Abstract

Recent reports based on a substantial number of cases, warrant need for population-based research to determine implications of constitutional methylation of tumor suppressor genes such as BRCA1 occurring in healthy tissue in the prediction of cancer. However, the detection of the constitutional methylation in DNA extracted from blood has already been shown to be technologically challenging, mainly because epimutations appear to be present in blood at a very low level. The analytical sensitivity required for low-level methylation detection can be provided by NGS, but this technique is still labor and cost-intensive. We assessed if PCR-based MS-HRM and BeadChip microarray technologies, which are standardized and cost-effective technologies for methylation changes screening, provide a sufficient level of analytical sensitivity for constitutional BRCA1 methylation detection in blood samples. The study included whole blood samples from 67 healthy women, 35 with previously confirmed and 32 with no detectable BRCA1 promoter methylation for which we performed both MS-HRM based BRCA1 gene methylation screening and genome wide methylation profiling with EPIC microarray. Our results shown, that low-level BRCA1 methylation can be effectively detected in DNA extracted from blood by PCR-based MS-HRM. At the same time, EPIC microarray does not provide conclusive results to unambiguously determine the presence of BRCA1 constitutional methylation in MS-HRM epimutation positive samples. The analytical sensitivity of MS-HRM is sufficient to detect low level BRCA1 constitutional epimutation in DNA extracted from blood and BeadChip technology-based microarrays appear not to provide that level of analytical sensitivity.

Subject terms: Epigenetics analysis, Breast cancer

Introduction

Breast cancer continues to be the most common neoplasm in females and recent reports suggest its rising incidence, especially in young women1. Germline mutations in BRCA1 are the most researched genetic lesion that increase the risk of breast cancer, but are present in only up to 5% of total breast cancer cases in Poland2. Constitutional methylation of BRCA1 detectable in blood cells was first associated with an increased risk of breast cancer tumors with features resembling BRCA1-mutated tumors over a decade ago3. Since that publication, several other studies investigated the prevalence of the methylation of BRCA1 promoter in peripheral blood and its association with cancer risk, but the results of those studies were frequently discrepant. The inconsistency of the results of previous studies can most likely be attributed to limited statistical power and different methylation detection methods used3–6. Especially, that the constitutional methylation of BRCA1 has been shown to be present at very low level in DNA extracted from whole blood. Thus, the sensitivity of the method for methylation detection appears to be critical in studies of constitutional BRCA1 gene methylation phenomenon. A recent study added a significant body of evidence for the utility of BRCA1 constitutional epimutation testing in blood in the prediction of both ovarian and breast cancers7. The study included 2478 of a triple-negative breast cancers (TNBCs) and 3493 high-grade serous ovarian cancers (HGSOCs) cases and controls without a germline pathogenic variant of BRCA1 and concluded that testing for BRCA1 epimutation in blood may have implications in cancer prediction. This study also used very sensitive technology for mutation changes detection (Next Generation Sequencing—NGS), and again detected methylation levels of BRCA1 in blood were low. NGS can provide required sensitivity for low level methylation detection but is still not cost-effective in the context of sequencing single PCR products. Additionally, the technique is laborious, especially because NGS data still require bioinformatics expertise to analyze. Thus, standardized, highly sensitive, and cost-effective methods for methylation detection are needed if BRCA1 methylation testing of large populations is considered.

The most frequently used methods for locus specific methylation changes testing are PCR-based methods and the most cost-effective method for genome-wide methylation studies are Methylation BeadChip microarrays (Illumina Inc). The PCR-based methods can provide state-of-the-art sensitivity but there is no consensus whether BeadChip microarrays provide sensitivity sufficient to assess constitutional methylation changes.

The largest study investigating association of the genome-wide methylation changes in pre-diagnostic blood samples with breast cancer risk (three independent cohorts of matched cases and controls: EPIC; n = 162, NOWAC; n = 168, BGS; n = 548) based on BeadChip microarray technology, did not find methylation changes at BRCA1 gene8, similarly to study by Severi G. et al.,9. At the same time a study based on blood derived from 30 breast cancer cases with BRCA1-like phenotype that also used BeadChip microarray, found elevated methylation levels in seven cancer cases with BRCA1-like phenotype, at the CpG sites within BRCA1 promoter that are most studied for constitutional methylation changes but reported methylation differences were less than 10%10. A more recent study found methylation differences at only one of the CpG sites in the BRCA1 promoter in the blood of breast cancer women and pre-diagnostic breast cancer cases and again here detected methylation level difference were less than 2%11.

