Abstract

Introduction

Bloodstream infections (BSI) caused by carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (CRAB) are associated with high mortality with limited treatment. The aim of this study is to compare effectiveness and safety of colistin-based versus cefiderocol-based therapies for CRAB-BSI.

Methods

This is a retrospective observational study enrolling patients with monomicrobial CRAB-BSIs treated with colistin or cefiderocol from 1 January 2020, to 31 December 2022. The 30-day all-cause mortality rate was the primary outcome. A Cox regression analysis was performed to identify factors independently associated with mortality. A propensity score analysis using inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) was also performed.

Results

Overall 118 patients were enrolled, 75 (63%) and 43 (37%) treated with colistin- and cefiderocol-based regimens. The median (q1–q3) age was 70 (62–79) years; 70 (59%) patients were men.

The 30-day all-cause mortality was 52%, significantly lower in the cefiderocol group (40% vs 59%, p = 0.045). By performing a Cox regression model, age (aHR = 1.03, 95% CI 1.00–1.05), septic shock (aHR = 1.93, 95% CI 1.05–3.53), and delayed targeted therapy (aHR = 2.42, 95% CI 1.11–5.25) were independent predictors of mortality, while cefiderocol-based therapy was protective (aHR = 0.49, 95% CI 0.25–0.93). The IPTW-adjusted Cox analysis confirmed the protective effect of cefiderocol (aHR = 0.53, 95% CI 0.27–0.98).

Conclusions

Cefiderocol may be a valuable treatment option for CRAB-BSI, especially in the current context of limited treatment options.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40121-023-00854-6.

Keywords: Antimicrobial resistance, Bloodstream infections, Carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii, Cefiderocol, Colistin

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out the study? |

| Carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii bloodstream infections (CRAB-BSI) are serious nosocomial infections associated with high mortality and healthcare costs. |

| Currently, treatment options available for CRAB-BSI are limited to a few antibiotics including high-dose sulbactam, colistin, and cefiderocol. |

| Cefiderocol may represent a valid alternative to colistin for the treatment of CRAB-BSI, but data are still limited. |

| What was learned from the study? |

| In this retrospective series of 118 patients with CRAB-BSI, cefiderocol was associated with a lower rate of mortality and adverse events than colistin. |

| Although the limited sample size did not allow a deeper analysis, combination therapy did not reduce mortality compared with monotherapy. |

| Emergence of in vivo cefiderocol resistance was rarely detected it this cohort: however, given its importance, future studies should investigate this issue. |

Introduction

Infections caused by carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (CRAB) are increasing worldwide [1]; in particular, according to data released in the last European Center for Disease Control (ECDC) report on antimicrobial resistance surveillance, the annual number of invasive isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii has tripled in the last 4 years in several countries (including Italy), and the proportion of carbapenem-resistant isolates to total isolates of Acinetobacter spp. surpassed 85% [1].

Importantly, CRAB infections are burdened by a significant risk of poor outcome: focusing on CRAB bloodstream infections, the 30-days infection-related mortality could reach the 30–50% of all cases, higher than that caused by carbapenem-susceptible strains [2, 3]. This can be partially explained by the underlying frailty of the patients infected by multidrug-resistant bacterial infections, often affected by multiple comorbidities, being immunocompromised, or having been exposed to prolonged antibiotic therapies; on the other hand, also the small antibiotic armamentarium available against these pathogens poses an increased risk of poor outcome [4].

In fact, despite its inclusion in 2017 WHO priority list as a “critical pathogen” for which new antibiotics are urgently needed [5], treatment options for severe CRAB infections remain limited.

To date, the available therapeutic options for severe CRAB infections are represented by ampicillin/sulbactam or colistin in monotherapy or in combo-therapy with other molecules (high-dose tigecycline, aminoglycosides, minocycline, high-dose meropenem) [6, 7]. However, as underlined in the current published guidelines [6, 7], evidence supporting the choice of the best therapeutic approach is not available.

In this context, cefiderocol, a new siderophore cephalosporin, showed remarkable in vitro activity against CRAB [8], representing a potential valid option against this pathogen.

Nevertheless, although early data emerging from “real-life” use are promising [9–11], current international guidelines [6, 7] suggest a “second-line” place in therapy of this new molecule for severe CRAB infections, since data of effectiveness deriving from current clinical trials are conflicting [12, 13].

Hence, the aim of this study was to compare the effectiveness and safety of cefiderocol-based regimens versus colistin-based ones in patients with CRAB bloodstream infection.

In particular, the primary objective of the study was to evaluate the 30-day all-cause mortality of the study population and compare this outcome between the two groups of patients. Secondary objectives included the evaluation of 30-day infection-related mortality, incidence of severe adverse events to antibiotic therapy, 90-day all-cause mortality, 90-day recurrence of CRAB-BSI, and emergence of cefiderocol or colistin resistance after or during therapy.

Methods

Study Design and Inclusion Criteria

This was a comparative retrospective monocentric cohort study conducted at the University Hospital of the Polyclinic of Bari over 36 months, from 1 January 2020 to 31 December 2022.

All available information, including demographics and clinical, microbiological, and instrumental data, were anonymized and collected on an electronic database.

All consecutive adult (aged ≥ 18 years) patients who developed a BSI caused by carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii complex were screened.

The criteria for inclusion of the study were: (1) CRAB monomicrobial bacteremia (CRAB-BSI); (2) therapy based on cefiderocol or colistin; (3) acquisition of informed consent.

Exclusion criteria were: (1) patients died within 48 h from targeted treatment initiation or before receiving any effective therapy; (2) patients treated for < 48 h with cefiderocol or colistin; (3) patients with incomplete data; (4) concurrent infections in blood or in any other body site; (5) concurrent COVID-19; (6) patients treated with regimens not containing cefiderocol or colistin; (7) patients treated with both cefiderocol and colistin (in serial or in parallel).

