Abstract

BACKGROUND: Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic autoimmune disease affecting as many as 322,000 people in the United States. Because of heterogeneity in both disease course and clinical manifestations, it is critical to identify a prevalent SLE population that includes patients with moderate or severe disease. Additionally, differences in the clinical and economic burden of SLE may exist across payer channels, yet to date this has not been reported in any previous studies.

OBJECTIVE: To characterize the clinical and economic burden of SLE across disease severity and payer channels.

METHODS: This retrospective study included patients from Merative MarketScan Commercial, Medicare Supplemental, and Medicaid databases from 2013 to 2020 (Commercial/Medicare) or 2013 to 2019 (Medicaid), with at least 1 inpatient or at least 2 outpatient SLE claims and no invalid steroid claims. The index date was a random SLE claim with at least 12 months of disease history. Patients were continuously enrolled 1 year pre-index (baseline) and 1 year post-index and classified with mild, moderate, or severe disease using a published algorithm. Baseline demographics, clinical characteristics, flares, and utilization/costs were compared across disease severity.

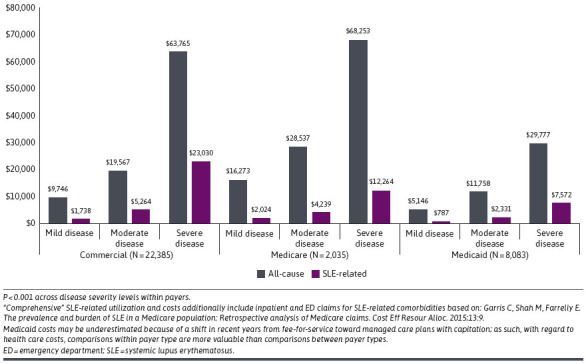

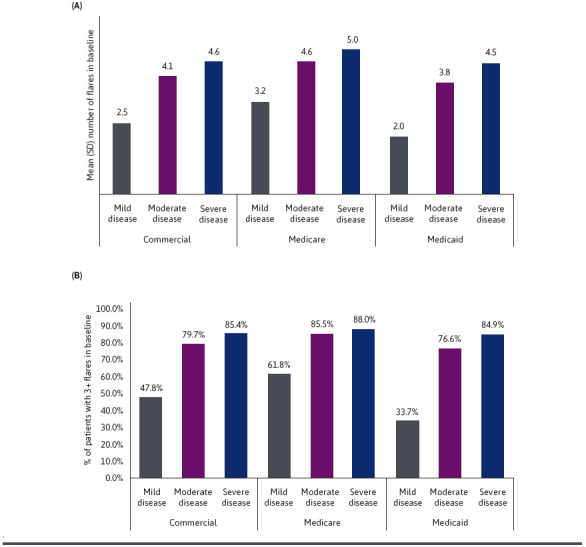

RESULTS: 22,385 Commercial, 2,035 Medicare, and 8,083 Medicaid patients had SLE. Most Medicaid patients (51.1%) had severe disease. Comorbidity scores increased with disease severity (P < 0.001). 30.7% of Commercial, 34.1% Medicare, and 51.3% Medicaid patients had opioids, which increased with disease severity (P < 0.001). All-cause costs ranged from 1.8- to 2.3-fold for moderate vs mild and 4.2- to 6.5-fold for severe vs mild. Outpatient medical costs accounted for the highest proportion of all-cause costs, except Medicaid patients with severe disease, for whom inpatient costs were highest. Mean (SD) SLE-related annual costs were $23,030 (43,304) vs $1,738 (4,427) in severe vs mild for Commercial, $12,264 (31,896) vs $2,024 (4,998) for Medicare, and $7,572 (27,719) vs $787 (3,797) for Medicaid (P < 0.001). For patients with severe disease in Medicaid, 16.5% and 60.1% had inpatient and emergency department (ED) visits, respectively, vs 10.3% and 26.5% Commercial vs 10.6% and 24.6% Medicare. Mean [SD] flares per year in the baseline period increased from 2.5 [1.7] in mild to 4.6 [1.9] in severe for Commercial, 3.2 [1.9] to 5.0 [2.1] for Medicare, and 2.0 [1.6] to 4.5 [2.0] for Medicaid.

CONCLUSIONS: Patients with severe SLE experienced more comorbidities, flares, and utilization/costs. Outpatient costs were the largest driver of all-cause costs for Commercial and Medicare (and Medicaid for mild to moderate SLE). Medicaid beneficiaries had the highest rate of severe SLE, highest use of ED and inpatient services, and highest oral corticosteroid and opioid use but the lowest utilization of disease-modifying treatments. Results demonstrate an unmet need in SLE treatment, especially among patients with moderate to severe disease or Medicaid coverage.

DISCLOSURES: This study was funded by AstraZeneca. Drs Wu and Bryant are current employees of AstraZeneca and may own stock and/or options. At the time of the study, Ms Perry and Mr Tkacz were employed by IBM Watson Health, which received funding from AstraZeneca to conduct this study.

Plain language summary

Patients with severe systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) had worse outcomes than patients without severe SLE. They had more comorbid conditions, more flares, and higher health care resources use and costs. Compared with patients with Commercial or Medicare coverage, those with Medicaid coverage had higher use of corticosteroids and opioids. These medications have adverse consequences associated with long-term use. Results from this study show an unmet need in SLE treatment, especially among patients with severe disease or with Medicaid coverage.