With the new generation of the BeadChip microarrays dominating populational methylation studies, we performed a head-to-head comparison of analytical sensitivity of PCR-based Methylation Sensitive High-Resolution Melting (MS-HRM) and MethylationEPIC microarray for the BRCA1 constitutional methylation detection in DNA extracted from whole blood.

Methods

Our study included 67 blood samples from healthy women, 35 cases from our previous study tested positive for BRCA1 constitutional methylation12, and 32 controls with no detectable BRCA1 promoter methylation. The women underwent BRCA1/2 germline mutation screening at the International Hereditary Cancer Center in Szczecin in the years 2008–2015 with no germline mutations detected13. The mean age of the women positive for BRCA1 epimutation at sampling was 60.75 years (37–90) and for controls was 57.68 (50–69). The DNA was extracted using the salting-out method and bisulfite conversion of 300ng DNA was performed using EZ DNA Methylation Gold Kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA) following manufacturer protocol. The epimutation testing was performed using EpiMelt BRCA1 MS-HRM methylation screening kit (MethylDetect ApS, Denmark) and LightCycler® 480 High-Resolution Melting Master (Roche, Germany) using Q – qPCR Instrument (QuantaBio, UK). The kit used for methylation testing included apart from methylated and non-methylated controls, an assay calibration control that controls for 1% sensitivity of the methylation detection. The theoretical (not accounting for degradation of the template during bisulfite conversion and losses during sample preparation) concentration of the template in PCR was 5.45 ng/ul. The PCR was performed in triplicates in 50 cycles. Each cycle consisted of denaturation at 95 °C for 15s, primer annealing at 59 °C for 15s (as recommended by the manufacturer), and extension at 72 °C for 15s. The melting included an initial denaturing step at 95 °C for 15s and a stepwise increase in temperature from 67 to 90 °C with a rate of 0.025 °C/s. Then, the data were analyzed with Q-qPCR v1.0.2 software provided with the Q—qPCR Instrument. The Illumina MethylationEPIC v1.0 BeadChip (EPIC, Illumina Inc.) data were processed with the ChAMP package14 including data normalization with the BMIQ method. In total, 733,236 probes passed QC. No statistically significant differences between analyzed samples were detected with the EpiDISH R package modified as described in15 and none of the processed microarrays was a technical outlier according to MethylAid package16. The R version 4.1.3 was used for data processing and statistics calculation. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Pomeranian Medical University in Szczecin. Each patient has signed an informed consent for study participation.

Results

BRCA1 methylation levels in whole blood samples detected with MS-HRM are low

There is some discrepancy between studies regarding the part of the BRCA1 gene promoter that is targeted by assays aiming to detect constitutional methylation. The initial publication that demonstrated the association of the low-level promoter methylation of BRCA1 in blood with the development of BRCA1-like breast cancer (with tumor displaying features typical for cancer with mutated BRCA1 gene)3, targeted the region in which methylation changes had previously been associated with decreased BRCA1 mRNA levels in clinical breast cancer specimens17. The same region was targeted in subsequent studies that confirmed initial findings4 as well as our previous study of BRCA1 constitutional methylation in Polish population12. The MS-HRM assay we used in this study targets five CpG sites (chr17: 41277381–41277382, chr17: 41277389–41277390, chr17: 41277392–41277393, chr17: 41277394–41277395, chr17: 41277400–41277401) in that region.

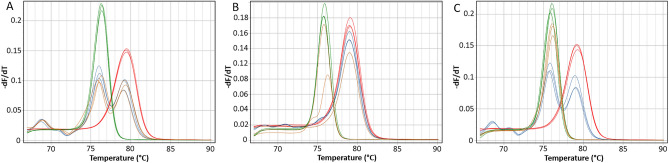

We reproducibly detected methylation in 29 samples in that region (Fig. 1A). In six of the screened samples, we did detect methylation, however not in all technical PCR replicates (Fig. 1B), and no methylation was detected in any of the control samples (Fig. 1C). The advantage of the MS-HRM protocol is that the sensitivity of the technology is annealing temperature dependent18. Therefore, in the attempt to reproducibly detect methylation in six samples in which the methylation was not detected in all PCR replicates, we re-tested those samples at raised the annealing temperature of 62 °C, and additionally doubled the amount of the template in the PCR. Nevertheless, this modification did not increase the reproducibility of the detection of methylation in those cases (data not shown) and the methylation detection was again not consistent between PCR replicates. Those results again indicates that analytical sensitivity of the method is critical for BRCA1 epimutation detection in blood as this epimutation may be present a very low level.