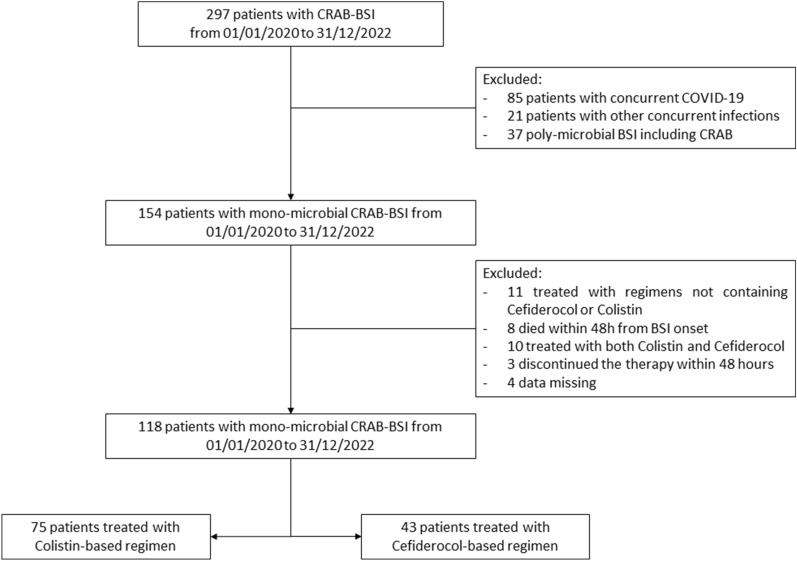

Figure 1 describes the flowchart of inclusion and exclusion of patients.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of inclusion and exclusion of patients

Study Endpoints

The primary endpoint of the study was evaluating the 30-day all-cause mortality.

Secondary outcomes of the study were:

Evaluating incidence of 30-day infection-related mortality.

Evaluating incidence of severe (grade 3–5) adverse events to antibiotic therapy (evaluated within 14 days of discontinuation).

Ninety-day all-cause mortality and 90-day CRAB-BSI recurrence.

Emergence of cefiderocol or colistin resistance after of during therapy.

Infection-related mortality was determined by an adjudication committee of at least two independent infectious disease specialists (DFB, AB, LD, RP, FDG, NDG) and was considered infection related if the death was caused by the direct complications of infection (e.g., septic shock, acute respiratory failure, or following infection control surgery) or in case of persistent signs of infection (ongoing fever, persistent positive blood cultures, leukocytosis, elevated CRP) at the time of death. Contrarily, a non-infection-related mortality was adjudicated if patients had died from a definite other cause that was independent from the CRAB-BSI. Mortality events that did not clearly fit the definitions of infection related or non-infection related were discussed within the committee and with the study research supervisors (AS, SG, LD) and attributed according to the most probable cause.

Patients were followed until discharge or until the day of death. In case of discharge before day 30 after infection onset, mortality was evaluated using information from hospital records which were linked with a municipal records database. Our hospital information system allows us access to patient personal data (living or deceased status, date of death). Therefore, we have no patients lost to follow-up in mortality analyses.

Sampling Process and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

According to current guidelines and hospital protocols, blood cultures were performed for all patients by collecting 20–30 ml blood per culture set before starting an empirical antimicrobial therapy. Two bottles (for aerobic and anaerobic bacteria culture, respectively) were collected for each set and immediately placed into a BACT/ALERT® 3D instrument (Biomerieux Inc., France). Positive aerobic blood cultures were subcultured on MacConkey agar, CNA blood agar, Sabouraud dextrose agar, mannitol-salt agar, and chocolate agar and incubated aerobically at 37 °C for 24 h.

Identification and antibacterial phenotypic susceptibility were tested on either the automated VITEK 2 system or VITEK MS (Biomerieux) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The interpretative breakpoints of MIC values were based on the criteria of the European committee on antimicrobial susceptibility testing (EUCAST).

Colistin susceptibility testing was made by broth microdilution. Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values were interpreted according to clinical breakpoints established by the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST). Cefiderocol susceptibility testing was made by disk diffusion method using 30-μg cefiderocol discs (Liofilchem®, Italy) in standard Mueller-Hinton agar plates. Inhibition zone diameters > 17 mm for cefiderocol corresponded to MIC values below the PK/PD breakpoint of sensitivity < 2 mg/l.

Statistical Analysis

All data were anonymized and collected on an electronic database.

Descriptive statistics were produced for demographic, clinical, and laboratory characteristics of patients. Medians and interquartile ranges (q1–q3) were produced for continuous variables, and numbers and percentages were produced for categorical variables.

For analysis purposes, patients were divided into two groups according to backbone antibiotic therapy (colistin or cefiderocol) or outcome (survived and non-survived to infection).

Since this was not a randomized controlled trial, the sample size was not pre-determined. However, after data retrieving and initial descriptive statistics needed for data cleaning, a full assessment of statistical power and sample size was performed to evaluate whether the study reached adequate statistical soundness.

The sample size analysis was as follows.

Considering a potential mortality rate associated with CRAB-BSI of 40–50%, we determined that a sample size of at least 40 patients per arm reached ≥ 80% power in case of a mortality rate difference of at least 20% (considered clinically significant) with an alpha (type I error) of 0.05.

The distribution of outcomes, clinical findings, and laboratory findings between groups was analyzed with univariate parametric and nonparametric tests, with Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney U tests (where appropriate) for continuous variables and with Pearson's χ2 test (Fisher's exact test where appropriate) for categorical variables, according to data distribution.

To assess predictors of 30-day all-cause mortality, a univariate Cox regression model was produced for variables of interest. Then, a stepwise multivariable Cox regression was applied to control for potential confounders and was adjusted for associated variables (p < 0.1) with endpoints on univariate analysis or considered significant according to the current literature.

Additionally, Kaplan-Meier curve estimates were also performed for variables of interest.

Finally, an inverse-probability treatment-weighted (IPTW) adjusted analysis was applied to compare the impact of colistin and cefiderocol on risk of 30-day all-cause mortality after balancing the cohort for variables influencing treatment assignment. The analysis was performed using the treatment effects module implemented in Stata 16.1 Special Edition.

Hence, the final analysis was balanced in terms of variables influencing assignment to treatment as follows: each patient’s probability of receiving cefiderocol or colistin was determined through a non-parsimonious multivariable logistic regression model (Supplementary Table 1) constructed to estimate each patient’s probability of receiving the drug (i.e., the propensity score) [14].

Stabilized weights (Supplementary Table 2), based on the inverse of the propensity score, were then applied to generate a weighted cohort in which covariate distributions were independent of treatment assignment [15]

Standardized differences were examined to assess balance using a threshold of 10% to indicate clinically meaningful imbalance requiring further adjustment in outcome analyses [15].