Implications for managed care pharmacy

This study quantifies the clinical and economic burden of SLE among prevalent patients stratified by both payer and disease severity, revealing that patients with severe disease and those with Medicaid coverage have the greatest need for improved disease management. The heterogeneity of the SLE patient population makes it challenging to identify those patient groups to prioritize for intervention. This study enables researchers, providers, and policy makers to pinpoint their efforts to the patients most in need.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a complex, chronic autoimmune disease affecting an estimated 241 per 100,000 people in the United States.1,2 It is characterized by inflammation affecting multiple organs and systems, including skin, joints, kidneys, lungs, central nervous system, and hematopoietic system, with cycles of lower disease status and more active disease (ie, flares).3 The variable clinical manifestations impact disease severity, which is based on organ involvement and the intensity of inflammation over time.4 Although there has been significant improvement in SLE prognosis, treating those with active disease and those with disease refractory to traditional therapies remains a challenge.5

Current SLE treatments include antimalarials, steroidal and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, and immunosuppressive drugs, where treatment escalation varies depending on disease severity.5 Although corticosteroids have clinical benefits, long-term use is associated with organ damage, toxicity, and increased resource use and costs.6 Further, opioids are prescribed to patients with SLE despite limited efficacy for managing chronic musculoskeletal pain and growing public health concerns around risks for addiction.7,8 Long-term opioid use may exacerbate comorbidities experienced by patients with SLE, including osteoporosis and cardiovascular disease.8 The variability of disease severity makes quantifying the burden of SLE a challenge. Nonetheless, being able to assess and measure the burden of SLE is necessary to address unmet medical needs, including managing the patient’s condition, maintaining a relatively low disease state, improving health outcomes, and lowering the economic burden of SLE.

Current literature on the burden of SLE has generally built on the newly diagnosed or newly treated SLE population. A few studies have observed significant health care resource utilization and medical costs, particularly among those with moderate or severe SLE.9,10 Additionally, more severe flares are associated with higher costs and more severe disease, as seen in a recent retrospective US study using linked claims and electronic medical records.11 This study reported that patients with SLE had an average of 3.5 flares annually and concluded that higher costs were largely driven by inpatient hospitalizations.11 Another linked retrospective study assessing the economic burden of patients with SLE by disease severity concluded that health care resource utilization and costs increase with disease severity in the year before and after diagnosis. This study found that leading cost drivers after diagnosis were outpatient visits followed by hospitalizations.10 Both of these prior studies focus on a newly diagnosed and largely a commercially insured population.10,11 Nonetheless, incident SLE populations with newly diagnosed/treated disease may not represent the burden of the general SLE population, in whom disease severity may have progressed.

To characterize the burden of SLE more accurately, it is critical to identify a prevalent SLE population that includes patients with moderate or severe disease progression without limiting to the newly diagnosed patients. In addition, differences in the clinical and economic burden of SLE may exist across payer channels such as those between the commercially vs publicly insured; however, to date, studies have not reported outcomes across different payers. This retrospective cohort study characterizes the clinical and economic burden of SLE using real-world data across SLE disease severity and payer channels in a prevalent population of patients with SLE with varying length of disease history to provide a more comprehensive view of SLE burden in the United States.

Methods

DATA SOURCE

This retrospective study used administrative claims data from the Merative MarketScan Commercial Database, Medicare Supplemental Database, and Multi-State Medicaid Database spanning January 1, 2013, through March 31, 2020 (Commercial and Medicare), and through December 31, 2019 (Medicaid). The MarketScan Commercial Database provides comprehensive and longitudinal views of health care encounters and costs, including for inpatient, outpatient, and outpatient prescription drug experiences for the working population and their dependents. The Medicare Supplemental Database contains medical and prescription data of retirees with Medicare Supplemental insurance paid for by an employer and includes data on both the Medicare-covered portions of payments and the employer-paid portions. The Medicaid Database contains the pooled health care experience of Medicaid enrollees from multiple geographically dispersed states, including all inpatient services, inpatient admissions, outpatient services, and prescription drug claims. All patient records are deidentified, and a unique identifier links each patient’s associated medical and pharmacy claims and enrollment information. Because this study used deidentified patient records, pursuant to the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996, it did not require institutional review board waiver or approval. Study data were captured using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) and ICD-10-CM codes, Current Procedural Technology 4th edition codes, and Health Common Procedure Coding System and National Drug Codes.

STUDY DESIGN

Patients with at least 1 inpatient claim or at least 2 nondiagnostic outpatient claims (ie, not diagnostic tests or screening) separated by 30-365 days with an SLE diagnosis (ICD-9-CM codes 710.0 or ICD-10-CM codes M32.xx) were initially selected for the study. Patients who qualified exclusively via outpatient claims were required to have an outpatient SLE diagnosis associated with a rheumatologist or nephrologist visit. This specialist requirement was not applied to Medicaid because patients with SLE with Medicaid insurance often receive treatment from a primary care physician because of lack of immediate access to specialist care, and removing this criterion more accurately reflects how these patients access care.

Once the initial patient pool was selected, the index date was randomly selected among service dates of claims with an SLE diagnosis that were at least 12 months after the first SLE diagnosis claim used in the previously described qualification criteria. Patients were required to be aged at least 18 years on the index date and continuously enrolled for 12 months prior to (baseline period) and 12 months following the index date. The observation period for the current analysis was the 12-month baseline period and the index date (Supplementary Figure 1, available in online article). Patients were excluded if they had any clinically invalid oral corticosteroid claims (prednisone-equivalent doses > 200 mg or missing/zero value for days supply or quantity). Commercial, Medicare Supplemental, and Medicaid coverage was determined based on the patient’s health plan on index date.

