study population comprised 3762 children.

A list comprising all private and public schools of Kolkata city was obtained from the directorate of school education. Kolkata city was divided into four geographical zones, namely North Kolkata, East Kolkata, South Kolkata, and Central Kolkata that were identified as focal points for the present study in order to obtain a sample representative of 7 to 14-year-old school going children of Kolkata. One public and one private school from each zone were selected randomly using the lottery method. This was followed by selection of children from the selected schools as per the inclusion criteria. At least 450 children were randomly selected from each school, ensuring an almost equal number of boys and girls.

A letter was sent to the parents of the selected children explaining the aim, characteristics, and importance of the study and asking for their participation. The majority of parents agreed on their children participating in the study, thereby achieving a response rate of 90%.

A questionnaire was sent to parents of children in order to assess their level of education, occupation and family income and assess their socioeconomic status as per the Kuppuswamy scale. An updated version of the Kuppuswamy scale was used because of the increase in the price index, as this scale is based on the consumer price index.19,20

A prior notification regarding the date and time of examination of the school children was sent to school principals. The clinical examiners were calibrated prior to the study in order to control reliability. Clinical instructions and calibration took place at the Department of Pedodontics and Preventive Dentistry of our institution. A presurvey calibration was performed in two series of clinical examinations on 50 children (which were excluded from the final sample) at a 3-week interval in order to establish intraexaminer reproducibility. The recommended level of interexaminer consistency in recording dental trauma was achieved. During the survey, a double examination of approximately 10% of the children was performed so as to assess intraexaminer and interexaminer variability in the use of the diagnostic criteria. The Cohens’ Kappa coefficient values on interexaminer consistency/reliability in the diagnosis of dental trauma were found to be satisfactory (>0.82).

A closed-ended pretested and prevalidated proforma was prepared to collect data. For ensuring the correct past history of dental trauma, the parents were asked to specify the age of the child, place, and timing of separate incidences of dental trauma along with details of treatment if sought after traumatic dental injury. The history was supplemented by clinical examination to look for signs of crown discoloration, loss of tooth due to trauma, and the presence of fistula as a sequel to dental trauma. ELLIS and DAVEY’S (1960) classification, along with Andresen’s Epidemiological Classification of Traumatic Injuries to Anterior Teeth, including WHO codes, was used to evaluate traumatic dental injuries to anterior teeth. The American Dental Association (ADA) type-3 technique was used for examination. CPI probe was used to measure the degree of overjet as described in WHO Basic Oral Health Survey Guidelines.21

The TDI examination and a structured interview were held within the school premises in a separate room and under natural light during school hours. The permanent anterior teeth were cleaned with sterile gauze and examined for TDI using a mouth mirror, a dental explorer. A visual examination to determine lip coverage was done as the child entered the examination room without the child’s awareness.

The data were processed and analyzed by means of SPSS Version 19.0 (Chicago, IL, USA). The Chi-square test was used to compare qualitative data. Independent Student T-test was applied to continuous variables. Multiple logistic regression analysis and adjusted odds ratios were used to identify potential predictors of traumatic dental injuries, which also helped to eliminate the effect of confounding variables. Statistical significance was set at p-value < 0.05.

Results

A total of 3762 children (1684 boys and 2078 girls) were examined and interviewed for TDI to anterior teeth. In total, 372 (9.89%) children were found to have TDI involving 457 teeth, out of which 219 were boys and 153 girls, and the comparison between the gender was statistically significant. The mean age of children who presented with TDI was 11.06 ± 1.99 years. The prevalence of TDI was significantly higher in the age group 12-14 years as compared to the age group 7–9 years. The majority of TDI occurred at home (49%) followed by school (22.1%) and playground (8.4%). Traumatic dental injuries occurring at home were significantly more in females (Table 1). The main cause of TDI among school going children of Kolkata was fall (52%) followed by collision (14.3%). Falls occurring mainly at a child’s home and school were found to be the leading cause of TDIs in children (Table 2). The majority of children (80.2%) had sustained an injury to a single tooth only, while a lower proportion had suffered injuries to two and three teeth, 17.60% and 2.20%, respectively. The tooth most commonly involved in traumatic dental injuries was the maxillary right central incisor. Maxillary teeth were involved more than the mandibular teeth. Most of the children presented mainly Ellis Class I and Class II fractures (Fig. 1). Traumatic dental injuries as per Andresen’s Epidemiological Classification of Traumatic Injuries to Anterior Teeth, including WHO (Table 3).