The weighted propensity score distributions were visually inspected, and an overidentification test for covariate balance was performed to ensure that the final model and all covariates were balanced between groups, to allow valid comparisons. Similarly, treatment group was conditioned on covariates that were not optimally balanced after IPTW (standardized difference ≥ 10%).

Finally, the IPTW-adjusted Cox regression was computed by taking the average of the difference between the observed and potential outcomes for each patient.

In all cases, p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using STATA “Special Edition,” version 16.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Ethics

This study was performed with the formal approval of the Ethics Committee of University Hospital-Polyclinic of Bari (study number: 6527) and in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and national and institutional standards. Data were previously pseudo-anonymized, according to the requirements set by Italian data protection code (leg. decree 196/2003) and European general data protection regulation (GDPR 2016/679). The patients provided written informed consent (available from the corresponding author) for use of their data for research purposes.

Results

General Characteristics of the Study Population and CRAB-BSI

A total of 297 patients with CRAB-BSI were screened in the study period, as described in Fig. 1.

One hundred seventy-nine patients were excluded, and 118 were included in the final analysis: of them, 75 and 43 were treated with colistin- and cefiderocol-based regimens, respectively.

The median (q1–q3) age was 70 (62–79) years, with 70 (59%) patients being men, with a median Charlson comorbidity index of 6 (4–8). The most frequent comorbidity was chronic kidney failure (42%), followed by type II diabetes (36%) and chronic heart diseases (25%).

Overall, 67 (57%) patients were hospitalized in a medical ward, 31 (26%) in ICU, and 20 (17%) in a surgical unit. CRAB-BSI occurred with septic shock, acute lung failure, and acute kidney failure in 36%, 42%, and 31% of patients, respectively. At presentation, the median SOFA score was 5 (2–6), and 30 (25%) patients had a PITT bacteriemia score > 4.

All CRAB isolates were sensitive to colistin [median (q1–q3) MIC = 0.5 (0.5–1) mg/l] and to cefiderocol [median (q1–q3) disk diffusion diameter 20 (18–22) mm], except two strains which were resistant to cefiderocol at baseline. Of note, all the strains were resistant to aminoglycosides, carbapenems, fluoroquinolones, and ampicillin/sulbactam; finally, tigecycline sensitivity (MIC ≤ 2 mg/l) was documented in 11 (9%) cases.

Description of Antibiotic Therapies and Comparison of Patients Treated with Colistin and Cefiderocol

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients treated with a colistin- or cefiderocol-based regimen were compared and are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical features of patients treated with colistin- and cefiderocol-based regimens

| Overall (n. 118) | Colistin-based regimens (n. 75) | Cefiderocol-based regimens (n. 43) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (q1–q3) age, years | 70 (62–79) | 71 (62–78) | 69 (60–81) | 0.917 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 70 (59) | 44 (59) | 26 (60) | 0.848 |

| Previous COVID-19 infection, n (%) | 30 (25) | 18 (24) | 12 (28) | 0.639 |

| Median (q1–q3) Charlson comorbidity index | 6 (4–8) | 6 (4–7) | 6 (4–8) | 0.712 |

| Severe immunocompromised state, n (%) | 21 (18) | 14 (19) | 7 (16) | 0.744 |

| Characteristics of infection, n (%) | ||||

| Fever (TC > 38 °C) | 76 (64) | 43 (57) | 33 (77) | 0.034 |

| Septic shock | 42 (36) | 27 (36) | 15 (35) | 0.903 |

| Acute lung failure | 49 (42) | 35 (47) | 14 (33) | 0.134 |

| Acute kidney failure | 36 (31) | 24 (32) | 12 (28) | 0.642 |

| Ward of evaluation, n (%) | ||||

| Medical ward | 67 (57) | 46 (61) | 21 (49) | 0.391 |

| Surgical ward | 20 (17) | 12 (16) | 8 (19) | |

| Intensive care unit | 31 (26) | 17 (23) | 14 (33) | |

| Median (q1–q3) SOFA score at onset | 5 (2–6) | 5 (2–7) | 4 (2–6) | 0.245 |

| PITT bacteriemia score > 4, n (%) | 30 (25) | 20 (27) | 10 (23) | 0.682 |

| Site of infection treated with surgical source control, n (%) | 26 (22) | 23 (31) | 3 (7) | 0.003 |

| Site of infection, n (%) | ||||

| Primary BSI or urinary tract | 37 (31) | 21 (28) | 16 (37) | 0.154 |

| CVC-related | 36 (31) | 25 (33) | 11 (26) | |

| Intra-abdominal | 19 (16) | 16 (21) | 3 (7) | |

| Lung | 12 (10) | 5 (7) | 7 (16) | |

| Skin and soft tissue | 12 (10) | 6 (8) | 6 (14) | |

| Endovascular | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | |

| Osteoarticular | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | |

| Monotherapy, n (%) | 19 (16) | 3 (4) | 16 (37) | < 0.001 |

| Combination with other antibiotics, n (%) | 99 (84) | 72 (96) | 27 (63) | |

| Ampicillin/sulbactam | 35 (30) | 25 (33) | 10 (23) | 0.249 |

| Fosfomycin | 42 (36) | 22 (29) | 20 (47) | 0.061 |

| Tigecycline | 37 (31) | 37 (49) | 0 | < 0.001 |

| Combinations of more than 2 drugs | 48 (41) | 48 (64) | 0 | < 0.001 |

| Time to targeted antibiotic therapy, n (%) | ||||

| Within 24 h from infection onset | 32 (27) | 16 (21) | 16 (37) | 0.036 |

| From 24 to 72 h from infection onset | 48 (41) | 29 (39) | 19 (44) | |

| After 72 h from infection onset | 38 (32) | 30 (30) | 8 (19) | |

| Adverse events to antimicrobial therapy, n (%) | 13 (11) | 12 (16) | 1 (2) | 0.022 |

| Median (q1–q3) duration of antibiotic therapy | 11 (8–16) | 13 (8–18) | 10 (9–13) | 0.017 |

| 30-day all-cause mortality, n (%) | 61 (52) | 44 (59) | 17 (40) | 0.045 |

| 30-day infection related mortality, n (%) | 55 (47) | 42 (56) | 13 (30) | 0.007 |

| 90-day infection recurrence/relapse, n (%) | 8 (7) | 4 (5) | 4 (9) | 0.409 |

| 90-day all-cause mortality, n (%) | 67 (58) | 48 (64) | 19 (42) | 0.032 |

q1–q3 first–third quartile, BSI bloodstream infection, CVC central venous catheter

Boldface means statistically significant (p < 0.05)

The two groups were comparable in terms of age, sex, Charlson comorbidity index, hospitalization ward, and characteristics of the bloodstream infection at the onset, including presentation with septic shock, acute respiratory or kidney failure, and median SOFA score (5 versus 4, respectively, p = 0.245).

