Abstract

Konjac gel (KG) food is a popular choice among consumers due to its delicious taste, low-calorie content, and ability to provide satiety. The aim of the study was to evaluate the effects of the addition of mung bean starch (MBS), corn starch (CS), and sweet potato starch (SPS) on the water solubility, gel strength, microstructure, and viscosity of KG. The experimental results showed that MBS exhibited the largest amylose content (47.07 ± 1.71%), and SPS had the lowest amylose content (27.92 ± 1.24%). With the increase of starch concentration, the gel strength and viscosity of KG increased, the KG with 3% MBS had higher water solubility and stronger gel strength, and the KG with 3% SPS had better viscosity. In addition, according to the scanning electron microscope, the microstructure of KG without starch was a porous honeycomb, and the network structure of CS/KG was more orderly and uniform. The microstructure of MBS/KG was tightly wrinkled, while the honeycomb structure of SPS/KG was more orderly and the network outline was clearer. The addition of starch could improve the quality of KG, the type of starch used had different effects.

Keywords: Konjac gel, Starch, Gel strength, Microstructure, Viscosity

Introduction

Konjac flour (KF) is derived from the tubers of Konjac plants using various industrial techniques and primarily consists of Konjac glucomannan (KGM) (Tatirat Charoenrein 2011). KGM is a non-ionic hydrocolloid dietary fiber that is soluble in water. It is high in dietary fiber, low in protein and vitamins, and can expand, which promotes satiety and reduces fat intake. Additionally, KGM has been found to have a weight loss function (Devaraj et al. 2019; Li et al. 2021). KGM has been found to have rich nutritional value and unique healthcare functions. Its pharmacological effects have also been shown to be prominent, with the ability to lower blood pressure, blood lipid, and blood glucose levels (Chen et al. 2019). but alsodispersing toxins, promoting blood circulation, and promoting defecation (Zhang Li 2021), and appetizers have certain effects. In recent years, the popularity of gel food has increased with the development of society. Among the various gel foods, konjac gel food stands out due to its unique taste, low-calorie count, and strong satiety. As a result, it has become more favored by people.

To enhance the quality and performance of konjac gel food, KGM is often combined with other substances as it has poor structure, a heavy alkali flavor, and dehydration shrinkage. (Li et al. 2014). KGM is reported to interact synergistically with starches of various botanic origins: maize (Khanna Tester 2006), mung bean (Lin et al. 2021), pea (Sun et al. 2020), and rice (Charoenrein et al. 2011). Starch, composed mainly of amylose and amylopectin, is a crucial and abundant food hydrocolloid. The proportion of these components has a significant impact on konjac gel. Maize starch, with its moderate particle size and low price, possesses desirable characteristics such as gelatinization, rheology, and water retention that can enhance the rheological properties of protein gels. Additionally, it can serve as an excipient or filler during processing (Yu et al. 2020). Mung beans have a high amylose content (Li et al. 2010), resulting in good gel formation and desirable color, taste, and water-holding capacity of gel products, making them a popular choice among consumers. On the other hand, sweet potato starch is characterized by its high amylopectin content, strong swelling power, transparency, and viscosity. Despite extensive research on the effect of KGM addition on starch gel, there is limited information available on the effect of starch on konjac gel.

Thus, in summary, the aim of this study was to investigate the effect of the addition of MBS, CS, and SPS on the gel properties of konjac. The findings of this study can serve as a theoretical foundation for the creation of new types of gel foods.

Materials and methods

Materials

Food-grade SPS and MBS were purchased from Xinxiang Liangrun Whole Grain Food Co., Ltd. (Henan, China). CS was obtained from Nanjing Ganjuyuan Sugar Industry Co., Ltd. (Nanjing, China). KF was purchased from Yichang Weite Konjac Glue Co., Ltd. (Hubei, China).

Determination of amylose content in starch

After the sample was sieved through an 80-mesh sieve, 0.1000 g of the sample to be tested was weighed and placed in a 100 mL volumetric flask, 1 mL of anhydrous ethanol was added to fully wet the sample, and 9 mL of 1 mol / L NaOH solution was added. Disperse in boiling water for 10 min, quickly cool down and add water to volume 100 mL. 5 mL of sample solution (5 mL of 0.09 mol / L NaOH solution was taken as blank control) was put into a 100 mL volumetric flask. Add 50 ml distilled water, l mL mol / L HAC solution, l mL iodine reagent, and diluted to 100 mL with distilled water for 10 min. After the color development was completed, the blank control solution was used for calibration, and then the amylose content of the sample was determined by DPCZ-III (Zhejiang Topyun Agricultural Technology Co., Ltd.) amylose analyzer.

