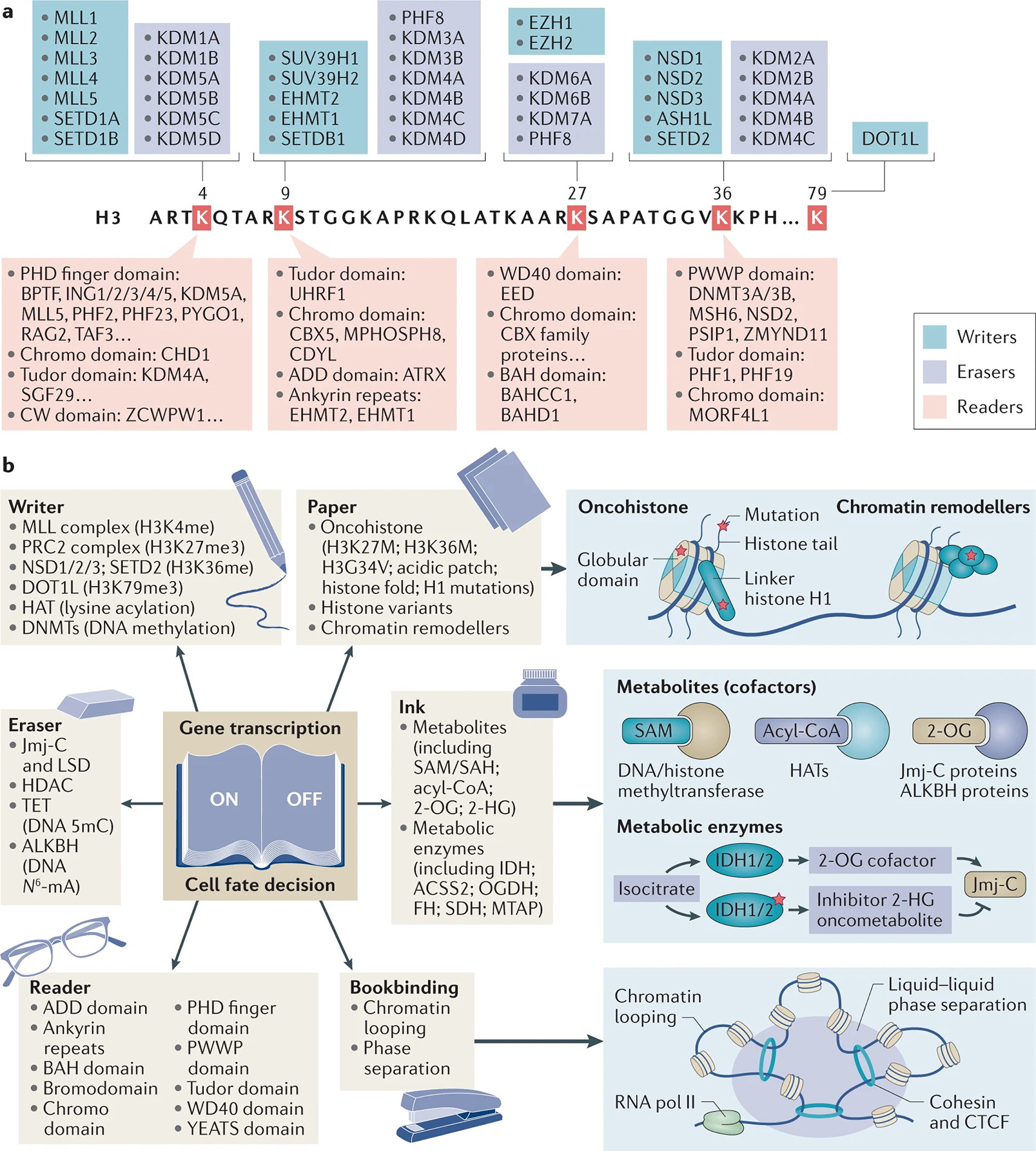

Figure 1. The misregulated ‘language’ of chromatin modification in cancer.

a. Overview of key writers, erasers and readers of histone H3 methylations at K4, K9, K27, K36 and K79. Note that this list is not exclusive; many other modifications such as acetylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitylation and arginine methylation also occur in all histones261, which are not shown in the figure.

b. A mis-regulated ‘language’ of chromatin modification underlies oncogenesis. In addition to cancer-related mutations of chromatin modification writers, erasers or readers, the oncohistone and chromatin remodeler mutations alter numerous fundamental aspects of chromatin, as illustrated by the ‘paper’ that the ‘language’ of chromatin modification operates on. Moreover, cellular metabolites and oncometabolites form essential cofactors for erasers, and also represent the ‘paint and ink’ used by writers (and in some cases erasers) to modify histones and DNA. A versatile set of readers allow cells to recognise and engage various chromatin marks such as lysine methylation, acetylation, crotonylation, and more. Similar to a process of ‘stapling and bookbinding’, chromatin looping and phase separation-based regulation are involved in the high-order organization of chromatin and regulation of (epi)-genome, processes frequently altered in cancers. Altogether, a collection of deregulated mechanisms converge, resulting in a mis-regulated chromatin ‘language’.