Nevertheless, some important differences emerged. At first, compared with cefiderocol, colistin was used less frequently in monotherapy (37% versus 4% respectively, p < 0.001); in particular, colistin was associated with > 2 drugs in 48 patients (66%), especially tigecycline (51%) or ampicillin/sulbactam (35%). On the other hand, for combination therapy, the preferred companion drug to cefiderocol was fosfomycin (74%), followed by ampicillin/sulbactam (37%); in addition, three cases of cefiderocol plus fosfomycin plus ampicillin/sulbactam were recorded. None of the patients in the cefiderocol group was treated with tigecycline or with > 2 companion antibiotics. Another difference was the higher incidence of BSI in patients, which required surgical source control in the colistin group (31% versus 7%, p = 0.003).

Importantly, time to targeted antimicrobial therapy administration was dissimilar between the two groups (p = 0.036). In detail, in the colistin group, only 21% of patients received targeted therapy within 24 h of infection onset and 30% received it after > 72 h. In the cefiderocol group, 37% received targeted antibiotic therapy within 24 h of onset of infection and 19% after 72 h.

Interestingly, the incidence of adverse events because of antibiotic therapy was higher for colistin (p = 0.022): 1 (2%) patient treated with cefiderocol developed an allergic skin rash, while 12 (16%) patients treated with colistin developed a grade 3–4 adverse event, including 10 cases of acute kidney injury and 2 cases of peripheral neuropathy. In addition, two patients (5%) developed resistance to cefiderocol (both in the monotherapy group) after treatment, while no resistance to colistin was detected.

Finally, a shorter median duration of therapy was noticed in the cefiderocol versus colistin group (10 versus 13 days respectively, p = 0.017).

Of note, 7% (8 cases) of patients experienced a CRAB-BSI relapse/recurrence within 90 days, without significant difference in incidence between the two groups (5% versus 9% for colistin- versus cefiderocol-based regimens, respectively, p = 0.409).

Analysis of 30-Day Mortality

Fifty-two percent (61 of 118) and 47% (55 of 118) of 30-day all-cause and infection-related mortality were registered in the whole population, respectively.

The clinical and demographic characteristics of patients who survived and experienced 30-day all-cause mortality are summarized in Table 2 (in Supplementary Table 3 the analysis of 30-day infection-related mortality is given).

Table 2.

Comparison of clinical characteristics of patients who survived or died after CRAB BSI

| Overall (n. 118) | Clinical cure (n. 57) | 30-day all-cause mortality (n. 61) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (q1–q3) age, years | 70 (62–79) | 69 (58–75) | 74 (66–82) | 0.008 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 70 (59) | 36 (63) | 34 (56) | 0.412 |

| Previous COVID-19 infection, n (%) | 30 (25) | 15 (26) | 15 (25) | 0.830 |

| Median (q1–q3) Charlson comorbidity index | 6 (4–8) | 5 (3–7) | 6 (5–8) | 0.004 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| Cardiovascular diseases | 29 (25) | 12 (21) | 17 (28) | 0.390 |

| Type II diabetes | 42 (36) | 20 (35) | 22 (36) | 0.912 |

| Chronic kidney failure (eGFR < 60 ml/min) | 50 (42) | 18 (32) | 32 (52) | 0.022 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 25 (21) | 9 (16) | 16 (26) | 0.165 |

| Obesity (BMI > 30 kg/m2) | 24 (20) | 9 (16) | 15 (25) | 0.235 |

| Solid neoplasia | 17 (14) | 8 (14) | 9 (15) | 0.912 |

| Hematologic neoplasia | 6 (5) | 0 (0) | 6 (10) | 0.015 |

| Severe immunocompromised state, n (%) | 21 (18) | 6 (11) | 15 (25) | 0.046 |

| Ward of evaluation, n (%) | ||||

| Medical ward | 67 (57) | 27 (47) | 40 (66) | 0.106 |

| Surgical ward | 20 (17) | 13 (23) | 7 (11) | |

| Intensive care unit | 31 (26) | 17 (30) | 14 (23) | |

| Characteristics of infection, n (%) | ||||

| Fever (TC > 38 °C) | 76 (64) | 37 (65) | 39 (64) | 0.912 |

| Septic shock | 42 (36) | 14 (25) | 28 (46) | 0.016 |

| Acute lung failure | 49 (42) | 20 (35) | 29 (48) | 0.170 |

| Acute kidney failure | 36 (31) | 14 (25) | 22 (36) | 0.175 |

| Median (q1–q3) SOFA score at onset | 5 (2–6) | 4 (2–6) | 5 (4–7) | 0.030 |

| PITT bacteriemia score > 4, n (%) | 30 (25) | 12 (21) | 18 (30) | 0.292 |

| Site of infection treated with surgical source control, n (%) | 26 (22) | 11 (19) | 15 (25) | 0.488 |

| Site of infection, n (%) | ||||

| Primary BSI or urinary tract | 37 (31) | 18 (32) | 19 (31) | 0.880 |

| CVC-related | 36 (31) | 17 (30) | 19 (31) | |

| Intra-abdominal | 19 (16) | 9 (16) | 10 (16) | |

| Lung | 12 (10) | 7 (13) | 5 (8) | |

| Skin and soft tissue | 12 (10) | 6 (11) | 6 (10) | |

| Endovascular | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (2) | |

| Osteoarticular | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (2) | |

| Time to targeted antibiotic therapy, n (%) | ||||

| Within 24 h from infection onset | 32 (27) | 21 (37) | 11 (18) | 0.032 |

| From 24 to 72 h from infection onset | 48 (41) | 23 (40) | 25 (40) | |

| After 72 h from infection onset | 38 (32) | 13 (23) | 25 (41) | |

| Definitive antibiotic therapy for BSI, n (%) | ||||

| Colistin-based | 75 (64) | 31 (54) | 44 (72) | 0.045 |

| Cefiderocol-based | 43 (36) | 26 (46) | 17 (28) | |

| Severe adverse events to antibiotic therapy, n (%) | 13 (11) | 7 (12) | 6 (10) | 0.672 |

| Median (q1–q3) duration of antibiotic therapy | 11 (8–16) | 12 (10–17) | 9 (6–14) | 0.005 |

| Median (q1–q3) days from symptom onset to discharge or death for infection | 17 (8–28) | 23 (16–45) | 9 (6–20) | < 0.001 |

q1–q3 first–third quartile, BSI bloodstream infection

Boldface means statistically significant (p < 0.05)

