Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic remains a major health concern worldwide, and SARS-CoV-2 is continuously evolving. There is an urgent need to identify new antiviral drugs and develop novel therapeutic strategies. Combined use of newly authorized COVID-19 medicines including molnupiravir, nirmatrelvir and remdesivir, has been actively pursued. Mechanistically, nirmatrelvir inhibits SARS-CoV-2 replication by targeting the viral main protease (Mpro), a critical enzyme in the processing of the immediately translated coronavirus polyproteins for viral replication. Molnupiravir and remdesivir, on the other hand, inhibit SARS-CoV-2 replication by targeting RNA-dependent RNA-polymerase (RdRp), which is directly responsible for genome replication and production of subgenomic RNAs. Molnupiravir targets RdRp and induces severe viral RNA mutations (genome), commonly referred to as error catastrophe. Remdesivir, in contrast, targets RdRp and causes chain termination and arrests RNA synthesis of the viral genome. In addition, all three medicines undergo extensive metabolism with strong therapeutic significance. Molnupiravir is hydrolytically activated by carboxylesterase-2 (CES2); nirmatrelvir is inactivated by cytochrome P450-based oxidation (e.g., CYP3A4); and remdesivir is hydrolytically activated by CES1 but covalently inhibits CES2. Additionally, remdesivir and nirmatrelvir are oxidized by the same CYP enzymes. The distinct mechanisms of action provide strong rationale for their combined use. On the other hand, these drugs undergo extensive metabolism that determines their therapeutic potential. This review discusses how metabolism pathways and enzymes involved should be carefully considered during their combined use for therapeutic synergy.

Keywords: Molnupiravir, nirmatrelvir, remdesivir, SARS-CoV-2, main protease, RNA-dependent RNA-polymerase

1. INTRODUCTION

Pandemics cause global disruptions to public health, financial system and even social stability tremendously. Throughout the human history, quite a few pandemics have been well documented [1–6] such as the smallpox pandemic of 1870–1874 and the ongoing HIV/AIDS pandemic starting in 1981 [7, 8]. It is estimated that the smallpox pandemic has killed between 300–500 million people [9–11], representing approximately 20% of the then world population. The ongoing HIV/AIDS pandemic is the longest in record and has lasted for over four decades with approximately 40 million people killed [7, 12, 13]. The current SARS-CoV-2 pandemic of 2019 (severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus-2), commonly referred to as COVID-19, was reported in December of 2019 [1]. As of today, the confirmed COVID-19 cases have reached the number of over 755 million with a total mortality of over 6.8 million worldwide [14].

COVID-19 symptoms manifest in a phase-specific manner: mild, pulmonary and hyperinflammatory [15–17]. These phases are interconnected in terms of viral replication and clinical manifestations. The mild phase is characterized by general malaise but lacks apparent respiratory changes [16]. The managing priority for patients in this phase is focused on prevention of spread (i.e., isolation), symptomatic management (e.g., fever reduction), monitoring of disease progression and antiviral therapy if needed. The pulmonary phase is characterized by sustained viral replication and pneumonia associated symptoms such as respiratory dysfunction (e.g., dyspnea) [18, 19]. Management of the pulmonary phase includes the use of antiviral therapy, anti-inflammatory agents, anticoagulants, or in combination [19]. The hyperinflammatory phase, directly associated with hospitalization and mortality, is manifested by acute respiratory distress syndrome and multi-organ failure [20–22]. Calming the cytokine storm with supplemental oxygen is a priority [23].

Immuno-prevention and -therapy are effective approaches to prevent and treat COVID-19 infection and progression. So far, all of the approved vaccines target the Spike protein, a surface protein of SARS-CoV-2 [24–26]. This viral protein initiates the cellular infection by interacting with the host receptor ACE2 (angiotensin-converting enzyme 2) and is an excellent target for vaccine development and immunotherapy [27–31]. Likewise, many immunotherapeutic COVID-19 agents target the Spike protein [29–31]. Etesevimab is a fully human monoclonal neutralizing antibody, binds specifically to SARS-CoV-2 and prevents its infection [32]. This monoclonal antibody is commonly used together with bamlanivimab, another monoclonal antibody [33]. The combination was authorized in December of 2021 for the treatment of mild and moderate COVID-19 in adults and children 12 or older. The Spike protein, on the other hand, is extensively glycosylated, undergoes conformational changes and exhibits great potential for rapid mutations [34–36]. These characteristics are linked to waning immunity against COVID-19, as shown by breakthrough infection and multiple surges [37–39].

The success in developing COVID-19 vaccines and antibody-based therapy, in such a short period of time, represents a significant stride in the scientific community and for the public health [40, 41]. The efforts of developing COVID-19 therapeutics, like those for vaccine development, are unprecedented as well [42, 43]. In a short span of two years, more than dozens of therapeutic targets have been identified [42–47], and hundreds of clinical trials have been completed or are ongoing [48]. These targets represent a comprehensive list from viral targets such as RNA-dependent RNA-polymerase (RdRp) to host proteins such as TMPRSS2 (transmembrane protease, serine 2). TMPRSS2 is a facilitator of SARS-CoV-2 infection [42, 43]. Many existing antiviral drugs have been shown to exert inhibitory activities against SARS-CoV-2 [49]. Lopinavir, a popular antiviral agent against HIV, has been reported to inhibit SARS-CoV-2 at an IC50 of 12 μM [50]. Favipiravir, an anti-influenza viral agent, inhibits SARS-CoV-2 at an IC50 of 9.6 μM [51]. The IC50 values (half-maximal inhibitory concentration) for both drugs are within their peak plasma concentrations [51]. On the other hand, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has authorized the use of several small molecule drugs specific to COVID-19 therapy including: molnupiravir, nirmatrelvir and remdesivir.

2. THERAPEUTIC CHARACTERISTICS OF MOLNUPIRAVIR, NIRMATRELVIR AND REMDESIVIR

Remdesivir received emergency use authorization from the FDA in May of 2020, and the full approval in October of the same year [52]. Molnupiravir and nirmatrelvir both received emergency use authorization a year later [53]. Nirmatrelvir is functionally derived from and developed based on lufotrelvir, a phosphate prodrug of a hydroxyketone that was designed to target SARS-CoV-2 [54]. However, nirmatrelvir but not lufotrelvir is orally active [55]. In contrast, both molnupiravir and remdesivir were developed originally to treat other viral infections. Remdesivir was intended initially for hepatitis C and later for Ebola [56]. Molnupiravir, along with its parent compound EIDD-1931, was intended initially to treat Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus and later human influenza virus [57]. While all three drugs have been approved for the treatment of COVID-19, they differ markedly in various aspects including viral targets, metabolism and pharmacokinetic determinations.

2–1. Mechanism of action

These small molecule COVID-19 drugs were approved in a timeframe of less than two years. This is unprecedented as new medicines typically take as many as ten years or even longer to get final approvals [58]. Excitingly these COVID-19 drugs differ in mechanism of action, suggesting combined use for additive or even synergistic activity. Mechanistically, nirmatrelvir inhibits SARS-CoV-2 replication by targeting the viral main protease (Mpro) [59]. This protease hydrolytically processes the immediately translated coronavirus polyproteins for assembling the viral replication complex [59]. The inhibition of nirmatrelvir toward Mpro is achieved by covalently interacting with the thiol group of catalytic cysteine-145 (Cys145) to form a thioimidate adduct [59, 60]. Crystallographic study has suggested that the covalent link for the thioimidate adduct is reversible [59]. In support of this possibility, dilution of Mpro - nirmatrelvir complexes by 100-fold led to a recovery of enzymatic activity [60]. Covalent-reversible inhibitors, compared with their covalent-irreversible counterparts, have several advantages, notably avoidance of producing new antigenic epitopes.

In contrast to nirmatrelvir, molnupiravir and remdesivir inhibit SARS-CoV-2 replication by targeting viral RdRp (Table 1) [61, 62]. However, molnupiravir and remdesivir lead to different outcomes. Remdesivir causes RdRp to pause or induces chain termination, whereas molnupiravir causes RdRp to introduce widespread errors of the viral genome, leading to lethal mutagenesis (Table 1). The incorporation efficiency of natural nucleotides over that of NHC-TP (tri-phosphorylated N-hydroxycytidine), the therapeutic metabolite of molnupiravir, into model RNA substrates follows the order GTP (12,841) > ATP (424) > UTP (171) > CTP (30), indicating that NHC-TP competes predominantly with CTP for incorporation (Table 1) [63]. Importantly, 3CLpro and RdRp, compared with the Spike protein, are more conserved [64–67]. For example, the Omicron isolates have only two missense mutations across the replicase-transcriptase complex [64]. RdRp, the core protein of the complex, has only a single mutation (i.e., P323L) [64]. This mutation is not in the RNA binding site and may not cause significant changes catalytically [64]. Likewise, Mpro exhibits high sequence and structural conservation [65], although some mutations have been identified [66].

Table 1.