Preparation of mixed konjac gel

The starch content of SBS/KG mixtures was shown in Table 1, and mixtures were prepared as follows. CS, MBS, or SPS powder was added to the deionized water containing edible soda (8%, w / v) at 80 °C, and continuously stirred for 5 min to prepare CS, MBS, or SPS solution. The konjac powder (5%, w / v) was added to CS, MBS, or SPS solution and continuously stirred to obtain the mixture. After standing at room temperature for 1.5 h, it was boiled at 100 °C and cooled to room temperature. After freezing at − 20 °C for 1.5 h and thawing at room temperature for 2 h, the surface was soaked in citric acid solution (0.50%, w / v) for 1 h, and then cleaned with deionized water twice. All mixtures prepared for the following determination were stored at room temperature.

Table 1.

Test grouping situation

| Number | CS (%) | Number | MBS (%) | Number | SPS (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y0 | 5.00 | L0 | 5.00 | H0 | 5.00 |

| KY2 | 2.00 | KL2 | 2.00 | KH1 | 1.00 |

| KY3 | 3.00 | KL3 | 3.00 | KH2 | 2.00 |

| KY4 | 4.00 | KL4 | 4.00 | KH3 | 3.00 |

Determination of water solubility index (WSI)

According to the method of Jiang et al. (Jiang et al. 2019) with some modifications. Each sample and distilled water were mixed in a 50 mL centrifuge tube to prepare a 0.50% sample suspension. Subsequently, the sample suspensions were heated in a water bath at 95 °C for 30 min and stirred for 5 min. After cooling to room temperature, samples were centrifuged at 5000 g for 10 min at four °C. The supernatant was transferred to the culture dish and dried at 105 °C until the constant weight. The sediment mass at the bottom of the centrifuge tube. WSI was calculated using the following formulas:

| 1 |

where:m0 = Mass of sample.

m1 = Drying constant weight mass of supernatant.

Determination of gel strength

The gel strength of each compound gel was measured using the method of wang et al. (Wang et al. 2020) with some modifications. The samples were cut into a cube with a side length of 1 cm, and the gel strength of composite gels was obtained using a TA-XT Plus physical property analyzer (Stable Micro Systems company, UK). The main parameters were set as follows: the cylindrical probe was P0.5 (5 mm), the trigger force was 5.00 g, the decline rate before the measurement was 2.00 mm / s, the test speed was 1.00 mm / s, the ascending speed was 1.00 mm / s, and the compression depth was 4.00 mm.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

The morphological properties of the gel were studied by using a VEGA3SBU scanning electron (Czech Tesan Corporation). The sample was placed on the SEM stub and sprayed with gold for 10.00 min. An accelerated potential of 15 kV was used during 200 × and 500 × microphotography (Gul et al. 2014).

Pasting properties

7% (the percentage of konjac powder) of alkali water and different mass of starch was mixed evenly, taking 10 mL mixture in an aluminum crucible, added 0.5 g konjac powder, and aluminum crucible quickly stuck into the rotary rheometer (Guangzhou Laimei Technology Co., Ltd.) in the rotating tower, pressed the cap to start the measurement.

The main parameters were set as follows: heating to 50 °C within 1 min, balancing at 50 °C for 1 min, then heating to 80 °C at a rate of 15 °C / min, holding at 80 °C for 13 min, and then cooling to 50 °C at the same rate for 25 min.

Statistical analysis

All measurements were done in triplicate, and the results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. All charts were plotted by Origin 2018. Duncan's multi-range test (P < 0.05) was performed to the mean separation and one-way analysis of variance ANOVA. SPSS 23.0 was used for statistical analysis.