By considering the analysis of 30-day all-cause mortality and comparing the two groups, a higher median age (74 versus 69, p = 0.008), Charlson comorbidity index (6 versus 5, p = 0.004), SOFA score (5 versus 4, p = 0.030), incidence of septic shock (46% versus 25%, p = 0.016), and incidence of chronic renal failure (52% versus 32%, p = 0.022) were observed in patients who did not survive at day 30.

The 30-day all-cause mortality rate was different in the two groups: 59% (44/75) for the colistin group and 40% (17/43) for the cefiderocol one (p = 0.045); similarly, also 30-day infection-related mortality was lower in the cefiderocol group (30% versus 56%, p = 0.007, see Supplementary Table 2).

Moreover, a Cox regression univariate and multivariate analysis (Table 3) for predictors of 30-day infection-related mortality was conducted.

Table 3.

Univariable, multivariable, and IPTW-adjusted multivariable Cox model for 30-day all-cause mortality

| Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | IPTW-adjusted multivariable analysis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p value | aHR | 95% CI | p value | aHR | 95% CI | p value | |

| Age per 1 year increase | 1.03 | 1.00–1.05 | 0.005 | 1.03 | 1.00–1.05 | 0.035 | 1.03 | 0.99–1.06 | 0.097 |

| Male sex | 0.79 | 0.46–1.36 | 0.414 | – | |||||

| Previous COVID-19 | 1.04 | 0.77–1.41 | 0.773 | – | |||||

| Charlson comorbidity per 1 point increase | 1.17 | 1.05–1.31 | 0.003 | 1.09 | 0.96–1.24 | 0.161 | |||

| Severe immunocompromission | 1.53 | 0.82–2.86 | 0.179 | – | |||||

| Site of infection treated with surgical source control | 0.91 | 0.48–1.74 | 0.792 | – | |||||

| SOFA score per 1 point increase | 1.07 | 0.98–1.16 | 0.095 | – | |||||

| PITT bacteriemia score | 1.20 | 0.67–2.15 | 0.534 | – | |||||

| Septic shock at presentation | 1.82 | 1.06–3.11 | 0.028 | 1.93 | 1.05–3.53 | 0.033 | 2.81 | 1.35–5.84 | 0.005 |

| Acute kidney injury at presentation | 1.30 | 0.74–2.27 | 0.358 | – | |||||

| Acute respiratory failure at presentation | 1.49 | 0.87–2.54 | 0.142 | – | |||||

| Time to appropriate antimicrobial therapy | |||||||||

| Within 24 h from infection onset | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| From 24 to 72 h from infection onset | 1.61 | 0.75–3.42 | 0.216 | 1.64 | 0.75–3.59 | 0.210 | |||

| After 72 h from infection onset | 2.43 | 1.16–5.12 | 0.019 | 2.42 | 1.11–5.25 | 0.025 | |||

| Cefiderocol-based antibiotic therapy | 0.51 | 0.28–0.94 | 0.031 | 0.49 | 0.25–0.93 | 0.029 | 0.53 | 0.27–0.98 | 0.047 |

| Antibiotic therapy including sulbactam | 0.98 | 0.55–1.77 | 0.972 | – | |||||

| Antibiotic therapy including fosfomycin | 0.43 | 0.22–0.81 | 0.010 | – | |||||

| Antibiotic therapy including tigecycline | 1.65 | 0.95–2.85 | 0.070 | – | |||||

| Monotherapy vs combotherapy | 0.81 | 0.39–1.66 | 0.570 | – | |||||

IPTW inverse probability treatment weighting

Boldface means statistically significant (p < 0.05)

At univariable model, age (HR = 1.03, 95% CI 1.00–1.05), Charlson comorbidity index (HR = 1.17, 95% CI 1.05–1.31), septic shock (HR = 1.82, 95% CI 1.06–3.11), and delayed appropriate antimicrobial therapy (> 72 h from BSI onset) (HR = 2.43, 95% CI 1.16–5.12) were associated with increased mortality, while the use of a cefiderocol-based regimen (HR = 0.51, 95% CI 0.28–0.94) was protective.

Interestingly, the use of combination therapy was not associated with a significant reduction in 30-day infection-related mortality (HR = 0.81, 95% CI 0.39–1.66) compared to monotherapy; however, the presence of fosfomycin in case of combination regimens was associated with a reduced mortality (HR = 0.43, 95% CI 0.22–0.81).

The multivariate analysis confirmed that the independent risk factors for 30-day infection-related mortality were age increase (aHR = 1.03, 95% CI 1.00–1.05), septic shock (aHR = 1.93, 95% CI 1.05–3.53), and delayed targeted therapy (> 72 h from the BSI onset: aHR = 2.42, 95% CI 1.11–5.25); contrarily, the use of cefiderocol-based antibiotic therapy was protective (aHR = 0.49, 95% CI 0.25–0.93).

Similar results were also obtained by performing similar analysis exploring predictors of 30-day infection-related morality (Supplementary Table 4).

The 90-day all-cause mortality was also explored in our population: overall, 67 (58%) of patients died within 90 days of infection onset (64% vs 42% in the colistin versus cefiderocol group, respectively, p = 0.032).

Propensity Score Adjusted Analysis of 30-Day Mortality

To better evaluate the impact of treatment with cefiderocol or colistin on 30-day mortality risk, the whole cohort was balanced with a propensity score analysis by applying an IPTW-adjusted model (see Methods section: Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Table 2).

