Abstract

Background:

Contemporary data on the prevalence of e-cigarette use in the United States are limited.

Objective:

To report the prevalence and distribution of current e-cigarette use among U.S. adults in 2016.

Design:

Cross-sectional.

Setting:

Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2016.

Participants:

Adults aged 18 years and older.

Measurements:

Prevalence of current e-cigarette use by sociodemographic groups, comorbid medical conditions, and states of residence.

Results:

Of participants with information on e-cigarette use (n = 466 842), 15 240 were current e-cigarette users, representing a prevalence of 4.5%, which corresponds to 10.8 million adult e-cigarette users in the United States. Of the e-cigarette users, 15% were never–cigarette smokers. The prevalence of current e-cigarette use was highest among persons aged 18 to 24 years (9.2% [95% CI, 8.6% to 9.8%]), translating to approximately 2.8 million users in this age range. More than half the current e-cigarette users (51.2%) were younger than 35 years. In addition, the age-standardized prevalence of e-cigarette use was high among men; lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) persons; current combustible cigarette smokers; and those with chronic health conditions. The prevalence of e-cigarette use varied widely among states, with estimates ranging from 3.1% (CI, 2.3% to 4.1%) in South Dakota to 7.0% (CI, 6.0% to 8.2%) in Oklahoma.

Limitation:

Data were self-reported, and no biochemical confirmation of tobacco use was available.

Conclusion:

E-cigarette use is common, especially in younger adults, LGBT persons, current cigarette smokers, and persons with comorbid conditions. The prevalence of use differs across states. These contemporary estimates may inform researchers, health care policymakers, and tobacco regulators about demographic and geographic distributions of e-cigarette use.

Primary Funding Source:

American Heart Association Tobacco Regulation and Addiction Center, which is funded by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

E-cigarettes were introduced in the United States more than a decade ago, with the general population perceiving these products as a safer substitute for combustible cigarettes (1). Subsequently, the prevalence of e-cigarette use has risen, especially among adolescents and younger adults (2). The medical community, however, remains concerned regarding both the safety of e-cigarettes and their utility as smoking cessation devices. In 2015, the American College of Physicians recommended that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) provide regulatory oversight of e-cigarettes, citing the lack of conclusive data on their safety and effectiveness as a cessation aid and their potential as a gateway to use of other tobacco products with known harms (3). In 2016, the FDA finalized the “Deeming Rule” that extended its regulatory authority beyond cigarettes and smokeless and roll-your-own tobacco to all tobacco products, including e-cigarettes, cigars, hookahs, and pipes (4). Therefore, the deeming rule gives the FDA authority to regulate e-cigarettes and to place health warnings and age restrictions on their sales.

Given the potential health concerns surrounding e-cigarettes, a detailed analysis of their contemporary use patterns takes on great importance. Although previous research from nationally representative data sets suggested rising e-cigarette prevalence, especially among younger adults, these studies are now outdated, and they were not sufficiently powered to report the prevalence of e-cigarette use among important subgroups (5, 6). Using the largest and most extensive dynamic health survey—the 2016 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) national survey—we aimed to determine the most up-to-date national and state-level prevalence of current e-cigarette use among U.S. adults. We also examined the prevalence of e-cigarette use among key demographic subgroups, which included stratification by cigarette smoking status.

These data may help delineate the complex relationship between e-cigarette use patterns and demographic, socioeconomic, and geographic factors and help inform the work of researchers, public health officials, and regulatory authorities seeking to understand current trends in e-cigarette use.

Methods

Data Source

The BRFSS is an extensive, nationally representative, health-related telephone panel survey conducted jointly by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and all states and participating territories of the United States. In summary, data were collected by landline and cellular telephone from 486 303 noninstitutionalized adults aged 18 years and older regarding risk behaviors, use of preventive services, and chronic health conditions (7).

Study Population and E-Cigarette Use

The BRFSS began collecting data on e-cigarette use in 2016. We included 466 842 persons (96% of the entire survey population) who provided information about e-cigarette use. First, the participants were asked, “Have you ever used an e-cigarette or other electronic ‘vaping’ product, even just one time, in your entire life?” Those who answered yes were asked a second question: “Do you now use e-cigarettes or other electronic ‘vaping’ products every day, some days, or not at all?” We considered participants who answered yes to the first question as ever– e-cigarette users. Of ever– e-cigarette users, we defined daily and occasional e-cigarette use as responding “every day” and “some days,” respectively. We defined current e-cigarette use as either daily or occasional.

In the assessment of prevalence estimates by subgroups, respondents with missing information on the subgroup of interest were excluded. Appendix Table 1 (available at Annals.org) provides information on the size of the study population for each subgroup examined. The sexual orientation and gender identity questions were asked in the following 26 states and territories: California, Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, Guam, Hawaii, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Nevada, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Texas, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, and Wisconsin. Response rates in the states that included these modules were 87.4% (sexual orientation) and 86.3% (gender identity).

Combustible Cigarette Smoking

Participants who answered yes to “Have you smoked at least 100 cigarettes in your entire life?” were considered ever– cigarette smokers, whereas those who answered no were considered never–cigarette smokers. Of ever– cigarette smokers, a second question was asked: “Do you now smoke cigarettes every day, some days, or not at all?” Participants who answered “every day” or “some days” were defined as current cigarette smokers, and those who answered “not at all” were defined as former cigarette smokers.

Other Study Measures

Key socioeconomic covariates of our analyses included age, sex (male or female), sexual orientation (heterosexual, lesbian, gay, or bisexual), gender identity (cisgender or transgender), race/ethnicity, educational attainment, relationship status (with partner or without partner), pregnancy, and employment. Household income was reported according to the federal poverty line in 2016 (8). Body mass index was calculated on the basis of self-reported height and weight. Information about lifestyle factors included physical activity (at least 1 exercise session during the past 30 days) and alcohol intake (at least 1 alcoholic drink during the past 30 days). Chronic health conditions included cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer (excluding skin cancer), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, depression, and chronic kidney disease. Participants with cardiovascular disease were defined as those who reported having myocardial infarction, coronary heart disease, or stroke. All variables were self-reported. For categorization of responses, we used BRFSS-defined criteria (9).

Weighting Process

In 2016, 50 states, the District of Columbia, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands collected data via landline and cellular telephone. The BRFSS uses a weighting methodology called raking that allows incorporation of landline and cellular telephone survey data and permits the introduction of additional characteristics that improve the degree to which the BRFSS sample accurately reflects the sociodemographic make-up of the United States as well as the individual states. More details on study design, sampling, data collection, and weighting processes are published elsewhere (10).

Statistical Analysis

We calculated the weighted and direct age-standardized prevalence estimates using BRFSS analytic recommendations published by the CDC (10, 11). Direct age standardization was based on the standard 2000 U.S. Census population using age categories of 18 to 44 years, 45 to 64 years, and 65 years or older. Furthermore, we age standardized the prevalence estimates in each subgroup to account for differences in the age composition of the subgroups. We tested for a linear trend in prevalence of e-cigarette use across 5-year age groups by using logistic regression with age group included as a continuous variable. We compared the prevalence of e-cigarette use by socioeconomic and lifestyle covariates, and chronic health conditions by using logistic regression models adjusted for age group. From these models, we found age-adjusted prevalence values (predicted margins), and we report results as absolute prevalence difference, with 95% CIs. Because of the likely interaction between e-cigarette use and cigarette smoking, as well as the high prevalence of dual use (12), analyses were repeated after stratification by combustible cigarette smoking status (never, former, or current). We estimated the number of e-cigarette users in the United States by applying the nationally representative prevalence estimates to the U.S. Census projection of the number of adults in 2016 (13).

All analyses were performed by using Stata, version 13.1 (StataCorp), and used BRFSS weights to account for the complex survey design, noncoverage, and nonresponse. We used the svy command in Stata to account for the complex design of BRFSS; the tab command to obtain direct age-standardized, weighted prevalence estimates; and the logistic command in conjunction with margins, nclom, and test postestimation commands to obtain predictive margins and prevalence difference with 95% CIs and P values (14).

Role of the Funding Source

This study was funded by the American Heart Association Tobacco Regulation and Addiction Center (A-TRAC), which is one of the Tobacco Centers of Regulatory Science of the FDA and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The funder had no role in study design, conduct, data collection, trial management, data analysis, manuscript preparation, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Results

Prevalence of E-Cigarette Use Among All U.S. Adults

The overall prevalence of current e-cigarette use was 4.5% (95% CI, 4.4% to 4.6%). Among current users, 33.5% used e-cigarettes daily. Translating these results to the entire U.S. adult population, the estimated number of current e-cigarette users was 10.8 million (3.6 million daily users).

