Abstract

Fats contribute majorly to food flavour, mouthfeel, palatability, texture, and aroma. Though solid fats are used for food formulation due to the processing benefits over oils, their negative health effects should not be overlooked. Oleogelation is thus used to transform liquid oil into a gel which function like fats and provide the nutritional benefits of oils. Additionally, only food-grade gelators convert the oils into solid-like, self-standing, three-dimensional gel networks. Rice bran wax, candelilla wax, carnauba wax, and sunflower wax are mainly used plant waxes for formulating oleogels as a result of their low cost, availability, and excellent gelling ability. A comprehensive information about the wax based oleogels, their characteristics and applications is needed. The present review discusses the effect of different plant-based waxes on the properties of the oleogel formed. The article provides information on how the physical and chemical properties of waxes impact the oleogel properties such as oil binding capacity, critical concentration, rheological, thermal, textural, morphological, and oxidative stability. Moreover, the current and potential applications of oleogels in the food sector have also been covered this article.

Keywords: Solid fats, Fat replacer, Oleogel properties, Microstructure, Oil structuring

Introduction

Fats and oils are important in our diet for a variety of reasons, such as being a source of energy, flavour carriers and solvent for some valuable nutrients and bioactive compounds. Fats provide flavour, mouthfeel, palatability, texture, aroma, functions as leavening agents in batters and doughs, contribute to tenderness, flakiness and emulsification and provides satiety (Pehlivanoğlu et al. 2018). Due to various manufacturing benefits over liquid oils, solid fats are used in various food products. Majorly their plasticity and high melting point offer processing advantages such as extended shelf-life and handling convenience (Jung et al. 2020). For many decades, the negative impact of trans and saturated fats have been debated intensively. The high consumption of such dietary components has been shown to raise the chances of cardiovascular disease (Tanasescu et al. 2004; de Souza et al. 2015). Governments around the world are trying to limit or forbid using trans fats by the means of aggressive laws. For example, the World Health Organization (WHO) advises that saturated fat intake should be lower than 10% of total fat content (Oh et al. 2019). Moreover, the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) instructed to limit trans fatty acids to not more than 3% in all fats and oils by January 2021 and not more than 2% by January 2022. Formulating food products without solid fats is difficult as they provide the products with necessary structure, texture, and mouthfeel (Chung et al. 2013; Blake et al. 2014). At present, different food processes are used to produce shortenings from liquid oils such as interesterification, hydrogenation, and blending of oils (Zhao et al. 2020). Interesterification results in the formation of trans fatty acids which have adverse effects on health (Pehlivanoğlu et al. 2018). Additionally, partially hydrogenated oils have been banned by the FDA in processed foods as they are the major source of artificial trans-fats (Patel and Dewettinck 2016).

It is quite challenging to find alternative methods for the development of fats. The gelation by an organogelator of liquid oil is one of the approaches widely explored in producing a fat-like substance. Oleogelation neither changes the unsaturated fatty acids profile nor does it use chemicals to convert the liquid oil into gel networks (Zhao et al. 2020). It is a useful technique to enhance the nutritional quality of food items, making them high in unsaturated fats, low in saturated fats, and trans-fat free by gelling up to 90 wt% oil (Patel and Dewettinck 2016). Scientists in the food industry have recently shown a strong interest in oleogelation research. The major contributor to this widespread interest is the possibility of replacing shortening in baked goods, animal fat in meat products, cocoa butter in chocolates, and fat in ice cream by oleogels (Botega et al. 2013; Oh et al. 2017, 2019; Li and Liu 2019; Jung et al. 2020).

Oleogels may be made from a diverse range of structural compounds that cause several gelation mechanisms at nano and micro scales, inducing specific macroscopic features (e.g., rheological/textural) (Akterian and Akterian 2022; Puscas et al. 2020). According to studies, natural waxes may gel liquid oils at concentrations as low as 1–4 wt% by creating a three-dimensional network that traps the oil inside of its pores and adsorbs it to the network's surface (Toro-Vazquez et al. 2013). Chemical components of waxes, such as fatty alcohols, fatty acids, and hydrocarbon chains, which depend on their source and relative proportions of these constituents in them, considerably influence their gelation behaviour. The behaviour of gelation is also influenced by the quality of the oil; the better the saturation level, the better the gelation. The benefit of using plant waxes in oleogels is that they are readily available, inexpensive, and of food-grade quality. They can be used to create water-in-oil type structured emulsions that may or may not require emulsifiers, and because of their thermo-reversible behaviour, they can be used successfully for foods that require temperature modulation (Blake et al. 2014; Manzoor et al. 2022). For applications in edible oleogels, plant waxes such as candelilla (CW), carnauba (CRW), rice bran (RBW), and sunflower (SW) waxes are of highest relevance (Hwang et al. 2013; Patel et al. 2014).

When an oil is combined with wax, oleogel with distinct characteristics are produced depending on the type of oil or wax used. The beginning of crystallisation and gelation in compound systems is only controlled by the oil during the gelation process, whereas waxes are responsible for increasing the basic network of oil crystals at low temperatures. However, ultimate elasticity of compound oleogels appears to be more wax-sensitive. A denser crystal network and hydrogen bonding are the key causes of the improved characteristics. Furthermore, different waxes have different spatial distributions, crystal morphologies, and van der Waals interactions, which influence oleogel characteristics differently (Blake et al. 2018; Li et al. 2022). Thus, oleogels with distinctive chemical and physical properties can be created by combining oils with a specific wax for certain food applications. Recently, several outstanding review articles have been published that discusses action of oleogels on overall human metabolic health (Martins et al. 2020), gelation mechanism and development of oleogels using emerging technologies (Manzoor et al. 2022) and applications of oleogels in foods (Puscas et al. 2020). Furthermore, a critical review by Park and Maleky (2020) discussed the last 10 years of research involving oleogels in foods and they also proposed the gaps that are needed to be addressed in future works. One of the major gaps highlighted by them was lack of literature discussing functionl properties of oleogels prepared using food-grade gelators. The most promising plant waxes employed for oleogelation include sunflower wax, carnauba wax, and rice bran wax. These waxes have been used to structure liquid oils and create oleogels, which have a wide range of applications in the food industry. The oleogelation process and oleogels obtained can be characterized by several features, including the type and concentration of wax used, the oil phase, the cooling rate, and the storage conditions. The rheological properties of oleogels, such as gel strength, yield stress, and viscosity, are also important parameters for characterizing the oleogelation process and oleogels obtained. Additionally, the oxidative stability of oleogels is an important factor to consider, as it affects the shelf life and quality of the final product. Therefore, a comprehensive understanding of the properties of plant waxes and the oleogelation process is necessary for the development of new oleogel-based products with improved functionality and stability. Herewith, the review aims to reveal (1) relations between the plant-waxes employed and the physical and functional properties of the oleogels obtained; (2) food applications of these oleogels.

Oleogelators

A structuring agent, called oleogelator, is added to the oil phase to form oleogels (Botega et al. 2013). In general, a three-dimensional network is formed as a result of a self-assembling gelator molecule. The oil phase is stabilized as a result of physical bond formation, like hydrogen and Van der-Waals bonds, as a consequence of which, crystallization, cross-linking, and stacking takes place (Davidovich-pinhas et al. 2015). According to Blake (2015), a good gelator for food applications must be food grade, commercially available, economically feasible, and should gel oil even at low concentrations. The structure of the final oleogel is very much correlated with the characteristics of the gelator, such as shape, number, and size of the crystal and also on physical interactions among building blocks (Calligaris et al. 2020). Different types of oleogelator molecules present are crystalline materials (waxes, fatty acids/alcohols), particle filler (silica particles), macromolecules (polymers like ethyl cellulose, chitin), and others (dried protein/polysaccharide network) (Blake 2015; Davidovich-pinhas et al. 2016).