Table 1.

Distribution of dental trauma subjects according to gender and place of injury.

| Place of Injury | Sex |

Chi-Square Value | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female |

Male |

|||||

| N | % | N | % | |||

| Home | 100 | 54.6 | 83 | 45.4 | 45.606 | 0.000 |

| Play Ground | 8 | 25.8 | 23 | 74.2 | ||

| Park | 2 | 20 | 8 | 80 | ||

| School | 30 | 36.6 | 52 | 63.4 | ||

| Street | 7 | 36.8 | 12 | 63.2 | ||

| Unknown | 6 | 12.8 | 41 | 87.2 | ||

Table 2.

Distribution of dental trauma subjects according to cause and place of injury.

| Cause Of Injury | Place of Injury |

Chi-Square | p-value value |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Home |

PlayGround |

Park |

School |

Street |

Unknown |

|||||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |||

| Biting Hard Food | 4 | 2.2 | 1 | 3.2 | 2 | 20.0 | 1 | 1.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 6.4 | 2818.968 | 0.000 |

| Collision | 14 | 7.7 | 11 | 35.5 | 1 | 10.0 | 15 | 18.3 | 2 | 10.5 | 3 | 6.4 | ||

| Fall | 142 | 77.6 | 15 | 48.4 | 5 | 50.0 | 45 | 54.2 | 3 | 15.8 | 19 | 40.4 | ||

| Road Traffic Accident | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 12 | 63.2 | 12 | 25.5 | ||

| Sports | 14 | 7.7 | 2 | 6.5 | 2 | 20.0 | 12 | 14.6 | 2 | 10.5 | 3 | 6.4 | ||

| Unknown | 15 | 8.2 | 1 | 3.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 4.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Violence | 14 | 7.7 | 1 | 3.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 7.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 7 | 14.9 | ||

Fig. 1.

Frequency distribution of dental trauma as per Ellis and Davis Classification.

Table 3.

Frequency distribution of dental trauma subjects as per Andresen's epidemiological classification of traumatic injuries to anterior teeth, including WHO codes.

| WHO Classification | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| No Trauma | 3391 | 90.1 |

| Treated Dental Injury | 27 | 0.7 |

| Enamel Fracture only | 247 | 6.6 |

| Enamel/Dentin Fracture | 78 | 2.1 |

| Pulp Injury | 10 | 0.27 |

| Missing Tooth due to trauma | 9 | 0.23 |

| Excluded tooth | 0 | 0.0 |

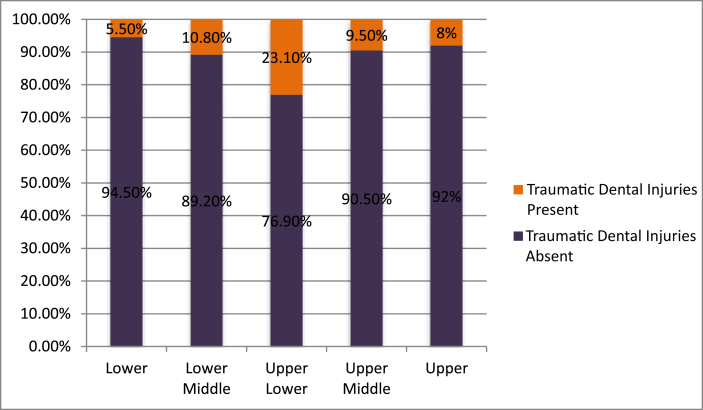

Children with Class 2 Div I malocclusion were seen to be more affected by TDI than children with Class 1 M relation and Class 2 Div II malocclusion. The difference, however, was found to be statistically insignificant. Children belonging to upper socioeconomic status were found to be more involved in TDI than those belonging to lower socioeconomic status (Fig. 2). A statistically significant difference was observed between various socioeconomic groups for TDI.

Fig. 2.

Frequency distribution of dental trauma as per socioeconomic status of the study population.

The overall proportion of treated cases of TDI was low (7.2%) in the current sample, and a comparison of the socioeconomic status for treated cases of TDI (Upper Middle 9.52%/, Upper Lower 4.7%/, Lower middle = Lower - 7.4%) showed no significant difference. The lower-middle and lower groups were clubbed for ease of statistical analysis. Children with a previous episode of trauma had a significantly higher prevalence of TDI compared to those who did not have any past history of trauma (Fig. 3). The prevalence of dental trauma according to different variables was analyzed (Table 4).

Fig. 3.