Pharmacological characteristics

2–2. Clinical characteristics

In addition to mechanism of action, these COVID-19 drugs differ in several major clinical characteristics (Table 2). Molnupiravir is authorized for use in patients at 18 years of age or older; nirmatrelvir in patients at 12 years of age or older; and remdesivir in patients as young as 28 days old [68]. Both molnupiravir and nirmatrelvir are administered orally [69], whereas remdesivir is given through intravenous infusion [70]. Molnupiravir and nirmatrelvir are given twice a day but molnupiravir must be given 12 h apart. Molnupiravir and remdesivir are packaged singly, whereas nirmatrelvir is packaged along with the boosting agent ritonavir. The co-package is commonly referred as Paxlovid [71, 72]. With an exception of remdesivir, neither molnupiravir nor nirmatrelvir is authorized for use longer than 5 consecutive days or for initiation of treatment in patients requiring hospitalization due to severe COVID-19 [71, 72].

Table 2.

Efficacy and safety of molnupiravir, nirmatrelvir and remdesivir

| Characteristics | Molnupiravir | Nirmatrelvir | Remdesivir |

|---|---|---|---|

| Combined recipe | No | Yes | No |

| Dosing regimens | 800 mg/twice/12 h* | 300 mg/twice/day* | 100 mg/day* |

| Administrative route | Oral | Oral | Intravenous |

| Adults; children ages 12 years and older | Yes | ||

| Adults and children (28 days of age) | Yes | ||

| Adults | Yes | ||

| Over placebo in hospitalization/death | 6.77 over 9.72%a | 0.77 over 6.41%b | |

| Days to recovery (Treatment/control) | 0.73/1.10c | ||

| Over placebo in serious adverse events | 7.18 over 11.41%a | 6.68 over 16.14%b | 0.69–0.78c |

Fact sheet for healthcare providers: Emergency use of authorization for lagevrio™ (molnupiravir) capsules. Revised EUA Authorized Date: 08/2022; Fact sheet for healthcare providers: Emergency use of authorization for Paxlovid™. Original EUA Authorized Date: 12/2021. Veklury FDA Approval History (https://www.drugs.com/history/veklury.html).

[73];

[74];

Clinical trials have shown the superiority of all three medicines over placebo controls. As summarized in Table 2, the risk of hospitalization for all-cause mortality is 6.77% in the molnupiravir group, whereas the risk increases to 9.72% in the corresponding placebo group [73]. The relative risk of nirmatrelvir over placebo groups is more drastic: 0.77 versus 6.41% [74]. Similar trends are observed in regard to serious adverse events with a ratio of 0.63 (7.18/11.41%) for molnupiravir (treatment over placebo), 0.41 (6.68/16.14%) for nirmatrelvir and 0.69–0.78 for remdesivir, respectively (Table 2) [73, 75–77]. The serious adverse events vary depending on a medication. Compared to the placebo, the molnupiravir group has a higher incidence of bacterial pneumonia, nausea and dizziness [73], and the nirmatrelvir group has a higher incidence of dysgeusia, diarrhea, elevated alanine aminotransferase, headache, creatinine clearance, nausea and vomiting [74]. The remdesivir groups from multiple clinical trials have a wide range of serious adverse events from cardiovascular events, to pulmonary disorders, and to hepatic dysfunction [36, 75–79].

2–3. Broad spectrum of activities against SARS-CoV-2 variants

Molnupiravir, nirmatrelvir and remdesivir target Mpro or RdRp, which are sequence- and/or even structurally conserved compared to the Spike protein [65]. It is therefore anticipated that these medicines are effective against SARS-CoV-2 variants. Since the start of the pandemic, the SARS-CoV-2 virus has mutated over time, producing variants (e.g., Delta) and even subvariants (e.g., Omicron B1 and B2) [80]. Currently, Omicron subvariants are the dominant circulating SARS-CoV-2 [81, 82]. As summarized in Table 3, all three drugs remain effective against variants/subvariants based on both cytopathogenic reduction and viral replication assays [83–86]. Newly emerged variants are generally more sensitive than earlier variants to these drugs. For example, Omicron B1 is almost twice as sensitive as alpha variant based on the cytopathogenic reduction with the former having an EC50 value of 1.9 (half maximal effective concentration), whereas the latter is 3.6 μM. A similar ratio of sensitivity between these two variants occurs with nirmatrelvir and remdesivir (Table 3). It should be noted that these COVID-19 drugs, molnupiravir and remdesivir in particular, have been shown to exert inhibitory effects towards other viruses. For example, molnupiravir has been shown to potently inhibit the replication of influenza virus, a member of the family Orthomyxoviridae [87]. Likewise, members of the family Filoviridae are highly sensitive towards remdesivir with an EC50 value of as low as 3 nM, 10 or more times of the sensitivity of SARS-CoV-2, a member of the family Coronaviridae [36, 86].

Table 3.

| Drug/metabolite | Alpha | Beta | Gamma | Delta | Omicron B1 | Omicron B2 | GHB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molnupiravir | 3.6a | 1.9a | 3.9a | ||||

| NHC | 2.3a, 0.34b | 1.5a | 2.0a, 0.24b | 3.3a, 0.29b | 0.34b | 0.46b | 2.2a |

| Nirmatrelvir | 0.28a, 1.78 b | 0.14a | 0.28a, 1.65b | 0.21a, 1.80b | 0.14a | 1.9b | 0.11a |

| Remdesivir | 0.077a | 0.063a | 0.074a | 0.048a | 0.05a | ||

| GS-441524 | 0.76a | 0.77a | 0.90a | 0.87a | 0.50a | 0.81a |

3. METABOLISM AND ACTIVE TRANSPORT

Molnupiravir, nirmatrelvir and remdesivir, undergo extensive metabolism [36, 89–96], primarily through hydrolysis, oxidation or both (Table 4). All three drugs undergo hydrolysis, whereas nirmatrelvir and remdesivir also undergo oxidation. Hydrolysis of molnupiravir and remdesivir represents therapeutic activation, whereas both oxidation and hydrolysis of nirmatrelvir represents inactivation. On the other hand, metabolism is inherently linked to active transporters across cell membranes [97, 98]. Molnupiravir and remdesivir’s hydrolytic metabolites are negatively charged, thus requiring drug transporters for membrane translocation.

Table 4.

Metabolism pathways

| Pathway | Molnupiravir | Nirmatrelvir | Remdesivir |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrolysis | Yes | Yes* | Yes |

| Oxidation | Yes | Yes | |

| Significance (hydrolysis) | Activation | Activation | |

| Significance (oxidation) | Inactivation | TBD |

Via bacteria in the gastrointestinal tract [96]. TBD: to be determined.

3–1. Metabolism of molnupiravir

Molnupiravir is an isopropylester and structurally belongs to a superfamily of nucleoside analogs (Fig. 1). Members of this superfamily are widely used for anticancer and antiviral therapies [99–101]. Like many nucleoside drugs, molnupiravir is initially hydrolyzed to NHC and subsequently undergoes phosphorylation to form triphosphate. It is the triphosphate metabolite that targets RdRp and exerts potent antiviral activity [102]. Carboxylesterases constitute a large class of serine hydrolases with high catalytic efficiency. In humans, CES1 and CES2 are two carboxylesterases with known pharmacological and toxicological significance [103–106]. These two carboxylesterases, on the other hand, differ in their substrate specificity and tissue distribution [107–109]. CES1 preferably hydrolyzes esters with an acyl moiety relatively larger than its alkoxy moiety [93] and opposite is true with CES2 [104, 105].

Fig 1. Hydrolysis of molnupiravir by CES2.

Molnupiravir is a substrate of CES2 and the hydrolysis leads to the formation of N- hydroxycytidine. Boxed is the acyl moiety.

The isopropylester of molnupiravir has an alkoxy moiety relatively larger than its acyl moiety (boxed in Fig. 1). It is assumed to be hydrolyzed by CES2. Consistent with the assumption, hydrolysis of molnupiravir is correlated significantly with the expression of CES2 but not CES1, and the hydrolytic activity toward molnupiravir shows similarly to the tissue distribution of CES2 [95]. For example, kidney and intestine have abundant expression of CES2 and highly hydrolyze molnupiravir. The involvement of CES2 but not CES1 in the hydrolysis of molnupiravir is confirmed by recombinant enzymes [95]. Finally, several CES2 genetic polymorphic variants exhibit significantly altered activity toward molnupiravir. For example, the variants A178V and F485V have significantly decreased hydrolysis but the opposite is true with the variant R180H [95].