Molecular weight categorises oleogelators into two types: low molecular weight (molecular weight < 3000) and high molecular weight. Monoglycerides, natural waxes, wax esters, hydroxylated fatty acids, phytosterols, ceramides, lecithin, and oligopeptides are examples of low molecular weight oleogelators while high molecular weight oleogelators include polymers (proteins and polysachharides) such as hydroxypropyl methyl cellulose, alginate, guar gum (Davidovich-pinhas et al. 2015; Patel et al. 2015). A lot of research has also been done on stearic acid and its derivatives in oleogelation, such as 12-hydroxy stearic acid and stearyl alcohol. Polar groups increase interfacial tension between edible oil and the gelators in hydrophobic gels, reducing gel stability. Using stearic acid can increase the stability of anhydrous oleogels. Using polymer gelators to structure oil is relatively new compared to low molecular weight oleogelators. Most proteins and polysaccharides are hydrophilic and cannot be dispersed directly in oil to make oleogels. Thus, indirect methods such emulsion-templated methods have been devised. Proteins and polysaccharides build viscoelastic three-dimensional networks via hydrogen bonding (Davidovich-Pinhas 2019).

Plant based waxes

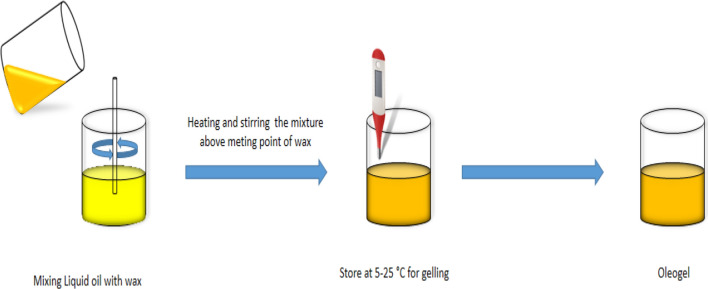

Among various gelator molecules, plant-based waxes have a huge potential due to their higher availability, good structuring properties, and high oil binding capacity coupled with a lower cost (Blake 2015; Zhao et al. 2020). Wax is an ester that is formed by a long-chain alcohol and fatty acid combination and tends to have long hydrocarbon chains, resulting in a reasonably stable structure (Tavernier et al. 2017). Naturally, waxes are present on the plant surface to protect them against water loss and insect attack (Rocha et al. 2013). Plant-based waxes have generated significant levels of excitement over the last decade, as they are highly effective for crystallization at low concentrations and build a matrix with good oil binding characteristics. High melting wax components, long chain length, and low polarity result in good crystallization properties in oil (Doan et al. 2015). For preparing wax-based oleogels (Fig. 1), the wax is dispersed directly into the oil phase at temperatures above their melting points and cooling the mixture to lower temperatures, due to which structuring of oil occurs. Most widely used plant waxes for the formulation of oleogels are RBW, CW, CRW, and SW (Doan et al. 2015; Oh et al. 2017; Hwang et al. 2018; Fayaz et al. 2020; Jung et al. 2020). Some waxes have also been deemed as GRAS by the FDA, including RBW, CW, and CRW under regulations 21 CFR, 172.890, 184.1976, and 184.1978, respectively. The source and chemical composition of various waxes have been shown in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Preparation of oleogel from plant based wax

Table 1.

Sources and chemical composition of natural waxes

| Wax | Source | Melting range | Critical concentration (w/w) | Composition | Content (%) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice bran wax (RBW) | Rice bran | 78–79 °C | 1% | Wax esters | 73.4–93.5 | Dassanayake et al. (2009; Wijarnprecha et al. (2018) |

| Triacylglycerols | 21.9 | |||||

| Free fatty acids | 6 | |||||

| Free aliphatic alcohols | 0.22–4.6 | |||||

| Gum/resinous matter | 0.1 | |||||

| Sunflower wax (SW) | Sunflower seeds | 75–76 °C | 1% | Wax ester | 66–96.2 | Kanya et al. (2007), Doan et al. (2017), Winkler-Moser et al. (2019) |

| Free fatty acids | 3.3–16 | |||||

| Free fatty alcohols | 0.3–10 | |||||

| Hydrocarbons | 0.2 | |||||

| Carnauba wax (CRW) | Leaves of Copernicia prunifera (Miller) H. E. Moore | 79–84 °C | 4% | Wax ester | 38–40 | Hwang et al. (2012), de Freitas et al. (2019) |

| Diesters of 4-hydroxycinnamic acid | 20–23 | |||||

| Free fatty alcohols | 3–12 | |||||

| p-methoxycinnamic aliphatic diesters | 5–7 | |||||

| Lactides | 3 | |||||

| Hydrocarbons | 2 | |||||

| Candelilla wax (CW) | Leaves of Euphorbia cerifera and Euphorbia antisyphilitica | 67–73 °C | 2% | Hydrocarbons | 42–50 | Kuznesof, (2005), Toro-Vazquez et al. (2007) |

| Wax ester | 20–39 | |||||

| Free fatty acids | 7–9 | |||||

| Resins (mainly triterpenoid esters) | 12–14 | |||||

| Lactones | 6 |

RBW is obtained from rice bran. It is majorly produced in East Asia as rice is the main food in that region. Wax is extracted from crude rice bran oil by dewaxing during refining which is achieved by cooling the oil, followed by filtration or centrifugation to separate the wax (Vali et al. 2005; Dassanayake et al. 2009). It mainly consists of long-chain saturated fatty acids (C20–C26) and fatty alcohols (C30–C36) (Wijarnprecha et al. 2018). Moreover, it has high thermal stability (Dassanayake et al. 2012) as it has a high melting point of 78–81 °C, it crystallises easily and results in a fine dispersion when mixed with oil at ambient temperatures (Dassanayake et al. 2009).

CW is derived from the leaves of a small shrub Euphorbia cerifera and Euphorbia antisyphilitica, from the family Euphorbiaceae. It is approved by the US FDA as a food additive and is often used as a glazing agent (Soleimanian et al. 2020) and may also be used in place of beeswax and CRW (Toro-Vazquez et al. 2007). Its melting range is 68–73 °C and majorly consists of odd-numbered saturated straight-chain hydrocarbons from C29 to C33 and even-numbered carbon chain esters from C28 to C34 (Toro-Vazquez et al. 2007).

CRW is retrieved from the leaves of Brazilian palm Copernicia prunifera (Miller) H. E. Moore, found in economically exploited areas in the dry regions of the Northeast caatingas (scrublands) (Freitas et al. 2019). It consists of a complex mixture of aliphatic acids, esters, hydrocarbons (paraffins), ω-hydroxycarboxylic free acids and diols triterpenes, aromatic acids, and free alcohols (Wang et al. 2001). The waxy material prior to extraction from the leaves is called carnauba powder, which is the raw material for producing wax (Freitas et al. 2019). Its melting range is around 65–89 °C which is much higher than other waxes.

SW is mainly located in the sunflower (Helianthus annuus) seeds hull and is extracted with the oil (Öǧütcü and Yilmaz 2015). Crude sunflower oils consist of esters of long‐chain fatty acids and alcohols, having 42–58 carbon atoms which are further refined to increase their market value (Baümler et al. 2014). The composition of the wax fractions as studied by Kanya et al. (2007) was: 66% wax esters, 16% free fatty acids, and 10% free fatty alcohols. The melting point of SW is about 75 °C majorly because of the wax esters present (Winkler-Moser et al. 2019).

Effect of plant-based waxes on oleogel properties

RBW, CW, SW and CRW are majorly used in the formulation of oleogels. Because of the difference in properties of waxes as given in Table 1, the resulting oleogels formed would have different properties such as its critical concentration of gelling, oil binding capacity, firmness, stickiness of the oleogel, and melting point, etc. (Pehlivanoğlu et al. 2018; Fayaz et al. 2020) which are discussed in this section.

Critical concentration (C*)

Blake (2015) defines critical concentration as the least amount of wax required for gelling oil which is determined as follows. An increasing concentration of oleogelator is dissolved in oil at high temperatures to form solutions. The concentration increment generally used is 1%. The solution is then cooled overnight to allow gel formation. Thereafter, the sample tubes or vials are inverted and critical concentration is determined visually. It is the lowest concentration which results in a sample that does not flow while the tube is inverted (Hwang et al. 2012; Blake 2015). The C* as reported by Blake (2015) for both RBW and SW was 1% (w/w), 2% (w/w) for CW, and 4% (w/w) for CRW in canola oil. These results are similar to the study done by Hwang et al. (2012), where the gelling ability of different waxes in soybean oil was evaluated. The mixture of p-hydroxycinnamic aliphatic diesters and aliphatic esters present in CRW results in its poor gelling since it is not as effective as wax esters. Doan et al. (2015) also evaluated the gelling characteristics of waxes in rice bran oil and found similar results. At 5 °C they reported the minimum concentration required as 1.0–1.5% for CW and SW. Though they concluded that below 5%, RBW could not form a gel with rice bran oil. This variation was due to the higher solubility of RBW in rice bran oil, thus, increasing the minimum gelling concentration.