SLE disease severity was adapted from a published algorithm by Garris et al,15 which included cardiorespiratory, gastrointestinal, neuropsychiatric, ophthalmic, and renal disease classifications. Patients were classified as having severe disease based on a prescription for a high-dose oral corticosteroid (≥ 60 mg/day), cyclophosphamide, or biologic or presence of SLE-related complications. For severe disease, the SLE-related complications included (but were not limited to) cardiac tamponade, intestinal pseudo-obstruction, aseptic meningitis, optic neuritis, and end-stage renal disease. Classification of moderate disease was based on a prescription for a moderate-dose oral corticosteroid (≥ 7.5 and < 60 mg/day), immunosuppressive other than cyclophosphamide, or intravenous immune globulin, or presence of SLE-related complications, such as myocarditis, acute pancreatitis, seizure, uveitis, and nephritis. The algorithm by Garris et al also included constitutional (nonviral hepatitis), hematologic (hemolytic anemia), and musculoskeletal (ischemic necrosis of bone) disease classifications for identifying moderate disease severity.15 Patients not meeting the definitions for severe or moderate disease were characterized as having mild disease.

STUDY MEASURES

During the baseline period, the number and proportion of patients with at least 1 medication claim for any SLE treatment use was reported by the following treatment classes: antimalarials, biologic therapies, immunosuppressants, oral corticosteroids (OCs), and systemic, intravenous, or injectable corticosteroids; opioid use was also captured. Cumulative total OC dose and average daily OC dose among patients with more than 1 OC claim were also measured during baseline.

Comorbid conditions were identified by at least 1 qualified diagnosis in any position during the baseline period. These included the overall Elixhauser Comorbidity Index (ECI) score13 as well as components of ECI and SLE-related comorbidities as used in the SLE-specific risk adjusted index developed by Ward: anxiety, avascular necrosis, cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, deep vein thrombosis/venous thromboembolic disease, fatigue, fever, fibromyalgia, fractures, glaucoma, headache, kidney transplant, lupus nephritis, osteoarthritis, osteoporosis, pleurisy/pleural effusion, pulmonary embolism, Raynaud disease, seizure, and thrombocytopenia.14

Patient demographic information was captured on index date and included age (continuous) and age group, sex, geographic region (Commercial/Medicare only), and insurance plan type.

All-cause and SLE-related health care resource utilization and costs were evaluated during baseline. All-cause visits were defined as any inpatient or outpatient visit regardless of diagnosis or treatment, although SLE-related visits were based on claims with an SLE diagnosis in any position, outpatient pharmacy claims for SLE treatments, and SLE-related comorbidities (as defined by Ward14) identified in any position of inpatient and emergency department (ED) claims. Costs included amounts paid by both health plans and patients for services, including medical and pharmacy costs. Care is provided to Medicaid enrollees mostly through capitated managed care, and therefore, health care costs are not comparable between Commercial/Medicare patients. All costs were adjusted for inflation using the medical care component of the Consumer Price Index obtained from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics and standardized to 2019/2020 US dollars.

SLE flares were identified during baseline using a previously published real-world algorithm validated with administrative claims.15

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Baseline characteristics were summarized descriptively. Counts and proportions were used to describe categorical variables, and means and SDs were used to describe continuous variables. Bivariate analyses were conducted to determine the association of study measures and disease severity, and statistical tests of significance were conducted using chi-square tests for dichotomous or categorical variables and dependent t-tests for continuous variables. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to detect significant differences across disease severity cohorts. An a priori critical α level of less than 0.05 was set as the threshold for statistical significance.

Results

STUDY PARTICIPANTS

Based on patient selection criteria, the study identified 22,385 eligible patients with SLE from the Commercial database (23.3% mild disease, 43.6% moderate disease, and 33.1% severe disease), 2,035 in the Medicare Supplemental Database (20.0% mild, 38.5% moderate, and 41.4% severe), and 8,083 in the Medicaid Database (14.7% mild, 34.2% moderate, and 51.1% severe) (Table 1; Supplementary Figure 2).

TABLE 1.

Patient Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

| Commercial patients (n = 22,385) | Medicare patients (n = 2,035) | Medicaid patients (n = 8,083) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild disease | Moderate disease | Severe disease | Mild disease | Moderate disease | Severe disease | Mild disease | Moderate disease | Severe disease | ||||

| SLE disease severity, N (%) | 5,219 (23.3) | 9,756 (43.6) | 7,410 (33.1) | —a | 408 (20.0) | 784 (38.5) | 843 (41.4) | —a | 1,187 (14.7) | 2,765 (34.2) | 4,131 (51.1) | —a |

| Demographicsb | ||||||||||||

| Age, mean (SD), years | 46.8 (11.3) | 46.3 (11.6) | 46.5 (11.4) | —a | 71.4 (6.7) | 71.2 (7.2) | 71.4 (8.0) | — | 40.2 (12.2) | 40.1 (12.6) | 41.7 (12.0) | —a |

| Sex, % | ||||||||||||

| Female | 92.4 | 91.1 | 92.0 | —a | 90.0 | 87.2 | 88.3 | — | 93.4 | 93.0 | 93.3 | — |

| Male | 7.6 | 9.0 | 8.0 | 10.1 | 12.8 | 11.7 | 6.6 | 7.0 | 6.7 | |||

| Geographic region, % | ||||||||||||

| Northeast | 21.5 | 19.2 | 19.3 | —a | 31.6 | 26.4 | 30.4 | —a | N/A | N/A | ||

| North central | 15.2 | 15.8 | 15.2 | 23.0 | 22.5 | 22.2 | ||||||

| South | 49.0 | 52.8 | 51.4 | 32.8 | 42.6 | 36.5 | ||||||

| West | 14.0 | 12.0 | 13.8 | 12.5 | 8.6 | 10.8 | ||||||

| Unknown | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | ||||||

| Insurance plan type, % | ||||||||||||

| Comprehensive/indemnity | 2.5 | 2.2 | 2.8 | —a | 27.5 | 24.0 | 24.2 | — | 36.1 | 37.3 | 44.0 | —a |