Frequency distribution of dental trauma as per previous history of trauma.

Table 4.

Prevalence of trauma to permanent anterior teeth according to the variables analyzed.

| Variables | N = 372 | Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 153 | 7.4 |

| Male | 219 | 13.0 |

| School | ||

| Government | 318 | 10.8 |

| Private | 54 | 6.6 |

| Socioeconomic Status | ||

| Lower | 7 | 5.5 |

| Lower middle | 221 | 10.8 |

| Upper | 18 | 23.1 |

| Upper Lower | 42 | 9.5 |

| Upper Middle | 84 | 8.0 |

| Previous Dental Trauma | ||

| Absent | 235 | 7.1 |

| Present | 137 | 31.9 |

| Overjet | ||

| Cross bite | 0 | 0.0 |

| Decreased | 30 | 8.0 |

| Increased | 99 | 17.7 |

| Normal | 236 | 8.6 |

| Open bite | 7 | 11.7 |

| Lip Coverage | ||

| Competent | 280 | 8.4 |

| Incompetent | 92 | 21.3 |

| Malocclusion | ||

| Class1 | 320 | 9.9 |

| Class 2 Div 1 | 36 | 12.5 |

| Class 2 Div 2 | 10 | 9.3 |

| Class 3 | 6 | 4.5 |

Adjusted Odds ratio by Mixed-effects logistic regression analysis showed that male gender, incompetent lips, increased overjet, prior history of trauma were significant risk factors for the TDI (Table 5).

Table 5.

Likelihood of TDIs according to the adjusted odds ratio by mixed-effects logistic regression.

| Variable | OR | 95% C.I. | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 1 | ||

| Male | 1.43 | 0.89–1.92 | 0.09 | |

| Past history of trauma | No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 2.34 | 1.32–6.34 | 0.03 | |

| School Type | Government | 1 | ||

| Private | 1.32 | 0.23–3.89 | 0.09 | |

| Lip Coverage | Competent | 1 | ||

| Incompetent | 5.32 | 3.34–9.34 | <0.01 | |

| Occlusion | Class 1 | 1 | ||

| Class 2 Div 1 | 1.89 | 0.34–4.89 | 0.21 | |

| Class 2 Div 2 | 1.45 | 0.12–5.32 | 0.32 | |

| Class 3 | 1.67 | 0.98–3.23 | 0.09 | |

| Overjet | Cross Bite | 2.98 | 1.23–4.57 | 0.04 |

| Decreased | 3.82 | 2.23–7.45 | 0.03 | |

| Increased | 3.02 | 1.98–8.98 | 0.04 | |

| Normal | 1 | |||

| Open Bite | 1.03 | 0.32–4.34 | 0.07 | |

| Socioeconomic Status | Lower | 1 | ||

| Lower Middle | 1.32 | 0.78–3.34 | 0.34 | |

| Upper | 2.98 | 0.64–5.58 | 0.32 | |

| Upper Lower | 1.34 | 0.99–4.78 | 0.12 | |

| Upper Middle | 1.89 | 0.34–3.39 | 0.52 | |

| Age | 7–9 | 1 | ||

| 10–12 | 1.23 | 0.24–3.99 | 0.09 | |

| 12–14 | 2.65 | 1.02–6.39 | 0.03 |

Multinomial logistic regression analysis showed that the highest potential risk factor for the occurrence of TDI was a past history of trauma followed by increased overjet and lip coverage. These three variables showed a statistically significant association to TDI (p-value < 0.05) (Table 6).

Table 6.

Likelihood of traumatic injuries according to the odds ratio by multinomial logistic regression.

| Variable | Model Fitting Criteria - 2 Log Likelihood of Reduced Model | Likelihood Ratio Tests Chi-square | Degree of Freedom | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 234.3 | 0 | 0 | – |

| Past history of trauma | 298 | 6.32 | 1 | <0.01 |

| School Type | 253 | 1.32 | 1 | 0.07 |

| Lip Coverage | 273 | 4.48 | 1 | 0.03 |

| Occlusion | 232 | 0.45 | 3 | 0.23 |

| Overjet | 281 | 5.02 | 4 | 0.02 |

| Socioeconomic Status | 245 | 1.78 | 4 | 0.12 |

| Age | 239 | 1.98 | 1 | 0.23 |

Discussion

The present study identified the prevalence of traumatic dental injuries to be 9.89%. This prevalence may be considered low as compared to global prevalence, as well as prevalence obtained from results obtained from some national studies. Other national studies by Patel et al. (8.79%), Hegde et al. (7.3%), Ain et al. (9.3%), reported a lower prevalence rate of TDI.11, 12, 13 The wide variation in prevalence studies could be possibly attributed to different study settings, different classification systems used, varying environmental factors, and different examination methods used.