NHC, the hydrolytic metabolite of molnupiravir, undergoes three-step phosphorylation to produce monophosphate, diphosphate, and ultimately triphosphate, respectively. Potent antiviral activity is mainly driven by the triphosphate metabolite [36, 102]. The identities of kinases for the phosphorylation remain to be determined. Several kinases, such as adenylate kinase 2, pyruvate kinases and thymidine kinase 1, have nevertheless been implicated in such catalytic actions toward nucleoside analog drugs such as tenofovir [110]. These kinases have a broad tissue distribution, but a majority of them are expressed in cell- and organ-specific manner. The metabolic fate of these phosphorylated metabolites remains largely unknown. A recent study reports that NUDT18, a nucleoside diphosphate linked to moiety-X (NUDIX) hydrolase, has been shown to hydrolyze NHC triphosphate [111]. NUDIX hydrolases constitute a superfamily of hydrolases that known to play vital roles in energy metabolism and nutrition homeostasis [112].

3–2. Metabolism of nirmatrelvir

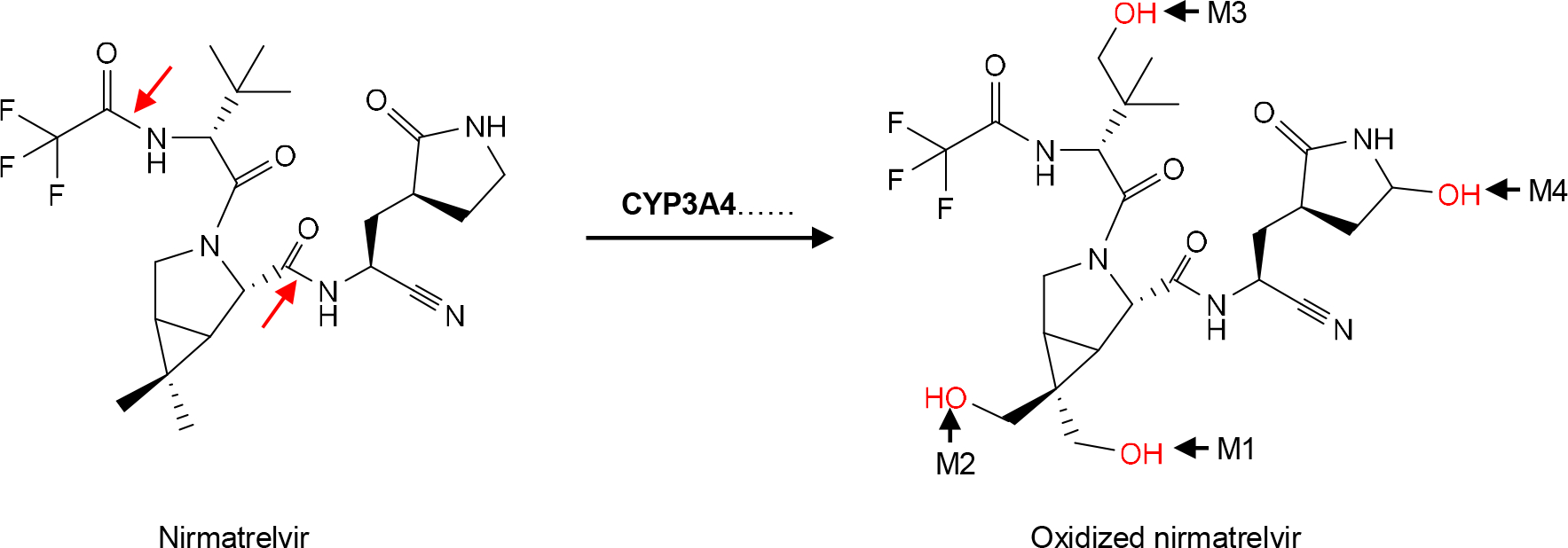

Nirmatrelvir is a fluorine-containing compound with a core-structure of azabicyclo hexane (Fig. 2). It has an oxopyrrolidin group, a cyano moiety and several amide bonds (Fig. 2). In vitro incubation of nirmatrelvir with liver microsomes, in the presence of NADPH, leads to degradation but the magnitude of the degradation is species-dependent [71]. Rat microsomes from both male and female produce a single major metabolite (M4). The peak corresponding to this metabolite is split into two, presumably eluted from interconverting diastereomers. In contrast, microsomes from human or monkey liver produce additional metabolites. In addition to M4, incubation with monkey microsomes results in two more metabolite peaks that have a retention time of 7.1 and 7.2 min, respectively [71]. Even with M4, the corresponding peak produced with monkey microsomes is wider and split into four. Finally, the peak area of the parent drug, upon incubation with monkey microsomes, is much smaller than that with rat microsomes, suggesting greater intrinsic clearance of nirmatrelvir in monkey liver.

Fig 2. Hydroxylation of nirmatrelvir.

The hydroxylation is catalyzed by several CYP enzymes, but primarily by CYP3A4. The hydroxylation (in Red) occurs at different atoms, resulting in the formation of M1, M2, M3 and M4, respectively. The red arrows indicate amide bonds for hydrolysis.

Human microsomes produce the most number of metabolites among these species, designated as M1, M2, M3 and M4, respectively. Metabolite M4 is shared by the incubation with both rat and monkey microsomes. M2 has a retention time of 7.2 min and is also present in the incubation with monkey microsomes [71]. M1, on the other hand, has a shortest retention time among all metabolites generated with microsomes from all three species. Human liver microsomes produce an additional metabolite M3, but this unique metabolite is minimal based on the peak area. Overall, the relative abundance among these metabolites is in the order of: M4>M2>M1>M3. Critically, the metabolite profile generated by human liver microsomes is almost identical to that generated by CYP3A4 [71]. Indeed, H-NMR spectra establish that all of these metabolites are produced by monohydroxylation in various positions such as the dimethyl 1–3 azabicyclo [3.1.0] hexane fused ring (Right of Fig. 2).

The dominant involvement of CYP3A4 in the metabolism of nirmatrelvir serves the foundation for this antiviral agent to be co-packaged with ritonavir (as Paxlovid), a strong CYP3A4 inhibitor and pharmacokinetic boosting agent [74]. Indeed, none of the metabolites generated by human liver microsomes are detected in participants who receive the co-package formulation, and the parent drug is the only drug entity in the plasma [96]. On the other hand, there are several notable metabolites present in urine and/or feces, designated as M5, M7, M8 and M9, respectively. M9 is present in the feces only, whereas M7 in the urine only. M5 and M8 are present in both urine and fecal samples [96]. M8 is generated through hydrolysis of the amide bond indicated by an arrow in red (Left of Fig. 2). M5 is also a hydrolytic metabolite through the cleavage of another amide bond as indicated by a red arrow. M5 is the precursor of M7, a glucuronide.

