Abstract

Exposure to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) news pandemic is inevitable. This study aimed to explore the association between exposure to COVID-19 news on social media and feeling of anxiety, fear, and potential opportunities for behavioral change among Iranians. A telephone-based survey was carried out in 2020. Adults aged 18 years and above were randomly selected. A self-designed questionnaire was administered to collect information on demographic variables and questions to address exposure to news and psychological and behavioral responses regarding COVID-19. A multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to assess the relationship between anxiety, fear, behavioral responses, and independent variables, including exposure to news. In all, 1563 adults participated in the study. The mean age of respondents was 39.17 ± 13.5 years. Almost 55% of participants reported moderate to high-level anxiety, while fear of being affected by COVID-19 was reported 54.1%. Overall 88% reported that they had changed their behaviors to some extent. Exposure to the COVID-19 news on social media was the most influencing variable on anxiety (OR 2.21, 95% CI 1.62–3.04; P < 0.0001), fear (OR 1.95, 95% CI 1.49–2.56; P < 0.0001), and change in health behaviors (OR 2.02, 95% CI 1.28–3.19; P = 0.003) in the regression model. The fear of being infected by the COVID19 was associated with the female gender and some socioeconomic characteristics. Although exposure to the COVID-19 news on social media seemed to be associated with excess anxiety and fear, it also, to some extent, had positively changed people’s health behaviors towards preventive measures.

Subject terms: Psychology, Human behaviour

Introduction

The outbreak of COVID-19 had a detrimental effect on global healthcare systems with a rapid and profound impact on every aspect of human life1, from the way people socialize to work, live, shop, and plan for the future2. In addition to the virus's global spread, another sort of pandemic developed where misleading rumors and disinformation were shared through online media, including all the influential social media and platforms such as Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, and YouTube3. As such WHO warned all nations to not use fake information and avoid being contaminated with unfounded speculations on potential causes and cures of the disease. It was believed that sharing wrong information might have several side-effects including causing confusion, leading to risky behaviors, not following the evidence-based recommendations, and imposing psychological distress4. A well-known newspaper used the following title: ‘Coronavirus misinformation is dangerous. Think before you share’4. However, social media users, are less likely to fact-check information before sharing it5 and help to creating ‘infodemic’. The same story was evident during the COVID-19 pandemic and apparently even they used more social media and shared information due to isolation and quarantine6,7 and to receive updates about the current COVID-19 situation8.

Infodemic is defined as: ‘an overabundance of information—some accurate and some not—that makes it hard for people to find trustworthy sources and reliable guidance when they need it’9. It can intensify or lengthen the duration of pandemic10, and could threaten national and global efforts to control the disease outbreaks11.

It is well-documented that COVID-19 related misinformation increased psychological disorders among social media users12–15, which is a common response to any stressful situation16. The most common psychological consequences of pandemic related exposure to COVID-19 news on social media include anxiety disorders, depression17, and fear18. A meta-analysis of 14 cross-sectional studies indicated that spending an excessive amount of time on social media platforms was associated to a higher likelihood of experiencing symptoms of anxiety and depression19.

On the other hand, the responsible use of social media was reported to be associated with positive influence public awareness about the pandemic and protection against COVID-1920. Social media could provide users with valuable information, find solutions to problems such as uncertainties, managing crises, and help to improve emotional functioning and protect mental health20,21. Therefore, social networks have both positive and negative effects as a double-edged sword22. For instance, a higher level of fear may turn into panic, becoming dangerous and increasing harm and damage, although a certain degree of manageable fear can induce people to protect themselves and follow the measures established by states23.

To understand the appropriate use of social media during the COVID-19 pandemic, we must know about the consequences of exposure to social media on people’s health. A number of studies explored psychological15,19,24–26 and behavioral27–29 outcome as common and important measures. However, to the best of our knowledge, no previous study on the topic was reported from Iran. Thus, this study aimed to investigate the psychological and behavioral consequences of exposure to Covid-19 news on social media among Iranian adult population.

Methods

Design and participants

The present study was a telephone-based cross-sectional survey conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic in April 2020. At that time, the statistics for new COVID-19 cases were accumulating. For instance, according to the world metric records, there were about 47,593 new cases and 138 deaths in Iran on the first of April. During this period, Iran had several difficulties providing drugs and necessary supplies. However, participants were adults aged 18 and over, Iranian nationality, ability to speak in Persian, user of at least one social media platform, and experience of exposure to COVID-19 news on social media. No other restrictions were implemented. The study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration.

Sample size

The sample size was based on the following formula:

Considering Z = 1.96, P = 0.5 (assuming 50% would use social media), and d = 3% (precision), a sample size of 1067 participants was estimated. Considering the design effect of 1.5, recruiting a sample of 1600 was thought. However, in practice 1563 adults were included in the study.

Sampling

A sample of Iranian adults aged 18 years and above were randomly selected from the list of post codes and using their mobile phones (random digit-dial). All provinces in Iran were defined as the strata and proportional to the population density of each province the required sample size was estimated for the whole country. The primary sampling unit consisted of individuals living in a given province.

Measures

A self-designed questionnaire in Persian language consisting of two sections was administered. The items were developed based on study objectives. The first section was about socio-demographic information included the recording of age, gender, marital status, education, economic status, and occupation.