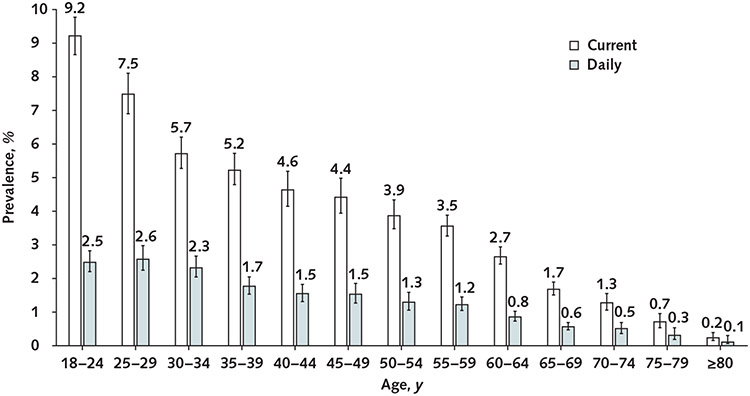

Patterns of E-Cigarette Use Across Age Groups

The median age category of current e-cigarette users was younger than that of nonusers (40 to 44 vs. 55 to 59 years, respectively [P < 0.001]). As shown in Figure 1, the prevalence of current and daily e-cigarette use decreased with increasing age. Across age groups, the prevalence of current e-cigarette use was highest among those aged 18 to 24 years (9.2% [CI, 8.6% to 9.8%]). More than half (51.2%) of all e-cigarette users were younger than 35 years.

Figure 1. Prevalence of e-cigarette use among U.S. adults, according to age group, 2016 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System survey.

P values for trends <0.001. Error bars represent 95% CIs.

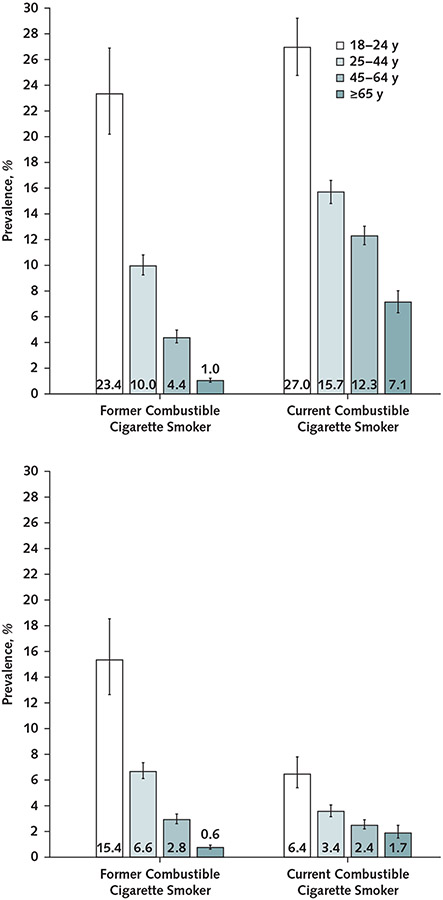

The prevalence of current e-cigarette use was highest for those aged 18 to 24 years among both current (27.0% [CI, 24.8% to 29.2%]) and former (23.4% [CI, 20.2% to 26.9%]) combustible cigarette smokers (Figure 2). The same pattern was observed among never-smokers, with the highest prevalence of current e-cigarette use among those aged 18 to 24 years (5.1% [CI, 4.6% to 5.5%]). In the 18- to 24-year age group, 44.3% of current e-cigarette users were never–combustible cigarette smokers, 38.9% were former smokers, and 16.8% were current cigarette smokers. An estimated 2.8 million adults aged 18 to 24 years were current e-cigarette users in 2016. Of these, approximately 1.2 million were never–cigarette smokers, 0.5 million were former cigarette smokers, and 1.1 million were current smokers (Appendix Table 2, available at Annals.org).

Figure 2. Prevalence of current (top) and daily (bottom) e-cigarette use among former and current combustible cigarette smokers, stratified by age, 2016 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System survey.

Error bars represent 95% CIs.

Patterns of E-Cigarette Use, by Sociodemographic Group

Table 1 shows the age-standardized prevalence of e-cigarette use across different sociodemographic groups and chronic health conditions, and Table 2 presents the age-adjusted absolute difference across these groups. The age-standardized prevalence of current e-cigarette use was higher in men (5.9% [CI, 5.6% to 6.1%]) than women (3.7% [CI, 3.6% to 3.9%]). Approximately 60.0% of current e-cigarette users were men. The prevalence of current e-cigarette use was high among lesbian or gay (7.0% [CI, 5.5% to 8.8%]), bisexual (9.0% [CI, 7.6% to 10.6%]), and transgender (8.7% [CI, 6.0% to 12.6%]) adults. Compared with persons without the respective comorbid condition, the absolute difference in age-adjusted prevalence of current e-cigarette use was 3.2% (CI, 2.3% to 4.0%) higher among participants with cardiovascular disease, 1.8% (CI, 1.1% to 2.5%) higher in those with cancer, 1.9% (CI, 1.4% to 2.4%) higher in those with asthma, 7.1% (CI, 6.2% to 8.0%) higher in those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and 4.9% (CI, 4.5% to 5.3%) higher in those with depression.

Table 1.

Age-Standardized Prevalence (95% CI) of E-Cigarette Use, Overall and by Cigarette Smoking Status (n = 466 842)*

| Variable | Overall U.S. Adult Population |

Never-Smoker of Combustible Cigarettes (n ≅ 140 Million Adults [59.3% of the U.S. Adult Population]) |

Former Smoker of Combustible Cigarettes (n ≅ 59 Million Adults [24.4% of the U.S. Adult Population]) |

Current Smoker of Combustible Cigarettes (n ≅ 39 Million Adults [16.3% of the U.S. Adult Population]) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Current E-Cigarette User (n = 15 240) |

Daily E-Cigarette User (n = 5021) |

Current E-Cigarette User (n = 1879) |

Daily E-Cigarette User (n = 375) |

Current E-Cigarette User (n = 4502) |

Daily E-Cigarette User (n = 2883) |

Current E-Cigarette User (n = 8785) |

Daily E-Cigarette User (n = 1742) |

|

| Total population | 4.5 (4.4–4.6) | 1.5 (1.4–1.6) | 1.4 (1.3–1.5) | 0.2 (0.2–0.3) | 7.6 (7.2–8.1) | 5.0 (4.6–5.3) | 14.4 (13.9–14.9) | 3.1 (2.8–3.4) |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 3.7 (3.6–3.91) | 1.1 (1.0–1.2) | 0.9 (0.8–1.0) | 0.2 (0.1–0.2) | 6.1 (5.6–6.7) | 3.8 (3.4–4.3) | 14.1 (13.4–14.8) | 2.4 (2.1–2.7) |

| Male | 5.9 (5.6–6.1) | 2.1 (1.9–2.2) | 2.0 (1.8–2.2) | 0.3 (0.3–0.4) | 8.6 (7.9–9.2) | 5.7 (5.2–6.3) | 14.5 (13.8–15.3) | 3.6 (3.2–4.0) |

| Sexual orientation † | ||||||||

| Heterosexual | 4.6 (4.4–4.8) | 1.5 (1.4–1.6) | 1.3 (1.2–1.5) | 0.2 (0.2–0.3) | 7.2 (6.6–7.9) | 4.7 (4.2–5.3) | 13.9 (13.2–14.8) | 2.9 (2.6–3.3) |

| Lesbian/gay | 7.0 (5.5–8.8) | 2.2 (1.4–3.4) | 2.6 (1.6–4.3) | 0.2 (0–1.2) | 9.7 (5.4–16.8) | 6.3 (2.9–13.3) | 15.5 (11.2–21.1) | 3.6 (1.9–6.6) |

| Bisexual | 9.0 (7.6–10.6) | 3.2 (2.3–4.4) | 3.6 (2.5–5.1) | 1.0 (0.5–2.0) | 10.5 (7.0–15.5) | 7.7 (4.5–12.8) | 19.3 (15.5–23.7) | 4.1 (2.6–6.4) |

| Gender identity † | ||||||||

| Cisgender | 4.7 (4.5–4.9) | 1.5 (1.4–1.7) | 1.4 (1.2–1.5) | 0.2 (0.2–0.3) | 7.4 (6.7–8.1) | 4.8 (4.3–5.4) | 14.3 (13.5–15.0) | 3.0 (2.6–3.3) |

| Transgender | 8.7 (6.0–12.6) | 3.5 (1.9–6.3) | 6.7 (3.7–11.9) | 2.4 (0.8–6.7) | 10.6 (4.8–21.9) | 9.3 (3.8–20.6) | 13.8 (7.6–23.6) | 2.2 (0.8–5.9) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||

| White | 5.9 (5.7–6.1) | 2.1 (2.0–2.3) | 1.5 (1.4–1.7) | 0.3 (0.3–0.4) | 8.4 (7.9–8.9) | 5.7 (5.3–6.2) | 15.9 (15.3–16.6) | 3.7 (3.3–4.0) |

| African American | 3.4 (3.1–3.8) | 0.6 (0.5–0.8) | 1.2 (1.0–1.5) | 0.1 (0.1–0.2) | 7.3 (5.4–9.7) | 3.6 (2.4–5.1) | 9.6 (8.4–10.9) | 1.0 (0.7–1.6) |

| Alaskan and Native American | 7.4 (6.0–9.0) | 2.5 (1.7–3.7) | 2.0 (1.2–3.3) | 0.3 (0.1–0.8) | 7.0 (4.7–10.2) | 5.3 (3.2–8.4) | 17.4 (13.6–21.9) | 4.6 (2.4–8.7) |