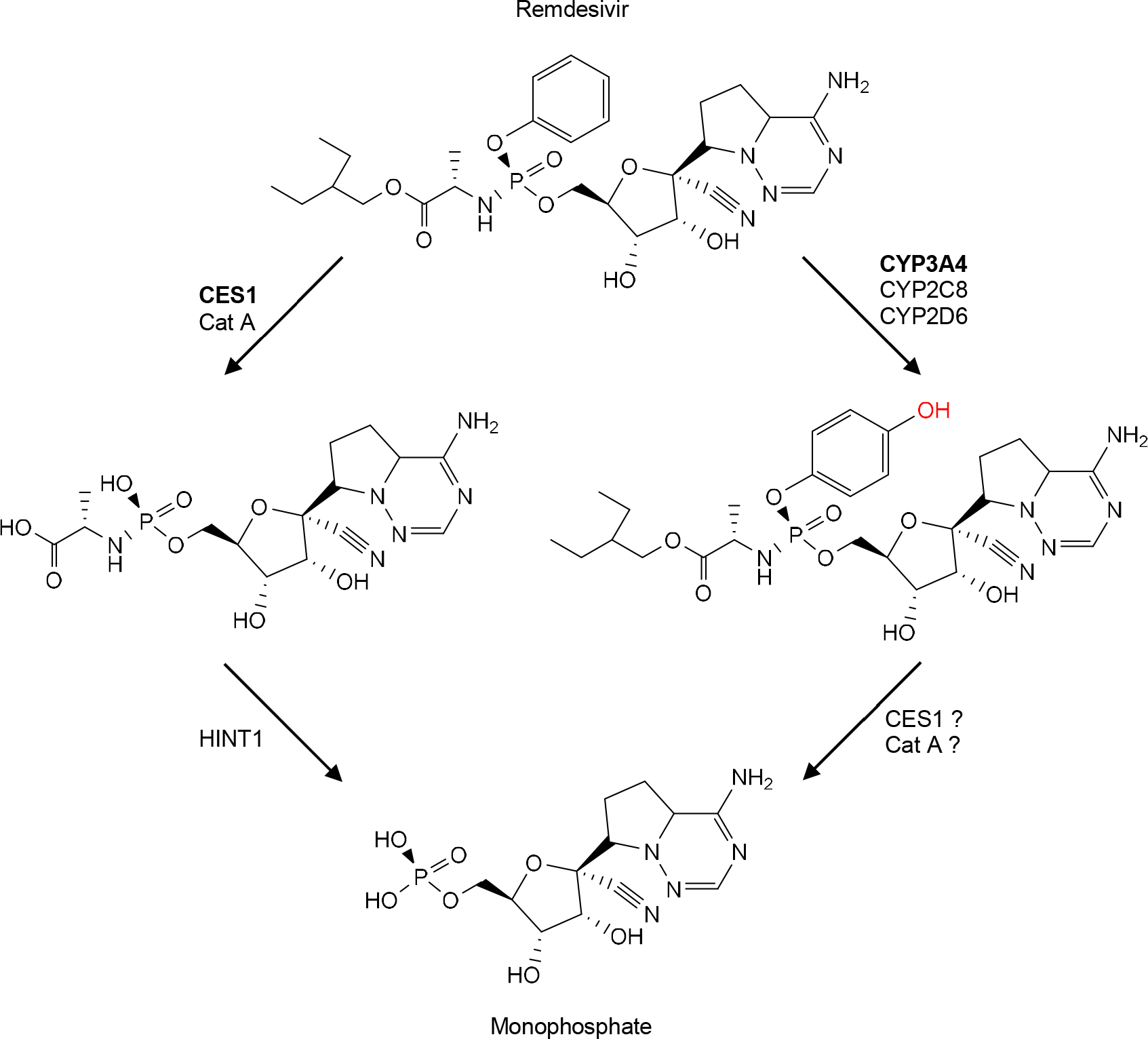

3–3. Metabolism of remdesivir

Remdesivir, like molnupiravir, is a carboxylic ester and structurally belongs to the superfamily of nucleoside analogs [99, 101]. Unlike molnupiravir, remdesivir has a core structure of hydroxyphenoxyphosphine (Top of Fig. 3) that is critical for therapeutic activation. Incubation with human liver microsomes, in the presence of NADPH, leads to a half-life of 1.1 min [92]. However, the absence of NADPH prolongs the half-life by almost 30 fold, to 30.6 min. It has been reported that remdesivir is a substrate of CYP2C8, 2D6 and 3A4. Cobicistat, a CYP3A4 inhibitor, completely inhibits oxidative metabolism of remdesivir, pointing to a major role of CYP3A4 in the oxidation. Nevertheless, both mono- and di-oxidation metabolites are detected, although the mono-oxidation metabolite reaches the peak much faster (5 min) [92]. Mass-spectrometric analysis of fragmentation pathways suggests that the initial oxidation occurs at the para position of the phenyl ring (Right of Fig. 3 in Red).

Fig 3. Metabolism of remdesivir.

This virial agent is a substrate of hydrolases (e.g., CES1) and CYP enzymes (e.g., CYP3A4). The hydrolytic metabolite is further hydrolyzed by HINT1 (Histidine triad nucleotide-binding protein 1, an amidase. It is likely that oxidized metabolite undergoes hydrolysis by CES1, Cat A or both.

It is well established that therapeutic activation of remdesivir is achieved by initial hydrolysis followed by phosphorylation [113]. The hydrolysis is catalyzed by CES1 and cathepsin A [91, 94, 114]. The relative contribution of these two enzymes to the hydrolysis varies depending on the tissue or cell type. While cathepsin A is kinetically more favorable toward remdesivir [91], CES1 is generally more abundant [94, 114]. It remains to be determined whether the oxidative metabolites of remdesivir are substrates of CES1 and/or cathepsin A (Fig.3). Nevertheless, the hydrolytic metabolite (alanine intermediate) generated by CES1 or cathepsin A undergoes further hydrolysis by histidine triad nucleotide-binding protein 1 to monophosphate (Fig. 3). The monophosphate metabolite undergoes two-step phosphorylation to form the final antiviral metabolite. As discussed with molnupiravir, the kinases for the phosphorylation remain to be determined. Likewise, NUDT18 has been shown to hydrolyze the therapeutically active metabolite as seen with NHC-TP triphosphate [111].

3–4. Drug transporters for molnupiravir, nirmatrelvir and remdesivir

Metabolism and active transport are highly coordinated events for drugs and their metabolites [115]. In contrast to metabolizing enzymes, the identities of transporters remain largely unknown for the membrane crossing of molnupiravir, nirmatrelvir and remdesivir or their metabolites. Nevertheless, it has been reported that equilibrative nucleoside transporters (ENTs) modestly support the uptake of molnupiravir but its hydrolytic metabolite NHC is a much better substrate of these transporters [116]. In VeroE6 P-glycoprotein knockout cells, nirmatrelvir has been shown to potently inhibit the replication of SARS-CoV-2 viruses, suggesting that nirmatrelvir is a substrate of P-glycoprotein [117], although the involvement of P-glycoprotein has not been fully confirmed [118]. In contrast to molnupiravir and nirmatrelvir, remdesivir has been identified to be a substrate of multiple transporters including BSEP, MATE1, MRP4, NTCP, OATP1B1/1B3 and OCT1 [119, 120]. These transporters are abundantly expressed in the liver. Interestingly, remdesivir is also a substrate of ENTs with a potency of 11–17 times of that of molnupiravir and 6 times of NHC, the hydrolytic metabolite of molnupiravir [116].

The higher efficiency of ENTs on the active transport of NHC, compared with that of its parent drug molnupiravir likely signifies a higher efficacy potency of NHC against SARS-CoV-2. As shown in Table 3, NHC is 1.6–5.6 times as potent as molnupiravir. Interestingly, GS-441524, the hydrolytic metabolite of remdesivir, is consistently less potent than its parent drug remdesivir. The differences in the relative lipophilicity between the parent drug and its metabolite likely accounts for such discrepancy. Remdesivir and its major metabolite GS-441524 have an XLogP3 value (an indicator for lipophilicity) of −1.4 and +1.9, respectively. These values constitute a relatively large net difference (i.e., 3.3), suggesting passive diffusion favoring remdesivir over GS-441524 for membrane-crossing. Remdesivir undergoes hydrolysis by CES1 and is eventually converted to GS-441524 [93]. The significantly higher efficacy of remdesivir than GS-441524 points to rapid diffusion and efficient hydrolysis in the SARS-CoV-2 infected cells. In contrast, molnupiravir and its hydrolytic metabolite NHC have an XLogP3 value of −0.8 and −2.2, resulting in a relatively small net difference (i.e., 1.4) [95]. Such difference points to an involvement of both passive and active transport to a similar extent for both molnupiravir and its hydrolytic metabolite NHC. As a result, NHC is moderately more potent than its parent drug molnupiravir.

4. POTENTIAL OF COMBINED USE OF SMALL MOLECULE COVID-19 MEDICINES

A combination medication has become an attractive strategy for various types of diseases, even for preventative purposes. This is particularly true with infectious diseases. The use of two or more antiretroviral medicines, commonly referred to as “cocktail therapy”, is currently the standard treatment for HIV infection and prophylactic purpose (human immunodeficiency virus) [121]. Combinations are usually made based on several important considerations: mechanism of action, host-metabolism and both. Mpro is the target of nirmatrelvir and conserved among coronaviruses [Lu et al., 2018]. RdRp, the target of molnupiravir and remdesivir, is highly conserved across all families of RNA virus [122]. As such, confirmation of properly combined use of these medicines for therapeutic synergy will likely have a broader clinical significance even beyond COVID-19 pandemic.

4–1. Metabolism-based rationale for combined use

As discussed above, molnupiravir, nirmatrelvir and remdesivir all undergo extensive metabolism. The metabolism may represent therapeutic activation or inactivation depending on a drug or the type of metabolism. For example, nirmatrelvir is metabolized primarily by oxidation and oxidized metabolites of nirmatrelvir no longer have therapeutic activities [71]. The oxidation of nirmatrelvir is primarily catalyzed by CYP3A4. Interestingly, this very P450 also oxidizes remdesivir, although the therapeutic potential of oxidized remdesivir remains to be determined [92]. Nevertheless, co-presence of remdesivir would competitively inhibit the oxidation of nirmatrelvir, thus enhancing the therapeutic activity of nirmatrelvir (Fig. 4). Nirmatrelvir is co-packaged along with the boosting agent ritonavir [123]. Ritonavir is a potent CYP3A4 inactivator and reduces the metabolism of nirmatrelvir [72]. Clearly remdesivir-nirmatrelvir co-package for COVID-19 has advantages over ritonavir-nirmatrelvir combination as both remdesivir and nirmatrelvir have anti-SARS-CoV-2 activity.

Fig 4. Potential interactions of remdesivir with nirmatrelvir or molnupiravir.

Remdesivir likely competitively inhibits nirmatrelvir, primarily through CYP3A4 (Top) or with molnupiravir through ENT transporters (Bottom). In addition, remdesivir covalently inhibits CES2, leading to decreased hydrolysis of molnupiravir. However, the covalent inhibition is reduced by CES1-hydrolysis of remdesivir.

