TO THE EDITOR:

In 2014, the American Society of Hematology (ASH), in collaboration with the McMaster University GRADE Centre, initiated the development of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines on venous thromboembolism (VTE). To date, 10 guidelines on VTE have been published.1 However, clinical practice guidelines can be considered outdated if they do not include recent and valid evidence or reflect clinicians’ current experiences and patients’ values. Therefore, to meet the standards for trustworthy clinical practice guidelines,2 the ASH Clinical Practice Guidelines are committed to implementing a transparent and standardized monitoring and updating process for each guideline, which started in 2021. In response to this, an updated literature search on prophylaxis for medical patients who were hospitalized and those who were not hospitalized was carried out. The purpose of this article is to report the main findings from this updated literature search.

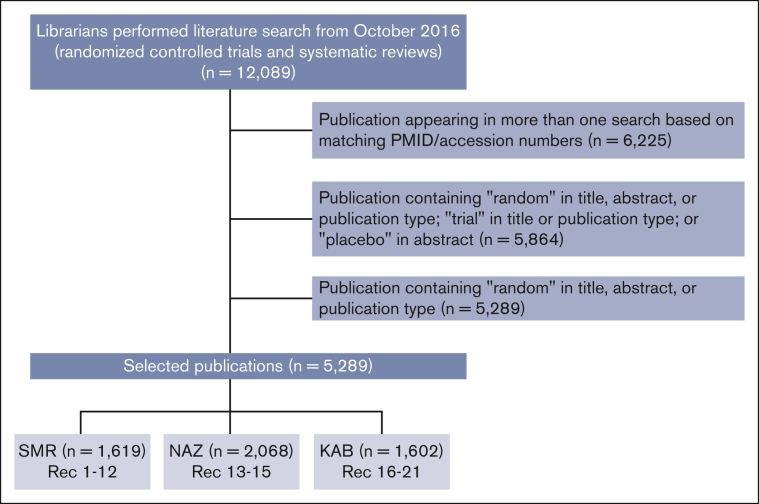

The original ASH guideline on prophylaxis for medical patients who were hospitalized and those who were not hospitalized was published in 2018.3 The guideline contains 19 recommendations (Table 1) and includes results from a literature search from 1946 to November 2016. To select references for monitoring and updating the guideline, the librarians performed a search on 27 April 2022. They assessed MEDLINE and EMBASE databases from October 2016 to 26 April 2022. This search resulted in 5289 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and systematic reviews (SRs) (Figure 1). The publications were then distributed to S.M.R., K.A.B., and N.A.Z., who composed the ASH Guideline Monitoring Expert Working Group. Each expert selected the publications of interest by reading its title and/or abstract, when applicable. When it corresponded to a RCT or SR related to the subject of the guideline, the publication was selected, and a full reading of the manuscript was carried out. All 3 reviewers came to consensus that a given study would change a previous recommendation. A flowchart of the search and selected references is shown in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Recommendations on prevention of VTE based on the patient populations and interventions

| Patients who are acutely ill: pharmacological prophylaxis, addressing the following comparisons: |

| Parenteral anticoagulant vs no parenteral anticoagulant |

| LMWH vs unfractionated heparin |

| Fondaparinux vs low molecular weight heparin or unfractionated heparin |

| Patients who are critically ill: pharmacological prophylaxis, addressing the following comparisons: |

| Any heparin vs no heparin |

| LMWH vs unfractionated heparin |

| Patients who are acutely or critically ill: mechanical prophylaxis, addressing the following comparisons: |

| Mechanical vs pharmacological prophylaxis |

| Mechanical vs no prophylaxis |

| Mechanical combined with pharmacological vs mechanical alone |

| Mechanical combined with pharmacological vs pharmacological alone |

| Intermittent pneumatic compression stockings vs graduated compression stockings |