The value of C* depends on various factors of the gelator molecule. Hwang et al. (2012) stated that good gelling abilities were evident with (a) wax esters than with p-hydroxycinnamic aliphatic di-ester, (b) saturated alkyl chains of esters, (c) longer alkyl chains of wax esters, and (d) wax esters than with triacylglycerols. Patel et al. (2015) also agree that gelation occurs later for waxes composed of high- and mid-melting components. Moreover, the higher solubility of components further increases C* value. Thus, the chemical composition (Table 1) of the wax is significant in determining the C* of the gelator. From these studies, it can be inferred that, among the discussed oleogelators, SW has the minimum critical concentration required to form a gel.

Oil binding capacity

Oil binding capacity (OBC) is a critical property of oleogels as it indicates the extent of entrapment of oil in the gel network by the organogelator (Pandolsook and Kupongsak 2017). Various studies employ centrifugation for the determination of OBC (Pandolsook and Kupongsak 2017; Canizares et al. 2019; Thakur et al. 2022). Previously weighed Eppendorf tubes (a) are filled with 1–2 mL of melted oleogel sample, which is then cooled in refrigerator for gelation. Then the tubes are weighed again (b) and centrifuged for around 15 min at around 9000 g and inverted to drain excess oil. The drained weight of tube (c) is noted and OBC is calculated as given below.

Various researches have been carried out to determine the OBC of oleogels prepared using plant waxes. Gur et al. (2017) concluded from their study that among various waxes, CRW oleogel had an OBC of 53.17% with the highest value of k (2.19), showing higher loss of oil, which shows that it has poor stability. On the other hand, RBW and CW had an OBC of 99.11% and 100% respectively. This high OBC of RBW is contradictory since Fayaz et al. (2020) reported it to be 81% while Blake et al. (2014) reported it to be even lower than that of CRW. This might be due to the fact that in the earlier mentioned study, the concentration of oleogelator molecule was taken to be 3% (which is below the C* of CRW and much higher than that of RBW) whereas the latter studies were done at the minimum gelling concentration, i.e. C*. In another study, Öǧütcü and Yilmaz (2015) observed that the OBC of the CRW oleogels at a concentration of 3% was much lower than SW oleogels. This is because CRW has a higher C* value (4%) as discussed in the previous section. At 7% the OBC of both CRW and SW was 80.6% and 99.8% respectively, which is a significant difference. Fayaz et al. (2020) also reported the OBC of SW to be greater than 99%. This also indicates that wax concentration is directly related to OBC (Canizares et al. 2019).

The high OBC is attributed to the small size of wax particles (smaller void spaces making it difficult for oil to leach out) and also the uniform distribution of particles in the material (Blake et al. 2014). Another interesting factor that affects the OBC is the cooling rate during crystallization of oleogel as reported by Blake (2015). Thus the decreasing order of OBC of various waxes may be concluded as CW ≥ SW > RBW > CRW.

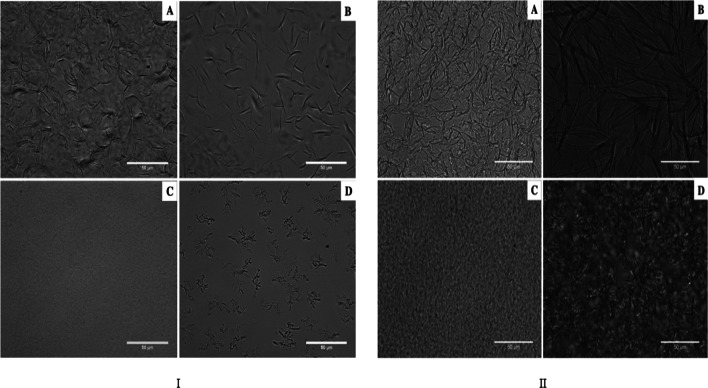

Morphology

The solid phase microstructural arrangement and the way it interacts with the liquid phase affect much of its texture and rheology in food systems. This is observed in systems where TAG (Triacylglycerol) crystallization has a significant role, i.e., butter, chocolate, margarine (Toro-Vazquez et al. 2007). As per the study done earlier by Dassanayake et al. (2009), it was believed that the spherulitic structures of CRW and CW would be unable to form organogels. Whereas, the long needle-like crystals, as that of RBW were necessary for the formation of the entangled network required for binding oil. Blake et al. (2014) also reported the structure of RBW crystals to be needle like with a length of 10–20 µm, whereas CRW, CW, and SW had dendritic (10–20 µm), grain-like (3–5 µm), and fibrous crystals (15–25 µm), respectively as shown in Fig. 2. They also observed that the crystal size increased with wax concentration. Recent studies (Blake 2015; Winkler-Moser et al. 2019) reported that wax crystals from RBW, SW, and CW have a morphological association to mineral waxes, as they have a platelet-like morphlogy as shown in Fig. 3. CW oleogel had a uniform dispersion of randomly oriented platelets having 5 μm length and SW oleogels had large (30–50 μm) platelets. This structural difference was attributed to the crystallization on a glass substrate while preparing the sample. Due to their high ester content, waxes are hydrophobic and crystallization on glass is not favourable thermodynamically as it is hydrophilic. Therefore, by crystallizing on the edge of the platelet, the area of contact between the hydrophilic glass and hydrophobic wax is reduced (Blake 2015). Hence, traditional optical microscopy techniques do not comprehensively depict the crystal morphology of wax. Thus, techniques like phase contrast light microscopy or cryogenic scanning electron microscopy (cryo-SEM) are necessary for studying their morphology. Since the crystal morphology was the same, Blake (2015) suggested that the surface area (or platelet size) should be taken into account while discussing wax morphology and oil structuring ability. In accordance with this finding, Tavernier et al. (2017) carried out Cryo-SEM imaging of waxes in rice bran oil and concluded that higher surface area of wax results in better oil binding and gelation capacity of SW over RBW.

Fig. 2.

Brightfield light micrographs of wax organogels consisting of canola oil and rice bran wax (a), sunflower wax (b), candelilla wax (c) and carnauba wax (d) at (I) their respective critical concentrations and (II) relatively high concentrations of 10% w/w

(Source: Blake 2015)

Fig. 3.

Cryo-SEM micrographs at high magnification (left column) and low magnification (right column) of wax oleogels containing 2% RBW (top row), 2% SW (middle row) and 2% CW (bottom row) in peanut oil

(Source: Blake 2015)

Hardness

The textural characteristics are as significant as thermal properties, since adhesion, spreadability, and oil separation phenomena of plastic fats can be defined by it (Öǧütcü and Yilmaz 2015). For industrial applications, the hardness of organogel is a critical factor. The hardness of oleogels is measured using texture profile analyzer by using different probes such as conic acrylic probe (Öǧütcü and Yilmaz 2015), round compression probe (Pandolsook and Kupongsak 2017; Hwang et al. 2018), and ball probe (Zhao et al. 2020). Irrespective of the probe, the hardness of the oleogel is given by the maximum force recorded during the TPA cycle. Neither hard nor soft states are favourable for the good quality of organogels (Dassanayake et al. 2012). Generally, studies in which oleogel has been used as a fat (shortening) replacer have reported the firmness of oleogel to be higher as compared to shortening (Jang et al. 2015; Oh et al. 2017; Jung et al. 2020). The compact and dense cell structure of the oleogel due to its low specific volume can primarily explain this result (Oh et al. 2017). While comparing the hardness of olive oil oleogels made with RBW, CW, and CRW, Dassanayake et al. (2009) found that RBW oleogel had the highest hardness in terms of least penetration depth (6 mm) than CW (8 mm) and CRW (13 mm) at 6% concentration of wax, which was attributed to the crystal morphology. The fiber-like, needle crystals of RBW result in a stronger gel network which forms a harder gel. In a similar study done by Öǧütcü and Yilmaz (2015), no significant difference in the firmness of CRW and SW was observed. While Gur et al. (2017) reported that high-oleic sunflower oil oleogels made with CW (3%) had higher hardness than RBW (3%). Whereas, at the critical concentration of oleogelators, it was reported that the hardness is a result of the interaction between different micro-structural factors such as solids volume fraction, fractal dimension, and particle size. From the parameters mentioned (solids volume fraction, fractal dimension, and particle size), the major contributor to hardness is the particle size. Hence, the smaller particle size of CW, makes it harder than RBW and SW (Blake et al. 2014). Hence the decreasing order of hardness was reported as CRW > CW > RBW > SW.

