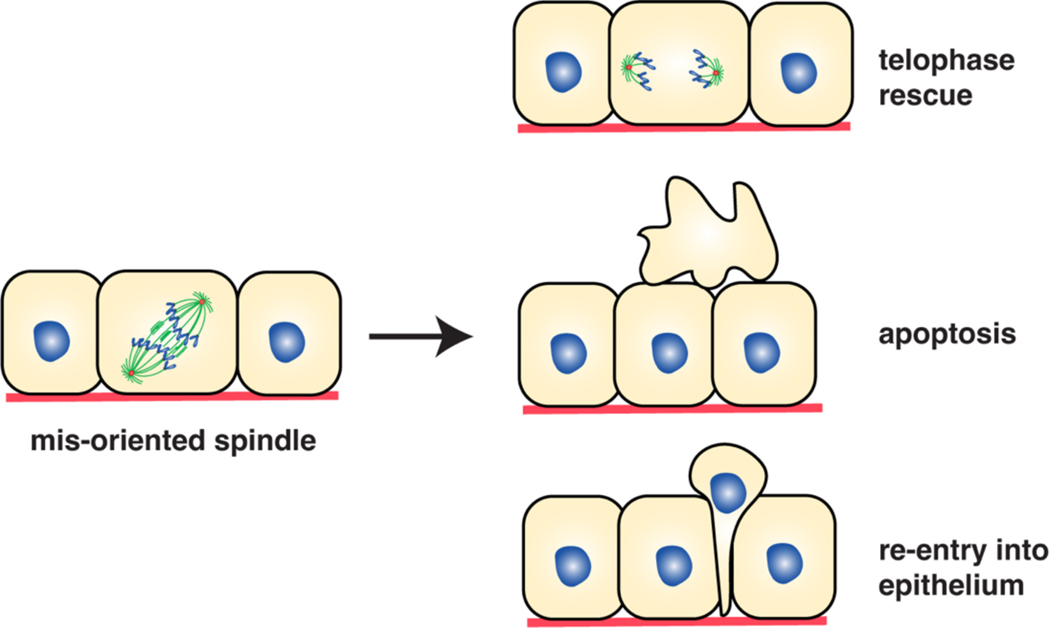

Figure 6. Tumorigenic consequences of spindle misalignment and tissue responses to ameliorate spindle misorientation.

a) Loss of spindle orientation in a tissue is generally not sufficient to confer tumorigenic potential, likely via the existence of various rescue mechanisms operating in the tissue (see part c). However, as shown in this example, loss of spindle orientation (for example, owing to mutations associated with spindle positioning machinery or changes in intracellular or extracellular cues (see Figure 5)), and specifically, asymmetric cell division of a progenitor cell in a simple epithelium, might collaborate with oncogenes to promote tumour formation. Note that the order of eventscould be reversed, with spindle positioning defects preceding oncogenic insults. b) In a stratified epithelium, the tissue can respond to some oncogenic mutations by increasing divisions perpendicular to the basement membrane. This generates differentiated daughters, limiting the potential effect of hyperproliferation, resulting from the loss of asymmetric divisions and increased generation of stem/progenitor cells. However, when oncogenic mutations co-exist with the loss of spindle orientation, this may lead to tumour growth. c) Tissues have multiple ways to deal with spindles that are misoriented in anaphase. They may correct these errors later in telophase, undergo apoptosis to eliminate the misplaced cell, or re-integrate the cell back into the epithelium.