The second part of questionnaire was developed based on literature review7,29–32 and expert opinion. This part contained three sections (Table 1):

Exposure to news on the COVID-19 pandemic with three items including ‘to what extent do you follow the statistics and information on COVID-19?’, ‘to what extent do you follow formal news on COVID-19 released by the state?’ and ‘to what extent do you follow the news on COVID-19 on social media?’

Psychological response with two items related to anxiety and fear including ‘to what extent exposure to the news on COVID-19 made you feel anxious and worry?’, and ‘To what extent do you fear being infected with COVID-19?’

Behavioral response with one item ‘to what extent fear of being infected provoked you to stick to healthy behavior (hand washing, wearing face mask, social distancing)?’

Table 1.

Exposure to news on the COVID-19 pandemic and psychological and behavioral responses.

| Not at all | Slightly | Moderately | Considerably | A great deal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure to news on the COVID-19 pandemic | |||||

| To what extent do you follow the statistics and information on COVID-19? | |||||

| To what extent do you follow formal news on COVID-19 released by the state? | |||||

| To what extent do you follow the news on COVID-19 on social media? | |||||

| Psychological response | |||||

| To what extent exposure to the news on COVID-19 made you feel anxious and worry? | |||||

| To what extent do you fear being infected with COVID-19? | |||||

| Behavioral response | |||||

| a. To what extent fear of being infected provoked you to stick to hand washing? | |||||

| b. To what extent fear of being infected provoked you to stick to wearing a face mask? | |||||

| c. To what extent fear of being infected provoked you to stick to social distancing? | |||||

Each item was rated on a 5-point Likert scale. The questionnaire was evaluated for content and face validity by seven experts (three health psychologists, two epidemiologists, and two journalists) and found to be satisfactory. The internal consistency for the questionnaire was about acceptable level (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.62).

At the begging of the phone interview, people were asked for consent. We informed the participant about the purpose of the study [exploring the association between exposure to COVID-19 news on social media and anxiety, fear, and compliance with healthy behavior]. We also explained that we are independent non-governmental research group and we are not involved with any treatment or vaccination processes. The participants were ensured about the anonymity, confidentiality and voluntary participant in the study. After they accepted to take part in the survey, Interviewers asked the questions one by one and filled in the demographic details and the six study questions. All interviewers were trained for this specific study to assure that ethical principles and consistency in data collection were considered.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to report the data including mean, standard deviation, frequencies, and percentages. To assess the association between dependent variables (anxiety, fear, and self-reported behavior change) and exposure to news on COVID-19 both univariate and multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed. As such response categories for both dependent and independent variables merged to provide two classifications as follows: not at all and slightly = No and moderately, considerably, and a great deal = Yes. The results were presented as odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals. All statistical analyses were performed using R software (ver. 3.6.3, College Station, Texas, USA).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol including obtaining informed consent due to the COVID-19 pandemic was approved by the ethic committee of the Iranian National Institute for Medical Research Development (IR.NIMAD.REC.1399.297). All participants were made aware of the study protocol, and informed consent was obtained.

Results

Participants

In all 1563 adults participated in the study. The mean age of participants was 39.17 ± 13.5 years. Most participants had secondary (60.1%) or higher education (35.3%), half of the sample were had intermediate economic status, while the vast majority of individuals were high school-educated adults (60.1%) and university or college-leveled institutes (35.3%). The description of sociodemographic variables is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Iranian adults who participated in the study (n = 1563).

| Variables | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (Mean ± SD) | 39.17 ± 13.5 |

| Gender | |

| Female | 775 (49.6) |

| Male | 788 (50.4) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 342 (21.9) |

| Married | 1160 (74.3) |

| Divorced/widowed | 61 (3.8) |

| Economic status (n = 1313) | |

| Poor | 322 (24.5) |

| Intermediate | 619 (47.2) |

| Good | 372 (28.3) |

| Education (n = 1013) | |

| Primary | 74 (4.7) |

| Secondary | 428 (27.3) |

| Higher | 511 (32.7) |

| Employment status (n = 1453) | |

| Unemployed | 64 (4.4) |

| Housewife | 516 (35.5) |

| Student | 95 (6.5) |

| Employed | 687 (47.3) |

| Retired | 91 (6.3) |

Descriptive findings

Moderate to high-level of anxiety was reported by 55.4% of participants and this was 54.1% for fear of being affected by coronavirus disease. Eighty-eight percent of people reported that they have changed their behaviors. The detailed results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics for the study measures.

| Not at all | Slightly | Moderately | Considerably | A great deal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | |

| To what extent do you follow the statistics and information on COVID-19? (n = 1559) | 70 (4.5) | 307 (19.7) | 342 (21.9) | 539 (34.6) | 301 (19.3) |

| To what extent do you follow formal news on COVID-19 released by the state? (n = 1560) | 153 (9.8) | 447 (28.7) | 306 (19.6) | 477 (30.6) | 177 (11.3) |

| To what extent do you follow the news on COVID-19 on social media? (n = 1561) | 517 (33.1) | 379 (24.3) | 204 (13.1) | 340 (21.8) | 121 (7.8) |

| To what extent exposure to the news on COVID-19 made you feel anxious and worry? (n = 1044) | 137 (13.1) | 328 (31.4) | 211 (20.2) | 261 (25.0) | 107 (10.2) |

| To what extent do you fear being infected with COVID-19? (n = 1561) | 375 (24.0) | 342 (21.9) | 268 (17.2) | 324 (20.8) | 252 (16.1) |

| To what extent fear of being infected provoked you to stick to healthy behaviors? (n = 1188) | 29 (2.4) | 113 (9.5) | 136 (11.4) | 504 (42.4) | 406 (34.2) |

Feeling of anxiety

In the multivariable logistic regression model, experience of anxiety significantly was associated with exposure to news on social media (OR 2.21, 95% CI 1.62–3.04; P < 0.0001). The results are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

The results obtained from logistic regression analysis for feeling anxiety.