Gel firmness increases considerably as the cooling rate increases due to the formation of a higher number of smaller crystals. As observed by Hwang et al. (2012), many small crystals were produced at a fast cooling rate (10 °C/min) whereas fewer and larger crystals were obtained at lower cooling rates (1–5 °C/min). It was also determined that gels formed at a higher cooling rate were significantly firmer than those formed at lower cooling rate. Small crystals resulted in a dense network which resists deformation as compared to a network of larger crystals. Apart from this, as the concentration of wax is increased, an increase in the firmness of oleogel is observed. Oleogel at 10% concentration of wax were firmer than at 7% which in turn had a higher firmness than 3% wax concentration for both CRW and SW oleogels (Öǧütcü and Yilmaz 2015). Thus, textural properties of the oleogel can be easily controlled by adjusting the concentration, cooling rate, and the type of oil in which the wax is to be incorporated.

Melting behaviour/thermal properties

Since the oleogels are majorly used as a fat/shortening replacer in the food industry, thus it is essential to study their melting profiles which must resemble that of fat so as to properly mimic its sensorial attributes. Single-peaked thermographs were observed for RBW and SW while CW and CRW showed multi-peak profiles (Rocha et al. 2013; Blake 2015; Patel et al. 2015). RBW and SW are composed of a single chemical class of wax esters, due to which single crystallization and melting peaks are obtained. Whereas, CRW and CW have multiple chemical classes due to which complex crystallization and melting behaviour are observed (Dassanayake et al. 2009). Doan et al. (2015) found that at the same concentration, SW oleogel had the least ∆T value (4.67 °C), followed by CW (12.43 °C), CRW (16.20 °C) and RBW (19.51 °C). The lower ∆T (difference in temperature) indicates easier gel formation. The organogels’ melting parameters, particularly ΔHM (heat of melting), was related to the structural order of the gelator molecules. Developing organogels at a high cooling rate resulted in a low degree of molecular organization (i.e., lower ΔHM) as compared to organogels developed at a lower cooling rate. The peak crystallization temperature, peak melting temperature, enthalpy of crystallization (ΔHc), and enthalpy of melting (ΔHm) increased with increasing concentration of wax (Blake 2015). Thus the thermal properties of the oleogel are dependent on the amount of wax used in the formulation. Wijarnprecha et al. (2018) also studied the thermal behaviour of RBW oleogels at different concentrations (0.5–25%). The Ton and Tp increased from 50 and 47 °C at 0.5% RBW to 73 and 71 °C in the gel with 25% RBW. Similarly, the melting temperature at 0.5% RBW (59 °C) was lower compared to 25% RBW (75 °C). Yi et al. (2017) reported that with an increase in wax concentration in oleogels, enthalpy and temperatures of crystallization and melting increased.

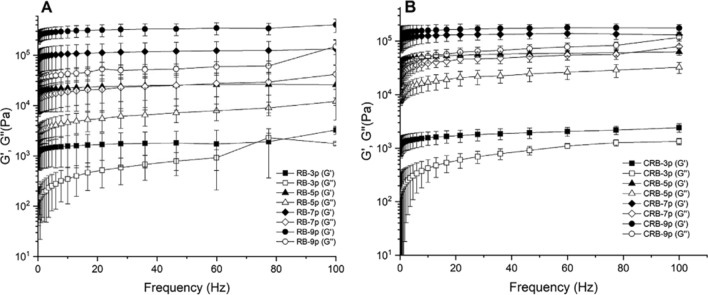

Rheological properties

The rheological properties of oleogels influence the quality of products in which they are incorporated. Oil type, concentration, and oleogelator type are some of the important factors which impact the rheological properties of oleogels. The storage modulus (G′) and loss modulus (G″) versus strain percentage plot gives the linear viscoelastic region (LVR) in amplitude sweep test, which gives information about material stability. At small applied shear, the elastic component (G′) of gels dominates the viscous component (G″) and reaches a plateau (G′LVR) in the LVR (flat part at the beginning of the amplitude sweep curve). The first point where G′ varies by 10% of G′LVR marks end of LVR and the corresponding stress at this point is the critical stress. With further increase in the applied shear, a permanent deformation (yielding) of the materials may occur (G′ = G″) and the corresponding stress value at this point is known as dynamic or oscillatory yield stress (Patel et al. 2015; Thakur et al. 2022). According to the gelation techniques, waxes have been the most effective oleogelator as reported by several authors, because of their ability to build well-formed network having strong oil binding capacity, polymer gelation, and self-assembled fibrillar network (Toro-Vazquez et al. 2007; Dassanayake et al. 2009; Blake and Marangoni 2015; Doan et al. 2015).

Patel et al. (2015) carried out the rheological profiling of oleogels at critical gelling concentrations of natural waxes. They observed that among the different oleogels (SW, CRW, CW, beeswax, berry wax and fruit wax), CRW gels had a higher G′LVR value, and higher oscillatory yield stress in comparison to other gels. Moreover, SW gel was softer than CRW and yielded at much lower force (9.9 Pa compared to 19.8 Pa for CRW gel). Recently, Zhao et al. (2020) discussed the rheological properties of RBW oleogels at different concentrations (3, 5, 7, and 9 wt%) with either refined corn oil (RCO) or expeller-pressed corn germ oil (EPCGO) (Fig. 4). Frequency sweep tests showed G′ > G″ at all RBW concentrations exhibiting solid-like property, thereby indicating the good tolerance to deformation of oleogels. Further, an increased G′ and G″ was noticed with increasing RBW concentrations. Oleogels prepared with 9 wt% RBW showed G′ and G″ 100 times greater than oleogles with 3 wt% RBW. It shows that oleogels prepared with lower wax concentrations have a lower tolerance to deformation. As mentioned earlier, oil type also influences the rheological properties of oleogels. RCO oleogel exhibited higher G′ and G″ than EPCGO oleogels at the same RBW concentration. This indicates that RCO formed a stronger gel than EPCGO. The difference in rheological properties upon varying oil type, maybe due to the removal of minor constituents (phospholipids, metal ions, and free fatty acids) during the refining process in RCO.

Fig. 4.

Frequency dependence of elastic modulus (G′) and viscous modulus (G″) for A refined corn oil oleogels; B expeller-pressed corn germ oil oleogels made with rice bran wax at various concentrations (3, 5, 7, and 9 wt%) at 25 °C

(Source: Zhao et al. 2020)

In another study, Oh et al. (2017) reported the rheological properties of cakes prepared using oleogels from natural waxes (RBW, Beeswax, and CW) added at 10% by weight to sunflower oil. Replacing shortening with oleogels showed a reduction in viscosity, which may be due to the relatively low solid fat content of oleogels than shortening (Lim et al. 2017a, b). Further, values of flow behaviour (n) of cake added with oleogels prepared using RBW (0.61) and CW (0.60) were higher than the control cake (0.55), indicating less degree of shear-thinning characteristics. The consistency index (K) of cake decreased after the addition of oleogels prepared using RBW (7.96), and CW (7.38) as compared to control (24.18). Viscoelastic parameters (G′ and G″) of cake batters lowered after addition of oleogels. Therefore, wax oleogels may replace fat in bakery products without significantly affecting their original characteristics and thus offer a wide range of products to the consumers.