Results and discussion

Analysis of amylose content in starch

The order of amylose content from large to small was MBS > CS > SPS, which were 47.07 ± 1.71%, 30.21 ± 1.25%, and 27.92 ± 1.24%, respectively, showing significant differences (p < 0.05), which was consistent with Wang Lin (2021) found that the amylose content of legume starch was the highest and the amylose content of potato starch was the lowest (Table 2).

Table 2.

Amylose content in starch

| Item | CS | SPS | MBS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amylose content (Dry basis),% | 30.21 ± 1.25b | 27.92 ± 1.24c | 47.07 ± 1.71a |

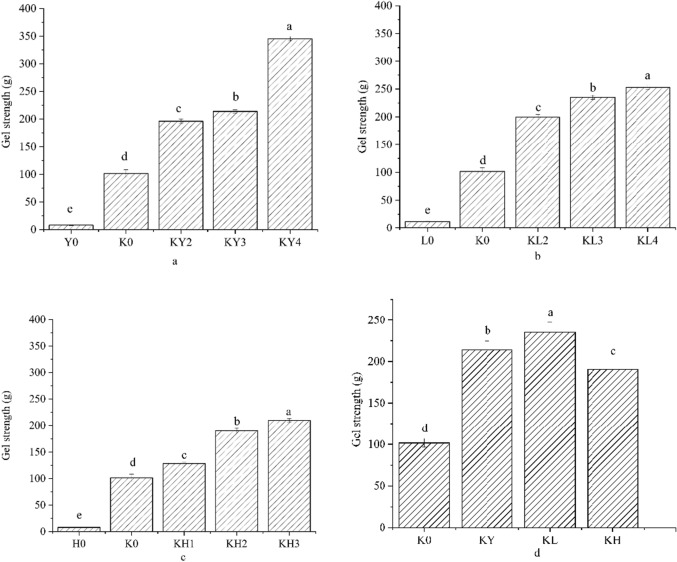

Water solubility index of compound gel

The water solubility index (WSI) was measured for both starch gels and KGs at 95 °C, as shown in Fig. 1. The results indicated a significantly higher WSI for KGs compared to starch gels, with varying WSI values observed among different starch gels. Furthermore, the addition of exogenous starch led to a significant increase in the WSI of KG.

Fig. 1.

Water solubility index of different gel systems. Note: Y0 is pure corn starch gel; L0 is pure mung bean starch gel; H0 is pure sweet potato starch gel; K0 is pure konjac starch gel; KY is 3% corn starch konjac gel; KL is 3% mung bean starch konjac gel; KH is 3% sweet potato starch konjac gel. All data are expressed as mean ± standard deviations (n = 3). According to Duncan's multiple range test (P < 0.05), different letters are significantly different

The water-holding capacity of KGM was found to be higher than that of starches due to the presence of more hydroxyl groups in the KGM backbone and its good water solubility (Gläser et al. 2004). Moreover, the ratio of amylose to amylopectin within the starch molecule affects its ability to bind water, resulting in varying WSI of different starches (Charoenrein et al. 2011). The addition of exogenous starch resulted in a significant increase in the WSI of KGs. KL showed the highest increase (66.86 ± 1.40%), followed by KY (54.61 ± 1.15%) and KH (53.55 ± 0.22%), with increases of 29.36%, 17.11%, and 16.05% compared to K0 (37.50 ± 3.54%), respectively. This increase in WSI was attributed to the amylose content in starch(Bhat Riar 2016), with MBS having the highest amylose content among the three starches tested. As a result, WSI increased significantly after adding KGs.