The multivariable Cox regression analysis was than newly performed on the pseudo-population (Table 3) balanced for age, sex, time to appropriate antimicrobial therapy, BSI treated with surgical source control, and use of mono- or combo-therapy. The analysis confirmed that septic shock (aHR = 2.81, 95% CI 1.35–5.84) was associated with mortality, while cefiderocol-based therapy was an independent predictor of a better outcome (aHR = 0.53, 95% CI 0.27–0.98).

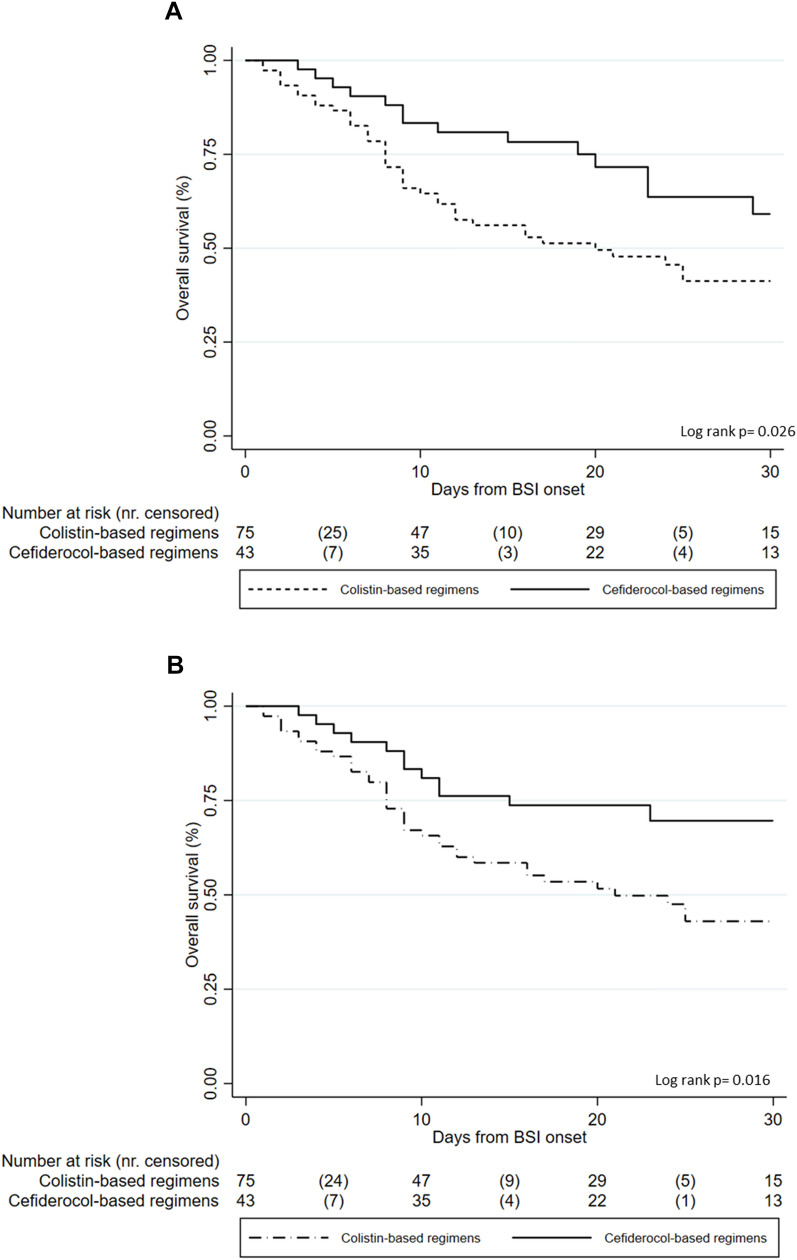

Finally, to graphically explore the association between the two types of regimens and mortality, Kaplan-Meier curves were made for 30-day all-cause mortality (Fig. 2a) and 30-day infection-related mortality (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves of 30-day all-cause mortality (a) and infection-related mortality (b)

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest observational study currently available designed to compare the all-cause and infection-related mortality of colistin- and cefiderocol-based regimens for monomicrobial CRAB-BSI.

Compared to colistin, an independent protective effect of cefiderocol on mortality risk was documented in this study, even after adjusting the survival model for patients’ probability of receiving cefiderocol or colistin (the propensity score). In fact, given the observational nature of the study and the non-randomized prescription of therapies, which was solely based on clinical judgment, an IPTW regression analysis was also performed to balance the study cohort and improve the robustness of analysis.

Although the results of the CREDIBLE trial [12] evidenced higher mortality in the cefiderocol treatment group than in the “best-available therapy” arm, data deriving from observational studies are in line with our work, suggesting a valuable place for cefiderocol in therapy for CRAB infections. To date, only three studies have directly compared cefiderocol-based therapies with other current treatment options for severe CRAB infections [9–11] with a sample size comparable to this study but a different design.

In particular, the study of Pascale et al. [9] included a multicentric cohort of 107 patients admitted to the ICU for severe COVID-19 who developed a CRAB infection (pneumonia or bloodstream infection) during the ICU stay. The study explored the 28-day all-cause mortality of patients treated with cefiderocol (used in monotherapy in 100% of cases) versus other regimens composed of different drugs. The mortality rate reached 57% and was probably influenced by concurrent severe COVID-19, which was the primary cause of admission of patients to the ICU: indeed, although cefiderocol was apparently protective in this study (although this was not statistically significant), the only independent predictor of mortality was the SOFA score, which was significantly higher in subjects who died at the end of follow-up (median SOFA: 10 versus 6 points).

Contrarily, the studies conducted by Falcone et al. [10] and Russo et al. [11] directly compared cefiderocol versus colistin and showed a significant beneficial effect of the new siderophore cephalosporin over the older drug. Of note, the study of Falcone et al. [10] is the largest work available and analyzed the outcome of 124 subjects (79 BSI and 35 VAP), identifying a mortality rate of 55.8% versus 35% in colistin versus cefiderocol group, respectively. However, in the subgroup analysis, the protective effect of cefiderocol was confirmed only in the BSI group. Importantly, in this study, cefiderocol and colistin were used in either mono- or combo-therapy, but the design and sample size were not suitable for exploring the impact of different combination therapies on mortality. In addition, despite the relevant sample size, some important limitations were noticed as stated by the authors, including several polymicrobial infections and cases of concurrent COVID-19 and CRAB infections.