| EPO/PPO | 57.2 | 57.1 | 58.4 | 52.2 | 55.9 | 53.7 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.2 | |||

| POS/POS with capitation | 8.2 | 8.1 | 8.0 | 5.4 | 8.4 | 7.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |||

| HMO | 11.0 | 10.8 | 10.1 | 12.5 | 10.3 | 12.8 | 63.4 | 62.4 | 55.8 | |||

| CDHP/HDHP | 19.4 | 19.6 | 18.1 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |||

| Other/Unknown | 1.8 | 2.1 | 2.7 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |||

| Clinical characteristicsc | ||||||||||||

| Elixhauser Comorbidity Index, mean (SD) | 0.5 (3.9) | 1.8 (5.8) | 2.0 (9.6) | —a | 1.8 (5.4) | 4.7 (8.1) | 6.8 (11.0) | —a | 0.6 (5.7) | 2.5 (7.4) | 1.6 (11.6) | —a |

| SLE comorbidities,d % | ||||||||||||

| Anxiety | 8.4 | 10.8 | 29.9 | —a | 7.8 | 10.6 | 23.8 | —a | 19.1 | 23.0 | 47.3 | —a |

| Cardiovascular diseasee | 20.7 | 35.7 | 52.3 | —a | 43.4 | 62.2 | 81.3 | —a | 25.8 | 44.3 | 63.0 | —a |

| Chronic kidney disease | 0.1 | 14.4 | 18.2 | —a | 0.2 | 25.8 | 28.2 | —a | 0.2 | 13.1 | 17.6 | —a |

| Depression | 3.0 | 3.8 | 32.8 | —a | 2.7 | 4.3 | 26.6 | —a | 7.8 | 11.7 | 57.9 | —a |

| Fatigue | 12.2 | 15.8 | 23.0 | —a | 12.5 | 14.0 | 20.2 | —a | 10.8 | 17.3 | 21.3 | —a |

| Fibromyalgia | 10.5 | 14.8 | 21.8 | —a | 9.6 | 15.3 | 16.4 | —a | 16.6 | 23.5 | 28.9 | —a |

| Headache | 11.2 | 17.3 | 25.9 | —a | 6.4 | 10.6 | 15.9 | —a | 21.4 | 27.8 | 37.5 | —a |

| Osteoarthritis | 15.6 | 20.2 | 24.2 | —a | 46.8 | 48.5 | 51.1 | — | 13.6 | 22.6 | 27.3 | —a |

| SLE treatments, % | ||||||||||||

| Antimalarials | 70.3 | 73.4 | 67.4 | —a | 61.3 | 62.6 | 57.1 | — | 42.1 | 62.8 | 53.8 | —a |

| Biologics | 0.0 | 0.0 | 28.7 | N/A | 0.0 | 0.0 | 8.7 | N/A | 0.0 | 0.0 | 9.6 | N/A |

| Immunosuppressants | 0.0 | 52.1 | 47.5 | —a | 0.0 | 40.3 | 32.9 | —a | 0.0 | 41.8 | 35.2 | —a |

| OCs | 9.7 | 68.4 | 64.1 | —a | 14.7 | 58.2 | 51.2 | —a | 9.2 | 75.4 | 64.0 | —a |

| Systemic/IV/IJ corticosteroids | 21.0 | 33.9 | 44.2 | —a | 28.2 | 41.8 | 44.0 | —a | 18.5 | 35.0 | 41.6 | —a |

| Number of treatment classes,f % | ||||||||||||

| 0 Treatment classes | 22.5 | 3.4 | 5.9 | —a | 24.0 | 5.4 | 10.8 | —a | 45.1 | 6.4 | 12.6 | —a |

| 1 Treatment class | 56.0 | 16.2 | 16.9 | —a | 50.3 | 23.6 | 27.1 | —a | 41.1 | 19.4 | 22.9 | —a |

| 2 Treatment classes | 19.5 | 38.7 | 25.8 | —a | 23.3 | 40.2 | 28.8 | —a | 12.7 | 35.8 | 27.6 | —a |

| 3+ Treatment classes | 2.0 | 41.7 | 51.3 | —a | 2.5 | 30.9 | 33.3 | —a | 1.1 | 38.3 | 36.9 | —a |

| Cumulative total OC dose,g mean (SD), mg | 831.7 (692.6) | 1,319.6 (1,720.4) | 2,121.8 (3,452.1) | —a | 914.2 (695.4) | 1,464.6 (2,109.3) | 1,622.0 (2,199.7) | —a | 664.2 (640.4) | 1,406.1 (1,824.9) | 1,665.3 (2,183.4) | —a |

| Average daily OC dose,g mean (SD), mg | 4.4 (1.4) | 16.7(11.8) | 21.5(26.3) | —a | 4.1(1.7) | 15.9(11.8) | 18.8(25.3) | —a | 4.0(1.8) | 18.8(12.8) | 22.1(18.7) | —a |

| Opioid use, % | 17.2 | 28.9 | 42.5 | —a | 22.3 | 33.3 | 40.6 | —a | 31.8 | 47.6 | 59.4 | —a |

a P < 0.05.

b Demographics were measured on the index date.

c Clinical characteristics were measured during the 12-month period prior to the index date.

d The SLE-related comorbidities were adapted from Ward MM. J Rheumatol . 2000;27(6):1408-13.

e Cardiovascular disease is inclusive of cerebrovascular disease and myocardial infarction, as well as other cardiovascular-related conditions.

f Treatment classes are defined as antimalarials, biologics, immunosuppressants, OCs, systemic/IV/IJ corticosteroids.

g Oral corticosteroid dosing was measured in prednisone-equivalent doses.