| DOACs in medical patients who are acutely ill |

| DOACs vs prophylactic LMWH |

| Extended-duration DOACs vs shorter-duration non-DOAC prophylaxis |

| Extended-duration outpatient prophylaxis vs inpatient-only prophylaxis |

| Medical patients who are acutely ill |

| Medical patients who are critically ill |

| Patients who are chronically ill or those in nursing home |

| Pharmacological prophylaxis vs no prophylaxis |

| Medical outpatients with minor provoking factors for VTE (eg, immobility, minor injury, illness, and infection) |

| Prophylaxis vs no prophylaxis |

| Long-distance travelers: prophylaxis addressing the following comparisons: |

| Graduated compression stockings |

| LMWH |

| Aspirin vs no prophylaxis |

Adapted from the article by Schünemann et al.3

DOACS, direct oral anticoagulants; LMHW, low molecular weight heparin.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the searching process of the publications. KAB, Kenneth A. Bauer; NAZ, Neil A. Zakai; PMID, PubMed Identifier; Rec, recommendation; SMR, Suely M. Rezende.

We did not identify any new study that would change the current recommendations. No RCTs or SRs that would affect the current recommendations were identified. However, since the publication of the “ASH 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: prophylaxis for hospitalized and nonhospitalized medical patients,”3 some studies have been published on this subject, which deserve comment.

Mechanical thromboprophylaxis in patients who are hospitalized and critically ill (recommendation 9)

The PREVENT Trial randomized 2003 adult patients who were critically ill to pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis alone (unfractionated or low molecular weight heparin) vs pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis plus intermittent pneumatic compression4 The latter did not result in a significantly lower incidence of proximal lower limb, deep vein thrombosis than pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis alone (relative risk, 0.93; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.60-1.44). Although this study was published after the “2018 ASH VTE guideline on thromboprophylaxis for hospitalized and nonhospitalized medical patients,”3 the results of trial did not change the recommendation, which suggests “pharmacological VTE prophylaxis alone over mechanical VTE prophylaxis combined with pharmacological VTE prophylaxis (conditional recommendation, very low certainty in the evidence of effects).”

Direct oral anticoagulants for thromboprophylaxis in medical patients (recommendation 13)

In the MARINER trial, 10 mg of rivaroxaban was given to medical patients classified to be at high risk of VTE for 45 days after hospital discharge.5 Thromboprophylaxis with rivaroxaban was not associated with a significantly lower risk of symptomatic VTE and death (hazard ratio [HR], 0.76; 95% CI, 0.52-1.09) due to VTE, as compared with placebo. Furthermore, the risk of clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding was increased (HR 1.66; 95% CI, 1.17-2.35) when compared with that with placebo. Although this study was published after the 2018 ASH VTE guideline,3 the results do not change the recommendation for inpatient thromboprophylaxis without extended VTE prophylaxis after hospital discharge for medical patients who are at high risk (strong recommendation,\ and moderate certainty in the evidence of effects).

Several publications were found, which included subgroup analyses of the APEX,6 MAGELLAN,7 and MARINER5 trials. The majority of the studies analyzed specific populations, such as older adult patients,8,9 patients with impaired renal function,10 and those with an increased risk of VTE and low risk of bleeding.11 Although these analyses do not change the 2018 ASH Guideline, patients who are appropriately risk stratified could be a target population for future RCTs on thromboprophylaxis in hospitalized medical patients after discharge.

Thromboprophylaxis in patients who are chronically ill or those in nursing home (recommendation 15)

Since the publication of the original guideline, we did not identify any RCTs or SRs in medical patients who were nonhospitalized, chronically ill or those who were in nursing home that change the current recommendations. In patients with cancer and COVID-19, the management and prevention of VTE have been addressed in specific ASH VTE guidelines.12,13 Specific guidelines for VTE prevention could be considered in other selected populations, such as patients with obesity14 or those with chronic kidney disease requiring or not requiring dialysis.15

Conclusions

The purpose of the 2018 VTE guideline on VTE prophylaxis for medical patients who were hospitalized and those who were not hospitalized was to provide evidence-based recommendations for prevention of VTE for medical patients. An extensive literature search was carried out to monitor and update the guideline. Although we found newly published studies on the subject, we judged that none of them should change the 19 recommendations from the 2018 ASH VTE guideline.