Finally, the study of Russo et al. [11] was conducted on a sample of 73 VAPs with associated BSI caused by CRAB (54 and 19 in the colistin and cefiderocol group, respectively). Herein, the mortality difference between the two arms was significantly higher (14-day mortality = 5% versus 76% and 30-day mortality = 32% versus 98% in the cefiderocol and colistin arm, respectively) than mortality difference emerging from previous studies analyzed. In addition, in this study, cefiderocol was used in combination in 100% of cases; however, only the association with fosfomycin was significantly associated with a better outcome in both the unadjusted and IPTW-adjusted populations. Finally, it should be noted that several COVID-19 and polymicrobial infections were also included in this study.

Compared with the aforementioned works, our study presents some noticeable aspects of novelty. First, in this work only monomicrobial infections were included, limiting the known biasing effect of polymicrobial infections [16]. Second, only patients with documented BSI were included to minimize the risk of overestimating CRAB infections by including patients with only a colonization (for instance, in case of CRAB isolation from non-sterile samples) and minimize the potential biasing effect of inadequate penetration of cefiderocol or colistin in deep sites, including the lower respiratory tract [17].

Third, to exclude patients with additional mortality risk related to other infectious diseases, subjects with concurrent COVID-19 or other serious concomitant infections were not analyzed. Fourth, only subjects treated with colistin or cefiderocol as first-line therapy were included, strengthening the validity of the comparison. Last, in this study both “all-cause” and “infection-related” mortalities are separately presented: given the complexity of the “real-world” population of patients affected by CRAB-BSI, evaluating the real impact of infection on mortality is clinically meaningful especially compared with all-cause mortality. In this case, the two endpoints were almost overlapping, demonstrating the clinical significance of monomicrobial CRAB-BSI on risk of poor outcome of patients.

Interestingly, in our work, the use of mono- or combo-therapy was not associated with a different outcome; however, a protective effect of fosfomycin was noticed with the univariable Cox model. Conversely, the addition of sulbactam did not modify the outcome, and the use of tigecycline increased the mortality risk. Nevertheless, the sample size limits the possibility to draw conclusions on this topic: further powered studies should explore these data. In fact, one of the major areas of concern regarding cefiderocol monotherapy is the potential emergence of in vivo resistance in the course of therapy, which may be reduced by using combination therapies [18].

Additional risk factors for mortality emerging from this study were older age, septic shock, and delayed appropriate antimicrobial therapy, as frequently reported by other studies conducted on gram-negative bacterial BSI [2, 9–11, 19, 20]. Importantly, to improve the outcome of BSIs, many additional factors are determinant: for instance, a multi-step bundle approach to manage gram-negative bacterial BSI may be beneficial, improving the identification of deep sites of infections and rate of early targeted antimicrobial therapy and allowing rapid discontinuation of antibiotics in cases of uncomplicated BSIs, preventing adverse events [21].

Finally, by discussing secondary endpoints, it is interesting to notice the incidence of CRAB-BSI 90-day recurrence (7% of initial population) and 90-day all-cause mortality (58%) in our study. These results show the complexity of the “real-life” population experiencing BSI caused by multidrug-resistant organisms, often burdened by a high rate of mortality and infection relapse. Although this study was not primarily designed to evaluate these endpoints, their numerical relevance supports the need to further explore and investigate how to clarify the implications of BSI, from both a clinical and a methodological point of view [22].

Moreover, regarding secondary outcomes, it should be mentioned that the rate of adverse events to antibiotic therapy was significantly lower in the cefiderocol compared with colistin group: this reinforces the known safety profile of the drug [8], which is in line with other beta-lactams and cephalosporins.

To better read these data, some important limitations of the work should be acknowledged. First, the retrospective nature of the study and relatively small sample size may reduce the generalizability of results, although the sample size was sufficient to address the primary outcome of the study. Second, the decision to start cefiderocol or colistin-containing regimens was non-randomized but based on the physician’s decision. This could generate a so-called “channeling bias,” defined as the potential allocation of a certain drug in the groups of patients with possibly better prognoses. However, a propensity score analysis was performed to minimize this bias. Third, several patients received combination therapies with different antibiotics, including fosfomycin, ampicillin/sulbactam, and tigecycline; the impact of these therapies probably biased results, but the design of the study was not adequate to explore this point. Finally, all patients who received < 48 h of therapy or deceased within 48 h from treatment initiation were excluded from further analysis. Although this potentially introduces a selection bias, it also limits the risk of including patients who survived or died for causes different or independent from the BSI or the treatments administered, limiting in turn the risk of producing false statistical associations.

In conclusion, this work strengthens the hypothesis of a valuable role of cefiderocol for the therapy of CRAB-BSI, especially in the current context of limited treatment options. Further studies should confirm these findings and explore the other areas of uncertainties, including the role of mono- and combination therapies and the risk of in vivo emergence of resistance.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Davide Fiore Bavaro, Roberta Papagni, Lucia Diella, Alessandra Belati; methodology: Lidia Dalfino and Davide Fiore Bavaro.; formal analysis: Davide Fiore Bavaro; investigation: all Authors.; writing—original draft preparation, Davide Fiore Bavaro, Roberta Papagni, Lucia Diella, Alessandra Belati; writing—review and editing: all authors; supervision: Adriana Mosca, Maria Dell’Aera, Salvatore Grasso and Annalisa Saracino. Davide Fiore Bavaro, Roberta Papagni, Alessandra Belati, Lucia Diella, Antonio De Luca, Gaetano Brindicci, Nicolo De Gennaro, Francesco Di Gennaro, Federica Romanelli, Stefania Stolfa, Luigi Ronga, Adriana Mosca, Francesco Pomarico, Maria Dell’Aera, Monica Stufano, Lidia Dalfino, Salvatore Grasso and Annalisa Saracino.

Funding

Publication fees were supported by Informa pro Srl. No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article. The Rapid Service Fee was funded by the authors.

Medical Writing and Editorial Assistance

The authors did not receive any medical writing or editorial assistance for this article.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethical Approval

This study was performed with the formal approval by the Ethical Committee of University Hospital-Polyclinic of Bari (study number: 6527) and in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and national and institutional standards. Data were previously pseudo-anonymized, according to the requirements set by the Italian data protection code (leg. decree 196/2003) and European general data protection regulation (GDPR 2016/679). The patients provided written informed consent (available from the corresponding author) for the use of their data for research purposes.