Remdesivir, on the other hand, is hydrolytically activated, and the hydrolysis is catalyzed by CES1 [93]. At the same time, remdesivir is a covalent inhibitor of CES2 [94], a hydrolase that therapeutically activates molnupiravir [95, 103]. It has been shown that the expression of CES1 is inversely correlated with the inhibition of CES2, suggesting that remdesivir but not its hydrolytic metabolite is a CES2 inhibitor. Nevertheless, co-presence of remdesivir would likely impact the hydrolytic activation of molnupiravir. CES2 is abundantly expressed in the intestine and liver [124, 125]. Inhibition of CES2 by remdesivir likely increases the absorption and bioavailability of molnupiravir. In addition to hydrolytic metabolism, remdesivir and molnupiravir share uptake transporters (ENTs) for membrane crossing [116], representing another potential interaction for altered therapeutic activity of remdesivir and molnupiravir (Fig. 4). To take the advantage of remdesivir-molnupiravir interactions, the timing of drug administration is very important.

4–2. Viral target-based rationale for combined use

The mechanism of action is another critical factor to be considered for combined use of antiviral agents. It is generally accepted that combined use of drugs with distinct mechanisms of action has a reasonable chance of success in improving efficacy and safety. The anti-hepatitis C viral pill Harvoni, for example, contains a combination of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir and is more effective with a broader spectrum than sofosbuvir alone [126]. Ledipasvir is an inhibitor of NS5A, a hepatitis C virus protein [127], whereas sofosbuvir inhibits the RdRp of hepatitis C virus [128]. Likewise, many HIV medicines are fixed combinations of two or more drugs. Some of the combined drugs even share the metabolism of action. For example, Truvada contains emtricitabine and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, and both HIV drugs are nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor [129]. Truvada and Decovy are the only FDA approved medications for PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis) [129].

Mpro is the target of nirmatrelvir and RdRp is the target of molnupiravir and remdesivir (Table 2). The viral genomic RNA directs immediate translation of two large open reading frames, resulting in the production of polyproteins [130, 131] (Fig. 5). These polyproteins undergo processing to produce functional proteins including RdRp. Mpro plays a major role in protein processing [132]. RdRp, on the other hand, is responsible for the genome replication and production of subgenomic mRNAs. These subgenomic mRNAs are translated for production of accessary proteins, critical for viral assembling [131]. Clearly, co-inhibition of Mpro (nirmatrelvir) and RdRp (molnupiravir or remdesivir) represents a one-two pouch and likely produces synergistic activities against SARS-CoV-2 (Fig. 5). Even molnupiravir and remdesivir, although they share the target of RdRp, likely deliver additive or even synergistic activities as well. Molnupiravir targets RdRp and induces severe viral RNA mutations, commonly referred to as error catastrophe. Remdesivir, in contrast, targets RdRp and causes chain termination and arrests RNA synthesis of viral genome [61, 63, 133].

Fig 5. Mechanistic interplay among molnupiravir, nirmatrelvir and remdesivir.

Molnupiravir and remdesivir target RdRp, whereas nirmatrelvir covalently inhibits Mpro. likely competitively inhibits nirmatrelvir, primarily through CYP3A4 (Top) or with molnupiravir through ENT transporters (Bottom). In addition, remdesivir covalently inhibits CES2, leading to decreased hydrolysis of molnupiravir. However, the covalent inhibition is reduced by CES1-hydrolysis of remdesivir.

4–3. Experimental confirmation on additive/synergistic activities of combined use

The COVID-19 pandemic remains a major health concern worldwide, and SARS-CoV-2 is continuously evolving to new variants [134]. There is an urgent need to identify new antiviral drugs and develop therapeutic strategies. Combined use of recently authorized COVID-19 medicines has been actively pursued in animal and in vitro studies. Some exciting and promising results have been recently reported on the combined use of two or all three drugs: molnupiravir, nirmatrelvir and remdesivir. Li et al [135] has reported that molnupiravir and nirmatrelvir synergistically inhibit the infection of SARS-CoV-2 but the overall inhibitory patterns vary depending on a variant (e.g., Delta and Omicron) and a cell model (e.g., Calu-1 and organoids). Similar synergy is reported with BA.1 and 2 variants in Vero E6 cells by Gidari et al [136]. The synergy of the molnupiravir and nirmatrelvir combination is also confirmed in mice [137]. Interestingly, this mouse model shows less antiviral efficacy of the nirmatrelvir-remdesivir combination. It should be noted that all three drugs are used at 20 mg/kg twice daily for 5 days with the first two given orally whereas remdesivir intraperitoneally [137]. Clearly, the dosing regimen of remdesivir is much higher than those of molnupiravir and nirmatrelvir based on the recommended clinical regimens (Table 2). Nevertheless, several case reports have shown that a molnupiravir and remdesivir combination exerts a synergistic effect on reducing the severity of symptoms as well as the duration of hospitalization of COVID-19 patients [138]. Interestingly, favipiravir, another drug that targets RdRp, synergizes with molnupiravir in reducing infectious virus titers of SARS-CoV-2 in a hamster model [139].

5. CONCLUSION

The COVID-19 pandemic remains a major health concern worldwide, and SARS-CoV-2 is continuously evolving. There is an urgent need to identify new antiviral drugs and develop novel therapeutic strategies. Molnupiravir, nirmatrelvir and remdesivir are newly authorized COVID-19 medicines that have demonstrated high efficacy with reasonable safety profiles. They differ in the mechanism of action, presenting a strong foundation for combined use. Indeed, some in vitro and animal studies have shown promise of their combined use for enhanced activities. On the other hand, these drugs undergo extensive metabolism that determines their therapeutic potential. The metabolism pathways and the corresponding enzymes involved should be carefully considered during their combined use for therapeutic synergy.

FUNDING

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 AA030486, R01 AI172959, R21 HD109411 and R21AI153031 (Yan, B).

ABBREVIATIONS

- CES1

carboxyleslerase-1

- CES2

carboxylesterase-2

- COVID-19

coronavirus disease 2019

- CYP

cytochrome P450

- Mpro

main protease

- NHC

N-hydroxycytidine

- NHC-TP

NHC-triphosphate-triphosphate

- RdRp

RNA dependent RNA polymerase

- SARS-CoV

severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus

- SARS-CoV-2

severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS

None

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT

Not applicable

REFERENCES

- 1.Glatter KA, Finkelman P. History of the Plague: An Ancient Pandemic for the Age of COVID-19. Am J Med. 2021; 134(2):176–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jester B, Uyeki T, Jernigan D. Readiness for responding to a severe pandemic 100 years after 1918. Am J Epidemiol. 2018; 187(12):2596–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson NP, Mueller J. Updating the accounts: global mortality of the 1918–1920 “Spanish” influenza pandemic. Bull Hist Med. 2022; 76(1):105–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lindenbaum J, Greenough WB, Islam MR. Antibiotic therapy of cholera. Bull World Health Organ. 1967; 36(6):871–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pollitzer R Cholera studies: 1. History of the disease. Bull World Health Organ. 1954; 10(3):421–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siddique AK, Salam A, Islam MS, Akram K, Majumdar RN, Zaman K. et al. Why treatment centres failed to prevent cholera deaths among Rwandan refugees in Goma, Zaire. Lancet. 1995; 345(8946):359–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eisinger RW, Fauci AS. “Ending the HIV/AIDS Pandemic”. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2018; 24(3):413–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rogers L “Smallpox and Vaccination in British India During the Last Seventy Years”. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. 1945; 38 (3):135–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blower S, Bernoulli D. An attempt at a new analysis of the mortality caused by smallpox and of the advantages of inoculation to prevent it. Rev Med Virol. 2004;14(5):275–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krylova O, Earn DJD. Patterns of smallpox mortality in London, England, over three centuries. PLoS Biol. 2020; 18(2):e3000506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thèves C, Biagini P, Crubézy E. The rediscovery of smallpox. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014; 20(3):210–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Cock KM, Jaffe HW, Curran JW. Reflections on 40 Years of AIDS. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021; 27(6):1553–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.GBD 2017 HIV collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and mortality of HIV, 1980–2017, and forecasts to 2030, for 195 countries and territories: a systematic analysis for the global burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors study 2017. Lancet HIV 2017; 6(12):e831–e59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard at https://covid19.who.int/ Accessed February 12, 2023.