CDHP = consumer-driven health plan; EPO = exclusive provider organization; HDHP = high deductible health plan; HMO = health maintenance organization; IJ = injectable; IV = intravenous; N/A = not available; OC = oral corticosteroid; POS = point of service; PPO = preferred provider organization; SLE = systemic lupus erythematosus.

PATIENT DEMOGRAPHIC AND CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS

The majority of patients across all subgroups were female (87.2%-93.4%) (Table 1). Mean (SD) overall age was 46.5 (11.5), 71.3 (7.4), 40.9 (12.3) years for Commercial, Medicare, and Medicaid, respectively; age was significantly different across disease severity levels for Commercial and Medicaid (P < 0.05) (Table 1). Across all payer channels, mean ECI increased with SLE disease severity with patients with severe SLE having mean ECI scores 2.7-4.0–fold higher than those with mild disease (all P < 0.001) (Table 1). The most frequently observed baseline comorbidities included cardiovascular disease (20.7%-81.3%), osteoarthritis (13.6%-51.1%), anxiety (7.8%-47.3%), headache (6.4%-37.5%), fatigue (10.8%-23.0%), fibromyalgia (9.6%-28.9%), and chronic kidney disease (0.1%-28.2%), with consistently increasing prevalence of comorbidities with increasing levels of disease severity (all P < 0.05) (Table 1) except for osteoarthritis among Medicare beneficiaries, where the proportions were not significantly different across disease severity levels.

Antimalarials (42.1%-73.4%) were the most commonly prescribed therapy, with the highest use among the commercially insured patients. Biological therapies were used by 28.7% patients in Commercial, 8.7% in Medicare, and 9.6% in Medicaid-insured, among patients with severe SLE (Table 1). OCs were used more frequently by patients with moderate to severe SLE (51.2%-75.4%) than by patients with mild SLE (9.2%-14.7%) (Table 1). Across all payer channels, total cumulative and average daily OC doses increased as disease severity increased (all P < 0.05) (Table 1). Between 18.5% and 28.2% of patients with mild, 33.9% and 41.8% with moderate, and 41.6% and 44.2% with severe disease had a claim for a systemic/intravenous/injectable corticosteroid, which comprehensively included implants, injectables, and inserts, as well as powders for solutions, injections, and suspensions.

Despite not being a standard treatment regimen for SLE, prescription opioid use was common among the overall SLE population, with 30.7% of Commercial, 34.1% of Medicare, and 51.3% of Medicaid beneficiaries filling at least 1 opioid prescription. Across disease severity, 17.2%-31.8% of patients with mild disease, 28.9%-47.6% of patients with moderate disease, and 40.6%-59.4% of patients with severe disease had at least 1 opioid prescription in baseline (Table 1; Supplementary Figure 3). Opioid use increased significantly as disease severity increased among all payer channels (all P < 0.001) and was particularly high among Medicaid beneficiaries, with more than half of those with severe disease (59.4%) filling an opioid prescription in the baseline period (Table 1; Supplementary Figure 3).

HEALTH CARE RESOURCE UTILIZATION AND COSTS

During baseline, across all payer channels, the proportion of patients with an all-cause inpatient admission was 4.1-5.4 times greater among patients with severe vs mild disease (all P < 0.001), and among those with an all-cause ED visit was 1.5-2.6 times greater (all P < 0.001). Mean all-cause inpatient length of stay was also significantly associated with increased disease severity, increasing from 3.0 to 5.1 days in Commercial, 3.2 to 5.4 in Medicare, and 3.3 to 5.1 in Medicaid (all P < 0.001). Mean all-cause total costs were 2.0-fold and 6.5-fold higher among patients with moderate and severe disease, respectively, as compared with mild in Commercial beneficiaries, 1.8-fold and 4.2-fold higher for Medicare beneficiaries, and 2.3-fold and 5.8-fold higher for Medicaid beneficiaries (Figure 1). Overall, mean outpatient medical costs accounted for the highest proportion of total all-cause health care costs, except for among Medicaid patients with severe disease. Of total all-cause health care costs, 61.0% of mild, 54.7% of moderate, and 54.5% of severe SLE were attributable to outpatient medical for Commercial; 56.6%, 56.4%, and 56.1%, respectively, in Medicare; and 50.0%, 43.2%, and 35.0% in Medicaid (Table 2). Although all-cause inpatient costs accounted for 12.9%-25.7% of total costs in Commercial and 22.2%-29.7% in Medicare, inpatient costs contributed to the highest proportion (42.4%) of total costs among Medicaid patients with severe disease (16.5% in mild and 30.0% in moderate disease) (Table 2).

FIGURE 1.

Mean Total All-Cause and SLE-Related Health Care Costs by Disease Severity

TABLE 2.