Oxidative stability

For manufacturing certain bakery products, solid-like lipids are favoured due to their greater oxidative stability and solid lipid functionality. The storage stability of products is reduced by using vegetable oil mainly due to oil oxidation which adversely influences the oil's quality and shelf life (Oh et al. 2019; Pehlivanoğlu et al. 2018). Hence, the oxidative stability is an important parameter which is generally assessed by measuring the peroxide value (PV) and is the indicator of primary lipid oxidation of the samples (Park et al. 2018). The PV of edible vegetable oils should not exceed 10–15 meq/kg of oil as per the CODEX Alimentarius Commission (Lim et al. 2017a, b).

Hwang et al. (2018) analysed the oxidative stability of fish oil oleogels made of natural waxes (RBW, SW, CW, and beeswax) at 35 °C, 50 °C, and 90 °C and compared them with bulk oil. At 35 °C on Day 7, PV’s were lower than control in all 3% oleogel samples, which shows that oil oxidation decreased by the gelling of oils regardless of the type of wax. For better understanding, the wax based fish oils were kept at 35 °C for 59 days and the conjugated diene value (CDV) was measured. It was concluded that at 35 °C, CW was the most effective, followed by SW and RBW. However, at 50 °C RBW proved to be the best and the oxidative stability decreased drastically. The wax crystal networks of SW and CW were compromised at 50 °C, owing to their low melting point, whereas RBW had a relatively low CDV and the lowest PV at 50 °C due to its high melting point. Thus, oleogels must be stored at the lowest possible storage temperature in order to attain maximum shelf life and oxidative stability.

Öǧütcü and Yilmaz (2015) gelled hazelnut oil with SW and CRW and monitored their oxidative stability for 90 days at 4 °C and 20 °C, respectively. The oxidative stability of SW oleogel during storage for three months was better than that of CRW oleogel, which clearly indicates the better stability of SW oleogel. Bemer (2018) reported that oleogels made with high-oleic soybean oil (HOSO) and RBW experienced greater lipid oxidation than fresh HOSO which was attributed to the oleogel being heated to 85 °C during processing. Yi et al. (2017) also analysed the oxidative stability of CRW oleogel and concluded that the oleogel was more stable compared to the control oil. On analysing the headspace volatile components, it was clear that with the increasing proportion of carnauba wax the amount of volatile compounds decreased which shows that the concentration of wax and oxidative stability of oleogel have a direct relationship. Another interesting observation was that increasing the cooling rate reduced the oxidation of oleogel (Hwang et al. 2018). SW-fish oil oleogels prepared at faster cooling rates (11.0 °C/min and 25.3 °C/min), had lower PV and CDV than the oleogel prepared at the slower cooling rate (5.3 °C/min). The increasing stability due to the use of oleogels is believed to be due to the comparatively slow circulation of oil in oleogel which results in slower oxidation (Hwang et al. 2018; Oh et al. 2019).

Applications of oleogels in food

The ability to structure oil provides oleogels with various applications for food. In recent years, the data published on wax-based oleogels have increased enormously. A number of products high in either saturated or trans fats have been examined for the application of oleogels. The use of oleogels in industrial as well as scientific fields has grown because of their promising characteristics. Due to their high saturated (50–60%) and trans-fatty acids (14–19%) content, shortenings pose a threat to human health (Table 2). The major role of oleogels is to reduce the amount of saturated fatty acids because excessively consuming them poses various health problems like cardiovascular disease, diabetes, obesity, and metabolic syndrome (Pehlivanoğlu et al. 2018; Flöter et al. 2021). In the food segment industrial research of oleogels is majorly seen in three principal categories: 34% bakery, 24% meat products, and 22% spreads, and other uses make up 20% of the whole research (Soleimanian et al. 2020). Various applications of oleogels in the food industry are given in Table 3. Some of the oleogel based products compared to control are also given in Fig. 5.

Table 2.

Properties of commercial shortening versus oleogel

| Sample | Saturated fatty acids (%) | Unsaturated fatty acids (%) | Trans fatty acids (%) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Margarine | 50–60 | 35–50 | 14.0–19% | Mert and Demirkesen (2016a, 2016b), da Silva et al. (2018) |

| 2.5% CRW in sunflower oil | 14–16 | 85.8 | – | Mert and Demirkesen (2016a) |

| 3% CW in canola oil | 11.1 | 88.9 | – | Mert and Demirkesen (2016b) |

| 2.6% CW in high-oleic sunflower oil | 12.94 | 66.89 | 0.09 | da Silva et al. (2018) |

| 3% CRW in hazelnut oil | 2.7 | – | – | Öǧütcü and Yilmaz (2015) |

| 10% beeswax in sunflower oil | 16.8 ± 0.8 | 83.2 ± 1.1 | – | Demirkesen and Mert (2019) |

Table 3.

Oleogel applications in food

| Application | Product | Wax used | Oil | Wax concentration | Shortening/fat replaced | Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alternative for baking fat | Sweet pan bread | Candelilla wax | Rice bran oil | 10% | 25, 50, 75, 100% |

Upto 75% replacement, bread had similar specific volume and hardness to control SFC reduced from 71.0 to 25.3 g/100 g |

Jung et al. (2020) |

| Cake |

Rice bran wax Beeswax Candelilla Wax |

Sunflower Oil | 10% | 100% |

Replacement by oleogels reduced the total porosity while no significant difference was observed in the specific volume between the control and beeswax cakes Saturated fatty acids in the cakes containing oleogels were significantly reduced to 14–17%, compared to the control with shortening (58%) |

Oh et al. (2017) | |

| Cookie | Candelilla wax | Canola oil | 3 and 6% | 30 and 60% |

Oleogel/shortening blends resulted in higher hardness values than oleogels and it provided similar textural properties that were marginally softer than shortening containing dough 60% replacement with 6% oleogel provided similar hardness to control sample Lower extensibility values were obtained with higher amount of oleogels and shortenings in dough samples |

Mert and Demirkesen (2016b) | |

| Cookie | Rice bran wax | Corn germ oil | 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9% | 100% |

No significant difference in color values, weight, thickness, and spread ratio of cookies was observed As the concentration of RBW increased from 3 to 9%, the hardness of the oleogel increased from 0.17 to 4.44 N; but the hardness of cookies reduced from 114.93 to 76.08 N which shows a inverse relationship |

(Zhao et al. 2020) | |

| Milk fat alternative | Ice cream | Rice bran wax | High-oleic sunflower oil | 10% | 100% |

RBW ice cream had higher levels of overrun compared to HOSO The mean equivalent diameter of oleogel ice cream (10.61 µm) was comparable to that of milk fat control (8.95 µm) |

Botega et al. (2013) |

| Cream cheese | Rice bran wax | High-oleic Sunflower oil | 10% | 100% |

25% reduction in total fat content in comparison to the full-fat commercial control Oleogel cream cheese samples prepared with RBW displayed comparable hardness, spreadability, and stickiness values to the full-fat commercial control sample |

Bemer et al. (2016) | |

| Cocoa butter alternative | Chocolate spread |

Beeswax Propolis wax |

Pomegranate seed oil | 5% | Mixed with palm oil (1:1) |

Chocolate spread made of both BW and PW had a significantly higher G′ than G″ The OBC of wax based chocolates were also high since the released oil lower than 6% for all the samples |

Fayaz et al. (2017) |

| Meat fat alternative | Pork liver pâtés | Beeswax | Olive, linseed, and fish oil mixture | 11% | Pork backfat was replaced partially (50%) ad 100% |

No differences (p > 0.05) in moisture, protein, fat, and ash contents were found among the pâtés Replacing the pork backfat with oleogel produced significant changes in the fatty acid profile As the proportion of animal fat replacement by oleogel increased, the SFA content decreased (p ≤ 0.05) and PUFA increased (p ≤ 0.05), while MUFA experienced fewer quantity variations Color as well as the penetration force were scarcely affected The sensory scores (9 point hedonic scale) although were lower (~ 6) than control (~ 7), but no objectionable attributes were present |

Gómez-Estaca et al. (2019) |

| Fermented sausages | Beeswax | Linseed oil | 8% | 20 and 40% |

Fatty acid profile improved in terms of nutrition: the polyunsaturated fatty acid/saturated fatty acid (PUFA/SFA) and n-6/n-3 ratio was 0.93 for 40% BW oleogel Increasing the amount of BW oleogel in the formulation, increased the L value of the sausages The L value at 40% (54.68) was comparativley higher than at 20% (46) and control (44) which may affect the consumer acceptability |