| Asian | 2.8 (2.3–3.4) | 0.8 (0.6–1.2) | 1.2 (0.8–1.7) | 0.2 (0.1–0.6) | 7.2 (4.9–10.4) | 4.2 (2.5–7.0) | 17.4 (13.4–22.1) | 3.5 (2.2–5.7) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 6.5 (4.2–10.0) | 2.1 (1.2–3.8) | 1.7 (0.8–3.3) | 0.3 (0.1–0.7) | 9.8 (4.5–20.0) | 8.2 (3.3–19.1) | 21.9 (14.4–32.1) | 4.7 (1.9–11.0) |

| Multiracial | 9.3 (7.4–11.6) | 2.4 (1.7–3.3) | 2.6 (1.8–3.8) | 0.3 (0.2–0.7) | 12.7 (7.8–19.8) | 5.6 (4.0–7.8) | 20.5 (17.0–24.6) | 4.5 (2.5–7.9) |

| Hispanic | 2.6 (2.4–2.9) | 0.7 (0.5–0.8) | 1.2 (1.0–1.4) | 0.2 (0.1–0.3) | 4.1 (3.3–5.2) | 2.3 (1.7–3.1) | 9.2 (7.9–10.7) | 1.8 (1.3–2.5) |

| Employment status | ||||||||

| Employed for wages | 4.6 (4.4–4.8) | 1.7 (1.6–1.8) | 1.3 (1.2–1.4) | 0.2 (0.2–0.3) | 7.7 (7.1–8.3) | 5.2 (4.7–5.7) | 13.9 (13.2–14.7) | 3.3 (2.9–3.7) |

| Self-employed | 4.8 (4.3–5.3) | 1.3 (1.1–1.5) | 1.2 (0.9–1.6) | 0.2 (0.1–0.3) | 6.3 (5.2–7.5) | 3.2 (2.6–4.0) | 14.3 (12.5–16.3) | 2.5 (2.0–3.2) |

| Out of work for ≥1 y | 6.0 (5.2–7.0) | 1.5 (1.1–2.1) | 1.3 (0.9–2.0) | 0.1 (0–0.3) | 8.2 (5.5–12.1) | 4.2 (2.9–6.1) | 13.6 (11.3–16.3) | 3.0 (1.8–5.1) |

| Out of work for <1 y | 7.2 (6.3–8.1) | 1.8 (1.4–2.3) | 2.5 (1.8–3.5) | 0.4 (0.2–0.8) | 9.3 (7.3–11.8) | 6.4 (4.7–8.5) | 15.7 (13.2–18.6) | 2.2 (1.5–3.3) |

| Homemaker | 2.7 (2.4–3.2) | 1.0 (0.8–1.3) | 0.2 (0.1–0.3) | 0.1 (0–0.1) | 6.1 (4.8–7.9) | 4.1 (3.0–5.7) | 12.4 (10.5–14.7) | 2.1 (1.4–3.2) |

| Student | 5.2 (3.9–6.7) | 1.7 (0.8–3.4) | 2.1 (1.8–2.5) | 0.3 (0.2–0.4) | 13.0 (9.4–17.8) | 9.2 (5.9–13.9) | 16.9 (13.5–20.8) | 3.6 (2.5–5.3) |

| Retired | 4.6 (2.8–7.6) | 1.1 (0.5–2.2) | 3.5 (1.2–9.4) | 0.5 (0.1–3.3) | 2.9 (1.3–6.6) | 2.2 (0.8–6.2) | 10.2 (6.6–15.6) | 1.5 (0.7–3.0) |

| Unable to work | 7.9 (7.2–8.7) | 2.2 (1.9–2.6) | 1.5 (1.0–2.2) | 0.5 (0.3–1.0) | 8.3 (6.7–10.3) | 5.0 (3.8–6.5) | 15.6 (14.1–17.3) | 2.7 (2.2–3.4) |

| Highest education level | ||||||||

| Less than high school diploma | 5.2 (4.8–5.7) | 1.3 (1.1–1.6) | 1.3 (1.0–1.6) | 0.2 (0.1–0.4) | 5.9 (4.6–7.6) | 4.3 (3.2–5.7) | 12.6 (11.4–13.9) | 2.0 (1.6–2.5) |

| High school diploma | 6.3 (6.0–6.6) | 2.1 (1.9–2.2) | 2.2 (1.9–2.47) | 0.5 (0.4–0.6) | 9.3 (8.4–10.3) | 5.9 (5.2–6.6) | 14.3 (13.5–15.1) | 3.2 (2.8–3.6) |

| Some college | 4.0 (3.9–4.2) | 1.4 (1.3–1.5) | 1.1 (1.0–1.3) | 0.2 (0.1–0.2) | 7.1 (6.6–7.7) | 4.7 (4.2–5.1) | 15.4 (14.7–16.3) | 3.6 (3.1–4.0) |

| Exercise during the past 30 d | ||||||||

| Yes | 4.7 (4.6–4.9) | 1.6 (1.5–1.7) | 1.4 (1.3–1.6) | 0.2 (0.1–0.3) | 7.6 (7.1–8.1) | 5.0 (4.6–5.4) | 15.4 (14.7–16.0) | 3.3 (3.0–3.7) |

| No | 5.0 (4.7–5.3) | 1.5 (1.4–1.7) | 1.3 (1.1–1.5) | 0.3 (0.2–0.4) | 7.7 (6.7–8.9) | 4.7 (4.0–5.6) | 12.1 (11.3–13.0) | 2.5 (2.1–2.9) |

| Body mass index | ||||||||

| <18.5 kg/m2 | 6.6 (5.6–7.7) | 2.1 (1.6–2.7) | 2.0 (1.4–2.9) | 0.4 (0.2–0.9) | 13.8 (9.9–18.9) | 8.2 (5.8–11.5) | 15.4 (12.6–18.8) | 3.4 (2.1–5.6) |

| 18.5–24.9 kg/m2 | 5.2 (5.0–5.5) | 1.6 (1.5–1.7) | 1.6 (1.4–1.8) | 0.2 (0.2–0.3) | 9.0 (8.2–9.9) | 5.7 (5.0–6.4) | 15.2 (14.4–16.2) | 3.2 (2.8–3.7) |

| 25–29.9 kg/m2 | 4.7 (4.5–5.0) | 1.6 (1.4–1.7) | 1.5 (1.3–1.7) | 0.3 (0.2–0.4) | 6.8 (6.1–7.5) | 4.4 (3.8–4.9) | 13.8 (13.0–14.8) | 3.2 (2.7–3.7) |

| ≥30 kg/m2 | 4.9 (4.6–5.2) | 1.8 (1.6–1.9) | 1.3 (1.1–1.5) | 0.2 (0.1–0.4) | 7.7 (6.9–8.7) | 5.3 (4.6–6.1) | 14.2 (13.2–15.2) | 3.1 (2.6–3.6) |

| Federal poverty line ratio of household income | ||||||||

| <1 | 5.0 (4.7–5.4) | 1.3 (1.1–1.4) | 1.4 (1.1–1.6) | 0.2 (0.1–0.3) | 6.6 (5.5–7.9) | 3.9 (3.3–4.6) | 12.8 (11.8–13.9) | 2.4 (1.9–2.9) |

| 1–2 | 5.8 (5.4–6.1) | 1.8 (1.7–2.0) | 1.4 (1.2–1.7) | 0.3 (0.2–0.5) | 8.6 (7.6–9.8) | 5.6 (4.7–6.5) | 14.6 (13.7–15.7) | 3.1 (2.6–3.6) |

| >2 | 4.4 (4.3–4.6) | 1.6 (1.5–1.7) | 1.4 (1.3–1.5) | 0.2 (0.2–0.3) | 7.6 (7.0–8.1) | 5.1 (4.6–5.5) | 14.8 (14.1–15.6) | 3.5 (3.1–3.9) |

| Pregnant | 1.9 (1.2–2.9) | 0.5 (0.2–1.1) | 0.7 (0.2–1.9) | 0 (0–0.2) | 3.1 (1.4–6.6) | 1.5 (0.6–3.8) | 11.1 (6.2–19.2) | 3.1 (0.9–10.4) |

| Consumption of ≥1 alcoholic drink during the past 30 d | ||||||||

| No | 3.9 (3.7–4.2) | 1.4 (1.3–1.5) | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 0.2 (0.1–0.3) | 7.6 (6.8–8.3) | 5.3 (4.7–5.9) | 14.2 (13.3–15.1) | 3.1 (2.7–3.5) |

| Yes | 5.5 (5.3–5.7) | 1.7 (1.6–1.8) | 1.8 (1.7–2.0) | 0.3 (0.2–0.3) | 7.6 (7.1–8.2) | 4.8 (4.4–5.3) | 14.6 (13.9–15.3) | 3.1 (2.7–3.4) |

| Relationship status | ||||||||

| Not partnered | 6.0 (5.8–6.3) | 1.8 (1.7–1.9) | 2.2 (2.0–2.3) | 0.4 (0.3–0.5) | 9.4 (8.6–10.2) | 6.2 (5.5–6.9) | 15.0 (14.3–15.7) | 3.1 (2.8–3.5) |

| Partnered | 3.7 (3.5–3.9) | 1.4 (1.3–1.5) | 0.6 (0.5–0.7) | 0.1 (0.1–0.1) | 6.5 (5.9–7.0) | 4.2 (3.8–4.6) | 13.5 (12.8–14.3) | 3.0 (2.6–3.5) |