Mean All-Cause and SLE-Related Costs by Health Care Setting Costs and Disease Severity

| Commercial patients (n = 22,385) | Medicare patients (n = 2,035) | Medicaid patients (n = 8,083) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild disease | Moderate disease | Severe disease | Mild disease | Moderate disease | Severe disease | Mild disease | Moderate disease | Severe disease | ||||

| All-cause health care costs | ||||||||||||

| Inpatient costs, mean (SD) | 1,259 (7,984) | 3,556 (18,012) | 16,416 (80,705) | —a | 3,609 (17,443) | 5,689 (25,514) | 20,302 (59,555) | —a | 851 (9,532) | 3,526 (24,637) | 12,634 (56,481) | —a |

| Outpatient costs, mean (SD) | 5,945 (12,330) | 10,707 (21,499) | 34,783 (74,013) | —a | 9,214 (17,559) | 16,090 (33,690) | 38,289 (92,466) | —a | 2,573 (5,666) | 5,082 (10,580) | 10,426 (18,010) | —a |

| Pharmacy costs,b mean (SD) | 2,543 (9,659) | 5,304 (19,282) | 12,565 (49,324) | —a | 3,451 (4,912) | 6,758 (14,728) | 9,662 (18,010) | —a | 1,722 (11,329) | 3,150 (14,430) | 6,717 (40,735) | —a |

| Total health care costs, mean (SD) | 9,746 (19,332) | 19,567 (37,431) | 63,765 (127,142) | —a | 16,273 (28,454) | 28,537 (50,050) | 68,253 (119,932) | —a | 5,146 (17,243) | 11,758 (33,777) | 29,777 (76,397) | —a |

| SLE-related health care costs | ||||||||||||

| Inpatient costs,c mean (SD) | 193 (3,223) | 842 (6,995) | 4,872 (27,191) | —a | 813 (4,716) | 1,363 (9,623) | 4,518 (21,362) | —a | 153 (2,820) | 553 (5,283) | 3,417 (22,103) | —a |

| Outpatient costs,b mean (SD) | 1,032 (2,684) | 2,960 (14,724) | 12,920 (30,277) | —a | 669 (1,457) | 1,593 (7,744) | 5,281 (20,099) | —a | 530 (2,413) | 1,133 (3,725) | 2,427 8,756) | —a |

| Pharmacy costs, mean (SD) | 495 (686) | 1,365 (4,367) | 4,941 (15,632) | —a | 524 (723) | 1,176 (2,171) | 2,085 (10,213) | —a | 89 (296) | 556 (6,005) | 1,427 (13,037) | —a |

| Total health care costs,b mean (SD) | 1,738 (4,427) | 5,264 (17,222) | 23,030 (43,304) | —a | 2,024 (4,998) | 4,239 (12,572) | 12,264 (31,896) | —a | $787 (3,797) | 2,331 (9,619) | 7,572 (27,719) | —a |

a P < 0.05.

b Pharmacy cost does not include those dispensed in an inpatient setting (inpatient pharmacy costs are bundled with inpatient costs).

c “Comprehensive” SLE-related utilization and costs additionally include inpatient and ED claims for SLE-related comorbidities based on: Garris C, Shah M, Farrelly E. The prevalence and burden of SLE in a Medicare population: Retrospective analysis of Medicare claims. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2015;13:9.

ED = emergency department; SLE = systemic lupus erythematosus.

Although SLE-related health care resource utilization among patients with severe disease for both Commercial and Medicare patients was approximately 10% in the inpatient setting and 25% in the ED setting, these settings of utilization were higher among Medicaid beneficiaries, with 16.5% having an SLE-related inpatient admission and 60.1% with an ED visit. Mean (SD) total SLE-related annual health care costs were 13 times greater among patients with severe vs mild disease in Commercial ($23,030 [43,304] vs $1,738 [4,427]), 6 times greater in Medicare ($12,264 [31,896] vs $2,024 [4,998]), and 10 times greater in Medicaid ($7,572 [27,719] vs $787 [3,797]) (all P < 0.001) (Figure 1). The mean (SD) patient out-of-pocket portion of total SLE-related health care costs were also significantly associated with increased disease severity, with a 3.7-fold increase in Commercial ($1,258 [8,297] vs $338 [476]), 1.9-fold increase in Medicare ($296 [536] vs $154 [244]), and 4.0-fold increase in Medicaid ($14 [62] vs $4 [12]) costs (all P < 0.001) in baseline.

SLE FLARE PATTERNS

Overall, patients with SLE had an average of 2 to 5 flares during the baseline, varying by disease severity. Mean (SD) number of overall SLE flares per year increased 1.6- to 2.3-fold as baseline disease severity increased from mild to severe, specifically from 2.5 (1.7) in mild to 4.6 (1.9) in severe in Commercial, 3.2 (1.9) to 5.0 (2.1) in Medicare, and 2.0 (1.6) to 4.5 (2.0) in Medicaid (Figure 2A). Overall, 74.2% of Commercial, 81.8% of Medicare, and 74.6% of Medicaid beneficiaries had 3 or more flares. Across payer groups, the proportion of patients with at least 3 flares in baseline was positively associated with an increase in disease severity, from 47.8% in mild to 85.4% in severe disease among Commercial patients, 61.8% to 88.0% in Medicare, and 33.7% to 84.9% in Medicaid (Figure 2B).

FIGURE 2.

(A) Number of Flares in Baseline Year by Disease Severity and (B) Proportion of Patients With 3+ Flares in Baseline Year by Disease Severity

Discussion

To the authors’ knowledge, this study is among the first to characterize a prevalent population of patients with mild, moderate, and severe SLE across geographically diverse payers in the United States. This compares with previous literature that has focused on an incident population of newly diagnosed patients, which is less representative of the general SLE disease burden. Specifically, these results demonstrate a higher proportion of severe SLE disease than previous publications. More than half (51.1%) of Medicaid beneficiaries had severe disease, notably higher than for Commercial (33.1%) or Medicare (41.4%). Older age, presence of comorbidities, and increased oral corticosteroid doses were associated with increased disease severity.