Figure 1.

Examples of the MS-HRM results for the BRCA1 constitutional methylation positive and negative samples: (A) sample positive for methylation run at 59 °C; (B) sample positive for methylation but not reproducibly detectable run at 61 °C; (C) sample negative for methylation run at 59℃. Color legend: red—100% methylated control, green—0% non-methylated control, blue—1% calibration control, orange—test sample.

Standard data processing of EPIC microarray data does not detect BRCA1 gene methylation changes

The EPIC microarray targets 59 CpG sites within the BRCA1 gene. We used the ChAMP pipeline (ChAMP.DMP) with default settings to identify differently methylated probes in the BRCA1 gene and data from 41 probes retained in the analysis after standard data quality control. The methylation levels at six of those probes were statistically significantly (FDR corrected p-value < 0.05) different between cases and controls in our study (Supplementary Data 1). However, the CpG sites targeted by those probes appear to be randomly distributed throughout BRCA1 1500TSS region. Moreover, none of those CpG sites mapped to, or was in the proximity to the region where constitutional methylation of BRCA1 was detected.

The analytical sensitivity of the assay is essential for the BRCA1 constitutional methylation detection in blood

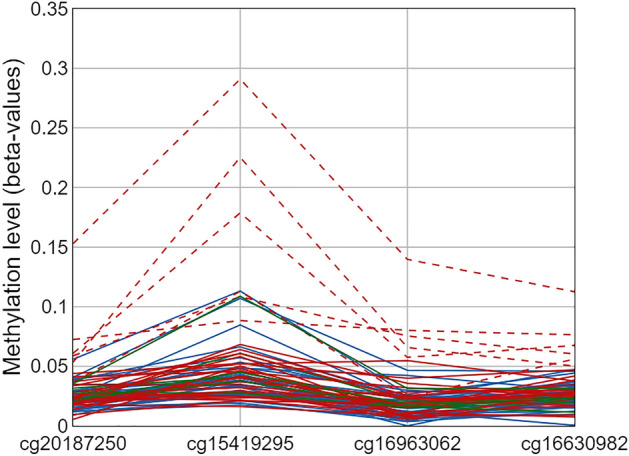

Four of the CpG sites targeted by the MS-HRM assay we used here, are also targeted by the EPIC BeadChip microarray. To assess the sensitivity of the MS-HRM and microarray we subdivided the MS-HRM results into three categories: positive methylation status (n = 29), methylation status detected stochastically (n = 6), and negative methylation status (n = 32) and compared methylation levels measured with MS-HRM for each of those groups with the methylation levels detected by EPIC microarray. Only six out of 29 samples positive for methylation in MS-HRM experiments (Fig. 2, samples indicated with red dashed lines) displayed methylation levels higher than the majority of the screened samples in microarray data. Apart from those samples, the methylation levels in samples positive for methylation (red solid lines Fig. 2), samples negative for methylation (blue solid lines Fig. 2), and samples positive for methylation but not reproducibly detectable (green solid lines Fig. 2) were very similar and around 5%, with only three samples exceeding that range for one of the screened probes.

Figure 2.

Methylation levels at four CpG sites within the region targeted by MS-HRM assay with samples positive for methylation indicated with red dashed and solid lines, samples negative for methylation indicated with blue lines, and samples positive for methylation but not reproducibly indicated with green lines.

We also tested mean methylation levels at the four probes targeted by MS-HRM for statistically significant differences between three groups of the samples divided according to MS-HRM results. The methylation level differences between compared groups were not statistically significantly different (Wilcoxon signed-rank test) and the largest observed mean methylation level difference was 2,4% at cg15419295, between samples positive for methylation and samples positive for methylation but not reproducibly detectable (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of mean methylation levels from EPIC microarray at four CpGs from the region targeted by MS-HRM assay between samples positive for methylation in MS-HRM analysis (denoted as Group 1), samples negative for methylation (denoted as Group 2) and samples positive for methylation but not reproducibly detectable (denoted as Group 3).

| CpG | Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Δ mean beta 1 versus 2 |

