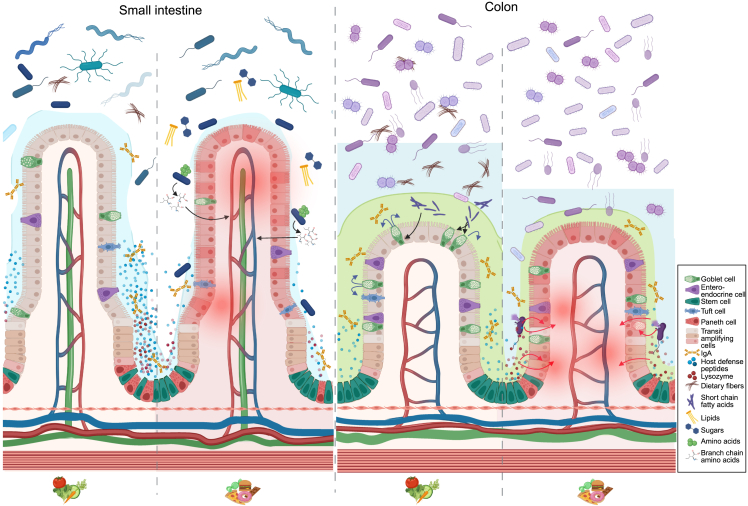

Figure 4.

Regional differences in host-diet-microbe interactions

In the healthy SI, conditioned by high-fiber dietary intake, crypt-residing Paneth cells secrete an ample amount of host defense peptides (HDPs). Barrier integrity is further bolstered by the loosely adherent mucus layer ensured by well-functioning goblet cells. Changing dietary habits from a balanced high-fiber diet to a typical westernized diet (low in fiber; high in fat, animal protein, and simple sugars) disrupts immune balance, mucus production, Paneth cell function, and microbiota composition. On a westernized diet, but not a balanced fiber-rich diet, Prevotella copri was able to enhance cross-epithelial transport of branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs), potentiating metabolic syndrome. Next, while dietary fibers are passing through the SI, they are metabolized by colonic microbes. The microbial metabolites from this process, SCFAs, stimulate goblet cell function, hence enhancing barrier integrity by increased mucus production. Conversely, in the inflamed colon—often mediated by disease activity potentiated by westernized diets—decreased mucus production enables bacterial encroachment to the otherwise sterile inner mucus layer. As a host-mediated counterresponse, this process fuels Paneth cell hyperplasia, enabling this cell type that is otherwise restricted to the SI to steadily emerge in the inflamed colon. Here, they secrete HDPs and lysozyme to ward of potential introducers. Since the microbial composition in colon diverges from the SI, so will the physiological response to, e.g., host-mediated defense mechanisms. As an example, Paneth cell-secreted lysozyme is one of the most important protectors of bacterial invasion in the SI. However, when these cells emerge in the inflamed colon, their secreted lysozyme promotes bacterial lysis of microbes. This includes the otherwise beneficial Ruminococcus gnavus, which is overly abundant in colon but not SI. Lysis of, e.g., R. gnavus liberates inflammatory effector molecules potentiating intestinal inflammation.41