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Age | 0.99 (0.98–1.01) | 0.68 | 0.99 (0.97–1.06) | 0.43 |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 1.0 (ref.) | 1.0 (ref.) | ||

| Male | 1.33 (1.03–1.69) | 0.024 | 1.44 (0.93–2.24) | 0.10 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 1.0 (ref.) | 1.0 (ref.) | ||

| Married | 1.05 (0.79–1.39) | 0.71 | 0.85 (0.54,1.34) | 0.48 |

| Divorced/widowed | 1.33 (0.62–2.85) | 0.46 | 1.32 (0.45–3.9) | 0.61 |

| Economic status | ||||

| Very good | 1.0 (ref.) | 1.0 (ref.) | ||

| Intermediate | 0.82 (0.61–1.1) | 0.18 | 0.94 (0.61–1.45) | 0.79 |

| Poor | 0.93 (0.83–0.36) | 0.66 | 0.95 (0.57–1.56) | 0.83 |

| Education | ||||

| Primary | 1.0 (ref.) | 1.0 (ref.) | ||

| Secondary | 0.27 (0.06–1.35) | 0.008 | 0.74 (0.36–1.55) | 0.42 |

| Higher | 0.25 (0.24,0.74) | 0.003 | 0.56 (0.26–1.21) | 0.14 |

| Employment status | ||||

| Unemployed | 1.0 (ref.) | 1.0 (ref.) | ||

| Housewife | 0.74 (0.41–1.36) | 0.34 | 0.77 (0.32–1.85) | 0.56 |

| Student | 1.15 (0.62–2.14) | 0.65 | 0.65 (0.25–1.72) | 0.56 |

| Employed | 0.73 (0.35–1.51) | 0.4 | 0.72 (0.33–1.57) | 0.41 |

| Retired | 0.43 (0.19–0.98) | 0.046 | 0.47 (0.15–1.4) | 0.18 |

| Exposure to information and statistics on COVID-19 | ||||

| No | 1.0 (ref.) | 1.0 (ref.) | ||

| Yes | 1.05 (0.75–1.45) | 0.78 | 0.94 (0.57,1.55) | 0.83 |

| Exposure to formal news about COVID-19 | ||||

| No | 1.0 (ref.) | 1.0 (ref.) | ||

| Yes | 1.4 (1.04–1.85) | 0.02 | 1.4 (0.98–2.1) | 0.059 |

| Exposure to COVID-19 news on social media | ||||

| No | 1.0 (ref.) | 1.0 (ref.) | ||

| Yes | 2.31 (1.78–2.98) | 0.0001 | 2.21 (1.62–3.04) | 0.0001 |

*Bold values are significant.

Feeling of fear

Being female (OR 2.17, 95% CI 1.46–3.22; p-value < 0.001), intermediate economic status (OR 0.73, 95% CI 0.51–0.99; p-value = 0.049), being employed (OR 2.05, 95% CI 1.01–6.22; p-value = 0.047), higher exposure to information and statistics on COVID-19 (OR 1.52, 95% CI 1.1–2.12; p-value = 0.011), exposure to formal news on COVID-19 (OR 1.62, 95% CI 1.20–2.20; p-value = 0.002) and exposure to social media for updating on the COVID-19 news (OR 1.95, 95% CI 1.49–2.56; p-value < 0.001) showed significant association with feeling of fear. The results are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

The results obtained from logistic regression analysis for feeling of fear.

| Characteristics | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Age | 0.99 (0.98–1.01) | 0.08 | 0.99 (0.98–1.05) | 0.25 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 1.0 (ref.) | 1.0 (ref.) | ||

| Female | 2.04 (1.67–2.5) | < 0.0001 | 2.17 (1.46–3.22) | < 0.0001 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 1.0 (ref.) | 1.0 (ref.) | ||