Δ mean beta 1 versus 3 |

Δ mean beta 2 versus 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cg20187250 | 0.034 | 0.026 | 0.024 | 0.007 | 0.010 | 0.002 |

| cg15419295 | 0.066 | 0.053 | 0.042 | 0.013 | 0.024 | 0.011 |

| cg16963062 | 0.031 | 0.020 | 0.016 | 0.012 | 0.015 | 0.003 |

| cg16630982 | 0.036 | 0.023 | 0.025 | 0.013 | 0.011 | -0.002 |

Discussion

A recent case–control study performed on thousands of cases and controls showed that constitutional methylation of BRCA1 gene promoter, detectable in blood cells is significantly associated with the risk of incident triple-negative breast cancers (TNBCs) and high-grade serous ovarian cancers (HGSOCs)7. The results of this study are generally in line with the results of previous studies, (including ours12), but those previous studies included significantly smaller number of patients3–6.

Overall, there seems to be sufficient research evidence to consider the potential implications of the BRCA1 constitutional methylation testing in normal tissue as well as other tumor suppressor genes for the prediction of cancer. However, the majority of studies reporting the association of the BRCA1 constitutional epimutation with cancer risk also show that if constitutional methylation is present in blood samples, it is present at a very low level4,19–21. Our results confirm that especially that in a few samples in our study, the concentration of the template originating from methylated BRCA1 promoter was so low that we were not able to reproducibly detect this epimutation in all PCR replicates.

The detection of low-level methylation is challenging from the technological point of view and requires highly sensitive methods. The use of the next generation sequencing, as in the most recent study overcomes the issue of method sensitivity. However, this technology is labor and cost-intensive. The PCR-based methods for methylation detection, as well as BeadChip technology-based microarrays, are significantly more cost and labor effective but detect methylation with varying sensitivity.

We compared the sensitivity of detection of methylation at the BRCA1 locus between PCR-based MS-HRM and EPIC microarray and showed that the sensitivity of the microarray is not sufficient to unambiguously detect low levels of methylation. This is an important observation because the largest population-based studies investigating genome-wide methylation changes in the context of breast cancer predisposition using BeadArray technology do not report BRCA1 methylation8,9 and our results clearly show that this may be attributed to the sensitivity of the method used in those studies.

In conclusion, an increasing number of studies report the association of methylation in healthy tissue with cancer incidence of not only BRCA1 but also other genes with known roles in carcinogenesis22. Those studies warrant further research to determine if constitutional methylation of tumor suppressor genes is a cancer risk factor. However, with the results we report here the choice of the methylation detection method appears to be critical in future studies of constitutional methylation in healthy tissues. Only methods with high and quantifiable sensitivity should be used in those studies. Those findings also apply in the context of screening for BRCA1 somatic epimutation in tumor tissue, when for example assessing the suitability of PARP inhibitors or platinum-based therapy for specific cancer patient groups.

Supplementary Information

Abbreviations

- BRCA1

BReast CAncer gene 1

- TNBC

Triple-negative breast cancers

- HGSOC

High-grade serous ovarian cancers

- PCR

Polimerase Chain Reaction

- MS-HRM

Methylation Sensitive High Resolution Melting

- HRM

High Resolution Melting

Author contributions

T.K.W., J.L., and T.H. recruited participants and conceived the concept and design of the study. F.M., K.E.S., K.B., S.R., D.S., M.S.K., prepared biological samples for wet‐lab analysis microarray MS-HRM as well as microarray experiments. F.M., K.E.S. performed bioinformatics data analysis under the supervision of T.K.W. T.K.W., K.E.S., and F.M. wrote, reviewed, and edited the first draft of the manuscript. All authors participated in data analysis, edited the manuscript as well as read and approved the final version.

Funding

The study was financed by the Polish National Agency for Academic Exchange, “The Polish Returns” program (PPN/PPO/2018/1/00088/U Grant Number), Polish budget funds under the “Diamentowy Grant” program (DI2019 017449 Grant Number), and PRELUDIUM BIS 2 grant from Polish National Science Centre (2020/39/O/NZ2/02943 Grant Number).

Data availability

The raw genome-wide profiling methylation data are available from the corresponding author upon justified request.

Competing interests

TKW is a shareholder of MethylDetect ApS. Other authors do not declare competing interests.

Footnotes

The original online version of this Article was revised: In the original version of this Article Filip Machaj was incorrectly listed as a corresponding author. The correct corresponding author for this Article is Tomasz Kazimierz Wojdacz. Correspondence and request for materials should be addressed to tomasz.wojdacz@pum.edu.pl.