Conflict of Interest

The lead author affirms that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported, that no important aspects of the study have been omitted, and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained. The manuscript was written by the lead/corresponding author, and the authors have no financial conflicts of interest to declare related to this work.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Davide Fiore Bavaro and Roberta Papagni equally contributed to this work.

References

- 1.Antimicrobial resistance surveillance in Europe 2023–2021 data. Stockholm: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control and World Health Organization; 2023. Cataloguing-in-Publication (CIP) data. CIP data are available at http://apps.who.int/iris. Accessed 28 May 2023.

- 2.Falcone M, Tiseo G, Carbonara S, Marino A, Di Caprio G, Carretta A, et al. Mortality attributable to bloodstream infections caused by different carbapenem-resistant gram negative bacilli: results from a nationwide study in Italy (ALARICO Network) Clin Infect Dis. 2023 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciad100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alrahmany D, Omar AF, Alreesi A, Harb G, Ghazi IM. Acinetobacter baumannii infection-related mortality in hospitalized patients: risk factors and potential targets for clinical and antimicrobial stewardship interventions. Antibiotics (Basel) 2022;11(8):1086. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics11081086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gu S, Xiong J, Peng S, Hu L, Zhu H, Xiao Y, et al. Assessment of effective antimicrobial regimens and mortality-related risk factors for bloodstream infections caused by carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Infect Drug Resist. 2023;16:2589–2600. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S408927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. WHO publishes list of bacteria for which new antibiotics are urgently needed. https://www.who.int/news/item/27-02-2017-who-publishes-list-of-bacteria-for-which-new-antibiotics-are-urgently-needed. Accessed 10 May 2023.

- 6.Paul M, Carrara E, Retamar P, Tängdén T, Bitterman R, Bonomo RA, et al. European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) guidelines for the treatment of infections caused by multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacilli (endorsed by European Society of Intensive Care Medicine) Clin Microbiol Infect. 2022;28(4):521–547. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2021.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pranita DT, Samuel LA, Robert AB, Amy JM, van David D, Cornelius JC, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America guidance on the treatment of AmpC β-lactamase-producing enterobacterales, carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii, and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. Infect Clin Infect Dis. 2021;74(12):2089–2114. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCreary EK, Heil EL, Tamma PD. New perspectives on antimicrobial agents: cefiderocol. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2021;65(8):e0217120. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02171-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pascale R, Pasquini Z, Bartoletti M, Caiazzo L, Fornaro G, Bussini L, et al. Cefiderocol treatment for carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii infection in the ICU during the COVID-19 pandemic: a multicentre cohort study. JAC Antimicrob Resist. 2021;3(4):dlab174. doi: 10.1093/jacamr/dlab174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Falcone M, Tiseo G, Leonildi A, Della Sala L, Vecchione A, Barnini S, et al. Cefiderocol-compared to colistin-based regimens for the treatment of severe infections caused by carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2022;66(5):e0214221. doi: 10.1128/aac.02142-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Russo A, Bruni A, Gullì S, Borrazzo C, Quirino A, Lionello R, et al. Efficacy of cefiderocol- vs colistin-containing regimen for treatment of bacteraemic ventilator-associated pneumonia caused by carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in patients with COVID-19. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2023;62(1):106825. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2023.106825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bassetti M, Echols R, Matsunaga Y, Ariyasu M, Dozi Y, Ferrer R, et al. Efficacy and safety of cefiderocol or best available therapy for the treatment of serious infections caused by carbapenem-resistant gram-negative bacteria (CREDIBLE-CR): a randomised, open-label, multicentre, pathogen-focused, descriptive, phase 3 trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21(2):226–240. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30796-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wunderink RG, Matsunaga Y, Ariyasu M, Clevenbergh P, Echols R, Kaye KS, et al. Cefiderocol versus high-dose, extended-infusion meropenem for the treatment of gram-negative nosocomial pneumonia (APEKS-NP): a randomised, double-blind, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21(2):213–225. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30731-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brookhart MA, Schneeweiss S, Rothman KJ, Glynn RJ, Avorn J, Stürmer T. Variable selection for propensity score models. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163:1149–1156. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Austin PC, Stuart EA. Moving towards best practice when using inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) using the propensity score to estimate causal treatment effects in observational studies. Stat Med. 2015;34:3661–3679. doi: 10.1002/sim.6607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karakonstantis S, Kritsotakis EI. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the proportion and associated mortality of polymicrobial (vs monomicrobial) pulmonary and bloodstream infections by Acinetobacter baumannii complex. Infection. 2021;49(6):1149–1161. doi: 10.1007/s15010-021-01663-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katsube T, Saisho Y, Shimada Y, Furuie H. Intrapulmonary pharmacokinetics of cefiderocol, a novel siderophore cephalosporin, in healthy adult subjects. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2019;74:1971–1974. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkz123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stracquadanio S, Bonomo C, Marino A, Bongiorno D, Privitera GF, Bivona DA, et al. Acinetobacter baumannii and cefiderocol, between cidality and adaptability. Microbiol Spectr. 2022;10(5):e0234722. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.02347-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dalfino L, Stufano M, Bavaro DF, Diella L, Belati A, Stolfa S, et al. Effectiveness of first-line therapy with old and novel antibiotics in ventilator-associated pneumonia caused by carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: a real life, prospective, observational, single-center study. Antibiotics (Basel) 2023;12(6):1048. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics12061048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Falcone M, Suardi LR, Tiseo G, Galfo V, Occhineri S, Verdenelli S, et al. Superinfections caused by carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: a multicentre observational study from Italy (CREVID Study) JAC Antimicrob Resist. 2022;4(3):dlac064. doi: 10.1093/jacamr/dlac064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bavaro DF, Diella L, Belati A, De Gennaro N, Fiordelisi D, Papagni R, et al. Impact of a multistep bundles intervention in the management and outcome of gram-negative bloodstream infections: a single-center, "proof-of-concept" study. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2022;9(10):4. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofac488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harris PNA, McNamara JF, Lye DC, Davis JS, Bernard L, Cheng AC, et al. Proposed primary endpoints for use in clinical trials that compare treatment options for bloodstream infection in adults: a consensus definition. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2017;23(8):533–541. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2016.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.