| Married | 1.14 (0.89–1.45) | 0.29 | 1.22 (0.82–3.83) | 0.32 |

| Divorced/widowed | 1.64 (0.94–2.9) | 0.08 | 1.79 (0.84–3.83) | 0.21 |

| Economic status | ||||

| Very good | 1.0 (ref.) | 1.0 (ref.) | ||

| Intermediate | 0.75 (0.57–0.99) | 0.042 | 0.73 (0.51–0.99) | 0.049 |

| Poor | 0.86 (0.63–1.62) | 0.32 | 0.89 (0.6–1.32) | 0.57 |

| Education | ||||

| Primary | (ref.) | 1.0 (ref.) | ||

| Secondary | 0.87 (0.65–1.16) | 0.33 | 0.9 (0.64–1.49) | 0.91 |

| Higher | 1.06 (0.79–1.42) | 0.69 | 1.02 (0.62–1.65) | 0.93 |

| Employment status | ||||

| Unemployed | 1.0 (ref.) | 1.0 (ref.) | ||

| Employed | 1.54 (0.92–2.61) | 0.1 | 2.05 (1.01–6.22) | 0.047 |

| Housewife | 2.56 (1.5–4.36) | 0.001 | 1.9 (0.88–4.13) | 0.10 |

| Student | 1.96 (1.03–3.75) | 0.04 | 1.76 (0.74–4.23) | 0.20 |

| Retired | 1.7 (0.89–3.27) | 0.11 | 2.2 (0.97–4.99) | 0.058 |

| Exposure to information and statistics on COVID-19 | ||||

| No | 1.0 (ref.) | 1.0 (ref.) | ||

| Yes | 1.66 (1.26–2.15) | 0.0001 | 1.52 (1.1–2.12) | 0.011 |

| Exposure to formal news about COVID-19 | ||||

| No | 1.0 (ref.) | 1.0 (ref.) | ||

| Yes | 1.86 (1.47–2.36) | 0.0001 | 1.62 (1.20–2.20) | 0.002 |

| Exposure to COVID-19 news on social media | ||||

| No | 1.0 (ref.) | 1.0 (ref.) | ||

| Yes | 2.003 (1.63–2.46) | 0.0001 | 1.95 (1.49–2.56) | < 0.0001 |

*Bold values are significant.

Self-reported behavioral responses

The only factor that influenced behavior change was exposure to the COVID-19 news on social media (OR 2.02, 95% CI 1.28–3.19; P = 0.003). In fact, people reported that they took more preventive measures (hand washing, wearing face mask, social distancing) after exposure to COVID-19 news on social media. The results are reported in Table 6.

Table 6.

The results obtained from logistic regression for self-reported behavior change.

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Age | 0.99 (0.98–1.01) | 0.44 | 0.99 (0.97–1.02) | 0.79 |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 1.0 (ref.) | 1.0 (ref.) | ||

| Male | 1.6 (1.12–2.28) | 0.009 | 1.86 (0.97–3.54) | 0.059 |

| Marriage status | ||||

| Single | 1.0 (ref.) | 1.0 (ref.) | ||

| Married | 1.19 (0.79–1.78) | 0.41 | 1.15 (0.6,2.20) | 0.67 |

| Divorced/widow | 1.24 (0.46–3.35) | 0.67 | 1.01 (0.26,3.82) | 0.98 |

| Economic status | ||||

| Very good | 1.0 (ref.) | 1.0 (ref.) | ||

| Intermediate | 0.78 (0.51–1.18) | 0.24 | 1.31 (0.78,2.41) | 0.26 |

| Poor | 0.49 (0.18–1.36) | 0.17 | 0.91 (0.48,1.68) | 0.75 |

| Education | ||||

| Primary | 1.0 (ref.) | 1.0 (ref.) | ||

| Secondary | 1.07 (0.64–1.8) | 0.77 | 0.74 (0.35,1.57) | 0.43 |

| Higher | 0.86 (0.59–1.7) | 0.97 | 0.68 (0.29,1.58) | 0.37 |

| Employment status | ||||

| Unemployed | 1.0 (ref.) | 1.0 (ref.) | ||

| Housewife | 2.39 (1.17–4.86) | 0.016 | 2.16 (0.69–6.7) | 0.18 |

| Student | 3.75 (1.79–7.86) | < 0.0001 | 2.12 (0.61–7.38) | 0.23 |

| Employed | 2.65 (1.04–6.75) | 0.04 | 2.44 (0.90–6.59) | 0.07 |

| Retired | 0.43 (0.69–4.6) | 0.23 | 1.26 (0.33–4.83) | 0.73 |

| Exposure to information and statistics on COVID-19 | ||||

| No | 1.0 (ref.) | 1.0 (ref.) | ||

| Yes | 1.4 (0.91–2.16) | 0.12 | 1.33 (0.79–2.558) | 0.28 |

| Exposure to formal news about COVID-19 | ||||

| No | 1.0 (ref.) | 1.0 (ref.) | ||

| Yes | 1.93 (1.32–2.82) | 0.01 | 1.44 (0.89–2.32) | 0.13 |

| Exposure to COVID-19 news on social media | ||||

| No | 1.0 (ref.) | 1.0 (ref.) | ||

| Yes | 2.11 (1.45–3.07) | 0.0001 | 2.02 (1.28–3.19) | 0.003 |

Discussion

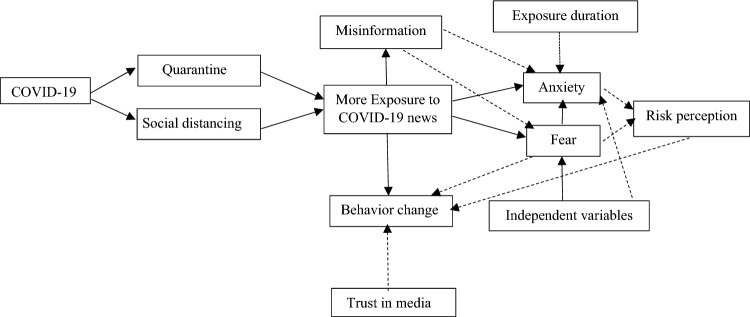

The media play a crucial role in response to crises by informing the public, making positive behavioral changes, and affecting mental health and well-being33. This study reported that exposure to the COVID-19 news on social media induced anxiety and fear, and also it showed some positive changes among participants. A schematic view of the mechanism of such observation is provided in (Fig. 1). This was proposed from the study findings, and from what one could find in the literature24,34,35.