| Cardiovascular disease | ||||||||

| No | 4.7 (4.5–4.8) | 1.5 (1.4–1.6) | 1.4 (1.3–1.5) | 0.2 (0.2–0.3) | 7.6 (7.1–8.0) | 5.0 (4.6–5.3) | 14.2 (13.7–14.8) | 3.0 (2.8–3.3) |

| Yes | 7.0 (6.0–8.2) | 2.0 (1.6–2.6) | 0.9 (0.6–1.6) | 0.3 (0.1–1.0) | 7.2 (5.3–9.7) | 4.5 (3.1–6.3) | 15.7 (13.2–18.7) | 2.9 (2.1–4.1) |

| Diabetes status | ||||||||

| No | 4.8 (4.7–5.0) | 1.6 (1.5–1.7) | 1.4 (1.3–1.5) | 0.2 (0.2–0.3) | 7.8 (7.4–8.3) | 5.1 (4.7–5.5) | 14.3 (13.7–14.8) | 3.1 (2.8–3.3) |

| Prediabetes | 4.9 (3.8–6.4) | 1.3 (0.8–2.0) | 1.3 (0.6–2.5) | 0.4 (0.1–1.9) | 2.9 (1.6–5.2) | 2.0 (0.9–4.3) | 17.7 (13.4–23.1) | 3.1 (1.8–5.6) |

| Diabetes | 5.0 (4.4–5.7) | 1.6 (1.2–2.0) | 1.3 (0.8–1.9) | 0.5 (0.2–1.0) | 4.5 (3.5–5.7) | 2.8 (2.1–3.8) | 15.2 (13.2–17.5) | 3.1 (2.2–4.3) |

| Cancer | ||||||||

| No | 4.8 (4.6–4.9) | 1.6 (1.5–1.7) | 1.4 (1.3–1.5) | 0.2 (0.2–0.3) | 7.6 (7.2–8.1) | 5.0 (4.6–5.4) | 14.2 (13.7–14.8) | 3.1 (2.8–3.3) |

| Yes | 6.5 (5.6–7.5) | 1.7 (1.3–2.4) | 0.5 (0.3–1.0) | 0.2 (0–0.7) | 7.7 (5.4–10.8) | 4.2 (2.4–7.2) | 17.4 (15.2–19.9) | 3.0 (2.2–4.1) |

| Asthma | ||||||||

| No | 4.6 (4.5–4.8) | 1.5 (1.4–1.6) | 1.4 (1.3–1.5) | 0.2 (0.1–0.3) | 7.6 (7.2–8.1) | 5.0 (4.6–5.4) | 13.7 (13.2–14.3) | 3.0 (2.7–3.3) |

| Yes | 6.7 (6.2–7.2) | 1.8 (1.5–2.1) | 2.1 (1.7–2.5) | 0.5 (0.3–0.7) | 6.6 (5.4–8.0) | 4.4 (3.3–5.7) | 19.1 (17.6–20.8) | 3.5 (2.8–4.4) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | ||||||||

| No | 4.5 (4.4–4.6) | 1.5 (1.4–1.6) | 1.4 (1.3–1.5) | 0.2 (0.2–0.3) | 7.5 (7.0–7.9) | 4.9 (4.5–5.3) | 13.9 (13.4–14.5) | 3.0 (2.8–3.3) |

| Yes | 10.2 (9.2–11.2) | 2.6 (2.2–3.1) | 2.3 (1.6–3.4) | 0.7 (0.3–1.6) | 9.1 (6.7–12.2) | 4.9 (3.4–6.9) | 16.8 (15.2–18.6) | 3.1 (2.5–3.8) |

| Depression | ||||||||

| No | 3.9 (3.8–4.1) | 1.3 (1.1–1.3) | 1.3 (1.2–1.4) | 0.2 (0.1–0.3) | 6.8 (6.3–7.3) | 4.3 (3.9–4.7) | 12.5 (11.9–13.2) | 2.7 (2.3–2.9) |

| Yes | 9.1 (8.7–9.5) | 3.1 (2.9–3.4) | 2.3 (2.04–2.7) | 0.5 (0.4–0.7) | 10.5 (9.5–11.6) | 7.3 (6.5–8.2) | 19.0 (18.0–20.1) | 4.3 (3.7–4.9) |

| Chronic kidney disease | ||||||||

| No | 4.8 (4.6–4.9) | 1.6 (1.5–1.6) | 1.4 (1.3–1.5) | 0.2 (0.2–0.3) | 7.6 (7.1–8.0) | 4.9 (4.5–5.3) | 14.3 (13.8–14.9) | 3.1 (2.8–3.3) |

| Yes | 6.5 (5.3–8.0) | 3.1 (2.2–4.5) | 1.5 (0.7–2.9) | 0.6 (0.2–1.9) | 10.2 (6.5–15.6) | 8.4 (5.0–14.0) | 15.5 (12.7–18.9) | 4.3 (2.8–6.7) |

Values are prevalences (95% CIs) presented as percentages.

Asked in the following states and territories: California, Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, Guam, Hawaii, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Nevada, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Texas, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, and Wisconsin.

Table 2.

Age-Adjusted Absolute Prevalence Difference (95% CI) for E-Cigarette Use Among Demographic and Socioeconomic Groups*

| Variable | Current E-Cigarette User |

Daily E-Cigarette User |

|---|---|---|

| Combustible cigarette smoking status | ||

| Never | 0.0 (reference) | 0.0 (reference) |

| Current | 12.8 (12.3 to 13.3) | 2.8 (2.5 to 3.0) |

| Former | 6.6 (6.1 to 7.0) | 4.9 (4.5 to 5.3) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 0.0 (reference) | 0.0 (reference) |

| Female | −1.8 (−2.1 to −1.6) | −0.9 (−0.1 to −0.7) |

| Age † | ||

| 18–24 y | 0.0 (reference) | 0.0 (reference) |

| 25–29 y | −1.7 (−2.5 to −0.9) | 0.1 (−0.4 to 0.6) |

| 30–34 y | −3.5 (−4.2 to −2.7) | −0.2 (−0.6 to 0.3) |

| 35–39 y | −4.0 (−4.7 to −3.2) | −0.7 (−1.1 to −0.3) |

| 40–44 y | −4.6 (−5.3 to −3.8) | −0.9 (−1.3 to −0.5) |

| 45–49 y | −4.8 (−5.5 to −4.0) | −1.0 (−1.4 to −0.5) |

| 50–54 y | −5.2 (−6.0 to −4.6) | −1.2 (−1.6 to −0.8) |

| 55–59 y | −5.6 (−6.3 to −5.0) | −1.3 (−1.6 to −0.9) |

| 60–64 y | −6.5 (−7.1 to −5.9) | −1.6 (−2.0 to −1.3) |

| 65–69 y | −7.5 (−8.1 to −6.9) | −1.9 (−2.2 to −1.6) |

| 70–74 y | −7.9 (−8.5 to −7.3) | −2.0 (−2.3 to −1.6) |

| 75–79 y | −8.5 (−9.1 to −7.9) | −2.2 (−2.5 to −1.8) |

| ≥80 y | −9.0 (−9.5 to −8.4) | −2.4 (−2.7 to −2.1) |

| Sexual orientation ‡ | ||

| Heterosexual | 0.0 (reference) | 0.0 (reference) |

| Lesbian/gay | 1.9 (0.4 to 3.4) | 0.6 (−0.3 to 1.4) |

| Bisexual | 3.6 (2.2 to 4.9) | 1.5 (0.5 to 2.5) |

| Gender identity ‡ | ||

| Cisgender | 0.0 (reference) | 0.0 (reference) |

| Transgender | 3.2 (0.38 to 6.1) | 1.7 (−0.2 to 3.5) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | 0.0 (reference) | 0.0 (reference) |

| African American | −2.3 (−2.7 to −1.9) | −1.4 (−1.6 to −1.8) |

| Alaskan and Native American | 1.3 (0 to 2.7) | 0.3 (−0.5 to 1.2) |

| Asian | −2.9 (−3.5 to −2.4) | −1.2 (−1.6 to −0.9) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | −0.1 (−2.0 to 1.8) | 0.1 (−1.2 to 1.1) |

| Multiracial | 2.8 (0.1 to 4.6) | 0.1 (−0.6 to 0.8) |

| Hispanic | −3.0 (−3.4 to −2.7) | −1.4 (−1.5 to −1.2) |

| Employment status | ||

| Employed forwages | 0.0 (reference) | 0.0 (reference) |

| Self-employed | 0.4 (−0.1 to 0.9) | −0.4 (−0.6 to −0.1) |

| Out of work for ≥1 y | 1.4 (0.5 to 2.2) | −0.2 (−0.6 to 0.2) |

| Out of work for <1 y | 1.9 (1.1 to 2.7) | 0.1 (−0.3 to 0.5) |

| Homemaker | −1.4 (−1.9 to −1.0) | −0.6 (−0.9 to −0.3) |

| Student | −1.4 (−1.8 to −0.9) | −0.7 (−1.0 to −0.5) |

| Retired | 0.9 (0.2 to 1.5) | 0 (−0.4 to 0.3) |

| Unable to work | 4.5 (3.8 to 5.3) | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.4) |