Consistent with prior studies, this study found that increased SLE severity is associated with higher health care costs.15,16 One large Medicaid study found that mean annual SLE medical costs and trends varied over time, likely because of increasing frequency and severity of flares or worsening disease progression.17 Another recent study, which was limited to a German population of patients with SLE, quantified and compared both incident and prevalent populations to establish associations between disease severity and costs.18 This current US-based analysis is consistent with the German study’s findings of disease severity being an important driver of health care resource use and costs.18

This study enhances knowledge of the association between economic burden and SLE disease severity. One recent study found that health care costs were 2.2-fold higher for patients with moderate SLE and 5.1-fold higher for patients with severe SLE than those with mild SLE among a newly diagnosed population.10 Similarly, the present study observed an increasing trend in all-cause health care costs toward increased disease severity. These estimates were across 3 distinct payer channels, which ranged from 1.8-fold to 2.3-fold for moderate vs mild disease and 4.2-fold to 6.5-fold for severe vs mild disease.

Furthermore, the current results demonstrated a significant increase in all-cause and SLE-related inpatient and ED utilization with increasing disease severity. Two recent studies focused on a newly diagnosed population of mostly commercially insured patients and quantified the high average costs associated with severe disease, particularly in the inpatient hospital setting.10,11 One such study reported that 51% of patients with severe SLE had inpatient utilization,10 as compared with the current study’s finding of less than 25% of prevalent patients having an inpatient hospitalization. This discrepancy suggests that patients newly diagnosed with SLE tend to be admitted to the hospital more than established patients and highlights the need for early diagnosis to sufficiently manage disease. The current results build on prior findings that quantify the economic burden of SLE and highlight that, among a prevalent population, outpatient medical costs are the largest driver of total all-cause health care costs across Commercial and Medicare beneficiaries, as well as for Medicaid patients with mild and moderate SLE. In addition, the current results found that inpatient costs were particularly high among patients with severe disease in the Medicaid population, attributing to 42.4% of their total all-cause health care costs.

The present analyses evaluated SLE-related utilization by incorporating a previously published algorithm14 to account for health care encounters due to SLE-related comorbidities such as myocarditis, arthritis, or pleural effusion, as patients with SLE may encounter these more intensive settings of care due to the manifestation of SLE disease, and thus, comorbidities are often coded in lieu of SLE diagnoses. SLE-related utilization was shown to be particularly high among Medicaid beneficiaries with severe disease (16.5% with an inpatient admission and 60.1% with an ED visit) as compared with those with severe disease in Commercial (10.3% inpatient, 26.5% ED) and Medicare (10.6% inpatient, 24.6% ED). Of note, the high utilization of ED visits among the Medicaid population may also be attributable to the lack of access to designated outpatient care, and hence, some patients may seek emergency care as an extension of outpatient care.

Moreover, this study also quantified SLE flare rates across disease severity. The proportion of patients with 3 or more flares (of any disease severity) ranged from 33.7% to 88.0% across payer channels, with an increasing proportion among patients with increased disease severity. Among the commercially insured population, the present results report a proportion of 48%, 80%, and 85% of patients with 3 or more flares among patients with mild, moderate, and severe SLE, respectively, which is somewhat higher than those previously reported among a newly diagnosed population (42%, 74%, and 80%, respectively).11 This is likely because of the disease progression among the prevalent population of patients, increasing their likelihood of experiencing more flares in a given year.

This study also evaluated commonly prescribed SLE-related treatments and found that, although approximately one-third (29%) of Commercial beneficiaries with severe SLE received a biologic, less than 10% of Medicare or Medicaid patients with severe disease were prescribed a biologic. Use of antimalarials and immunosuppressants was highest among the commercially insured patients. These data highlighted potential coverage discrepancies across payer channels.

Although not standard recommended SLE treatment, opioids were found to be common among patients with SLE. Opioid use was similar in the Commercial and Medicare cohorts, with 30.7% of Commercial and 34.1% of Medicare beneficiaries having opioid use across disease severity. This is similar to previous studies that found similar widespread opioid use among patients with SLE, with one study reporting that nearly one-third of patients with SLE in an established cohort used prescription opioids.8 However, in this study, the prescription rate of opioids was especially high among the Medicaid patients: more than half of Medicaid beneficiaries (51.3%) had opioid use. Additionally, this study filled a gap in knowledge that opioids were prescribed at a higher rate among patients with moderate to severe SLE, where 47.7%-59.6% of patients with moderate to severe SLE were prescribed with opioids in the Medicaid population. Although this analysis examined opioid with a threshold of a single prescription and cannot determine whether opioid use was specific to SLE or a comorbid condition unrelated to SLE, the increasing proportion of opioid use is positively associated with SLE severity. This finding is particularly important because patients with SLE may be at higher risk for adverse consequences of long-term opioid therapy.8 This finding highlights an important need for clinicians managing SLE to better understand the heightened risks associated with opioid use and to consider nonopioid pain management strategies, particularly among those with severe disease or those with Medicaid coverage.

LIMITATIONS

There were several study limitations. This study relied on diagnosis codes, procedure codes, and pharmacy prescriptions in claims, which are subject to data coding limitations and data entry error, to identify patient clinical profile and study outcomes. In particular, the severity of SLE disease was determined using a proxy based on a previously published algorithm that employed claims with certain diagnosis and procedure codes.15 In addition, treatment outcomes were based on the assumption that patients took medications as prescribed. Furthermore, the chosen databases are limited to only those individuals with Commercial health coverage, Medicare Supplemental, or Medicaid coverage, so the results of this analysis may not be generalizable to patients with SLE with other insurance or without health insurance coverage.

Owing to the limited access to specialists experienced by Medicaid patients, the patient selection requirement did not require Medicaid patients to have a confirmed diagnosis from a rheumatologist or nephrologist visit, which means a Medicaid patient in the study could have been diagnosed with SLE by the primary care physicians alone. This specialist-assigned diagnosis criteria were relaxed for Medicaid so that underserved and undertreated SLE population would be preserved in the study sample. Nonetheless, a higher rate of moderate and severe SLE disease and higher rates of OCs and opioid use were still observed among the Medicaid population.