Figure 1.

A schematic view of the mechanism of exposure to the COVID-19 news on social media.

Exposure to COVID-19 news

During the pandemic of COVID-19, people tend to use the social media more often36. Perhaps spending more time on social media during the COVID-19 pandemic could be due to two major reasons: quarantine and physical/social distancing (isolation, in-home lockdown, closure of services and public spaces, and loneliness)37. One might argue that these factors contributed to the increased use of social media. In addition, during pandemic social media was a major source for communication between families and friends. Even the use of social media for educational activity or office works contributed to extra use of the social media for news and views.

Anxiety

The finding showed that more exposure to the news on COVID-19 on social media was associated with greater anxiety. Evidence suggests that more access to information on social media could be stressful and induce more anxiety19,38,39. A study from Iran confirmed that online news played a critical role in COVID-19 anxiety40. A cross-sectional study conducted in China reported similar results, where more exposure to news on social media was significantly associated with greater anxiety7. Contrary to the majority published papers, a study conducted in Romania revealed that depression and anxiety were not associated with exposure to information regarding COVID-1941. Possible explanations for this may include differences in measures used or might be due t o cultural or socioeconomic differences. However, when individuals read the news and cannot do anything to prevent or reduce the risk of the disease, they begin to see themselves as vulnerable, and anxiety emerges. One other possible explanation is the fact that at the time the study commenced, the nature of COVID-19 was unknown, and thus it seemed a scary phenomenon and induced anxiety, fear and uncetainties. As such, one might argue that it is essential to see when and how psychological distress, including anxiety, depression, distress, or fear, is measured.

The current study did not assess the possible relationship between anxiety and exposure duration. Evidence suggests that more exposure to social media was associated with more psychological distress about the virus24. A study showed that more than four hours of using social media was related to a higher level of anxiety42. One argument is that more exposure to social media leads to more exposure to fake news and misinformation.

Fear

The current study showed that exposure to news on social media was related to higher levels of fear. This leads us to believe that social media exposure could be an indicator of even other negative emotions. Similar findings have been reported in other investigations in various settings15,25,26,43,44. For instance, a report from Hong Kong revealed that social media provoked fear in society45. The current study was conducted at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic when social media was full of negative news such as high daily statistics of the disease and deaths. Besides, social media users were facing a massive amount of information, where most of them did not have enough knowledge and health literacy to distinguish true information from fake news. Furthermore, usually, the governments also did not have an effective strategy to manage this situation. Thus, combining the above factors led to an increased fear among users. Experiencing fear and its association with positive preventive behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic has been reported previously in several studies15,36,44,46. Although the current study did not assess the possible relationship between fear and preventive behaviors, it seems that the implementation of educational interventions, including mass media campaigns such as ‘Together we will beat the covid-19’, might explain why people took preventive behaviors while they were frightened.

Psychological factors and independent variables

The current study did not show a significant relationship between most independent variables and anxiety. However, a study from Iran reported that anxiety was associated with female gender, younger age, and experience of the COVID-19 among family members or friends47. Similarly, a study reported that psychological factors were associated with being female, having cardiovascular diseases, smoking, and having a history of the COVID-19 symptoms, including fever, cough, and shortness of breath48. The role of independent variables in anxiety is undeniable.

We found that different factors, including female gender, intermediate economic status, being employed, following the COVID-19 statistics and formal news released by the state, and exposure to news on social media, had a significant relationship with fear. A study showed that COVID-19 has significantly affected people's fear due to incidents like economic slowdown, loss of jobs, losing loved ones, and so on49. Perhaps such observation also was true for the current study where due to economic sanction and some limitations for providing vaccine supply those who followed news on social media were more likely to experience ore fear as expected.

Behavioral responses

The findings showed that exposure to social media could positively influence health behaviors related to COVID-19 prevention. Similarly, some studies have demonstrated that frequent social media exposure regarding COVID-19 was associated with adopting preventive measures (e.g., face mask-wearing and handwashing)20,27,29. An online survey among American people showed that news monitoring was associated with greater social responsibility, more disinfecting, and greater caution about the severity of COVID-1950. It might be the result of the efforts of official departments to increase the public’s awareness of prevention strategies by providing updated information about COVID-19 on websites and social media51. According to behavioral models, exposure to social media increasing the users' awareness about how protecting themselves against COVI-19. Therefore, besides increases the perceived threat, it is a cue to action that encourages individuals to change their behaviors. So, the effect of social media on individuals’ protective behaviors can be influenced by different factors such as the type of information that users are exposed to, the level of the perceived threat, and the self-efficacy of individuals to copping the stress and manage the control of risk.