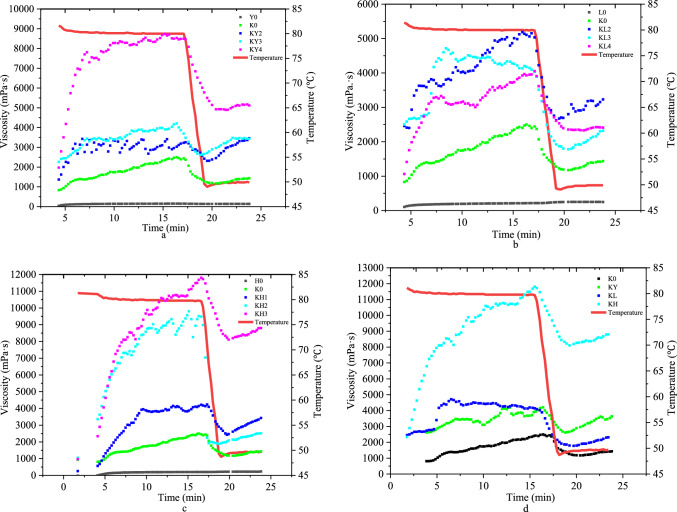

Gel strength analysis

The gel strength of starch gels and KGs was determined, and the results are presented in Fig. 1. It was observed that the gel strength of starch gels (Y0, L0, H0) was significantly lower than that of KGs (K0, KY, KL, KH). This could be attributed to the removal of acetyl groups on the KGM molecular chain during alkaline heating. As a result, KGM became a disordered bare chain, leading to improved intramolecular and intermolecular hydrogen bond interactions, and a significant increase in gel strength(Charoenrein et al. 2011). The addition of different starches significantly increased the gel strength of KY, KL, and KH (p < 0.05), indicating that the introduction of starch increased the gel strength of KG and improved the characteristics and quality of KGs to a certain extent. As the starch content increased, the concentration of the mixed system also increased. This led to an increase in the interaction probability between KGM and CS, MBS and SPS. As a result, the interaction distance between molecules decreased and the number of hydrogen bonds formed between molecules increased. These changes resulted in a more compact and stable three-dimensional network structure of the gel, leading to an increase in gel strength (Connolly et al. 2010).

Figure 2 d demonstrates the impact of various starches on KGs. The gel strength of MBS/KG was notably higher than that of CS and SPS when the additional amount of CS, MBS, and SPS was identical (p < 0.05). This could be attributed to the high amylose content of mung bean starch. There is a positive correlation between amylose content in starch and gel strength, as starch with high amylose content forms a dense network structure that is difficult to gel and significantly increases gel strength. This is consistent with the WSI experimental results.

Fig. 2.

Gel strength of different konjac bionic tripe. a The gel strength of different corn starch addition, b The Gel strength of different mung bean starch addition, c The Gel strength of different sweet potato starch addition, d The gel strength of 3% different starch. Note: Y0 is pure corn starch gel; K0 is pure konjac starch gel; KY2 is 2% corn starch konjac gel; KY3 is 3% corn starch konjac gel; KY4 is 4% corn starch konjac gel; L0 is pure mung bean starch gel; KL2 is 2% mung bean starch konjac gel; KL3 is 3% mung bean starch konjac gel; KL4 is 4% mung bean starch konjac gel; H0 is pure sweet potato starch gel; KH1 is 1% sweet potato starch konjac gel; KH3 is 2% sweet potato starch konjac gel; KH3 is 3% sweet potato starch konjac gel; KY is 3% corn starch konjac gel; KL is 3% mung bean starch konjac gel; KH is 3% sweet potato starch konjac gel. All data are expressed as mean ± standard deviations (n = 3). According to Duncan's multiple range test (P < 0.05), different letters are significantly different

Scanning electron microscope (SEM)

In order to elucidate the effect of different starches on the microstructure of KG, the micrographs of KG were observed by SEM. Figure 3 displays the microstructure of both SGs and KGs at magnifications of 200 × and 500x. As illustrated in Fig. 3, the microstructure of the various gels exhibited porosity after freeze-drying; however, the pore size, number, and arrangement varied. Different types of starch gel exhibited a porous sponge structure, and a similar microstructure has also been observed in the study of Han Hamaker (Han Hamaker 2000) and Li et al. (Li et al. 2004). The microstructure of K0 was a porous honeycomb, which could maintain a certain elasticity of the gel (Wang et al. 2020). However, the pore size distribution was uneven and the pores were connected in sheets, forming a three-dimensional network structure similar to the findings of Huang's research. (Huang et al. 2021). The microstructure of Y0 was dense, but the wall was thick, the network structure was clear, and the holes were uniform, which might be caused by the heterogeneous gel formed by the interaction of starch and water molecules (Wang et al. 2013). The microstructure of H0 exhibited a chaotic pattern with a limited number of lamellae. On the other hand, the microstructure of L0 displayed a shallow lamellar structure, and the wall layer at the junction of each sheet was thin but contained many folds.

Fig. 3.