Medicaid costs accurately reflect the payment at the point of service for services covered by the Medicaid system, often through capitated care management. Consequentially, claim level paid amounts will not reflect the per-enrollee amount disbursed to these same plans for providing health care services, which may explain why total health care costs were lower among the Medicaid population. Additionally, this study did not capture patients with dual eligibility for both Medicare and Medicaid, whose clinical and utilization experiences may differ from those with either coverage.

Conclusions

To the authors’ knowledge, this study is among the first to provide a perspective on the clinical and economic burden of SLE by disease severity among a prevalent population across payers in the United States, which enhances insights on the burden and severity of this disease to patients, payers, and providers. Patients with moderate to severe SLE disease experienced higher rates of comorbidities and SLE flares, increased resource utilization and costs, and heightened rates of opioid use. SLE-related health care costs among patients with severe SLE were 6 to 13 times higher than those with mild SLE. Medicaid beneficiaries presented the highest rate of severe SLE, the highest use of ED and inpatient services, and the highest oral corticosteroid and opioid use, but they also presented the lowest utilization of disease-modifying treatments, suggesting barriers to care among these patients. Overall, the results from this study demonstrate potential unmet needs, including better diagnostic approaches to earlier identify disease and SLE treatments to protect against disease severity, especially among patients with moderate to severe SLE disease and those with Medicaid insurance.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge the programming services provided by Helen Varker and Richard Bizier, the analytical and writing support provided by Elisabetta Malangone-Monaco and Nicole M Zimmerman, and editorial support provided by Liisa Palmer and Megan Richards of Merative (formerly IBM Watson Health at the time of study).

REFERENCES

- 1.Cojocaru M, Cojocaru IM, Silosi I, et al. . Manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. Maedica (Bucur). 2011;6(4):330-6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stojan G, Petri M. Epidemiology of systemic lupus erythematosus: An update. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2018;30(2):144-50. doi:10.1097/BOR.0000000000000480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.García-Carrasco M, Mendoza Pinto C, Solís Poblano JC, et al. . Systemic lupus erythematosus. In: Anaya JM, Shoenfeld Y, Rojas-Villarraga A, et al., eds. Autoimmunity: From bench to bedside. El Rosario University Press; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bello GA, Brown MA, Kelly JA, et al. . Development and validation of a simple lupus severity index using ACR criteria for classification of SLE. Lupus Sci Med. 2016;3(1):e000136. doi:10.1136/lupus-2015-000136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yildirim-Toruner C, Diamond B. Current and novel therapeutics in the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127(2):303-12; quiz 13-4. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2010.12.1087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shah M, Chaudhari S, McLaughlin TP, et al. . Cumulative burden of oral corticosteroid adverse effects and the economic implications of corticosteroid use in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Ther. 2013;35(4):486-97. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2013.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Birt JA, Wu J, Griffing K, et al. . Corticosteroid dosing and opioid use are high in patients with SLE and remain elevated after belimumab initiation: A retrospective claims database analysis. Lupus Sci Med. 2020;7(1) doi:10.1136/lupus-2020-000435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Somers EC, Lee J, Hassett AL, et al. . Prescription opioid use in patients with and without systemic lupus erythematosus – Michigan Lupus Epidemiology and Surveillance Program, 2014-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(38):819-24. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6838a2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murimi-Worstell IB, Lin DH, Kan H, et al. . Healthcare utilization and costs of systemic lupus erythematosus by disease severity in the United States. J Rheumatol. 2021;48(3):385-93. doi:10.3899/jrheum.191187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiang M, Near AM, Desta B, et al. . Disease and economic burden increase with systemic lupus erythematosus severity 1 year before and after diagnosis: A real-world cohort study, United States, 2004-2015. Lupus Sci Med. 2021;8(1) doi:10.1136/lupus-2021-000503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hammond ER, Desta B, Near AM, et al. . Frequency, severity and costs of flares increase with disease severity in newly diagnosed systemic lupus erythematosus: A real-world cohort study, United States, 2004-2015. Lupus Sci Med. 2021;8(1) doi:10.1136/lupus-2021-000504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garris C, Shah M, Farrelly E. The prevalence and burden of systemic lupus erythematosus in a medicare population: Retrospective analysis of medicare claims. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2015;13:9. doi:10.1186/s12962-015-0034-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, et al. . Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8-27. doi:10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ward MM. Development and testing of a systemic lupus-specific risk adjustment index for in-hospital mortality. J Rheumatol. 2000;27(6):1408-13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garris C, Jhingran P, Bass D, et al. . Healthcare utilization and cost of systemic lupus erythematosus in a US managed care health plan. J Med Econ. 2013;16(5):667-77. doi:10.3111/13696998.2013.778270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Furst DE, Clarke A, Fernandes AW, et al. . Resource utilization and direct medical costs in adult systemic lupus erythematosus patients from a commercially insured population. Lupus. 2013;22(3):268-78. doi:10.1177/0961203312474087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li T, Carls GS, Panopalis P, et al. . Long-term medical costs and resource utilization in systemic lupus erythematosus and lupus nephritis: A five-year analysis of a large medicaid population. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61(6):755-63. doi:10.1002/art.24545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schwarting A, Friedel H, Garal-Pantaler E, et al. . The burden of systemic lupus erythematosus in Germany: Incidence, prevalence, and healthcare resource utilization. Rheumatol Ther. 2021;8(1):375-93. doi:10.1007/s40744-021-00277-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]