Franco et al. (2020) | |

| Breakfast spreads | Margarine | Candelilla wax | High-oleic sunflower oil | 2.66% | – |

Visually, the oleogel margarine (OM) was similar to commercial margarine (CM) L* values for OM and CM ranged between 79 and 89 The spreadability of CM (4.80) was lower than that of OM (5.48). Thus the OM was more spreadable than CM The OM samples presented higher melting temperature than CM due to a higher melting point of the wax in relation to TAG with saturated or trans fatty acids Although initially the peroxide values of CM (0.3) were much lower than OM (1.1), with increasing storage time (180 days), the PV of CM (2.1) and OM (2.6) were almost similar A 44% reduction in saturated fatty acids and a 92% reduction in trans fatty acids, compared with commercial margarine was also observed |

da Silva et al. (2018) |

| Margarine |

Sunflower wax Carnauba wax |

Hazelnut oil | 3, 7 and 10% | – |

The peak melting temperature of commercial shortening, SW oleogel, and CRW oleogel were 52.3 °C, 58.4 °C and 81.04 °C respectively The firmness and stickiness values of oleogel samples were lower than that of commercial shortening There was no significant change of firmness and stickiness during storage, indicating good stability (p ≤ 0.001) Furthermore, the oleogels were very stable against oxidation during the storage period The highest PV (0.6 meqgO2/kg) was measured in 3% CW containing oleogel stored at 20 °C for 90 days. At the same temperature, the PV for CS reached its max value of 0.5 meqgO2/kg after 90 days |

Öǧütcü and Yilmaz (2015) | |

| Deep-fat frying medium | Fried Noodles | Carnauba wax |

Soybean oil = |

5 and 10% | Used as a frying medium |

Using oleogels as a deep-fat frying medium significantly decreased the oil uptake of the noodles by about 16% compared to the palm oil-fried noodles Greater breaking strength was observed in the oleogel noodles (> 6) as opposed to palm (5.9) and soybean oil-fried noodles (5.7) The palm oil-fried noodles contained the highest level of saturated fatty acids (54 g/100 g) and the lowest level of unsaturated fatty acids (46 g/100 g) On the other hand, the noodle samples fried in oleogels were low in saturated fatty acids (19 g/100 g) and high in unsaturated fatty acids (81 g/100 g) The highest peroxide values were observed in the noodles fried in soybean oil, followed by 5 g/100 g oleogel, 10 g/100 g oleogel, and palm oil |

Lim et al. (2017a, b) |

| Fried chicken | Carnauba wax | Canola oil | 5 and 10% | Frying medium |

Oleogel-fried samples had significantly lower fat contents than canola oil-fried samples No improve in oxidative stability was observed The protein and ash content of the fried chicken were not significantly different The chicken fried in oleogels had a higher L* value than samples fried in oil. The L* of fried samples in 5 and 10% oleogels was 57.4 and 55 respectively. Whereas the L* of oil fried samples was 45.5 Oleogel fried chicken samples had a lighter appearance No significant difference in the puncture force of different samples was observed |

(Adrah et al. 2022) |

Fig. 5.

Visual appearance of Oleogel Products versus Margarine Products (Yilmaz and Öğütcü, 2015; Oh et al. 2017; da Silva et al. 2018)

The oleogelation approach has the potential to cater to a number of applications for the food industry specifically. These applications broadly include: (a) reducing saturated fat content, (b) reducing trans fatty acid content (c) stabilization of surfactant-free emulsions, (d) decreasing the oil uptake in fried foods, (e) decreasing oil mobility and migration in chocolate products (controlling fat bloom in filled chocolates), (f) improving temperature stability in certain food products (heat-resistant chocolates), and (g) transforming liquid oils into a new range of edible materials, such as foams, films and soft pliable solids (Patel 2017). Oleogels have been a successful replacement for bakery shortening in products such as cake, cookie, and bread. The textural properties of oleogel products were reported to be similar to control. Moreover, a marked reduction (~ 60%) in the saturated fat content has also been observed. A novel application of using oleogels as a frying medium was also reported (Lim et al. 2017a, b; Adrah et al. 2022). Using oleogels in place of oil showed a consequent decrease in the oil uptake of fried samples along with better visual characteristics of the product. The ability to transport lipophilic substances is one of the key benefits of oleogels, which finds another application in the food industry. β-carotene was used to tailor beeswax based oleogels which resulted in better OBC and strength (Martins et al. 2017). Oleogels can also be supplemented with volatile aroma compounds as shown in the study by Yilmaz et al. (2015). Vitamin (E and D3) enriched and aromatized hazelnut oil-sunflower wax oleogel was prepared which did not impact the physical, structural and thermal properties. Even after storage of 3 months, the aromatic compounds were intact. Asumadu-Mensah et al. (2013) investigated the potential of candelilla and carnauba wax dispersions as a delivery system for functional ingredients. The delivery system was thermally stable for a period of 3 months. The particle size and particle size distribution of the samples remained the same after the heating and cooling process. Rosmarinic acid—a polyphenol with bioactivities, such as antioxidant, anti-mutagenic, anti-bacterial and anti-viral capabilities, was encapsulated using carnauba wax as lipidic matrix (Madureira et al. 2015). Throughout the 28 day of refrigerated storage, the structure and stability were intact and no rosmarinic acid was released during refrigeration, indicating good compatibility between rosmarinic acid and the waxy core. Therefore, oleogels can also be used to deliver functional compounds through food matrices.

Challenges in using oleogels for food product preparation

Though the results of using oleogels in various foods are promising, researchers have faced some challenges in mimicking the textural properties of the control sample in their studies. Although there are certain oleogel matrices that mimic the textural properties of control sample (Jung et al. 2020), the optimal combination which also doesn’t affect the sensory properties, remains a big challenge. The off-flavors and odors that oleogel foods may generate are also a major hurdle restricting their use. Bemer et al. (2016) highlighted the off-flavor and bitterness detected by sensory panelists from the RBW oleogel cream cheese products. Thus, there is certainly a need for sensory studies as highlighted above. The higher cost of structured oils compared to palm oil is another major challenge. Moreover, the ability to predict the success of the gelation process in the presence of other ingredients and contamination in food systems, understanding of the metabolic processes and the overall impact of oleogels on human digestion, as well as the imprecise control of process variables (such as temperature and pH), are additional challenges (although they are not the only ones).

Future trends and conclusion

Despite being in its infancy, the field of oil structuring has generated huge interest from academia and industry. This is supported by an increasing number of articles and conferences related to this field. Natural waxes closely resemble all the desired characteristics among the food-grade gelators. The various applications of oleogel technology in food highlight their unlimited potential as an alternative to saturated fat in food products. This helps in making products that are high in unsaturated fats, thereby providing health benefits and reducing the risk of diseases caused due to the consumption of saturated fats.

Despite promising results, products containing oleogel are not available commercially. Like most of the novel designed food systems, certain issues need to be addressed to achieve industrial applications of oleogels. Not all oleogelators are approved to be used as direct additives in food products to form an oleogel, hence regulatory changes are required. Data pertaining to the sensory studies of oleogel based products is limited. These help in evaluating the sensory characteristics of the oleogel-including products. Therefore, sensory studies must be carried out which would further help in enhancing their industrial applicability in the future. The field of oleogelation is progressing quickly and if this trend continues, detailed studies in real food systems will surely be seen in the near future. Moreover, the policy changes which call for eliminating trans fats and the shortcomings of consuming saturated fats, together with increasing consumer awareness would certainly increase the research related to fat reformulation.