- 15.Marik PE, Kory P, Varon J, Iglesias J, Meduri GU. MATH+ protocol for the treatment of SARS-CoV-2 infection: the scientific rationale. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2020; 19(2):129–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soy M, Keser G, Atagündüz P, Tabak F, Atagündüz I, Kayhan S. Cytokine storm in COVID-19: pathogenesis and overview of anti-inflammatory agents used in treatment. Clin Rheumatol. 2020; 39(7):2085–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tian S, Hu W, Niu L, Liu H, Xu H, Xiao SY. Pulmonary Pathology of Early-Phase 2019 Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pneumonia in Two Patients With Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2020; 15(5):700–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Romagnoli S, Peris A, De Gaudio AR, Geppetti P. SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19: From the Bench to the Bedside. Physiol Rev. 2020; 100(4):1455–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mark A, Crumley JP, Rudolph KL, Doerschug K, Krupp A. Maintaining Mobility in a Patient Who Is Pregnant and Has COVID-19 Requiring Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation: A Case Report. Phys Ther. 2021; 101(1):pzaa189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luecke E, Jeron A, Kroeger A, Bruder D, Stegemann-Koniszewski S, Jechorek D. et al. Eosinophilic pulmonary vasculitis as a manifestation of the hyperinflammatory phase of COVID-19. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021; 147(1):112–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nasrollahi H, Talepoor AG, Saleh Z, Eshkevar Vakili M, Heydarinezhad P, Karami N. et al. Immune responses in mildly versus critically ill COVID-19 patients. Front Immunol. 2023; 14:1077236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Russo A, Davoli C, Borrazzo C, Olivadese V, Ceccarelli G, Fusco P. et al. Clinical Characteristics and Outcome of Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients Treated with Standard Dose of Dexamethasone or High Dose of Methylprednisolone. Biomedicines. 2022; 10(7):1548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wiersinga WJ, Rhodes A, Cheng AC, Peacock SJ, Prescott HC. Pathophysiology, Transmission, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A Review. JAMA. 2020; 324(8):782–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.COVID-19 Vaccination Clinical & Professional Resources https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19. Accessed February 12, 2023.

- 25.KATELLA K Comparing the COVID-19 Vaccines: How Are They Different? https://www.yalemedicine.org/news/covid-19-vaccine-comparison. Accessed February 12, 2023.

- 26.COVID-19 vaccines. https://vk.ovg.ox.ac.uk/vk/covid-19-vaccines. Accessed December 16, 2022 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hammarström L, Marcotte H, Piralla A, Baldanti F, Pan-Hammarström Q. Antibody therapy for COVID-19. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021, 21(6):553–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koley T, Madaan S, Chowdhury SR, Kumar M, Kaur P, Singh TP. et al. Structural analysis of COVID-19 spike protein in recognizing the ACE2 receptor of different mammalian species and its susceptibility to viral infection. 3 Biotech. 2021; 11(2):109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mutoh Y, Umemura T, Ota A, Okuda K, Moriya R, Tago M. et al. Effectiveness of monoclonal antibody therapy for COVID-19 patients using a risk scoring system. J Infect Chemother. 2022; 28(2):352–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aleem A, Olarewaju O, Pozun A. Evaluating And Referring Patients For Outpatient Monoclonal Antibody Therapy For Coronavirus (COVID-19) In The Emergency Department. 2022. Sep 6. In: StatPearls; [Internet]. Accessed December 20, 2022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dunne C, Lang E. WHO provides 2 conditional recommendations for casirivimab-imdevimab combination therapy in COVID-19. Ann Intern Med. 2022; 175(1):JC6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chigutsa E, O’Brien L, Ferguson-Sells L, Long A, Chien J. Population Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of the Neutralizing Antibodies Bamlanivimab and Etesevimab in Patients With Mild to Moderate COVID-19 Infection. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2021. Nov;110(5):1302–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dougan M, Nirula A, Azizad M, Mocherla B, Gottlieb RL, Chen P. et al. BLAZE-1 Investigators. Bamlanivimab plus Etesevimab in Mild or Moderate Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021; 385(15):1382–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jia Z, Gong W (2021) Will Mutations in the Spike Protein of SARS-CoV-2 Lead to the Failure of COVID-19 Vaccines? J Korean Med Sci. 2021; 36(18):e124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mansbach RA, Chakraborty S, Nguyen K, Montefiori DC, Korber B, Gnanakaran S. The SARS-CoV-2 Spike variant D614G favors an open conformational state. Sci Adv. 2021; 7(16):eabf3671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yan D, Ra OH, Yan B. The nucleoside antiviral prodrug remdesivir in treating COVID-19 and beyond with interspecies significance. Anim Dis. 2021; 1(1):15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Getz WM, Salter R, Luisa Vissat L, Koopman JS, Simon CP. A runtime alterable epidemic model with genetic drift, waning immunity and vaccinations. J R Soc Interface. 2021; 18(184):20210648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang HC, Lai YJ, Liao CC, Yang WF, Huang KB, Lee IJ. et al. Targeting conserved N-glycosylation blocks SARS-CoV-2 variant infection in vitro. EBioMedicine. 2021; 74:103712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lipsitch M, Krammer F, Regev-Yochay G, Lustig Y, Balicer RD. SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infections in vaccinated individuals: measurement, causes and impact. Nat Rev Immunol. 2022; 22(1):57–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martínez-Flores D, Zepeda-Cervantes J, Cruz-Reséndiz A, Aguirre-Sampieri S, Sampieri A, Vaca L. SARS-CoV-2 Vaccines Based on the Spike Glycoprotein and Implications of New Viral Variants. Front Immunol. 2021; 12:701501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wagner R, Hildt E, Grabski E, Sun Y, Meyer H, Lommel A. et al. Accelerated Development of COVID-19 Vaccines: Technology Platforms, Benefits, and Associated Risks. Vaccines (Basel). 2021; 9(7):747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ayele AG, Enyew EF, Kifle ZD. Roles of existing drug and drug targets for COVID-19 management. Metabol Open. 2021; 11:100103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou YW, Xie Y, Tang LS, Pu D, Zhu YJ, Liu JY. et al. Therapeutic targets and interventional strategies in COVID-19: mechanisms and clinical studies. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021; 6(1):317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alaaeldin R, Mustafa M, Abuo-Rahma GEA, Fathy M. In vitro inhibition and molecular docking of a new ciprofloxacin-chalcone against SARS-CoV-2 main protease. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2022; 36(1):160–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chaube U, Patel BD, Bhatt HG. A hypothesis on designing strategy of effective RdRp inhibitors for the treatment of SARS-CoV-2. 3 Biotech. 2023; 13(1):12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Singh R, Bhardwaj VK, Das P, Bhattacherjee D, Zyryanov GV, Purohit R. Benchmarking the ability of novel compounds to inhibit SARS-CoV-2 main protease using steered molecular dynamics simulations. Comput Biol Med. 2022; 146:105572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhao Y, Deng S, Bai Y, Guo J, Kai G, Huang X. et al. Promising natural products against SARS-CoV-2: Structure, function, and clinical trials. Phytother Res. 2022; 36(10):3833–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.COVID-19 Clinical Trials https://covid19.nih.gov/clinical-trials#find-a-covid19-clinical-trial-1. Accessed February 12, 2023

- 49.Nie Z, Sun T, Zhao F. Safety and Efficacy of Antiviral Drugs for the Treatment of COVID-19: A Systematic Review. Infect Drug Resist. 2022; 15:4457–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang L, Liu J, Cao R, Xu M, Wu Y, Shang W. et al. Comparative Antiviral Efficacy of Viral Protease Inhibitors against the Novel SARS-CoV-2 In Vitro. Virol Sin. 2020; 35(6):776–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Purwati Miatmoko A, Nasronudin Hendrianto E, Karsari D, Dinaryanti A. et al. An in vitro study of dual drug combinations of anti-viral agents, antibiotics, and/or hydroxychloroquine against the SARS-CoV-2 virus isolated from hospitalized patients in Surabaya, Indonesia. PLoS One. 2021; 16(6):e0252302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.FDA Approves First Treatment for COVID-19: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-treatment-covid-19. Accessed October 22, 2020.

- 53.Singh AK, Singh A, Singh R, Misra A. An updated practical guideline on use of molnupiravir and comparison with agents having emergency use authorization for treatment of COVID-19. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2022; 16(2):102396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Heilmann E, Costacurta F, Geley S, Mogadashi SA, Volland A, Rupp B. et al. A VSV-based assay quantifies coronavirus Mpro/3CLpro/Nsp5 main protease activity and chemical inhibition. Commun Biol. 2022; 5(1):391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Marzi M, Vakil MK, Bahmanyar M, Zarenezhad E. Paxlovid: Mechanism of Action, Synthesis, and In Silico Study. Biomed Res Int. 2022; 2022:7341493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Warren TK, Jordan R, Lo MK, Ray AS, Mackman RL, Soloveva V. et al. Therapeutic efficacy of the small molecule GS-5734 against Ebola virus in rhesus monkeys. Nature. 2016; 531(7594):381–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tian L, Pang Z, Li M, Lou F, An X, Zhu S. et al. Molnupiravir and Its Antiviral Activity Against COVID-19. Front Immunol. 2022; 13:855496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Raeburn A Product development process: The 6 stages (with examples). https://asana.com/resources/product-development-process. Accessed December 12, 2022.