Exposure to COVID-19 misinformation

A number of social media users produce, release and transfer information that may lead to the dissemination of misinformation on social media52,53. So social media news often contains widespread misinformation, fake news and rumors54, that may cause many users psychological problems55. By analyzing the phenomenon of fake news in health, it was observed that false information could cause psychological disorders, panic, fear, depression, and fatigue14. For instance, one study showed that fear of COVID-19 and misunderstanding were associated with problematic social media usage, which led to direct or indirect psychological distress and insomnia13. Thus, the governments should consider the adverse consequence of misinformation during the COVID-19 pandemic on people's mental health47 and implment appropirate interventions. In such situations, the existence of the 'infodemics' team is necessary to deliver right information to the right people or a broader public audiences.

Risk perception

Risk perception is an important component of behavioral change56. According to the health behavioral models, information provides cues that influence perceptions regarding health threats35,57. According to the extended parallel process model (EPPM) as one of the relevant behavioral change models, individuals undergo two cognitive appraisals during exposure to a risky situation: the ability to respond to the recommended message (efficacy) and the perceived threat24. When the threat of COVID-19 is high and efficacy is low, people usually act to protect themselves from the fear rather than the danger itself58. A study showed that fear was positively associated with forming risk perceptions during an outbreak36,59,60. Individuals utilize psychological defense strategies to manage their fears in this situation57. A number of studies showed that when individuals obtain information from social media about COVID-19, they may perceive COVID-19 as a health threat and experience subsequent anxiety, depression, and fear61. Conversely, when perceived efficacy is high, people usually are motivated to protect themselves from danger and might follow the recommended massages58. In this regard, risk perception is related to adopting preventive behaviors such as social distancing and mask use36,60. Finding of a previous study revealed that self-efficacy was significantly associated with trust in government and media information on the pandemic7. Therefore, producing appropriate and reliable information would be necessary.

Strengths and limitations

Although the study benefited from a relatively good sample size and was selected based on a random sampling method, generalizing the findings might be challenging. This was a cross-sectional study in nature and thus could not indicate causality, and the findings should be interpreted with caution. People with mental health disorders might experience higher fear and anxiety regardless of social media exposure. Since we did not collected information in this regard, this should be considered as limitation. This study was conducted at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the anxiety, fear, and behavioral responses might have been influenced by the novelty and uncertainty of the situation rather than social media exposure pre se. Thus the findings should be interpreted with caution. We did not ask participants how much time they were spending on social media. Also, we did not explore ‘infodemic’ and how much did misinformation contributed to fear, anxiety, and behavioral responses. This could be a significant factor that study has missed. It is recommending that a such variable be investigated in future studies. Our study did not distinguish between social media platforms. Different platforms may induce different levels of fear, anxiety, and behavioral responses due to their varied ways of information dissemination, user demographics, and misinformation controls.

Conclusion

The findings demonstrated that exposure to the COVID-19 news on social media was associated with increased anxiety and fear. Yet, it might bring some positive behavioral changes. Therefore, improving people's media literacy in order to make them be able in identifying trusted information and share reliable content on social media seems necessary. Also, the governments should deal with 'infodemic' by providing timely up-to-dated and reliable information to prevent spread of misinformation. They are also responsible to introduce credible sources for reliable information.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all participants who made this study possible.

Author contributions

A.M. was the grant holder, designed the study, supervised the project, contributed to analysis and writing, and provided the final manuscript. S.M. contributed to analysis, sampling and writing process. P.M.H., H.Y. contributed to analysis and writing the first draft. M.R.B. helped in sampling, recruitment, and data collection. F.N.M., F.M. and M.T. helped in writing the proposal, administration of the project, and writing process. H.R. critically reviewed the paper and contributed to the writing. All authors read and approved the final draft.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Elite Researcher Grant Committee under award number (996382) from the National Institutes for Medical Research Development (NIMAD), Tehran, Iran.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Nicola M, Alsafi Z, Sohrabi C, Kerwan A, Al-Jabir A, Iosifidis C, et al. The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) Int. J. Surg. 2020;78:185–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee SA, Mathis AA, Jobe MC, Pappalardo EA. Clinically significant fear and anxiety of COVID-19: A psychometric examination of the Coronavirus Anxiety Scale. Psychiatry Res. 2020;290:113112. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boberg, S., Quandt, T., Schatto-Eckrodt, T. & Frischlich, L. Pandemic Populism: Facebook Pages of Alternative News Media and The Corona Crisis: A Computational Content Analysis. 10.48550/arXiv.2004.02566 (2020).

- 4.Phillips, T. Coronavirus misinformation is dangerous. Think before you share. The Guardian (2020).

- 5.Cuello-Garcia C, Pérez-Gaxiola G, van Amelsvoort L. Social media can have an impact on how we manage and investigate the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2020;127:198–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.06.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Depoux A, Martin S, Karafillakis E, Preet R, Wilder-Smith A, Larson H. The pandemic of social media panic travels faster than the COVID-19 outbreak. J. Travel Med. 2020;27(3):taaa031. doi: 10.1093/jtm/taaa031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gao J, Zheng P, Jia Y, Chen H, Mao Y, Chen S, et al. Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(4):e0231924. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pennycook G, McPhetres J, Zhang Y, Lu JG, Rand DG. Fighting COVID-19 misinformation on social media: Experimental evidence for a scalable accuracy-nudge intervention. Psychol. Sci. 2020;31(7):770–780. doi: 10.1177/0956797620939054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pan American Health Organization. Understanding Infodemic and Misinformation in the Fight Against COVID-19. Fact Sheet No. 5 (2020).