Abbreviations

- RBW

Rice bran wax

- CW

Candelilla wax

- CRW

Carnauba wax

- SW

Sunflower wax

- WHO

World Health Organization

- USFDA

United State Food and Drug Administration

- FSSAI

Food Safety and Standards Authority of India

- C*

Critical concentration

- OBC

Oil binding capacity

- TAG

Triacylglycerol

- LVR

Linear viscoelastic region

- RCO

Refined corn oil

- EPCGO

Expeller-pressed corn germ oil

- PV

Peroxide value

- CDV

Conjugated diene value

- HOSO

High-oleic soybean oil

Author contributions

All authors have contributed equally.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Data availability

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The author and co-authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Adrah K, Adegoke SC, Tahergorabi R. Physicochemical and microbial quality of coated raw and oleogel-fried chicken. LWT. 2022;154(October 2021):112589. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2021.112589. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Akterian S, Akterian E. Oleogels–types, properties and their food, and other applications. Food Sci Appl Biotechnol. 2022;5:1–11. doi: 10.30721/fsab2022.v5.i1.156. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baümler ER, Carelli AA, Martini S. Preparation and physical properties of calcium pectinate films modified with sunflower wax. Eur J Lipid Sci Technol. 2014;116(11):1534–1545. doi: 10.1002/ejlt.201400117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bemer HL. Analysis of oil stability in oleogel cream cheese product. J Chem Inf Model. 2018;53(9):1689–1699. [Google Scholar]