- 59.Zhao Y, Fang C, Zhang Q, Zhang R, Zhao X, Duan Y. et al. Crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 main protease in complex with protease inhibitor PF-07321332. Protein Cell. 2022; 13(9):689–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Owen DR, Allerton CMN, Anderson AS, Aschenbrenner L, Avery M, Berritt S. et al. An oral SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitor clinical candidate for the treatment of COVID-19. Science. 2021; 374(6575):1586–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Malone B, Campbell EA. Molnupiravir: coding for catastrophe. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2021; 28(9):706–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang L, Zhang D, Wang X, Yuan C, Li Y, Jia X. et al. 1’-Ribose cyano substitution allows Remdesivir to effectively inhibit nucleotide addition and proofreading during SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA replication. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2021; 23(10):5852–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gordon CJ, Tchesnokov EP, Feng JY, Porter DP, Götte M. The antiviral compound remdesivir potently inhibits RNA-dependent RNA polymerase from Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J Biol Chem. 2020; 295(15):4773–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bojkova D, Widera M, Ciesek S, Wass MN, Michaelis M, Cinatl J Jr. Reduced interferon antagonism but similar drug sensitivity in Omicron variant compared to Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 isolates. Cell Res. 2022; 32(3):319–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Padhi AK, Tripathi T. Hotspot residues and resistance mutations in the nirmatrelvir-binding site of SARS-CoV-2 main protease: Design, identification, and correlation with globally circulating viral genomes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2022; 629:54–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Manjunath R, Gaonkar SL, Saleh EAM, Husain K. A comprehensive review on Covid-19 Omicron (B.1.1.529) variant. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2022; 29(9):103372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Showers WM, Leach SM, Kechris K, Strong M. Longitudinal analysis of SARS-CoV-2 spike and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase protein sequences reveals the emergence and geographic distribution of diverse mutations. Infect Genet Evol. 2022; 97:105153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Saravolatz LD, Depcinski S, Sharma M. Molnupiravir and Nirmatrelvir-Ritonavir: Oral COVID Antiviral Drugs. Clin Infect Dis. 2023; 1(1):165–71,. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Atmar RL, Finch N. New Perspectives on Antimicrobial Agents: Molnupiravir and Nirmatrelvir/Ritonavir for Treatment of COVID-19. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2022; 66(8):e0240421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed) [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US); https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK501922/#IX-R. Accessed February 12, 2023 [Google Scholar]

- 71.Eng H, Dantonio AL, Kadar EP, Obach RS, Di L, Lin J. et al. Disposition of Nirmatrelvir, an Orally Bioavailable Inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 3C-Like Protease, across Animals and Humans. Drug Metab Dispos. 2022; 50(5):576–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lamb YN. Nirmatrelvir Plus Ritonavir: First Approval. Drugs 2022; 82(5):585–591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jayk Bernal A, Gomes da Silva MM, Musungaie DB, Kovalchuk E, Gonzalez A, Delos Reyes V. et al. Molnupiravir for Oral Treatment of Covid-19 in Nonhospitalized Patients. N Engl J Med. 2022; 386(6):509–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hammond J, Leister-Tebbe H, Gardner A, Abreu P, Bao W, Wisemandle W. et al. Oral Nirmatrelvir for High-Risk, Nonhospitalized Adults with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2022; 386(15):1397–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Beigel JH, Tomashek KM, Dodd LE, Mehta AK, Zingman BS, Kalil AC. et al. Remdesivir for the Treatment of Covid-19 - Final Report. N Engl J Med. 2020; 383(19):1813–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Goldman JD, Lye DCB, Hui DS, Marks KM, Bruno R, Montejano R. et al. Remdesivir for 5 or 10 Days in Patients with Severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 383: 2020; 383(19):1827–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wang Y, Zhang D, Du G, Du R, Zhao J, Jin Y. et al. Remdesivir in adults with severe COVID-19: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2020; 395(10236):1569–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Grein J, Ohmagari N, Shin D, Diaz G, Asperges E, Castagna A. et al. Compassionate Use of Remdesivir for Patients with Severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020; 382(24):2327–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Spinner CD, Gottlieb RL, Criner GJ, Arribas López JR, Cattelan AM, Soriano Viladomiu A. et al. Effect of Remdesivir vs Standard Care on Clinical Status at 11 Days in Patients With Moderate COVID-19: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2020; 324(11):1048–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Meo SA, Meo AS, Al-Jassir FF, Klonoff DC. Omicron SARS-CoV-2 new variant: global prevalence and biological and clinical characteristics. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2021; 25(24):8012–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lino A, Cardoso MA, Martins-Lopes P, Gonçalves HMR. Omicron - The new SARS-CoV-2 challenge? Rev Med Virol. 2022; 32(4):e2358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shrestha LB, Foster C, Rawlinson W, Tedla N, Bull RA. Evolution of the SARS-CoV-2 omicron variants BA.1 to BA.5: Implications for immune escape and transmission. Rev Med Virol. 2022; 32(5):e2381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Blanquart F, Hozé N, Cowling BJ, Débarre F, Cauchemez S. Selection for infectivity profiles in slow and fast epidemics, and the rise of SARS-CoV-2 variants. Elife. 2022; 11:e75791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Islam S, Islam T, Islam MR. New Coronavirus Variants are Creating More Challenges to Global Healthcare System: A Brief Report on the Current Knowledge. Clin Pathol. 2022; 15:2632010X221075584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Uraki R, Kiso M, Iida S, Imai M, Takashita E, Kuroda M. et l. Characterization and antiviral susceptibility of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.2. Nature. 2022; 607(7917):119–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Vangeel L, Chiu W, De Jonghe S, Maes P, Slechten B, Raymenants J. et al. Remdesivir, Molnupiravir and Nirmatrelvir remain active against SARS-CoV-2 Omicron and other variants of concern. Antiviral Res. 2022; 198:105252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Toots M, Yoon JJ, Hart M, Natchus MG, Painter GR, Plemper RK. Quantitative efficacy paradigms of the influenza clinical drug candidate EIDD-2801 in the ferret model. Transl Res. 218:16–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lo MK, Jordan R, Arvey A, Sudhamsu J, Shrivastava-Ranjan P, Hotard AL. et al. GS-5734 and its parent nucleoside analog inhibit filo-, pneumo-, and paramyxoviruses. Sci Rep 2017; 7:43395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Deb S, Reeves AA, Hopefl R, Bejusca R. ADME and Pharmacokinetic Properties of Remdesivir: Its Drug Interaction Potential. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2021; 14(7):655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Humeniuk R, Mathias A, Kirby BJ, Lutz JD, Cao H, Osinusi A. et al. Pharmacokinetic, Pharmacodynamic, and Drug-Interaction Profile of Remdesivir, a SARS-CoV-2 Replication Inhibitor. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2021; 60(5):569–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Li R, Liclican A, Xu Y, Pitts J, Niu C, Zhang J. et al. Key Metabolic Enzymes Involved in Remdesivir Activation in Human Lung Cells. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2021; 65(9):e0060221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Xie J, Wang Z. Can remdesivir and its parent nucleoside GS-441524 be potential oral drugs? An in vitro and in vivo DMPK assessment. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2021; 11(6):1607–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Shen Y, Eades W, Yan B. The COVID-19 medicine remdesivir is activated by carboxylesterase-1 and excessive hydrolysis increases cytotoxicity. Hepatol. Commun 2021; 5(9):1622–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Shen Y, Eades W, Yan B. Remdesivir potently inhibits carboxylesterase-2 through covalent modifications: signifying strong drug-drug interactions. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2021; 35(2):432–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Shen Y, Eades W, Liu W, Yan B. The COVID-19 Oral Drug Molnupiravir Is a CES2 Substrate: Potential Drug-Drug Interactions and Impact of CES2 Genetic Polymorphism In Vitro. Drug Metab Dispos. 2022; 50(9):1151–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Singh RSP, Walker GS, Kadar EP, Cox LM, Eng H, Sharma R. et al. Metabolism and Excretion of Nirmatrelvir in Humans Using Quantitative Fluorine Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy: A Novel Approach for Accelerating Drug Development. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2022; 112(6):1201–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Almazroo OA, Miah MK, Venkataramanan R. Drug Metabolism in the Liver. Clin Liver Dis. 2017; 21(1):1–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Rodrigues AD, Rowland A. Profiling of Drug-Metabolizing Enzymes and Transporters in Human Tissue Biopsy Samples: A Review of the Literature. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2020; 372(3):308–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Mirza AZ. Advancement in the development of heterocyclic nucleosides for the treatment of cancer - A review. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids. 2019; 38(11):836–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Liu HY, Lin YH, Lin PJ, Tsai PC, Liu SF, Huang YC. et al. Anti-HCV antibody titer highly predicts HCV viremia in patients with hepatitis B virus dual-infection. PLoS One. 2021; 16(7):e0254028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ramesh D, Vijayakumar BG, Kannan T. Advances in Nucleoside and Nucleotide Analogues in Tackling Human Immunodeficiency Virus and Hepatitis Virus Infections. Chem Med Chem. 2021; 16(9):1403–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Imran M, Kumar Arora M, Asdaq SMB, Khan SA, Alaqel SI, Alshammari MK et al. Discovery, development, and patent trends on molnupiravir: A Prospective Oral Treatment for COVID-19. Molecules. 2021; 26(19):5795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Eades W, Liu W, Shen Y, Shi Z, Yan B. Covalent CES2 Inhibitors Protect against Reduced Formation of Intestinal Organoids by the Anticancer Drug Irinotecan. Curr Drug Metab. 2022; In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Holmes R, Wright M, Laulederkind S, Cox L, Hosokawa M, Imai T. et al. Recommended nomenclature for five mammalian carboxylesterase gene families: Human, mouse and rat Genes and proteins. Mammalian Genome. 2010; 21(9–10):427–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Shen Y, Shi Z, Yan B. Carboxylesterases: Pharmacological inhibition, regulated expression and transcriptional involvement of nuclear receptors and other transcription factors. Nucl Receptor Res. 2019; 6:101435. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Xiao D, Chen YT, Yang D, Yan B. Age-related inducibility of carboxylesterases by the antiepileptic agent phenobarbital and implications in drug metabolism and lipid accumulation. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012; 84(2):232–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Shi D, Yang J, Yang D, LeCluyse EL, Black C, You L. et al. Anti-influenza prodrug oseltamivir is activated by carboxylesterase human carboxylesterase 1, and the activation is inhibited by antiplatelet agent clopidogrel. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006; 319(3):1477–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Tang M, Mukundan M, Yang J, Charpentier N, LeCluyse EL, Black C. et al. Antiplatelet agents aspirin and clopidogrel are hydrolyzed by distinct carboxylesterases, and clopidogrel is transesterificated in the presence of ethyl alcohol. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006; 319(3):1467–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Liu W, Yu S, Yan B. Effect of alcohol exposure on the efficacy and safety of tenofovir alafenamide fumarate, a major medicine against human immunodeficiency virus. Biochem Pharmacol. 2022; 204:115224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Hamlin AN, Tillotson J, Bumpus NN. Genetic variation of kinases and activation of nucleotide analog reverse transcriptase inhibitor tenofovir. Pharmacogenomics. 2019; 20(2):105–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Jemth AS, Scaletti ER, Homan E, Stenmark P, Helleday T, Michel M. Nudix hydrolase 18 catalyzes the hydrolysis of active triphosphate metabolites of the antivirals remdesivir, ribavirin, and molnupiravir. J Biol Chem. 2022; 298(8):102169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Kulikova VA, Nikiforov AA (2020) Role of NUDIX Hydrolases in NAD and ADP-Ribose Metabolism in Mammals. Biochemistry (Mosc). 2020; 85(8):883–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Wang B, Svetlov V, Wolf YI, Koonin EV, Nudler E, Artsimovitch I. Allosteric Activation of SARS-CoV-2 RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase by Remdesivir Triphosphate and Other Phosphorylated Nucleotides. mBio. 2021; 12(3):e0142321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Zhang F, Li HX, Zhang TT, Xiong Y, Wang HN, Lu ZH. et al. Human carboxylesterase 1A plays a predominant role in the hydrolytic activation of remdesivir in humans. Chem Biol Interact. 2022; 351:109744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Sawant-Basak A, Obach RS. Emerging Models of Drug Metabolism, Transporters, and Toxicity. Drug Metab Dispos. 2018; 46(11):1556–1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Miller SR, McGrath ME, Zorn KM, Ekins S, Wright SH, Cherrington NJ. Remdesivir and EIDD-1931 interact with human equilibrative nucleoside transporters 1 and 2: Implications for reaching SARS-CoV-2 viral sanctuary sites. Mol Pharmacol. 2021; 100(6):548–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Rai DK, Yurgelonis I, McMonagle P, Rothan HA, Hao L, Gribenko A. et al. Nirmatrelvir, an orally active Mpro inhibitor, is a potent inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 Variants of Concern. bioRxiv, 2022; 01.17.466644 [Google Scholar]

