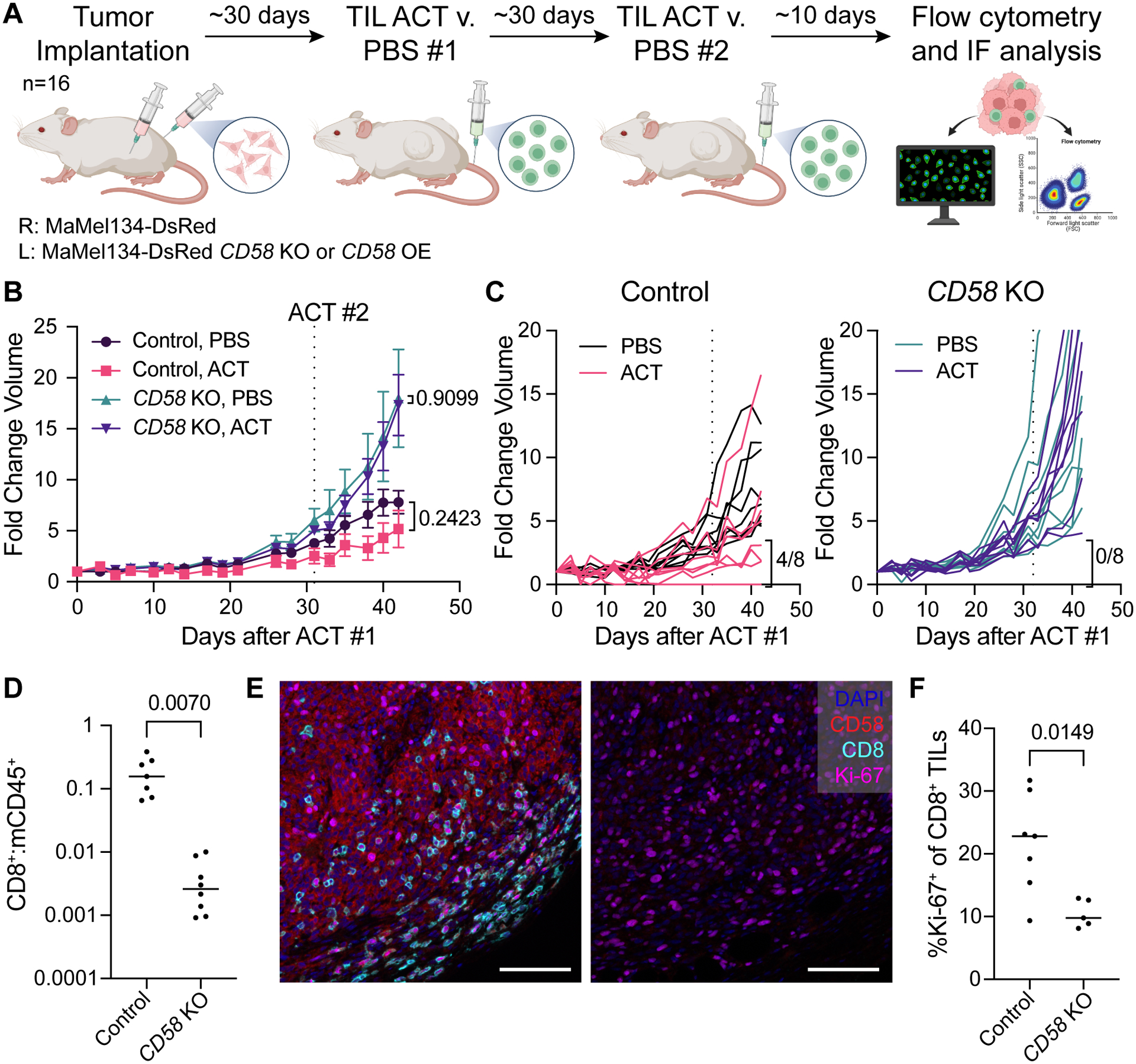

Figure 2. Loss of CD58 confers cancer immune evasion via impaired intratumoral T cell infiltration and proliferation.

(A) Experimental design of in vivo study of CD58 loss and re-expression in melanoma tumors. MaMel134 NLS-dsRed-expressing parental and CD58 KO or CD58-TM OE melanoma cells were implanted in NOG mice as bilateral subcutaneous flank injections, followed by two treatments with ACT of autologous TILs or PBS control (n=8 per treatment group).

(B-C) Fold change volume of control and CD58 KO tumors following initial ACT treatment or PBS control, with individual tumors shown in (C). For each group, individual tumors with partial or complete response to therapy, defined as <4-fold change in volume from initial ACT treatment to endpoint, are indicated.

(D) Ratio of human CD8+ cells to mouse CD45+ immune cells within ACT-treated control and CD58 KO tumors.

(E) Representative multiplexed immunofluorescence of FFPE tissue sections from mouse tumors staining for DAPI, CD58, CD8, and Ki-67. Scale bar = 100 μm.

(F) Percent of CD8+ TILs within ACT-treated control and CD58 KO tumors that express Ki-67. Statistical analysis performed using unpaired (B – PBS v. ACT) and paired (B – Control v. KO - D, F) two-sided T-tests. Line at median. Data represent mean ± SEM (B).