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Filip Machaj and Katarzyna Ewa Sokolowska.

Change history

10/18/2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1038/s41598-023-44744-w

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-023-43276-7.

References

- 1.Ahmad A. Breast cancer statistics: Recent trends. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2019;1152:1–7. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-20301-6_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Górski B, et al. Breast cancer predisposing alleles in Poland. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2005;92:19–24. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-1409-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Snell C, Krypuy M, Wong EM, Loughrey MB, Dobrovic A. BRCA1 promoter methylation in peripheral blood DNA of mutation negative familial breast cancer patients with a BRCA1 tumour phenotype. BCR. 2008 doi: 10.1186/bcr1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wong EM, et al. Constitutional methylation of the BRCA1 promoter is specifically associated with BRCA1 mutation-associated pathology in early-onset breast cancer. Cancer Prev. Res. (Phila) 2011;4:23–33. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hansmann T, et al. Constitutive promoter methylation of BRCA1 and RAD51C in patients with familial ovarian cancer and early-onset sporadic breast cancer. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012;21:4669–4679. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iwamoto T, Yamamoto N, Taguchi T, Tamaki Y, Noguchi S. BRCA1 promoter methylation in peripheral blood cells is associated with increased risk of breast cancer with BRCA1 promoter methylation. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2011;129:69–77. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1188-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lønning PE, et al. Constitutional BRCA1 methylation and risk of incident triple-negative breast cancer and high-grade serous ovarian cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2022;8:1579–1587. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.3846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Veldhoven K, et al. Epigenome-wide association study reveals decreased average methylation levels years before breast cancer diagnosis. Clin. Epigenet. 2015 doi: 10.1186/s13148-015-0104-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Severi G, et al. Epigenome-wide methylation in DNA from peripheral blood as a marker of risk for breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-3209-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scott CM, et al. Genome-wide DNA methylation assessment of 'BRCA1-like' early-onset breast cancer: Data from the Australian Breast Cancer Family Registry. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2018;105:404–410. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2018.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tuminello S, et al. Global DNA methylation profiles in peripheral blood of wtc-exposed community members with breast cancer. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2022 doi: 10.3390/ijerph19095104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prajzendanc K, et al. BRCA1 promoter methylation in peripheral blood is associated with the risk of triple-negative breast cancer. Int. J. Cancer. 2020;146:1293–1298. doi: 10.1002/ijc.32655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janeway CA. Cellular cooperation during in vivo anti-hapten antibody responses. I. The effect of cell number on the response. J. Immunol. 1975;114:1394–1401. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.114.4.1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morris TJ, et al. ChAMP: 450k chip analysis methylation pipeline. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2014 doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bińkowski J, et al. Epigenetic activation of antiviral sensors and effectors of interferon response pathways during SARS-CoV-2 infection. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022;153:113396. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Iterson M, et al. MethylAid: visual and interactive quality control of large Illumina 450k datasets. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:3435–3437. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rice JC, Ozcelik H, Maxeiner P, Andrulis I, Futscher BW. Methylation of the BRCA1 promoter is associated with decreased BRCA1 mRNA levels in clinical breast cancer specimens. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:1761–1765. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.9.1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wojdacz TK, Borgbo T, Hansen LL. Primer design versus PCR bias in methylation independent PCR amplifications. Epigenetics. 2009 doi: 10.4161/epi.9020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gupta S, et al. Methylation of the BRCA1 promoter in peripheral blood DNA is associated with triple-negative and medullary breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2014;148:615–622. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-3179-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Snell C, et al. BRCA1 promoter methylation in peripheral blood DNA of mutation negative familial breast cancer patients with a BRCA1 tumour phenotype. Breast Cancer Res. 2008;10:R12. doi: 10.1186/bcr1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kontorovich T, Cohen Y, Nir U, Friedman E. Promoter methylation patterns of ATM, ATR, BRCA1, BRCA2 and p53 as putative cancer risk modifiers in Jewish BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation carriers. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2009;116:195–200. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0121-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Al-Moghrabi N, et al. Methylation of BRCA1 and MGMT genes in white blood cells are transmitted from mothers to daughters. Clin. Epigenetics. 2018;10:99. doi: 10.1186/s13148-018-0529-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw genome-wide profiling methylation data are available from the corresponding author upon justified request.