- 118.de Vries M, Mohamed AS, Prescott RA, Valero-Jimenez AM, Desvignes L, O’Connor R et al. A comparative analysis of SARS-CoV-2 antivirals characterizes 3CLpro inhibitor PF-00835231 as a potential new treatment for COVID-19. J Virol. 2021; 95(10):e01819–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Ambrus C, Bakos É, Sarkadi B, Özvegy-Laczka C, Telbisz Á. Interactions of anti-COVID-19 drug candidates with hepatic transporters may cause liver toxicity and affect pharmacokinetics. Sci Rep. 2021; 11(1):17810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Dernoncourt A, Schmidt J, Duhaut P, Liabeuf S, Gras-Champel V, Masmoudi K. et al. COVID-19 in DMARD-treated patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases: Insights from an analysis of the World Health Organization pharmacovigilance database. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2022; 36(1):199–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Lu DY, Wu HY, Yarla NS, Xu B, Ding J, Lu TR. HAART in HIV/AIDS Treatments: Future Trends. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2018; 18(1):15–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Painter GR, Natchus MG, Cohen O, Holman W, Painter WP (2021) Developing a direct acting, orally available antiviral agent in a pandemic: the evolution of molnupiravir as a potential treatment for COVID-19. Curr Opin Virol. 2021; 50:17–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.COVID-19 Treatments and Medications https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/your-health/treatments-for-severe-illness.html. Accessed February 6, 2023.

- 124.Xie M, Yang D, Liu L, Xue B, Yan B (2002) Human and rodent carboxylesterases: immunorelatedness, overlapping substrate specificity, differential sensitivity to serine enzyme inhibitors, and tumor-related expression. Drug Metab Dispos. 2002; 30(5):541–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Chen YT, Trzoss L, Yang D, Yan B. Ontogenic expression of human carboxylesterase-2 and cytochrome P450 3A4 in liver and duodenum: postnatal surge and organ-dependent regulation. Toxicology. 2015; 330:55–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Maness DL, Riley E, Studebaker G. Hepatitis C: Diagnosis and Management. Am Fam Physician. 2021; 104:626–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Nakamoto S, Kanda T, Wu S, Shirasawa H, Yokosuka O (2014) Hepatitis C virus NS5A inhibitors and drug resistance mutations. World J Gastroenterol. 2014; 20(11):2902–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Feng JY, Ray AS. HCV RdRp, sofosbuvir and beyond. Enzymes. 2021;49:63–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Schinazi RF, Patel D, Ehteshami M. The best backbone for HIV prevention, treatment, and elimination: Emtricitabine+tenofovir. Antivir Ther. 2022; 27(2):13596535211067599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Gao H, Zhang Y, Jiang H, Hu X, Zhang Y, Zhou X. et al. Crystal structures of human coronavirus NL63 main protease at different pH values. Acta Crystallogr F Struct Biol Commun. 2021; 77(Pt 10):348–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.V’kovski P, Kratzel A, Steiner S, Stalder H, Thiel V. Coronavirus biology and replication: implications for SARS-CoV-2. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2021; 19(3):155–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Hu Q, Xiong Y, Zhu GH, Zhang YN, Zhang YW, Huang P. et al. The SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Mpro): Structure, function, and emerging therapies for COVID-19. Med Comm (2020) 2022; 3(3):e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Gordon CJ, Tchesnokov EP, Schinazi RF, Götte M. Molnupiravir promotes SARS-CoV-2 mutagenesis via the RNA template. J Biol Chem. 2021; 297(1):100770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Tracking SARS-CoV-2 variants https://www.who.int/activities/tracking-SARS-CoV-2-variants. Accessed January 16, 2023.

- 135.Li P, Wang Y, Lavrijsen M, Lamers MM, de Vries AC, Rottier RJ et al. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant is highly sensitive to molnupiravir, nirmatrelvir, and the combination. Cell Res. 2022; 32(3):322–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Gidari A, Sabbatini S, Schiaroli E, Bastianelli S, Pierucci S, Busti C. et al. The Combination of Molnupiravir with Nirmatrelvir or GC376 Has a Synergic Role in the Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 Replication In Vitro. Microorganisms. 2022; 10(7):1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Jeong JH, Chokkakula S, Min SC, Kim BK, Choi WS, Oh S. et al. Combination therapy with nirmatrelvir and molnupiravir improves the survival of SARS-CoV-2 infected mice. Antiviral Res. 2022; 208:105430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Hashemian SMR, Jamaati H, Khalili-Pishkhani F, Roshanzamiri S, Eskandari R, Shafigh N. et al. Molnupiravir in Combination with Remdesivir for Severe COVID-19 Patients Admitted to Hospital: a Case Series. Microbes, Infection and Chemotherapy, 2022; 2:e1366. [Google Scholar]

- 139.Abdelnabi R, Foo CS, Kaptein SJF, Zhang X, Do TND, Langendries L. et al. The combined treatment of Molnupiravir and Favipiravir results in a potentiation of antiviral efficacy in a SARS-CoV-2 hamster infection model. EBioMedicine. 2021; 72:103595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Greasley SE, Noell S, Plotnikova O, Ferre R, Liu W, Bolanos B. et al. Structural basis for the in vitro efficacy of nirmatrelvir against SARS-CoV-2 variants. J Biol Chem 2022; 298(6):101972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]