A statistically significant influence of gender was observed on the occurrence of trauma. This could be attributed to the fact that in India, females are confined to homes, and males are more indulged in outdoor activities because of conservative societal norms, various cultural factors, as well as behavioral traits of both genders. Similar results were obtained from studies conducted by Patel et al, Hegde et al, Ain et al, Dighe et al, Juneja et al, and Garg et al.11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 While Tovo et al. in a study conducted in Canoas, Brazil, reported no significant difference between boys and girls, which is in contrast to the present study.22This disparity could be explained by the difference in the sociodemographic and behavioral attributes among the samples studied and equal exposure of both genders to etiologic factors of trauma in Latin American society.

Fall was the most frequent cause of dental trauma. It was in concurrence with results obtained with various other studies11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16,23 Similar results were obtained from the study done by Nicolau et al. who found collision to be the cause in 15% of the cases.24 In Kolkata, children play football more often than any other game and that too in muddy grounds, which increases the probability of falls. Dental Trauma due to biting some hard substance was reported; two of them had given a history of pencil biting. These findings are lesser than those reported by Nicolau et al, and Soriano et al.23,24 In the present study, twenty children were unaware of the cause of dental trauma. The likely cause for this could be that intensity of trauma was so less that the child could not recall it.

The home was the main location for TDIs. The results corroborates with the results obtained from many other studies.11,12,14,15 This may be attributed to the fact that high outdoor temperatures during the summer season in Kolkata that ranges between 39 °C to 43 °C confines the children to home most of the time, thereby getting indulged in indoor activities. Moreover children spend comparatively less time at school and the playground. Contrary to the results of the present study, Tapias et al. found that maximum injuries occurred in the streets (52.4%) while Garg et al. showed that the main location for the dental injuries was schools (63.2%).16,25 In the present study, boys incurred more injuries at school and streets, whereas most of the injuries in the girls occurred at home. This can also be due to the reason that females are confined to homes and males are more involved in outdoor activities in India.

Enamel fracture was the most common type of fracture. Similar results were obtained from studies conducted by Hegde et al, Ain et al, Juneja et al. and most of the epidemiological studies.12,13,15It could be due to the reason that trauma was not so severe, thereby leading to enamel fractures only. Results of the present study are contrary to the results obtained from the study by Soriano et al.23 Moreover, other studies with a high prevalence of enamel only fractures were also cross-sectional studies conducted in various schools.

A higher prevalence of traumatic dental injuries to anterior teeth was found in children from higher socioeconomic status families. The reason for such finding could be since the children belonging to higher socioeconomic status have more access to sports, leisure goods, and equipments that heighten the chances of sustaining traumatic dental injuries. Contrary findings were obtained by Soriano et al. and Ain et al. who reported that lower socioeconomic groups were more prone to TDIs while Fakhruddin et al, found a higher TDI prevalence in the middle-class socioeconomic group.13,23,26 Similar results were found in studies done by Bendo et al, from Brazil.27 Also different socioeconomic pattern shared by different countries, might explain this wide variation in results obtained from different studies. Moreover, only a few studies have included socioeconomic status in their reports, and yet there is no conclusive scientific evidence of the relationship of SES with TDI.28

Increased overjet emerged as a very important independent risk factor associated with TDIs in this study. This was clearly because an increased overjet increases the exposure of permanent anterior teeth, making them more vulnerable to TDIs. Results were in corroboration with results obtained from studies done by Patel et al, Juneja et al and Soriano et al.11,15,23 The above observation reiterates the fact that early orthodontic correction of overjet is tremendously required for the prevention of TDIs.

Like most of the previous studies, TDIs were more frequent among school children with incompetent lip seals compared to those with competent lips. The absence of effective lip seal makes a tooth more vulnerable to trauma to the teeth by devoiding it of cushioning effect provided by lips. This was in agreement with the findings of many other studies.13,14

Maxillary teeth were observed to have an increased propensity to trauma, which is in accordance with results obtained from various other studies of similar nature.13,14 The position of the maxillary teeth make them prone to direct assault, thereby more involvement in TDIs’; moreover, the attachment of the maxilla to the cranial base is rigid and does not dissipate the forces acting upon the maxillary incisors.