| Income | ||

| Below the poverty line | 0.0 (reference) | 0.0 (reference) |

| Within 100%–200% of the poverty line | 0.8 (0.3 to 1.2) | 0.6 (0.3 to 0.8) |

| >200% of the poverty line | −0.5 (−0.9 to −0.1) | 0.3 (0.1 to 0.5) |

| Highest education level | ||

| Less than high school diploma | 0.0 (reference) | 0.0 (reference) |

| High school diploma | 0.6 (0 to 1.1) | 0.6 (0.4 to 0.9) |

| Some college | −1.3 (−1.8 to −0.8) | 0 (−0.2 to 0.2) |

| Exercise during the past 30 d | ||

| No | 0.0 (reference) | 0.0 (reference) |

| Yes | −0.6 (−1.0 to −0.3) | −0.1 (−0.3 to 0.1) |

| Body mass index | ||

| <18.5 kg/m2 | 0.0 (reference) | 0.0 (reference) |

| 18.5–24.9 kg/m2 | −0.7 (−1.6 to 0.2) | −0.3 (−0.8 to 0.2) |

| 25–29.9 kg/m2 | −0.9 (−1.8 to 0) | −0.2 (−0.7 to 0.3) |

| ≥30 kg/m2 | −0.7 (−1.6 to 0.2) | −0.1 (−0.6 to 0.4) |

| Relationship status | ||

| Not partnered | 0.0 (reference) | 0.0 (reference) |

| Partnered | −1.8 (−2.1 to −1.5) | −0.3 (−0.5 to −0.2) |

| Consumption of 1 alcoholic drink during the past 30 d | ||

| No | 0.0 (reference) | 0.0 (reference) |

| Yes | 1.3 (1.1 to 1.6) | 0.3 (0.1 to 0.4) |

| Cardiovascular disease | ||

| No | 0.0 (reference) | 0.0 (reference) |

| Yes | 3.2 (2.3 to 4.0) | 0.9 (0.5 to 1.4) |

| Diabetes status | ||

| No | 0.0 (reference) | 0.0 (reference) |

| Prediabetes | 0 (−1.0 to 1.0) | −0.4 (−0.8 to 0.1) |

| Diabetes | 0.6 (0.1 to 1.2) | 0.2 (−0.2 to 0.5) |

| Cancer | ||

| No | 0.0 (reference) | 0.0 (reference) |

| Yes | 1.8 (1.1 to 2.5) | 0.4 (0 to 0.9) |

| Asthma | ||

| No | 0.0 (reference) | 0.0 (reference) |

| Yes | 1.9 (1.4 to 2.4) | 0.2 (0 to 0.5) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | ||

| No | 0.0 (reference) | 0.0 (reference) |

| Yes | 7.1 (6.2 to 8.0) | 0.2 (0.1 to 0.2) |

| Depression | ||

| No | 0.0 (reference) | 0.0 (reference) |

| Yes | 4.9 (4.5 to 5.3) | 1.8 (1.5 to 2.0) |

| Chronic kidney disease | ||

| No | 0.0 (reference) | 0.0 (reference) |

| Yes | 1.9 (0.9 to 3.0) | 1.2 (0.4 to 2.0) |

Values are prevalence differences (95% CIs) presented as percentage points.

Values were not adjusted with age.

Asked in the following states and territories: California, Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, Guam, Hawaii, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Nevada, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Texas, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, and Wisconsin.

Patterns of E-Cigarette Use, by Combustible Cigarette Smoking Status

As shown in Table 1, e-cigarette use was consistently more prevalent among former and current cigarette users than never-smokers. Overall, the age-standardized prevalence of current e-cigarette use was 1.4% (CI, 1.3% to 1.5%) among never-, 7.6% (CI, 7.2% to 8.1%) among former, and 14.4% (CI, 13.9% to 14.9%) among current smokers. The prevalence of daily e-cigarette use, however, was highest among former cigarette smokers (5.0% [CI, 4.6% to 5.3%]), followed by current (3.1% [CI, 2.8% to 3.4%]) and never–combustible cigarette smokers (0.2% [CI, 0.2% to 0.3%]). Of the current e-cigarette users, 15% were never–cigarette smokers, 30.4 were former-cigarette smokers, and 54.6% were current-cigarette smokers.

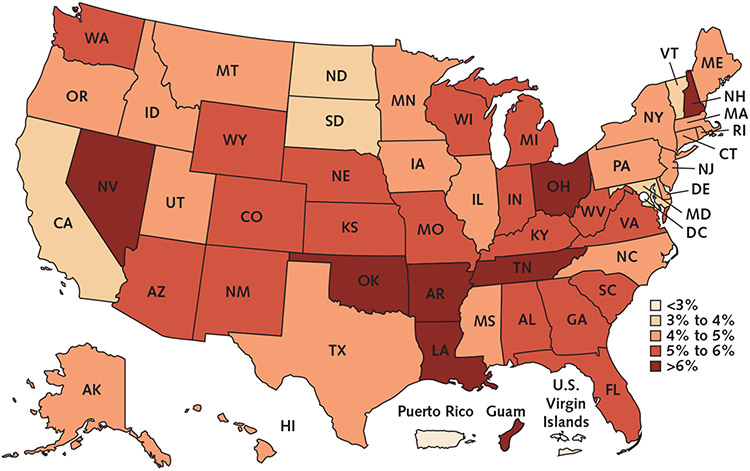

Prevalence of E-Cigarette Use Among U.S. Adults, by State

Figure 3 and Appendix Table 3 (available at Annals.org) show the state-specific, age-standardized prevalence of e-cigarette use. All southern and western states had a high prevalence of current e-cigarette use, except for California (3.3% [CI, 2.9% to 3.8%]). The prevalence of e-cigarette use in the midwest region varied markedly, from 3.0% (CI, 2.3% to 4.0%) in South Dakota to 6.2% (CI, 5.4% to 7.0%) in Ohio. In most northeastern states, the prevalence of current e-cigarette use was low, except in New Hampshire (6.1% [CI, 5.0% to 7.5%]).

Figure 3. State-specific, age-standardized prevalence of current e-cigarette use among U.S. adults: results of the 2016 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System survey.

Discussion

Here we report the prevalence and distribution of e-cigarette use in a large representative sample of the U.S. population. We provide the first 2016 data regarding the prevalence of e-cigarette use on the national and state levels. We report that 4.5% of U.S. adults (projected to 10.8 million in the total U.S. adult population) were current e-cigarette users in 2016. Of importance, adults younger than 35 years accounted for more than half of all e-cigarette users in the United States. In addition, we observed that current e-cigarette use was highly prevalent among men; lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender persons; those who were unemployed; and those with chronic disease.

Our estimates of e-cigarette use differ from those of studies conducted between 2013 and 2014. For example, on the basis of data from the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), the CDC reported that the prevalence of current e-cigarette use (defined as use every day or some days) among U.S. adults in 2014 was 3.7%, which is about 0.8% lower than our estimate (15). The PATH (Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health) study reported a 5.5% prevalence of current e-cigarette use in 2013 to 2014 (12, 16), whereas the NHANES (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey) for 2013 to 2014 reported prevalence estimates of 2.6% (17).

The heterogeneity in prevalence estimates among the U.S. studies is probably the result of differences in data collection methods and classification of current e-cigarette use across these studies. For example, whereas participants in NHANES 2013 to 2014 were asked about the use of e-cigarettes in the past 5 days, the PATH study had a more detailed assessment of product use, including recent use during the past 30 days (12). The lower prevalence estimates in our study versus those of PATH may be a function of differences in the year of collection of surveys, or they may be related to the BRFSS sampling process, which ensured adequate representation of minority groups and older adults, a subgroup with a lower prevalence of e-cigarette use in our study. Given these notable differences in data collection methods and resulting estimates, additional studies using consistent e-cigarette use questions are needed to assess future changes in the prevalence of e-cigarette use in the United States.

Consistent with our findings, data from NHANES and PATH show that e-cigarette use among U.S. adults was most prevalent among younger persons (12, 16, 17). We estimated that 2.8 million younger adults (1.2 million of whom were never-smokers) were current e-cigarette users in 2016. Our data emphasize the high prevalence of e-cigarette use among younger age groups. Particularly notable is the emergence of a high prevalence of e-cigarette use among younger adults who never smoked combustible cigarettes. In addition to the potential health hazard of e-cigarettes, including exposure to volatile organic compounds (18), e-cigarette use in younger ages may serve as a gateway to cigarette smoking (19).

Since the introduction of e-cigarettes in the United States, their potential utility as smoking cessation devices has been at the forefront of public health discussions (20, 21). Our results suggest that persons who never smoked cigarettes use e-cigarettes; we report that 15% of all e-cigarette users (an estimated 1.9 million U.S. adults) were never–cigarette smokers. Detailed data on the characteristics of this population are scarce, and future research is required to understand why e-cigarettes appeal to this tobacco-naive population. Moreover, the size of this population should be monitored over time, given that our study uses only a single time point.

From a research perspective, e-cigarette users who never smoked cigarettes are the only group available in which to study the unique health effects of e-cigarette use (without confounding from combustible cigarette smoking). Furthermore, knowledge of the size of the never-smoking, e-cigarette–using population is especially important for regulatory authorities, in light of the recent FDA decision to decrease the nicotine content of combustible cigarettes. The FDA projects that this decision will lead many persons to switch to noncombustible tobacco products, including e-cigarettes (22). Our study thus provides a benchmark for future studies that aim to assess the effect of these policy changes.