The SEM images of different starch konjac gels. A 200x, b 500x. Note: Y0 is pure corn starch gel; L0 is pure mung bean starch gel; H0 is pure sweet potato starch gel; K0 is pure konjac starch gel; KY is mung bean starch konjac gel; KL is mung bean starch konjac gel; KH is sweet potato starch konjac gel

It can be seen from Fig. 3 b that after the addition of starch, the microstructure of KGs and KG without starch were significantly different, which was because the interaction between starch and KGM led to an increase in the number of intertwined joints of KGs. The inclusion of CS in KG resulted in a more organized network structure and a more uniform pore size when compared to pure konjac gel. This effect can be attributed to the high concentration of molecular chain crowding. The introduction of MBS caused a significant change in the internal structure of KL, resulting in a compact and wrinkled shape. This suggests that MBS may have been filled into KG molecules with a lamellar structure, altering the structure and subsequent gel properties of the Konjac polysaccharide gel system (Ma et al. 2019). The microstructure of the compound H0 and K0 was significantly altered due to their relatively loose and chaotic network structure. Upon adding SPS to the compound, the microstructure displayed an orderly honeycomb structure with larger pores and a clearer network profile, as compared to PKG. Sun, et al. (Sun et al. 2020) found that the microstructure of the gel was related to the rheological properties, and the larger the G', the tighter the network structure in the SEM image. Han, & Hamaker (Han Hamaker 2000) also found that gels with dense, fibrous structures had lower viscosity than gels with honeycomb structures. The CS/KG had a more organized honeycomb shape compared to other starch gels. This difference could be attributed to the varying amylose and amylopectin content and molecular structure.

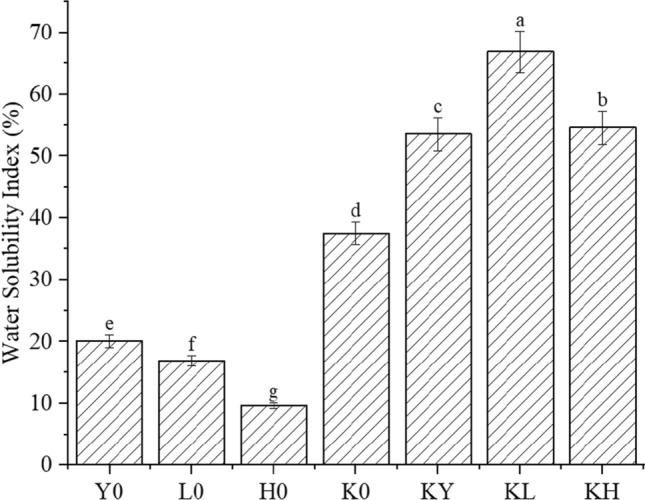

Pasting properties

A rotational rheometer was used to measure the viscosity change of starch and konjac with temperature and time to observe their behavior during mixing. The results in Fig. 4 demonstrate that the introduction of starch significantly increased the viscosity of KG at 80 °C (p < 0.05). The viscosity continued to increase with stirring time until it reached a certain value, after which it began to fluctuate. The high viscosity characteristics of konjac powder can be attributed to its large content of KGM. During the stirring process, konjac powder rapidly absorbs water, and some of it may exist in the form of a package. However, when the viscosity reaches a certain level, the konjac starch granules may rupture or disintegrate, leading to a decrease in viscosity. During the stirring process, the membrane surrounding the konjac flour was destroyed, causing the release of the flour. The flour mixed with an excessive amount of alkali water starch, leading to a decrease in the viscosity of the mixture. As stirring continued, the viscosity increased until it reached its peak. At this point, the konjac starch granules began to weaken, break, and disintegrate, causing a subsequent decrease in viscosity. During the cooling stage, the viscosity of the solution increases once again. This is caused by the amylose molecules exuded earlier becoming entangled or aggregated, resulting in the formation of a three-dimensional structure.

Fig. 4.