We suggest continuous monitoring of the guideline. Moreover, we suggest that future updates should include questions on the prevention of VTE in special populations, such as the older adult patients, patients with obesity, and those with renal and liver dysfunction.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: N.A.Z. receives research funding from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA and is a chairperson of the Mentored Research Award Committee for the Hemostasis and Thrombosis Research Society. N.A.Z. and S.M.R. serve as associate editors for Research and Practice of Thrombosis and Haemostasis (a journal supported by the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis); K.A.B. declares no competing financial interests.

Acknowledgments

Contribution: S.M.R. wrote the paper; and N.A.Z. and K.A.B. revised and made relevant contributions to the final manuscript.

References

- 1.American Society of Hematology https://www.hematology.org/education/clinicians/guidelines-and-quality-care/clinical-practice-guidelines/venous-thromboembolism-guidelines

- 2.Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust. The National Academy Press. Institute of Medicine; 2011. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/13058/clinical-practice-guidelines-we-can-trust [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schünemann HJ, Cushman M, Burnett AE, et al. American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: prophylaxis for hospitalized and nonhospitalized medical patients. Blood Adv. 2018;2(22):3198–3225. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2018022954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arabi YM, Al-Hameed F, Burns KEA, et al. Adjunctive intermittent pneumatic compression for venous thromboprophylaxis. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(14):1305–1315. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1816150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spyropoulos AC, Ageno W, Albers GW, et al. Rivaroxaban for thromboprophylaxis after hospitalization for medical illness. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(12):1118–1127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1805090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen AT, Harrington RA, Goldhaber SZ, et al. Extended thromboprophylaxis with betrixaban in acutely Ill medical patients. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(6):534–544. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1601747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen AT, Spiro TE, Büller HR, et al. Rivaroxaban for thromboprophylaxis in acutely ill medical patients. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(6):513–523. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1111096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ageno W, Lopes RD, Goldin M, et al. Rivaroxaban for extended thromboprophylaxis in acutely ill medical patients 75 years of age or older. J Thromb Haemost. 2021;19(11):2772–2780. doi: 10.1111/jth.15477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ageno W, Lopes RD, Yee MK, et al. Net-clinical benefit of extended prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism with betrixaban in medically ill patients aged 80 or more. J Thromb Haemost. 2019;17(12):2089–2098. doi: 10.1111/jth.14600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weitz JI, Raskob GE, Spyropoulos AC, et al. Thromboprophylaxis with rivaroxaban in acutely Ill medical patients with renal impairment: insights from the MAGELLAN and MARINER Trials. Thromb Haemost. 2020;120(3):515–524. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1701009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raskob GE, Ageno W, Albers G, et al. Benefit-risk assessment of rivaroxaban for extended thromboprophylaxis after hospitalization for medical illness. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022;11(20) doi: 10.1161/JAHA.122.026229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lyman GH, Carrier M, Ay C, et al. American Society of Hematology 2021 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: prevention and treatment in patients with cancer. Blood Adv. 2021;5(4):927–974. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020003442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cuker A, Tseng EK, Nieuwlaat R, et al. American Society of Hematology living guidelines on the use of anticoagulation for thromboprophylaxis in patients with COVID-19: January 2022 update on the use of therapeutic-intensity anticoagulation in acutely ill patients. Blood Adv. 2022;6(17):4915–4923. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2022007561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ceccato D, Di Vincenzo A, Pagano C, Pesavento R, Prandoni P, Vettor R. Weight-adjusted versus fixed dose heparin thromboprophylaxis in hospitalized obese patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Intern Med. 2021;88:73–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2021.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pai M, Adhikari NKJ, Ostermann M, et al. Low-molecular-weight heparin venous thromboprophylaxis in critically ill patients with renal dysfunction: a subgroup analysis of the PROTECT trial. PLoS One. 2018;13(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]