Consistent with previous reports (2, 23), our findings revealed that most e-cigarette users also smoke combustible cigarettes (dual tobacco use). In our analysis, we found that 54.6% of current e-cigarette users also were current combustible cigarette smokers. In agreement with these findings, PATH, NHANES, and NHIS have indicated that e-cigarette users are more likely to be current or former combustible cigarette smokers (15-17, 23). However, lack of temporality in cross-sectional studies restricts our ability to infer the order in which these tobacco habits were adopted. For example, some studies have suggested that these data support the notion that e-cigarettes are being used as smoking cessation devices (24), whereas others have stated that dual use increases exposure to nicotine and may perpetuate abuse liability instead of encouraging smoking cessation (25, 26).

Our study also reports—for the first time, we believe—the prevalence of e-cigarette use by state of residence in 2016. Previously, the PATH study's results showed that e-cigarette use was more prevalent in midwestern and southern regions (12). Our analyses of the BRFSS survey, however, provide a more extensive assessment of statewide e-cigarette prevalence. We found that the prevalence of e-cigarette use differed among western, midwestern, and eastern states. The reasons for such marked differences remain understudied and may include such factors as socioeconomic status, tobacco laws, and taxation, all warranting further investigation to inform policy and educational initiatives on e-cigarette use.

The primary strength of our study is that, to our knowledge, it is the largest and most current survey to report the nationwide prevalence of e-cigarette use. In addition, our study reports prevalence estimates in different socioeconomic groups, as well as among persons with chronic health conditions. Nonetheless, the study has some notable limitations. First, no standard measurements exist to define the intensity or burden of e-cigarette use. Second, the BRFSS does not have any directly measured risk factor data, because all information was obtained from self-report. For example, the BRFSS lacks information about biochemical measures of tobacco use (namely urinary cotinine); type of e-cigarette delivery mechanism (for example, tank, mod, or voltage pen); and type of e-cigarette liquid, including nicotine dose or flavors. Third, sexual orientation and gender identity were assessed in only a subset of states. However, the BRFSS weighting process was used to ensure that results were nationally representative. Finally, BRFSS data are cross-sectional, so we cannot infer the temporality of association between e-cigarette use and any of the demographic characteristics examined.

In conclusion, we believe our study provides the most up-to-date and detailed national and state-level prevalence estimates of e-cigarette use in a nationally representative survey of the United States. These data will help inform health care policymakers about the size and characteristics of the e-cigarette–using population; facilitate monitoring of temporal trends in use patterns; and guide future research efforts, public education campaigns, and tobacco regulatory policy.

Grant Support:

By A-TRAC grant 1P50HL120163.

Appendix

Appendix Table 1.

Study Population for the Whole Population and Each Subgroup, 2016 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System*

| Variable | Current (n = 15 240) |

Daily (n = 5021) |

Total (n = 466 842) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (missing n = 51) | |||

| Male | 7823 | 2782 | 201 991 |

| Female | 7414 | 2236 | 264 800 |

| Age (missing n = 5788) | |||

| 18-24 y | 2328 | 642 | 25 345 |

| 25-29 y | 1502 | 513 | 21 885 |

| 30-34 y | 1430 | 517 | 24 248 |

| 35-39 y | 1300 | 459 | 26 000 |

| 40-44 y | 1110 | 409 | 26 025 |

| 45-49 y | 1253 | 402 | 31 649 |

| 50-54 y | 1483 | 480 | 40 195 |

| 55-59 y | 1637 | 497 | 48 014 |

| 60-64 y | 1352 | 451 | 52 927 |

| 65-69 y | 940 | 315 | 54 048 |

| 70-74 y | 527 | 198 | 42 271 |

| 75-79 y | 191 | 67 | 30 397 |

| ≥80 y | 85 | 31 | 38 050 |

| Sexual orientation (missing n = 30 168) † | |||

| Heterosexual | 6043 | 2014 | 191 247 |

| Lesbian/gay | 192 | 69 | 3038 |

| Bisexual | 304 | 93 | 3416 |

| Gender identity (missing n = 32 146) † | |||

| Cisgender | 6548 | 2166 | 201 031 |

| Transgender | 54 | 25 | 779 |

| Race/ethnicity (missing n = 9834) | |||

| White | 11 811 | 4117 | 355 640 |

| African American | 890 | 173 | 37 247 |

| Alaskan and Native American | 316 | 87 | 6854 |

| Asian | 275 | 95 | 9761 |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 83 | 28 | 1367 |

| Multiracial | 565 | 161 | 9104 |

| Hispanic | 992 | 256 | 37 035 |

| Employment status (missing n = 3109) | |||

| Employed for wages | 7152 | 2495 | 188 107 |

| Self-employed | 1242 | 402 | 39 871 |

| Out of work for ≥1 y | 579 | 155 | 9368 |

| Out of work for <1 y | 658 | 179 | 9114 |

| Homemaker | 611 | 195 | 26 087 |

| Student | 753 | 186 | 11 980 |

| Retired | 1780 | 628 | 143 704 |

| Unable to work | 2359 | 738 | 35 502 |

| Education (missing n = 1353) | |||

| Less than high school diploma | 1556 | 466 | 35 839 |

| High school diploma | 5448 | 1800 | 130 479 |

| Some college | 8210 | 2745 | 299 171 |

| Exercise during past 30 days (missing n = 103 017) | |||

| Yes | 10 956 | 3608 | 347 656 |

| No | 4260 | 98 042 | 16 169 |

| Body mass index (missing n = 30 067) | |||

| <18.5 kg/m2 | 414 | 130 | 7311 |

| 18.5 to <25 kg/m2 | 5134 | 1586 | 138 730 |

| 25 to <30 kg/m2 | 4764 | 1584 | 157 618 |

| ≥30 kg/m2 | 4341 | 1534 | 133 116 |

| Alcohol use (missing n = 6089) | |||

| Yes | 8713 | 2738 | 237 262 |

| No | 6319 | 2210 | 223 491 |

| Income (missing n = 8573) | |||

| Below poverty line | 2597 | 723 | 46 232 |

| Within 100% to 200% of poverty line | 4045 | 1289 | 98 337 |

| >200% of poverty line | 8142 | 2890 | 313 700 |

| Relationship status (missing n = 2775) | |||

| Without a partner | 8667 | 2642 | 205 722 |

| With partner | 6495 | 2356 | 258 345 |

| Pregnant (missing n = 211) ‡ | 40 | 11 | 2453 |

| No | 13 361 | 4428 | 406 482 |

| Yes | 1730 | 555 | 56 345 |

| Diabetes (missing n = 749) | |||

| No | 13 443 | 4462 | 393 878 |

| Prediabetes | 260 | 76 | 8549 |

| Diabetes | 1502 | 474 | 63 666 |

| Cancer (missing n = 1051) | |||

| No | 14 022 | 4658 | 419 933 |

| Yes | 1163 | 350 | 45 858 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (missing n = 2046) | |||

| No | 12 628 | 4232 | 425 527 |

| Yes | 2517 | 765 | 39 269 |

| Asthma (missing n = 1317) | |||

| No | 12 142 | 4089 | 402 247 |

| Yes | 3043 | 915 | 63 278 |

| Depression (missing n = 1871) | |||

| No | 9770 | 3179 | 382 273 |

| Yes | 5387 | 1816 | 82 698 |

| Chronic kidney disease (missing n = 1508) | |||

| No | 14 657 | 4823 | 447 579 |

| Yes | 520 | 177 | 17 755 |

Missing n = 19 461. Values are numbers.

Asked in only 26 states (total population = 234 147).

Asked of those who identified their gender as women and were younger than 44 y.

Appendix Table 2.

Estimated Absolute Number of U.S. Adult E-Cigarette Users, According to Cigarette Smoking Status, Using the U.S. Census Estimates of the Number of U.S. Adults in 2016*

| Variable | Never-Combustible Cigarette Smoker |

Former Combustible Cigarette Smoker |

Current Combustible Cigarette Smoker |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current E-Cigarette User (n = 1 973 051) |