The viscosity curve of different starch konjac gel. a The viscosity curve of different corn starch addition, b The viscosity curve of different mung bean starch addition, c The viscosity curve of different sweet potato starch addition. d The viscosity curve of 3% different starch. Note: Y0 is pure corn starch gel; K0 is pure konjac starch gel; KY2 is 2% corn starch konjac gel; KY3 is 3% corn starch konjac gel; KY4 is 4% corn starch konjac gel; L0 is pure mung bean starch gel; KL2 is 2% mung bean starch konjac gel; KL3 is 3% mung bean starch konjac gel; KL4 is 4% mung bean starch konjac gel; H0 is pure sweet potato starch gel; KH1 is 1% sweet potato starch konjac gel; KH3 is 2% sweet potato starch konjac gel; KH3 is 3% sweet potato starch konjac gel

Figure 4 d shows the effect of different starches at the same concentration on KG viscosity. As shown in Fig. 4 d, the viscosity of SPS / KG was significantly higher than that of CS and MBS (p < 0.05). Studies have shown that there is a negative correlation between viscosity and amylose content (Lindeboom et al. 2005), Among the three starches, SPS has the lowest amylose content. After adding KG, its viscosity increased significantly (p < 0.05). Sun, et al. (Sun et al. 2020) showed that the viscosity of starch gel with KGM added was higher than that of starch gel without KGM added. This result may be due to the cross-linking between KGM, the leached amylose, and amylopectin.

Ma et al. (Ma et al. 2019) also found that the viscosity of CS/KGM mixtures increased with the concentration of KGM.

It is worth noting that the viscosity of other mixed systems increases with the increase of starch concentration, while the viscosity of the MBS / KG mixed system decreases with the increase of starch concentration, which may be caused by the unique structure in MBS. The specific reason needs further exploration.

Conclusion

The KG added with CS, MBS, and SPS was prepared, and its gel properties were characterized. Our results showed that the addition of starch resulted in stronger water solubility, gel strength, and viscosity compared to KG without starch addition. Our results showed that the gel strength and viscosity of KG increased with the increase in starch concentration. The MBS had the highest amylose content (47.07 ± 1.71%), and the KG prepared by MBS had higher water solubility and gel strength. The KG prepared by SPS with the lowest amylose content (27.92 ± 1.24%) had better viscosity. In addition, according to SEM, compared with the KG without starch, the network structure of CS/KG was more orderly and uniform, the microstructure of MBS /KG was closely wrinkled, and the honeycomb structure of SPS/KG was more orderly and the network profile was clearer. The results showed that the addition of starch could improve the quality of KG.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: [LW; XZ; LZ]; Data curation: [LZ; LW; YH]; Formal analysis: [LW; XX; LZ]; Funding acquisition: [XZ; LL; SS]; Investigation: [YH; XZ; LZ]; Project administration: [LL; XZ; SS]; Resources: [YH; LZ; LW; SS]; Supervision: [LL; LW; YH; SS]; Visualization: [LZ; LW]; Writing-original draft: [LZ; LL]; Writing-review&editing: [LZ; LW].

Funding

This work was supported by the Sichuan Science and Technology Program Fund (2022NSFSC1741).

Data availability

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

There are no competes of interest to declare.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Li Li and Li Zhang have contributed to the work equally and should be regarded as co-first authors.

Contributor Information

Li Li, Email: kokonice@139.com.

Li Zhang, Email: 321083202104@stu.suse.edu.cn.

Yang Han, Email: 1303711464@qq.com.

Lei Wen, Email: 1143679343@qq.com.

Shujuan Shao, Email: 315572303@qq.com.

Xuyan Zong, Email: zongxuyan@suse.edu.cn, Email: suse62651@139.com.