- 10.Mututwa W. COVID-19 infections on international celebrities: Self presentation and tweeting down pandemic awareness. J. Sci. Commun. 2020;19(5):A09. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mian A, Khan S. Coronavirus: The spread of misinformation. BMC Med. 2020;18:1–2. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01556-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verma G, Bhardwaj A, Aledavood T, De Choudhury M, Kumar S. Examining the impact of sharing COVID-19 misinformation online on mental health. Sci. Rep. 2022;12(1):8045. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-11488-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geldsetzer P. Knowledge and perceptions of COVID-19 among the general public in the United States and the United Kingdom: A cross-sectional online survey. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020;173(2):157–160. doi: 10.7326/M20-0912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shoib S, Buitrago JG, Shuja KH, Aqeel M, de Filippis R, Abbas J, et al. Suicidal behavior sociocultural factors in developing countries during COVID-19. L'encephale. 2022;48(1):78–82. doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2021.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rahman MA, Hoque N, Alif SM, Salehin M, Islam SMS, Banik B, et al. Factors associated with psychological distress, fear and coping strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia. Glob. Health. 2020;16:95. doi: 10.1186/s12992-020-00624-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395:912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stone LB, Veksler AE. Stop talking about it already! Co-ruminating and social media focused on COVID-19 was associated with heightened state anxiety, depressive symptoms, and perceived changes in health anxiety during Spring 2020. BMC Psychol. 2022;10(1):22. doi: 10.1186/s40359-022-00734-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Balkhi F, Nasir A, Zehra A, Riaz R. Psychological and behavioral response to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Cureus. 2020;12(5):e7923. doi: 10.7759/cureus.7923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee Y, Jeon YJ, Kang S, Shin JI, Jung YC, Jung SJ. Social media use and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in young adults: A meta-analysis of 14 cross-sectional studies. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):995. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-13409-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al-Dmour H, Masa’deh RE, Salman A, Abuhashesh M, Al-Dmour R. Influence of social media platforms on public health protection against the COVID-19 pandemic via the mediating effects of public health awareness and behavioral changes: Integrated model. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020;22(8):e19996. doi: 10.2196/19996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abbas J, Wang D, Su Z, Ziapour A. The role of social media in the advent of COVID-19 pandemic: Crisis management, mental health challenges and implications. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy. 2021;14:1917–32. doi: 10.2147/RMHP.S284313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li X, Guo X, Shi Z. Bright sides and dark sides: Unveiling the double-edged sword effects of social networks. Soc. Sci. Med. 2023;329:116035. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2023.116035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sandman PM. Crisis communication best practices: Some quibbles and additions. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 2006;34(3):257–262. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang YT, Li RT, Sun XJ, Peng M, Li X. Social media exposure, psychological distress, emotion regulation, and depression during the COVID-19 outbreak in community samples in China. Front. Psychiatry. 2021;12:644899. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.644899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abad A, da Silva JA, de Paiva Teixeira LEP, Antonelli-Ponti M, Bastos S, Mármora CHC, et al. Evaluation of fear and peritraumatic distress during COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil. Adv. Infect. Dis. 2020;10(3):184–194. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lelisho ME, Pandey D, Alemu BD, Pandey BK, Tareke SA. The negative impact of social media during COVID-19 pandemic. Trends Psychol. 2023;31(1):123–142. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yousuf H, Corbin J, Sweep G, Hofstra M, Scherder E, van Gorp E, et al. Association of a public health campaign about coronavirus disease 2019 promoted by news media and a social influencer with self-reported personal hygiene and physical distancing in the netherlands. JAMA Netw. Open. 2020;3(7):e2014323. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.14323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mesch GS, da Silva Neto WL, Storopoli JE. Media exposure and adoption of COVID-19 preventive behaviors in Brazil. Soc. Media Soc. 2022;2022:14614448221122203. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang SX, Graf-Vlachy L, Looi KH, Su R, Li J. Social media use as a predictor of handwashing during a pandemic: Evidence from COVID-19 in Malaysia. Epidemiol. Infect. 2020;148:e261. doi: 10.1017/S0950268820002575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hou F, Bi F, Jiao R, Luo D, Song K. Gender differences of depression and anxiety among social media users during the COVID-19 outbreak in China: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:11648. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09738-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yuen KF, Wang X, Ma F, Li KX. The psychological causes of panic buying following a health crisis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17(10):3513. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17103513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ahmed W, Vidal-Alaball J, Lopez Segui F, Moreno-Sánchez PA. A social network analysis of tweets related to masks during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17(21):8235. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17218235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jones R, Mougouei D, Evans SL. Understanding the emotional response to Covid-19 information in news and social media: A mental health perspective. Hum. Behav. Emerg. 2021;3(5):832–842. doi: 10.1002/hbe2.304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stuart J, O'Donnell K, O'Donnell A, Scott R, Barber B. Online social connection as a buffer of health anxiety and isolation during COVID-19. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2021;24(8):521–525. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2020.0645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Janz NK, Becker MH. The health belief model: A decade later. Health Educ. Q. 1984;11:1–47. doi: 10.1177/109019818401100101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zeballos Rivas DR, Lopez Jaldin ML, Nina Canaviri B, Portugal Escalante LF, Alanes Fernández AM, Aguilar Ticona JP. Social media exposure, risk perception, preventive behaviors and attitudes during the COVID-19 epidemic in La Paz, Bolivia: A cross sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(1):e0245859. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0245859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boursier V, Gioia F, Musetti A, Schimmenti A. Facing loneliness and anxiety during the COVID-19 isolation: The role of excessive social media use in a sample of Italian adults. Front. Psychiatry. 2020;11:586222. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.586222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cheng C, Jun H, Liang B. Psychological health diathesis assessment system: Anationwide survey of resilient trait scale for Chinese adults. Stud. Psychol. Behav. 2014;12:735–742. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Keles B, McCrae N, Grealish A. A systematic review: The influence of social media on depression, anxiety and psychological distress in adolescents. Int. J. Youth Adolesc. 2020;25:79–93. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shabahang R, Aruguete MS, McCutcheon LE. Online health information utilization and online news exposure as predictor of COVID-19 anxiety. North Am. J. Psychol. 2020;22(3):469–482. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cordos AA, Bolboacă SD. Lockdown, Social Media exposure regarding COVID-19 and the relation with self-assessment depression and anxiety. Is the medical staff different? Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2021;75(4):e13933. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.13933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hossain MT, Ahammed B, Chanda SK, Jahan N, Ela MZ, Islam MN. Social and electronic media exposure and generalized anxiety disorder among people during COVID-19 outbreak in Bangladesh: A preliminary observation. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(9):e0238974. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0238974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shigemura J, Ursano RJ, Morganstein JC, Kurosawa M, Benedek DM. Public responses to the novel 2019 coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in Japan: Mental health consequences and target populations. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2020;74(4):281–282. doi: 10.1111/pcn.12988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hetkamp M, Schweda A, Bäuerle A, Weismüller B, Kohler H, Musche V, et al. Sleep disturbances, fear, and generalized anxiety during the COVID-19 shut down phase in Germany: Relation to infection rates, deaths, and German stock index DAX. Sleep Med. 2020;75:350–353. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2020.08.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lin C-Y, Broström A, Griffiths MD, Pakpour AH. Investigating mediated effects of fear of COVID-19 and COVID-19 misunderstanding in the association between problematic social media use, psychological distress, and insomnia. Internet Interv. 2020;21:100345. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2020.100345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aslam F, Awan TM, Syed JH, Kashif A, Parveen M. Sentiments and emotions evoked by news headlines of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. Human. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2020;7:23. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moghanibashi-Mansourieh A. Assessing the anxiety level of Iranian general population during COVID-19 outbreak. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2020;51:102076. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ansari Ramandi MM, Yarmohammadi H, Beikmohammadi S, Hosseiny Fahimi BH, Amirabadizadeh A. Factors associated with the psychological status during the Coronavirus pandemic, baseline data from an Iranian province. Caspian J. Intern. Med. 2020;11(1):484–494. doi: 10.22088/cjim.11.0.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bhattacharya C, Chowdhury D, Ahmed N, Ozgür S, Bhattacharya B, Mridha SK, et al. The nature, cause and consequence of COVID-19 panic among social media users in India. Soc. Netw. Anal. Min. 2021;11:53. doi: 10.1007/s13278-021-00750-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Almutairi KM, Al Helih EM, Moussa M, Boshaiqah AE, Saleh Alajilan A, Vinluan JM, et al. Awareness, attitudes, and practices related to coronavirus pandemic among public in Saudi Arabia. Fam. Community Health. 2015;38(4):332–340. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0000000000000082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bao Y, Sun Y, Meng S, Shi J, Lu L. 2019-nCoV epidemic: Address mental health care to empower society. The Lancet. 2020;395(10224):e37–e38. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30309-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bontcheva, K., Gorrell, G. & Wessels, B. Social Media and Information Overload: Survey Results. arXiv preprint arXiv.2013:1306.0813.