Various factors of human behavioral traits like tendency to take a risk, emotionally stressful states, the presence of debilitating illness, learning difficulties, etc. predispose an individual to MDTE.8As per results of the current study, the highest potential risk factor for the occurrence of TDI was a past history of trauma followed by an increased overjet and inadequate lip coverage. This can perhaps be explained by the fact that children are in a stage of acquiring fine motor skills, which predisposes them to collisions and falls.29 Certain anatomical skeletal and dental features like bimaxillary protrusion, increased overjet, inadequate lip coverage can lead to MDTE. Moreover, as children reach puberty, especially males, they start showing some aggressive behavioral traits that might predispose them to repeated episodes of traumatic dental injuries.30 This necessitates the need to develop a risk profile for patients who sustain MDTE to reduce the dramatic effects of repeated dental traumas.

One alarming finding from the present study was that only a few children had got treatment done for traumatic dental injury. As per the results of the present study, a majority of TDIs were only enamel fractures, which did not have any functional and aesthetic implications. In addition to this, inadequate knowledge of parents and teachers regarding the emergency management of trauma might be a reason for such findings. For encompassing the complexities of dental trauma epidemiology, additional studies, both cross-sectional as well as longitudinal nature, are required in representative populations.

Prevention should consider a number of characteristics such as oral predisposing factors, environmental determinants, and human behavioral factors to reduce the probability of occurrence of traumatic dental injuries. Proper monitoring and supervision by teachers, parents and enhancing knowledge of doctors, paramedic staff through education campaigns can prove to be a game changer in the field of TDI.

Limitations of study

The present study had certain limitations, like the crosssectional design. Dependence on self-reported nature of the previous history of dental trauma leading to response bias. Impact of nonresponse on results of the study.

Conclusion

Within the limitations of the present study, we found a high prevalence of traumatic dental injuries. Additionally, it was inferred that a low percentage of children received treatment for traumatic injuries. It is revealed that there is a need to inform the public of what they should do in case of dental trauma and how important it is to contact a dentist immediately. Additionally, professionals, teachers, and paramedic technicians should be knowledgeable concerning TDI in school going children and adolescents, enabling them to provide better preventive measures and better clinical emergency management procedures of TDI in the future to prevent multiple dental trauma episodes.