- Bemer HL, Limbaugh M, Cramer ED, Harper WJ, Maleky F. Vegetable organogels incorporation in cream cheese products. Food Res Int. 2016;85:67–75. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2016.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake AIE. The microstructure and physical properties of plant-based waxes andtheir relationship to the oil binding capacity of wax oleogels (Master's thesis) Canada: University of Guelph; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Blake AI, Marangoni AG. The use of cooling rate to engineer the microstructure and oil binding capacity of wax crystal networks. Food Biophys. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s11483-015-9409-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blake AI, Co ED, Marangoni AG. Structure and physical properties of plant wax crystal networks and their relationship to oil binding capacity. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 2014;91(6):885–903. doi: 10.1007/s11746-014-2435-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blake A, Toro-Vazquez J, Hwang H-S. Wax oleogels. In: Marangoni A, Garti N, editors. Edible oleogels structure and health implications. 2. Urbana: AOCS Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Botega DCZ, Marangoni AG, Smith AK, Goff HD. The potential application of rice bran wax oleogel to replace solid fat and enhance unsaturated fat content in ice cream. J Food Sci. 2013;78(9):1334–1339. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.12175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calligaris S, Alongi M, Lucci P, Anese M. Effect of different oleogelators on lipolysis and curcuminoid bioaccessibility upon in vitro digestion of sunflower oil oleogels. Food Chem. 2020;314:126146. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.126146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canizares D, Angers P, Ratti C. A proposal standard methodology for the characterization of edible oil organogelation with waxes. Grasas y Aceites. 2019 doi: 10.3989/GYA.0106191. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chung C, Degner B, Decker EA, McClements DJ. Oil-filled hydrogel particles for reduced-fat food applications: fabrication, characterization, and properties. Innov Food Sci Emerg Technol. 2013;20:324–334. doi: 10.1016/j.ifset.2013.08.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva TLT, Chaves KF, Fernandes GD, Rodrigues JB, Bolini HMA, Arellano DB. Sensory and technological evaluation of margarines with reduced saturated fatty acid contents using oleogel technology. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 2018;95(6):673–685. doi: 10.1002/aocs.12074. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dassanayake LSK, Kodali DR, Ueno S, Sato K. Physical properties of rice bran wax in bulk and organogels. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 2009;86(12):1163–1173. doi: 10.1007/s11746-009-1464-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dassanayake LSK, Kodali DR, Ueno S, Sato K. Crystallization kinetics of organogels prepared by rice bran wax and vegetable oils. J Oleo Sci. 2012;61(1):1–9. doi: 10.5650/jos.61.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidovich-pinhas M, Barbut S, Marangoni AG. The role of surfactants on ethylcellulose oleogel structure and mechanical properties. Carbohyd Polym. 2015;127:355–362. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.03.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidovich-pinhas M, Barbut S, Marangoni AG. Development, characterization, and utilization of food-grade polymer oleogels. Ann Rev Food Sci Technol. 2016;7(1):65–91. doi: 10.1146/annurev-food041715-033225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidovich-Pinhas M. Oil structuring using polysaccharides. Curr Opin Food Sci. 2019;27:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cofs.2019.04.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Souza RJ, Mente A, Maroleanu A, Cozma AI, Ha V, et al. Intake of saturated and trans unsaturated fatty acids and risk of all cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes: systematic review and meta analysis of observational studies. BMJ. 2015;351:h3978. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h3978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demirkesen I, Mert B. Utilization of beeswax oleogel-shortening mixtures in gluten-free bakery products. JAOCS, J Am Oil Chem Soc. 2019;96(5):545–554. doi: 10.1002/aocs.12195. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doan CD, Van De Walle D, Dewettinck K, Patel AR. Evaluating the oil-gelling properties of natural waxes in rice bran oil: rheological, thermal, and microstructural study. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 2015;92(6):801–811. doi: 10.1007/s11746-015-2645-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doan CD, Tavernier I, Sintang MDB, Danthine S, Van de Walle D, Rimaux T, Dewettinck K. Crystallization and gelation behavior of low- and high melting waxes in rice bran oil: a case-study on berry wax and sunflower wax. Food Biophys. 2017;12(1):97–108. doi: 10.1007/s11483-016-9467-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fayaz G, Goli SAH, Kadivar M, Valoppi F, Barba L, Calligaris S, Nicoli MC. Potential application of pomegranate seed oil oleogels based on monoglycerides, beeswax and propolis wax as partial substitutes of palm oil in functional chocolate spread. LWT. 2017;86:523–529. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2017.08.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fayaz G, Calligaris S, Nicoli MC. Comparative study on the ability of different oleogelators to structure sunflower oil. Food Biophys. 2020;15(1):42–49. doi: 10.1007/s11483-019-09597-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Flöter E, Wettlaufer T, Conty V, Scharfe M. Oleogels—their applicability and methods of characterization. Molecules. 2021;26(6):1673. doi: 10.3390/molecules26061673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco D, Martins AJ, López-Pedrouso M, Cerqueira MA, Purriños L, Pastrana LM, António AA, Carlos Z, Lorenzo JM. Evaluation of linseed oil oleogels to partially replace pork backfat in fermented sausages. J Sci Food Agric. 2020;100(1):218–224. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.10025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitas CAS, de Sousa PHM, Soares DJ, da Silva JYG, Benjamin SR, Guedes MIF. Carnauba wax uses in food—a review. Food Chem. 2019;291:38–48. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.03.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Estaca J, Herrero AM, Herranz B, Álvarez MD, Jiménez-Colmenero F, Cofrades S. Characterization of ethyl cellulose and beeswax oleogels andtheir suitability as fat replacers in healthier lipid pâtés development. FoodHydrocolloids. 2019;87:960–969. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2018.09.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gur SO, Zbikowska A, Przybysz M, Kowalska M. Assessment of physical properties of structured oils and palm fat. Mater Plast. 2017;54(4):800–805. doi: 10.37358/mp.17.4.4949. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang HS, Kim S, Singh M, Winkler-Moser JK, Liu SX. Organogel formation of soybean oil with waxes. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 2012;89(4):639–647. doi: 10.1007/s11746-011-1953-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang HS, Singh M, Bakota EL, Winkler-Moser JK, Kim S, Liu SX. Margarine from organogels of plant wax and soybean oil. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 2013;90:1705–1712. doi: 10.1007/s11746-013-2315-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang HS, Fhaner M, Winkler-Moser JK, Liu SX. Oxidation of fish oil oleogels formed by natural waxes in comparison with bulk oil. Euro J Lipid Sci Technol. 2018;120(5):1700378. doi: 10.1002/ejlt.201700378. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jang A, Bae W, Hwang H, Gyu H, Lee S. Evaluation of canola oil oleogels with candelilla wax as an alternative to shortening in baked goods. Food Chem. 2015;187:525–529. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.04.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung D, Oh I, Lee J, Lee S. Utilization of butter and oleogel blends in sweet pan bread for saturated fat reduction: dough rheology and baking performance. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2020;125:109194. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2020.109194. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kanya TCS, Rao LJ, Sastry MCS. Characterization of wax esters, free fatty alcohols and free fatty acids of crude wax from sunflower seed oil refineries. Food Chem. 2007;101(4):1552–1557. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.04.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Liu G. Corn oil-based oleogels with different gelation mechanisms as novel cocoa butter alternatives in dark chocolate. J Food Eng. 2019;263:114–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2019.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Guo R, Wang M, Bi Y, Zhang H, Xu X. Development and characterization of compound oleogels based on monoglycerides and edible waxes. ACS Food Sci Technol. 2022;2(2):302–314. doi: 10.1021/acsfoodscitech.1c00390. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lim J, Hwang HS, Lee S. Oil-structuring characterization of natural waxes in canola oil oleogels: rheological, thermal, and oxidative properties. Appl Biol Chem. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s13765-016-0243-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lim J, Jeong S, Oh IK, Lee S. Evaluation of soybean oil-carnauba wax oleogels as an alternative to high saturated fat frying media for instant fried noodles. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2017;84:788–794. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2017.06.054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Madureira AR, Campos DA, Fonte P, Nunes S, Reis F, Gomes AM, Sarmento B, Pintado MM. Characterization of solid lipid nanoparticles produced with carnauba wax for rosmarinic acid oral delivery. RSC Adv. 2015;5(29):22665–22673. doi: 10.1039/C4RA15802D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manzoor S, Masoodi FA, Naqash F, Rashid R. Oleogels: promising alternatives to solid fats for food applications. Food Hydrocoll Health. 2022;2:100058. doi: 10.1016/j.fhfh.2022.100058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martins AJ, Cerqueira MA, Cunha R, Vicente AA. Fortified beeswax oleogels: effect of β-carotene on the gel structure and oxidative stability. Food Function. 2017;8:4241–4250. doi: 10.1039/C7FO00953D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins AJ, Vicente AA, Pastrana LM, Cerqueira MA. Oleogels for development of health-promoting food products. Food Sci Human Wellness. 2020;9:31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.fshw.2019.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mert B, Demirkesen I. Evaluation of highly unsaturated oleogels as shortening replacer in a short dough product. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2016;68:477–484. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2015.12.063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mert B, Demirkesen I. Reducing saturated fat with oleogel/shortening blends in a baked product. Food Chem. 2016;199(December):809–816. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.12.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Öǧütcü M, Yilmaz E. Characterization of hazelnut oil oleogels prepared with sunflower and carnauba waxes. Int J Food Prop. 2015;18(8):1741–1755. doi: 10.1080/10942912.2014.933352. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oh I, Amoah C, Lim J, Jeong S, Lee S. Assessing the effectiveness of wax-based sunflower oil oleogels in cakes as a shortening replacer. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2017;86:430–437. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2017.08.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oh I, Lee JH, Lee HG, Lee S. Feasibility of hydroxypropyl methylcellulose oleogel as an animal fat replacer for meat patties. Food Res Int. 2019;122:566–572. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2019.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandolsook S, Kupongsak S. Influence of bleached rice bran wax on the physicochemical properties of organogels and water-in-oil emulsions. J Food Eng. 2017;214:182–192. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2017.06.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park C, Maleky F. A critical review of the last 10 years of oleogels in food. Front Sustain Food Syst. 2020;4:139. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2020.00139. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park C, Bemer HL, Maleky F. Oxidative stability of rice bran wax oleogels and an oleogel cream cheese product. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 2018;95(10):1267–1275. doi: 10.1002/aocs.12095. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patel AR. Oil structuring: concepts, overview and future perspectives. In: Patel AR, editor. Edible oil structuring: concepts: methods and Applications. Cambridge: Royal Society of Chemistry; 2017. pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Patel AR, Dewettinck K. Edible oil structuring: an overview and recentupdates. Food Funct. 2016;7(1):20–29. doi: 10.1039/c5fo01006c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel AR, Cludts N, Sintang MDB, Lesaffer A, Dewettinck K. Edible oleogels based on water soluble food polymers: Preparation, characterization and potential application. Food Funct. 2014 doi: 10.1039/c4fo00624k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel AR, Babaahmadi M, Lesaffe A, Dewettinck K. Rheological profiling of organogels prepared at critical gelling concentrations of natural waxes in a triacylglycerol solvent. J Agric Food Chem. 2015;63(19):4862–4869. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b01548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pehlivanoğlu H, Demirci M, Toker OS, Konar N, Karasu S, Sagdic O. Oleogels, a promising structured oil for decreasing saturated fatty acid concentrations: production and food-based applications. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2018;58(8):1330–1341. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2016.1256866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puscas A, Muresan V, Socaciu C, Muste S. Oleogels in food: a review of current and potential applications. Foods. 2020;9(1):1–27. doi: 10.3390/foods9010070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha JCB, Lopes JD, Mascarenhas MCN, Arellano DB, Guerreiro LMR, da Cunha RL. Thermal and rheological properties of organogels formed by sugarcane or candelilla wax in soybean oil. Food Res Int. 2013;50(1):318–323. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2012.10.043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Soleimanian Y, Goli SAH, Shirvani A, Elmizadeh A, Marangoni AG. Wax-based delivery systems: preparation, characterization, and food applications. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2020 doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanasescu M, Cho E, Manson JE, Hu FB. Dietary fat and cholesterol and the risk of cardiovascular disease among women with type 2 diabetes. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79(6):999–1005. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.6.999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavernier I, Doan CD, Van De Walle D, Danthine S, Rimaux T, Dewettinck K. Sequential crystallization of high and low melting waxes to improve oil structuring in wax-based oleogels. RSC Adv. 2017;7(20):12113–12125. doi: 10.1039/c6ra27650d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thakur D, Singh A, Prabhakar PK, Meghwal M, Upadhyay A. Optimization and characterization of soybean oil-carnauba wax oleogel. LWT. 2022;157:113108. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2022.113108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Toro-Vazquez JF, Morales-Rueda JA, Dibildox-Alvarado E, Charó-Alonso M, Alonzo-Macias M, González-Chávez MM. Thermal and textural properties of organogels developed by candelilla wax in safflower oil. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 2007;84(11):989–1000. doi: 10.1007/s11746-007-1139-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Toro-Vazquez JF, Mauricio-Pérez R, González-Chávez MM, Sanchez-Becerril M, Ornelas-Paz JJ, Perez-Martinez JD. Physical properties of organogels and water in oil emulsions structured by mixtures of candelilla wax and monoglycerides. Food Res Int. 2013;54(2):1360–1368. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2013.09.046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vali SR, Ju YH, Kaimal TNB, Chern YT. A process for the preparation of food-grade rice bran wax and the determination of its composition. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 2005;82(1):57–64. doi: 10.1007/s11746-005-1043-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Ando S, Ishida Y, Ohtani H, Tsuge S, Nakayama T. Quantitative and discriminative analysis of carnauba waxes by reactive pyrolysis-GC in the presence of organic alkali using a vertical microfurnace pyrolyzer. J Anal Appl Pyrol. 2001;58–59:525–537. doi: 10.1016/S0165-2370(00)00155-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wijarnprecha K, Aryusuk K, Santiwattana P, Sonwai S, Rousseau D. Structure and rheology of oleogels made from rice bran wax and rice bran oil. Food Res Int. 2018;112:199–208. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2018.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler-Moser JK, Anderson J, Felker FC, Hwang HS. Physical properties of beeswax, sunflower wax, and candelilla wax mixtures and oleogels. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 2019;96(10):1125–1142. doi: 10.1002/aocs.12280. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yi B, Kim MJ, Lee SY, Lee J. Physicochemical properties and oxidative stability of oleogels made of carnauba wax with canola oil or beeswax with grapeseed oil. Food Sci Biotechnol. 2017;26(1):79–87. doi: 10.1007/s10068-017-0011-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yılmaz E, Öğütçü M, Yüceer YK. Physical Properties, volatiles compositions and sensory descriptions of the aromatized hazelnut oil-wax organogels. J Food Sci. 2015;80:S2035–S2044. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.12992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao M, Lan Y, Cui L, Monono E, Rao J, Chen B. Formation, characterization, and potential food application of rice bran wax oleogels: expeller pressed corn germ oil versus refined corn oil. Food Chem. 2020;309:125704. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.125704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.