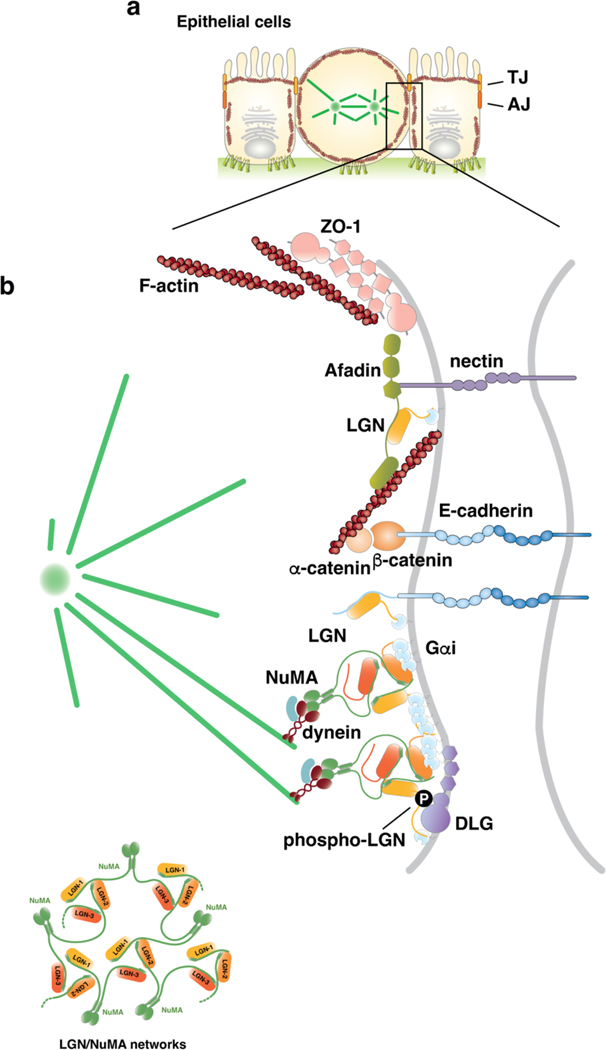

Figure 3. Molecular mechanisms of oriented planar cell divisions.

a) Schematic representation of epithelial mitosis in which the dividing cell rounds up maintaining adhesive junctions with neighbouring cells and with the extracellular matrix (ECM) at the basal site. Epithelial cell–cell contacts include adherens and tight junctions. b) Enlarged view of the molecular players accumulating at the lateral membrane during epithelial mitoses to promote planar cell divisions. Microtubule motors organized on dynein–dynactin–NuMA complexes are recruited laterally by Gαi–LGN–NuMA. Binding of NuMA to LGN and Gαi is compatible with the concomitant association of phospho (P)-LGN to the GK domain of the baso-lateral protein DLG because this LGN phosphorylation — mediated by the apical polarity kinase aPKC — occurs on the linker region between the Tetratrico-Peptide-Repeat (TPR) domain and the GoLoco motifs. In addition, the LGN-TPR interacts directly with the cytoplasmic tail of E-cadherin and with the actin-binding protein Afadin that localizes at the tight junctions with nectin [G] and ZO-1. Cell–cell junctions respond to mechanical forces by changing their organization and function (mechanosensing). Hence, forces acting tissue-wide, such as compression or stretching that can result from, for example, changes in cell number or morphogenetic movements, can be transmitted to regulate spindle orientation.