- 53.Roth F, Bronnimann G. Focal Report 8: Risk Analysis Using the Internet for Public Risk Communication. ETH Zurich; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Meel P, Vishwakarma DK. Fake news, rumor, information pollution in social media and web: A contemporary survey of state-of-the-arts, challenges and opportunities. Expert Syst. Appl. 2020;153:112986. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gonzalez-Padilla DA, Tortolero-Blanco L. Social media influence in the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. Braz. J. Urol. 2020;46:120–124. doi: 10.1590/S1677-5538.IBJU.2020.S121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Napper LE, Fisher DG, Reynolds GL. Development of the perceived risk of HIV scale. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(4):1075–1083. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0003-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jahangiry L, Bakhtari F, Sohrabi Z, Reihani P, Samei S, Ponnet K, et al. Risk perception related to COVID-19 among the Iranian general population: An application of the extended parallel process model. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09681-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Witte K. Fear control and danger control: A test of the extended parallel process model (EPPM) Commun. Monogr. 1994;61(2):113–134. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Choi D-H, Yoo W, Noh G-Y, Park K. The impact of social media on risk perceptions during the MERS outbreak in South Korea. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017;72:422–431. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2017.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Oh SH, Lee SY, Han C. The effects of social media use on preventive behaviors during infectious disease outbreaks: The mediating role of self-relevant emotions and public risk perception. Health Commun. 2021;36(8):972–981. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2020.1724639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kramer AD, Guillory JE, Hancock JT. Experimental evidence of massive-scale emotional contagion through social networks. PNAS. 2014;111:8788–8790. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320040111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.