References

- Bhat FM, Riar CS. Effect of amylose, particle size & morphology on the functionality of starches of traditional rice cultivars. Int J Biol Macromol. 2016;92:637–644. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.07.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charoenrein S, Tatirat O, Rengsutthi K, Thongngam M. Effect of konjac glucomannan on syneresis, textural properties and the microstructure of frozen rice starch gels. Carbohyd Polym. 2011;83:291–296. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2010.07.056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Nie Q, Hu J, Huang X, Zhang K, Pan S, Nie S. Hypoglycemic and hypolipidemic effects of glucomannan extracted from Konjac on type 2 diabetic rats. J Agri Food Chem. 2019;67:5278–88. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.9b01192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly ML, Lovegrove JA, Tuohy KM. Konjac glucomannan hydrolysate beneficially modulates bacterial composition and activity within the faecal microbiota. J Funct Foods. 2010;2:219–224. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2010.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Devaraj RD, Reddy CK, Xu B. Health-promoting effects of konjac glucomannan and its practical applications: a critical review. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019;126:273–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.12.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gläser KR, Wenk C, Scheeder MRL. Evaluation of pork backfat firmness and lard consistency using several different physicochemical methods. J Sci Food Agri. 2004;84:853–862. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.1761. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gul K, Riar CS, Bala A, Sibian MS. Effect of ionic gums and dry heating on physicochemical, morphological, thermal and pasting properties of water chestnut starch. LWT - Food Sci Technol. 2014;59:348–355. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2014.04.060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Han XZ, Hamaker BR. Functional and microstructural aspects of soluble corn starch in pastes and gels. Starch/Stärke. 2000;52(2–3):76–80. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-379X(200004)52:2/3<76::AID-STAR76>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Q, Liu Z, Pei Y, Li J, Li B. Gelation behaviors of the konjac gum from different origins: A.guripingensis and A.rivirei. Food Hydrocoll. 2021;111:106152. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2020.106152. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Reddy CK, Huang K, Chen L, Xu B. Hydrocolloidal properties of flaxseed gum/konjac glucomannan compound gel. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019;133:1156–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.04.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna S, Tester R. Influence of purified konjac glucomannan on the gelatinisation and retrogradation properties of maize and potato starches. Food Hydrocoll. 2006;20:567–576. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2005.05.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li JH, Vasanthan T, Hoover R, Rossnagel BG. Starch from hull-less barley: IV. Morphological and structural changes in waxy, normal and high-amylose starch granules during heating. Food Res Int. 2004;37:417–428. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2003.09.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Shu C, Zhang P, Shen Q. Properties of starch separated from ten mung bean varieties and seeds processing characteristics. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2010;4:814–821. doi: 10.1007/s11947-010-0421-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Ye T, Wu X, Chen J, Wang S, Lin L, Li B. Preparation and characterization of heterogeneous deacetylated konjac glucomannan. Food Hydrocoll. 2014;40:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2014.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Shang L, Wu D, Dun H, Wei X, Zhu J, Zongo AWS, Li B, Geng F. Sodium caseinate reduces the swelling of konjac flour: a further examination. Food Hydrocoll. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2021.106923. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin S, Liu X, Cao Y, Liu S, Deng D, Zhang J, Huang G. Effects of xanthan and konjac gums on pasting, rheology, microstructure, crystallinity and in vitro digestibility of mung bean resistant starch. Food Chem. 2021;339:128001. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.128001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindeboom N, Chang P, Tyler R, Chibbar R. Granule-bound starch synthase I (GBSSI) in quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) and its relationship to amylose content. Cereal Chem. 2005;82:246–250. doi: 10.1094/CC-82-0246. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma S, Zhu P, Wang M. Effects of konjac glucomannan on pasting and rheological properties of corn starch. Food Hydrocoll. 2019;89:234–240. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2018.10.045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Wang M, Ma S, Wang H. Physicochemical characterization of rice, potato, and pea starches, each with different crystalline pattern, when incorporated with Konjac glucomannan. Food Hydrocoll. 2020;101:405499. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2019.105499. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tatirat O, Charoenrein S. Physicochemical properties of konjac glucomannan extracted from konjac flour by a simple centrifugation process. LWT - Food Sci Technol. 2011;44:2059–2063. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2011.07.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Xie B, Xiong G, Wu W, Wang J, Qiao Y, Liao L. The effect of freeze–thaw cycles on microstructure and physicochemical properties of four starch gels. Food Hydrocoll. 2013;31:61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2012.10.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Xia M, Zhou Y, Wang X, Ma J, Xiong G, Wang L, Wang S, Sun W. Gel properties of grass carp myofibrillar protein modified by low-frequency magnetic field during two-stage water bath heating. Food Hydrocoll. 2020;107:105920. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2020.105920. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu B, Zheng L, Cui B, Zhao H, Liu P. The effects of acetylated distarch phosphate from tapioca starch on rheological properties and microstructure of acid-induced casein gel. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;159:1132–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Li Y. Comparison of physicochemical and mechanical properties of edible films made from navy bean and corn starches. J Sci Food Agri. 2021;101:1538–1545. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.10772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Not applicable.