Daily E-Cigarette User (n = 348 595) |

Current E-Cigarette User (n = 3 083 815) |

Daily E-Cigarette User (n = 1 990 254) |

Current E-Cigarette User (n = 5 714 188) |

Daily E-Cigarette User (n = 1 219 344) |

|

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 690 684 | 133 265 | 1 133 748 | 699 418 | 2 485 962 | 430 401 |

| Male | 1 279 210 | 212 173 | 1 950 067 | 1 290 836 | 3 227 564 | 788 282 |

| Age group | ||||||

| 18-24 y | 1 235 019 | 196 424 | 466 788 | 306 672 | 1 083 556 | 255 168 |

| 25-44 y | 609 956 | 121 283 | 1 489 057 | 979 394 | 2 479 900 | 533 844 |

| 45-64 y | 99 352 | 22 537 | 919 728 | 583 252 | 1 824 446 | 348 374 |

| ≥65 y | 20 535 | 2023 | 199 475 | 115 390 | 291 318 | 70 078 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| White | 1 074 390 | 226 544 | 2 393 609 | 1 607 532 | 4 156 417 | 944 900 |

| African American | 235 565 | 21 443 | 188 136 | 102 854 | 505 592 | 58 520 |

| Alaskan and Native American | 20 144 | 3354 | 32 565 | 24 814 | 106 664 | 25 707 |

| Asian | 134 577 | 25 351 | 83 457 | 49 977 | 144 033 | 31 353 |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 6222 | 1551 | 6697 | 5615 | 16 518 | 3695 |

| Multiracial | 57 403 | 6453 | 89 214 | 36 498 | 185 390 | 40 478 |

| Hispanic | 402 377 | 53 874 | 248 611 | 138 307 | 489 267 | 94 103 |

| Employment status | ||||||

| Employed for wages | 1 054 413 | 208 504 | 1 810 811 | 1 225 778 | 2 887 203 | 678 839 |

| Self-employed | 131 565 | 22 045 | 263 459 | 130 469 | 536 718 | 93 332 |

| Out of work for ≥1 y | 41 517 | 2334 | 72 670 | 37 284 | 257 273 | 50 948 |

| Out of work for <1 y | 119 208 | 20 276 | 108 388 | 73 929 | 321 744 | 48 591 |

| Homemaker | 22 635 | 5247 | 148 584 | 101 743 | 245 932 | 42 905 |

| Student | 480 692 | 55 224 | 151 232 | 105 219 | 243 886 | 58 356 |

| Retired | 35 532 | 5279 | 222 608 | 128 941 | 359 823 | 76 859 |

| Unable to work | 64 220 | 21 845 | 293 482 | 178 511 | 821 394 | 153 676 |

| Education | ||||||

| Less than high school diploma | 208 827 | 38 981 | 296 090 | 195 327 | 1 074 624 | 176 348 |

| High school diploma | 762 012 | 166 748 | 1 035 525 | 660 654 | 2 049 180 | 455 440 |

| Some college | 999 397 | 142 866 | 1 748 040 | 1 131 352 | 2 586 554 | 586 542 |

| Exercise during past 30 d | ||||||

| Yes | 1 649 708 | 270 483 | 2 422 512 | 1 573 941 | 4 170 381 | 907 165 |

| No | 321 067 | 77 515 | 658 267 | 414 860 | 1 541 719 | 311 426 |

| Body mass index | ||||||

| <18.5 kg/m2 | 71 021 | 13 048 | 71 270 | 43 401 | 151 823 | 33 804 |

| 18.5 to <25 kg/m2 | 815 044 | 127 293 | 1 003 861 | 621 763 | 2 018 601 | 424 533 |

| 25 to <30 kg/m2 | 595 887 | 113 370 | 979 425 | 627 033 | 1 733 248 | 386 234 |

| ≥30 kg/m2 | 418 308 | 79 271 | 935 158 | 637 640 | 1 574 489 | 328 389 |

| Income according to federal poverty line | ||||||

| Below poverty line | 314 056 | 44 846 | 343 455 | 198 074 | 1 134 676 | 207 063 |

| 100% to 200% of poverty line | 355 782 | 81 282 | 650 374 | 417 204 | 1 504 035 | 314 512 |

| >200% of poverty line | 1 191 488 | 213 519 | 2 003 832 | 1322 183 | 2 842 240 | 661 622 |

| Pregnant | 11 811 | 411 | 12 789 | 6136 | 18 280 | 5189 |

| Alcohol use | ||||||

| No | 639 694 | 152 893 | 1 097 976 | 737 398 | 2 150 306 | 472 104 |

| Yes | 1 312 789 | 190 873 | 1 944 578 | 1 220 561 | 3 487 092 | 730 797 |

| Relationship status | ||||||

| With partner | 1 534 762 | 269 723 | 1 390 936 | 916 567 | 3 377 407 | 694 932 |

| Without partner | 430 532 | 75 872 | 1 678 539 | 1061 681 | 2 303 524 | 518 339 |

| Cardiovascular disease | ||||||

| No | 1 938 057 | 338 793 | 2 827 676 | 1 841 013 | 5 093 505 | 1 086 346 |

| Yes | 26 540 | 7144 | 237 932 | 139 647 | 551 279 | 122 080 |

| Diabetes | ||||||

| Normal | 1 891 495 | 326 336 | 2 854 213 | 1 839 856 | 5 083 686 | 1 088 900 |

| Prediabetes | 17 488 | 5 887 | 24 773 | 11 020 | 103 366 | 19 726 |

| Diabetes | 61 957 | 15 924 | 203 293 | 138 460 | 505 672 | 108 592 |

| Cancer | ||||||

| No | 1 955 647 | 345 235 | 2 927 648 | 1 900 068 | 5 327 109 | 1 139 086 |

| Yes | 14 045 | 3360 | 147 043 | 86 500 | 363 567 | 78 308 |

| Asthma | ||||||

| No | 1 724 006 | 293 297 | 2 800 233 | 1 810 535 | 4 778 410 | 1 045 479 |

| Yes | 237 709 | 51 364 | 246 245 | 160 757 | 863 635 | 155 611 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | ||||||

| No | 1 909 455 | 329 469 | 2 778 662 | 1 818 287 | 4 822 017 | 1 051 734 |

| Yes | 58 113 | 18 334 | 292 194 | 161 953 | 852 527 | 163 040 |

| Depression | ||||||

| No | 1 573 950 | 255 906 | 2 155 048 | 1 340 416 | 3 482 858 | 732 147 |

| Yes | 393 128 | 90 946 | 903 447 | 630 020 | 2 204 346 | 483 828 |

| Chronic kidney disease | ||||||

| No | 1 945 621 | 336 392 | 298 6416 | 1 921 698 | 5 514 183 | 1 164 221 |

| Yes | 24 753 | 9955 | 86 934 | 60 018 | 175 669 | 53 884 |

Values are numbers.

Appendix Table 3.

State-Specific, Age-Standardized Prevalence of E-Cigarette Use Among U.S. Adults, According to the 2016 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System