Disclosure of competing interest

The authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Bendo C.B., Paiva S.M., Abreu M.H., Figueiredo L.D., Vale M.P. Impact of traumatic dental injuries among adolescents on family's quality of life: a population-based study. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2014;24(5):387–396. doi: 10.1111/ipd.12083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abanto J., Tello G., Bonini G.C., Oliveira L.B., Murakami C., Bonecker M. Impact of traumatic dental injuries and malocclusions on quality of life of preschool children: a population-based study. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2015;25(1):18–28. doi: 10.1111/ipd.12092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petti S., Glendor U., Andersson L. World traumatic dental injury prevalence and incidence, a meta-analysis-One billion living people have had traumatic dental injuries. Dent Traumatol. 2018;34(2):71–86. doi: 10.1111/edt.12389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petti S., Andreasen J.O., Glendor U., Andersson L. The fifth most prevalent disease is being neglected by public health organisations. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6(10) doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30380-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tewari N., Mathur V.P., Siddiqui I., Morankar R., Verma A.R., Pandey R.M. Prevalence of traumatic dental injuries in India: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Indian J Dent Res. 2020;31(4):601–614. doi: 10.4103/ijdr.IJDR_953_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glendor U. Aetiology and risk factors related to traumatic dental injuries--a review of the literature. Dent Traumatol. 2009;25(1):19–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.2008.00694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lam R. Epidemiology and outcomes of traumatic dental injuries: a review of the literature. Aust Dent J. 2016;61(suppl 1):4–20. doi: 10.1111/adj.12395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glendor U., Koucheki B., Halling A. Risk evaluation and type of treatment of multiple dental trauma episodes to permanent teeth. Endod Dent Traumatol. 2000;16(5):205–210. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-9657.2000.016005205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pissiotis A., Vanderas A.P., Papagiannoulis L. Longitudinal study on types of injury, complications and treatment in permanent traumatized teeth with single and multiple dental trauma episodes. Dent Traumatol. 2007;23(4):222–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.2006.00442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sarkar S., Basu P.K. Incidence of anterior tooth fracture in children. J Indian Dent Assoc. 1981;53:317. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel M.C., Sujan S.G. The prevalence of traumatic dental injuries to permanent anterior teeth and its relation with predisposing risk factors among 8-13 years school children of Vadodara city: an epidemiological study. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2012;30(2):151–157. doi: 10.4103/0970-4388.99992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hegde R., Agrawal G. Prevalence of traumatic dental injuries to the permanent anterior teeth among 9- to 14-year-old schoolchildren of Navi Mumbai (Kharghar-Belapur region), India. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2017;10(2):177–182. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10005-1430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ain T.S., Lingesha Telgi R., Sultan S., et al. Prevalence of traumatic dental injuries to anterior teeth of 12-year-old school children in Kashmir, India. Arch Trauma Res. 2016;5(1) doi: 10.5812/atr.24596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dighe K., Kakade A., Takate V., Makane S., Padawe D., Pathak R. Prevalence of Traumatic Injuries to Anterior Teeth in 9–14 Year School-going Children in Mumbai, India. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2019;20(5):622–630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Juneja P., Kulkarni S., Raje S. Prevalence of traumatic dental injuries and their relation with predisposing factors among 8-15 years old school children of Indore city, India. Clujul Med. 2018 Jul;91(3):328–335. doi: 10.15386/cjmed-898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garg K., Kalra N., Tyagi R., Khatri A., Panwar G. An appraisal of the prevalence and attributes of traumatic dental injuries in the permanent anterior teeth among 7-14-year-old school children of North East Delhi. Contemp Clin Dent. 2017 Apr-Jun;8(2):218–224. doi: 10.4103/ccd.ccd_133_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirby A., Gebski V., Keech A.C. Determining the sample size in a clinical trial. Med J Aust. 2002;177(5):256–257. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2002.tb04759.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alimohamadi Y., Sepandi M. Considering the design effect in cluster sampling. J Cardiovasc Thorac Res. 2019;11(1):78. doi: 10.15171/jcvtr.2019.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuppuswami B. Netaji Subhash Marg; 1981. Manual of Socio Economic Scale (Urban) Delhi: Mansayan 32. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumar B.P.R., Dudala S.R., Rao A.R. Kuppuswamy's socio-economic status scale–a revision of economic parameter for 2012. Int J Res Dev Health. 2013;1(1):2–4. [Google Scholar]

- 21.WHO . 4th ed. AITBS Publishers; India: 1997. Oral Health Surveys, Basic Methods. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tovo M.F., dos Santos P.R., Kramer P.F., Feldens C.A., Sari G.T. Prevalence of crown fractures in 8-10 years old schoolchildren in Canoas, Brazil. Dent Traumatol. 2004;20(5):251–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.2004.00253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soriano E.P., Caldas Ade F., Jr., Diniz De Carvalho M.V., Amorim Filho Hde A. Prevalence and risk factors related to traumatic dental injuries in Brazilian schoolchildren. Dent Traumatol. 2007;23(4):232–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.2005.00426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nicolau B., Marcenes W., Sheiham A. Prevalence, causes and correlates of traumatic dental injuries among 13-year-olds in Brazil. Dent Traumatol. 2001;17(5):213–217. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-9657.2001.170505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tapias M.A., Jiménez-García R., Lamas F., Gil A.A. Prevalence of traumatic crown fractures to permanent incisors in a childhood population: Móstoles, Spain. Dent Traumatol. 2003;19(3):119–122. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-9657.2003.00141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fakhruddin K.S., Lawrence H.P., Kenny D.J., Locker D. Impact of treated and untreated dental injuries on the quality of life of Ontario school children. Dent Traumatol. 2008;24(3):309–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.2007.00547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bendo C.B., Scarpelli A.C., Vale M.P., Araujo Zarzar P.M. Correlation between socioeconomic indicators and traumatic dental injuries: a qualitative critical literature review. Dent Traumatol. 2009;25(4):420–425. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.2009.00803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Corrêa-Faria P., Martins C.C., Bönecker M., Paiva S.M., Ramos-Jorge M.L., Pordeus I.A. Absence of an association between socioeconomic indicators and traumatic dental injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dent Traumatol. 2015;31(4):255–266. doi: 10.1111/edt.12178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Borum M.K., Andreasen J.O. Therapeutic and economic implications of traumatic dental injuries in Denmark: an estimate based on 7549 patients treated at a major trauma centre. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2001;11(4):249–258. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-263x.2001.00277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Forbes E.E., Dahl R.E. Pubertal development and behaviour:hormonal activation of social and motivational tendencies. Brain Cognit. 2010;72(1):66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]