| State/Territory | Weighted and Age-Standardized Prevalence, % |

|

|---|---|---|

| Current E-Cigarette Use |

Daily E-Cigarette Use |

|

| Guam | 7.2 (5.5-9.4) | 2.8 (1.8-4.4) |

| Oklahoma | 7.0 (6.0-8.2) | 2.9 (2.2-3.6) |

| Nevada | 6.4 (5.2-7.7) | 2.6 (1.9-3.5) |

| Arkansas | 6.2 (4.9-7.8) | 2.2 (1.5-3.2) |

| Tennessee | 6.2 (5.2-7.3) | 2.3 (1.7-3.1) |

| Ohio | 6.2 (5.4-7.0) | 1.8 (1.4-2.3) |

| New Hampshire | 6.1 (5.0-7.5) | 2.1 (1.4-2.9) |

| Louisiana | 6.1 (4.9-7.5) | 1.9 (1.2-2.7) |

| Wyoming | 5.9 (4.8-7.5) | 2.1 (1.4-3.1) |

| Kentucky | 5.9 (5.2-6.8) | 2.3 (1.8-2.8) |

| Wisconsin | 5.9 (4.8-7.1) | 1.7 (1.2-2.4) |

| Arizona | 5.7 (4.9-6.6) | 2.5 (1.9-3.1) |

| Washington | 5.6 (5.1-6.2) | 1.9 (1.6-2.3) |

| Alabama | 5.5 (4.7-6.5) | 1.7 (1.3-2.2) |

| Colorado | 5.5 (4.9-6.1) | 1.6 (1.3-1.9) |

| Michigan | 5.4 (4.8-6.1) | 1.1 (0.8-1.3) |

| Florida | 5.3 (4.8-5.9) | 1.9 (1.6-2.2) |

| New Mexico | 5.3 (4.3-6.6) | 1.6 (1.0-2.5) |

| Virginia | 5.3 (4.6-6.0) | 1.6 (1.3-2.0) |

| Missouri | 5.3 (4.4-6.3) | 1.4 (0.9-1.9) |

| Nebraska | 5.2 (4.6-6.0) | 1.5 (1.2-1.9) |

| West Virginia | 5.2 (4.5-6.1) | 2.0 (1.6-2.5) |

| Kansas | 5.2 (4.6-5.8) | 1.8 (1.5-2.1) |

| South Carolina | 5.1 (4.5-5.9) | 2.1 (1.6-2.6) |

| Indiana | 5.0 (4.4-5.8) | 1.8 (1.4-2.2) |

| Georgia | 5.0 (4.2-6.0) | 1.4 (1.0-2.0) |

| Mississippi | 4.9 (4.1-6.0) | 1.1 (0.7-1.6) |

| Oregon | 4.9 (4.1-5.8) | 1.2 (0.9-1.6) |

| Utah | 4.8 (4.3-5.5) | 2.2 (1.8-2.6) |

| Idaho | 4.8 (3.9-6.0) | 1.9 (1.3-2.7) |

| Rhode Island | 4.8 (3.9-6.1) | 1.1 (0.7-1.7) |

| Texas | 4.8 (4.0-5.6) | 1.9 (1.4-2.4) |

| Massachusetts | 4.7 (4.0-5.6) | 1.8 (1.3-2.5) |

| North Carolina | 4.7 (4.0-5.5) | 1.5 (1.1-2.0) |

| Iowa | 4.6 (3.9-5.5) | 1.6 (1.2-2.1) |

| Connecticut | 4.6 (3.9-5.5) | 1.2 (0.8-1.7) |

| Hawaii | 4.6 (3.9-5.4) | 1.8 (1.4-2.4) |

| Pennsylvania | 4.5 (3.9-5.3) | 1.4 (1.0-1.9) |

| Maine | 4.5 (3.8-5.4) | 1.0 (0.7-1.6) |

| Illinois | 4.5 (3.7-5.5) | 1.8 (1.3-2.5) |

| Montana | 4.4 (3.5-5.5) | 1.1 (0.7-1.7) |

| New York | 4.3 (3.9-4.9) | 1.2 (0.9-1.5) |

| Delaware | 4.3 (3.5-5.5) | 1.9 (1.2-2.8) |

| Alaska | 4.1 (3.1-5.5) | 1.3 (0.7-2.4) |

| Minnesota | 4.0 (3.6-4.5) | 1.4 (1.1-1.6) |

| New Jersey | 4.0 (3.2-4.9) | 0.9 (0.6-1.4) |

| Vermont | 3.9 (3.1-5.0) | 1.1 (0.7-1.7) |

| North Dakota | 3.8 (3.1-4.8) | 0.9 (0.6-1.5) |

| Maryland | 3.4 (2.9-3.9) | 1.0 (0.7-1.4) |

| California | 3.3 (2.9-3.8) | 1.0 (0.8-1.4) |

| South Dakota | 3.0 (2.3-4.0) | 0.7 (0.3-1.3) |

| District of Columbia | 2.3 (1.7-3.0) | 0.4 (0.1-0.7) |

| Virgin Islands | 1.7 (0.6-4.7) | 0 (0-0.1) |

| Puerto Rico | 0.7 (0.4-1.2) | 0 (0-0.2) |

Footnotes

Disclosures: Drs. Mirbolouk, Uddin, and Orimoloye report grants from A-TRAC during the conduct of the study. Dr. Benjamin reports grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and American Heart Association, served as associate editor for the journal Circulation, and was a member of the NIH/National Center for Biotechnology Information Observational Study Monitoring Board for the CARDIA (Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults) trial outside the submitted work. Dr. DeFilippis reports grants from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences and NIH during the conduct of the study. Dr. Blaha reports grants from the FDA during the conduct of the study and grants from the NIH, FDA, Amgen Foundation, and Aetna Foundation and personal fees from the FDA, American College of Cardiology, Amgen Foundation, Aetna Foundation, MedImmune, Novartis, Sanofi/Regeneron, and Akcea outside the submitted work. Authors not named here have disclosed no conflicts of interest. Disclosures can also be viewed at www.acponline.org/authors/icmje/ConflictOfInterestForms.do?msNum=M17-3440.

Reproducible Research Statement: Study protocol: Available from Dr. Mirbolouk (hassan.mirbolouk@jhmi.edu). Statistical code: Not available. Data set: Available at www.cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/2016/files/LLCP2016XPT.zip.

Contributor Information

Mohammadhassan Mirbolouk, The American Heart Association Tobacco Regulation and Addiction Center, Dallas, Texas, and Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland.

Paniz Charkhchi, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, and University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Sina Kianoush, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, and Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut.

S.M. Iftekhar Uddin, The American Heart Association Tobacco Regulation and Addiction Center, Dallas, Texas, and Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland.

Olusola A. Orimoloye, The American Heart Association Tobacco Regulation and Addiction Center, Dallas, Texas, and Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland.

Rana Jaber, The American Heart Association Tobacco Regulation and Addiction Center, Dallas, Texas, and Florida International University, Miami, Florida.

Aruni Bhatnagar, The American Heart Association Tobacco Regulation and Addiction Center, Dallas, Texas, and University of Louisville, Louisville, Kentucky.

Emelia J. Benjamin, The American Heart Association Tobacco Regulation and Addiction Center, Dallas, Texas, and Boston University, Boston, Massachusetts.

Michael E. Hall, The American Heart Association Tobacco Regulation and Addiction Center, Dallas, Texas, and University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, Mississippi.

Andrew P. DeFilippis, The American Heart Association Tobacco Regulation and Addiction Center, Dallas, Texas, and University of Louisville, Louisville, Kentucky.

Wasim Maziak, Florida International University, Miami, Florida, and Syrian Center for Tobacco Studies, Aleppo, Syria.

Khurram Nasir, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut, and Florida International University, Miami, Florida and Population Health & Health Systems Research, Center for Outcomes Research and Evaluation (CORE), Section of Cardiovascular Medicine, Yale University School of Medicine.

Michael J. Blaha, The American Heart Association Tobacco Regulation and Addiction Center, Dallas, Texas, and Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland.

References

- 1.Bhatnagar A, Whitsel LP, Ribisl KM, Bullen C, Chaloupka F, Piano MR, et al. ; American Heart Association Advocacy Coordinating Committee, Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, and Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research. Electronic cigarettes: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;130:1418–36. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wackowski OA, Delnevo CD, Steinberg MB. Perspectives for clinicians on regulation of electronic cigarettes. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165:665–6. doi: 10.7326/M16-1345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crowley RA; Health Public Policy Committee of the American College of Physicians. Electronic nicotine delivery systems: executive summary of a policy position paper from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:583–4. doi: 10.7326/M14-2481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Food and Drug Administration; HHS. Deeming tobacco products to be subject to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, as amended by the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act; restrictions on the sale and distribution of tobacco products and required warning statements for tobacco products. Final rule. Fed Regist 2016;81:28973–9106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. E-cigarette use among youth and young adults: a report of the surgeon general. Accessed at https://e-cigarettes.surgeongeneral.gov/documents/2016_sgr_full_report_non-508.pdf on 8 August 2018.

- 6.Murthy VH. E-cigarette use among youth and young adults: a major public health concern. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171:209–10. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.4662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System overview: BRFSS 2016. 2017. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/2016/pdf/overview_2016.pdf on 3 June 2018.

- 8.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Federal poverty line. 2018. Accessed at www.healthcare.gov/glossary/federal-poverty-level-FPL on 8 August 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. LLCP 2016 codebook report, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. 3 August 2017. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/2016/pdf/codebook16_llcp.pdf on 1 January 2017.

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System: weighting BRFSS data. BRFSS 2016. 2017. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/2016/pdf/weighting_the-data_webpage_content.pdf on 3 June 2018.

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, direct age adjustment, 2016. 2017. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/2016/pdf/2016_DirAgeAdjDUsrsGde.pdf on 1 January 2017.

- 12.Kasza KA, Ambrose BK, Conway KP, Borek N, Taylor K, Goniewicz ML, et al. Tobacco-product use by adults and youths in the United States in 2013 and 2014. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:342–53. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1607538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.U.S. Census Bureau. Quick facts: United States. 2017. Accessed at www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045216 on 12 December 2017.

- 14.Muller CJ, MacLehose RF. Estimating predicted probabilities from logistic regression: different methods correspond to different target populations. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43:962–70. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schoenborn CA, Gindi RM. Electronic cigarette use among adults: United States, 2014. NCHS Data Brief. 2015:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coleman BN, Rostron B, Johnson SE, Ambrose BK, Pearson J, Stanton CA, et al. Electronic cigarette use among US adults in the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) study, 2013-2014. Tob Control. 2017;26:e117–26. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jaber RM, Mirbolouk M, DeFilippis AP, Maziak W, Keith R, Payne T, et al. Electronic cigarette use prevalence, associated factors, and pattern by cigarette smoking status in the United States from NHANES (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey) 2013-2014. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.008178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shahab L, Goniewicz ML, Blount BC, Brown J, McNeill A, Alwis KU, et al. Nicotine, carcinogen, and toxin exposure in long-term E-cigarette and nicotine replacement therapy users: a cross-sectional study. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:390–400. doi: 10.7326/M16-1107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glasser AM, Collins L, Pearson JL, Abudayyeh H, Niaura RS, Abrams DB, et al. Overview of electronic nicotine delivery systems: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52:e33–66. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.10.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rigotti NA, Chang Y, Tindle HA, Kalkhoran SM, Levy DE, Regan S, et al. Association of E-cigarette use with smoking cessation among smokers who plan to quit after a hospitalization: a prospective study. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168:613–20. doi: 10.7326/M17-2048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rigotti NA. Balancing the benefits and harms of E-cigarettes: A national academies of science, engineering, and medicine report. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168:666–667. doi: 10.7326/M18-0251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Apelberg BJ, Feirman SP, Salazar E, Corey CG, Ambrose BK, Paredes A, et al. Potential public health effects of reducing nicotine levels in cigarettes in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2018;378: 1725–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1714617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Delnevo CD, Giovenco DP, Steinberg MB, Villanti AC, Pearson JL, Niaura RS, et al. Patterns of electronic cigarette use among adults in the United States. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18:715–9. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu SH, Zhuang YL, Wong S, Cummins SE, Tedeschi GJ. E-cigarette use and associated changes in population smoking cessation: evidence from US current population surveys. BMJ. 2017;358:j3262. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j3262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cobb NK, Abrams DB. E-cigarette or drug-delivery device? Regulating novel nicotine products. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:193–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1105249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kalkhoran S, Glantz SA. E-cigarettes and smoking cessation in real-world and clinical settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Respir Med. 2016;4:116–28. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00521-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]